MFRP is expressed in the RPE, but its mutations in mice lead to photoreceptor degeneration. The authors describe a new null mutation in mouse MFRP that also leads to RPE atrophy, suggesting that it may provide a useful model for advanced macular degeneration with geographic atrophy in humans.

Abstract

Purpose.

The authors have identified a recessive mutation causing progressive retinal degeneration, white fundus flecks, and eventual retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) atrophy. The goal of these studies was to characterize the retinal phenotype, to identify the causative locus, and to examine possible functions of the affected gene.

Methods.

SNP mapping, DNA sequencing, and genetic complementation were used to identify the affected locus. Histology, electroretinography, immunohistochemistry, Western blot analysis, fundus photography, electron microscopy, and in vitro phagocytosis assays were used to characterize the phenotype of the mouse.

Results.

Gene mapping identified a single base pair deletion in membrane-type frizzled related protein (MFRP), designated Mfrp174delG. MFRP is normally expressed in the RPE and ciliary body but was undetectable by Western blot in mutants. CTRP5, a binding partner of MFRP, was upregulated at the mRNA level and at the protein level in most patients. Assays designed to test the integrity of retinoid cycling and phagocytic pathways showed no deficits in Mfrp174delG or rd6 animals. However, the RPE of both Mfrp174delG and rd6 mice exhibited a dramatic increase in the number of apical microvilli. Furthermore, evidence of RPE atrophy was evident in Mfrp174delG mice by 21 months.

Conclusions.

The authors have identified a novel null mutation in mouse Mfrp. This mutation causes photoreceptor degeneration and eventual RPE atrophy, which may be related to alterations in the number of RPE microvilli. These mice will be useful to identify a function of MFRP and to study the pathogenesis of atrophic macular degeneration.

Membrane-type frizzled related protein (MFRP) is a type II transmembrane protein that was first identified based on its C-terminal cysteine-rich domain.1 The rd6 mouse has a 4-base pair (bp) deletion at the 5′ end of the fourth intron, resulting in improper splicing.2 Rd6 mice have white flecks distributed evenly across the fundus that can be viewed ophthalmoscopically and that are correlated with aberrant cells in the subretinal space. The photoreceptors in these animals degenerate slowly, beginning by weaning age and continuing over at least 2 years.3 MFRP has also been implicated in human disease. Humans with mutations in MFRP have nanophthalmia and are extremely hyperopic,4 although the phenotype with regard to the retina appears to be variable. In one study, ERGs of hyperopic members of an Amish-Mennonite kindred were reported as normal.4 However, several other studies5,6 reported extensive evidence of retinitis pigmentosa, foveoschisis, and optic disc drusen in families with MFRP mutations. Notably, there was no mention of fundus flecks in any of the human patients. The partial phenotypic dichotomy between the human and mouse mutations has yet to be fully explained.

Although earlier studies have clearly demonstrated that Mfrp is required for normal development and function of the visual system, we have very little insight into the function of this protein at the molecular level. Its expression in the eye is restricted to the apical retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and the ciliary body epithelium,7 suggesting that photoreceptor disease in mutants may be secondary to disruptions in the RPE. Its extracellular C-terminal domain is conserved with Frizzled, the canonical wnt receptor, but studies addressing the possibility that MFRP is a wnt receptor are inconclusive.2 Its proximal extracellular region consists of a tandem repeat of CUB-LDLR domains homologous to Tolloid metalloproteases,8 but there is no evidence that the protein exhibits proteolytic activity. Rather, this region has been shown to bind CTRP5, a secreted protein that is highly expressed in the RPE.7,9 CTRP5 is composed of an N-terminal collagen repeat and a C-terminal c1q domain and is expressed in a wide variety of tissues. A mutation in the c1q domain of CTRP5 causes late-onset macular degeneration in humans,10 but the phenotype is distinct from that caused by MFRP mutations, suggesting that the two proteins can function independently. CTRP5 is a member of a large family of similar proteins, and there is evidence that CTRP1 may play a role in metabolic regulation.11 Recent evidence indicates that CTRP5 activates AMPK in L6 myoblasts,12 and that it is regulated by HNF4α in SK-Hep1 cells.13 However, a specific role for CTRP5 in the eye has yet to be discovered. Additional studies have suggested that MFRP may play a role in outer segment phagocytosis.14

Here we report the discovery of a novel null mutation in mouse Mfrp that causes a phenotype similar to that reported for rd6. These animals have fundus flecks and slow photoreceptor degeneration as in rd6, but, unlike rd6 mice, also show evidence of RPE atrophy in older animals. This makes our model comparable to human MFRP-related disease, which in one study was also reported to include atrophy of the pigmented layers of the retina.5 Evaluation of the RPE before atrophy showed that the number of microvilli is highly upregulated in mutant animals. However, we did not detect any deficiencies in RPE phagocytosis using an in vitro approach. These animals will be valuable in the effort to elucidate the molecular function of MFRP and to understand the pathogenesis of photoreceptor degeneration in humans with MFRP mutations and related diseases.

Methods

Preliminary tissue collections were carried out at the University of Massachusetts Medical School (Worcester, MA), and remaining experiments were conducted at the Medical College of Wisconsin. All experiments were performed in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and were approved by the institutional animal care and use committees of the Medical College of Wisconsin and the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Histology

Eyes were enucleated, punctured through the cornea with a fine scissors, and fixed overnight in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer containing 2% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde. After fixation, the cornea, iris, and lens were removed, and the eye was bisected along the dorsoventral meridian. Aldehydes were then removed by overnight incubation in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, followed by postfixation in 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 hour and dehydration in a graded methanol series. Eyes were embedded in embedding resin (Embed 812; Electron Microscopy Systems, Hatfield, PA) such that they could be sectioned along the dorsoventral meridian that was exposed when they were bisected. One-micrometer sections were cut and stained with toluidine blue for light microscopy.

Fundus Photography

Eyes were dilated with 1% atropine (Midwest Veterinary Supply, Burnsville, MN), and fundus images were captured with a handheld fundus camera (Genesis; Kowa Optimed, Torrance, CA) and a 70-D lens (Volk, Mentor, OH).

Electroretinography and Rhodopsin Measurements

Animals were dark adapted overnight, and all manipulations were performed under dim red light. Eyes were dilated with 1% atropine, and the animals were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO; 120 mg/kg and 18 mg/kg, respectively). A subdermal reference electrode (Grass Technologies, West Warwick, RI) was placed in either the cheek or the scalp, and a contact lens recording electrode (LKC Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) was lubricated with methylcellulose and placed on the cornea. ERGs were recorded (UTAS-3000; LKC Technologies). Scotopic responses were measured between −3.2 and 0.6 log cd · s · m−2, and photopic responses were measured between −1 and 1.6 log cd · s · m−2, with 1.4 log cd/m−2 background illumination. Scotopic double-flash ERGs were performed as described,15 although both test and probe flashes were given at 0.6 log cd · s · m−2. Rhodopsin content in homogenized retinas was measured as described.16

Gene Mapping and Genotyping

Affected animals on the parental 129/Sv background were crossed to C57Bl/6J, and the resultant pups were sib-crossed to produce the F2 generation. F2 pups were screened by ERG to identify animals with depressed a-waves. Genomic DNA from these animals was screened with a genomewide SNP panel administered by the Partners Health Care Center for Personalized Genetic Medicine to identify linked loci.17 Exons of candidate genes in the identified interval were sequenced using BigDye version 1.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on an automated sequencer (ABI310; Applied Biosystems). Genotyping to distinguish wild-type and Mfrp174delG alleles was performed by PCR on genomic DNA using primers 5′-AAGCCCACTGTGTCCTCCCTACAGCCCAGCGCCTCC-3′ and 5′-GCCTGCAACTCTGGAGGCTAGGTATAGAGG-3′, followed by digestion of the amplimer with BglI. A BglI site in the amplimer from the Mfrp174delG allele cleaves the 249-bp amplimer, yielding a 212-bp product.

Antibodies

Antibodies used included anti-MFRP and anti-CTRP5 goat polyclonals (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN); anti-Na/K ATPase α1 subunit mouse monoclonal α6F (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA); anti-actin mouse monoclonal and anti-ezrin rabbit polyclonal (Millipore, Bedford, MA); anti-F4/80 rat monoclonal (Serotec, Raleigh, NC); anti RPE-65 rabbit polyclonal (generous gift of T. Michael Redmond); and anti ZO-1 rabbit polyclonal (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Appropriate secondary antibodies for immunofluorescence were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA), and Western blot secondary antibodies were obtained from Li-Cor Technologies (Lincoln, NE). Optimal antibody titers were determined empirically for all applications.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Three to five mice per genotype were used at 8 months of age. Animals were euthanatized with CO2 followed by cervical dislocation, and eyes were removed. The cornea, iris, and lens were removed, and the eyecup was incubated in 1% hyaluronidase (Sigma) for 30 minutes. The neural retina was then removed. RNA was purified from the remaining eyecup using a mini kit with on-column DNase digestion (RNeasy; Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA was synthesized (iScript kit; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and quantitative PCR was performed (iCycler; Bio-Rad) using supermix (iQ-Sybr Green; Bio-Rad). We used primers for Mfrp7, Ctrp5 (5′- AGAGAAAGGCGAGGGCGGGAGAC-3′; 5′- ACTGGAAGAAAGAGGCGATGGACT-3′), and Gapdh (5′-AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG-3′; 5′-GCATGCAGGGATGATGTTCT-3′). Fold change in Mfrp and Ctrp5 transcripts was calculated according to the method of Pfaffl18 and normalized to Gapdh.

Western Blot Analysis

Whole mouse eyes were dissected to remove the cornea, iris, and lens, and the remaining analysis were performed according to standard procedures. Blots were probed with fluorescent secondary antibodies and detected with an infrared imager (Odyssey; Li-Cor).

Immunohistochemistry

Eyes were dissected in PBS to remove the anterior segment. Remaining eyecups were fixed for 10 minutes in PBS + 4% paraformaldehyde and were placed in methanol overnight at 4°C. Tissues were then transferred to PBS + 50% methanol + 20% sucrose at 4°C for 1 hour and were twice incubated for 30 minutes in PBS + 20% sucrose at 4°C with rotation. Eyecups were infiltrated with 50% tissue freezing medium (Triangle Biomedical Sciences, Durham, NC) + 15% sucrose in PBS for 2 hours at 4°C and then in 100% tissue freezing medium for 1 hour at room temperature with rotation before embedding. Sections measuring 5 to 10 μm were cut on a cryostat (HM550; Thermo Scientific), bleached in 1× SSC containing 5% formamide and 5% peroxide, immunostained according to standard procedures, and viewed with a fluorescence microscope (TE300; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). ZO-1 staining was performed on RPE explants prepared and imaged as described for phagocytosis assays. F4/80 immunostaining was performed on whole, unfixed eyecups from which the retina had been removed. After immunostaining, the tissue was briefly postfixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and flat-mounted for imaging.

In Vitro Phagocytosis Assays

Primary RPE cultures and phagocytosis assays were performed as previously described.19 Briefly, primary RPE cultures from p10 to p13 pups were prepared and cultured for 5 to 7 days. Cells were fed with FITC-labeled porcine outer segments for 2 hours before they were washed to remove excess material and were fixed in cold methanol. Immunostaining with ZO-1 antibody was performed by standard procedures. Cultures were imaged with a laser scanning confocal microscope (TCS-SP2; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Particle counting was performed on maximum z-projections from four to six fields using ImageJ software (developed by Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/index.html). Only fields containing cells with well-defined cell junctions were used for analysis, and cell size did not differ significantly with genotype. Phagosome images were thresholded, and the analyze particles function in ImageJ was used to count phagosomes larger than 1 μm2. Comparisons were conducted with one-way ANOVA. Confocal analysis indicated that >90% of visible FITC-positive material was basal to ZO-1 staining; therefore, we did not distinguish between surface-bound and internalized material in these experiments.

RPE Ultrastructure and Microvillus Density

Eyes were dissected to remove the cornea, iris, and lens and were then placed in Ca-Mg-free HBSS (Invitrogen) containing 1 mg/mL hyaluronidase (Sigma) at room temperature for 40 minutes. After this treatment, the retina was gently removed with forceps and was closely examined to ensure that no pigmented tissue was removed with it. The remaining eyecup was fixed and embedded in plastic as described. Thin sections were cut and stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate according to standard procedures and were viewed with a transmission electron microscope (H600 TEM; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). A stretch of RPE at least 250 μm in length in the midperiphery was imaged at 5000× to 8000× magnification with a digital camera. Images were then assembled into large montages in Adobe Photoshop. In a separate layer of the montage, small dots were placed over areas where microvilli were observed to bud off the apical membrane. This “dot” layer was rotated to be roughly vertical and then was imported into ImageJ, which was used to assign coordinates to the centroid of each dot. The distance between adjacent dots was calculated by triangulation, and these data were used to generate a linear array representing the location of microvillar buds along the apical membrane. This array was then split into 25-μm sections, and the number of points per section was averaged across the entire array. We used three biological replicates for each mouse type.

Results

Identification of Founder Animals with Retinal Defects

A subset of mice with retinal degeneration was identified in a histologic screen of Per3−/− animals on a 129/Sv background20 from a colony maintained at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. The degeneration was limited to the outer layers of the retina and was uniform from the center to the periphery (Figs. 1A–C). Additional screening of more animals from this colony showed that a subpopulation of animals, designated Per3−/−sp2, had abnormal electroretinograms (ERG) with nearly complete loss of the a-wave (Fig. 1D). Outcrossing of affected animals to C57Bl/6J mice followed by sib-crossing showed that the retinal phenotype was inherited recessively and segregated independently of the Per3 mutation from the parental strain (data not shown). To further study the retinal degeneration phenotype, we established a new line of C57/129 hybrid animals that carried the wild-type Per3 gene while still manifesting the mutant ERG phenotype, designated this line rdx, and maintained it by sib-crosses.

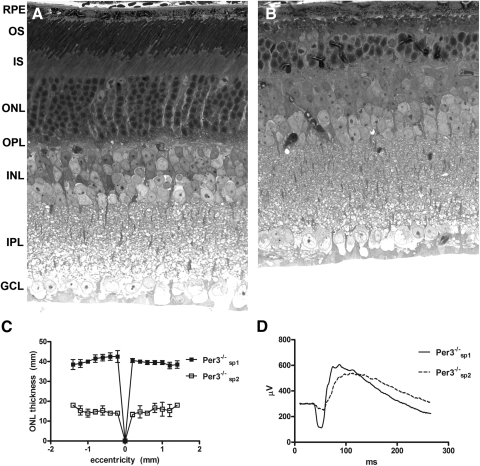

Figure 1.

Representative images of 10-month-old normal (A) and degenerate (B) retinas observed among Per3−/− mice. Note the dramatic thinning of the outer layers of the retina. OS, outer segments; IS, inner segments; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. ONL thickness as a function of retinal eccentricity is shown in (C) for 10-month-old animals (n = 3). Remaining animals in the colony were screened by ERG and separated into two subpopulations, which we designated Per3−/−sp1 and Per3−/−sp2 (D). Normal animals (Per3−/−sp1) had a robust a-wave, whereas affected animals (Per3−/−sp2) showed significant a-wave attenuation. ERGs are averages of four to six animals between 6 and 8 weeks of age that were dark adapted for 2 hours and recorded after a single flash of intensity sufficient to evoke the maximum response.

rdx Mice Have Flecked Retina Disease and a Slow Retinal Degeneration

Histologic analysis showed disorganized outer segments as early as 3 weeks, with thinning of the outer nuclear layer (ONL) evident by 6 weeks and progressing slowly through 12 months, when approximately 80% of the photoreceptor nuclei had been lost (Fig. 2A). Aberrant pigmented cells among the distal tips of the outer segments were routinely seen in mutant animals by 3 months, although they were observed sparingly as early as 10 days. By 21 months, no photoreceptors remained, and focal areas of degenerate RPE were noted (Fig. 2B). White subretinal flecks, observed by fundus photography, first appeared around 3 months, were widespread and regularly spaced across the entire fundus by 4 months, and were unapparent by 9 months. By 21 months, large regions of fundus hypopigmentation were observed, similar to geographic atrophy in humans and consistent with loss of RPE confluence at this stage (Fig. 2C). Scotopic ERGs showed complete or near-complete loss of the a-wave at all time points beginning at 10 weeks, accompanied by more modest but significant b-wave attenuation. In contrast, photopic responses were largely preserved until at least 6 months (Fig. 2D).

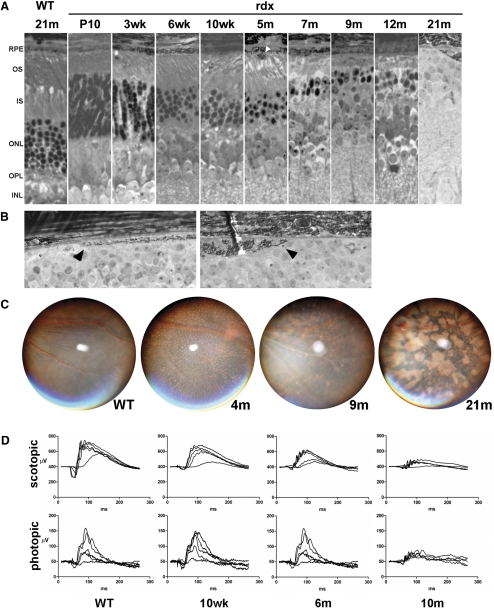

Figure 2.

(A) rdx animals exhibit progressive retinal degeneration. Note the presence of an aberrant pigmented cell among the distal tips of the outer segments at 5-months (white arrowhead). (B) In an advanced stage of the disease, we noted focal areas of RPE degeneration. Images are from two different animals at 21 months. (arrows) RPE cells at the edge of atrophic regions. (C) White flecks appear widespread on fundus examination between 2 and 4 months but disappear as the animals age. Fundi from older animals exhibit abnormal pigmentation similar to that in patients with geographic atrophy of the RPE. (D) Electroretinograms from C57-hybridized rdx mice retain the characteristics of the isogenic parental 129 strain seen in Figure 1. In scotopic measurements, total amplitude is decreased and the a-wave is greatly diminished. Photopic responses are largely unaffected until at least 6 months. Multiple traces are responses at increasing stimulus intensities.

As illustrated sequentially in Figure 3, we were able to directly correlate the flecks that were observed by fundus photography with the pigmented cells in the subretinal space (Figs. 3A–D). A similar pattern of flecks was visible using a dissecting microscope in eyecups after removal of the anterior segment (Fig. 3A) and in association with RPE after removal of the retina (Fig. 3B). These structures correlated with pigmented cells adjacent to the RPE in both light microscopic (Fig. 3C) and electron microscopic images (Fig. 3D). Given the evidence of RPE atrophy, we considered the possibility that the subretinal cells were actually delaminated cells of RPE origin. However, our data suggest that they were, in fact, macrophages because they failed to stain with RPE65 (Fig. 3E) but did stain positively for the macrophage marker F4/80 (Fig. 3F). Similar F4/80+ cells were observed in wild-type eyecups, but they were at a very low density (4–5 cells per eye) and exhibited significantly less autofluorescence than F4/80+ cells in mutant eyecups (Fig. 3G).

Figure 3.

Direct observation and analysis of subretinal flecks. White subretinal flecks were observed in a Mfrp174delG mouse by fundus photography (see Fig. 2C). (A) Eyes were then dissected to remove the cornea, iris, and lens. White spots were still visible through the retina with a dissecting microscope (black arrowheads). (B) After the retina was removed, the white structures remained adherent to the RPE and were more clearly imaged (white arrowheads). These structures were absent in regions where the RPE was peeled off during dissection, exposing the underlying choroid (asterisk). (C) The tissue was then processed and embedded in plastic for electron microscopy. One-micrometer sections revealed that the structures were clearly cellular in nature (arrowhead). (D) When viewed at the electron microscope level, we observed that the cells contained pigment granules and small, circular, membranous structures. (E) Frozen sections of eyes with retinas removed were probed with an RPE65 antibody (green), which labeled RPE but not the adjacent subretinal cells (arrowheads). Note that nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue). (F) Flat-mounted eyecups with retinas removed were used to test for immunoreactivity with macrophage marker F4/80 (green). Subretinal cells in this preparation were highly autofluorescent (red), making them easy to identify. (G) F4/80+ cells in wild-type eyecups were sparse and much less autofluorescent. mv, microvilli; ch, choroid; POS, photoreceptor outer segment.

rd6 and rdx Are Allelic

We took advantage of the robust “loss of a-wave” phenotype to determine the genetic basis of the observed inherited retinopathy. Our population of C57-outcrossed rdx animals were screened by ERG to identify affected individuals and were then genotyped across a genomewide panel of 511 informative SNPs with an average spacing of 4.9 Mb.17 This analysis positionally cloned the mutation to a 25-Mb interval on chromosome 9 between rs4227585 and rs4227682 (Fig. 4A). Although many genes are present in this interval, Mfrp and Ctrp5 are located in tandem within this region and were investigated as strong candidates because they have been previously linked to inherited retinal diseases. They have been reported to be expressed as a bicistronic transcript,2 and a splice site mutation in the rd6 mouse that deletes exon 4 from the mature Mfrp transcript results in flecked retina disease with progressive retinal degeneration.2 Similarly, an S163R substitution in human CTRP5 causes late-onset macular degeneration in humans and mice.10,21 Sequencing of the coding regions of these two genes from rdx mice identified a single base pair deletion in exon 3 of Mfrp, which we designated Mfrp174delG (Fig. 4B). We then developed a PCR-RFLP genotyping assay to identify this allele (Fig. 4C). Finally, to confirm that rd6 and Mfrp174delG are indeed allelic, we performed a genetic complementation test using homozygous rd6 mice obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Of 27 Mfrprd6/174delG mice produced and examined by fundus photography at 2.5 to 3 months of age, all exhibited signs of flecked retina disease (Fig. 4D). Phenotypic analysis of offspring from multiple homozygous Mfrp174delG crosses confirmed that the fundus fleck and retinal degeneration phenotypes described are 100% penetrant in Mfrp174delG/174delG animals. If translated to a stable protein, the Mfrp174delG allele is predicted to encode only the cytosolic N terminus, followed by 83 nonsense residues. In contrast, the rd6 allele deletes a region between the transmembrane domain and the first CUB domain, without disrupting C-terminal structures (Fig. 4E). After identification of the genetic basis of this phenotype, Per3−/− mice on the original 129/Sv background were bred to select against the Mfrp174delG allele, and the resultant Per3−/− Mfrp+/+ mice were deposited at The Jackson Laboratory (strain 010833).

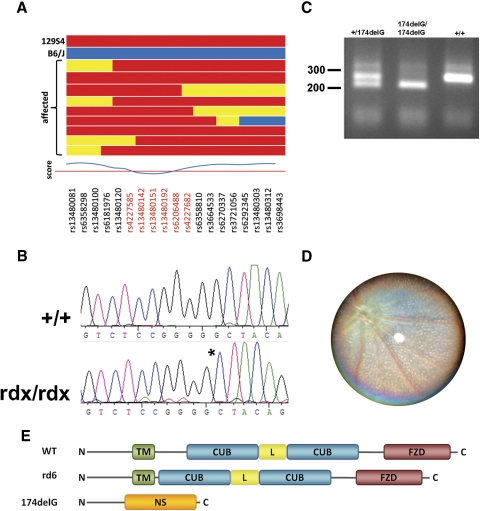

Figure 4.

(A) rdx maps to a 25-Mbp region on chromosome 9. (horizontal bars) Genotypes of individual animals at the loci indicated along the bottom. (red) 129S4. (blue) C57Bl/6J. (yellow) Heterozygous. Loci in red fell within the linkage region. (B) Sequencing of candidate genes identified a single nucleotide deletion in exon 3 of MFRP, denoted by the asterisk. (C) PCR-RFLP genotyping of genomic DNA distinguishes Mfrp174delG and wild-type alleles. (D) A genetic complementation experiment produced 27 Mfrp174delG/rd6 hybrid animals that manifested the same fundus phenotype as both parental strains. A fundus image of a representative 2.5-month-old hybrid is shown. (E) Protein structure of MFRP and predicted structure of mutant MFRP alleles. TM, transmembrane domain; CUB, CUB domain; L, LDLR domain; FZD, Frizzled domain; NS, nonsense.

Misregulation of Mfrp and Ctrp5 Expression in Mfrp174delG and rd6 Mice

Given that Mfrp174delG causes a frame shift and premature stop codon in the third of 14 predicted exons in the Mfrp transcript, we hypothesized that the mutant transcript would be a substrate for nonsense-mediated decay. In this mechanism, protein complexes at exon junctions in mature mRNAs that are not displaced by ribosomes during translation, such as those sufficiently downstream of a premature stop codon, target the mRNA for degradation.22 However, quantitative RT-PCR using primers targeted against Mfrp showed that it is not downregulated and is, in fact, significantly upregulated in rd6 eyecups. In addition, Ctrp5 primers showed significant upregulation of that transcript in both mutants (Fig. 5A). This may indicate the presence of an autoregulatory feedback mechanism that controls the expression of these two genes. At the protein level, the ∼120-kDa MFRP-specific band in wild-type animals was not detectable in Mfrp174delG mice, similar to what has been shown previously for rd6.14 CTRP5 has a predicted molecular weight of 26 kDa, and its abundance, although variable, was generally upregulated in Mfrp174delG animals (Figs. 5B, 5C).

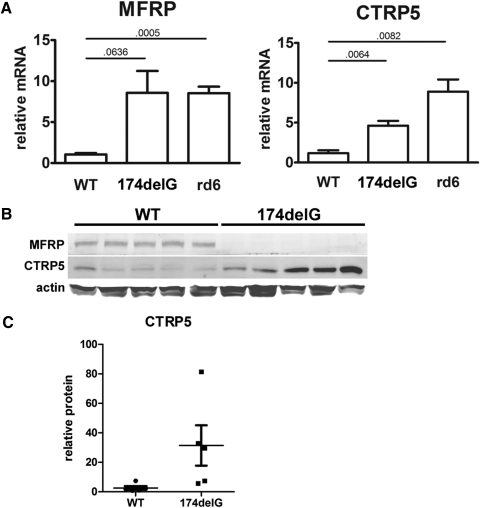

Figure 5.

(A) Quantitative RT-PCR from mouse eyecups shows upregulation of both Mfrp and Ctrp5 mRNA in mutant mice. (horizontal bars) P values from pairwise t-tests. (B) Immunoblots showing expression of MFRP and CTRP5 in whole eyecups. MFRP is not detectable above background in Mfrp174delG mice, and CTRP5 is variable but generally upregulated compared with controls. (C) CTRP5 protein expression is quantitated.

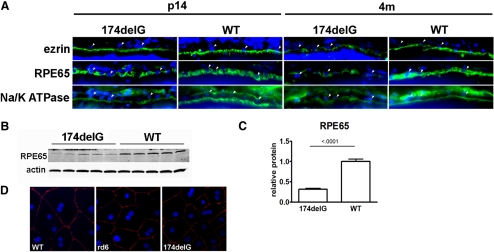

Markers of the Apical RPE Domain Are Appropriately Polarized in Mfrp174delG Mice

Given that we observed degeneration of the RPE in Mfrp174delG animals and that MFRP is expressed on the apical surface of the RPE,7 we sought to determine whether two other markers of the RPE apical surface were appropriately polarized. At both postnatal day (P) 14 and 4 months of age, the apical subcellular distributions of Na/K ATPase and ezrin in the RPE were similar in control and Mfrp174delG mice (Fig. 6A). However, apical staining was reduced and less continuous in Mfrp174delG at 4 months. In addition, immunostaining of cytoplasmic RPE65 showed less homogeneous distribution of this protein in mutant RPE, and we confirmed that RPE65 is downregulated by Western blot analysis of 7-week-old mice (Figs. 6B, 6C). This might have been due to a randomly assorting RPE65 polymorphism (L450M) that was introduced into the colony from C57Bl/6 that decreases the half-life of the protein.23 Finally, ZO-1, a marker of tight junctions, was localized to the cell periphery in primary mutant RPE explants in a manner indistinguishable from that of wild-type controls (Fig. 6D). We therefore conclude that intact RPE of Mfrp174delG animals, before the onset of retinal degeneration and RPE atrophy, is appropriately polarized.

Figure 6.

(A) Cryosections of eyes from wild-type and Mfrp174delG mice were stained with antibodies against ezrin, Na/K ATPase, and RPE65 (green). (arrowheads) Examples of RPE nuclei (blue). Images are oriented such that the apical domain of the RPE is below the RPE nuclei. Na/K ATPase staining basal to RPE nuclei is from choroidal cells. Images are scaled so that staining intensity is roughly equivalent and protein localization can be easily compared, and they are not quantitative. (B, C) Western blot analysis demonstrated significant downregulation of RPE65 in 7-week-old Mfrp174delG mice. This was likely due to random assortment of an RPE65 polymorphism that decreased the stability of the protein. (D) ZO-1 staining of primary RPE explants. ZO-1 (red) was properly localized to the cell periphery in both control and mutant explants.

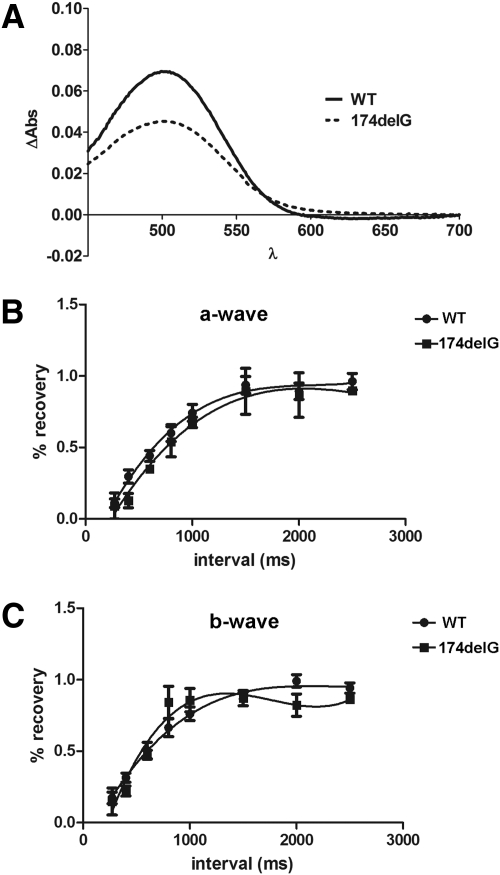

Paired-Flash ERG Suggests Normal Retinoid Cycling in Mfrp174delG Mice

Because most successfully mapped mutations causing recessive flecked retina diseases in humans have been linked to proteins in the visual cycle,24,25 we sought to determine whether Mfrp174delG mice showed any signs of impaired retinoid cycling. First, we used difference spectroscopy to compare the amount of unbleached rhodopsin in extracts of dark-adapted retinas from Mfrp174delG and control mice at 3 weeks. We found a significant decrease in the absorption curve of Mfrp174delG mice (P < 0.0001, ANOVA; Fig. 7A), but this correlated with the observation that outer segments in 3-week-old Mfrp174delG mice were nearly 30% shorter than those of wild-type controls (wild-type, 18.2 ± 0.87 μm; Mfrp174delG, 13.1 ± 0.95 μm), suggesting that decreased rhodopsin was attributed to short and disorganized outer segments. To further evaluate retinoid cycling in vivo, we used a paired-flash paradigm to measure ERG recovery after desensitization in P14 animals. At this early stage, the maximal a- and b-wave amplitudes of mutant animals were not significantly different from those of controls. We found no significant difference in ERG recovery after a desensitizing flash between wild-type and Mfrp174delG mice, suggesting that retinoid cycling is intact (Figs. 7B, 7C).

Figure 7.

(A) Difference spectroscopy was used to compare the amount of unbleached rhodopsin in dark-adapted retinal extracts from weanling wild-type and Mfrp174delG mice. (B, C) Paired flash ERG recordings measure a- and b-wave recovery as a function of time after a desensitizing flash. Recovery of wild-type and Mfrp174delG responses increased in parallel as the interval between the two flashes was lengthened.

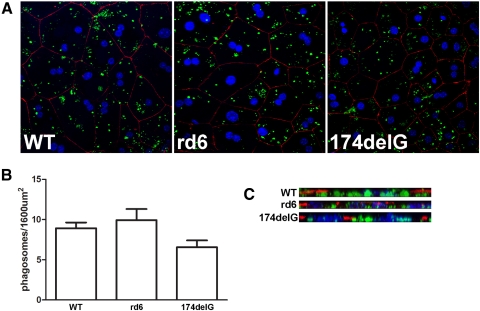

In Vitro Assays Indicate That RPE Phagocytosis Is Normal in rd6 and Mfrp174delG Mice

It has been reported that RPE from 2-month-old rd6 animals fails to internalize significant numbers of opsin-positive phagosomes after acute high-intensity light stimulation.14 However, we were curious whether the reported result could have been caused by reduced shedding after stimulation, given our observation of significant outer segment shortening and disorganization by weaning age. To approach this problem, we performed in vitro phagocytosis assays on primary RPE cultures from wild-type, rd6, and Mfrp174delG animals. We did not detect any significant differences in phagosome counts in confluent fields among these cultures (Figs. 8A, 8B). To confirm that the OS particles provided to the cultures were normally internalized, we evaluated 3D reconstructions of confocal z-series and observed that the vast majority of all observable FITC-positive material was basal to the zonular band of ZO-1 staining in all cases (Fig. 8C). We therefore conclude that RPE cells from both rd6 and Mfrp174delG animals are fully capable of internalizing isolated outer segment material in culture.

Figure 8.

In vitro phagocytosis assays were conducted to evaluate the overall capacity of mutant RPE cells to internalize OS particles. (A) Representative images showing primary RPE cultures after 2-hour incubation with FITC-labeled purified outer segments (green). Cells are immunolabeled for ZO-1 (red) to indicate cell junctions and stained with TO-PRO3 to label nuclei (blue). (B) Averaged results from four to six fields are shown and are not significantly different (P = 0.079, ANOVA). (C) X-projections were constructed from the confocal stacks to verify that the observed OS particles were internalized and basal to the ZO-1 staining.

Increased Numbers of Apical Microvilli in rd6 and Mfrp174delG RPE

During routine retina dissections with mutant mice, we noted a strong tendency for large amounts of pigmented material to stick to the posterior retina. This led us to the hypothesis that the interface between the RPE and the retina was altered in mutant animals. We found that it was difficult to thoroughly evaluate the structure of RPE microvilli while the retina remained attached because they are typically so compressed within the subretinal space. Therefore, we enzymatically weakened the interaction between the two layers by treatment with hyaluronidase, followed by physical removal of the retina and preparation of the remaining tissue for electron microscopy. By this method, the microvilli are easier to evaluate because they project nearly perpendicularly to the apical membrane and are more effectively fixed. We observed a remarkable increase in microvillar number in both Mfrp174delG and rd6 mice compared with controls (Fig. 9), which could be related to the increased adhesion between the retina and the RPE. Furthermore, we frequently observed large cytoplasmic inclusions in Mfrp174delG RPE. These structures were never observed in control mice, and, though we did not note their presence in rd6 mice either, an earlier study did comment on similar structures.3 The inclusions contain numerous small, circular, membranous structures similar to those seen in the subretinal macrophages (compare to Fig. 3D). These structures may be lipid-rich deposits that are partially extracted during processing. Melanin granules were always present in these deposits, and there was no visible membrane delimiting the entire structure. We similarly evaluated choroid plexus, a tissue similar to the RPE in embryological origin and with significant functional parallels, but found no observable differences between control and mutant animals (data not shown).

Figure 9.

(A) Representative electron microscopic images of midperipheral RPE from control and mutant animals. Neural retina was removed in these samples to facilitate imaging of RPE microvilli. Note the presence of a large cytoplasmic inclusion in the 174delG image (arrow). Scale bar, 2 μm. (B) The average microvillus densities of three biological replicates per group are displayed (P = 0.001, ANOVA).

Discussion

We have identified a novel mutation in the mouse that results in slow photoreceptor degeneration. These animals have abnormal scotopic ERGs by weaning age but have photopic responses that are preserved for several months, suggesting that the disease initially affects rods. We mapped this mutation to a locus on chromosome 9 that included two candidate genes. Sequencing of these genes revealed a deletion in exon 3 of Mfrp that is predicted to result in premature truncation and loss of the majority of the protein, including the entire membrane and extracellular domains. We have designated this mutation Mfrp174delG.

The rd6 mouse, which has a similar phenotype because of a splicing mutation in Mfrp, has been described previously.2,3 Although Mfrp174delG and rd6 mice have significant similarities, there are two notable differences that deserve attention. First, the overall progression of photoreceptor loss was more rapid in Mfrp174delG mice than what was reported for rd6. In rd6 mice, the ONL was reported to be approximately 4 nuclei thick at 11 months.3 In Mfrp174delG mice, the ONL was reduced to approximately two nuclei as early as 7 months. Second, though there was no report of RPE atrophy in the rd6 mouse, even in 29-month-old animals, we observed significant loss of RPE cells by 21 months in Mfrp174delG mice. We emphasize this difference by noting that careful analysis of a 36-month-old rd6 mouse, in which some RPE disorganization and hypertrophy were observed, revealed no RPE atrophy (data not shown). The loss of RPE cells in Mfrp174delG correlates well with reports of choroidal transmission hyperfluorescence and pigment clumping in humans with mutations in MFRP.5 Importantly, this initial characterization of Mfrp174delG mice was made on a hybrid genetic background in which the Rpe65 L450M polymorphism was randomly assorting, whereas rd6 mice are congenic. Efforts to move the Mfrp174delG mutation onto a C57Bl/6J background to allow more direct comparisons with rd6 are ongoing. Because we have shown that both Mfrp174delG and rd6 transcripts are present, it is possible that a trace amount of mutant protein is produced in both cases. In the case of rd6, the predicted protein contains the antibody binding epitope but may be below the level of detection. The predicted Mfrp174delG protein lacks this domain (see Fig. 4E). Either of these mutant proteins, even at trace levels, could confer distinct effects that lead to subtle differences in phenotype.

A characteristic that is completely penetrant among multiple human families with MFRP mutations is the presence of nanophthalmia.4–6,26 This phenotype is notably absent from both rd6 and Mfrp174delG mice. It has been suggested that an Mfrp knockout would be useful to rule out possible residual function of the rd6 allele, which could conceivably account for this difference.27 The Mfrp174delG allele, if translated, is predicted to lack all functional domains of the protein. This is similar to the nanophthalmia-causing human Q175X mutation, which is truncated within the first CUB domain.4 Thus, the Mfrp174delG mutation does not explain the discrepancy between human and mouse phenotypes and raises the possibility of divergence in the function of MFRP between these two species.

Our overarching goal was to determine the molecular function of MFRP with regard to the RPE and to describe precisely why it is critical for proper development and maintenance of the adjacent photoreceptors. To this end, we evaluated several candidate mechanisms. First, given that all flecked-retina diseases in humans are ultimately caused by mutations in proteins critical to retinoid cycling,24,25 we analyzed this pathway by two independent methods. We found that rhodopsin in its unbleached state, the end product of the retinoid cycle, is present in proper proportion to the amount of outer segment membrane that remains in mutant animals. Furthermore, we did not note any differences in ERG recovery after desensitization. Taken together, the results of these two experiments suggest that MFRP is not required for proper recycling of retinoid pigments. Second, we reevaluated the hypothesis that MFRP is required for RPE phagocytosis, which was recently tested by Won et al.14 The in vivo approach used in that study measured the number of rhodopsin-containing RPE phagosomes after extraordinarily bright light stimulation in rd6 and control mice. However, the 2-month-old animals used in that experiment already had significant outer segment degeneration, raising the possibility that the observed decrease in phagocytosis could have resulted from the decreased availability of outer segment material. To address this, we used an in vitro model of RPE phagocytosis and found that neither rd6 nor Mfrp174delG RPE cells were deficient in their ability to phagocytose purified labeled outer segment fragments.

We have also observed significant structural changes in the apical domain of the RPE in both rd6 and Mfrp174delG mice. Both mutants had significantly increased numbers of RPE microvilli, which we believe leads to alterations in the interface and adhesive properties between RPE and photoreceptors. We estimated the microvilli to be of normal length, which is in contrast to that reported previously for rd6.14 However, we believe that the preparation used in the present study, in which the neural retina is removed to allow for more efficient fixation and observation of RPE microvilli, provides a more accurate picture of these structures. Immunoelectron microscopy studies previously localized MFRP to the apical RPE membrane, but not within the microvilli themselves.7 Thus, we speculate that MFRP may play a role in regulating microvillar genesis in the RPE or that it may interact with other proteins in the cortical cytoskeleton that are involved in microvillus anchoring or stability. One would expect that such a drastic upregulation of microvilli would require a concomitant increase in ezrin, a protein that is thought to be a critical structural element of microvilli. However, our immunohistochemical analysis of ezrin expression in Mfrp174delG mice, though not quantitative, does not indicate an increase in ezrin. The only protein known to interact directly with MFRP is CTRP5, a secreted, short-chain collagen containing a C-terminal c1q globular domain. CTRP5 is secreted from the RPE and binds the extracellular CUB domain of MFRP on the apical RPE membrane.7,9 CTRP5 is misregulated in mutant animals, but we propose that this is not directly related to the loss of MFRP. CTRP5 was shown to be upregulated in mitochondrially depleted L6 cells,12 where it stimulated AMPK activation. Although we did not observe any obvious changes in number or localization of mitochondria in mutant RPE, it is possible that a degree of sublethal stress occurred and that CTRP5 upregulation was in response to this.

The observation that the Mfrp174delG mouse develops atrophic regions of RPE suggests its usefulness as a model for geographic atrophy, a type of advanced-stage age-related macular degeneration. Although certain palliative measures are available to treat hemorrhagic AMD, a secondary condition in which choroidal blood vessels protrude through the RPE in response to diffusion barriers along Bruch's membrane, no treatment is available for geographic atrophy. We therefore propose that Mfrp174delG mice present a unique model in which to study not only the role of MFRP in the RPE but also the pathogenesis of atrophic macular degeneration in general. Furthermore, this model will be useful to test various pharmacologic agents that may come under development for the treatment of patients with this disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Weaver (University of Massachusetts Medical School) for providing the Per3−/− mutant mice used to establish the colony and for assistance in performing preliminary studies, Clive Wells for excellent technical assistance with electron microscopy, Joseph Takahashi for discussions about gene mapping using SNPs, Silvia Finnemann for assistance with phagocytosis assays, and D. J. Sidjanin for assistance with interpretation of gene-mapping data.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY02414 (JCB) and EY03222 (JCB) and Training Grant T32EY014537 (JF) and by National Eye Institute Core Grant P30EY01931.

Disclosure: J. Fogerty, None; J.C. Besharse, None

References

- 1. Katoh M. Molecular cloning and characterization of MFRP, a novel gene encoding a membrane-type Frizzled-related protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:116–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kameya S, Hawes NL, Chang B, Heckenlively JR, Naggert JK, Nishina PM. Mfrp, a gene encoding a frizzled related protein, is mutated in the mouse retinal degeneration 6. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1879–1886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hawes NL, Chang B, Hageman GS, et al. Retinal degeneration 6 (rd6): a new mouse model for human retinitis punctata albescens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:3149–3157 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sundin OH, Leppert GS, Silva ED, et al. Extreme hyperopia is the result of null mutations in MFRP, which encodes a Frizzled-related protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9553–9558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ayala-Ramirez R, Graue-Wiechers F, Robredo V, Amato-Almanza M, Horta-Diez I, Zenteno JC. A new autosomal recessive syndrome consisting of posterior microphthalmos, retinitis pigmentosa, foveoschisis, and optic disc drusen is caused by a MFRP gene mutation. Mol Vis. 2006;12:1483–1489 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crespi J, Buil JA, Bassaganyas F, et al. A novel mutation confirms MFRP as the gene causing the syndrome of nanophthalmos-retinitis pigmentosa-foveoschisis-optic disk drusen. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:323–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mandal MN, Vasireddy V, Jablonski MM, et al. Spatial and temporal expression of MFRP and its interaction with CTRP5. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:5514–5521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hopkins DR, Keles S, Greenspan DS. The bone morphogenetic protein 1/Tolloid-like metalloproteinases. Matrix Biol. 2007;26:508–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shu X, Tulloch B, Lennon A, et al. Disease mechanisms in late-onset retinal macular degeneration associated with mutation in C1QTNF5. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1680–1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ayyagari R, Mandal MN, Karoukis AJ, et al. Late-onset macular degeneration and long anterior lens zonules result from a CTRP5 gene mutation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3363–3371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wong GW, Krawczyk SA, Kitidis-Mitrokostas C, Revett T, Gimeno R, Lodish HF. Molecular, biochemical and functional characterizations of C1q/TNF family members: adipose-tissue-selective expression patterns, regulation by PPAR-gamma agonist, cysteine-mediated oligomerizations, combinatorial associations and metabolic functions. Biochem J. 2008;416:161–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Park SY, Choi JH, Ryu HS, et al. C1q tumor necrosis factor alpha-related protein isoform 5 is increased in mitochondrial DNA-depleted myocytes and activates AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27780–27789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim MJ, Lee W, Park EJ, Park SY. Role of hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha in transcriptional regulation of C1qTNF-related protein 5 in the liver. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:3080–3084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Won J, Smith RS, Peachey NS, et al. Membrane frizzled-related protein is necessary for the normal development and maintenance of photoreceptor outer segments. Vis Neurosci. 2008;25:563–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim TS, Maeda A, Maeda T, et al. Delayed dark adaptation in 11-cis-retinol dehydrogenase-deficient mice: a role of RDH11 in visual processes in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8694–8704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sokolov M, Lyubarsky AL, Strissel KJ, et al. Massive light-driven translocation of transducin between the two major compartments of rod cells: a novel mechanism of light adaptation. Neuron. 2002;34:95–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moran JL, Bolton AD, Tran PV, et al. Utilization of a whole genome SNP panel for efficient genetic mapping in the mouse. Genome Res. 2006;16:436–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nandrot EF, Kim Y, Brodie SE, Huang X, Sheppard D, Finnemann SC. Loss of synchronized retinal phagocytosis and age-related blindness in mice lacking alphavbeta5 integrin. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1539–1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shearman LP, Jin X, Lee C, Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Targeted disruption of the mPer3 gene: subtle effects on circadian clock function. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6269–6275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chavali VR, Khan NW, Cukras CA, Bartsch DU, Jablonski MM, Ayyagari R. A CTRP5 gene S163R mutation knock-in mouse model for late-onset retinal degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:2000–2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rebbapragada I, Lykke-Andersen J. Execution of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: what defines a substrate? Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:394–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wenzel A, Reme CE, Williams TP, Hafezi F, Grimm C. The Rpe65 Leu450Met variation increases retinal resistance against light-induced degeneration by slowing rhodopsin regeneration. J Neurosci. 2001;21:53–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hayashi T, Goto-Omoto S, Takeuchi T, Gekka T, Ueoka Y, Kitahara K. Compound heterozygous RDH5 mutations in familial fleck retina with night blindness. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84:254–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Humbert G, Delettre C, Senechal A, et al. Homozygous deletion related to Alu repeats in RLBP1 causes retinitis punctata albescens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4719–4724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mukhopadhyay R, Sergouniotis PI, Mackay DS, et al. A detailed phenotypic assessment of individuals affected by MFRP-related oculopathy. Mol Vis. 2010;16:540–548 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sundin OH. The mouse's eye and Mfrp: not quite human. Ophthalmic Genet. 2005;26:153–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]