Meckel's diverticulum is a normal anatomic variant found in 2% of the population. It is a remnant of the vitelline duct, which is usually located on the antimesenteric border of the ileum, within about 60 cm of the terminal ileum. As a congenital variant, Meckel's diverticula are often found in children and less commonly present in the adult population. The anatomic variant was initially identified by Fabricus Hildanus in 1598; however, Johann Meckel was the first to publish a detailed description of this not uncommon finding.1

From an embryological standpoint, a Meckel's diverticulum originates when the vitelline (or omphalomesenteric) duct, which normally connects the primitive gut to the yolk sac, fails to obliterate around the seventh or eighth week of gestation. This leads to several possible anomalies, including an omphalomesenteric fistula, an enterocyst, a fibrous band connecting the intestine to the umbilicus or a Meckel's diverticulum with or without a fibrous cord connecting to the umbilicus.2–4

Anatomically, the Meckel's diverticulum is a true diverticulum containing all layers of the small intestine, arising from the anti-mesenteric border of the ileum and receiving its blood supply from a remnant of the vitelline artery, which emanates from the superior mesenteric artery. A commonly quoted “rule of 2s” also applies: (1) 2% of the population have the anomaly, (2) it is approximately 2 inches in length, (3) it is usually found within 2 feet of the ileocecal valve, (4) it is often found in children under 2 years of age and (5) it affects males twice as often as females.2–6 Although these are good general guidelines, they are not based on accurate data. In an autopsy series, 0.14%–4.5% of cadavers contained a Meckel's diverticulum.7–11 The average length of a Meckel's diverticulum is 3 cm, with 90% ranging between 1 cm and 10 cm and the longest recorded being 100 cm.11–14 The mean distance from the ileocecal valve seems to vary with age, as Yamaguchi and colleagues14 showed in their study of 600 patients, with an average distance of 34 cm for children under 2 years of age. In people aged 3–21 years, the average distance of the Meckel's diverticulum from the ileocecal valve is 46 cm and for adults is 67 cm. The Meckel's diverticulum has actually been found to occur equally in both sexes,6,15–18 but it causes complications more frequently in males.11,15,19 A good, up-to-date review of the history, embryology, anatomy, complications and treatment of Meckel's diverticulum can be found at http://www.emedicine.com/med/topic2797.htm, by Kuwajerwala and colleagues.2

Here we provide an illustrative presentation, outlining the common complications of Meckel's diverticulum in adults. We saw 2 of these cases within a 2-week period and 2 additional cases in the preceding 3 years.

Case reports

Case 1: perforation from diverticulitis

A 41-year-old previously healthy man presented with fever, nausea, vomiting and periumbilical pain of 3 days duration. Examination of the abdomen revealed involuntary guarding of the suprapubic region. Biochemical laboratory tests showed a normal lipase and urinary analysis, with an elevated white blood cell count of 18.3 × 109/L. A CT scan of the abdomen (Fig. 1) showed a normal appendix and bladder and normal kidneys and ureters. Significant findings include a distal small bowel obstruction near the terminal ileum (target lesion) and free fluid in the pelvis.

FIG. 1. CT abdomen/pelvis enhanced with oral and intravenous contrast. Target lesion (arrow) suggests terminal ileum wall thickening, while mesentery of the distal small bowel demonstrates mesenteric stranding.

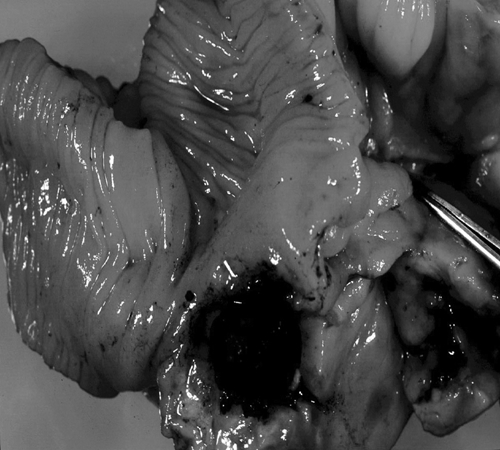

The patient was taken to the operating room with an acute abdomen and abnormalities on CT felt to be an intussuception. At the time of operation, 34 cm of ileum and 5 cm of cecum were resected, allowing the removal of a large inflammatory mass (Fig. 2). The patient recovered without incident and was discharged from hospital 10 days later.

FIG. 2. A resection of distal small bowel. Approximately 5.0 cm from the proximal margin (34.0 cm from the terminal ileum) is an out-pouching of the small bowel that is occluded in the neck area by a fecalith measuring 1.5 cm. Distal to the fecalith (not shown) is a thick walled cavity lined with edematous bowel wall and firm fatty tissue.

The pathology report showed an acute inflammatory mesenteric mass with a Meckel's diverticulum obstructed by a fecalith, leading to ulceration and perforation. Acute serositis with hemorrhage and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia was also present in the region of the Meckel's diverticulum. The Meckel's diverticulum was found 30.0 cm from the terminal ileum on the mesenteric side, which is unusual but still consistent with the diagnosis.

Case 2: hemorrhage

A 31-year-old previously healthy man presented with bright red blood per rectum of 4 days duration, increasing light-headedness, shortness of breath, palpitations, headache and fatigue. There was no history of melena, constipation or previous episodes. Examination showed a hemodynamically unstable patient with a hemoglobin level of 47 g/L. The patient was aggressively resuscitated for a presumed lower gastrointestinal bleed. No evidence of active hemorrhage was noted on initial investigation, endoscopy, mesenteric angiogram or colonoscopy. A Meckel's scan was found to be positive, showing the region of uptake just above the bladder (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3. Meckel's scan. A focus of abnormal radiotracer uptake is demonstrated in the lower abdomen several centimetres above the dome of the bladder. In this clinical situation the appearance is consistent with a Meckel's diverticulum containing ectopic gastric mucosa.

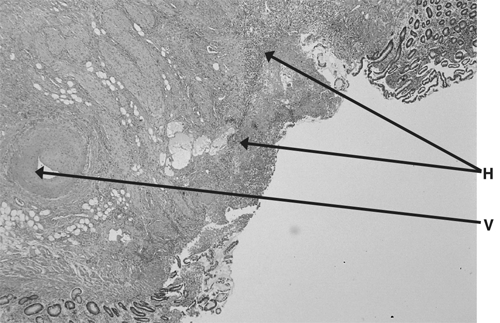

The patient was taken to the operating room, and a 2-inch Meckel's diverticulum was resected, along with 10.0 cm of small bowel. The patient recovered without incident and was discharged from the hospital 5 days later. The pathology report showed a Meckel's diverticulum with peptic ulceration present at the base (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4. Small bowel mucosa with hemorrhagic ulceration (H) and a feeder vessel (V).

Case 3: obstruction due to lipoma

A 38-year-old man with no previous abdominal surgery presented with a 24-hour history of crampy abdominal pain, fever, chills, nausea and vomiting. Examination of the abdomen showed marked distension with peritonitis. The following abdominal x-ray (Fig. 5) showed multiple air-fluid levels and grossly dilated small bowel.

FIG. 5. Upright abdominal x-ray showing dilated loops of small bowel with multiple air fluid levels.

The patient was taken to the operating room for emergency laparotomy and was found to have a large ileal intussusception. A gentle reduction of the intussusception demonstrated a large polypoid mass attached to a 6-cm stalk within the lumen of the ileum. The stalk originated at an inverted Meckel's diverticula along the antimesenteric border of the bowel (Fig. 6). A resection and functional end-to-end anastamosis of the bowel was completed. The patient recovered without incident and was discharged after 5 days in hospital.

FIG. 6. Intussuscepted portion of small bowel exposing an inverted Meckel's diverticulum (3.3 cm in length). Projecting from the tip is a firm hemorrhagic mass with ulcerations. Sectioning of the mass reveals a lipoma (3.9 × 1.5 × 1.9 cm).

The pathology report showed an inverted Meckel's diverticulum with a firm hemorrhagic mass (4.5 × 2.3 cm) and ulcerations projecting from the tip of the diverticulum. On sectioning the hemorrhagic mass, histopathology investigations revealed it to be a benign lipoma with granulation tissue formation.

Case 4: neoplasm, carcinoid

A 16-year-old previously healthy male presented with a 3-day history of fever (38.7°C), nausea, vomiting and constant right lower-quadrant pain. Examination revealed a diffusely tender abdomen, and laboratory tests demonstrated a white blood cell count of 15.4 × 109/L.

The patient was taken immediately to the operating room for laparotomy. A perforated retrocecal appendix with abscess was found, drained and resected. A Meckel's diverticulum was also identified and felt to have a small polypoid mass; this was resected and sent to pathology. The patient was closed and recovered without incident.

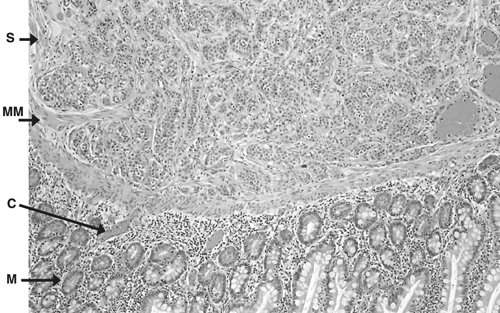

The pathology report showed a Meckel's diverticula on the antimesenteric border, with small foci of carcinoid tumour less than 0.2 cm in diameter (Fig. 7). This tumour involved only the lamina propria and submucosal layers, and all margins were clear.

FIG. 7. Normal histology of the Meckel's diverticula, with small foci of carcinoid tumour. Normal mucosa (M) and normal submucosa (S), separated by muscularis mucosa (MM). Several small foci (< 0.2 cm each) of carcinoid tumour (C) are identified at the interface of the lamina propria and sub mucosa. The tumour does not invade the luminal surface or extend into the muscularis propria.

Discussion

The total lifetime rate of complications is widely accepted at 4%,8,20 with a male-to-female ratio ranging from 1.8:1 to 3:1.3,8,11,19,21,22 The largest study, by Yamaguchi and colleagues,14 with 600 patients, 287 of whom were symptomatic, showed the following complication rates: obstruction, 36.5%; intussusception, which often presents as obstruction, 13.7%; inflammation or diverticulitis and perforation, 12.7% and 7.3%, respectively; hemorrhage, 11.8%; neoplasm, 3.2%; and fistula, 1.7%. The 4 cases discussed here demonstrate the presenting symptomatology and pathology of the most common complications of Meckel's diverticula.

Intestinal obstruction is the most common complication in adult patients, with incidence rates varying from 22% to just over 50%.8,11,13,14,17,20 The series by Yamaguchi and colleagues,14 which comprised nearly 50% adults, showed hemorrhage as being less common than obstruction at a rate of almost 5:1 (54%:12%). The most common obstruction was intussusception or invagination, with the Meckel's diverticulum being the lead point.11,14 Other causes of obstruction include volvulus around fibrous bands adherent to the umbilicus, inflammatory adhesions, Littre's hernias and diverticular strictures.5,11,14,17 Some other uncommon causes of obstruction found in the literature include enteroliths being expulsed from the diverticulum and forming a distal obstruction23 and loop formations with the end of a Meckel's diverticulum and adjacent mesentery incarcerating the distal ileum.24

The second most common complication in adults appears to be related to an inflammatory process. Diverticulitis and perforation occur at a combined rate of almost 20% and are often indistin-guishable from acute appendicitis until visualization in the operating room.14 Moore and Johnston25 reported that 40% of patients in a series of 50 patients with Meckel's diverticulum had a preoperative diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Initially, a fecalith obstructs the diverticulum, leading to inflammation, necrosis and eventual perforation. Additional complications of the perforation include both abscess and fistula formation.These complications are often seen in association with Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis.7,26–28 More rarely, Meckel's diverticulum can be perforated by foreign bodies, including fish bones, marbles, gallstones, toothpicks and even bullets.12,29–32

Hemorrhage is the most common presentation in children and is reported in over 50% of cases.33 In adults, hemorrhage occurs often but is the presenting complaint in only 11.8%.14 Children often present with dark red or maroon stools or stools with blood or mucus, whereas adults usually present with melena and crampy abdominal pain. This is felt to be owing to a slower colonic transit time in adults.4,13 Ninety percent of bleeding diverticula contain heterotropic mucosa, most often gastric mucosa.5,34 This mucosa allows the diverticulum to be picked up radiologically by a Meckel's scan. The 99m Tc-pertechnetate Meckel's scan is designed to detect gastric mucosa of at least 1.8 cm2.35 The reported accuracy of 46% in an adult series36 is much lower than that in children but can theoretically be increased by the use of adjunctive agents. Pentagastrin accelerates Tc uptake and Cimetidine decreases Tc release by the gastric mucosa.37–39 H. pylori has been unquestionably linked with the ulceration of gastric mucosa in the stomach and duodenum, but more recent literature suggests that it likely plays no role in bleeding Meckel's diverticula.5,40 Neoplasm is reported at a rate of 3.2%, with carcinoid tumours comprising 33% of these cases.11,41–43 Other reported cases include sarcomas, adenocarcinomas, benign mesenchymal tumours, melanoma, lymphoma, phytobezoars and lipomas.5,12,44,45

Management

Treatment of symptomatic Meckel's diverticulum has always been surgical resection. Over the last several years, there has been debate about the proper management of asymptomatic Meckel's diverticula discovered during laparotomy or laparoscopy. Incidence and prevalence figures quoted are uniform across most studies and are based on autopsy reports; conversely, complication rates have varied. Soltero and colleagues20 estimated the lifetime risk of having a Meckel's diverticulum to be 4.2%, decreasing with age. By 76 years of age, the risk would be 0%. It was concluded that 800 people with asymptomatic Meckel's diverticulum would need to be treated to prevent 1 death.8,11,20 At that time, the mortality from a diverticulectomy was estimated to be approximately 7%, thus prophylactic removal was discouraged.13,14 More recently, Cullen and others19 conducted an epidemiological study at the Mayo clinic in Minnesota that reached differing results. They found the incidence of complications requiring surgery to be 6.4%, with no trend related to age. The mortality rate of these patients was 1.5%, with 7% morbidity; incidental removal had 1% mortality and 2% morbidity. This led them to claim that incidental diverticulectomy was warranted.

At our institution, we base the decision to resect an asymptomatic Meckel's diverticulum on a case-by-case basis. Factors that would lead us to perform a resection include the following: younger age at presentation, narrow diverticular neck, previous abdominal adhesions or obstructions, and any palpable or visual abnormality of the Meckel's diverticulum. Factors that would discourage the resection include older age at presentation, wide diverticular neck and the absence of other abdominal pathology. A good review of this controversial topic can be found in the article by Yahchouchy and others.5

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Daphne Mew, University of Calgary Faculty of Medicine, Department of Surgery, 3330 Hospital Drive NW, Calgary AB T2N 4N1; dmew@ucalgary.ca

References

- 1.Meckel JF. Uber die divertikel am darmkanal. Arch Die Physio 1809;9:421-53.

- 2.Kuwajerwala NK, Silva YJ. Meckel diverticulum. Available from: http://www.emedicine.com/med/topic2797.htm. Accessed March 2001.

- 3.Stone PA, Hofeldt MJ, Campbell JE, et al. Meckel diverticulum: ten-year experience in adults. South Med J 2004;97:1038-41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Turgeon DK, Barnett JL. Meckel diverticulum. Am J Gastroenterol 1990;85:777-81. [PubMed]

- 5.Yahchouchy EK, Marano AF, Etienne JCF, et al. Meckel's diverticulum. J Am Coll Surg 2001;192:658-62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Martin JP, Connor PD, Charles K. Meckel's diverticulum. Am Fam Physician 2000;61:1037-42. [PubMed]

- 7.DiGiacomo JC, Cottone FJ. Surgical treatment of Meckel's diverticulum. South Med J 1993;86:671-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Leijonmarck CE, Bonman-Sandelin K, Frisell J, et al. Meckel diverticulum in the adult. Br J Surg 1986;73:146-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Ludtke FE, Mende V, Kohler H, et al. Incidence and frequency of complications and management of Meckel's diverticulum. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1989;169:537-42. [PubMed]

- 10.Harkins HN. Intussusception due to invaginated Meckel's diverticulum. Ann Surg 1933;98:1070-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Mackey WC, Dineen P. A fifty year experience with Meckel's diverticulum. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1983;156:56-64. [PubMed]

- 12.Moses WER. Meckel's diverticulum: a report of two unusual cases. N Engl J Med 1947;237:118-22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Weinstein EC, Cain JC, Remine W. Meckel diverticulum: 55 years of clinical and surgical experience. JAMA 1962;182:251-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Yamaguchi M, Takeuchi S, Awazu S. Meckel diverticulum. Investigation of 600 patients in the Japanese literature. Am J Surg 1978;136:247-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Arnold JF, Pellicane JV. Meckel's diverticulum: A Ten-year experience. Am Surg 1997;63:354-5. [PubMed]

- 16.Michas CA, Cohen SE, Wolfman EF Jr. Meckel's diverticulum: should it be excised incidentally at operation? Am J Surg 1975;129:682-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Pinero A, Martinez-Barba E, Canteras M, et al. Surgical management and complications of Meckel's diverticulum in 90 patients. Eur J Surg 2002;168:8-12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Williams RS. Management of Meckel's diverticulum. Br J Surg 1981;68:477-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Cullen JJ, Kelly KA, Moir CR, et al. Surgical management of Meckel's diverticulum. An epidemiologic, population-based study. Ann Surg 1994;220:564-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Soltero MJ, Bill AH. The Natural history of Meckel diverticulum and its relation to incidental removal. Am J Surg 1976;132:168-73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Groebli Y, Bertin D, Morel P. Meckel diverticulum in adults: Retrospective analysis of 119 cases and historical review. Eur J Surg 2001;167:518-24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Peoples JB, Lichtenberger EJ, Dunn MM. Incidental Meckel diverticulectomy in adults. Surgery 1995;118:649-52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Gamblin TC, Glenn J, Herring D, et al. Bowel obstruction caused by a Meckel's diverticulum enterolith: a case report and review of the literature. Curr Surg 2003;60:63-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Tomikawa M, Taomoto J, Saku M, et al. A loop formation of Meckel's diverticulum: a case with obstruction of the ileum. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2003;9:134-6. [PubMed]

- 25.Moore T, Johnston OB. Complications of Meckel's diverticulum. Br J Surg 1976;63:453-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Cunnick GH, Richardson NG, Ratcliffe N, et al. Acute ulcerative colitis in a Meckel's diverticulum. Int J Clin Pract 2004;58:422-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Hudson HM 2nd, Millham FH, Dennis R. Vesico-diverticular fistula: a rare complication of Meckel's diverticulum. Am Surg 1992;58:784-6. [PubMed]

- 28.Mourra N, Tiret E, Caplin S, et al. Involvement of Meckel diverticulum in Crohn disease associated with pancreatic heterotopia. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2003;127:E99-E100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Christensen H. Fishbone perforation through a Meckel's diverticulum: a rare laparoscopic diagnosis in acute abdominal pain. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 1999;9:351-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Greenspan L, Abramovitch A, Tomarken J, et al. Perforation of a Meckel's diverticulum by a foreign body. Can J Surg 1983;26:184-5. [PubMed]

- 31.Yagci G, Cetiner S, Tufan T. Perforation of Meckel's diverticulum by a chicken bone, a rare complication: Report of a case. Surg Today 2004;34:606-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Zingg U, Vorburger S, Metzger U. Perforation of a Meckel's diverticulum by a toothpick. Chirurg 2000;71:841-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Rutherford RB, Akers DR. Meckel diverticulum: a review of 148 pediatric patients with specific reference to the pattern of bleeding and to mesodiverticular vascular bands. Surgery 1966;59:618-26. [PubMed]

- 34.Berman EJ, Shnider A, Potts WJ. Importance of gastric mucosa in Meckel's diverticulum. JAMA 1954;156:6-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Priebe CJ, Marsden DS, Lazarevic B. The use of 99m-technetium pertechnetate to detect transplanted gastric mucosa in the dog. J Pediatr Surg 1974;9:605-13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Schwartz MJ, Lewis JH. Meckel's diverticulum: pitfalls in scintigraphic detection in the adult. Am J Gastroenterol 1984;79:611-8. [PubMed]

- 37.Anderson DJ. Carcinoid tumour in Meckel's diverticulum: laparoscopic treatment and review of the literature. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2000;100:432-4. [PubMed]

- 38.Petrokubi RJ, Braum S, Rohrer GV. Cimetidine administration resulting in improved pertechnetate imaging of Meckel's diverticulum. Clin Nucl Med 1978;3:385-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Rossi P, Gourtsoyiannis N, Bezzi M, et al. Meckel's diverticulum: imaging diagnosis. AJR 1996;567-573. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Chan GS, Yuen ST, Chu KM, et al. Helicobacter pylori in Meckel's diverticulum with heterotropic gastric mucosa in a population with relatively high H. Pylori prevalence rate. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999;14:313-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Warner RRP. Carcinoid tumour. In: Berk EJ, ed. Bockus, Gastroenterology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1985;19874-85.

- 42.Dixon AY, McAnaw M, McGregor DH, et al. Dual carcinoid tumours of Meckel's diverticulum presenting as metastasis in inguinal hernia sac: case report with literature review. Am J Gastroenterol 1988;83:1283-7. [PubMed]

- 43.Weistein EC, Docherty MB, Waugh JM. Neoplasms of Meckel's diverticulum. Int Abstr Surg 1963;116:103-11.

- 44.Arteaga Martin X, Elorza Orue JL, Busto Vicente MJ, et al. Meckel's diverticulum adenocarcinoma: a rare malignant degeneration. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2003;95:660-1,658-61. [PubMed]

- 45.Ahmed HU, Wajed S, Krijgsman B, et al. Acute abdomen from a Meckel lipoma. J R Soc Med 2004;97:288-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]