Abstract

In response to infection CD8+ T cells integrate multiple signals and undergo an exponential increase in cell numbers. Simultaneously, a dynamic differentiation process occurs, resulting in the formation of short-lived (SLEC; CD127lowKLRG1high) and memory-precursor (MPEC; CD127highKLRG1low) effector cells from an early-effector cell (EEC) that is CD127lowKLRG1low in phenotype. CD8+ T cell differentiation during vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) infection differed significantly than during Listeria monocytogenes infection with a substantial reduction in EEC differentiation into SLECs. SLEC generationwas dependent on Ebi3 expression. Furthermore, SLEC differentiation during VSV infection wasenhanced by administration ofCpG-DNA, through an IL-12 dependent mechanism. Moreover, CpG-DNAtreatment enhanced effector CD8+ T cell functionality and memory subset distribution, but in an IL-12 independent manner. Population dynamics were dramatically different during secondary CD8+ T cell responses, with a much greater accumulation of SLECs and the appearance of a significant number of CD127highKLRG1highmemory cells, both of which were intrinsic to the memory CD8+ T cell. These subsets persisted for several months, but were less effective in recall than MPECs. Thus, our data shed light on how varying the context of T cell priming alters downstream effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation.

Introduction

Pathogen-specific CD8+ T cells are activated after interaction with their cognate antigen presented by antigen-presenting cells, such as dendritic cells, in secondary lymphoid organs. This activation results in the clonal expansion and differentiation of the minute naïve antigen-specific CD8+ T cell population into a larger pool of effector cytotoxic T lymphocytes necessary for the clearance of intracellular pathogens. During this processthe antigen-presenting cells canactively shape the CD8+ T cell response by their expression of co-stimulators and secretion of cytokines.By the peak of the CD8+ T cell response both memory-precursors and terminally differentiated CTLs can be identified. Originally, these two subsets were solely identified based on CD127 (IL-7Rα expression levels (1,2), but more recent studies haveused CD127 expression in concert with killer cell lectin-like receptor G1 (KLRG1)2 expression (3,4). In these studies, memory-precursor effector cells (MPEC) were shown to be CD127high KLRG1low, while short-lived effector cells (SLEC) were CD127low KLRG1high in phenotype (3,4).

Interestingly, a single naïve antigen-specific CD8+ T cell can give rise to all the different effector and memory cell lineages observed after infection (5,6). Only recently have the factors regulating the differentiation of these subsets begun to be identified. Early work demonstrated that neither TCR- nor cytokine-mediated signals alone were sufficient for expression of KLRG1 on CD8+ T cells (7). More recent studies have shown that early inflammatory mediators in conjunction with TCR engagement can regulate the differentiation of the SLEC population (8). Two inflammatory mediators shown to be important in the differentiation of the SLEC population are IL-12 (3,8)and IL-2 (9-14). These cytokines work by regulating the levels of transcription factors (i.e. T-bet, Eomes, Blimp1, Bcl6) important in regulating effector and memory CD8+ cell differentiation (3,11,15). However, the role of other cytokines, such as IL-27 and type I interferons(16), that regulate these transcription factors in SLEC/MPEC differentiation remains unknown. Furthermore, the balance between the SLEC and MPEC differentiation seems to teeter on the metabolic status of the cells, because modulation of both mTOR and AMPK activity alters the differentiation pathway of effector CD8+ T cells (17-19). The mTOR pathway is crucial for integrating signals from the TCR, co-stimulatory receptors, and cytokines (20). This integration of signals seems to play a dominant role in regulating the expression pattern of transcription factors important for effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation.

During the development of vaccines an additional layer of complexity exists because in most situations a prime-boost regimen has been proposed to enhance T cell potency (21-24). This regimen works by greatly enhancing the absolute number of pathogen-specific T cells. Only recently have we begun to explore the functional consequences of multiple encounters with the same antigen. In these studies, it was demonstrated that secondary memory CD8+ T cells had elevated levels of granzyme B and decreased levels of CD62L and CD27 (25,26). Furthermore, global genetic analysis revealed drastic differences in memory T cells after primary through quaternary antigenic stimulation (27). However, the effector/memory differentiation dynamics in these situations has remained understudied.More importantly, whether all pathogens and vaccine vectors induce similar effector CD8+ T cell differentiation remains an open question. Here we demonstrate that effector CD8+ T cell differentiation differs substantially after vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) and L. monocytogenes (LM) infections. These differences were tied to the composition of the inflammatory milieu induced by each infection. Inflammation not only altered SLEC/MPEC differentiation, but also had a striking effect on the functionality of the effector CD8+ T cell population and composition of the MPEC population by limiting the differentiation of CD62Llow TEM cells. Additionally, multiple encounters with antigen dramatically altered SLEC/MPEC differentiation in a memory cell intrinsic manner. Thus, our data shed light on the fact that effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation is dynamically controlled and varies depending on the context of the activation, i.e. the type of priming pathogen or the number of times the cell is simulated with the same antigen.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Female C57BL/6 and B6-Ly5.2 mice between 5-8 weeks old were purchased from the National Cancer Institute, while female B6.129S1-Il12atm1Jm/J (p35−/−) and B6.129S7-Ifngtm1Ts/J (IFNγ−/−) mice between 6-8 weeks old were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Female B6.129X1-Ebi3tm1Rsb/J (Ebi3−/−) mice were provided by Dr. David Pascual (Montana State University). Female B6.129P2.Il18tm1Aki/J (IL-18−/−) mice were provided by Dr. Mark Jutila (Montana State University). OT-I Rag−/− mice were bred in the University of Connecticut Health Center animal facility. OT-I mice deficient for IFNAR were provided by Dr. John Harty (University of Iowa), whereas OT-I mice deficient for IL12rβ or both IL12rβ and IFNAR were provided by Dr. Matthew Mescher (University of Minnesota). All animal protocols were approved by either the University of Connecticut Health Center or Montana State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Pathogens, infections, and treatments

Both the recombinant VSV expressing ovalbumin (28) and recombinant LM expressing ovalbumin (29) have been previously described. For primary infections, mice were infected i.v. with either 105 plaque-forming units (PFU) of VSV-ova (Indiana) or 103 colony-forming units (CFU) of LM-ova. To study the recall response, mice were challenged with 2×106 PFU of VSV-ova (New Jersey) or 5×104 CFU of LM-ova. Some VSV infected mice were treated i.p. with 50μg of ODN1826 (Invivogen) given 1 hour after infection. Furthermore, some VSV infected mice were treated i.p. with two doses of 0.5μg of recombinant murine IL-12 (Peprotech) given 1 and 24 hours post-infection.

Systemic cytokine/chemokine analysis

Three groups of mice were analyzed: 1) LM infected, 2) VSV infected, and 3) VSV infected and treated with 50μg ODN1826. Peripheral blood was collected at 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours. Serum was collected 3 hours later by centrifugation. Serum was then frozen at −80°C until used. Three different Luminex™-based multiplex bead assay plates were used to quantify: 1) IFNα and IFNβ (Affymetrix); 2) G-CSF, GM-CSF, IFNγ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12p40, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-17, IL-23, IP-10, RANTES, and TNFα (Affymetrix); 3) IL-16, IL-21, IL-22, IL-25, IL-28B, MCP-5, MIP-3α, and MIP-3β (Millipore).

Tissue sample preparation and flow cytometric analysis

The H-2Kb tetramer containing the ovalbumin derived peptide SIINFEKL was generated as previously described (30,31). Analysis of endogenous antigen-specific CD8+ T cells throughout the entire immune response was conducted as has previously been described (32).

Intracellular cytokine staining

Cells were incubated with 1 μg/ml of the Ova or VSV-N peptideplus 1 μl GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences) in medium at 37°C for 4.5 h. Cells were stained for cell surface antigens on ice for 15 minutes. Cells were then fixed and rendered permeable using BD Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences) before stainingwith antibodies to IFNγ and TNFα.

Secondary memory adoptive transfer

To generate secondary memory mice C57BL/6 mice were initially infected with 103 CFU of LM-ova then >200 days later mice were rechallenged with 5×104 CFU of LM-ova. Approximately 30 days after secondary infection mice were sacrificed and their spleens collected. CD8+ T cells were enriched using magnetic beads and the CD8+ enrichment kit and AutoMACS (Miltenyi Biotech). Cells were then stained with anti-CD11a, anti-CD44, anti-KLRG1, anti-CD127, anti-classII, and anti-CD4. Memory phenotype cells (ClassIIneg CD4neg CD11ahigh CD44high) were sorted into three populations: 1) CD127high KLRG1low (MPEC), 2) CD127high KLRG1high (DPEC), and 3) CD127low KLRG1high (SLEC). Cells were sorted using a FACS Aria (BD Bioscience). After sorting, an aliquot of cells was further stained with anti-CD8α and Ova/Kb in order to enumerate the number of Ova/Kb-specific CD8+ T cells in each memory population. For adoptive transfer 104 Ova/Kb-specific CD8+ T cells were transferred to naïve CD45.1+ C57BL/6 mice. One day later mice were infected with 104 CFU of LM-ova.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined by either a paired Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA using Prism 5 (Graphpad Software). Significance was set as any p-value less than 0.05 (p<0.05).

Results

Effector CD8+ T cell subset generation differs between L. monocytogenes and VSV infection

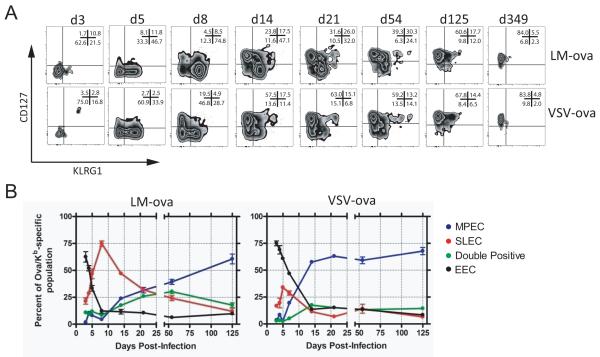

During the CD8+ T cell response, a large number of cytotoxic effector cells are generated. Recent studies have identified subsets of effector cells generated after lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection based on CD127 and KLRG1expression(3,4). At the peak of the response to LCMV infection the predominant CD8+ T cell population is CD127low KLRG1high, representing SLECs, while a small population of CD127high KLRG1low MPECs is also found. To examine whether the effector cell subsets present following VSV and LM infections were similar to those found after LCMV infection, mice were infected intravenously with 105 PFU of a recombinant VSV expressing ovalbumin (VSV-ova) or 103 CFU of a recombinant LM expressing ovalbumin (LM-ova). Subsequently, Ova/Kb-specific CD8+ T cells were monitored longitudinally using a recently described tetramer enrichment protocol(32,33) to examine the phenotype of early responding populations. On day 3 post-infection with either VSV or LM, the early effector CD8+ T cells (EEC) were primarily CD127low KLRG1low. Two days later, the SLEC and MPEC populations began to emerge after either infection (Figure 1A). Notably, approximately twice as many EEC remained after VSV infection as compared to LM infection.By day 8 the effect was even more dramatic, with ~75% of tetramer+ cells being SLECs, while only a small population of MPEC (~5%)emerged after LM infection. Comparatively, 8 days after VSV infection, 40-50% of tetramer+ cells remained as EEC with ~30% and ~20% of the cells being SLECs and MPECs, respectively. Over time, CD127highKLRG1low memory CD8+ T cells gradually became the dominant population after either infection, but this occurred much more rapidly following VSV infection (Figure 1A&B). Fifteen days after VSV infection, approximately 50% of the population was MPEC, while this occurred only at ~100 days after LM infection. A notable population of “double positive” effector cells (DPEC), i.e. CD127high KLRG1high cells, was also observed after LM infection, which was less evident during VSV infection (Figure 1A&B). In fact, ~50 days after LM-ova infection, the antigen-specificpool was distributed roughly equally between MPEC, SLEC and DPEC subsets. Quantification of the effector populations at the peak of the CD8+ T cell response revealed that the number of MPEC/EEC, rather than the overall number of Ova/Kb-specific CD8+ T cells more closely correlated to the size of the memory population (Figure S1). Thus, effector CD8+ T cell populations generated by VSV and LM infection substantially differed in kinetics and composition.

Figure 1. Effector cell subset differentiation differs following VSV and LM infection.

Mice were infected i.v. with either VSV-ova or LM-ova. At the indicated times the Ova/Kb-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleen were monitored for expression of KLRG1 and CD127. (A) Representative plots show the expression of KLRG1 and CD127 on the Ova/Kb-specific CD8+ T cells. Plots are representative of 4-5 mice per time-point and three independent experiments. In the upper right corner of each plot is the mean percentage of the population in each quadrant. (B) Graphical depiction of the Ova/Kb-specific effector CD8+ T cell sub-population dynamics following LM (left graph) or VSV (right graph) infection. Each dot represents the mean of 4-5 individual mice ± one SEM. Each color represents an effector cell sub-population: CD127low KLRG1low, early effector cells (black); CD127low KLRG1high, short-lived effector cells (red); CD127high KLRG1low, memory-precursor effector cells (blue); CD127high KLRG1high (green). These data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Developmental potential of effector CD8+ T cell subsets

Although the population kinetics just described suggested that EEC may be progenitors to the other effector subsets, we wished to test the developmental potential of each of the populations. To do so, a small number of OT-I cells was transferred and the mice were infected with VSV-ova (Figure 2). Five days later EEC, SLEC, and MPEC were purified by sorting and transferred to infection-matched mice. Two days after transfer,the purified SLECs largely remained as SLEC and did not produce any MPECs. In contrast,the sortedEEC population not only generated both MPECs and SLECs,but also additional EECs. Purified MPECs developed into MPECs, as well as EECs. Thirty five days after transfer, SLEC-derived cells were undetectable; in contrast,sorted EECs primarily developed into CD127high KLRG1low memory CD8+ T cells, while transferred MPECs focused exclusively to CD127high KLRG1lowmemory CD8+ T cells. Thus, EECs have the greatest developmental potential with the ability to generate all effector CD8+ T cell lineages.

Figure 2. Early effector CD8+ T cells have the greatest development potential.

Five days after VSV-ova infection CD11ahigh CD45.1+ OT-I CD8+ T cells were sorted into three populations: SLEC (CD127low KLRG1high), EEC (CD127low KLRG1low), and MPEC (CD127high KLRG1high). After which, 104 CD45.1+ OT-I CD8+ T cells were transferred into infection matched CD45.2+ mouse. Either 2 or 35 days later expression of KLRG1 and CD127 was assessed on the transferred CD45.1+ OT-I CD8+ T cells in the spleen. These data are representative of 2 independent experiments, each containing 3-4 mice per group.

Universal granzyme B expression by effector CD8+ T cell subsets, but hierarchal loss of expression

Although the EEC population appears to be highly activated, we wanted to confirm whether all such cells had lytic potential. To do this, mice were infected with VSV-ova or LM-ova and subsequently granzyme B levels in the responding CD8+ T cell subsets were assessed by flow cytometry. Five days after infection each of the antigen-specific CD8+ T cell subpopulations contained high levels of granzyme B (Figure S2).Interestingly, only two days later (day 7 post-infection) certain effector CD8+ T cell subpopulations began to lose granzyme B expression in a hierarchical manner: first CD62Lhigh MPEC followed by CD62Llow MPEC and then the EEC population followed by the SLEC subset (Figure S2). Furthermore, there were notable differences in granzyme B expression depending on the infection. In general, VSV-specific effectors expressed less granzyme B as compared to LM-specific effectors, and the VSV-specific MPEC populations rapidly lost granzyme B expression.Thus, there appeared to be a hierarchical programming of at least granzyme B expression in the effector subpopulations.

IL-12 and IFNα/β differentially regulateSLEC differentiation after L. monocytogenes and VSV infection

Optimal activation of the CD8+ T cell response has been shown to be controlled by three distinct signals during priming: 1) pMHC:TCR engagement, 2) co-stimulation, and 3) cytokines (34). Recent work demonstrates that SLEC differentiation following LCMV and L. monocytogenes infection is controlled at the time of priming by the inflammatory milieu (3,9,35). Two of the cytokines shown to beintimately involved in activation, differentiation, expansion, and survival of CD8+ T cells are IL-12 and IFNα/β(3,36-41).To study the effects of IL-12 and IFNα/β signaling on the differentiation of SLEC and MPEC populations, equal numbersof WTand either IL12rβ−/−, IFNAR−/−, IL12rβ−/−/IFNAR−/− OT-I cellswere co-transferred into WT C57BL/6 mice (Figure 3A). Effector CD8+ T cell differentiation following either VSV-ova or LM-ova infection were measured in the peripheral blood. Following VSV-ova infection there was no difference observed between WT and IL12rβ−/− OT-I cells in their ability to generate the effector subsets (Figure 3B), but a ~2-fold reduction in expansion was noted (data not shown). In contrast, following LM-ova infection IL-12rβ−/− OT-I cells did not undergo differentiation to the SLEC population as efficiently as WT OT-I cells did, which resulted in a relative increasein EEC and MPEC (Figure 3B) and a ~5-fold reduction in expansion was observed (data not shown). Moreover, following either LM-ova or VSV-ova infection IFNAR−/−and IL12rβ−/−/ IFNAR−/−OT-I cells failed to generate the SLEC population as well as WT OT-I cells (Figure3C & 3D). In all cases, EEC and MPEC subsets were increased suggesting that inflammatory signals acting at the EEC stage were driving SLEC development and that MPEC generation was the ‘default’ pathway. Furthermore, IFNAR−/− and IL12rβ−/− / IFNAR−/− OT-I cells failed undergo as robust expansion after both VSV and LM infection when compared to WT OT-I cells; during VSV infection effector CD8+ T cell expansion was ~9-fold and ~100-fold reduced, respectively, while during LM infection effector CD8+ T cell expansion was ~6-fold and ~400-fold reduced, respectively (data not shown). Thus, our results indicated that both IL-12 and IFNα/βwere important factors driving SLEC differentiation following LM infection, while only IFNα/βwas important following VSV infection. However, in either case some SLEC differentiation was apparent indicating that additional factors were involved in the SLEC differentiation pathway, such as perhaps IL-2 (9,10).

Figure 3. Differential role of IFNAR and IL-12rβin effector CD8+ T cell differentiation following VSV and LM infection.

(A) Wild-type (CD45.1/2+) OT-I CD8+ T cells and cytokine receptor deficient (CD45.2+) OT-I CD8+ T cells were co-transferred to CD45.1+ mice. Mice were infected 18 hours later i.v. with either VSV-ova or LM-ova. Seven days later the Ova/Kb-specific CD8+ T cells in the PBL were monitored for differentiation of effector CD8+ T cell subsets based on KLRG1 and CD127 expression. Three sets of mixed OT-I adoptive transfers were analyzed: WT:IL-12rβ−/−(B), WT:IFNAR−/− (C), and WT:IL-12rβ−/− IFNAR−/− (D).Each bar represents the median ± one SEM. Each graph represents the mean of 4-5 mice per group and at least 2 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using a paired Student’s t-test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01)

Overt inflammation mediated through IL-12 enhances SLEC differentiation during VSV infection

Our previous result indicated that the inflammatory milieu induced by LM and VSV infection differed significantly.Specifically, IL-12 mediated signals appearedto be lacking during VSV infection because IL-12rβ-deficiency had minimal effect on CD8+ T cell differentiation (Figure 3B). To examine the early systemic inflammatory milieu induced during VSV and LM infection serum was collected 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours post-infection and analyzed using a multiplex cytokine/chemokine panel (Figure S3). VSV infection induced high levels of IFNα, while LM infection did not. In contrast, LM infection induced a low level of IFNβwhich was not evident after VSV infection. LM infection was a potent inducer of Th1 pro-inflammatory cytokines, as evidenced by IL-6, IL-12p70, and IFNγ production, whereas VSV infection failed to elicit these cytokines, at least to levels that were detectable in the blood.Additionally, both IL-9 and IL-22 were increased following LM infection, but were not after VSV infection. Following both LM and VSV infection the expression of IP-10 (CXCL10), G-CSF, and IL-16 was observed.

Considering the major differences in the cytokine milieu generated in response to the different infections, it wasof interest to test whether altering the inflammatory conditionsresulted in alterations in effector cell subset development. To this end, we treated VSV infected mice with 50μg of ODN1826, a type B CpG-containing oligonucleotide which resulted in induction of IL-12p70, IL-9, and IL-22, as well as enhanced expression of IP-10 and G-CSF (Figure S3, blue lines).Treatment of mice with ODN1826 at the time of VSV infection did not alter effector CD8+ T cell expansion (Figure 4A). However, ODN1826 treatment didresult in significantly greater SLEC differentiation as compared to control mice (Figure 4B&C), which the result of a loss of approximately half the EEC and MPEC subsets. Treatment ofmice with a control oligonucleotide lacking the CpG motif or ODN1584, a type A CpG-containing oligonucleotide that does not induce IL-12p70 expression, did not alter the effector CD8+ T cell differentiation pathway (data not shown). Since IL-12 has been shown to be important in the induction of T-bet and subsequent SLEC differentiation(3), we next tested whether IL-12 was necessary for the ODN1826-induced SLEC differentiation, as well as whether IL-12 was sufficient to promote SLEC formation. To test this hypothesis C57BL/6 and p35−/− mice were either left untreated, treated with 50μg of ODN1826, or treated with recombinant murine IL-12 at the time of VSV-ova infection. Infection of C57BL/6 and p35−/− mice resulted in similar effector CD8+ T cell expansion and differentiation (Figure 4A-C). Treatment of C57BL/6 mice with ODN1826 significantly enhanced SLEC differentiation (Figure 4B&C). However, ODN1826 treatment of p35−/− mice did not result in augmentation of SLEC differentiation (Figure 4B&C), indicating that IL-12 was necessary for the enhanced SLEC differentiation following ODN1826 administration. Treatment of C57BL/6 mice with recombinantmurine IL-12 at the time of VSV infection resulted in an enhancement of SLEC differentiation (Figure 4B&C), demonstratingthat IL-12 was sufficient for enhancing SLEC differentiation after VSV infection.Thus, the limited SLEC differentiation observed during VSV infection appears to be due to a lack of IL-12 mediated events which can be mimicked with IL-12-inducing adjuvants.

Figure 4. ODN1826 enhances SLEC differentiation through an IL-12 and Ebi3 dependent mechanism.

(A-C) C57BL/6 and p35−/− mice were infected i.v. with VSV-ova. After viral infection, some mice were treated with either 50μg ODN1826 (within 2 hours) or 0.5μg rIL-12 (two doses, 1 hour and 24 hours). Seven days later the VSV-N/Kb-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleen were identified by tetramer staining. Absolute number of VSV-N/Kb-specific CD8+ T cells (A), while effector CD8+ T cell differentiation was then assessed based on KLRG1 and CD127 expression by flow cytometry (B) and each effector sub-population was quantified as a percentage of the tetramer+ CD8+ T cell population (C). (D-E) C57BL/6 and Ebi3−/− mice were infected i.v. with VSV-ova. After viral infection, some mice were treated with either 50μg ODN1826 (within 2 hours). Seven days later the Ova/Kb-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleen were identified by tetramer staining. Absolute number of Ova/Kb-specific CD8+ T cells (D) while effector CD8+ T cell differentiation was then assessed based on KLRG1 and CD127 expression by flow cytometry (E) and each effector sub-population was quantified as a percentage of the tetramer+ CD8+ T cell population (F). For panels B &E representative contour plots show the expression of KLRG1 and CD127 on the antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. In the upper right corner of each plot is the mean percentage of the population in each quadrant, which is graphed in panels C & F. Statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA (*p<0.05 and **p<0.01). These data are representative of 4-5 mice per group and two independent experiments.

IL-27/Ebi3 contributes to SLEC differentiation during VSV infection

Previous studies have shown that SLEC differentiation is highly dependent on T-bet (3). Infection of Tbx21−/− mice with VSV resulted in severely impaired SLEC differentiation (data not shown), but SLEC differentiation during VSV infection occurs independently of IL-12 (Figure 4B&C), which is the prototypic inducer of T-bet expression (42). Thus, it was of interest to test whether other cytokines that induced T-bet expression could regulate effector cell subset development. Other cytokines known to regulate T-bet expression include IL-18 (43), IL-27 (44), and IFNγ(45,46). To this end, we infected C57BL/6, IL-18−/−, IFNγ−/−and Ebi3−/− mice with VSV-ova. IL-18 had minimal effect on the differentiation of effector CD8+ T cells during VSV infection with or without ODN1826 treatment (Figure S4A). Also, IFNγ deficiency had only a slight impact on SLEC differentiation after ODN1826 treatment (Figure S4B). More interestingly, while effector CD8+ T cell expansion was largely independent of Ebi3 (Figure 4D), differentiation of SLECs was markedly impaired in Ebi3−/− mice, with nearly a 2-fold reduction in SLEC differentiation (Figure 4E&F). Simultaneously, there was an increase in the proportion of MPECs found, while EECs remained largely unchanged (Figure 4E&F). Next, we examined whether Ebi3 expression was necessary for the ODN1826-mediated enhancement of SLEC differentiation after VSV infection. To this end, C57BL/6 and Ebi3−/− mice were infected with VSV-ova and one day later treated with 50μg of ODN1826. Like our previous results, treatment of C57BL/6 mice with ODN1826 significantly enhanced SLEC differentiation (1.73-fold increase), while decreasing the proportion of EECs and MPECs (Figure 4E&F). Similarly, ODN1826 treatment enhancedSLEC differentiationwas still observed in Ebi3−/− miceas compared to controls (1.79-fold increase), but the overall proportion of SLECs will still significantly decreased compared to ODN1826 treated C57BL/6 mice(Figure 4E&F). Thus, Ebi3, and therefore likely IL-27, playeda prominent role in the generation of SLECs and furthermore appeared to actindependently of IL-12.

ODN1826 treatment enhances effector CD8+ T cell cytokine production during VSV infection

Generating polyfunctional effector and memory CD8+ T cells provides optimal protective capabilities (47).Previous results show that after LM infection the effector CD8+ T cell population is largely polyfunctional, producing both IFNγ and TNFα and producing high levels of IFNγ on a per cell basis (48).In contrast, after VSV infection the effector CD8+T cell population appeared to be of lower quality (data not shown). Therefore, we tested whether enhancing the inflammatory milieu during VSV infection by treatment with ODN1826 would enhance the functionality of the responding CD8+ T cells. To test this we treated C57BL/6 or p35−/− mice with PBS, 50μg ODN1826, or 1μg rIL-12. Seven days later we analyzed cytokine production from the effector CD8+ T cells found in the spleen by intracellular cytokine staining after a 4.5h re-stimulation with peptide. VSV infection of C57BL/6 or p35−/− mice induced a substantial population of IFNγproducers but only ~25% of these produced TNFα (Figure 5). When C57BL/6 mice were treated with either ODN1826 or rIL-12 the quality of the effector CD8+ T cells improved as judged by production of higher levels of IFNγ on a per cell basis (Figure 5A) and ~60% of the IFNγ+ cells producing TNFα (Figure 5B). Surprisingly, the functionality of the effector CD8+ T cells was similarly enhanced in ODN1826-treated p35−/− mice. Thus, while IL-12 was partially sufficient for increasing the functionality of the effector CD8+ T cells induced by VSV infection, IL-12 was not necessary for the enhancement of effector CD8+ T cells function following ODN1826.

Figure 5. ODN1826 enhances effector CD8+ T cell cytokine functionality through an IL-12 independent mechanism.

C57BL/6 and p35−/− mice were infected i.v. with VSV-ova. After viral infection, some mice were treated with either 50μg ODN1826 (within 2 hours) or 0.5μg rIL-12 (two doses, 1 hour and 24 hours). Seven days after infection the potential of CD8+ T cells to produce IFNγ and TNFα was assessed by intracellular cytokine staining. Either IFNγ mean fluorescent intensity (A) or the percentage of IFNγ+ TNFα+ cells (B) was examined. For each panel a representative FACS plot showing the typical cytokine profile and gating is shown. Graphs show the median for 4-5 mice per group and are representative of at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA and a Newman-Keuls post-test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001)

ODN1826 treatment limits formation of CD62Lloweffector-memory precursors during VSV infection

Memory CD8+ T cells are a heterogeneous population. Based on CD62L and CCR7 expression at least two populations of memory cells have been described (49,50). These populations are centralmemory cells that express both CD62L and CCR7, while effector memory cells lack expression of these proteins(50). Our previous results show that following VSV infection many more effector-memory CD8+ T cell precursors are generated as compared to LM infection(51). Here we examined whether treatment of VSV infected mice with ODN1826 altered the distribution of TCM and TEM precursors, as well as if IL-12 was necessary and sufficient for such alterations. To test this we treated C57BL/6 or p35−/− mice with PBS, 50μg ODN1826, or 1μg rIL-12.Seven days later we analyzed the proportion of antigen-specific CD62LhighMPECswithin the lymph nodes (Figure 6A & B), but similar effects were also observed in the spleen (data not shown). The percentage of CD62Lhigh MPECs was significantly enhanced after CpG treatment and this effect was partially IL-12 independent (Figure 6B). IL-12 injection did not enhance CD62LhighMPEC development. However, the absolute number of CD62LhighMPECs was not significantly changed irrespective of the treatment (Figure 6C), while the absolute number of CD62Llow MPECs after VSV infection was markedly lower in C57BL/6 mice treated with ODN1826, but not rIL-12 (Figure 6D).The effect of CpG treatment was again largely IL-12 independent. The differences in total numbers of cells compared to percentages can be explained by our findings showing that CpG treatment reduced the overall MPEC population (Figure 4). Nevertheless, within the MPEC compartment, CpG treatment enhanced CD62L expression in an IL-12 independent manner, similar to the enhancement of cytokine production by CpGtreatment (Figure 5).

Figure 6. ODN1826 limits CD62Llow MPEC differentiation in an IL-12 independent mechanism.

C57BL/6 and p35−/− mice were infected i.v. with VSV-ova. After viral infection, some mice were treated with either 50μg ODN1826 (within 2 hours) or 0.5μg rIL-12 (two doses, 1 hour and 24 hours). Seven days later the Ova/Kb-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleen were identified by tetramer staining. Memoryprecursor CD8+ T cells were identified based on KLRG1 and CD127 expression. The proportion of CD62LhighMPECs was assessed (A&B). Additionally, the absolute number of CD62Lhigh MPEC (C) and CD62Llow MPEC (D) were calculated. Each dot represents an individual mouse from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA and a Newman-Keuls post-test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001)

Effector cell population dynamics differ between primary and secondary CD8+ T cell responses

One strategy that has commonly been used to improve vaccine efficacy is a prime-boost regimen, in which the same antigen is given repeatedly over time typically in different vaccine vectors(21-24). Only recently have the functional outcomes of this prime-boost protocol been explored; repeated encounters with antigen resulted in memory populations that were more cytotoxic and less able to proliferate to subsequent antigen encounter (25-27). The reason(s) for these differences have not been determined. To address how repeated encounters with the same antigen impact effector and memory differentiation, we compared the CD8+ T cell response in mice infected with 103 CFU of LM-ova (1° LM) or 105 PFU of VSV-ova (1° VSV) to that of memory mice (>90 days after initial infection) challenged with 5×104 CFU of LM-ova (2° LM-LM or 2° VSV-LM) or 2×106 PFU VSV-ova (2° LM-VSV or 2° VSV-VSV). After infection, mice were serially bled and the Ova/Kb-specific CD8+ T cell response was analyzed. Surprisingly, the composition of the secondary responding populations was drastically different than what was observed during the primary response. This was especially evident during secondary VSV infection (Figure 7A). In all cases, the KLRG1high population predominated for substantially longer in the secondary response(Figure 7A). This resulted in a much more protracted appearance of MPEC in the secondary response. As compared to the primary response, the recall response was comprised of a much greater population of CD127high KLRG1high (DPEC) cells. Even at ~150 days aftersecondary infection, ~60-70% of the memory cells expressed KLRG1 and ~40% of those cells co-expressed CD127(data not shown). Thus, in the secondary response CD127 expression and the absence of KLRG1 did not correlate with survival.

Figure 7. CD8+ T cell-intrinsic enhancement of KLRG1 expression during secondary infection.

To compare the primary and secondary immune responses, naïve and memory C57BL/6 mice were infected with either VSV-ova or LM-ova. At either the peak of the CD8+ T cell response (d5 secondary infection or d7 primary infection) or 2 months post-infection, mice were bled and the Ova/Kb-specific CD8+ T cells were identified by tetramer staining and their expression of KLRG1 and CD127 was assessed (A). To determine if the enhanced KLRG1 expression was intrinsic to the memory CD8+ T cell, we co-transferred VSV-induced memory OT-I CD8+ T cells (CD45.1/2+) with naïve OT-I CD8+ T cells (CD45.2+). One day later those mice were infected with 106 PFU of VSV-ova and both the 1° and 2° effector CD8+ T cell populations were examined for expression of KLRG1, CD127, and CD62L (B).These data are representative of 2 independent experiments, each containing 4-5 mice per group.

We next tested whether the enhanced SLEC differentiation observed in the secondary response was cell intrinsic or the result of possible changes in the inflammatory milieu during the secondary infection. For these experiments we utilized the VSV model, as the difference between the primary and secondary responses was mostdramatic (Figure 7A). Experimentally, 104 memory OT-I cells (CD45.1/2+) were co-transferred with 104 naïve OT-I (CD45.1+) to naïve C57BL/6 mice that were infected one day later with VSV-ova. Analysis of both the naïve and memory OT-I cells revealed that a much greater proportion of the secondary CD8+ T cells expressed KLRG1 than did the cells responding for the first time (Figure 7B). In addition, many more primary cells expressed CD62L than did reactivated memory cells (Figure 7B). These data implied that memory CD8+ T cells had undergone genetic modifications that predisposed the cells to differentiate toward a SLEC phenotype upon secondary encounter with antigen, while the primary responders were largely influenced by environmental factors.

Recall and differentiation potential of the individual secondary memory CD8+ T cell subsets

Relatively little is known about the role of the effector/memory subsets in recall responses, especially with respect to the CD127high KLRG1high(DPEC) population. To test the capabilities of these three populations of secondary memory cells, memory phenotype CD8+ T cells (CD11ahigh CD44high) from CD45.2+ C57BL/6 mice previously infected and challenged with LM, were separated into CD127high KLRG1low, CD127high KLRG1high, and CD127low KLRG1high subsets. After sorting, 104Ova/Kb-specific CD8+ T cells of each population were transferred individually into naïve CD45.1+ C57BL/6 mice (Figure 8A). One day later mice were infected with 104 CFU of LM-ova and were subsequently bled at the indicated times to monitor expansion and effector cell differentiation. Each memory subsetgenerated a readily detectible effector CD8+ T cell population in the blood, indicating that each had undergone substantial expansion. CD127high KLRG1low memory cells mounted a robust tertiary expansion, while CD127low KLRG1high memory cells had a substantially diminished ability to undergo expansion (Figure 8B). Interestingly, CD127high KLRG1highmemory cells exhibited anintermediate abilityto undergo expansion upon re-encounter with antigen (Figure 8B).

Figure 8. Distinction recall potential and differentiation of secondary memory CD8+ T cell populations.

Secondary memory CD8+ T cells (CD45.2+) were sorted into SLEC (KLRG1high CD127low), DPEC (KLRG1high CD127high), and MPEC (KLRG1low CD127high) to >98% purity and 104 cells of each phenotype were adoptively transferred to naïve CD45.1+ mice. One day later those mice were challenged with 104 CFU of LM-ova (A). The recall kinetics (B) and subsequent tertiary effector CD8+ T cell differentiation (C) of the Ova/Kb-specific memory CD8+ T cell sub-populations was tracked in the PBL using CD45.2 expression to identify the adoptively transferred cells and KLRG1 and CD127 expression to monitor effector cell differentiation. In the upper right corner of each plot is the mean percentage of the population in each quadrant. These data are representative of 2 independent experiments, each containing 4-5 mice per group.

More intriguing was the subsequent effector cell differentiation from each purified memory subset. Recall of the CD127low KLRG1high population resulted in expansion of effector CD8+ T cells that exclusively retained the same phenotype (CD127low KLRG1high) even into memory (Figure 8C). When the CD127high KLRG1high memory population was recalled effector CD8+ T cells were largelyCD127low KLRG1high in phenotype; with time a CD127high KLRG1highmemory population emerged, but CD127high KLRG1lowcells never emerged (Figure 8C). Strikingly, only the CD127high KLRG1low memory population appeared to contain true ‘memory stem cells’ which were capable of re-generating all effector/memory cell subsets following re-challenge. The effector CD8+ T cell response generated by the sorted CD127high KLRG1low population was largely dominated by cells of CD127low KLRG1high phenotype, but small numbers of the other three effector CD8+ T cell populations could be found. With time CD127high KLRG1high and CD127high KLRG1lowphenotype cells increased in frequency (Figure 8C), similar to what was observed during the secondary immune response in intact mice (Figure 7A). Nonetheless, even by ~200 days after challenge only a small fraction of the cells were of the IL-7RhighKLRG1low phenotype (~10%). Thus, we have demonstrated the importance of generating large numbers of CD127low KLRG1high CD8+ T cells during prime-boost vaccination protocols in order to generate a memory pool which has ‘stem-cell’-like properties

Discussion

Immunological memory is the foundation of vaccination. Understanding the factors governing and regulating the differentiation of the memory pool are important for understanding vaccine efficacy or failure. Here we demonstrate that early after infection, naïve antigen-specific CD8+ T cells become activated and form an EEC pool that is CD127low KLRG1low in phenotype. These EECs then differentiate into MPECs (CD127high KLRG1low) or SLECs (CD127low KLRG1high). Further differentiation of the EECs was dependent on the context of the immune response. First, the inflammatory environment induced during thedifferent infections dramatically altered effector CD8+ T cell differentiation, effector cytokine production, and memory subset development. Second, multiple encounters with antigen altered effector CD8+ T cell population dynamics through a memory cell-intrinsic manner. Lastly, the make-up of the effector/memory population at the time of re-challenge dramatically impacted the dynamics of the subsequent immune response.

The origin of the memory CD8+ T cell population has long been debated. It is thought that memory cells must go through an effector cell stage (52-54). This concept is further supported by single cell adoptive transfer (5) and cellular bar-coding (6) experiments, which demonstrate that each naïve CD8+ T cell has the potential to generate all the effector and memory CD8+ T cell lineages described. Our data further support that memory CD8+ T cells pass through an obligatory effector state as all effector CD8+ T cell subsets expressed granzyme B on day 5 post-infection. However, with time effector CD8+ T cells lost granzyme B expression in a hierarchal manner (TCM MPEC → TEM MPEC → EEC → SLEC), which supports the progressive differentiation model of CD8+ T cell differentiation (55-57).The hierarchal loss of granzyme B expression is likely tied to the responsiveness of those populations to IL-2. IL-2 has been shown to stabilize granzyme B and perforin expression in effector CD8+ T cells (11); furthermore, we have shown that CD25/IL-2rα is expressed at higher levels on EECs and SLECs when compared to MPECs (9). Additionally, granzyme B levels were substantially lower after VSV infection when compared with LM infection. The lack of robust Th1 inflammation during VSV infection might explain why granzyme B levels were lower, because IL-6 and IL-12 enhance granzyme B expression in CD8+ T cells (11,58). Decreased expression of granzyme B could be one of the reasons why VSV is able to persist for up to 60 days in the host (59).

The decision to become either a SLEC or MPEC teeters on the transcription factor profile of the responding CD8+ T cells, with T-bet and Blimp-1 enhancing SLEC differentiation, while Eomesodermin(Eomes) and Bcl6 are important in MPEC differentiation (60-62). Recent work with Th1 CD4+ T cells demonstrated that T-bet repressed Tcf7 (TCF-1) expression (63); furthermore Tcf7 is an important transcription factor for memory CD8+ T cell development (64,65).Recent work has begun to identify the factors regulating these critical transcription factors. We have demonstrated that IL-2 signaling is important for SLEC differentiation (9); furthermore, IL-2 enhances Blimp-1 expression while repressing Bcl6 expression (11). IL-12 has been shown to induce the expression of Tbx21 (T-bet), while repressing Eomesin CD8+ T cells resulting in the accumulation of effector cells and limiting memory development (61). Other studies have shown that IL-12 is necessary for the accumulation of KLRG1high CD8+ T cells after Toxoplasma gondii infection (66) and vaccination with peptide pulsed dendritic cells (3,8), but not in other systems (67). Our data support the role of IL-12 in SLEC differentiation during strong Th1-like inflammation, i.e. LM infection or ODN1826 treatment. However, during VSV infection there was no role for IL-12 in mediating SLEC differentiation. This resulted in a large proportion of the effector CD8+ T cells retaining a CD127low KLRG1low phenotype, reminiscent of the EEC population. This was not unique to the VSV model, as intranasal infection with influenza A virus or infection with vaccinia virus by skin scarification resulted in a similar retention of early effector CD8+ T cells with the CD127low KLRG1low phenotype (data not shown). These data fit well with a previous report demonstrating that the CD8+ T cell response during LM infectionwas highly dependent on IL-12Rβ signal, while responses to viral infections were not (41).Nevertheless, after VSV infection ~40% of the effector CD8+ T cell population stillexpressed KLRG1.Here we showed that Ebi3, a component of IL-27 together with p28(68), regulated SLEC differentiation during VSV infection. IL-27 is an IL-12 cytokine family member, which is an important inducer of T-bet and IL-12rβ in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells via a STAT1-dependent mechanism (16,44). Interestingly, IFNαcan also induce T-bet and IL-12rβ expression in naïve T cells through a STAT1-dependent mechanism (16), which fits with our observation that IFNAR−/− CD8+ T cells had a reduced differentiation of SLECs. Our results might explain why after dendritic cell vaccination CpG DNA induced a more pronounced SLEC differentiation than IL-12 or IL-12/IFNγ treatment (3,8), because this reductionist system lacked IL-27 and/or type I interferons. In our system, we demonstrated that IFNγplayed only a minimal role, which contradicts previous work which suggests IFNγ enhances SLEC differentiation (8,69,70). This difference is likely due to the magnitude of IFNγ expression in those systems.In our hands use of ODN1826 as an adjuvant induced minimal IFNγ expression, whereas the other groups utilized live LM as an inflammatory adjuvant which induces robust levels of IFNγ.

Thus, our data together with published results support a modelin which high levels of inflammatory cytokines drive maximal SLEC differentiation while limiting MPEC generation. However, depending on the pathogen or vaccination protocol only a subset of these inflammatory cytokines may be expressed thus dampening SLEC differentiation and enhancing the number of MPECs generated (Figure 9A). Specifically,early IL-27 and IFNα expressionenhances T-bet and IL-12rβ expression in responding CD8+ T cells, beginning the SLEC differentiation process. Activated CD8+ T cells then respond to IL-12, if present. IL-12 signaling further augments T-bet expression in the responding CD8+ T cells enhancing SLEC differentiation. IL-12 signaling also amplifies CD25 expression on the responding CD8+ T cells (11), which promotes the expansion and differentiation of more SLECsthrough IL-2 signaling. Furthermore, IL-12 enhances IFNγproduction leading to a positive feedback loop of IFNγ on T-bet expression (71); thus, IFNγ can enhance SLEC differentiation (8) and/or expansion (72)in CD8+ T cells if IFNγ is highly expressed during the immune response. Subsequent survival of the SLEC population is highly sensitive to the balance of IL-15 and TGFβ, which promote their survival and death, respectively (73). A shift of this balance towards TGFβ might explain why CD8+ T cells induced by VSV infection equilibrate to a memory phenotype more quickly.

Figure 9. Model of SLEC/MPEC differentiation under different inflammatory conditions.

(A) The proportion of effector CD8+ T cells that differentiate into SLECs is highly dependent on the inflammatory milieu induced by infection or vaccination. Under conditions of high inflammation, such as after LM infection, SLEC differentiation is significantly enhanced by the expression of inflammatory cytokines, which include type I interferons (IFNα/β), Ebi3 (and therefore likely IL-27), IL-12 and IFNγ (top). In contrast, when only low levels of inflammation are induced, such as following DC vaccination (70), there is limited SLEC differentiation due to limited expression of inflammatory cytokines (bottom left). Mild inflammation results in fewer SLECs being generated, due to the limited expression of inflammatory cytokines. For example, during VSV infection type I interferons (IFNα/β) and Ebi3 are expressed, but IL-12 and IFNγare not expressed early. This inflammatory cytokine profile will result in significantly fewer SLECs being generated (middle). (B) ODN1826 treatment had significant effects on effector CD8+ T cell differentiation, which were either IL-12 –dependent or –independent. Enhancement of SLEC differentiation was highly dependent on IL-12, which is due to the ability of IL-12 to enhance T-bet expression (3). In contrast, enhancement of effector cytokine expression by ODN1826 treatment occurred through an IL-12-independent mechanism. Also, ODN1826 shifted the TCM/TEM ratio in favor of TCM generation through an IL-12-independent mechanism.

In addition to enhancing SLEC differentiation, CpG-induced inflammation limited TEM differentiation and enhanced CD8+ T cell poly-functionality. In contrast to the enhanced SLEC differentiation, both of these inflammation-induced alterationsto the CD8+ T cell population occurred through an IL-12 independent pathway (Figure 9B). Alterations in TCM/TEM differentiation could be the result of changes in the levels of IL-15 and IL-2, which we have previously shown to be important in TCM and TEM differentiation, respectively(51). CpG treatment has been shown to enhance IL-15 expression (74), which could maintain TCM MPEC numbers while the CD62Llow cells are driven towards terminal effectors. In addition to altering inflammatory cytokine production, CpG treatment alters expression of co-stimulatory molecules(75). Specifically,co-stimulation through OX40:OX40L interactions during vaccinia virus infectionresulted in CD8+ T cellswith greater functionality(76). Thus, it is likely that multiple cytokines and co-stimulatory pathways simultaneously play a crucial role in regulating effector CD8+ T cell differentiation.

Importantly, our studies demonstrated that multiple encounters with the same antigen had dramatically different outcomes on the CD8+ T cell response even when the same priming vector was utilized. This observation has important implicationsfor the development of effective prime-boost vaccination protocols. Because of the ease of genetic manipulation and ability to induce strong cellular immune responses, both L. monocytogenes and VSV have been postulated to be effective vaccine vectors for the induction of strong T cell responses (77). Our data demonstrated that during secondary and tertiary infection more SLEC phenotype cells are generated and that these KLRG1high cells survive for prolonged periods of time. This was most dramatic following VSV infection, in which during primary infection ~30% of the effector CD8+ T cells were of SLEC phenotype, while during secondary VSV infection ~80% of the effector CD8+ T cells were of SLEC phenotype. Indeed, it might be worth considering modifying the current nomenclature since in the secondary response a substantial number of long-lived memory cells express KLRG1 either with or without CD127 expression. Previous studies demonstrate that secondary and tertiary memory populations appear more terminally differentiated, as measured by high expression of KLRG1 and low expression of CD27 and CD62L (25-27,78). Furthermore, we demonstrated that this enhanced SLEC formation was intrinsic to the memory CD8+ T cell, as co-adoptive transfer of naïve and memory CD8+ T cells into the same recipient resulted in the same phenomenon. Supporting this is the observation that in human memory CD8+ T cells the KLRG1 promoter region is in an open configuration (79). An alternative explanation for our observation is that memory cells express a different panel of cytokine/chemokine receptors which enables them to sense different cues and could result in enhancement of this terminally differentiated phenotype. Using a transcriptome approach Wirth et al. have found that numerous cytokine and chemokine receptors are differentially regulated in naïve and memory CD8+ T cells, such as IL-12rβ2, IL-2rα, CXCR3, and CCR7 (27), which are known to play important roles in regulating SLEC/MPEC differentiation(3,9,10,80). Thus, naïve and memory CD8+ T cells may express different cytokine receptors which could alter their ability to sense the inflammatory environment; for example, memory CD8+ T cells are known to be more sensitive to IL-18 (81). Consequently, it is crucial that we understand the factors regulating effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation under a range of differentiation conditions.

The heterogeneous nature of the memory populations begs the question as to which of the subpopulations are involved in responding to secondary and tertiary challenges and at what level. Since multiple encounters with the same antigens result in KLRG1high cells with prolonged life spans we examined how both the KLRG1high CD127low and KLRG1high CD127high phenotype memory CD8+ T cells may contribute to subsequent immune responses. Interestingly, the KLRG1low CD127high, classical memory cells, had the greatest recall potential and had the ability to generate all the effector CD8+ T cell populations, including more memory-precursors. In contrast, both KLRG1high memory cell populations were unable to regenerate KLRG1low CD127high memory-precursors, but were able to contribute to the recall response to varying degrees. KLRG1high CD127highphenotype memory cells underwent robust expansion, only about 2-4 fold less than the KLRG1low CD127high memory population; in contrast, KLRG1high CD127low phenotype memory cells had relatively poor recall potential, about 20-fold less than the KLRG1low CD127high memory population. It has been reported that Bmi-1 is necessary for optimal CD8+ T cell expansion and TCR-mediated Bmi-1 expression is reduced in KLRG1high CD8+ T cells (82), which might explain why both KLRG1high memory CD8+ T cell populations underwent less expansion than CD127high KLRG1low memory CD8+ T cells. In addition, KLRG1 may actively suppress CD8+ T cell proliferation, because monoclonal antibody blockade of KLRG1:E-cadherin interactions led to enhanced phosphorylated Akt, which in turn resulted in increased cyclin D, increased cyclin E, and decreased p27 resulting in more proliferation (83). Why the CD127highKLRG1high population is more competent for expansion than the CD127lowKLRG1high population remains unknown. One possibility is that IL-7 mediated signaling might partially overcome the inhibitory signals mediated by KLRG1. These findings have important implications in the development of prime-boost vaccination regimens, where the timing and formulation of boosters may be a critical factor in the generation of long-term protective immunity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Matthew Mescher and John Harty for providing cytokine receptor knock-out OT-I cells, as well as Drs. Mark Jutila and David Pascual for providing IL-18 and Ebi3 knock-out mice, respectively.The authors thank Diane Gran for expert assistance in conducting cell sorting.The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Footnotes

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grants R01-AI41576 (L.L.), RO1-AI76457 (L.L.), F32-AI074277 (J.J.O.), P20-RR020185 (J.J.O.), T32-AI07080 (D.A.B) and F32-AI84328 (E.R.J.). Additionally, the Montana State University Agricultural Experiment Station and equipment grants from the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust supported this work. The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Abbreviations used in this article: KLRG1, killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily G, member 1; MPEC, memory-precursor effector cell; SLEC, short-lived effector cell; EEC, early effector cell; DPEC, double-positive effector cell; VSV, vesicular stomatitis virus, LM, Listeria monocytogenes; LCMV, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus; TEM, effector-memory T cell; TCM, central-memory T cell; CFU, colony-forming units

References

- 1.Schluns KS, Kieper WC, Jameson SC, Lefrançois L. Interleukin-7 mediates the homeostasis of naive and memory CD8 T cells in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 2000;1:426–432. doi: 10.1038/80868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaech SM, Tan JT, Wherry EJ, Konieczny BT, Surh CD, Ahmed R. Selective expression of the interleukin 7 receptor identifies effector CD8 T cells that give rise to long-lived memory cells. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:1191–1198. doi: 10.1038/ni1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joshi NS, Cui W, Chandele A, Lee HK, Urso DR, Hagman J, Gapin L, Kaech SM. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8(+) T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity. 2007;27:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarkar S, Kalia V, Haining WN, Konieczny BT, Subramaniam S, Ahmed R. Functional and genomic profiling of effector CD8 T cell subsets with distinct memory fates. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:625–640. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stemberger C, Huster KM, Koffler M, Anderl F, Schiemann M, Wagner H, Busch DH. A single naive CD8+ T cell precursor can develop into diverse effector and memory subsets. Immunity. 2007;27:985–997. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerlach C, van Heijst JW, Swart E, Sie D, Armstrong N, Kerkhoven RM, Zehn D, Bevan MJ, Schepers K, Schumacher TN. One naive T cell, multiple fates in CD8+ T cell differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:1235–1246. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robbins SH, Terrizzi SC, Sydora BC, Mikayama T, Brossay L. Differential regulation of killer cell lectin-like receptor G1 expression on T cells. J. Immunol. 2003;170:5876–5885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.5876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui W, Joshi NS, Jiang A, Kaech SM. Effects of Signal 3 during CD8 T cell priming: Bystander production of IL-12 enhances effector T cell expansion but promotes terminal differentiation. Vaccine. 2009;27:2177–2187. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obar JJ, Molloy MJ, Jellison ER, Stoklasek TA, Zhang W, Usherwood EJ, Lefrancois L. CD4+ T cell regulation of CD25 expression controls development of short-lived effector CD8+ T cells in primary and secondary responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:193–198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909945107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalia V, Sarkar S, Subramaniam S, Haining WN, Smith KA, Ahmed R. Prolonged interleukin-2Ralpha expression on virus-specific CD8+ T cells favors terminal-effector differentiation in vivo. Immunity. 2010;32:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pipkin ME, Sacks JA, Cruz-Guilloty F, Lichtenheld MG, Bevan MJ, Rao A. Interleukin-2 and inflammation induce distinct transcriptional programs that promote the differentiation of effector cytolytic T cells. Immunity. 2010;32:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell DM, Ravkov EV, Williams MA. Distinct roles for IL-2 and IL-15 in the differentiation and survival of CD8+ effector and memory T cells. J. Immunol. 2010;184:6719–6730. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiesel M, Joller N, Ehlert AK, Crouse J, Sporri R, Bachmann MF, Oxenius A. Th cells act via two synergistic pathways to promote antiviral CD8+ T cell responses. J. Immunol. 2010;185:5188–5197. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Overstreet MG, Chen YC, Cockburn IA, Tse SW, Zavala F. CD4+ T cells modulate expansion and survival but not functional properties of effector and memory CD8+ T cells induced by malaria sporozoites. PLoS. One. 2011;6:e15948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takemoto N, Intlekofer AM, Northrup JT, Wherry EJ, Reiner SL. Cutting Edge: IL-12 inversely regulates T-bet and eomesodermin expression during pathogen-induced CD8+ T cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 2006;177:7515–7519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hibbert L, Pflanz S, de Waal MR, Kastelein RA. IL-27 and IFN-alpha signal via Stat1 and Stat3 and induce T-Bet and IL-12Rbeta2 in naive T cells. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2003;23:513–522. doi: 10.1089/10799900360708632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearce EL, Walsh MC, Cejas PJ, Harms GM, Shen H, Wang LS, Jones RG, Choi Y. Enhancing CD8 T-cell memory by modulating fatty acid metabolism. Nature. 2009;460:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature08097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Araki K, Turner AP, Shaffer VO, Gangappa S, Keller SA, Bachmann MF, Larsen CP, Ahmed R. mTOR regulates memory CD8 T-cell differentiation. Nature. 2009;460:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature08155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao RR, Li Q, Odunsi K, Shrikant PA. The mTOR kinase determines effector versus memory CD8+ T cell fate by regulating the expression of transcription factors T-bet and Eomesodermin. Immunity. 2010;32:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell JD, Delgoffe GM. The mammalian target of rapamycin: linking T cell differentiation, function, and metabolism. Immunity. 2010;33:301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woodland DL. Jump-starting the immune system: prime-boosting comes of age. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masopust D. Developing an HIV cytotoxic T-lymphocyte vaccine: issues of CD8 T-cell quantity, quality and location. J. Intern. Med. 2009;265:125–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Araki K, Ahmed R. From vaccines to memory and back. Immunity. 2010;33:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butler NS, Nolz JC, Harty JT. Immunologic considerations for generating memory CD8 T cells through vaccination. Cell Microbiol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jabbari A, Harty JT. Secondary memory CD8+ T cells are more protective but slower to acquire a central-memory phenotype. J Exp Med. 2006;203:919–932. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masopust D, Ha SJ, Vezys V, Ahmed R. Stimulation history dictates memory CD8 T cell phenotype: implications for prime-boost vaccination. J Immunol. 2006;177:831–839. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wirth TC, Xue HH, Rai D, Sabel JT, Bair T, Harty JT, Badovinac VP. Repetitive antigen stimulation induces stepwise transcriptome diversification but preserves a core signature of memory CD8(+) T cell differentiation. Immunity. 2010;33:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim SK, Reed DS, Olson S, Schnell MJ, Rose JK, Morton PA, Lefrançois L. Generation of mucosal cytotoxic T cells against soluble protein by tissue-specific environmental and costimulatory signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:10814–10819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pope C, Kim S-K, Marzo A, Masopust D, Williams K, Jiang J, Shen H, Lefrançois L. Organ-specific regulation of the CD8 T cell response to Listeria monocytogenes infection. J. Immunol. 2001;166:3402–3409. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altman JD, Moss PAH, Goulder PJR, Barouch DH, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Bell JI, McMichael AJ, Davis MM. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science. 1996;274:94–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masopust D, Vezys V, Marzo AL, Lefrançois L. Preferential localization of effector memory cells in nonlymphoid tissue. Science. 2001;291:2413–2417. doi: 10.1126/science.1058867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Obar JJ, Khanna KM, Lefrancois L. Endogenous naive CD8+ T cell precursor frequency regulates primary and memory responses to infection. Immunity. 2008;28:859–869. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moon JJ, Chu HH, Pepper M, McSorley SJ, Jameson SC, Kedl RM, Jenkins MK. Naive CD4(+) T cell frequency varies for different epitopes and predicts repertoire diversity and response magnitude. Immunity. 2007;27:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mescher MF, Curtsinger JM, Agarwal P, Casey KA, Gerner M, Hammerbeck CD, Popescu F, Xiao Z. Signals required for programming effector and memory development by CD8+ T cells. Immunol. Rev. 2006;211:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarkar S, Teichgraber V, Kalia V, Polley A, Masopust D, Harrington LE, Ahmed R, Wherry EJ. Strength of stimulus and clonal competition impact the rate of memory CD8 T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2007;179:6704–6714. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curtsinger JM, Johnson CM, Mescher MF. CD8 T cell clonal expansion and development of effector function require prolonged exposure to antigen, costimulation, and signal 3 cytokine. J Immunol. 2003;171:5165–5171. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Curtsinger JM, Valenzuela JO, Agarwal P, Lins D, Mescher MF. Type I IFNs provide a third signal to CD8 T cells to stimulate clonal expansion and differentiation. J Immunol. 2005;174:4465–4469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolumam GA, Thomas S, Thompson LJ, Sprent J, Murali-Krishna K. Type I interferons act directly on CD8 T cells to allow clonal expansion and memory formation in response to viral infection. J Exp. Med. 2005;202:637–650. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson LJ, Kolumam GA, Thomas S, Murali-Krishna K. Innate inflammatory signals induced by various pathogens differentially dictate the IFN-I dependence of CD8 T cells for clonal expansion and memory formation. J Immunol. 2006;177:1746–1754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aichele P, Unsoeld H, Koschella M, Schweier O, Kalinke U, Vucikuja S. CD8 T cells specific for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus require type I IFN receptor for clonal expansion. J Immunol. 2006;176:4525–4529. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keppler SJ, Theil K, Vucikuja S, Aichele P. Effector T-cell differentiation during viral and bacterial infections: Role of direct IL-12 signals for cell fate decision of CD8(+) T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009;39:1774–1783. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agnello D, Lankford CS, Bream J, Morinobu A, Gadina M, O’Shea JJ, Frucht DM. Cytokines and transcription factors that regulate T helper cell differentiation: new players and new insights. J. Clin. Immunol. 2003;23:147–161. doi: 10.1023/a:1023381027062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bachmann M, Dragoi C, Poleganov MA, Pfeilschifter J, Muhl H. Interleukin-18 directly activates T-bet expression and function via p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-kappaB in acute myeloid leukemia-derived predendritic KG-1 cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007;6:723–731. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takeda A, Hamano S, Yamanaka A, Hanada T, Ishibashi T, Mak TW, Yoshimura A, Yoshida H. Cutting edge: role of IL-27/WSX-1 signaling for induction of T-bet through activation of STAT1 during initial Th1 commitment. J. Immunol. 2003;170:4886–4890. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.4886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lighvani AA, Frucht DM, Jankovic D, Yamane H, Aliberti J, Hissong BD, Nguyen BV, Gadina M, Sher A, Paul WE, O’Shea JJ. T-bet is rapidly induced by interferon-gamma in lymphoid and myeloid cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:15137–15142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261570598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Afkarian M, Sedy JR, Yang J, Jacobson NG, Cereb N, Yang SY, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. T-bet is a STAT1-induced regulator of IL-12R expression in naive CD4+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:549–557. doi: 10.1038/ni794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seder RA, Darrah PA, Roederer M. T-cell quality in memory and protection: implications for vaccine design. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:247–258. doi: 10.1038/nri2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Way SS, Havenar-Daughton C, Kolumam GA, Orgun NN, Murali-Krishna K. IL-12 and type-I IFN synergize for IFN-gamma production by CD4 T cells, whereas neither are required for IFN-gamma production by CD8 T cells after Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 2007;178:4498–4505. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hamann D, Baars PA, Rep MH, Hooibrink B, Kerkhof-Garde SR, Klein MR, van Lier RA. Phenotypic and functional separation of memory and effector human CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:1407–1418. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401:708–712. doi: 10.1038/44385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Obar JJ, Lefrancois L. Early signals during CD8+ T cell priming regulate the generation of central memory cells. J. Immunol. 2010;185:263–272. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Opferman JT, Ober BT, Ashton-Rickardt PG. Linear differentiation of cytotoxic effectors into memory T lymphocytes. Science. 1999;283:1745–1748. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5408.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jacob J, Baltimore D. Modelling T-cell memory by genetic marking of memory T cells in vivo. Nature. 1999:593–597. doi: 10.1038/21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bannard O, Kraman M, Fearon DT. Secondary replicative function of CD8+ T cells that had developed an effector phenotype. Science. 2009;323:505–509. doi: 10.1126/science.1166831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahmed R, Gray D. Immunological memory and protective immunity: understanding their relation. Science. 1996;272:54–60. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaech SM, Wherry EJ. Heterogeneity and cell-fate decisions in effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation during viral infection. Immunity. 2007;27:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lefrancois L, Masopust D. The road not taken: memory T cell fate ‘decisions’. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:369–370. doi: 10.1038/ni0409-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Macleod MK, McKee AS, David A, Wang J, Mason R, Kappler JW, Marrack P. Vaccine adjuvants aluminum and monophosphoryl lipid A provide distinct signals to generate protective cytotoxic memory CD8 T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:7914–7919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104588108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Turner DL, Cauley LS, Khanna KM, Lefrancois L. Persistent antigen presentation after acute vesicular stomatitis virus infection. J Virol. 2007;81:2039–2046. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02167-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ichii H, Sakamoto A, Kuroda Y, Tokuhisa T. Bcl6 acts as an amplifier for the generation and proliferative capacity of central memory CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2004;173:883–891. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Intlekofer AM, Takemoto N, Wherry EJ, Longworth SA, Northrup JT, Palanivel VR, Mullen AC, Gasink CR, Kaech SM, Miller JD, Gapin L, Ryan K, Russ AP, Lindsten T, Orange JS, Goldrath AW, Ahmed R, Reiner SL. Effector and memory CD8+ T cell fate coupled by T-bet and eomesodermin. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:1236–1244. doi: 10.1038/ni1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rutishauser RL, Martins GA, Kalachikov S, Chandele A, Parish IA, Meffre E, Jacob J, Calame K, Kaech SM. Transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 promotes CD8(+) T cell terminal differentiation and represses the acquisition of central memory T cell properties. Immunity. 2009;31:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oestreich KJ, Huang AC, Weinmann AS. The lineage-defining factors T-bet and Bcl-6 collaborate to regulate Th1 gene expression patterns. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:1001–1013. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jeannet G, Boudousquie C, Gardiol N, Kang J, Huelsken J, Held W. Essential role of the Wnt pathway effector Tcf-1 for the establishment of functional CD8 T cell memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:9777–9782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914127107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhou X, Yu S, Zhao DM, Harty JT, Badovinac VP, Xue HH. Differentiation and persistence of memory CD8(+) T cells depend on T cell factor 1. Immunity. 2010;33:229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilson DC, Matthews S, Yap GS. IL-12 signaling drives CD8+ T cell IFN-gamma production and differentiation of KLRG1+ effector subpopulations during Toxoplasma gondii Infection. J. Immunol. 2008;180:5935–5945. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pham NL, Badovinac VP, Harty JT. Differential role of “signal 3” inflammatory cytokines in regulating CD8 T cell expansion and differentiation in vivo. Frontiers in Immunology. 2011;2 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00004. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pflanz S, Timans JC, Cheung J, Rosales R, Kanzler H, Gilbert J, Hibbert L, Churakova T, Travis M, Vaisberg E, Blumenschein WM, Mattson JD, Wagner JL, To W, Zurawski S, McClanahan TK, Gorman DM, Bazan JF, de Waal MR, Rennick D, Kastelein RA. IL-27, a heterodimeric cytokine composed of EBI3 and p28 protein, induces proliferation of naive CD4(+) T cells. Immunity. 2002;16:779–790. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00324-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Badovinac VP, Porter BB, Harty JT. CD8+ T cell contraction is controlled by early inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:809–817. doi: 10.1038/ni1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Badovinac VP, Messingham KA, Jabbari A, Haring JS, Harty JT. Accelerated CD8+ T-cell memory and prime-boost response after dendritic-cell vaccination. Nat. Med. 2005;11:748–756. doi: 10.1038/nm1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Szabo SJ, Sullivan BM, Peng SL, Glimcher LH. Molecular mechanisms regulating Th1 immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003;21:713–758. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.140942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Whitmire JK, Tan JT, Whitton JL. Interferon-gamma acts directly on CD8+ T cells to increase their abundance during virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:1053–1059. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sanjabi S, Mosaheb MM, Flavell RA. Opposing effects of TGF-beta and IL-15 cytokines control the number of short-lived effector CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;31:131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kuwajima S, Sato T, Ishida K, Tada H, Tezuka H, Ohteki T. Interleukin 15-dependent crosstalk between conventional and plasmacytoid dendritic cells is essential for CpG-induced immune activation. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:740–746. doi: 10.1038/ni1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sanchez PJ, McWilliams JA, Haluszczak C, Yagita H, Kedl RM. Combined TLR/CD40 stimulation mediates potent cellular immunity by regulating dendritic cell expression of CD70 in vivo. J. Immunol. 2007;178:1564–1572. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Salek-Ardakani S, Moutaftsi M, Crotty S, Sette A, Croft M. OX40 drives protective vaccinia virus-specific CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:7969–7976. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu MA. Immunologic basis of vaccine vectors. Immunity. 2010;33:504–515. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wirth TC, Martin MD, Starbeck-Miller G, Harty JT, Badovinac VP. Secondary CD8(+) T-cell responses are controlled by systemic inflammation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011;41:1321–1333. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Araki Y, Wang Z, Zang C, Wood WH, III, Schones D, Cui K, Roh TY, Lhotsky B, Wersto RP, Peng W, Becker KG, Zhao K, Weng NP. Genome-wide analysis of histone methylation reveals chromatin state-based regulation of gene transcription and function of memory CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;30:912–925. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hu JK, Kagari T, Clingan JM, Matloubian M. PNAS Plus: Expression of chemokine receptor CXCR3 on T cells affects the balance between effector and memory CD8 T-cell generation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:E118–E127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101881108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Iwai Y, Hemmi H, Mizenina O, Kuroda S, Suda K, Steinman RM. An IFN-gamma-IL-18 signaling loop accelerates memory CD8+ T cell proliferation. PLoS. One. 2008;3:e2404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Heffner M, Fearon DT. Loss of T cell receptor-induced Bmi-1 in the KLRG1(+) senescent CD8(+) T lymphocyte. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:13414–13419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706040104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]