Using a transgenic mouse system, the authors demonstrated that in the absence of TGF-β signaling corneal wound healing is significantly delayed. In addition, they provide evidence that at the early stages of wound healing, suppression of proliferation is maintained through JNK activation of ATF2 in the absence of TGF-β signaling.

Abstract

Purpose.

The aim of this study was to elucidate the mechanisms governing epithelial cell migration and proliferation during wound healing.

Methods.

The authors used wound healing of mouse corneal epithelium to examine the role TGF-β signaling plays during the healing process. To achieve this goal, they used transgenic mice in which the TGF-β receptor type II (Tbr2) was conditionally ablated from the corneal epithelium. Epithelium debridement wounds were made, followed by the assessment of cell migration, proliferation, and immunostaining of various signaling pathway components.

Results.

The authors showed that in the absence of TGF-β signaling corneal epithelial wound healing is delayed by 48 hours; this corresponds to a delay in p38MAPK activation. Despite the delayed p38MAPK activation, ATF2, a substrate of p38MAPK, is still phosphorylated, leading to the suppression of cell proliferation at the leading edge of the wound. These data provide evidence that in the absence of TGF-β signaling, the suppression of cell proliferation during the early stages of wound healing is maintained through the JNK activation of ATF2.

Conclusions.

Together the data presented here demonstrate the importance of the TGF-β and MAPK signaling pathways in corneal epithelial wound healing.

Corneal epithelial homeostasis is critical for maintaining epithelial integrity and normal vision. Perturbations of corneal epithelial cell homeostasis, such as epithelial hypertrophy, stem cell deficiency, and injury, have serious consequences that lead to vision impairment. Injury to the epithelium must be rapidly healed to avoid further damage from microbial infection. Healing of corneal epithelial wounds involves several processes, two of which are cell proliferation and cell migration. During the early stages of wound healing, epithelial cell proliferation must be suppressed at the wound edge in order for cell migration to ensue. Once the denuded area has been covered by the migrating epithelium, cell proliferation increases to reestablish the stratified epithelium. One growth factor that is believed to regulate the various events of wound healing is transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β).

Members of the TGF-β family and their receptors have been shown to be expressed by the corneal epithelium and at lower levels by stromal keratocytes under normal physiological conditions.1–9 During pathogenetic events such as corneal wounding, these ligands and receptors are strongly upregulated before they return to baseline,5,10 when the injured tissue heals. TGF-β ligands signal through type I and type II heteromeric transmembrane Ser/Thr kinase receptors (Tbr-I and Tbr-II). The type III TGF-β receptor (Tbr-III) facilitates binding of TGF-β to Tbr-II. Activation of Tbr-I by phosphorylation is mediated by Tbr-II and is dependent on ligand binding to Tbr-II. In the canonical TGF-β pathway, activated Tbr-I propagates its signal through the Smad family of transcription factors. Smad2 and Smad3 are phosphorylated at their C terminus by Tbr-I, leading to their homodimerization or heterodimerization and binding with Smad4, after which this complex translocates to the nucleus and serves as a transcription factor to activate or suppress target genes.11,12 We have previously demonstrated that healing of the corneal epithelium is delayed by the administration of TGF-β–neutralizing antibodies; this effect is primarily mediated by the activation of p38MAPK instead of the Smad signaling pathway.13 Activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2) is a member of the bZIP family of transcription factors and is activated on its phosphorylation by stress-activated kinases (e.g., JNK and p38MAPK) in response to stress and cytokine stimuli.14,15 Phospho-ATF2 self-dimerizes or dimerizes with other members of the AP-1 family and serves as a transcription factor in the regulation of transcription factors and proteins engaged in stress and DNA damage, the regulation of genes associated with growth and tumorigenesis, and the regulation of genes important for maintenance and physiological homeostasis.16 It has been shown that ATF2 inhibits the proliferation of human cancer cells by blocking the G1/S transition of the cell cycle by decreasing ERK expression.17 The role of ATF2 in the suppression of cell proliferation is further supported by the observation that ATF2 can associate with the retinoblastoma gene product (pRB) to enhance the expression of TGF-β1 and thus augments a loop of the inhibition of cell proliferation through TGF-β signaling.18 It has recently been demonstrated that ATF2 is also involved in the repair of DNA damage and serves as a tumor suppressor.16,19,20

In the present study, we sought to determine whether the activation of p38MAPK is essential and sufficient in regulating cell migration and proliferation during corneal epithelium wound healing. To address this question, transgenic mice were created using a Krt12 (keratin 12) promoter-driven mouse line to conditionally ablate Tbr2 in corneal epithelial cells. The data presented here further highlight the importance of TGF-β signaling for proper epithelial cell migration during the wound healing process. In addition, we show that in the absence of p38MAPK activation, JNK can activate ATF-2, leading to the suppression of proliferation. Taken together, these data demonstrate a novel regulatory pathway during the process of corneal wound healing.

Materials and Methods

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Wakayama Medical University and from the University of Cincinnati Medical Center.

Transgenic Mice

To prepare mice lacking TGF-β receptor 2 (Tbr2) in the corneal epithelium in utero, Tbr2 floxed (Tbr2f/f) mice21 were bred to Krt12Cre/w mice (Fig. 1A), after which bitransgenic mice were mated to generate mice in which the Tbr2 gene was constitutively and selectively ablated in the corneal epithelium. To avoid promiscuous cre activity,22 in another series of experiments, triple transgenic Krt12rtTA/rtTA/ tet-O-Cre/Tbr2f/f mice were generated by cross-breeding among Krt12rtTA/rtTA/tet-O-Cre and Tbr2f/f mice, in which Tbr2 was ablated by the administration of doxycycline to the experimental mice (intraperitoneal injection of doxycycline 80 μg/g body weight, followed by feeding of 0.1% doxycycline chow for 2 weeks). Genotypes of experimental mice were identified by PCR of tail DNA (Fig. 1B). Primers for Krt12-Cre mice were 5′-GTCGGTCCGGGCTGCCACGACC-3′ and 5′-CTTCCAGCAGGCGCACCATTGC-3′. Primers for TGF-β receptor 2 floxed (Tbr2f/f) mice were 5′-TTCCCGAAATGAGCTAGAGGC-3′ and 5′-TGTTGCCTGGGCACAACACC-3′. Primers for detection of gene excision were 5′-TTCCCGAAATGAGCTAGAGGC-3′ and 5′-AGAGTGAAGCCGTGGTAGGTGAGCTTG-3′. Annealing temperatures were 68°C, 64°C, and 55°C, respectively. Experimental mice Krt12Cre/Cre/Tbr2f/f and Krt12rtTA/rtTA/tet-O-Cre/Tbr2f/f mice (doxycycline induction as described) were defined as Tbr2ceΔ/ceΔ (corneal epithelium ablation of Tbr2) mice; Krt12Cre/Cre/Tbr2f/w(wild type) and Krt12rtTA/rtTA/tet-O-Cre/Tbr2f/w (fed doxycycline) as Tbr2ceΔ/w mice; Krt12w/w/Tbr2f/f and Krt12rtTA/rtTA/tet-O-Cre/Tbr2f/f (fed normal chow) as Tbr2cef/cef mice. To confirm the event of DNA excision and the absence of Tbr2 protein, the corneal epithelium of Tbr2ceΔ/ceΔ, Tbr2ceΔ/w, Tbr2cef/cef, and Tbr2w/w mice was collected and then genotyped by PCR and Western blot analysis using an anti-Tbr2 antibody (sc-220; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were performed after the extraction of genomic DNA and protein (Figs. 1B–D). It should be noted that Krt12 is subject to monoallelic expression23; thus, it was imperative that the driver mice be homozygous Krt12Cre/Cre and Krt12rtTA/rtTA to ablate genes of interest in every Krt12-positive cell.

Figure 1.

Generation and morphology of conditional Tbr2 ablation in the corneal epithelium of Tbr2ceΔ/ceΔ mice. (A) To prepare mice lacking TGF-β receptor type II (Tbr2) in the corneal epithelium, Tbr2 floxed mice were bred to Krt12-Cre mice. Arrows: primers used for genotyping and detection of gene excision. (B) Genotyping and excision PCR of corneal epithelium. Tbr2 gene of Krt12Cre/Cre/Tbr2f/f mouse corneal epithelium was excised completely. NC, no DNA control; M, molecular size markers. (C) Tbr2 Western blot analysis. (D) Tbr2 immunofluorescence. Red: Tbr2 expression; green: nuclear counterstain. (E–J) Corneal morphology by hematoxylin-eosin staining reveals a relatively normal-looking corneal epithelium with dividing cells located in the basal epithelium after loss of Tbr2. (E–G) Low magnification. (H–J) High magnification. Krt12 expression did not change in the absence of Tbr2 (K–M). Red: Krt12.

Corneal Epithelial Debridement

Two-month-old Tbr2ceΔ/ceΔ, Tbr2ceΔ/w, Tbrcef/cef, and Tbr2w/w mice were anesthetized by combined intraperitoneal administration of xylazine (13 mg/kg) and ketamine (87 mg/kg), and the central corneal epithelium (2 mm in diameter) was demarcated with a trephine (Tru-Punch; Sklar, West Chester, PA) and subsequently removed using a healing brush (Algerbrush II; Alger Company, Lago Vista, TX) under a stereomicroscope. Neomycin ointment was topically applied to prevent bacterial infection. The injured corneas were allowed to heal for various periods of time (0–72 hours). Affected eyes at each time point (0, 12, 24, and 48 hours) were stained with sodium fluorescein and photographed with a stereomicroscope (Stemi SV 11 Apo; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) to evaluate reepithelialization. The area of defect was measured using microscopic imaging software (AxioVision; Carl Zeiss) and was statistically analyzed. All experimental animals were intraperitoneally administered BrdU (80 μg/g body weight) 2 hours before euthanasia.

Inhibition of JNK

The JNK peptide inhibitor (GRKKRRQRRR-PP-RPKRPTTLNLFPQVPRSQD-amide; catalog no. ALX-159-600-R100) and the control peptide (RKKRRQRRR-amide; catalog no. ALX-168-009-R050) were obtained from Alexis (San Diego, CA); 1 mM each was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted with PBS to 5 μM. Experimental Tbr2ceΔ/ceΔ mice were anesthetized as described. Epithelial debridement (2 mm) was created with a healing brush (Algerbrush II; Alger Company), and 25 μL peptide solution was applied to the injured corneas every 15 minutes for 2 hours. The injured corneas were allowed to heal for 6 hours before they were collected. Two hours before euthanasia, BrdU (80 μg/g body weight) was intraperitoneally administered to the experimental mice. The excised corneas were then subjected to morphologic examination with hematoxylin-eosin staining, immunofluorescence, and whole mount immunostaining as described.

Histologic Observation

Enucleated eyes at each time point were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at 4°C overnight. Specimens were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series and were paraffin embedded or processed for cryosection. Five-micrometer sections were used for hematoxylin-eosin staining, immunohistochemistry, and immunofluorescence.

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence Staining

Paraffin sections (5-μm thick) were processed for immunohistochemistry for BrdU phospho-p38MAPK, and phospho-ATF2. For BrdU immunostaining, paraffin sections were treated with 2 N HCl for 1 hour at 37°C, washed in PBS before blocking with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature, and then incubated with anti–BrdU antibody (1:1000 dilution in PBS; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) for 1 hour at room temperature. After washes in PBS, the specimens were treated with peroxidase-conjugated anti–mouse immunoglobulin for 1 hour at room temperature. After another wash in PBS, a peroxidase reaction was performed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as previously reported.24 After counterstaining with methyl green, the sections were mounted in balsam and observed under light microscopy. Alternatively, fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies were used to detect the cells labeled by BrdU. The number of BrdU-positive cells was counted as previously described.13 For phospho-p38MAPK immunostaining, after blocking with 2% BSA in PBS, the sections were incubated with rabbit monoclonal anti–phospho-p38MAPK antibody (1:100 dilution in PBS; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) for 12 hours at 4°C. After washes in PBS, ABC detection (Vectastain Elite staining kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was applied according to the manufacturer's protocol. Peroxidase reaction was also performed with DAB and counterstained with methyl green.

Immunofluorescence staining was also performed with anti–TGF-β receptor 2 (Tbr2), keratin 12 (Krt12), phospho-P38 (1:100; Cell Signaling), and phospho-ATF2 (1:100; Epitomics, Burlingame, CA), rabbit polyclonal antibody against Tbr2 (sc-220; 1:200 dilution in PBS; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Krt12 (1:200 dilution in PBS; original). After washing with PBS, immunostaining was performed as previously described25 with minor modifications. Briefly, directions and components from the ABC detection (Vectastain Elite; Vector Laboratories) staining kit were used with the following exception: Cy3–conjugated avidin (Rockland) was substituted for the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex. Excess Cy3–conjugated avidin was removed from the sections by washing three times for 10 minutes each in PBS at room temperature. Sections were counterstained with a nuclear stain (Yo-Pro-1; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and the sections were detected by fluorescence microscopy after mounting with mounting medium (VectaShield, H-1000; Vector Laboratories).

BrdU Analysis with Paraffin Sections

Cell proliferation was determined by intraperitoneal administration of BrdU (80 μg/g body weight) 2 hours before euthanasia. Incorporation of BrdU was detected by immunohistochemistry with anti–BrdU antibodies. The number of BrdU-labeled cells in two different slides from an experimental mouse was determined under a microscope. The corneal epithelium was divided into five zones: the central zone, 200 μm in diameter, was marked, and the remaining area on each side was then divided into two regions, a midperipheral area and a peripheral area. The incidence of BrdU-positive cells in these areas was determined.

Whole Mount Immunostaining

For whole mount immunostaining using anti–p-ATF2 (Epitomics) and anti–p-p38MAPK (Cell Signaling Technology) antibodies, corneas fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, were washed with PBS and pretreated with 50% TD (0.5% DMSO, 0.5% Triton X-100, 2.5% dextran 40) in PBS, pH 7.4, for 1 hour at 4°C. The specimens were rinsed with Tris-saline (0.15 M NaCl, 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4) three times for 15 minutes, incubated with conjugated primary antibodies in 50% TD containing 1 mg/mL BSA at 4°C overnight, and then washed with Tris saline and imaged under a fluorescence microscope with a structured illumination attachment (ApoTome; Carl Zeiss).

For BrdU staining, the specimens were treated with 2 N HCl at room temperature for 1 hour and neutralized with three washes of Tris saline. The specimens were subjected to immunostaining with an anti–BrdU-conjugated antibody as described above.

Whole Mount Phalloidin Staining

Animals were euthanized 12 hours after debridement, and the corneas were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 4 days. Samples were washed with PBS three times for 5 minutes each at room temperature, incubated in 70% ethanol for 30 minutes at room temperature, washed in PBS three times, incubated with Alexa Fluor 647 phalloidin (Molecular Probes) (5 U/mL) for 1 hour at room temperature, counterstained (Syto 59; Molecular Probes), and then flat mounted on glass slides in mounting medium (VectaShield, H-1000; Vector Laboratories). Images were captured by confocal microscopy (Confocal 510; Carl Zeiss).

Statistical Analysis

All results were analyzed statistically by Student's t-test. P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Tbr2 Deletion in Transgenic Mice

In Krt12Cre/w/Tbr2f/f mice, deletion of the Tbr2 gene was not 100% complete. In mice heterozygous for the Krt12-Cre gene, excision was performed in approximately half the corneal epithelial cells because of the monoallelic nature of the expression of the Krt12 gene.23 To have Tbr2 removed from all the corneal epithelial cells, mice were bred to homozygosity, which generated Krt12Cre/Cre/Tbr2f/f (Tbr2ceΔ/ceΔ) mice. Corneal wound healing of these mice was compared with that of Krt12Cre/Cre/Tbr2f/w (Tbr2ceΔ/w) and Krt12Cre/Cre/Tbr2w/w (Tbr2w/w) mice. In Tbr2ceΔ/ceΔ mice, Tbr2 was nearly absent at both the gene and the protein levels (Figs. 1A–D).

Loss of Tbr2 Delays Corneal Epithelial Wound Healing

Loss of Tbr2 from the corneal epithelium did not significantly disrupt corneal epithelial homeostasis under physiological conditions (i.e., without epithelial debridement). Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a corneal epithelium of average thickness and morphology. We also observed an increase in the number of basal epithelial cells undergoing cell division compared with controls (Tbr2ceΔ/w and Tbr2w/w mice) (Figs. 1E–M); however, a more accurate assessment of proliferation is described here. Keratin 12, a marker of differentiated corneal epithelium, expression was also unchanged in the absence of Tbr2 (Figs. 1K–M).

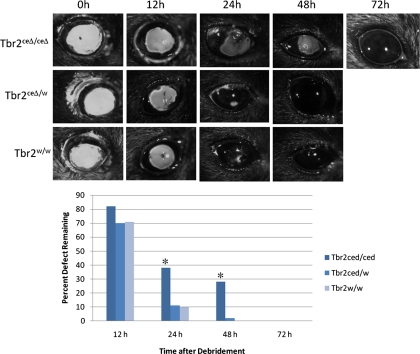

Debridement wounds were generated to determine what effect ablating Tbr2 had on the healing process. In the absence of TGF-β signaling, wound healing was delayed by approximately 48 hours, as indicated by the uptake of sodium fluorescein (Fig. 2). To address the reason for this delay, we examined cell proliferation and cell migration, two critical steps in the process of corneal epithelial wound healing.

Figure 2.

Delay in corneal epithelial wound healing. Sodium fluorescein stain was used to measure the defective area remaining at various times after debridement. (A) The eyes were photographed under a stereomicroscope, and the area was determined using microscopic imaging software and statistically analyzed and plotted graphically. (B) *P < 0.05. Error bar, SE.

Loss of Tbr2 Did Not Affect Suppression of Proliferation after Epithelial Debridement but Did Slow Migration

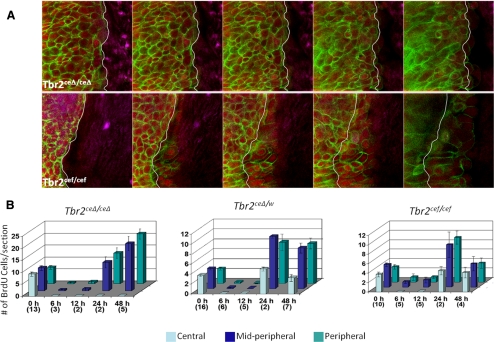

To examine whether the delay in wound healing was a result of cell migration, corneas isolated from transgenic mice 12 hours after wounding were stained for F-actin by phalloidin. In the absence of Tbr2, the expansion of actin stress fibers at the leading edge of the corneal wound was suppressed (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Effects of Tbr2 ablation on migration and proliferation during corneal wound healing. Corneal epithelial debridement was created in Tbr2ceΔ/ceΔ and Tbr2cef/cef mice. (A) For cell migration, the cornea was examined 12 hours after injury by staining with FITC-phalloidin (green) conjugate and nuclear counterstaining (red). Corneas were examined under a confocal microscope with a Z-stack, beginning from the basal epithelial cell layer (left) and proceeding to the superficial cell layer (right). White lines: initial wound edge. Ablation of Tbr2-impaired corneal epithelial migration. (B) Corneal epithelial debridement was performed with Tbr2ceΔ/ceΔ, Tbr2ceΔ/w, and Tbr2cef/cef mice and was allowed to heal for various time points. BrdU was administered 2 hours before euthanasia. BrdU incorporation was assessed in three areas of the cornea; central, midperipheral, and peripheral. Suppression of cell proliferation occurred within 12 hours after epithelial debridement independent of TGF-β signaling. Error bar, SE. Numbers in parentheses (x-axis) represent the number of animals used.

In another experiment, proliferation was examined by BrdU incorporation after epithelial debridement. In the presence of at least one copy of wild-type Tbr2, cell proliferation peaked at 24 hours, when the epithelium had covered the denuded area, and returned to baseline levels once the cornea was completely healed (48 hours). However, in the absence of Tbr2, the number of BrdU-positive cells increased steadily at 24 hours and 48 hours within the midperipheral and peripheral areas of the cornea. Proliferation in the central region was still suppressed because the epithelium had not yet migrated to cover the denuded area. Despite the fact that in the absence of Tbr2 there was a higher number of BrdU-positive cells in the naive, uninjured corneal epithelium, cell proliferation was suppressed during the early stages of wound healing in both the presence and the absence of Tbr2 (Fig. 3B). This suggests that the mechanism leading to the suppression of cell proliferation is still present in the absence of TGF-β signaling.

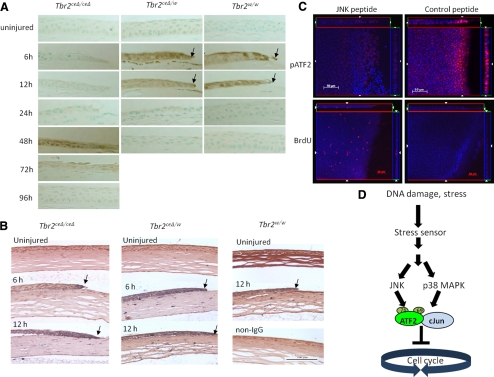

Activation of p38MAPK but Not ATF2 Is Delayed in the Absence of Tbr2

Our previous report13 indicated that the effect of TGF-β signaling on the healing of corneal epithelial debridement is mediated through the activation of p38MAPK; therefore, we examined its expression. In the absence of Tbr2, activation of p38MAPK was delayed by 48 hours compared with that of control mice. Uninjured corneas of mice lacking Tbr2 did not express activated p38MAPK (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Activation of ATF2 by JNK in the absence of Tbr2. Corneal epithelial debridement was performed with Tbr2ceΔ/ceΔ, Tbr2ceΔ/w, and Tbr2w/w mice, was allowed to heal for various times, and was examined by immunohistochemistry. (A, B) There was a delay of p38MAPK activation (A) in corneas of Tbr2ceΔ/ceΔ mice in comparison with the controls, but the activation of ATF2 was unaffected by the loss of Tbr2 (B). (C) To demonstrate that JNK may lead to the activation of ATF2 in the absence of Tbr2, corneas were treated with a JNK peptide inhibitor after epithelial debridement on Tbr2ceΔ/ceΔ mice and were examined for BrdU incorporation and ATF2 activation. In the presence of the JNK peptide inhibitor, ATF2 was not activated and cell proliferation was no longer suppressed 6 hours after wounding. (D) Stress from tissue injury triggered the activation of ATF2 by the phosphorylation of T69 and T71 residues by JNK and p38MAPK. Phospho-ATF2 can dimerize with itself or with other AP-1 family members, such as c-Jun. The activated ATF2-AP-1 complex blocked the cell cycle at the G1/S transition point.

As mentioned, ATF2 can be phosphorylated by p38MAPK, and this activation may lead to cell cycle inhibition.17,26 Because the suppression of proliferation was observed in the absence of Tbr2, we speculated that ATF2 was activated by an alternative pathway in the absence of activated p38MAPK during the early stages of wound healing. Immunohistochemistry indicated that ATF-2 was activated at 6 and 12 hours after epithelial debridement, despite the delayed p38MAPK activation (Fig. 4B). These results suggest the presence of an alternative pathway or pathways responsible for the activation of ATF2 aside from p38MAPK, which is likely independent of TGF-β signaling. We hypothesized that the stress-activated MAPK, JNK, may account for the activation of ATF2 for the suppression of epithelial cell proliferation at the early stages of corneal epithelial wound healing.

Inhibition of JNK Abolishes ATF2 Activation and Lifts the Suppression of Cell Proliferation

To address our hypothesis that JNK accounts for the activation of ATF2 in the absence of TGF-β signaling, leading to the suppression of cell proliferation at the wound edge, a JNK peptide inhibitor was administered to the eyes after epithelial debridement. Inhibition of JNK resulted in the absence of ATF2 activation and an increase in cell proliferation as the cell cycle suppression was lifted (Fig. 4C).

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that corneal epithelial wound healing is significantly delayed in mice lacking TGF-β signaling by the conditional ablation of Tbr2 (Fig. 2). This defect in wound healing is likely the result of delayed activation of p38MAPK. Despite the delayed activation of p38MAPK, there is still cell cycle suppression at the wound edge after injury (Figs. 3B, 4A). This is true even though corneal epithelial cell proliferation is increased in the uninjured eye of Tbr2ceΔ/ceΔ mice (Fig. 3B). We also showed that in the absence of TGF-β signaling, there is suppression in the expansion of actin stress fibers at the migrating edge (Fig. 3A). During corneal epithelial wound healing, the p38MAPK pathway is activated, leading to the activation of ATF2 and the subsequent suppression of cell proliferation at the leading edge of the wound. Interestingly, ATF2 is activated and, hence, proliferation is still suppressed in the absence of TGF-β signaling, suggesting that another pathway is capable of activating ATF2. We showed that this secondary pathway was mediated by JNK. Through the use of a JNK peptide inhibitor, we were able to inhibit ATF2 activation, thereby lifting cell cycle suppression (Figs. 4B, 4C). The antiproliferative effect of JNK1/2 has also been seen in human corneal epithelial cells after modification of dual specificity phosphatases.27 Although our study demonstrated the significance of the TGF-β and MAPK signaling pathways and the activation of JNK, it is unclear whether the TGF-β pathway and the JNK pathway are independent.

Dimerization of ATF2 with members of the AP-1 complex is likely a key step in the early stages of wound healing that is necessary for the suppression of cell proliferation at the leading edge. It has been demonstrated that epithelial debridement activates the AP-1 transcription factor and enhances the expression of c-Jun28 in addition to activating p38MAPK.13 We previously demonstrated that the inhibition of p38MAPK by SB202190 blocked epithelial cell migration but lifted the suppression of cell proliferation at the wound edge.13 Interestingly, in our transgenic mouse model system, the delayed activation of p38MAPK resulted in impaired cell migration but did not lift the suppression of cell proliferation, as in the previous study, because the activation of ATF2 was achieved by an alternative pathway, namely JNK. This original observation can be explained, in part, by the nonspecific effects of chemical inhibitors on signaling pathways.29

As mentioned, corneal epithelial wound healing is a complex, multistep process that includes both proliferation and migration. Although we show that in the absence of TGF-β signaling the suppression of proliferation at the wound edge is maintained through the activation of ATF2 by JNK, wound healing is still delayed because of impaired cell migration that results from the delayed activation of p38MAPK. In the mouse, the delay in wound healing does not seem to have a significant impact on long-term vision loss. The consequence of slowed migration and delayed wound healing in humans, however, could be much more severe. Such delay may to lead to exacerbation of the previous injury and to increased chance of infection and inflammation, which could contribute to long-term vision loss. It has been reported that p38MAPK, which is an important pathway activated by TGF-β receptors, is essential for corneal epithelial cell migration after epithelial debridement. It has recently been demonstrated that integrin β1 mediates p38MAPK activation and epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) by TGF-β2.30 EMT is characterized by increased cell mobility and the expression of mesenchymal cell markers (e.g., vimentin, α-smooth muscle actin, or both) by epithelial cell types and is associated with loss of cell polarity and cell-cell adherens junction.31–33 This may explain, in part, the mechanism leading to the suppression of cell migration during epithelial wound healing in mice lacking TGF-β signaling. The importance of p38MAPK function for proper corneal wound healing is evident, but no known ocular disease or disorder is directly linked to aberrant p38MAPK activation.

Our previous data suggest that healing of epithelial debridement is mediated through the p38MAPK pathway, which is activated 2 hours after injury, and not through the canonical TGF-β/Smad pathway. Although Smad activation occurs within minutes, this pathway is ultimately inhibited through the upregulation of Smad7.13 In the absence of Tbr2, Smad activation is prevented and p38MAPK activation is delayed for 48 hours. Thus, under normal conditions, the initial canonical TGF-β/Smad activation is essential for p38MAPK activation. The delayed activation of p38MAPK suggests the possibility that the p38MAPK cascade from TGF-β receptor signal transduction is suppressed completely and is activated later through another signaling cascade. Activin, epidermal growth factor (EGF), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), among others, are potential candidates for the late activation of p38MAPK in the absence of TGF-β signaling. Whatever the case may be, these data highlight the importance of TGF-β signaling and p38MAPK activation to promote epithelial migration during corneal epithelial wound healing.

Footnotes

Supported in part supported by National Institutes of Health/National Eye Institute Grant EY013755, Research to Prevent Blindness, and Ohio Lions Eye Research Foundation.

Disclosure: K. Terai, None; M.K. Call, None; H. Liu, None; S. Saika, None; C.-Y. Liu, None; Y. Hayashi, None; T.-I. Chikama, None; J. Zhang, None; N. Terai, None; C.W.-C. Kao, None; W.W.-Y. Kao, None

References

- 1. Cui W, Fowlis DJ, Cousins FM, et al. Concerted action of TGF-beta 1 and its type II receptor in control of epidermal homeostasis in transgenic mice. Genes Dev. 1995;9:945–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Joyce NC, Zieske JD. Transforming growth factor-beta receptor expression in human cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:1922–1928 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li DQ, Tseng SC. Three patterns of cytokine expression potentially involved in epithelial-fibroblast interactions of human ocular surface. J Cell Physiol. 1995;163:61–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McLennan IS, Koishi K. Cellular localisation of transforming growth factor-beta 2 and -beta 3 (TGF-beta2, TGF-beta3) in damaged and regenerating skeletal muscles. Dev Dyn. 1997;208:278–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mita T, Yamashita H, Kaji Y, et al. Effects of transforming growth factor beta on corneal epithelial and stromal cell function in a rat wound healing model after excimer laser keratectomy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1998;236:834–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nishida K, Sotozono C, Adachi W, Yamamoto S, Yokoi N, Kinoshita S. Transforming growth factor-beta 1, -beta 2 and -beta 3 mRNA expression in human cornea. Curr Eye Res. 1995;14:235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pelton RW, Saxena B, Jones M, Moses HL, Gold LI. Immunohistochemical localization of TGF beta 1, TGF beta 2, and TGF beta 3 in the mouse embryo: expression patterns suggest multiple roles during embryonic development. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1091–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilson SE, Schultz GS, Chegini N, Weng J, He YG. Epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor alpha, transforming growth factor beta, acidic fibroblast growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, and interleukin-1 proteins in the cornea. Exp Eye Res. 1994;59:63–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhao M, Agius-Fernandez A, Forrester JV, McCaig CD. Orientation and directed migration of cultured corneal epithelial cells in small electric fields are serum dependent. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1405–1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zieske JD, Hutcheon AEK, Guo X, Chung EH, Joyce NC. TGF-β receptor types I and II are differentially expressed during corneal epithelial wound repair. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1465–1471 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saika S. TGFbeta pathobiology in the eye. Lab Invest. 2006;86:106–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Massague J, Blain SW, Lo RS. TGFbeta signaling in growth control, cancer, and heritable disorders. Cell. 2000;103:295–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saika S, Okada Y, Miyamoto T, et al. Role of p38 MAP kinase in regulation of cell migration and proliferation in healing corneal epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:100–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gupta S, Campbell D, Derijard B, Davis RJ. Transcription factor ATF2 regulation by the JNK signal transduction pathway. Science. 1995;267:389–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Dam H, Wilhelm D, Herr I, Steffen A, Herrlich P, Angel P. ATF-2 is preferentially activated by stress-activated protein kinases to mediate c-jun induction in response to genotoxic agents. EMBO J. 1995;14:1798–1811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bhoumik A, Lopez-Bergami P, Ronai Z. ATF2 on the double-activating transcription factor and DNA damage response protein. Pigment Cell Res. 2007;20:498–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crowe DL, Shemirani B. The transcription factor ATF-2 inhibits extracellular signal regulated kinase expression and proliferation of human cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:2945–2949 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim SJ, Onwuta US, Lee YI, Li R, Botchan MR, Robbins PD. The retinoblastoma gene product regulates Sp1-mediated transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2455–2463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bhoumik A, Fichtman B, DeRossi C, et al. Suppressor role of activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2) in skin cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008:0706057105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bhoumik A, Takahashi S, Breitweiser W, Shiloh Y, Jones N, Ronai Z. ATM-dependent phosphorylation of ATF2 is required for the DNA damage response. Mol Cell. 2005;18:577–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chytil A, Magnuson MA, Wright CV, Moses HL. Conditional inactivation of the TGF-beta type II receptor using Cre:Lox. Genesis. 2002;32:73–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weng DY, Zhang Y, Hayashi Y, et al. Promiscuous recombination of LoxP alleles during gametogenesis in cornea cre driver mice. Mol Vis. 2008;14:562–571 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hayashi Y, Call M, Liu CY, et al. Monoallelic expression of Krt12 gene during corneal-type epithelium differentiation of limbal stem cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:4562–4568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saika S, Shiraishi A, Saika S, et al. Role of lumican in the corneal epithelium during wound healing. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2607–2612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Joseph H, Gorska AE, Sohn P, Moses HL, Serra R. Overexpression of a kinase-deficient transforming growth factor-beta type II receptor in mouse mammary stroma results in increased epithelial branching. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:1221–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bhoumik A, Gangi L, Ronai Z. Inhibition of melanoma growth and metastasis by ATF2-derived peptides. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8222–8230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang Z, Reinach PS, Zhang F, et al. DUSP5 and DUSP6 modulate corneal epithelial cell proliferation. Mol Vis. 2010;16:1696–1704 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Okada Y, Saika S, Hashizume N, et al. Expression of fos family and jun family proto-oncogenes during corneal epithelial wound healing. Curr Eye Res. 1996;15:824–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem J. 2000;351:95–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bhowmick NA, Zent R, Ghiassi M, McDonnell M, Moses HL. Integrin β1 signaling is necessary for transforming growth factor-β activation of p38MAPK and epithelial plasticity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46707–46713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bindels S, Mestdagt M, Vandewalle C, et al. Regulation of vimentin by SIP1 in human epithelial breast tumor cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:4975–4985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li Y, Yang J, Dai C, Wu C, Liu Y. Role for integrin-linked kinase in mediating tubular epithelial to mesenchymal transition and renal interstitial fibrogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:503–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Masszi A, Fan L, Rosivall L, et al. Integrity of cell-cell contacts is a critical regulator of TGF-beta 1-induced epithelial-to-myofibroblast transition: role for beta-catenin. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1955–1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]