Abstract

Patients with Hodgkin lymphoma are usually cured by primary therapy using chemotherapy alone or combined modality therapy with external beam radiation. Patients who do not experience a complete remission or those who experience relapse may by salvaged by high-dose therapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (ASCT). Success of this approach is largely dependent on the tumor being sensitive to salvage chemotherapy before transplant. More studies are showing the predictive value of functional imaging in this setting. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has greater risk of nonrelapse mortality and is generally reserved for patients who experience relapse post-ASCT, but may provide long-term survival for some patients through graft-versus-tumor immune effects.

Keywords: Hodgkin lymphoma, autologous, allogeneic, transplantation

Treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) has improved so that most patients, even those with high-risk disease, are now cured with primary therapy.1,2 However, for patients with primary refractory disease, or those experiencing relapse after complete remission, the disease may become life-threatening. For many patients, the current standard of care involves salvage chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (ASCT). Successful outcome depends on chemosensitivity at the time of ASCT, the high-dose conditioning regimen to eradicate the disease, and the stem cell collection being tumor-free. Marrow involvement in HL is less common than in non–Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL); however, because of the difficulty in detecting tumor cells in peripheral blood stem cell grafts using current methods (flow cytometry), how often tumor cells collected for ASCT actually contribute to relapse is unclear. Pretransplant-negative FDG-PET imaging provides powerful predictive information on the success of ASCT.3

Management of patients who experience relapse after ASCT is often palliative. Patients who receive a second high-dose conditioning regimen and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (alloHCT) have shown high nonrelapse mortality (NRM). The development of reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens for use before alloHCT has led to increased use of this modality for these patients or those with medical contraindications to high-dose therapy.

This article reviews the current status of the use of ASCT and alloHCT for the management of HL.

ASCT

The current generally accepted use of high-dose therapy and ASCT is for salvage therapy of patients with relapsed or primary refractory HL previously treated with chemotherapy or combined modality therapy. Patients experiencing very limited-stage relapse, or late relapse after irradiation only, may have lower-risk disease and be managed with non-ASCT treatments, but this discussion is beyond the scope of this article. Selective recent trials of ASCT are detailed in Table 1. More controversial is its use as consolidation of primary therapy in high-risk patients or in patients with refractory disease. Few results from prospective randomized clinical trials adequately address these issues, and most studies have not included functional imaging. In addition, no unified acceptance of prognostic HL risk factors exists for comparing outcomes.

Table 1.

Results of Autologous Stem Cell Transplant in Hodgkin Lymphoma: Transplant Versus Nontransplant

| Study | No. Patients | Regimen | EFS/DFS/FFS | Overall Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newly Diagnosed, Randomized Prospective Trial | ||||

| Federico et al.18 | 163 | 5 y | ||

| 4 CHT-CR/PR | ASCT, 75% | 88% | ||

| ASCT vs. 4 CHT | CHT, 82% | 88% | ||

| P = .4 | P = .99 | |||

| Newly Diagnosed, Retrospective Trial | ||||

| Vigouroux et al.17 | 150 | Various | 5 y | |

| ASCT, 81% | 85% | |||

| CTP, 51% | 71% | |||

| P = .0004 | P = .06 | |||

| Relapsed Disease, Prospective Trials | ||||

| Schmitz et al.4 | 144 | Dexa-BEAM × 2/BEAM ASCT vs. Dexa-BEAM × 4 | 3 y | |

| ASCT, 55% | 80% | |||

| CHT, 34% | 70% | |||

| P = .019 | P = .06 | |||

| Linch et al.6 | 40 | BEAM | 3 y | |

| ASCT, 53% | ||||

| P = .025 for ASCT | ||||

Abbreviations: ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; BEAM, carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan; CHT, standard chemotherapy; CTP, combined conventional therapy; DFS, disease-free survival; EFS, event-free survival; FFS, failure-free survival.

ASCT for Relapsed HL

For patients with relapsed or refractory HL, prospective randomized trials have shown the benefit of ASCT compared with conventional salvage therapy. A study from the German Lymphoma Working Group evaluated ASCT compared with nontransplant therapy for refractory or relapsed HL after conventional therapy.4 In this study, the event-free survival was better with ASCT (55% vs. 34%; P = .019) and overall survival was borderline improved at 80% versus 70% (P = .06). However, overall survival was confounded by the fact that 46% of the patients who experienced relapse after the salvage Dexa-Beam therapy proceeded to subsequent ASCT. An updated analysis showed that the 7-year event-free survival rate after ASCT was 49%.5

A smaller prospective randomized trial in 40 patients showed a 3-year event-free survival rate of 53% (P = .025) for carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan (BEAM) plus ASCT versus 10% for miniBEAM chemotherapy.6 Overall survival was similar, again because of crossover to ASCT after relapse. Both of these studies showed that ASCT in first relapse provided superior event-free survival, especially for those who experienced relapse after a short duration of initial complete remission. Because of these results, further accrual to transplant versus nontransplant trials is difficult and ASCT has become the preferred treatment for patients with chemotherapy-sensitive, relapsed, or primary refractory HL who are medically fit.

In general, data from single-center series and registry data have shown that 40% to 50% of patients with relapsed or refractory HD are alive 5 years after ASCT. Data from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) show that better outcome is observed for patients with less disease burden at the time of ASCT. Patients experiencing complete remission at the time of ASCT fare better than those with chemosensitive disease but who have less than a complete remission.7 Table 2 summarizes selected studies published in the past decade.

Table 2.

Selected Trials of Autologous Stem Cell Transplant for Relapsed/Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma

| Study | No. Patients | Regimen | EFS/DFS/FFS (%) | OS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sirohi et al.9 | 195 | MBE/ME | 5-y: 44; 10-y: 37 | 5-y: 55; 10-y: 49 |

| PR: 44; NR: 14 | PR: 59; NR: 17 | |||

| Stiff et al.43 | 81 | E, Cy, TBI | 5-y: 41 | 5-y: 54 |

| Sureda et al.8 | 357 | Various | 5-y: 49 | 5-y: 57 |

| Tarella et al.44 | 102 | Mitx/Must | 5-y: 53; CR: 78 | 5-y: 64; CR: 88 |

| PR: 41; NR: 7 | PR: 58; NR: 13 | |||

| Wadehra et al.45 | 127 | BuCyE | 5-y: 48 | 5-y: 51 |

| Czyz et al.46 | 341 | Various | 5-y: 45; CS: 62 | 5-y: 64; CS: 79 |

| Res: 46 | CR: 77; PR: 71; | |||

| < PR: 33 | ||||

| Engelhardt et al.47 | 115 | Various | 5-y: 46 | 5-y: 58 |

| Lavoie et al.48 | 100 | Various | 15-y: 54 | |

| First relapse: 67 | ||||

| Primref: 39 | ||||

| Adv: 29 |

Abbreviations: Adv, advanced disease; B, carmustine; Bu, busulfan; CR, complete remission; CS, chemosensitive; Cy, cyclophosphamide; DFS, disease-free survival; E, etoposide; EFS, event-free survival; FFS, failure-free survival; M, melphalan; Mitx, mitoxantrone; Must, mustard; NR, no response; OS, overall survival; PR, partial remission; Primref, primary refractory; Res, resistant disease; TBI, total body irradiation.

Prognostic Factors for ASCT

Prognostic factors affecting outcome after ASCT have been evaluated in multiple trials. Among 357 patients in first relapse, the most important factors that adversely influenced the time to treatment failure were advanced stage at diagnosis, radiotherapy before ASCT, short interval of first complete remission, and detectable disease at ASCT. In addition, the year of transplant, bulky disease at diagnosis, a short time to relapse from initial therapy, detectable disease at ASCT, or one or more extranodal areas at ASCT adversely affected overall survival.8

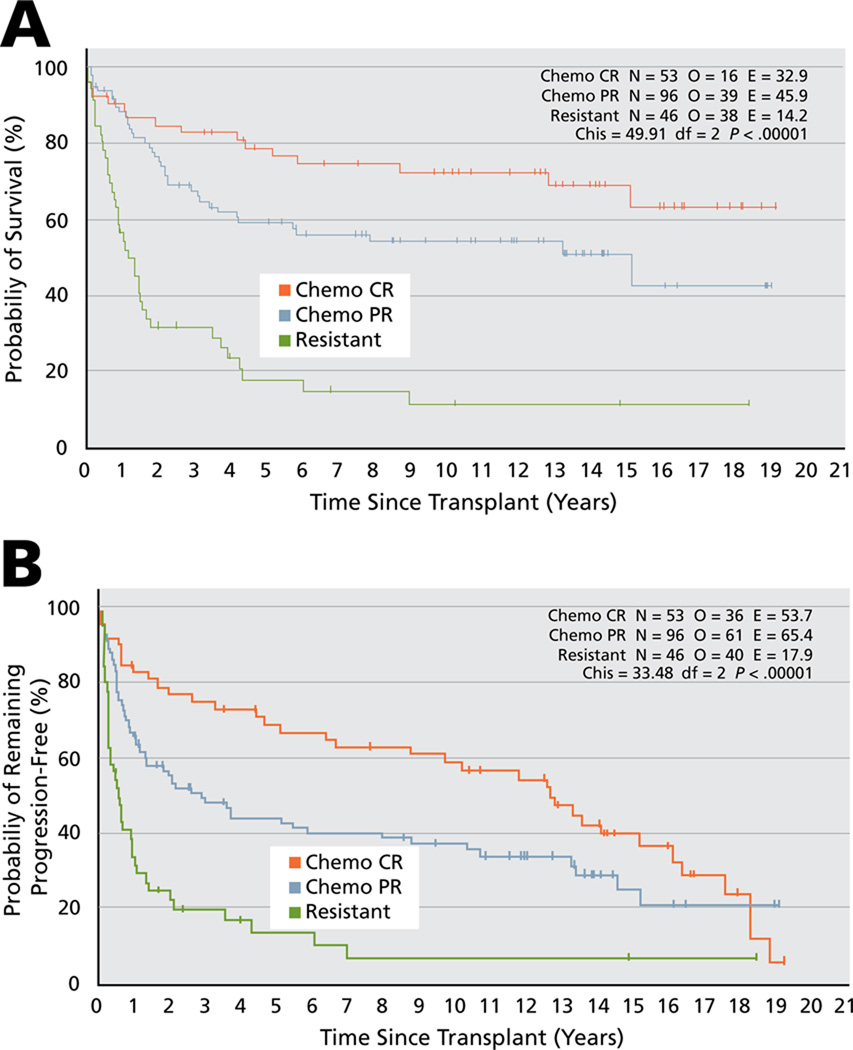

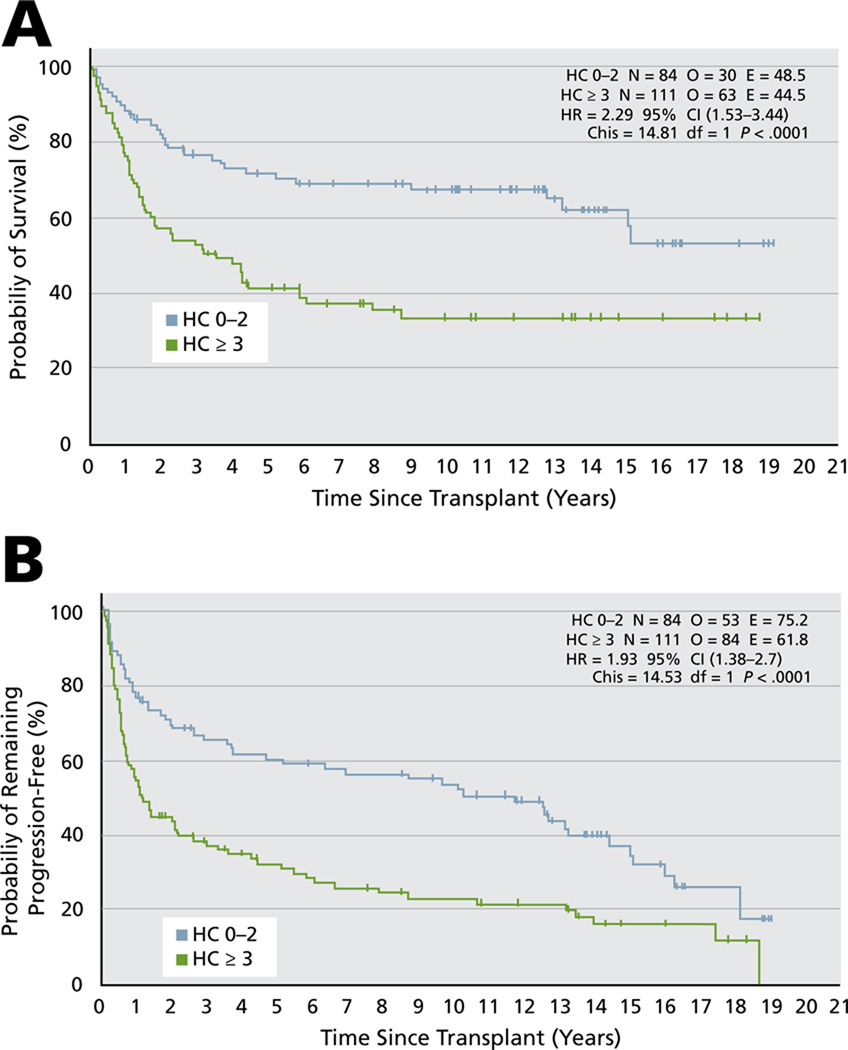

Sirohi et al.9 reported on long-term outcome of relapsed and refractory HD at their center after ASCT. For the entire group of patients, the 5-year progression-free and overall survival rates were 44% and 54%, and 10-year progression-free and overall survival rates were 37% and 49.4%, respectively. The 5-year overall survival rates were 79% for patients experiencing complete remission at the time of ASCT, 59% for those experiencing a partial response, and only 17% for those with resistant disease (P < .0001). The 10-year results were 72%, 54%, and 11%, respectively (see Table 2 and Figure 1). Use of the 7-factor HL prognostic index (Hasenclever index [HI]10 consisting of albumin < 4 g/dL; hemoglobin < 10.5 g/dL; male sex; stage IV disease; age ≥ 45 years; WBC count ≥ 15000/mm3; and lymphocyte count < 600 /mm3 or < 8% WBC count) at the time of ASCT was also predictive. Five-year overall survival rates for an HI score of 0 to 2 were 71% versus 41.5% for those with an HI score of 3 or greater (hazard ratio [HR], 2.29; 95% CI, 1.53–3.44; P = .0001), and the 10-year overall survival rates were 67% and 34%, respectively. The 5-year progression-free survival rate of patients with an HI score of 0 to 2 was 60% versus 32% for those with an HI score of 3 or greater (HR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.38–2.7; P = .0001; Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The effect of chemosensitive disease at time of autologous stem cell transplant on overall (A) and progression-free survival (B) of relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Abbreviations: Chemo, chemotherapy; CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission.

From Sirohi B, Cunningham D, Powles R, et al. Long-term outcome of autologous stem-cell transplantation in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Oncol 2008;19:1312–1319; by permission of Oxford University Press.

Figure 2.

The effect of Hasenclever index at time of autologous stem cell transplant on overall (A) and progression-free survival (B) of relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. From Sirohi B, Cunningham D, Powles R, et al. Long-term outcome of autologous stem-cell transplantation in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Oncol 2008;19:1312–1319; by permission of Oxford University Press.

Nearly all studies have shown the importance of chemotherapy sensitivity on the outcome of ASCT. However, ASCT may also benefit patients in whom standard chemotherapy is not effective. Multiple trials have shown prolonged overall and progression-free survivals in a minority of patients.11–13 The authors’ group in Seattle has reported on the outcome of 64 patients with chemotherapy-resistant disease at the time of ASCT.14 Twenty-six patients (41%) underwent total body irradiation (TBI)–based conditioning. The estimated 5-year overall and progression-free survivals were 31% and 17%, respectively. Multivariate analysis only identified year of transplant as independently associated with improved overall (P = .008) and event-free survivals (P = .04). The event-free survival rate was 31% for patients undergoing transplant between 2000 and 2005.

Biologic markers of disease are also beginning to be evaluated. Recently, Persky et al.15 screened for the expression of bcl-2, Bax, Bim, p53, and interleukin (IL)-6. Bim expression was associated with inferior overall survival (P = .0385). Although p53 and bcl-2 expression has been reported to predict worse prognosis at initial treatment, ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide) salvage therapy and ASCT seem to overcome the prognostic value of these markers. A 3-factor model consisting of B symptoms at relapse, extranodal disease, and complete remission duration of less than 1 year best predicted outcome. When comparing the number of factors in the model (0/1 vs. 2/3) for event-free survival (8.6 vs. 1 year; P = .0008) and overall survival (9.3 vs. 3.8 years; P = .0001), the difference in outcome was significantly worse for patients with 2 or 3 factors.

In primary progressive HD, the German Hodgkin Study Group reported that Karnofsky performance score at time of progression (P < .0001), age older than 50 years (P = .019), and failure to experience a temporary remission on front-line therapy (P = .0003) adversely affected survival despite whether patients underwent ASCT.16 Patients with none of these risks factors had a 5-year overall survival of 55% versus 0% for those with 3 prognostic factors. For all patients, the 5-year freedom from second failure and overall survival were 17% and 26%, respectively, versus 31% and 43% for patients who received ASCT. However, in this prospective study of 206 patients, only 70 (34%) received ASCT.

ASCT as Primary Therapy for High-Risk HL

Given the observation that ASCT can be used as salvage therapy in patients with relapsed HL, it was logical to evaluate it in the initial therapy of patients with advanced unfavorable prognostic factors in whom conventional therapy has a lower chance of cure. The difficulty of this approach has been in identifying patients with a high enough probability of failure on conventional therapy to justify treating all patients with ASCT. This is further complicated by the increasing success of aggressive chemotherapy combinations, such as escalated BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone),2 and on the greater use of functional imaging to confirm complete remission in patients with residual masses.

Results of retrospective studies comparing the outcomes of high-risk patients after treatment with conventional therapy alone versus conventional therapy and ASCT suggested an improved outcome with ASCT.17 High-risk patients (mediastinal mass ≥ 45% of thoracic diameter, stage IV disease, or a incomplete response to initial frontline chemotherapy) had a better 5-year freedom from progression rate compared with conventional therapy alone (87% vs. 55%, respectively; P = .0004); however, the overall survival rate was not different (85% for ASCT vs. 71% for conventional therapy; P = .06). ASCT was superior in patients with greater than 50% tumor reduction (freedom from progression, 91% for ASCT vs. 65% for combined modality, and overall survival, 92% vs. 77%, respectively [P = .02]) and for the group with less than a 50% response to initial therapy (freedom from progression, 80% for ASCT vs. 22% for combined modality [P = .0003], and overall survival, 76% vs. 46%, respectively [P = .04]).

However, a prospective study randomized 163 patients with 2 or more risk factors (elevated lactate dehydrogenase, bulky mediastinal mass, more than 1 extranodal site, low hematocrit, or inguinal involvement), who were experiencing complete remission or partial response after 4 cycles of standard therapy, to either an additional 4 cycles of standard therapy or ASCT.18 At 48-months follow-up, the overall survival and rates of relapse and disease-free survival were not statistically different.

Thus, few data currently support the use of ASCT in patients who are in first complete remission. However, patients with persistent disease (partial response or functional imaging positive) at the completion of standard therapy should be considered for biopsy, salvage therapy, and ASCT.

Role of Salvage Second ASCT

For selected patients who have experienced relapse after ASCT, a second high-dose treatment may be considered. Patients treated have been highly selected, and those who experienced greater than 1 year of remission with the first ASCT, who have chemosensitive disease, and who can be debulked with standard salvage therapy seem to have benefited most from this approach.19 Whether a second ASCT is preferable to other approaches, including alloHCT, is unknown.

Functional Imaging

Sensitivity to chemotherapy has emerged as a critical factor in predicting outcome after ASCT. However, many patients have residual masses after salvage chemotherapy. Functional imaging with FDG-PET (previously with gallium scans) provides important prognostic information.

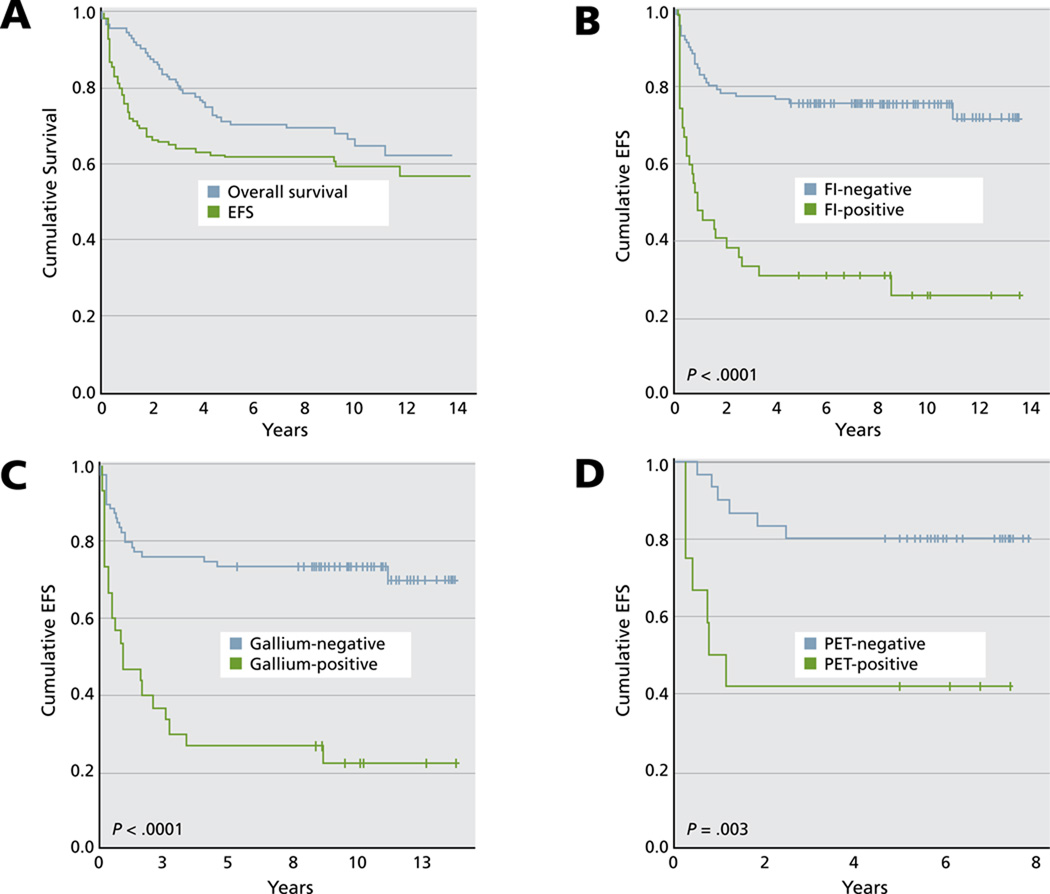

Moskowitz et al.3 reported on the outcome of patients with relapsed HL who had chemosensitive disease after ICE salvage therapy and were undergoing ASCT. Patients with positive functional imaging (gallium or FDG-PET) at the time of transplant conditioning had a 5-year event-free survival rate of 31%, compared with 75% for those with negative functional imaging (Figure 3). The administration of involved-field radiotherapy with ASCT marginally improved event-free survival rates (P = .055).

Figure 3.

Patient outcome. (A) Overall survival and event-free survival (EFS). (B) EFS according to functional imaging (FI) status before autologous stem cell transplant. (C) EFS according to FI status for patients evaluated by gallium. (D) EFS according to FI status for patients evaluated by FDG-PET.

From Moskowitz AJ, Yahalom J, Kewalramani T, et al. Pretransplantation functional imaging predicts outcome following autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2010;116:4936. Blood: journal of the American Society of Hematology by American Society of Hematology. © 2009 Reproduced with permission of American Society of Hematology (ASH).

Moskowitz et al.20 also combined their 3-factor model (presence of extranodal disease, duration of initial response < 1 year, and B symptoms) with functional imaging. Outcome was best in patients with chemosensitive disease who were gallium/FDG-PET– negative with good prognostic factors versus those who were gallium/FDG-PET–positive who had all risk factors. These data suggest that a negative FDG-PET scan is associated with the best outcome after ASCT.

ASCT and Secondary Malignancies

In the Sirohi et al.9 study of 195 patients with HL who received ASCT (with non–TBI conditioning) between 1985 and 2005, 10% developed secondary cancers, of which 7 of 20 cases were therapy-induced myelodysplastic syndromes/acute myeloid leukemia (MDS/AML). The projected probability of developing secondary cancers was 14.7% at 10 years and 24.8% at 19 years. Sureda et al.21 reported on 494 patients with HL post-ASCT and observed a secondary cancer rate of 4.3% at 5 years. Adjuvant radiotherapy before ASCT, the use of TBI in the transplant conditioning regimen, and age of 40 years or older were predictive factors for developing secondary cancers. However, whether this risk is from the ASCT conditioning regimen versus the earlier primary and salvage therapy that the patients had received is difficult to determine.

Forrest et al.22 compared the incidence of secondary cancers after standard therapy for HD with that among patients who also underwent ASCT. They analyzed 1732 consecutive patients, of whom 202 underwent ASCT. Median follow-up was 9.8 years for the entire cohort, 9.7 years for conventional therapy, and 7.8 years for ASCT. Cumulative incidence for secondary cancers was 9%. No difference was seen between conventional therapy alone and patients undergoing ASCT (9% and 8%, respectively; P = .498). In multivariate analysis, the important prognostic factor for developing any solid tumor was age of 35 years or older (P < .0001). An increased risk for therapy-induced secondary MDS/AML therapy was seen in patients aged 35 years or older (P = .03) and with stage IV disease (P = .04).

Clear risks are associated with ASCT, including secondary malignancies. Treatment with non-TBI–containing regimens may decrease this risk but has an uncertain effect on disease relapse. Currently, the risks of progressive HL seem to outweigh the risks of therapy.

Tandem ASCT for Relapsed HL

In an attempt to increase the effect of ASCT for relapsed HL, small studies have evaluated the use of sequential high-dose regimens, each given with stem cell support.23 Forty-six patients were treated and 11% (n = 5) were not given tandem ASCT because an inadequate number of stem cells were collected. The first ASCT used 150 mg/m2 of melphalan and the second transplant used fractionated TBI (1200 cGy) or 450 mg/m2 of carmustine (BCNU) in combination with etoposide (60 mg/kg) and cyclophosphamide (100 mg/kg). The second ASCT was performed a median of 64 days after the first ASCT (range, 25–105). With a median follow-up of 41 months in the patients who received both treatments, the 5-year overall survival, progression-free survival, and freedom from progression rates were 54%, 49%, and 55%, respectively.

Another study by the Italian group evaluated ASCT with 200 mg/m2 of melphalan followed by BEAM and ASCT. In an intent-to-treat analysis, overall response rates increased from 65% to 75% after the second ASCT.24 Czyz et al.25 reported on 35 patients who had undergone 2 ASCTs and compared outcomes with 105 patients who underwent a single ASCT. In a multivariate analysis, only disease status at second ASCT (complete response vs. partial response or progressive disease) was significant for worse event-free survival after the second ASCT (P = .004; relative risk, 2.3). A trend was seen toward better survival in patients who underwent 2 ASCTs (P = .01). The 5-year probability of survival after first ASCT in patients treated with 2 ASCTs was 83%.

The German Hodgkin Study Group H96 trial evaluated single versus tandem ASCT for patients with primary refractory or relapsed HL.26 Patients with poor-risk disease (primary refractory or 2 of the following: relapse < 12 months, stage III/IV at relapse, relapse in primary irradiated site after combined modality therapy) underwent tandem ASCT, whereas patients with one risk factor (intermediate risk) underwent a single ASCT. For poor-risk patients, 105 of 150 underwent tandem ASCT. In an intent-to-treat analysis, the 5-year freedom from second failure and overall survival rates were 46% and 57%, respectively. For intermediate-risk patients, 92 of 95 received a single ASCT, and an intent-to-treat analysis showed that the 5-year freedom from second failure and overall survival rates were 73% and 85%, respectively. The results with tandem transplant for poor-risk disease seem superior to other trials; however, prospective trials have not been performed.

Consideration of Maintenance Therapy Post-ASCT

Currently, no maintenance or immunotherapy therapy has been established as the standard of care after ASCT for HL. In general, immunotherapy has several obstacles, because tumors can express only weak antigens, may present them poorly, and evolve several immune evasion strategies that must be overcome, including regulatory T cells. It is also poorly understood which types of immune cells or combination of immune cells are needed to mount adequate and consistent immunologic control (T cells vs. B cells vs. natural killer cells). Nagler et al.27 reported on some benefit with IL-2 and interferon-α immunotherapy after ASCT in patients with NHL, but saw no benefit in patients with HL. The use of cloned autologous or allogeneic T cells for treating HL is in its infancy and also has been hampered by lack of tumor-specific antigens to target. Bollard et al.28 published interesting data showing some disease control after treating patients with autologous Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) cytotoxic cell lines. Research is ongoing in generating EBV-specific T-cell lines with anti-CD30 chimeric T-cell receptors.29

Finally, several new agents are showing high response rates in patients with relapsed HL. This is currently led by the anti–CD30 antibody–based construct brentuximab vedotin (SGN35; antibody to CD30 coupled with MMAE [monomethyl auristatin E]). Encouraging activity has been reported in patients experiencing relapse after ASCT,30,31 and the use of this drug–antibody construct is currently being studied in a multicenter randomized trial as maintenance treatment after ASCT.

AlloHCT

The use of an allogeneic stem cell source may provide additional antitumor activity when compared with ASCT, but is associated with a higher NRM. The use of allogeneic donor cells provides a tumor-free stem cell source and stem cells that have not been previously damaged by extensive chemotherapy or radiation therapy. This may decrease the incidence of secondary malignancies. In addition, the immune system of the donor may recognize minor antigen differences between the patient and donor, resulting in graft-versus-host reactions that may also attack tumor cells, causing graft-versus-tumor activity. However, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and its complications are also responsible for the increased NRM associated with alloHCT. The demonstration of graft-versus-tumor activity is supported by the responses to donor lymphocyte infusions (DLIs) for patients with persistent or relapsed disease (see later discussion).

Myeloablative alloHCT for HL

No randomized studies on the use of ASCT versus myeloablative alloHCT for HL have been performed, and all retrospective studies of these comparisons favor the safety profile of ASCT.32 Early transplant series of alloHCT for refractory HL generally had disappointing results. Report of 100 cases through the CIBMTR noted 3-year overall survival and progression-free survival rates of 21% and 15%, respectively.33 Thus, in most settings, patients with primary refractory or relapsed HL who can withstand high-dose therapy will receive ASCT. For the few patients who cannot have stem cells collected but who are candidates for high-dose therapy, alloHCT can be considered.

Conditioning regimens are usually based on chemotherapy alone or chemotherapy combined with TBI. Because many patients with relapsed HL have already received dose-limiting radiation, many of these regimens use chemotherapy alone. Table 3 shows results from several studies using myeloablative conditioning and alloHCT from either related or unrelated donors. In general, these regimens are used in patients who have not previously undergone high-dose therapy and ASCT. Attempts to use myeloablative regimens in patients for whom prior ASCT failed have resulted in prohibitive NRM and high relapse rates. An exception has been reported using the BEAM conditioning regimen in 10 of these patients, with a low day-100 NRM and evidence of graft-versus-tumor activity, but short follow-up.34 Comparisons of myeloablative conditioning versus RIC are problematic, because reduced-intensity regimens are favored in patients with extensive prior therapy or comorbidities. In general, higher NRM has been associated with myeloablative regimens and a greater risk of relapse associated with RIC approaches, leading to similar long-term outcomes for patients treated with each approach.35

Table 3.

Selected Trials of Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplant for Hodgkin Lymphoma

| Study | No. Patients | Graft | Regimen | NRM/TRM | OS (%) | PFS (%) | Relapse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myeloablative Conditioning | |||||||

| Gajewski et al.33 | 100 | MRD | Various, TBI: 45% | 3-y: 61 | 3-y: 21 | 3-y: 15 | 3-y: 65 |

| Milpied et al.32 | 45 | MRD | Various | 4-y: 48 | 4-y: 25 | 4-y: 15 | 4-y: 61 |

| Akpek et al.49 | 53 | MRD | Various | 10-y: 53 | 10-y: 30 | 10-y: 26 | 10-y: 53 |

| Reduced-Intensity Conditioning | |||||||

| Robinson et al.37 | 285 | MRD, URD | Various | 1-y: 19.5 | 3-y: 29 | 3-y: 25 | 5-y: 59 |

| 3-y: 21.1 | |||||||

| Sarina et al.38 | Donor: 63 vs. no donor: 185 | MRD, URD, Haplo | Various | 14 | 2-y: 66 | 2-y: 39 | NA |

| 5 | 2-y: 42 | 2-y: 14 | |||||

| Peggs et al.41 | (+) Mab: 31 | MRD,URD | Flu/Mel | 2-y: 7 | 4-y: 62 | 2-y: 39 | 3-y: 54 |

| (−) Mab: 36 | Flu/Mel | 2-y: 28 | 4-y: 39 | 2-y: 25 | 3-y: 44 | ||

| Devetten et al.50 | 143 | URD | Various | 2-y: 33 | 2-y: 37 | 2-y: 20 | 2-y: 47 |

| RIC | |||||||

| Anderlini et al.51 | 58 | MRD, URD | Flu/Mel | 2-y: 15 | 2-y: 64 | 2-y: 32 | 2-y: 55 |

| Alvarez et al.52 | 40 | MRD | Flu/Mel | 1-y: 25 | 2-y: 48 | 2-y: 32 | NA |

| Burroughs et al.40 | 90 total | ||||||

| 38 | MRD, URD | Flu/TBI | 1-y: 21 | 2-y: 53 | 2-y: 23 | 2-y: 56 | |

| 24 | Haplo | Flu/TBI | 1-y: 8 | 2-y: 58 | 2-y: 29 | 2-y: 63 | |

| 28 | Flu/TBI/Cy | 1-y: 9 | 2-y: 58 | 2-y: 51 | 2-y: 40 | ||

Abbreviations: Cy, cyclophosphamide; Flu, fludarabine; Haplo, haploidentical donor; Mab, alemtuzumab; Mel, melphalan; MRD, matched related donor; NA, not available; NRM, nonrelapse mortality; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning; TBI, total body irradiation; TRM, transplant-related mortality; URD, unrelated donor.

Reduced-Intensity and Nonmyeloablative AlloHCT

The past 10 to 15 years have seen a radical change in the approach to alloHCT. Previously, high-dose conditioning was thought to be necessary for preventing graft rejection, making marrow space, and providing antitumor activity. These criteria limited treatment to younger patients and those without medical comorbidities. Recognition that nonmyeloablative conditioning or RIC could be sufficient to allow allogeneic engraftment, and that graft-versus-host reactions could eliminate host hematopoiesis and provide antitumor effects, has widened the use of alloHCT. This has allowed treatment to be considered in older patients, or patients with comorbidities, including those with HL for whom prior ASCT failed. A wide variety of conditioning regimens have been used that vary in intensity, from truly nonmyeloablative (fludarabine, 90 mg/m2, and TBI, 2 Gy) to RIC regimens approaching the intensity of standard conditioning regimens. The lower-intensity regimens can often be administered in the outpatient clinic.

Most patients with HL currently treated with alloHCT, have previously failed ASCT. This generally requires the use of RIC for subsequent alloHCT. Table 3 shows the outcome of several series, and the role of alloHCT in patients with HL has also been reviewed recently.36 Currently, no consensus exists on the optimal conditioning regimen or donor type.

Robinson et al.37 reported on the largest series from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, consisting of 285 patients with HL, most with sensitive relapsed disease, and 80% who had undergone prior ASCT and received reduced-intensity alloHCT. Overall, results showed a low 1-year transplant-related mortality of 11%, but a 5-year progression rate of 59% without a clear plateau on the progression curve. This led to 3-year overall survival of 29% and progression-free survival of 25%.

A recent publication by Sarina et al.38 used a retrospective donor-versus-no donor analysis of 185 patients with relapsed HL after prior ASCT, among whom 66% had a suitable donor (related, unrelated, or haploidentical) and 85% underwent alloHCT. Comparison of outcomes of patients with a donor and those without a donor showed improved 2-year (and 4-year) overall and progression-free survival rates in those with a donor (66% vs. 42% and 39% vs. 14%, respectively; P < .001). This and other retrospective analyses suggest that RIC alloHCT may be superior to conventional salvage therapy in patients for whom ASCT failed,39 and support the need for definitive trials.

The authors reported on a series of 90 patients with relapsed HL treated with nonmyeloablative conditioning and alloHCT using sibling, unrelated, and haploidentical related donors.40 ASCT and prior radiation therapy failed in most patients (92% and 83%). The 2-year overall survival rates, progression-free survival rates, and incidences of relapse/progression were 53%, 23%, and 56% for HLA-matched related donors; 58%, 29%, and 63% for matched unrelated donors; and 58%, 51%, and 40% for haploidentical donors, respectively. Surprisingly, the NRM was lower for haploidentical transplant recipients compared with HLA-matched recipients (P = .02). The conditioning regimen for the haploidentical alloHCT included additional pre- and posttransplant cyclophosphamide to control GVHD, and may have also had an effect on HL cells or other regulatory T-cell subsets. Overall, no clear consensus exists on optimal graft source (related, unrelated, or haploidentical).

Role of T-Cell Depletion

Decreasing the T-cell content of the graft through either in vivo or ex vivo manipulation can clearly decrease the incidence of significant GVHD. Peggs et al.41 explored the use of in vivo alemtuzumab (anti-CD52 antibody) with fludarabine and melphalan conditioning for the treatment of relapsed HL. They reported on a series of 67 patients treated either with (n = 31) or without (n = 36) alemtuzumab. Compared with the fludarabine/melphalan conditioning–only group, the use of alemtuzumab was associated with a lower 2-year transplant-related mortality (7% vs. 29%, respectively) and similar 3-year incidences of relapse (54% vs. 44%, respectively). Overall, this led to a better 3-year progression-free survival rate of 43% versus 25% for the alemtuzumab-containing regimen. Patients in alemtuzumab group more frequently required a DLI for persistent or progressive disease post-alloHCT (see later discussion). It is also possible that alemtuzumab may have had direct antitumor effects on the HL cells or altered T-cell subsets. Thus, alemtuzumab seemed to decrease the risk of GVHD and complications but increase the need for subsequent DLI.

DLIs

Patients who have persistent disease or experience relapse post-alloHCT may be able to be treated with DLIs. Peggs et al.42 reported on 49 patients treated with fludarabine and melphalan conditioning and in vivo T-cell depletion with alemtuzumab. Patients were heavily pretreated, with 90% having undergone prior ASCT. Because of residual disease or disease progression, 33% received DLI beginning 3 months post-alloHCT. DLI was associated with the induction of grade II through IV GVHD in 38% of patients and NRM of 16% at 2 years. However, 56% of patients experienced response to DLI, leading to 4-year overall survival and progression-free survival rates of 56% and 39%, respectively. DLI is required more frequently after alloHCT using T-cell depletion, but can also be considered in patients experiencing persistent disease or relapse post-alloHCT as long as they do not have significant ongoing GVHD. Responses after DLI and the suggestion of improved disease control in patients who develop chronic GVHD provide the best evidence for the existence of graft-versus-HL activity of alloHCT.

Conclusions

Currently, high-dose therapy and ASCT is the standard of care for patients with chemotherapy-sensitive relapsed or primary refractory HL. Patients with negative functional imaging before ASCT have better outcomes. Whether patients with chemosensitive disease but persistent positive functional imaging will benefit from additional salvage therapy before ASCT remains to be determined. No consensus exists on the optimal conditioning regimen for ASCT or the role of tandem ASCT. The management of patients with refractory disease or those who experience relapse after ASCT remains a challenge. The use of RIC alloHCT can salvage some patients and should be considered, especially if the disease can be controlled to a minimal state pretransplant. Many questions remain regarding the optimal conditioning regimens, the use of T-cell depletion, DLI, and the optimal donor source of stem cells. With each of these approaches, the incorporation of targeted therapies into conditioning regimens or as maintenance therapy posttransplant may further improve outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants CA78902, CA15704, and CA18029.

Footnotes

Dr. Holmberg has disclosed that she receives clinical trial funding from Seattle Genetics, Inc. Dr. Maloney has disclosed that he has no financial interests, arrangements, or affiliations with the manufacturers of any products discussed in this article or their competitors.

References

- 1.Bartlett NL. Modern treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma. Curr Opin Hematol. 2008;15:408–414. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328302c9d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engert A, Diehl V, Franklin J, et al. Escalated-dose BEACOPP in the treatment of patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma: 10 years of follow-up of the GHSG HD9 study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4548–4554. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moskowitz AJ, Yahalom J, Kewalramani T, et al. Pretransplantation functional imaging predicts outcome following autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2010;116:4934–4937. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmitz N, Pfistner B, Sextro M, et al. Aggressive conventional chemotherapy compared with high-dose chemotherapy with autologous haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for relapsed chemosensitive Hodgkin’s disease: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2065–2071. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08938-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmitz N, Haverkamp H, Josting A, et al. Long term follow up in relapsed Hodgkin’s disease (HD): updated results of the HD-R1 study comparing conventional chemotherapy (cCT) to high-dose chemotherapy (HDCT) with autologous haemopoetic stem cell transplantation (ASCT) of the German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG) and the Working Party Lymphoma of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) J Clin Oncol. 2005;23 Suppl 16S [abstract] Abstract 6508. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linch DC, Winfield D, Goldstone AH, et al. Dose intensification with autologous bone-marrow transplantation in relapsed and resistant Hodgkin’s disease: results of a BNLI randomised trial. Lancet. 1993;341:1051–1054. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92411-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasquini MC, Wang Z. Current use and outcome of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: CIBMTR Summary Slides. [Accessed July 26, 2011];2010 Available at: http://www.cibmtr.org.

- 8.Sureda A, Constans M, Iriondo A, et al. Prognostic factors affecting long-term outcome after stem cell transplantation in Hodgkin’s lymphoma autografted after a first relapse. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:625–633. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sirohi B, Cunningham D, Powles R, et al. Long-term outcome of autologous stem-cell transplantation in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1312–1319. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasenclever D, Diehl V. A prognostic score for advanced Hodgkin’s disease. International Prognostic Factors Project on Advanced Hodgkin’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1506–1514. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Constans M, Sureda A, Terol MJ, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for primary refractory Hodgkin’s disease: results and clinical variables affecting outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:745–751. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lazarus HM, Rowlings PA, Zhang MJ, et al. Autotransplants for Hodgkin's disease in patients never achieving remission: a report from the Autologous Blood and Marrow Transplant Registry. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:534–545. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.2.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sweetenham JW, Carella AM, Taghipour G, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation for adult patients with Hodgkin’s disease who do not enter remission after induction chemotherapy: results in 175 patients reported to the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Lymphoma Working Party. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3101–3109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gopal AK, Metcalfe TL, Gooley TA, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for chemoresistant Hodgkin lymphoma: the Seattle experience. Cancer. 2008;113:1344–1350. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Persky DO, Moskowitz CH, Filatov A, et al. High dose chemoradiotherapy and ASCT may overcome the prognostic importance of biologic markers in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2010;18:35–40. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3181b473b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Josting A, Rueffer U, Franklin J, et al. Prognostic factors and treatment outcome in primary progressive Hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the German Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2000;96:1280–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vigouroux S, Milpied N, Andrieu JM, et al. Front-line high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation for high risk Hodgkin’s disease: comparison with combined-modality therapy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29:833–842. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Federico M, Bellei M, Brice P, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation versus conventional therapy for patients with advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma responding to front-line therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2320–2325. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith SM, van Besien K, Carreras J, et al. Second autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed lymphoma after a prior autologous transplant. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:904–912. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moskowitz CH, Yahalom J, Zelenetz AD, et al. High-dose chemo-radiotherapy for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma and the significance of pre-transplant functional imaging. Br J Haematol. 2010;148:890–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.08037.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sureda A, Arranz R, Iriondo A, et al. Autologous stem-cell transplantation for Hodgkin’s disease: results and prognostic factors in 494 patients from the Grupo Espanol de Linfomas/Transplante Autologo de Medula Osea Spanish Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1395–1404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forrest DL, Hogge DE, Nevill TJ, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation does not increase the risk of second neoplasms for patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a comparison of conventional therapy alone versus conventional therapy followed by autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7994–8002. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.9083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fung HC, Stiff P, Schriber J, et al. Tandem autologous stem cell transplantation for patients with primary refractory or poor risk recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castagna L, Magagnoli M, Balzarotti M, et al. Tandem high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation in refractory/relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a monocenter prospective study. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:122–127. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Czyz J, Dziadziuszko R, Knopinska-Posluszny W, et al. Two autologous transplants in the treatment of patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma: analysis of prognostic factors and comparison with a single procedure. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:535–541. doi: 10.1080/10428190601158621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morschhauser F, Brice P, Ferme C, et al. Risk-adapted salvage treatment with single or tandem autologous stem-cell transplantation for first relapse/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma: results of the prospective multicenter H96 trial by the GELA/SFGM study group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5980–5987. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.5887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagler A, Berger R, Ackerstein A, et al. A randomized controlled multicenter study comparing recombinant interleukin 2 (rIL-2) in conjunction with recombinant interferon alpha (IFN-alpha) versus no immunotherapy for patients with malignant lymphoma postautologous stem cell transplantation. J Immunother. 2010;33:326–333. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181c810b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bollard CM, Aguilar L, Straathof KC, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte therapy for Epstein-Barr virus+ Hodgkin’s disease. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1623–1633. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Savoldo B, Rooney CM, Di Stasi A, et al. Epstein Barr virus specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes expressing the anti-CD30zeta artificial chimeric T-cell receptor for immunotherapy of Hodgkin disease. Blood. 2007;110:2620–2630. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-059139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Younes A, Bartlett NL, Leonard JP, et al. Brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) for relapsed CD30-positive lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1812–1821. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen R, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Results of a pivotal phase 2 study of brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2010;116 doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-595801. [abstract] Abstract 283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milpied N, Fielding AK, Pearce RM, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplant is not better than autologous transplant for patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s disease. European Group for Blood and Bone Marrow Transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1291–1296. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.4.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gajewski JL, Phillips GL, Sobocinski KA, et al. Bone marrow transplants from HLA-identical siblings in advanced Hodgkin’s disease. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:572–578. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.2.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooney JP, Stiff PJ, Toor AA, Parthasarathy M. BEAM allogeneic transplantation for patients with Hodgkin’s disease who relapse after autologous transplantation is safe and effective. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9:177–182. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2003.50007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sureda A, Robinson S, Canals C, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning compared with conventional allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an analysis from the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:455–462. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klyuchnikov E, Bacher U, Kroger N, et al. The role of allogeneic stem cell transplantation in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s Lymphoma patients. Adv Hematol. 2011;2011:974658. doi: 10.1155/2011/974658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson SP, Sureda A, Canals C, et al. Reduced intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation for Hodgkin’s lymphoma: identification of prognostic factors predicting outcome. Haematologica. 2009;94:230–238. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarina B, Castagna L, Farina L, et al. Allogeneic transplantation improves the overall and progression-free survival of Hodgkin lymphoma patients relapsing after autologous transplantation: a retrospective study based on the time of HLA typing and donor availability. Blood. 2010;115:3671–3677. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-253856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomson KJ, Peggs KS, Smith P, et al. Superiority of reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation over conventional treatment for relapse of Hodgkin’s lymphoma following autologous stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41:765–770. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burroughs LM, O’Donnell PV, Sandmaier BM, et al. Comparison of outcomes of HLA-matched related, unrelated, or HLA-haploidentical related hematopoietic cell transplantation following nonmyeloablative conditioning for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:1279–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peggs KS, Sureda A, Qian W, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning for allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: impact of alemtuzumab and donor lymphocyte infusions on long-term outcomes. Br J Haematol. 2007;139:70–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peggs KS, Hunter A, Chopra R, et al. Clinical evidence of a graft-versus-Hodgkin’s-lymphoma effect after reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation. Lancet. 2005;365:1934–1941. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66659-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stiff PJ, Unger JM, Forman SJ, et al. The value of augmented preparative regimens combined with an autologous bone marrow transplant for the management of relapsed or refractory Hodgkin disease: a Southwest Oncology Group phase II trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2003;9:529–539. doi: 10.1016/s1083-8791(03)00205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tarella C, Cuttica A, Vitolo U, et al. High-dose sequential chemotherapy and peripheral blood progenitor cell autografting in patients with refractory and/or recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma: a multicenter study of the intergruppo Italiano Linfomi showing prolonged disease free survival in patients treated at first recurrence. Cancer. 2003;97:2748–2759. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wadehra N, Farag S, Bolwell B, et al. Long-term outcome of Hodgkin disease patients following high-dose busulfan, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, and autologous stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:1343–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Czyz J, Dziadziuszko R, Knopinska-Postuszuy W, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors in advanced Hodgkin’s disease treated with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation: a study of 341 patients. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1222–1230. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Engelhardt BG, Holland DW, Brandt SJ, et al. High-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: prognostic features and outcomes. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:1728–1735. doi: 10.1080/10428190701534374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lavoie JC, Connors JM, Phillips GL, et al. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for primary refractory or relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma: long-term outcome in the first 100 patients treated in Vancouver. Blood. 2005;106:1473–1478. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Akpek G, Ambinder RF, Piantadosi S, et al. Long-term results of blood and marrow transplantation for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4314–4321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.23.4314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Devetten MP, Hari PN, Carreras J, et al. Unrelated donor reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderlini P, Saliba R, Acholonu S, et al. Fludarabine-melphalan as a preparative regimen for reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation in relapsed and refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma: the updated M.D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Haematologica. 2008;93:257–264. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alvarez I, Sureda A, Caballero MD, et al. Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation is an effective therapy for refractory or relapsed hodgkin lymphoma: results of a spanish prospective cooperative protocol. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:172–183. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]