Abstract

Cognition and emotion interact to determine ongoing behaviors. In this study, we investigated the interaction between cognition and emotion during response inhibition using the stop-signal task. In Experiment 1, low-threat stop-signals comprising fearful and happy face pictures were employed. We found that both fearful and happy faces improved response inhibition relative to neutral ones. In Experiment 2, we employed high-threat emotional stimuli as stop signals, namely stimuli previously paired with mild shock. In this case, inhibitory performance was impaired relative to a neutral condition. We interpret these findings in terms of the impact of emotional stimuli on early sensory/attentional processing, which resulted in improved performance (Experiment 1), and in terms of their impact at more central stages, which impaired performance (Experiment 2). Taken together, our findings demonstrate that emotion can either enhance or impair cognitive performance depending on the emotional potency of the stimuli involved.

Introduction

Cognition and emotion jointly contribute to ongoing behaviors. A large body of data has documented the many ways in which emotion affects cognitive function. Interestingly, both enhancement and impairment of cognition by emotion have been observed, properties that are particularly well described in the case of attention. For instance, affective significance enhances visual processing, acting as an attention-like process (Pessoa, 2010; Phelps, Ling, & Carrasco, 2006; Vuilleumier, 2005). In contrast, emotional content impairs performance in a vast array of situations. For example, determining the orientation of a target visual stimulus was slowed down following emotional pictures (Hartikainen, Ogawa, & Knight, 2000), and the presence of a central unpleasant picture increased response time when participants discriminated peripheral target letters (Tipples & Sharma, 2000), or the orientation of bars (Erthal et al., 2005).

Less is known about the impact of emotion on other cognitive functions, especially concerning the circumstances when they might enhance or impair performance. Recently, we have proposed a dual competition framework that describes cognitive-emotional interactions, such that emotional content influences both perceptual and executive control competition processes (Pessoa, 2009). The impact of emotion on cognition was hypothesized to depend on the intensity level of the emotional information. Stimuli of mild intensity were proposed to enhance sensory representation and thereby improve behavioral performance when task relevant. In contrast, high-arousal stimuli (e.g., threat of shock, erotica) were proposed to generally impair task performance, as they would consume processing resources that are shared with cognition – and required for task execution. In the present study, we investigated interactions between emotion and response inhibition and, in particular, sought to evaluate some of the predictions of the dual competition model. Response inhibition, the ability to suppress actions that are no longer behaviorally relevant or contextually appropriate, is a key function of the human executive control system and has been investigated behaviorally with both go/no-go tasks and stop-signal tasks. The latter paradigm is particularly appealing, as it provides an assessment of the time course of inhibitory processes, which can only be assessed indirectly (Logan & Cowan, 1984). In Experiment 1, we evaluated the impact of emotional, though low-intensity stimuli (faces) on response-inhibition performance. In Experiment 2, we evaluated the impact of stronger emotional stimuli (paired with mild shock) on response-inhibition performance.

Experiment 1

Methods

Subjects

Thirty-six volunteers participated in the study (18 females; 18–27 years old), which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Indiana University, Bloomington. All subjects were in good health, free of medications, and had no history of psychiatric or neurological disease. All subjects gave informed written consent. Three subjects' data (two male and one female) were removed from the analysis due to technical issues during data collection, and one additional male subject's data was removed due to extremely poor behavioral performance on go trials (76% correct compared to typical values exceeding 90%).

Anxiety questionnaires

After providing the consent to participate in the study, subjects filled the state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI) (Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, 1970).

Stimuli and task

We employed a stop-signal task as our paradigm of response inhibition (Figure 1). We used a simple choice reaction time (RT) task, which included both go and stop trials. Each go trial started with the presentation of a simple shape stimulus (1000 ms duration), and subjects were asked to indicate circle or square via a key-press using their right hand. On each trial, the visual shape stimulus stayed on the screen for 1000 ms independent of the subjects' response and was followed by a blank screen for 1000 ms. Stop trials were identical to go trials, except that a brief picture of a face (500 ms duration) was shown inside the shape stimulus after a variable stop-signal delay (SSD) relative to the onset of the go stimulus, which indicated that subjects should withhold their response. We used three different emotional stop signals in this study: neutral, happy, and fearful faces. The initial value of the SSD was set to 250 ms for all three stop conditions. The SSD was adjusted dynamically throughout the experiment, such that if subjects successfully inhibited their response on a stop trial, the SSD was increased by 50 ms on a subsequent stop trial, and if they failed to inhibit their response, the SSD was reduced by 50 ms on a subsequent stop trial (Logan, Schachar, & Tannock, 1997). This staircasing was done separately for each condition in order to ensure successful inhibition on approximately 50% of the stop trials in each condition. Subjects were instructed to respond as quickly and accurately as possible and were asked to inhibit their response upon viewing a face that followed the initial shape stimulus. They were also told that sometimes it might not be possible to successfully inhibit their response and that, in such cases, they should simply continue performing the task. Overall, the importance of going and stopping was stressed equally. Subjects performed a short practice run (approximately two minutes) before the main experiment runs to familiarize themselves with the task. In this training run, we used a separate set of neutral faces as stop signals.

Figure 1.

Stop-signal task paradigm for Experiment 1. During go trials, subjects responded to the go signal (circle or square?), whereas during stop trials, they were instructed to withhold motor response (signaled by a face picture, which could be neutral, fearful or happy). The stop signal followed the go stimulus after a variable-length delay, the stop signal delay (SSD), which was updated based on a staircase procedure (separately for each stop-signal condition) that maintained behavioral performance at approximately 50% correct.

Each subject performed six runs of the task. Each run contained a total of 150 trials, out of which there were 120 go trials (80%) and 30 stop trials (20%; 10 for each of the three stop conditions). Any given two stop trials had at least one go trial between them. The trial order was randomized but fixed across subjects. Within each run, go and stop trials contained circle and square shape stimuli in equal proportion, and the three stop conditions contained an equal number of circle and square shape stimuli. As stop signals, 180 face pictures (30 male and 30 female identities with three expressions) were selected from the Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces (KDEF) (Lundqvist, Flykt, & Öhman, 1998), the Ekman set (Ekman & Friesen, 1976), the Ishai-NIMH set (Ishai, Pessoa, Bikle, & Ungerleider, 2004), and the Nimstim Face Stimulus Set (MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Early Experience and Brain Development).

Data analysis

As stated above, the SSD was adjusted dynamically to yield an inhibition success rate of approximately 50%. The stop-signal reaction time (SSRT), which provides an estimate of the “inhibitory reaction time”, was calculated for each stop signal condition by subtracting the average SSD from the median RT during correct go trials, following the race model (Logan & Cowan, 1984). Following the procedure of Logan et al. (1997), we used the untrimmed go RT distribution for SSRT estimation so that the tracking algorithm would cover the whole distribution of go responses. But while reporting the median go RT for correct trials, we removed subject-specific outliers based on three standard deviations away from the mean. As the main objective of this experiment was to compare the inhibitory performance across three emotional stop signal conditions, we ran a one-way repeated measures ANOVA on SSRT values using stop signal type (neutral, happy, or fearful) as the within-subjects factor. Likewise, we also ran separate one-way repeated measures ANOVAs on inhibition rate and stop-respond RT (i.e., unsuccessful stop trials [UNSUCC], namely stop trials during which subjects failed to inhibit the response).

Results

Behavioral results are summarized in Table 1. Mean reaction time on correct go trials was 611 ms and mean go error rate was 4.8%. As expected, because of the staircasing procedure, stop performance was approximately 50% correct during all three conditions (neutral: 54.3%; happy: 54.3%; fearful: 54.0%) and no main effect of emotion was observed in the repeated-measures ANOVA analysis [F(2, 31) = 0.41, p = 0.67]. Importantly, the ANOVA analysis based on SSRT revealed a main effect of emotion [F(2, 31) = 6.31, p < 0.005, η2 = 0.17], demonstrating that the emotionality of the stop signal had a significant effect on inhibitory performance. Follow-up simple paired t-tests revealed that SSRT was significantly lower in both fearful (214.8 ms) and happy (220.0 ms) conditions relative to neutral (232.0 ms) ones (fearful: t(31) = 4.66, p < 0.001; happy: t(31) = 2.17, p < 0.05), which show that subjects were better in inhibiting the responses with fearful and happy stop signals relative to neutral ones. There was no significant difference in SSRT between the happy and fearful conditions [t(31) = 0.95, p = 0.35], suggesting that the arousal component of the faces interacted with inhibitory processes rather than the valence component. Finally, for the three conditions, the reaction times of stop-respond (UNSUCC) trials were faster than those of correct go trials (neutral: t(31) = 8.20, p < 0.001; happy: t(31) = 8.61, p < 0.001; fearful: t(31) = 9.54, p < 0.001) as predicted by the race model (Logan & Cowan, 1984), and no effect of emotion was observed on stop-respond RT [F(2, 31) = 0.64, p = 0.53].

Table 1.

Behavioral results from Experiment 1

| Go RT (ms)a | 611.3 ± 17.6 |

| Go error rate (%) | 4.8 ± 0.5 |

| Neutral | Happy | Fearful | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition rate (%) | 54.3 ± 0.4 | 54.3 ± 0.5 | 54.0 ± 0.4 |

| SSD (ms) | 379.7 ± 20.4 | 391.7 ± 18.9 | 396.8 ± 20.7 |

| SSRT (ms) | 232.0 ± 6.9 | 220.0 ± 5.8 | 214.8 ± 6.7 |

| UNSUCC RT (ms) | 559.3 ± 18.7 | 553.0 ± 17.9 | 552.4 ± 18.1 |

SSD: stop-signal delay; SSRT: stop-signal reaction time; UNSUCC: unsuccessful stop trial.

Value reported is the mean of individual median RTs.

To investigate the relationship between anxiety scores and changes in inhibitory performance, we ran a correlation analysis between subjects' anxiety scores (state and trait, separately) and SSRT values (differences between neutral and fearful conditions). We observed a significant correlation between trait anxiety scores and SSRT differences [r(31) = 0.36, p < 0.05; Figure 2], such that subjects with higher trait anxiety showed larger inhibitory performance improvements during the fearful (relative to neutral) condition. No significant correlation was observed between state anxiety scores and SSRT differences (r(31) = 0.09, p = 0.61).

Figure 2.

Correlation between anxiety scores and behavioral performance in Experiment 1. Across participants, we observed a significant linear relationship between trait anxiety scores and SSRT differences indicating that participants with higher trait anxiety scores showed greater inhibitory performance improvement during the fear-face (relative to neutral) condition.

Experiment 2

Methods

Subjects

Twenty-two volunteers (15 females; 18–27 years old) participated in the study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Indiana University, Bloomington. All subjects were in good health, free of medications, and had no history of psychiatric or neurological disease. All subjects gave informed written consent. Two subjects' (one male and one female) data were removed from the analysis due to unusually poor performance on stop trials (0% inhibitory rate).

Anxiety questionnaires

After providing consent to participate in the study, 17 out of 20 subjects filled the state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI) (Spielberger et al., 1970).

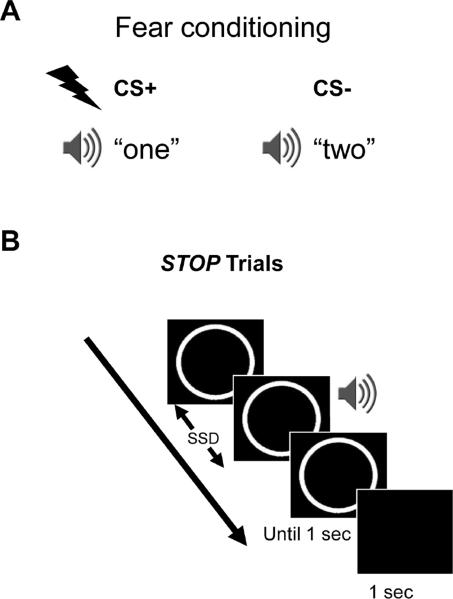

Fear conditioning procedure

Each subject's experimental session began with a fear conditioning component during which subjects passively listened to two possible tones (spoken word “one” or “two”, 350 ms duration) from the external speakers connected to the experimental computer (Figure 3A). One of the two tones was paired with shock (50% contingency; CS+), whereas the other tone was never paired with shock (CS−). The tones assigned to CS+ and CS− conditions were counterbalanced across subjects.

Figure 3.

(A) Fear conditioning procedure in Experiment 2. Subjects passively listened to two possible words (spoken word “one” or “two”). One of the words was paired with shock (50% contingency; CS+), whereas the other was never paired with shock (CS−). (B) Stop-signal task paradigm in Experiment 2. During go trials (not shown here), subjects responded to the go signal (circle or square?), whereas during stop trials, they were instructed to withhold motor response (signaled by the auditory stimulus, “one” or “two”). The stop signal followed the go stimulus after a variable-length delay, the stop signal delay (SSD), which was updated based on a staircase procedure (separately for each stop-signal condition) that maintained behavioral performance at approximately 50% correct.

Each trial during conditioning was 10-s long and started with a small green fixation cross shown for 500 ms at the center of the screen. Then one of the two tones (randomized across trials) was played (the CS+ tone was followed by an unconditioned stimulus with 50% probability). As an unconditioned stimulus (US), a 500-ms electric shock (50 Hz) was delivered to the distal phalanges of the third and fourth fingers of the left hand by a shock stimulator (E13ȃ22; Coulbourn Instruments). Before the experiment, subjects were instructed of the contingency rule (i.e., CS+ tone), but were not informed about the probability of US delivery. The intensity of electric shock, which ranged between 0.8 and 4.0 mA, was determined separately for each subject so as to be “highly unpleasant but not painful”. During conditioning, skin conductance responses (SCRs) were recorded from a subset of subjects (N = 7) with the MP-150 system (BIOPAC Systems) and Ag/AgCl electrodes placed on the distal phalanges of the index and middle finger of the left hand. SCR was amplified and sampled at 250 Hz.

To avoid extinction, conditioning and stop-signal task “runs” (see below) alternated, beginning with a conditioning run. No shocks were administered during the stop-signal task runs. The initial conditioning run consisted of 30 trials (10 CS−; 10 CS+ and 10 CS+ with shock), while the remaining conditioning runs were slightly shorter in duration with 18 trials each (6 CS−; 6 CS+ and 6 CS+ with shock).

Stimuli and stop-signal task

We used the same stop-signal task as in Experiment 1 except that auditory tones (“one” and “two”) were used as stop signals (Figure 3B). As described above, one of these tones (counterbalanced across subjects) was paired with shock during the conditioning runs (CS+ stop signal) while the other tone was never paired with shock (CS− stop signal). Similar to Experiment 1, SSD values were adjusted dynamically throughout the experiment based on separate staircases for CS+ and CS− stop-signal conditions. Each subject performed five runs of the stop-signal task. Each run contained a total of 100 trials, out of which there were 76 go trials and 24 stop trials (12 for each of the two stop conditions). Other randomization procedures were implemented as in Experiment 1.

Data analysis: skin conductance responses

The analysis of SCR waveforms was conducted using MATLAB. SCR data were first linearly detrended and then on each trial, the level of SCR was calculated by subtracting a baseline (average signal between 0 and 1s) from the peak amplitude during the 4–6 s time window after stimulus onset (Lim, Padmala, & Pessoa, 2009; Prokasy & Raskin, 1974). Mean SCR responses between CS− and CS+ trials were compared using a paired t-test.

Data analysis: stop-signal task

Similar methods as in Experiment 1 were used to analyze the behavioral data from stop-signal task runs. In this experiment, we used paired t-tests to compare the differences between behavioral indices from CS+ and CS− stop-signal conditions.

Results

During the conditioning runs, mean SCR responses during the CS− and CS+ trials was 0.12 μS and 0.34 μS respectively and the difference between CS− and CS+ SCR responses was significant [t(6) = 5.29; p < 0.01] (note that SCR data was available for 7 participants only).

Behavioral results from the stop-signal task runs are summarized in Table 2. Mean reaction time on correct go trials was 693 ms and mean go error rate was 4.6%. As expected, because of the staircasing procedure, stop performance was approximately 50% correct during both CS− and CS+ conditions (CS−: 54.8%; CS+: 53.7%) and no difference was observed between the CS− and CS+ conditions [t(19) = 1.12, p = 0.28]. Critically, SSRT was longer during the CS+ condition (214.8 ms) compared to the CS− condition (197.3 ms) [t(19) = 2.23, p < 0.05, Cohen's d = 0.50], demonstrating that it was harder to inhibit the behavioral response during the former condition. Finally, during both conditions, the reaction times of UNSUCC trials were faster than those of correct go trials (CS−: t(19) = 7.76, p < 0.001; CS+: t(19) = 7.60, p < 0.001), in line with predictions of the race model (Logan & Cowan, 1984). Also, the difference between CS− and CS+ UNSUCC trials was marginally significant [t(19) = 2.04, p = 0.06]. Finally, no significant correlation was observed between state or trait anxiety and differential SSRT (difference between CS+ and CS− conditions) (state anxiety: r(16) = 0.04, p = 0.87; trait anxiety: r(16) = 0.05, p = 0.84).

Table 2.

Behavioral results from Experiment 2

| Go RT (ms)a | 692.8 ± 21.0 |

| Go error rate (%) | 4.6 ± 0.9 |

| CS− | CS+ | |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibition rate (%) | 54.8 ± 0.5 | 53.7 ± 0.9 |

| SSD (ms) | 495.4 ± 21.4 | 477.9 ± 21.0 |

| SSRT (ms) | 197.3 ± 7.5 | 214.8 ± 8.8 |

| UNSUCC RT (ms) | 645.5 ± 22.9 | 633.1± 21.3 |

SSD: stop-signal delay; SSRT: stop-signal reaction time; UNSUCC: unsuccessful stop trial.

Value reported is the mean of individual median RTs.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated cognitive-emotional interactions by probing how emotional stimuli affected response inhibition. Whereas fearful- and happy-face stop signals enhanced inhibitory performance, a conditioned stimulus impaired inhibitory processes.

In Experiment 1, both fearful and happy expressions decreased the stop-signal reaction time relative to neutral faces. Although inhibition was numerically faster for fearful vs. happy faces, no significant difference was detected between these conditions, consistent with the notion that arousal, but not valence, played the central role in the effect. Although Experiment 1 does not allow us to determine the precise mechanisms that subserve the observed behavioral effect, we offer the following interpretation. Response inhibition is thought to rely on several regions of frontal cortex, as well as subcortical sites, which are believed to be explicitly involved in response inhibition (Aron, 2007; Chambers, Garavan, & Bellgrove, 2009; Li, Huang, Constable, & Sinha, 2006). More generally, however, successful performance during the stop-signal task is behaviorally challenging and depends on several processes, including perceptual processing and attention, in addition to inhibitory mechanisms per se. Consistent with this notion, a recent MEG study revealed that fluctuations of sensory processing linked to both go and stop stimuli have an impact on inhibitory performance during a stop-signal task (Boehler et al., 2009). Specifically, enhanced processing of the go stimulus facilitated movement (i.e., go) responses, whereas enhanced processing of the stop signal facilitated inhibition, possibly because the processing of go and stop signals share processing resources. In the context of Experiment 1, we suggest that, relative to neutral faces, emotional faces generated enhanced sensory representations of the stop stimulus in visual cortex, which is consistent with a large literature (Pessoa, Kastner, & Ungerleider, 2002; Vuilleumier, 2005), leading to a stronger representation of the stop signal and consequently better stopping performance. This scenario is also consistent with findings that parietal cortex, which is involved in several important attentional functions, plays an important role in response inhibition (Garavan, Ross, & Stein, 1999; Liddle, Kiehl, & Smith, 2001; Padmala & Pessoa, 2010). In other words, enhanced sensory representation and/or attentional processing may have facilitated stop-signal processing when these were emotional faces and hence improved inhibitory performance. Although we favor a more perceptual interpretation of the findings of Experiment 1, it is also possible that more central mechanisms were at play. For instance, Goldstein et al. (2007) reported cognitive-emotional interactions in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during a go/no-go task (although the absence of corresponding behavioral findings makes it harder to interpret the neuroimaging findings).

In Experiment 2, the emotional stop signal impaired task performance, namely it increased the stop-signal reaction time. An important framework proposes that emotion is organized around two motivational systems, one appetitive and one defensive. The defense system is primarily activated in contexts involving threat and it has been suggested that its activation produces freezing behavior in rats (Lang et al., 2000) and freezing-like behavior in humans (Facchinetti et al., 2006). According to this framework, in the context of Experiment 2, it would be predicted that a stop signal previously paired with shock would likely facilitate inhibitory processes. Our results revealed, instead, that a high-intensity stop signal impaired inhibition. As suggested in the dual competition framework, we interpret the findings of Experiment 2 as indicative that the processing of the threat stimulus, which was paired with mild electrical stimulation during the conditioning phases, consumed processing resources that were needed for successful inhibitory performance. This interpretation is consistent with a previous study of emotional stimulus interference on response inhibition (Verbruggen & De Houwer, 2007). In that study, task-irrelevant emotional or neutral stimuli were presented at the beginning of the trial, specifically prior to the go stimulus itself. Both response and stopping latencies were increased by emotional stimuli (both words and pictures were employed), regardless of their valence. Although the results of Experiment 2 are similar to those of the study by Verbruggen and De Howver, in our study the stop signal itself was emotional. Accordingly, because the processing of emotional stimuli is thought to be potentiated relative to neutral ones, an emotional stop signal actually may have improved stopping performance, contrary to what was observed here. Indeed, in Experiment 1 emotional faces employed as stop stimuli did improve inhibitory performance. The fact that the more potent conditioned stimuli of Experiment 2 impaired response inhibition, suggests that whatever potential benefits of emotion on sensory processing and attention (as suggested in the context of Experiment 1) were outweighed by the deleterious effect of threat. We thus suggest that threat consumed more central processing resources required by inhibition, along the lines suggested by the dual competition framework. Although speculative, we would predict that high-intensity positive stop stimuli would impair inhibitory performance in an analogous manner (although creating sufficiently high intensity positive stimuli in a laboratory setting may prove challenging).

In this study, we manipulated the emotional content of stop signals. It would also be valuable to manipulate the affective significance of go signals. In this scenario, we would expect that response inhibition would be poorer during emotional go trials compared to neutral ones. For example, in the case of a low-intensity stimulus, enhanced perceptual processing of the go stimulus (relative to neutral) would leave fewer perceptual resources for the stop process. This idea is again consistent with the data reported by Boehler et al., 2009, who showed that response inhibition was compromised on trials with enhanced go signal processing.

In conclusion, we investigated the effect of emotional content on response inhibition by employing stimuli low in threat (emotional faces; Experiment 1) and more potent stimuli (stimuli paired with shock; Experiment 2). Whereas stop signals involving emotional faces improved stopping performance, conditioned stimuli impaired it. We interpret the current findings in terms of the impact of the emotional stimuli in early sensory/attentional processing, which result in improved performance in Experiment 1, and in terms of their impact at more central stages, which impaired performance in Experiment 2. Taken together, our findings demonstrate that emotion can either enhance or impair cognitive performance, likely as a function of the emotional potency of the stimuli involved. It should be emphasized however that, according to our interpretation, the impact of emotion on inhibition did not reflect a simple inverted-U shaped impact of emotional content on a particular stopping mechanism. Rather, stop signals of different intensities may impact separable mechanisms contributing to observed behavior.

Acknowledgements

Support for this work was provided in part by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH071589) to L.P.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/emo

References

- Aron AR. The neural basis of inhibition in cognitive control. Neuroscientist. 2007;13(3):214–228. doi: 10.1177/1073858407299288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehler CN, Munte TF, Krebs RM, Heinze HJ, Schoenfeld MA, Hopf JM. Sensory MEG Responses Predict Successful and Failed Inhibition in a Stop-Signal Task. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(1):134–145. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers CD, Garavan H, Bellgrove MA. Insights into the neural basis of response inhibition from cognitive and clinical neuroscience. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33(5):631–646. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Friesen WV. Pictures of facial affect. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Facchinetti LD, Imbiriba LA, Azevedo TM, Vargas CD, Volchan E. Postural modulation induced by pictures depicting prosocial or dangerous contexts. Neuroscience Letters. 2006;410:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garavan H, Ross TJ, Stein EA. Right Hemispheric Dominance of Inhibitory Control: An Event-Related Functional MRI Study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(14):8301–8306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein M, Brendel G, Tuescher O, Pan H, Epstein J, Beutel M, Yang Y, Thomas K, Levy K, Silverman M, Clarkin J, Posner M, Kernberg O, Stern E, Silbersweig D. Neural substrates of the interaction of emotional stimulus processing and motor inhibitory control: an emotional linguistic go/no-go fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2007;36:1026–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishai A, Pessoa L, Bikle PC, Ungerleider LG. Repetition suppression of faces is modulated by emotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9827–9832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403559101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Davis M, Ohman A. Fear and anxiety: Animal models and human cognitive psychophysiology. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2000;61:137–159. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00343-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CS, Huang C, Constable RT, Sinha R. Imaging response inhibition in a stop-signal task: neural correlates independent of signal monitoring and post-response processing. J Neurosci. 2006;26(1):186–192. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3741-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle PF, Kiehl KA, Smith AM. Event-related fMRI study of response inhibition. Hum Brain Mapp. 2001;12(2):100–109. doi: 10.1002/1097-0193(200102)12:2<100::AID-HBM1007>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SL, Padmala S, Pessoa L. Segregating the significant from the mundane on a moment-to-moment basis via direct and indirect amygdala contributions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(39):16841–16846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904551106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan GD, Cowan WB. On the ability to inhibit thought and action: A theory of an act of control. Psych Rev. 1984;91:295–327. [Google Scholar]

- Logan GD, Schachar RJ, Tannock R. Impulsivity and inhibitory control. Psychological Science. 1997;8(1):60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Padmala S, Pessoa L. Moment-to-moment fluctuations in fMRI amplitude and interregion coupling are predictive of inhibitory performance. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2010;10(2):279–297. doi: 10.3758/CABN.10.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa L. How do emotion and motivation direct executive function? Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13(4):160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa L. Emotion and cognition and the amygdala: From “what is it?” to “what's to be done?”. Neuropsychologia. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.06.038. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa L, Kastner S, Ungerleider LG. Attentional control of the processing of neutral and emotional stimuli. Cognitive Brain Research. 2002;15(1):31–45. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(02)00214-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA, Ling S, Carrasco M. Emotion facilitates perception and potentiates the perceptual benefits of attention. Psychol Sci. 2006;17(4):292–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokasy WF, Raskin DC. Electrodermal activity in psychological research. Academic Press; New York: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen F, De Houwer J. Do emotional stimuli interfere with response inhibition? Evidence from the stop signal paradigm. Cognition and Emotion. 2007;21(2):391–403. [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier P. How brains beware: neural mechanisms of emotional attention. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9(12):585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]