Abstract

A strong cellular crosstalk exists between the pathogen Helicobacter pylori and high-output NO production. However, how NO and H. pylori interact to signal in gastric epithelial cells and modulate the innate immune response is unknown. We show that chemical or cellular sources of NO induce the anti-inflammatory effector heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) in gastric epithelial cells through a pathway that requires NF-κB. However, H. pylori decreases NO-induced NF-κB activation, thereby inhibiting HO-1 expression. This inhibitory effect of H. pylori results from activation of the transcription factor heat shock factor-1 by the H. pylori virulence factor CagA and by the host signaling molecules ERK1/2 and JNK. Consistent with these findings, HO-1 is downregulated in gastric epithelial cells of patients infected with cagA+, but not cagA− H. pylori. Enhancement of HO-1 activity in infected cells or in H. pylori-infected mice inhibits chemokine generation and reduces inflammation. These data define a mechanism by which H. pylori favors its own pathogenesis by inhibiting HO-1 induction through the action of CagA.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori exclusively colonizes the human stomach and causes chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and gastric adenocarcinoma (1). H. pylori expresses virulence factors implicated in colonization, resistance to the acidic conditions of the stomach, and pathogenesis. Among them, the protein cytotoxin associated gene A (CagA) plays a pivotal role in the etiology of H. pylori-associated gastric diseases (2, 3). Upon attachment to gastric epithelial cells, H. pylori uses a type IV secretion system (T4SS) to inject CagA into the cytoplasm of host cells (4). CagA is then phosphorylated on tyrosine residues by the host Src and c-Abl kinase families (5). Phosphorylated CagA (p-CagA) induces morphological transformation in gastric epithelial cells characterized by elongated cell shape with cytoskeletal rearrangements and increased motility (6), and also participates in the activation of the innate immune response of these cells (7–9). In addition, unphosphorylated CagA can also induce signaling in host cells and thus modulates cellular functions that include epithelial proliferation (9) and apoptosis (10). The combination of these cellular events mediated by CagA may increase the risk for carcinogenesis.

Innate immune function during H. pylori infection is mainly mediated by the MAPK enzyme family and the transcription factor NF-κB (7, 11). The activation of these signaling pathways leads to transcription of inducible genes encoding effectors of innate immunity, including cytokines and chemokines; among them, IL-8 is one of the most effective mediators of H. pylori immunopathogenesis since it recruits neutrophils to the mucosa of infected tissues. H. pylori infection also results in a mixed Th1/Th17-dominant T cell response (12, 13). These activated immune cells contribute to the establishment of chronic inflammation of the stomach (13, 14). However, these vigorous innate and adaptive responses fail to eradicate H. pylori; the persistence of the bacterium and the associated inflammation in the human stomach are major causal factors in gastric carcinogenesis. The failure of specific immunity can be in part due to increased Treg response during H. pylori infection (15), but other pathways are also involved (1). Since the innate immune response is linked to the development of adaptive responses, it is crucial to identify mechanisms by which H. pylori interacts with gastric epithelial cells and thus modulates their immune function.

NO is a signaling molecule with potent immunomodulatory capabilities, and we have directly implicated it as an important host defense component in H. pylori infection. Despite the induction of expression of the enzyme inducible NO synthase (iNOS), H. pylori inhibits NO synthesis by limiting L-arginine availability and by suppressing iNOS translation through the formation of polyamines (16–19). Restoration of high-output NO production by gastric macrophages results in attenuation of gastritis in H. pylori-infected mice (17). However, the cellular mechanism of this anti-inflammatory effect induced by NO remains unknown. It has been described that NO is a potent inducer of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), an enzyme that possesses numerous anti-inflammatory properties (20). We thus reasoned that NO and H. pylori may modulate HO-1 in gastric epithelial cells.

We demonstrate herein that H. pylori inhibits the NO-dependent induction of HO-1 in gastric epithelial cells by a process mediated by CagA. This occurs through activation of the transcription factor heat shock factor-1 (HSF1) that suppresses NO-induced NF-κB activation and transcription of hmox-1, the gene that encodes HO-1. Induction of HO-1 in gastric epithelial cells prior to H. pylori infection markedly attenuates IL-8 synthesis by human gastric epithelial cells in vitro, and reduces inflammation in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

The NO donors NOR4 (±-(E)-ethyl-2-[(E)-hydroxyimino]-5-nitro-3-hexenecarbamoylpyridine; 100 μM) and DEA-NONOate (diethylammonium (Z)-1-(N,N-diethylamino)diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate; 100 μM), and the iNOS inhibitor 1400W (N-(3-aminomethyl)benzylacetamidine; 5 μM) were purchased from Alexis Biochemicals. The carbon monoxide (CO) donor tricarbonyldichlororuthenium-(II)-dimer (CORM2) and the HO-1 inhibitor zinc protoporphyrin IX (ZnPP) were obtained from Sigma. The second HO-1 inhibitor chromium mesoporphyrin (CrMP) that we used in vivo was purchased from Frontier Scientific. The following pharmacological compounds were obtained from Calbiochem: the NF-κB inhibitor Bay11–7082 ((E)3-[(4-methylphenyl)sulfonyl]-2-propenenitrile; 10 μM); the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (2′-amino-3′-methoxyflavone; 10 μM); the ERK1/2 inhibitor ERKi (3-(2-aminoethyl)-5-((4-ethoxyphenyl)methylene)-2,4-thiazolidinedione, HCl; 20 μM); the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (anthra[1,9-cd]pyrazol-6(2H)-one, 1,9-pyrazoloanthrone; 1 μM); the p38 inhibitor SB203580 (4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-methylsulfinylphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl)1H-imidazole; 2 μM); the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one; 10 μM); the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF1) inhibitor HIFi (3-(2-(4-adamantan-1-yl-phenoxy)-acetylamino)-4-hydroxybenzoic acid methyl ester; 10 μM); and the Src inhibitor PP1 (4-amino-5-(4-methylphenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo-d-3,4-pyrimidine).

Bacteria

We used the cagA+ H. pylori strains 60190, 7.13, and PMSS1. The following isogenic mutants were also used as described: cagE, cagA, vacA, and flaA of the strain 60190 (21), cagA, and vacA in the strain 7.13 (22), and cagE in the strain PMSS1 (23). The ureA mutant was constructed in H. pylori 60190 by deletion of the gene and insertion of a chloramphenicol resistance cassette as described (24). Bacteria grown on blood agar plates overnight were used to infect cells.

Human subjects

Biopsies from gastric tissues were obtained as described (22, 25) under two protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board at Vanderbilt University. The cagA status of H. pylori was determined from these tissues by PCR analysis performed on isolated colonies (26–27). Histologic grading of gastritis was performed by a gastrointestinal pathologist (M.B.P.) who was blinded to the clinical status of the subjects. We used a scale of 0–3 for both acute inflammation and chronic inflammation, resulting in a total score of 0–6. Frozen tissues were utilized for RNA analysis and paraffin-embedded tissues were used for immunohistochemistry.

Animals and experimental design

Mice in this study were used under protocol M/05/176 approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Vanderbilt University. HO-1 was induced and inhibited in the stomach of C57BL/6 male mice (The Jackson Laboratory) by i.p. injection of hemin and CrMP, respectively (28). Mice were treated with hemin 4 and 2 days before infection with H pylori PMSS1 (5 × 108 CFU/mouse), a strain that retains its ability to translocate CagA in vivo (23). CrMP was injected the day of the infection and every other day post-infection. Mice were sacrificed two days post-inoculation with H. pylori.

Cells and transfections

The human gastric epithelial cell line AGS, the mouse conditionally-immortalized stomach cells ImSt, and the murine macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 were maintained and used as described (29, 30). Cells were stimulated with H. pylori at a multiplicity of infection of 10. All pharmacological inhibitors of signaling pathways were added 30 min prior to activation.

AGS cells in Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Media (Invitrogen) were transfected with i) 100 nM ON-TARGETplus siRNAs (Dharmacon) directed against hsf1, hmox-1, or lmnA (the gene encoding lamin A, used as a control) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), ii) 100 nM SignalSilence siRNAs (Cell Signaling) directed against p38, SAPK/JNK, or ERK1/2 using Lipofectamine 2000, iii) 0.5 μg pNF-κB-Luc plasmid, an inducible reporter plasmid containing the luciferase gene driven by an NF-κB promoter element, or the pCIS-CK negative control plasmid (Agilent Technologies) using Lipofectamine 2000, amd/or iv) 2 μg pSP65SRα plasmid vector expressing or not wild-type full-length cagA (pWT-cagA) or phospho-resistant cagA (pPR-cagA) using Lipofectamine LTX and Plus Reagent. After 6 h, cells were washed, maintained 24–36 h in fresh medium, and then stimulated.

mRNA analysis

RNA purification and real-time PCR were performed as described (31). Primers are listed in Supplemental Table I.

Western blots

For the p-CagA immunoblots, AGS cells were lysed in Tris-HCl 50 mM, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS, the Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Set III, Calbiochem), and the Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Set I, Calbiochem); lysates were then sonicated. For all the other Western blots, nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins were extracted/separated using the NE-PER Nuclear Protein Extraction Kit (Pierce). Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA Protein Assay (Pierce). Western blots were performed using 30 μg of protein per lane for the p-CagA blots and 10 μg for all the others. Primary and secondary Abs are listed in Supplemental Table II.

The purity of the nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts was verified by Western blotting. Lamin A, a specific nuclear protein, was detected only in the nuclear fraction and was completely absent in the cytoplasmic fraction, and inversely, the cytoplasmic enzyme glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was present only in the cytoplasmic fraction (data not shown).

Determination of chemokine concentration

IL-8 and KC concentrations were determined in culture supernatants using DuoSet ELISA kits (R&D Systems).

Luciferase activity assay

AGS cells were lysed in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors and luciferase activity was determined using the Luciferase Assay System kit (Promega). Luminosity was measured in a Synergy 4 microplate reader (BioTek).

HO-1 immunostaining and scoring system

Immunostaining was performed on human and murine gastric tissues as described (17) using a rabbit polyclonal anti-human/mouse HO-1 Ab (1:600; StressGen). Slides were reviewed and scored by a GI pathologist (M.B.P.) who was blinded to the clinical status of the subjects, or the treatment conditions of the mice. HO-1 immunostaining intensity was graded on a scale of 0 (absent), 1 (weak), 2 (moderate), or 3 (strong) as described (32). The percentages of epithelial cells staining at each intensity level was multiplied by the intensity score, resulting in a scoring range of 0–300.

Statistical analysis

All the data represent the mean ± SEM. Student’s t test or ANOVA with the Newman-Keuls test were used to determine significant differences between two groups or to analyze significant differences among multiple test groups, respectively. For all the figures, *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, and ***, p < 0.001. The relationship between HO-1 levels and histological scores was determined using Pearson’s correlation test.

Results

H. pylori inhibits NO-stimulated HO-1 expression in gastric epithelial cells through a mechanism that requires CagA

The expression of hmox-1, the gene that encodes HO-1, was first analyzed in AGS cells treated with the NO donor NOR4 and/or infected with H. pylori strain 60190. The levels of hmox-1 mRNA were significantly increased in human AGS cells treated with NOR4, whereas H. pylori alone had no effect (Fig. 1A). Further, when H. pylori and NO were added simultaneously to the cells, hmox-1 transcripts were decreased in comparison with cells treated with NOR4 alone (Fig. 1A). Induction of hmox-1 mRNA by NO and inhibition by H. pylori also occurred with ImSt cells infected with strain 7.13 (Fig. 1B), a co-culture system that we have well-characterized. Similar results also occurred when another NO donor, DEA-NONOate, was used in AGS cells (Supplemental Fig. 1). HO-1 protein levels increased in a time-dependent manner in AGS cells after NO stimulation (Fig. 1C). At each time point tested, there was less HO-1 protein expression when cells treated with NOR4 were also infected with H. pylori (Figs. 1C and 1D). Further, when compared to uninfected cells, a decrease in HO-1 protein level was observed in cells exposed to H. pylori alone for 18 h (Figs. 1C and 1D). In contrast, the mRNA and protein levels of HO-2 did not change with exposure of cells to NOR4 or H. pylori (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of NO and H. pylori on HO-1 induction in gastric epithelial cells. A and B, hmox-1 mRNA expression. AGS (A) or Imst (B) cells were treated with NOR4 and/or infected for 6 h with H. pylori (Hp) strain 60190 or 7.13, respectively. RNA was purified, reverse transcribed, and the expression of hmox-1 was analyzed by real-time PCR; n = 5. C, The presence of the HO-1 and β-actin proteins was detected by Western blotting in cellular extract of AGS cells stimulated for 6, 12, or 18 h with NOR4 and/or H. pylori. Representative data of 3 independent experiments. D, Densitometric analysis of Fig. 1C; n = 3.

We then sought to identify the H. pylori factor(s) involved in the inhibition of hmox-1 mRNA expression in NO-treated AGS cells. Wild-type (WT) H. pylori or vacA, ureA or flaA mutant strains inhibited hmox-1 mRNA expression by 70–90% (Fig. 2A); however, this inhibitory effect was substantially lost when either a cagA mutant or a cagE mutant, which fails to translocate CagA, was used (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the NO-induced expression of hmox-1 mRNA was effectively inhibited by either WT or phospho-resistant CagA when compared to the pSP65SRα plasmid vector (Fig. 2B). Accordingly, we found that the Src kinase inhibitor PP1, which effectively decreased CagA phosphorylation in AGS cells (Fig. 2C), had no effect on the inhibition of hmox-1 expression by H. pylori (Fig. 2D). Moreover, the concentrations of PP1 that we used were not toxic for the cells (data not shown). These data indicate that a functional T4SS and the native effector CagA are required to inhibit NO-induced hmox-1 gene transcription.

FIGURE 2.

Inhibition of NO-induced hmox-1 expression by H. pylori requires CagA. A, Expression of hmox-1 in AGS cells stimulated with NOR4, and infected or not with WT H. pylori or various mutant strains. Values obtained for infected cells treated with NOR4 were compared to cells treated with NOR4 alone; n = 3. B, Expression of hmox-1 in AGS cells transfected with pSP65SRα plasmid vector, pWT-cagA, or pPR-cagA, and treated with NOR4. Values obtained for transfected cells treated with NOR4 were compared to cells not transfected and treated with NOR4; n = 3. C and D, Effect of the Src inhibitor PP1. AGS cells were treated with PP1 for 30 min prior to stimulation with NOR4 ± H. pylori for 6 h. CagA phosphorylation was assessed by Western blot using the PY99 Ab (C). Expression of hmox-1 mRNA was assessed by real-time PCR; values obtained for infected cells treated with NOR4 were compared to cells treated with NOR4 alone (D); n = 3. E, Expression of hmox-1 in Imst cells stimulated with NOR4, and infected or not with H. pylori 7.13 or PMSS1 or with the corresponding mutant strains. Values obtained for infected cells treated with NOR4 were compared to cells treated with NOR4 alone; n = 3.

The role of CagA was then confirmed in Imst cells. The inhibition of NO-induced hmox-1 expression by H. pylori 7.13 or by the vacA mutant was lost when the cagA mutant was used (Fig. 2E). Similarly, the strain PMSS1, but not the cagE mutant, inhibited the NO-induced hmox-1 expression (Fig. 2E).

Human infection with cagA+ H. pylori results in decreased HO-1 levels in gastric epithelial cells

To demonstrate the in vivo relevance of our findings, we analyzed the expression of HO-1 in gastric tissues of patients in which the cagA+ or cagA− status of the infecting H. pylori strains was known. The levels of hmox-1 transcripts in patients infected with cagA+ strains were significantly decreased when compared to normal gastric tissues or to subjects infected with cagA− H. pylori (Fig. 3A). We then evaluated the cellular localization of HO-1 protein by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3B). In uninfected patients, HO-1 expression was abundant in gastric epithelial cells of the glandular necks and the deeper regions of the glands. Tissues from subjects infected with cagA+ H. pylori strains exhibited less staining in epithelial cells when compared to tissues from controls or persons infected with cagA− strains (Figs. 3B and 3C).

FIGURE 3.

HO-1 levels are decreased in patients infected with cagA+ H. pylori. A, Expression of hmox-1 in gastric tissues with histologically normal mucosa and from subjects infected with cagA+ or cagA− strains of H. pylori; n = 8 cases per group. B, Representative HO-1 immunoperoxidase staining in gastric tissues. C, Quantification of staining score for HO-1 in gastric epithelium on a 0–300 scale; n = 10 cases per group. D, HO-1 staining and histologic gastritis scores were plotted for each patient. The linear regression line, the correlation coefficient (r), and the p value are shown.

When gastric inflammation was graded in the same tissues, there was significantly more histologic gastritis in patients infected with the cagA+ strains (4.9 ± 0.3) than in those with the cagA− strains (3.3 ± 0.3; p < 0.01). Further, we found that in gastric biopsies of H. pylori-infected patients increased HO-1 levels correlated significantly with decreased gastritis (Fig. 3D).

Induction of HO-1 by NO requires NF-κB, and the inhibition of HO-1 by H. pylori is mediated by ERK1/2, JNK, and HSF1

We next determined the molecular mechanisms by which NO stimulates hmox-1 mRNA expression and H. pylori suppresses this expression. We first used a pharmacological approach to inhibit various signaling pathways and transcription factors that may modulate transcription of hmox-1. As shown in Fig. 4A (left panel), inhibitors of NF-κB (Bay11–7082) or PI3K (LY294002) significantly reduced hmox-1 mRNA expression in AGS cells treated with NO. In contrast, the increased levels of hmox-1 transcripts with NO treatment were maintained when all the other inhibitors were used (right panel). Moreover, the downregulatory effect of H. pylori on NO-stimulated hmox-1 expression was lost when inhibitors of MEK (PD98059), ERK1/2 (ERKi), or JNK (SP600125) were added to the cells, whereas the inhibitors of p38 (SB203580), or HIF1 had no significant effect (Fig. 4A; right panel); cell viability was not affected by the use of these pharmacologic inhibitors (data not shown). Similarly, the inhibitory effect of H. pylori on hmox-1 induction was lost in cells transfected with ERK1/2 or JNK siRNAs, but not with siRNAs for p38 or lmnA, as shown in Fig. 4B. These data suggest that hmox-1 mRNA expression induced by NO requires PI3K and NF-κB, and that H. pylori suppresses this induction through ERK1/2 and JNK.

FIGURE 4.

Regulation of hmox-1 transcription by NO and H. pylori. A, Pharmacological inhibition of signaling pathways. AGS cells were pretreated with Bay11–7082 (Bay), LY294002 (LY), PD98059 (PD), ERKi, SP600125 (SP), SB203580 (SB), or HIFi 30 min prior to adding NOR4 ± H. pylori for 6 h. Expression of hmox-1 mRNA was analyzed by real-time PCR; n = 5. B, MAPK silencing. AGS cells transfected with lmnA, ERK1/2, JNK or p38 siRNAs were treated with NOR4 ± H. pylori. Expression of hmox-1 was performed by real-time PCR; n = 3.

The transcription factor HSF1 may modulate the transcription of various genes encoding heat shock proteins, such as hmox-1. Because a specific pharmacologic inhibitor of HSF1 does not exist, we transfected AGS cells with siRNAs for hsf1 or lmnA (used as control). The H. pylori-mediated inhibition of NO-induced hmox-1 transcription (Fig. 5A) and HO-1 protein expression (Fig. 5B) was completely abrogated by hsf1 siRNA, while the lmnA siRNA had no effect, demonstrating that H. pylori inhibits the induction of HO-1 through HSF1. Additionally, the enhancement of expression of hmox-1 in AGS cells treated with NOR4 and H. pylori that occurred with knockdown of HSF1 was inhibited by 89.7 ± 0.3% with the NF-κB inhibitor Bay 11–7082 (Fig. 5C). These data demonstrate that the HSF1-dependent downregulation of hmox-1 expression occurs through the inhibition of NO-induced NF-κB activation.

FIGURE 5.

H. pylori-induced HSF1 dowregulates hmox-1 expression. AGS cells were transfected with siRNAs directed against hsf1 or lmnA and then treated with NOR4 and/or H. pylori. The levels of hmox-1 mRNA (A; 6 h) and HO-1 protein (B; 18 h) were assessed by real-time PCR and Western blotting, respectively; n = 4 for (A), and (B) is the representative data of 3 independent experiments. C, AGS cells, transfected with hsf1 or lmnA siRNAs, were treated for 6 h with NOR4 ± H. pylori, with or without the NF-κB inhibitor Bay 11–7082 (Bay). The level of hmox-1 transcripts was analyzed by real-time PCR; n = 4.

Activation of HSF1 by H. pylori is mediated by CagA, ERK1/2 and JNK

It has been reported that the activation of human HSF1 requires the phosphorylation of Ser326 (33). Consistent with our findings that implicate HSF1 in the negative regulation of hmox-1 by H. pylori, HSF1 phosphorylation on Ser326 was observed in AGS cells infected with H. pylori for 30 min, and this persisted for a 2 h period; this was not altered by NOR4 (Fig. 6A). Other studies have revealed that phosphorylation of HSF1 on a serine at position 303 represses its transcriptional activity (34). However, we found that HSF1 was not phosphorylated at Ser303 in AGS cells infected with H. pylori and/or treated with NOR4 (data not shown).

FIGURE 6.

H. pylori activates HSF1. A, Immunodetection of p-HSF1 on Ser326 and total HSF1 in AGS cells exposed to NOR4 and/or H. pylori. B, AGS cells pretreated with ERKi, SP600125 (SP), or SB203580 (SB) were then infected with H. pylori for 1 h; HSF1 phosphorylation was analyzed by Western blotting. C, HSF1 phosphorylation in AGS cells infected for 1 h with H. pylori 60190 WT or with each mutant strain. D, Densitometric analysis of Fig. 6C; n = 3. E, Levels of p-HSF1(Ser326) in cells transfected with pSP65SRα, pWT-cagA, or pPR-cagA.

Because we found that ERK1/2, JNK, and HSF1 mediate the inhibition of hmox-1 transcription by H. pylori, we reasoned that the signaling kinases ERK1/2 and JNK might favor HSF1 phosphorylation on Ser326. As shown in Fig. 6B, there was a marked decrease of p-HSF1-Ser326 in H. pylori-infected cells pretreated with ERKi or SP600125 when compared to infected cells without any inhibitor. Consistent with our findings that the p38 inhibitor SB203580 had no effect on hmox-1 mRNA levels (see Fig. 4A), it failed to alter phosphorylation of HSF1 (Fig. 6B).

Since the inhibition of NO-induced hmox-1 expression by H. pylori requires CagA, we determined the involvement of this virulence factor in HSF1 phosphorylation. HSF1 was significantly less phosphorylated at Ser326 when cells were stimulated with the cagA mutant compared to infection with the WT, vacA−, ureA− or flaA− strains (Fig. 6C and 6D). In addition, HSF1 phosphorylation occurred in AGS cells transfected with either pWT-cagA or pPR-cagA, whereas the plasmid vector alone had no effect (Fig. 6D).

H. pylori-induced HSF1 leads to a reduction of NO-induced NF-κB activation

We found that NO induces hmox-1 through a NF-κB-dependent pathway and that HSF1 downregulates hmox-1 expression; we thus determined whether HSF1 effectively inhibits NF-κB activation. We first analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 7A) the accumulation of p-p65-Ser536 in the nucleus and the phosphorylation of IκBα on Ser32/36 in the cytoplasm of AGS cells. There was increased phosphorylation of p65 and IκBα in cells with knockdown of lmnA followed by infection with H. pylori for 0.5 h, with or without NOR4; at this time point, knockdown of hsf1 had no additional effect. At a later time point (3 h), in cells transfected with lmnA, NF-κB activation by H. pylori was attenuated, but was activated by NOR4. Importantly, there was a marked reduction of p-p65 and pIκBα accumulation in cells treated with NOR4 when they were also infected with H. pylori. In contrast, knockdown of HSF1 resulted in sustained NF-κB activation at the 3 h time point in H. pylori-infected cells, as well as in cells treated with NOR4 and infected with H. pylori. Lastly, hsf1 siRNA had no effect on NF-κB activation by NOR4 alone. At both time points, similar results were obtained in cells transfected with lmnA siRNA and in non-transfected cells (data not shown).

FIGURE 7.

H. pylori-induced HSF1 decreases NF-κB activation. AGS cells knockdown for lamin A or HSF1 were treated with NOR4 and/or infected with H. pylori. A, Nuclear p-p65 and cytoplasmic p-IκBα (3 h) were analyzed by Western blotting. B, NF-κB activity was determined in cells expressing the pNF-κB-Luc plasmid; n = 3.

We then assessed NF-κB activity directly in AGS cells using a reporter plasmid. NF-κB activity was rapidly and transiently increased after H. pylori infection in AGS cells transfected with lmnA siRNA (Fig. 7B). In the lmnA siRNA-transfected cells, NO-induced NF-κB activation was observed after 1 h and was then enhanced at 2 h; this increase was eliminated in NO-treated cells infected with H. pylori. However, knockdown of HSF1 resulted in sustained NF-κB activation in H. pylori-infected cells at 1 h and 2 h post-infection, and the inhibition of NF-κB activity by H. pylori in NO-treated cells was no longer observed.

Taken together, the latter results indicate that the induction of NF-κB by H. pylori in gastric epithelial cells is actually suboptimal and is negatively regulated by HSF1. Moreover, the inhibition of NO-induced NF-κB activation by H. pylori is mediated by HSF1.

HO-1 suppresses chemokine production by H. pylori-infected gastric epithelial cells

We then analyzed the role of HO-1 in the innate immune function elicited by H. pylori in gastric epithelial cells. We first stimulated cells for 18 h with NOR4 to induce HO-1, and then infected them with H. pylori, in the presence or absence of the HO-1 inhibitor ZnPP. As expected, H. pylori induced IL-8 mRNA expression and IL-8 secretion in AGS cells (Figs. 8A and 8B, respectively). When infected cells were pretreated with NOR4, and thus express HO-1, we found a significant decrease in the levels of IL-8 mRNA and protein, and this inhibition was abolished when ZnPP was added to these cells (Figs. 8A and 8B). Pretreatment with NOR4 and/or treatment with ZnPP had no effect on IL-8 induction in uninfected cells. To further verify the ability of HO-1 to inhibit H. pylori-stimulated IL-8 generation, we used a siRNA approach. AGS cells were first transfected with siRNA directed against hmox-1 or lmnA, pretreated with NO for 18 h, and then infected or not with H. pylori. The inhibitory effect of NOR4 pretreatment on H. pylori-induced IL-8 gene expression was eliminated using hmox-1 siRNA, but not lmnA siRNA (Fig. 8C).

FIGURE 8.

HO-1 inhibits H. pylori-induced IL-8 generation. A and B, IL-8 mRNA expression (A) and [IL-8] in the culture supernatant (B) of AGS cells pretreated or not with NOR4 and then infected with H. pylori, in the presence or absence of ZnPP; n = 4. C, Same conditions as in (A) with cells transfected or not with hmox-1 or lmnA siRNAs; n = 4. D, IL-8 mRNA expression determined in cells infected with H. pylori ± CORM2 or bilirubin; n = 3.

Because HO-1 converts heme into CO and bilirubin, we next ascertained the effect of these products on IL-8 expression in AGS cells. The CO donor CORM2 was capable of significantly inhibiting H. pylori-stimulated IL-8 mRNA levels with a concentration as low as 1 μM, whereas bilirubin had no significant effect (Fig. 8D). Both compounds had no significant effect on IL-8 mRNA expression in uninfected cells (data not shown).

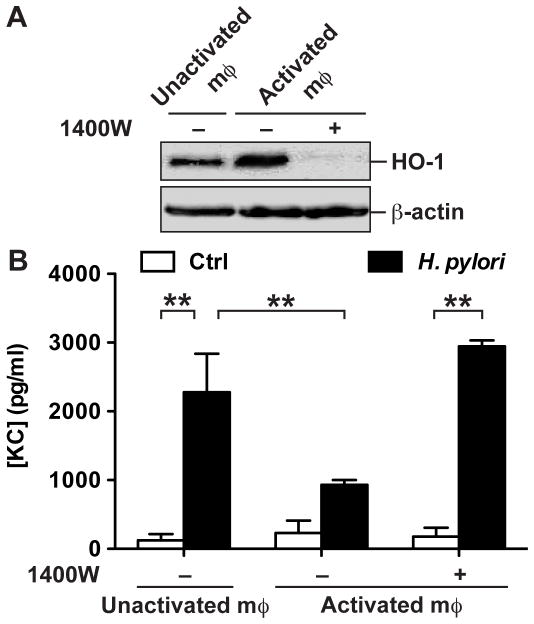

We then determined the role of NO generated by cells on HO-1 induction and H. pylori-induced chemokine synthesis by gastric epithelial cells. We used a model in which ImSt cells in 0.2 μM filter supports were cocultured for 18 h with RAW 264.7 macrophages that were pretreated or not with IFN-γ to stimulate NO production. There was an increase in HO-1 protein levels in ImSt cells cultured with activated macrophages compared to ImSt cells cultured with unactivated macrophages (Fig. 9A); when the iNOS inhibitor 1400W was added to the coculture of ImSt cells with IFN-γ-treated RAW 264.7 macrophages, HO-1 was no longer induced (Fig. 9A). After coculture, ImSt cells were removed, washed, and infected with H. pylori. There was significantly less production of the neutrophil chemoattractant KC (also known as CXCL1) by H. pylori-infected ImSt cells expressing HO-1 due to being previously cocultured with activated macrophages, compared to ImSt cells cocultured with unactivated RAW 264.7 cells or with activated macrophages treated with 1400W (Fig. 9B).

FIGURE 9.

Cellular source of NO induces HO-1 and inhibit chemokine release by epithelial cells. A, RAW264.7 macrophages (mφ) were cultured on plates and stimulated or not with IFN-γ for 24 h, washed and exposed to ImSt cells cultured above on 0.2 μm filter supports, in the presence or absence of 5 μM 1400W. After 18 h, HO-1 and β-actin protein levels were analyzed by Western blotting in ImSt cells; data are representative of 2 independent experiments. B, ImSt cells cocultured with macrophages as in A, were then separated from macrophages and infected or not (Ctrl) for 3 h with H. pylori; KC concentrations were measured in the culture supernatants; n = 3.

Induction of HO-1 in the stomach leads to a reduction of host immune response to H. pylori

Because H. pylori inhibits HO-1 expression and HO-1 activity decreases IL-8/KC release by infected epithelial cells, we hypothesized that increasing HO-1 expression in the gastric mucosa could downregulate H. pylori-induced innate immune activation. We observed an increase of hmox-1 mRNA (Fig. 10A) and HO-1 protein (Fig. 10B) levels in mice treated with hemin when compared to untreated animals. The HO-1 staining localized strongly to the gastric epithelium and this was absent in tissues incubated with an isotype IgG control (Fig. 10B). The induction of hmox-1 mRNA and HO-1 protein by hemin remained in the presence of H. pylori or CrMP (Figs. 10A and 10B). The levels of H. pylori colonization were not significantly modulated by the hemin or CrMP treatments (Supplemental Fig. 2). It has been demonstrated that the infiltration of PMN cells peaks at 2 days post-inoculation with H. pylori in mice (35). Consistent with this, we detected a significant increase in expression of the chemokine KC (Fig. 10C) and in the number of PMN cells (Fig. 10D) in the antral mucosa of H. pylori-infected mice at this time point. These increases were abolished in animals treated with hemin and thus expressing HO-1, but these benefits of hemin treatment were lost in mice receiving CrMP (Figs. 10C and 10D). Treatment of infected mice with CrMP alone had no significant effect on KC expression and PMN recruitment. Taken together, these data suggest that the level of HO-1 in H. pylori-infected mice is not sufficient to regulate inflammation, and that under conditions of experimentally enhanced HO-1 expression, acute gastritis is significantly attenuated.

FIGURE 10.

Induction of HO-1 by hemin decreases acute inflammation in H. pylori-infected mice. Expression of hmox-1 mRNA (A) and HO-1 staining (B) in the stomach of mice treated or not with hemin ± CrMP and infected with H. pylori PMSS1. Levels of KC mRNA expression (C), and number of PMN cells in an antral section (D); n = 5–8 per group.

Discussion

The molecular crosstalk that occurs between H. pylori and gastric epithelial cells is critical for the pathogenesis of the infection, given that these cells are the first in contact with the bacteria, and play an important role in the development of the immune and inflammatory responses as well as carcinogenesis. In this context, our work has identified a novel mechanism by which H. pylori hijacks the signal transduction of the gastric epithelium and favors its own immunopathogenicity. As shown in Fig. 11, we have demonstrated that NO signals through NF-κB in gastric epithelial cells to stimulate the synthesis of HO-1 that inhibits the H. pylori-elicited production of IL-8; however, H. pylori activates HSF1 that inhibits NO-induced NF-κB activation and hmox-1 expression.

FIGURE 11.

A model for the regulation of expression and the role of HO-1 in H. pylori infection. HO-1 induction in gastric epithelial cells by NO requires NF-κB (a); when HO-1 is expressed in the cells, it blocks IL-8 mRNA expression induced by H. pylori (b). However, the bacterium activates HSF1 through CagA/ERK1/2- and JNK-dependent pathways (c), which inhibits NO-induced NF-κB and hmox-1 mRNA expression (d).

Therefore, we propose that H. pylori has developed a strategy to promote its own pathogenesis by inhibiting HO-1 induction. Our in vitro findings have direct significance in vivo since we have also shown that i) the levels of HO-1 in gastric epithelial cells are decreased in patients infected with cagA+ H. pylori, ii) the level of HO-1 expression is inversely correlated with the gastritis in infected patients, and iii) induction of HO-1 in cagA+ H. pylori-infected mice results in decreased acute gastritis as determined by KC mRNA expression and infiltration of PMN cells. It should be noted that there was no inhibition of hmox-1 expression in mice infected for 2 days; however, we have found that in mice infected for 4 months with H. pylori PMSS1, the levels of hmox-1 mRNA was significantly decreased by 62% (data not shown). Conversely, it has been reported that the amount of HO-1 protein is higher in H. pylori-positive patients than in controls when assessed by immunohistochemistry (36); however, the cagA status of the strains that infected these patients was not determined, and may account for the discrepancies between our data and the former study. Additionally, we have confirmed our findings with mRNA analysis, which was not performed in the previous study.

In the present study we analyzed the effect of NO on H. pylori-induced innate immune response of gastric epithelial cells. When cells were treated with NO donors, there was a strong induction of HO-1; importantly, this same induction was observed when cells were stimulated with NO released from activated macrophages, supporting the likelihood that this event can occur in the gastric niche where activated macrophages and epithelial cells are in very close proximity (37). We have demonstrated that gastric epithelial cells pretreated with NO and thus expressing HO-1 produce less IL-8 after H. pylori infection than cells not treated with NO, suggesting that NO may play an anti-inflammatory role in gastric tissue. Therefore, NO could be envisioned as a paracrine mediator produced by host gastric macrophages to limit the inflammatory response through the upregulation of HO-1 in epithelial cells. In this context, H. pylori could favor its own pathogenesis by limiting HO-1 induction by two strategies: first, the impairment of NO production by macrophages using its own arginase (16, 18) and the induction of host arginase II (19) and polyamine synthesis (17) that inhibit iNOS translation and second, the direct inhibition of NO-induced hmox-1 mRNA expression, as shown is this study.

Several transcription factors, including NF-κB and HSF1, have been implicated in the regulation of hmox-1 transcription depending on the type of cells and the nature of stimulus (38). We show herein that NF-κB is the main factor responsible for hmox-1 mRNA expression in gastric epithelial cells after stimulation with NO. Similar data has been obtained with human periodontal ligament cells (39) and in the cardiac tissue of transgenic mice expressing iNOS (40); in addition, NF-κB-dependent upregulation of the hmox-1 gene has been reported in human gastric carcinoma cells stimulated with heme or cadmium (41). It is notable that two NF-κB binding sites exist in the proximal promoter region of hmox-1 and are involved in the transcription of this gene (42).

In contrast to the finding that pathogenic Escherichia coli stimulates hmox-1 mRNA expression in enterocytes (31), we have now shown that H. pylori inhibits HO-1 induction in gastric epithelial cells through a mechanism that requires HSF1. We show that HSF1 is rapidly phosphorylated on Ser326 through a signaling cascade involving CagA translocation, ERK1/2, and JNK. Accordingly, it has been reported that non-phosphorylated CagA interacts with the growth factor receptor-binding protein-2 (43) or with the c-Met receptor (44), and inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor endocytosis thus favoring its abundance at the cell surface (45); together, these events may mediate the phosphorylation/activation of ERK1/2 (43, 46). However, it is not clear how H. pylori induces JNK activation; although the cag pathogenicity island is required for JNK activation (47, 48), CagA and the classical signaling pathways, including NOD1, Cdc42, Rac1, MKK4, and MKK7, are not involved (48, 49). Therefore, we speculate that HSF1 is activated by a mechanism that requires the T4SS and both CagA-mediated ERK1/2 activation and a JNK-dependent pathway (Fig. 11). The fact that HSF1 phosphorylation on Ser326 was not completely inhibited by the ERK1/2 or JNK inhibitors supports the concept that both pathways are required. Further, our findings that hmox-1 inhibition by H. pylori in gastric epithelial cells was not completely abrogated when a cagA-deficient strain was used, whereas the cagE mutant did not inhibit the transcription of hmox-1, suggest that other bacterial effectors injected by the T4SS are involved in the downregulation of HO-1. Moreover, HSF1 was not phosphorylated on Ser303, a residue implicated in the inactivation of HSF1; this result is consistent with the fact that H. pylori inhibits GSK3α (50), the kinase responsible for Ser303 phosphorylation (34).

We then demonstrated that H. pylori-activated HSF1 inhibited the transcription of hmox-1. Although two potential heat shock elements (HSE), HSE1 and HSE2, which can bind HSF1, are present in the promoter region of hmox-1, these regions are not functional in humans (38). This suggests that despite being activated by H. pylori, HSF1 cannot initiate the transcription of hmox-1. Further, it has been reported that HSF1 binding to HSE1 represses the hmox-1 expression in human Hep3B hepatoma cells (51). In parallel, we showed that activated HSF1 attenuates NF-κB activation. Similarly, it has been reported that heat induced-HSF1 blocks the DNA binding activity of NF-κB and suppresses the NF-κB-dependent transcription of TNF-α or iNOS in murine macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (52, 53). Although it is well established that H. pylori stimulates NF-κB activation, we now propose that this activation in gastric epithelial cells is transient and not maximal due to HSF1 activation. Together, these data demonstrate that H. pylori stimulates the activation of HSF1, which in turn inhibits NO-induced NF-κB activation and hmox-1 mRNA expression. HSF1 may also directly decrease the binding of NF-κB to the hmox-1 promoter region, since HSE1 overlaps with one of the κB consensus sequences (42).

Aside from its role in heme degradation, the anti-inflammatory role of HO-1 has been well documented in other diseases such as colitis (54). HO-1 has been implicated as a major immunomodulatory effector through i) inhibition of the innate immune response by disrupting MAPK, NF-κB, or STAT-1 signaling (31, 55); ii) limitation of Th1 cytokine synthesis (56); iii) suppression of T cell proliferation (57), including Th17 cells (58); and iv) enhancement of Treg function (59). Our studies strongly support the concept that the ability of a pathogenic bacterium to limit the expression of an anti-inflammatory enzyme such as HO-1 will enhance its pathogenesis. Accordingly, our results show that inducing HO-1 in the stomach of H. pylori-infected mice results in decreased KC mRNA expression and PMN cell infiltration, indicating less acute inflammation. Moreover, the correlation of the low levels of HO-1 with the high levels of gastritis in patients with cagA+ infection and the higher levels of HO-1 that correlated with lower levels of gastritis in cagA− patients suggests that modulation of HO-1 may represent an important link between the cagA status of H. pylori and the development of inflammation. Strategies to induce HO-1 may represent a novel therapeutic approach to limit the severity of gastritis without the need to target H. pylori, as a means to overcome the growing problem of antibiotic resistance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Alberto Delgado for his technical help in histology.

This work was supported by NIH Grants R01DK053620 and R01AT004821 (to K.T.W.), P01CA116087 (to R.M.P and K.T.W.), UL1RR024975 (Vanderbilt CTSA, KTW) and P01CA028842 (to P.C. and K.T.W.), by the Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Research Center Grant (P30DK058404), and by a Merit Review Grant from the Office of Medical Research, Department of Veterans Affairs (to K.T.W.). A.P.G. and T.S. are supported in part by the Philippe Foundation.

Abbreviations used in this article

- CagA

cytotoxin associated gene A

- CrMP

chromium mesoporphyrin

- HO-1

heme oxygenase-1

- HIF1

hypoxia-inducible factor-1

- HSE

heat shock element

- HSF1

heat shock factor-1

- iNOS

inducible NO synthase

- T4SS

type IV secretion system

- WT

wild-type

- ZnPP

zinc protoporphyrin IX

References

- 1.Peek RM, Jr, Fiske C, Wilson KT. Role of innate immunity in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric malignancy. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:831–858. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaser MJ, Perez-Perez GI, Kleanthous H, Cover TL, Peek RM, Chyou PH, Stemmermann GN, Nomura A. Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2111–2115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogura K, Maeda S, Nakao M, Watanabe T, Tada M, Kyutoku T, Yoshida H, Shiratori Y, Omata M. Virulence factors of Helicobacter pylori responsible for gastric diseases in Mongolian gerbil. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1601–1610. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odenbreit S, Puls J, Sedlmaier B, Gerland E, Fischer W, Haas R. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science. 2000;287:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selbach M, Moese S, Hauck CR, Meyer TF, Backert S. Src is the kinase of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6775–6778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Backert S, Moese S, Selbach M, Brinkmann V, Meyer TF. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 972 of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein is essential for induction of a scattering phenotype in gastric epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:631–644. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandt S, Kwok T, Hartig R, Konig W, Backert S. NF-kappaB activation and potentiation of proinflammatory responses by the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9300–9305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409873102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SY, Lee YC, Kim HK, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori CagA transfection of gastric epithelial cells induces interleukin-8. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:97–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki M, Mimuro H, Kiga K, Fukumatsu M, Ishijima N, Morikawa H, Nagai S, Koyasu S, Gilman RH, Kersulyte D, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA phosphorylation-independent function in epithelial proliferation and inflammation. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oldani A, Cormont M, Hofman V, Chiozzi V, Oregioni O, Canonici A, Sciullo A, Sommi P, Fabbri A, Ricci V, et al. Helicobacter pylori counteracts the apoptotic action of its VacA toxin by injecting the CagA protein into gastric epithelial cells. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000603. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schweitzer K, Sokolova O, Bozko PM, Naumann M. Helicobacter pylori induces NF-kappaB independent of CagA. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:10–11. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeLyria ES, Redline RW, Blanchard TG. Vaccination of mice against H. pylori induces a strong Th-17 response and immunity that is neutrophil dependent. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:247–256. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi Y, Liu XF, Zhuang Y, Zhang JY, Liu T, Yin Z, Wu C, Mao XH, Jia KR, Wang FJ, et al. Helicobacter pylori-induced Th17 responses modulate Th1 cell responses, benefit bacterial growth, and contribute to pathology in mice. J Immunol. 2010;184:5121–5129. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bamford KB, Fan X, Crowe SE, Leary JF, Gourley WK, Luthra GK, Brooks EG, Graham DY, Reyes VE, Ernst PB. Lymphocytes in the human gastric mucosa during Helicobacter pylori have a T helper cell 1 phenotype. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:482–492. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70531-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kao JY, Zhang M, Miller MJ, Mills JC, Wang B, Liu M, Eaton KA, Zou W, Berndt BE, Cole TS, et al. Helicobacter pylori immune escape is mediated by dendritic cell-induced Treg skewing and Th17 suppression in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1046–1054. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.11.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaturvedi R, Asim M, Lewis ND, Algood HM, Cover TL, Kim PY, Wilson KT. L-arginine availability regulates inducible nitric oxide synthase-dependent host defense against. Helicobacter pylori Infect Immun. 2007;75:4305–4315. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00578-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaturvedi R, Asim M, Hoge S, Lewis ND, Singh K, Barry DP, de Sablet T, Piazuelo MB, Sarvaria AR, Cheng Y, et al. Polyamines impair immunity to Helicobacter pylori by inhibiting L-arginine uptake required for nitric oxide production. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1686–1698. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gobert AP, McGee DJ, Akhtar M, Mendz GL, Newton JC, Cheng Y, Mobley HL, Wilson KT. Helicobacter pylori arginase inhibits nitric oxide production by eukaryotic cells: a strategy for bacterial survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13844–13849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241443798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis ND, Asim M, Barry DP, Singh K, de Sablet T, Boucher JL, Gobert AP, Chaturvedi R, Wilson KT. Arginase II restricts host defense to Helicobacter pylori by attenuating inducible nitric oxide synthase translation in macrophages. J Immunol. 2010;184:2572–2582. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryter SW, Alam J, Choi AM. Heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide: from basic science to therapeutic applications. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:583–650. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peek RM, Jr, Blaser MJ, Mays DJ, Forsyth MH, Cover TL, Song SY, Krishna U, Pietenpol JA. Helicobacter pylori strain-specific genotypes and modulation of the gastric epithelial cell cycle. Cancer Res. 1999;59:6124–6131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franco AT, Israel DA, Washington MK, Krishna U, Fox JG, Rogers AB, Neish AS, Collier-Hyams L, Perez-Perez GI, Hatakeyama M, et al. Activation of beta-catenin by carcinogenic Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10646–10651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504927102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnold I, Lee JY, Amieva MR, Roers A, Flavell RA, Sparwasser T, Muller A. Tolerance rather than immunity protects from Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric preneoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2010;140:199–209. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donahue JP, Israel DA, Peek RM, Blaser MJ, Miller GG. Overcoming the restriction barrier to plasmid transformation of Helicobacter pylori. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:1066–1074. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Correa P, Fontham ET, Bravo JC, Bravo LE, Ruiz B, Zarama G, Realpe JL, Malcom GT, Li D, Johnson WD, et al. Chemoprevention of gastric dysplasia: randomized trial of antioxidant supplements and anti- Helicobacter pylori therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1881–1888. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.23.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sicinschi LA, Correa P, Peek RM, Jr, Camargo MC, Delgado A, Piazuelo MB, Romero-Gallo J, Bravo LE, Schneider BG. Helicobacter pylori genotyping and sequencing using paraffin-embedded biopsies from residents of Colombian areas with contrasting gastric cancer risks. Helicobacter. 2008;13:135–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2008.00554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaturvedi R, Asim M, Romero-Gallo J, Barry DP, Hoge S, de Sablet T, Delgado AG, Wroblewski LE, Piazuelo MB, Yan F, et al. Spermine oxidase mediates the gastric cancer risk associated with Helicobacter pylori CagA. Gastroenterology. 2011 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi KM, Gibbons SJ, Nguyen TV, Stoltz GJ, Lurken MS, Ordog T, Szurszewski JH, Farrugia G. Heme oxygenase-1 protects interstitial cells of Cajal from oxidative stress and reverses diabetic gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:2055–2064. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu H, Chaturvedi R, Cheng Y, Bussiere FI, Asim M, Yao MD, Potosky D, Meltzer SJ, Rhee JG, Kim SS, et al. Spermine oxidation induced by Helicobacter pylori results in apoptosis and DNA damage: implications for gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8521–8525. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan F, Cao H, Chaturvedi R, Krishna U, Hobbs SS, Dempsey PJ, Peek RM, Jr, Cover TL, Washington MK, Wilson KT, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor activation protects gastric epithelial cells from Helicobacter pylori-induced apoptosis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1297–1307. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vareille M, Rannou F, Thelier N, Glasser AL, de Sablet T, Martin C, Gobert AP. Heme oxygenase-1 is a critical regulator of nitric oxide production in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli-infected human enterocytes. J Immunol. 2008;180:5720–5726. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong SK, Chaturvedi R, Piazuelo MB, Coburn LA, Williams CS, Delgado AG, Casero RA, Jr, Schwartz DA, Wilson KT. Increased expression and cellular localization of spermine oxidase in ulcerative colitis and relationship to disease activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1557–1566. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guettouche T, Boellmann F, Lane WS, Voellmy R. Analysis of phosphorylation of human heat shock factor 1 in cells experiencing a stress. BMC Biochem. 2005;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chu B, Soncin F, Price BD, Stevenson MA, Calderwood SK. Sequential phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase and glycogen synthase kinase 3 represses transcriptional activation by heat shock factor-1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30847–30857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Algood HM, Gallo-Romero J, Wilson KT, Peek RM, Jr, Cover TL. Host response to Helicobacter pylori infection before initiation of the adaptive immune response. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;51:577–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barton SG, Rampton DS, Winrow VR, Domizio P, Feakins RM. Expression of heat shock protein 32 (hemoxygenase-1) in the normal and inflamed human stomach and colon: an immunohistochemical study. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2003;8:329–334. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2003)008<0329:eohsph>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Necchi V, Candusso ME, Tava F, Luinetti O, Ventura U, Fiocca R, Ricci V, Solcia E. Intracellular, intercellular, and stromal invasion of gastric mucosa, preneoplastic lesions, and cancer by Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1009–1023. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alam J, Cook JL. How many transcription factors does it take to turn on the heme oxygenase-1 gene? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:166–174. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0340TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee SK, Choi HI, Yang YS, Jeong GS, Hwang JH, Lee SI, Kang KH, Cho JH, Chae JM, Kim YC, et al. Nitric oxide modulates osteoblastic differentiation with heme oxygenase-1 via the mitogen activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-kappaB pathways in human periodontal ligament cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32:1328–1334. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Q, Guo Y, Ou Q, Cui C, Wu WJ, Tan W, Zhu X, Lanceta LB, Sanganalmath SK, Dawn B, et al. Gene transfer of inducible nitric oxide synthase affords cardioprotection by upregulating heme oxygenase-1 via a nuclear factor-{kappa}B-dependent pathway. Circulation. 2009;120:1222–1230. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.778688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu ZM, Chen GG, Ng EK, Leung WK, Sung JJ, Chung SC. Upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 and p21 confers resistance to apoptosis in human gastric cancer cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:503–513. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lavrovsky Y, Schwartzman ML, Levere RD, Kappas A, Abraham NG. Identification of binding sites for transcription factors NF-kappa B and AP-2 in the promoter region of the human heme oxygenase 1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5987–5991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mimuro H, Suzuki T, Tanaka J, Asahi M, Haas R, Sasakawa C. Grb2 is a key mediator of Helicobacter pylori CagA protein activities. Mol Cell. 2002;10:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00681-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Churin Y, Al-Ghoul L, Kepp O, Meyer TF, Birchmeier W, Naumann M. Helicobacter pylori CagA protein targets the c-Met receptor and enhances the motogenic response. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:249–255. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bauer B, Bartfeld S, Meyer TF. H. pylori selectively blocks EGFR endocytosis via the non-receptor kinase c-Abl and CagA. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:156–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keates S, Keates AC, Katchar K, Peek RM, Jr, Kelly CP. Helicobacter pylori induces up-regulation of the epidermal growth factor receptor in AGS gastric epithelial cells. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:95–103. doi: 10.1086/518440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keates S, Keates AC, Warny M, Peek RM, Jr, Murray PG, Kelly CP. Differential activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in AGS gastric epithelial cells by cag+ and cag- Helicobacter pylori. J Immunol. 1999;163:5552–5559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Snider JL, Allison C, Bellaire BH, Ferrero RL, Cardelli JA. The beta1 integrin activates JNK independent of CagA, and JNK activation is required for Helicobacter pylori CagA+-induced motility of gastric cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13952–13963. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800289200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allison CC, Kufer TA, Kremmer E, Kaparakis M, Ferrero RL. Helicobacter pylori induces MAPK phosphorylation and AP-1 activation via a NOD1-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2009;183:8099–8109. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakayama M, Hisatsune J, Yamasaki E, Isomoto H, Kurazono H, Hatakeyama M, Azuma T, Yamaoka Y, Yahiro K, Moss J, et al. Helicobacter pylori VacA-induced inhibition of GSK3 through the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1612–1619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806981200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chou YH, Ho FM, Liu DZ, Lin SY, Tsai LH, Chen CH, Ho YS, Hung LF, Liang YC. The possible role of heat shock factor-1 in the negative regulation of heme oxygenase-1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:604–615. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh IS, Viscardi RM, Kalvakolanu I, Calderwood S, Hasday JD. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha transcription in macrophages exposed to febrile range temperature. A possible role for heat shock factor-1 as a negative transcriptional regulator. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9841–9848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Song M, Pinsky MR, Kellum JA. Heat shock factor 1 inhibits nuclear factor-kappaB nuclear binding activity during endotoxin tolerance and heat shock. J Crit Care. 2008;23:406–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang WP, Guo X, Koo MW, Wong BC, Lam SK, Ye YN, Cho CH. Protective role of heme oxygenase-1 on trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G586–G594. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.2.G586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Otterbein LE, Bach FH, Alam J, Soares M, Tao Lu H, Wysk M, Davis RJ, Flavell RA, Choi AM. Carbon monoxide has anti-inflammatory effects involving the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Nat Med. 2000;6:422–428. doi: 10.1038/74680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kapturczak MH, Wasserfall C, Brusko T, Campbell-Thompson M, Ellis TM, Atkinson MA, Agarwal A. Heme oxygenase-1 modulates early inflammatory responses: evidence from the heme oxygenase-1-deficient mouse. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1045–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63365-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pae HO, Oh GS, Choi BM, Chae SC, Kim YM, Chung KR, Chung HT. Carbon monoxide produced by heme oxygenase-1 suppresses T cell proliferation via inhibition of IL-2 production. J Immunol. 2004;172:4744–4751. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tzima S, Victoratos P, Kranidioti K, Alexiou M, Kollias G. Myeloid heme oxygenase-1 regulates innate immunity and autoimmunity by modulating IFN-beta production. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1167–1179. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Choi BM, Pae HO, Jeong YR, Kim YM, Chung HT. Critical role of heme oxygenase-1 in Foxp3-mediated immune suppression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;327:1066–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.