Abstract

Objective

To investigate risk factors associated with esotropia or exotropia in infants and young children.

Design

Population-based cross-sectional prevalence study.

Participants

Population-based samples of 9970 children ages 6 to 72 months from California and Maryland.

Methods

Participants were preschool African-American, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white children participating in the Multiethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study and the Baltimore Eye Disease Study. Data were obtained by parental interview and ocular examination. Odd ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated to evaluate the association of demographic, behavioral, and clinical risk factors with esotropia and exotropia.

Main Outcome Measures

Odds ratios (ORs) for various risk factors associated with esotropia or exotropia diagnosis based on cover testing.

Results

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, esotropia was independently associated with prematurity, maternal smoking during pregnancy, older preschool age (48–72 months), anisometropia, and hyperopia. There was a severity-dependent association of hyperopia with the prevalence of esotropia, with ORs increasing from 6.4 for 2.00 Diopters (D) to <3.00 D of hyperopia, to 122.0 for ≥ 5.00 D. Exotropia was associated with prematurity, maternal smoking during pregnancy, family history of strabismus, female sex, astigmatism (OR 2.5 for 1.50 to <2.50 D, and 5.9 for ≥ 2.5 D of astigmatism), and aniso-astigmatism in the J0 component (OR ≥ 2 for J0 aniso-astigmatism ≥ 0.25 D).

Conclusions

Prematurity and maternal smoking during pregnancy are associated with a higher risk of having esotropia and exotropia. Refractive error is associated in a severity-dependent manner to the prevalence of esotropia and exotropia. Because refractive error is correctable, these risk associations should be considered when developing guidelines for the screening and management of refractive error in infants and young children children.

Strabismus, a manifest misalignment of the eyes, is a common childhood ocular disorder that often results in vision loss from amblyopia and impaired binocular depth perception. In addition to the functional effects of strabismus, there are often aesthetic concerns that can contribute to psychosocial difficulties in terms of self-image,1–3 interpersonal relationships,4 and social prejudice.5–7 Many patients with strabismus undergo surgical correction or lengthy therapy in hopes of improved ocular alignment and/or attainment of better sensorimotor fusion.

Only recently have population-based age- and ethnicity-specific prevalence estimates for strabismus become available for young children in the United States (US), with overall rates among different ethnic groups ranging from 2.1% to 3.3% in children less than 6 years of age.8, 9 The etiology of childhood strabismus is not well understood, but it is likely that both genetic and environmental factors contribute.

Various early life factors, such as hyperopia,10 have been reported or postulated to be associated with strabismus, yet there is limited contemporary population-based data that have explored the effect of these influences on the development of childhood strabismus while controlling for confounding risk factors. Identifying risk factors for strabismus, especially modifiable ones, has public health significance. This is particularly important in view of the potential long-term consequences of vision loss and depth perception, as well as the psychosocial ramifications of persistent strabismus.1–3

Eye care providers have long been aware of an association between refractive error and certain forms of strabismus. For example, refractive accommodative esotropia, the most prevalent type of esotropia in the US,11, 12 is a well-characterized consequence of childhood hyperopia.13, 14 However, the degree of increased risk associated with different degrees of hyperopia, and the extent to which other types of ametropia pose a risk for strabismus is not known. Defining these relationships is important in that it can help guide eye care providers in the management of childhood refractive error, inform developers of refractive error-based screening instruments as to the thresholds of refractive error that need to be detected, and influence public health policymakers with regard to refractive error-based screening referral thresholds. Using population-based data to establish the level of risk is preferable to data derived from clinical populations because of the inherent referral bias and overrepresentation of disease found in clinical centers.

The objective of the present study is to quantify risk associations, particularly refractive error, for horizontal strabismus in an ethnically diverse cohort of children aged 6 to 72 months enrolled in the population-based Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study (MEPEDS) and Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study (BPEDS).

Methods

The study population comprised 9970 participants 6 to 72 months of age enrolled in two population-based cross-sectional studies – the MEPEDS in southern California and the BPEDS in and around the city of Baltimore, Maryland. The study population, recruitment, cross-site standardization and certification procedures, and an overview of the interview and ocular examination, including details of cycloplegic refraction procedures, are described in a companion paper15 and prior publications.16, 17 A parent or guardian of each participant gave written informed consent. The Institutional Review Board, ethics, privacy, and study oversight statements for this report are identical to our statements in a companion paper.15 Methodological details specific to the present study are included herein.

Clinic Interview and Ocular Examination

Trained interviewers conducted standardized parental interviews in the clinic and optometrists or ophthalmologists, trained and certified using standardized protocols conducted comprehensive eye examinations.15–17 The ocular examination, described in detail elsewhere,8, 16, 17 included monocular distance visual acuity testing for children ≥ 30 months, using single-surrounded HOTV opotypes on the electronic visual acuity tester18 according to the Amblyopia Treatment Study protocol,19 using naming or matching of letters;20, 21 fixation preference testing;22, 23 evaluation of ocular alignment; anterior segment and dilated fundus evaluations, and measurement of refractive error under cycloplegic conditions.15 Vector analysis was used to determine the J0 (power in the vertical or horizontal meridian) and J45 (power in the oblique meridian) vector components of astigmatism.24, 25

Determination of Strabismus

Ocular alignment was evaluated using the unilateral cover (cover-uncover) test and alternate cover and prism test, at distance and near fixation, without correction and with optical correction if worn. Transient misalignment after alternate cover testing was not designated as strabismus unless confirmed by a repeat unilateral cover test. Strabismus was classified according to the primary direction (esotropia, exotropia, vertical) of the tropia. Hirschberg testing was used when cover testing could not be performed. Strabismus was defined as constant or intermittent heterotropia of any magnitude at distance and/or near fixation. Children tested at only one fixation distance and found to be without strabismus were considered non-strabismic.

Statistical Analysis

Potential risk factors were based on previously reported associations with strabismus or plausible prior hypotheses. Demographic, behavioral, and clinical factors evaluated for each child are detailed in a companion paper15 and found in Table 1. Ocular risk factors were bilateral spherical equivalent (SE) refractive error (SE of less hyperopic eye), bilateral astigmatism (absolute astigmatism of less astigmatic eye), SE anisometropia, J0 anisometropia (interocular difference in J0), and J45 anisometropia (interocular difference in J45); the dioptric criteria for levels of magnitude are provided in Table 2. The less hyperopic eye was chosen for SE refractive error analysis because if anisometropia is present, accommodative convergence (a potential contributor to convergent strabismus) is likely to be driven by accommodation in the less hyperopic eye.

Table 1.

Frequency distributions of demographic, behavioral, and clinical risk factors in children with and without strabismus in the MEPEDS and BPEDS

| Risk Factor | Esotropia (N=102) n (%)* | No Esotropia (N=8389) n (%)* | P Value** | Exotropia (N=102) n (%)* | No Exotropia (N=8389) n (%)* | P Value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (months) | <0.0001 | 0.03 | ||||

| 06–11 | 2 (0.3) | 796 (99.7) | 7 (0.9) | 791 (99.1) | ||

| 12–23 | 10 (0.7) | 1485 (99.3) | 10 (0.7) | 1485 (99.3) | ||

| 24–35 | 13 (0.8) | 1541 (99.2) | 14 (0.9) | 1540 (99.1) | ||

| 36–47 | 16 (1.1) | 1512 (98.9) | 20 (1.3) | 1508 (98.7) | ||

| 48–59 | 29 (1.9) | 1533 (98.1) | 30 (1.9) | 1532 (98.1) | ||

| 60–72 | 32 (2.1) | 1522 (97.9) | 21 (1.4) | 1533 (98.6) | ||

| Sex: Female | 48 (1.2) | 4060 (98.8) | 0.79 | 61 (1.5) | 4047 (98.5) | 0.02*** |

| Race/Ethnic Group | 0.03 | 0.61 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 33 (1.8) | 1828 (98.2) | 20 (1.1) | 1841 (98.9) | ||

| African American | 41 (1.1) | 3563 (98.9) | 41 (1.1) | 3563 (98.9) | ||

| Hispanic | 28 (0.9) | 2998 (99.1) | 41 (1.4) | 2985 (98.6) | ||

| Study site | 0.96 | 0.52 | ||||

| MEPEDS | 78 (1.2) | 6435 (98.8) | 81 (1.2) | 6432 (98.8) | ||

| BPEDS | 24 (1.2) | 1954 (98.8) | 21 (1.1) | 1957 (98.9) | ||

| Caregiver education <High school diploma/GED† | 25 (1.0) | 2385 (99.0) | 0.35 | 33 (1.4) | 2377 (98.6) | 0.41 |

| Household income < $20,000/yr† | 59 (1.4) | 4137 (98.6) | 0.16 | 55 (1.3) | 4141 (98.7) | 0.19 |

| Health Insurance† | 95 (1.2) | 8049 (98.8) | 0.13 | 97 (1.2) | 8047 (98.8) | 0.60 |

| Vision Insurance† | 65 (1.6) | 3971 (98.4) | 0.003 | 47 (1.2) | 3989 (98.8) | 0.41 |

| Last routine medical exam <2yrs† | 101 (1.2) | 8232 (98.8) | 0.38 | 99 (1.2) | 8234 (98.8) | 0.37 |

| Limited access to health care† | 16 (1.4) | 1155 (98.6) | 0.56 | 18 (1.5) | 1153 (98.5) | 0.32 |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 19 (2.6) | 725 (97.4) | 0.0004 | 23 (3.1) | 721 (96.9) | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol during pregnancy† | 3 (1.2) | 252 (98.8) | 1.000 | 5 (2.0) | 250 (98.0) | 0.24 |

| History of breastfeeding† | 59 (1.0) | 5634 (99.0) | 0.06 | 59 (1.0) | 5634 (99.0) | 0.05 |

| Maternal age at childbirth ≥35 yrs† | 17 (1.6) | 1042 (98.4) | 0.20 | 17 (1.6) | 1042 (98.4) | 0.20 |

| Gestational age (weeks)† | 0.0002†† | 0.01†† | ||||

| <33 | 11 (4.4) | 237 (95.6) | 8 (3.2) | 240 (96.8) | ||

| 33 to <37 | 9 (1.6) | 540 (98.4) | 9 (1.6) | 540 (98.4) | ||

| 37 to <42 | 78 (1.1) | 7261 (98.9) | 81 (1.1) | 7258 (98.9) | ||

| ≥42 | 4 (1.1) | 351 (98.9) | 4 (1.1) | 351 (98.9) | ||

| Small for gestational age† | 16 (1.0) | 1567 (99.0) | 0.55 | 21 (1.3) | 1562 (98.7) | 0.65 |

| Down syndrome† | 1 (6.3) | 15 (93.7) | 0.18 | 0 (0.0) | 16 (100.0) | 1.00 |

| Cerebral palsy† | 2 (16.7) | 10 (83.3) | 0.009 | 3 (25.0) | 9 (75.0) | 0.0003 |

| Family history of strabismus† | 15 (2.9) | 496 (97.1) | 0.0002 | 14 (2.7) | 497 (97.3) | 0.0006 |

| Family history of amblyopia† | 2 (1.7) | 116 (98.3) | 0.61 | 3 (2.5) | 115 (97.5) | 0.17 |

MEPEDS: Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study, BPEDS: Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study, Yrs: years, GED: General Educational Development test

Percentage of participants with stated level of risk factor,

Chi square or Fisher’s exact test where applicable,

Sex was associated with exotropia at the univariate level only in the restricted, final model dataset, not in the overall dataset, and was therefore not considered in the final model in the primary analysis.

Denominators (number of participants with stated outcome status) for this variable differ from other variables because of missing data.

P value for dichotomous categorization (<33 weeks; ≥33 weeks).

Table 2.

Frequency distributions of refractive error risk factors in 6- to 72-month-old children with and without strabismus in the MEPEDS and BPEDS

| Risk Factor | Esotropia (N=102) n (%)* | No Esotropia (N=8389) n (%)* | P Value | Exotropia (N=102) n (%)* | No Exotropia (N=8389) n (%)* | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE Anisometropia (D) | <0.0001 | 0.004 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| <0.50 | 64 (1.0) | 6546 (99.0) | 72 (1.1) | 6538 (98.9) | ||

| 0.50 to <1.00 | 21 (1.4) | 1496 (98.6) | 19 (1.3) | 1498 (98.7) | ||

| ≥1.00 | 17 (4.7) | 347 (95.3) | 11 (3.0) | 353 (97.0) | ||

|

| ||||||

| J0 Anisometropia (D) | 0.03 | <0.0001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| <0.25 | 74 (1.1) | 6938 (98.9) | 67 (1.0) | 6945 (99.0) | ||

| 0.25 to <0.50 | 23 (1.9) | 1165 (98.1) | 26 (2.2) | 1162 (97.8) | ||

| ≥0.50 | 5 (1.7) | 286 (98.3) | 9 (3.1) | 282 (96.9) | ||

|

| ||||||

| J45 Anisometropia (D) | 0.007 | <0.0001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| <0.25 | 68 (1.0) | 6623 (99.0) | 72 (1.1) | 6619 (98.9) | ||

| 0.25 to <0.50 | 20 (1.7) | 1150 (98.3) | 10 (0.9) | 1160 (99.1) | ||

| ≥0.50 | 14 (2.2) | 616 (97.8) | 20 (3.2) | 610 (96.8) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Astigmatism** (D) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| <0.50 | 44 (0.9) | 5148 (99.1) | 49 (0.9) | 5143 (99.1) | ||

| 0.50 to <1.00 | 26 (1.3) | 2020 (98.7) | 19 (0.9) | 2027 (99.1) | ||

| 1.00 to <1.50 | 18 (2.6) | 685 (97.4) | 13 (1.9) | 690 (98.1) | ||

| 1.50 to <2.50 | 12 (2.9) | 407 (97.1) | 12 (2.9) | 407 (97.1) | ||

| ≥2.50 D | 2 (1.5) | 129 (98.5) | 9 (6.9) | 122 (93.1) | ||

|

| ||||||

| SE Refractive Error** (D) | <0.0001† | 0.001† | ||||

|

| ||||||

| ≤ −1.00 | 3 (0.8) | 398 (99.2) | 13 (3.2) | 388 (96.8) | ||

| > −1.00 to < 0.00 | 5 (0.5) | 1007 (99.5) | 14 (1.4) | 998 (98.6) | ||

| 0.00 to < +1.00 | 7 (0.2) | 2907 (99.8) | 34 (1.2) | 2880 (98.8) | ||

| +1.00 to < +2.00 | 12 (0.5) | 2651 (99.5) | 29 (1.1) | 2634 (98.9) | ||

| +2.00 to < +3.00 | 14 (1.5) | 905 (98.5) | 5 (0.5) | 914 (99.5) | ||

| +3.00 to < +4.00 | 20 (5.7) | 331 (94.3) | 4 (1.1) | 347 (98.9) | ||

| +4.00 to < +5.00 | 17 (13.1) | 113 (86.9) | 1 (0.8) | 129 (99.2) | ||

| ≥ +5.00 | 24 (23.8) | 77 (76.2) | 2 (2.0) | 99 (98.0) | ||

MEPEDS: Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study; BPEDS: Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study;

D = diopters; SE = Spherical equivalent; J0 =power in the vertical or horizontal meridian; J45 = power in the oblique meridian.

Percentage of participants with stated outcome status,

Level of refractive error defined by the less hyperopic eye for SE refractive error, and the less astigmatic eye for astigmatic refractive error, or by the eye with refractive error data if data are missing for the fellow eye.

P value for esotropia analysis is reported using a single category for all SE refractive errors < 0.00 D; P value for exotropia analysis is reported using a single category for all SE refractive errors ≥ +1.00 D.

Risk factors were explored separately for esotropia and exotropia using univariate analysis; those showing at least marginally significant associations (P<0.1) were considered candidates for subsequent forward stepwise multiple logistic regression (except for Down syndrome and cerebral palsy because of small numbers, and family history of strabismus or amblyopia because of questionable accuracy of parental report). If family history was significant at the univariate level, we explored the sensitivity of the final multivariate model to the addition of family history to the model. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for significant independent risk factors included in the final model. Univariate results are reported using the same restricted dataset as the final model; participants with missing values for any variable included in the final multivariate model were excluded. Formal tests of interaction between selected variables were completed by including a product term in the multivariate model. Further details regarding the statistical analyses and regarding the locally weighted scatter plot smoothing (LOWESS) technique26 used to examine the independent relationship between continuous risk factors and the prevalence of esotropia and exotropia are provided in a companion paper.15

RESULTS

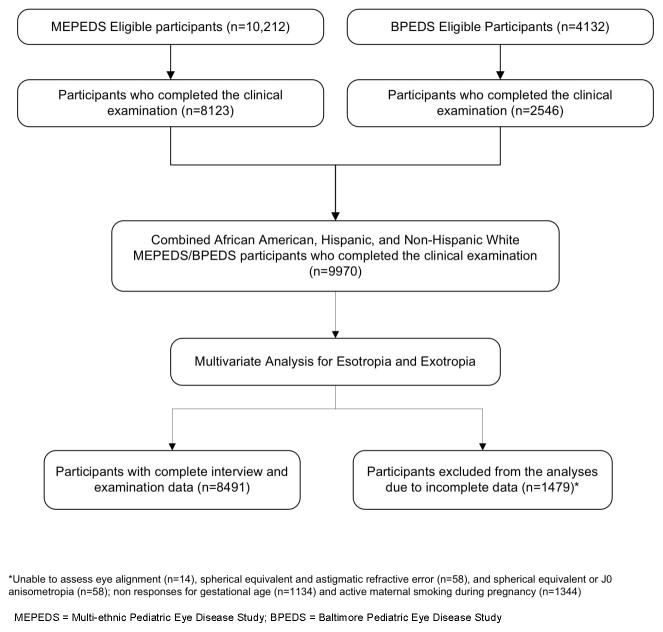

Eighty percent of eligible MEPEDS children and 62% of eligible BPEDS children were examined. Comparison of participants and nonparticipants has been published previously.8, 17 The study population comprised 9970 children who underwent clinical examination (Figure 1). Of these, 4849 (49%) were girls; 4355 (43.7%) were African-American, 3147 (31.6%) were Hispanic, and 2468 (24.8%) were non-Hispanic white. Our multivariate models were based on 8491 participants with complete data for all significant variables (Figure 1), including 102 children with esotropia and 102 with exotropia. There were no significant differences in characteristics of children included in the data analysis compared to those excluded for missing data except for the sex of those with exotropia (P=0.02). Of those excluded, 2.2% of the boys and 1.2% of the girls had exotropia (difference was not significant; P=0.16), in contrast to those analyzed, where 0.9% of boys and 1.5% of girls had exotropia. In MEPEDS, only 19% of strabismic children had ever been treated for strabismus and in BPEDS9 only 27% had been treated previously. The demographic, behavioral, clinical, and refractive error characteristics for those with and without esotropia and those with and without exotropia are provided in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart showing children in the Multi-Ethnic and Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study cohorts who were included and excluded from the final analysis sample for both the esotropia and exotropia outcomes.

Esotropia

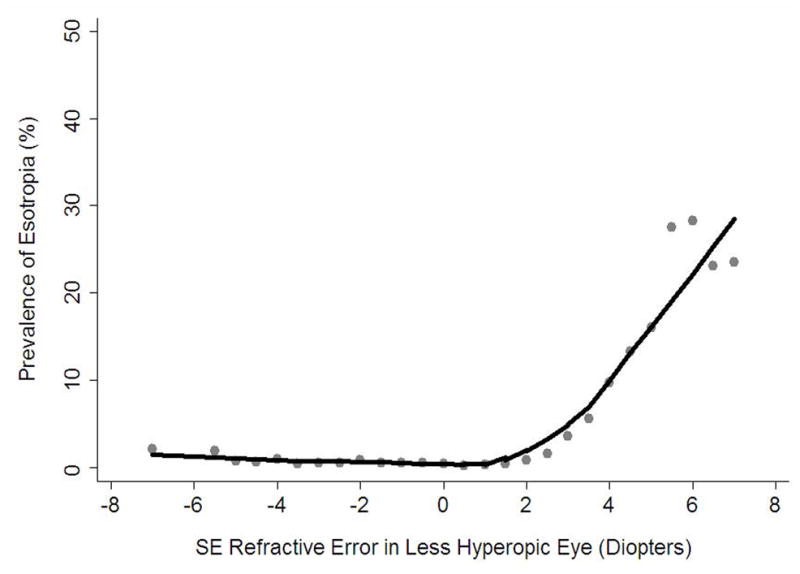

The univariate analysis results for associations between potential risk factors evaluated and esotropia are provided in Tables 1 and 2. After adjustment for the other variables in the multivariate analysis, the following were identified as independent indicators of a greater risk for esotropia: gestational age < 33 weeks (OR=4.43), active maternal smoking during pregnancy (OR=2.04), age range of 48 to 72 months (OR ≥ 7.94 relative to reference age group of 6–11 months), SE anisometropia ≥ 1.00 D (OR=2.03 relative to reference level of <0.50 D), and SE hyperopia starting at the +2.00 to < +3.00 D level (OR ranging from 6.38 to 122.24 for different levels of hyperopia, relative to reference level of 0.00 to < +1.00 D) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Independent Risk Factors† for Childhood Esotropia in 6- to 72-month Old Children in the MEPEDS and BPEDS

| Risk Factor | OR (95% CI)* | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| SE refractive error (D) | <0.0001 | |

| 0.00 to < +1.00 | Reference | |

| < 0.00 (myopia) | 2.48 (0.89 – 6.91) | |

| +1.00 to < +2.00 | 1.81 (0.71 – 4.62) | |

| +2.00 to < +3.00 | 6.38 (2.56 – 15.93) | |

| +3.00 to < +4.00 | 23.06 (9.56 – 55.61) | |

| +4.00 to < +5.00 | 59.81 (23.61 – 151.52 | |

| ≥ +5.00 | 122.24 (49.86 – 299.70) | |

| Gestational age <33 weeks | 4.43 (2.14 – 9.19) | <0.0001 |

| Age group (months) | 0.0003 | |

| 06–11 | Reference | |

| 12–23 | 2.88 (0.62 – 13.46) | |

| 24–35 | 3.75 (0.83 – 17.04) | |

| 36–47 | 4.03 (0.90 – 17.92) | |

| 48–59 | 7.94 (1.85 – 34.03) | |

| 60–72 | 9.40 (2.20 – 40.10) | |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy | 2.04 (1.17 – 3.56) | 0.01 |

| Spherical equivalent anisometropia (D) | 0.05 | |

| <0.50 | Reference | |

| 0.50 to <1.00 | 0.91 (0.53 – 1.55) | |

| ≥1.00 | 2.03 (1.10 – 3.73) |

MEPEDS: Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study; BPEDS: Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study; OR = Odds ratio; CI = 95% confidence interval; SE = spherical equivalent; D = diopters

Based on multivariate stepwise logistic regression model

Adjusted for all factors listed in the table

OR’s in bold are statistically significant

Having vision insurance was also associated with increased likelihood of esotropia (OR=1.62, 95% CI 1.03–2.55); adjusted for covariates listed above). However, because vision insurance was likely obtained as a consequence of having esotropia, rather than it causing esotropia, vision insurance was not included as a covariate in the final multivariate model. When vision insurance was included, the associations with other variables were qualitatively unchanged, with only minor differences in ORs.

When we explored the sensitivity of the final model to adding the variable of positive family history of strabismus, we found it was associated with greater odds of having esotropia (OR=1.86); however, this association did not reach statistical significance (P=0.054; 95% CI 0.99 – 3.48) or substantively alter the OR’s of any other variables in the final model.

Hyperopia of ≥ +3.00 D was the strongest predictor of esotropia. The LOWESS plot (Figure 2) shows an approximately linear relationship between prevalence of esotropia and SE refractive error starting at a magnitude of hyperopia of +2.00 D and extending beyond, with an essentially flat plot for myopic, emmetropic, and hyperopic refractive error < +2.00D. The LOWESS plot of esotropia prevalence as a function of SE anisometropia shows an increase in risk of esotropia primarily for levels of anisometropia over 1.00 D (Figure 3, available at http://aaojournal.org).

Figure 2.

Locally weighted scatter plot smoothing (LOWESS) plot illustrating the independent relationship between level of spherical equivalent (SE) refractive error and the prevalence of esotropia in 6- to 72-month-old children in the Multi-Ethnic and the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Studies (MEPEDS and BPEDS), after controlling for other risk factors.

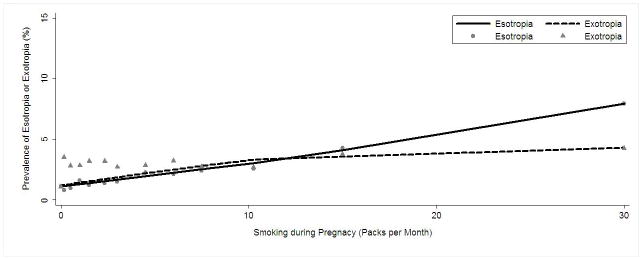

To further explore the relationship between maternal smoking during pregnancy and esotropia, we evaluated the estimated prevalence of esotropia as a function of pack-months of smoking during pregnancy, adjusting for all other significant covariates in the final multivariate model. A LOWESS plot illustrating a linear relationship between amount of smoking and risk of esotropia is shown in Figure 4. We also ran our multivariate model without including refractive error variables as covariates and found only a small increase in the OR for the association of esotropia with maternal smoking as a dichotomous variable (OR=2.34; 95% CI 1.41–3.89).

Figure 4.

Locally weighted scatter plot smoothing (LOWESS) plot illustrating the independent relationship between level of pack-months of maternal smoking during pregnancy and the prevalence of esotropia and exotropia in 6- to 72-month-old children in the Multi-Ethnic and the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Studies (MEPEDS and BPEDS), after controlling for other risk factors.

Including interaction variables in the multivariate model did not reveal any statistically significant interactions between the effects of SE refractive error and age, or between the effects of SE refractive error and SE anisometropia, with regard to increased risk of esotropia.

Subgroup analysis for MEPEDS alone identified a very similar set of independent risk factors, with the following differences: maternal smoking was not independently associated with esotropia, while racial/ethnic group was associated with esotropia (OR=2.84, 95% CI 1.50–5.38 for non-Hispanic white children relative to the Hispanic reference group), as was lack of health insurance (OR=3.71, 95% CI 1.53–9.00). The subgroup analysis for BPEDS alone also yielded similar results, finding significant associations of esotropia with SE refractive error, age group, and maternal smoking, although analysis of BPEDS data did not reveal associations with SE anisometropia or gestational age.

Exotropia

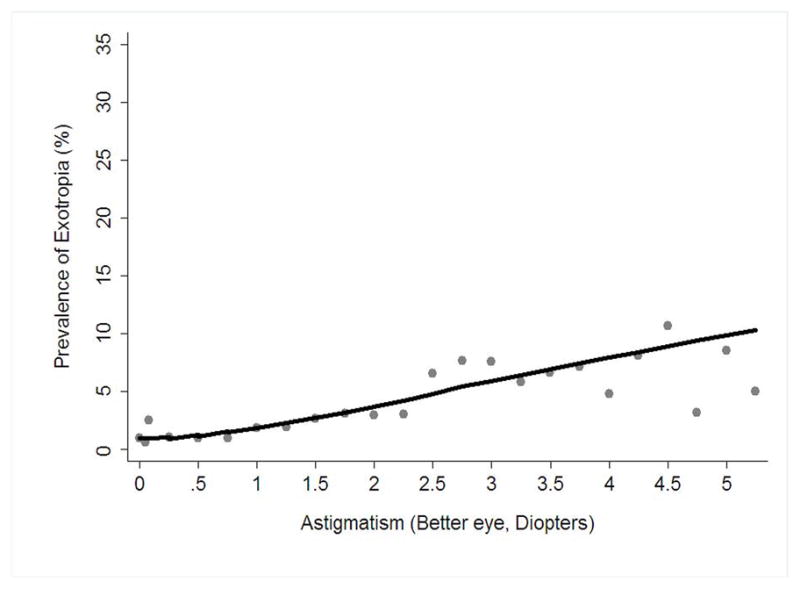

The results of the univariate analysis of associations between potential risk factors and exotropia are shown in Tables 1 and 2. In the multivariate analysis, active maternal smoking during pregnancy, gestational age < 33 weeks, female sex, bilateral astigmatism of ≥ 1.50 D, and J0 anisometropia of at least 0.25 to 0.50 D (equivalent to 0.50 to 1.00 D interocular difference in cylinder amount for a given axis of cylinder) were identified as independent indicators of a greater risk for exotropia after adjustment for the other variables (Table 4).

Table 4.

Independent Risk Factors† for Childhood Exotropia in 6- to 72-Month-Old Children in the MEPEDS and BPEDS

| Risk Factor | OR (95% CI)* | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy | 2.88 (1.78 – 4.64) | <0.0001 |

| Gestational age <33 weeks | 2.48 (1.17 – 5.25) | 0.018 |

| Female sex | 1.62 (1.08 – 2.42) | 0.019 |

| Astigmatism **(D) | <0.0001 | |

| <0.50 | Reference | |

| 0.50 to <1.00 | 0.82 (0.48 – 1.41) | |

| 1.00 to <1.50 | 1.55 (0.82 – 2.91) | |

| 1.50 to <2.50 | 2.49 (1.30 – 4.79) | |

| ≥2.50 | 5.88 (2.76 – 12.54) | |

| J0 Anisometropia (D) | 0.003 | |

| <0.25 | Reference | |

| 0.25 to <0.50 | 2.01 (1.25 – 3.22) | |

| ≥0.50 | 2.63 (1.26 – 5.49) |

MEPEDS: Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study, BPEDS: Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study, OR = Odds ratio; CI = 95% confidence interval; SE = spherical equivalent; D = diopters

Based on multivariate stepwise logistic regression model

Adjusted for all factors listed in the table

OR’s in bold are statistically significant

Level defined by the eye with the lower magnitude of astigmatism

Astigmatism of ≥ 2.50 D was the strongest risk factor, conferring a 6-fold risk for exotropia. A LOWESS plot of the estimated prevalence of exotropia, adjusting for all other significant covariates, shows an approximately linear relationship with the magnitude of astigmatism (Figure 5). The estimated prevalence of exotropia also increases with increasing J0 anisometropia, up to approximately 1.00 D (Figure 6, available at http://aaojournal.org).

Figure 5.

Locally weighted scatter plot smoothing (LOWESS) plot illustrating the independent relationship between magnitude of astigmatism and the prevalence of exotropia in 6- to 72-month-old children in the Multi-Ethnic and the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Studies (MEPEDS and BPEDS), after controlling for other risk factors.

To further explore the relationship between maternal smoking during pregnancy and exotropia, we evaluated the estimated prevalence of exotropia, adjusted for all other significant covariates in the final multivariate model, as a function of pack-months of smoking during pregnancy. A LOWESS plot illustrating the linear relationship between amount of smoking and risk of exotropia is shown in Figure 4. We also ran our multivariate model without refractive error variables as covariates and found only a small increase in the OR for the association of exotropia with maternal smoking as a dichotomous variable (OR=3.02; 95% CI 1.89–4.85).

Subgroup analyses for MEPEDS alone identified the same set of independent risk factors for exotropia, as well as an increased risk of exotropia with SE myopia of ≥ 1.00 D in at least one eye (OR=2.46, 95% CI 1.17–5.16, relative to group having 0.00 to < +1.00 D of SE refractive error in the less hyperopic eye). Subgroup analysis for BPEDS alone showed increased risk of exotropia with maternal smoking during pregnancy and gestational age, as well as two risk factors that were not significant in the combined analysis: being small for gestational age (OR=4.08, 95% CI 1.69–9.85), and lacking health insurance (OR=4.95, 95% CI 1.05–23.30).

When we explored the sensitivity of the final model to adding the variable for positive family history of strabismus, we found it to be independently associated with a greater risk for exotropia (OR=2.29; 95% CI 1.27 – 4.13; P=0.006). Adding this variable did not substantively alter the significance or the OR’s of any of the other variables in the final model.

DISCUSSION

The present study used a large population-based and ethnically diverse cohort of children aged 6 to 72 months to identify independent risk factors for childhood esotropia and exotropia. The major potentially modifiable or correctable risk factors for esotropia were hyperopic and anisometropic refractive error and maternal smoking during pregnancy; gestation <33 weeks and older age (range of 48–72 months) also conferred a higher risk. For exotropia, maternal smoking during pregnancy, shortened gestation, female sex, and family history of strabismus were independent risk factors, as was astigmatic refractive error and anisometropia with regard to the J0 component of astigmatism.

Maternal smoking during pregnancy was associated with both esotropia and exotropia. Previous studies, with one exception,27 have found an association with esotropia, but not exotropia.28–32 However, in no previous study were strabismus diagnoses based on standardized comprehensive eye examinations of a population-based cohort. We found the likelihood of strabismus increased with the average daily number of cigarettes smoked by the pregnant mother, supporting prior reports of a dose-response effect.27, 28

Maternal smoking is also associated with hyperopia15 and astigmatism33 which are themselves risk factors for strabismus. Many previous studies investigating perinatal factors and strabismus have not adjusted for refractive error, making it difficult to determine whether the impact of smoking is direct or is indirect via refractive error. By adjusting for refractive error, we have shown that smoking is independently related to strabismus. Furthermore, excluding refractive errors from the multivariate models did not greatly alter the odds ratios for maternal smoking, suggesting that most of the effect of smoking is not mediated through its effects on refractive development. Maternal smoking during pregnancy is also known to be associated with shortened gestation and impaired fetal growth,34, 35 which are themselves risk factors for strabismus. However, our analysis adjusted for preterm delivery and being small for gestational age, demonstrating an independent association between maternal smoking and strabismus.

The mechanism linking prenatal exposure to tobacco with strabismus or other adverse outcomes is unknown. Because the fetus is directly exposed through the placenta,36 there could be direct toxic effects on the developing nervous system, similar to other neuro-developmental disorders known to be caused by environmental neurotoxins like tobacco.37–40

Hyperopia was a strong predictor of esotropia. Although esotropia is known to occur more frequently in children with hyperopia than in those without,41–43 and infants with moderate hyperopia are more likely to develop subsequent esotropia than emmetropic controls,10, 44–47 evidence-based data quantifying the risk associated with different levels of hyperopia are nonexistent. The hyperopia thresholds currently recommended for vision screening failure48 and refractive correction49, 50 are based only on consensus. Our data show that levels of hyperopia lower than these, between +2.00 and <+3.00 D, pose more than a 6-fold increase in esotropia risk, although the prevalence of esotropia at this level of hyperopia is modest at <2%. There is a marked rise in esotropia risk associated with each diopter of increasing hyperopia (Figure 2). With hyperopia ≥ +5.00 D, esotropia is seen in 24% of cases, and the odds of having esotropia are 122 times greater than in children with 0 to <+1.00 D of hyperopia. Some of the non-strabismic children in this cross-sectional study may still be at risk of developing esotropia in the future, so the association between hyperopia and esotropia needs to be further evaluated in longitudinal studies. In addition, randomized clinical trials are needed to determine to what extent the treatment of hyperopia might prevent esotropia. In the meantime, eye care providers and parents can use our data on the degree of increased risk associated with differing levels of hyperopia to make more informed decisions regarding the management of individual children with hyperopia (i.e., whether to monitor or provide optical correction), understanding, however, that the benefits of prophylactic spectacle treatment have yet to be proven.

While our data indicate that esotropia risk is much greater for high levels of hyperopia than for moderate hyperopia, many fewer children are at risk from high hyperopia because it is much less prevalent.51, 52 Consequently, it is difficult to identify a single threshold level of hyperopia that is optimal as a criterion for referral of children at risk of esotropia or for consideration of prophylactic spectacle prescription. For example, as seen from the frequency distributions in Table 2, the lowest dioptric criterion that confers significant increased risk of esotropia (i.e.,+ ≥ 2.00 D), identifies nearly 18% of our cohort as being at risk, 95% of whom do not have esotropia; on the other hand, a majority (74%) of esotropic children would be identified. In contrast, a more conservative criterion similar to that proposed by consensus guidelines (≥ + 4.00 D)49, 50 targets a more manageable 3% of the population, with a substantial yield (18%) of esotropia in the targeted group; however, fewer than half (40%) of all children with esotropia would be identified. Thus, our cross-sectional data do not support the existence of a hyperopia cut-off that is both sensitive and specific for associated esotropia. In any case, longitudinal data relating early refractive error to subsequent eye alignment and vision outcomes at older ages are needed to fully address questions related to screening thresholds. While hyperopia may have some value from a screening perspective as a marker for existing strabismus – because most esotropias are of moderate size8 and can go undetected by primary care providers – its greatest potential value in the screening setting would be as a predictor of future esotropia and/or amblyopia, especially in light of the possible benefits of prophylactic spectacle treatment.10

In the case of exotropia, astigmatism showed a stronger association than did SE refractive error. Exotropia was associated with astigmatism ≥ 1.50 D in the less astigmatic eye. There are few studies with which we can compare this risk association. While astigmatism has previously been noted to be associated with strabismus in general, separate analysis of esotropia and exotropia were not reported.53, 54

We also detected an association between esotropia and SE anisometropia, and between exotropia and aniso-astigmatism in the J0 component, after adjusting for other risk factors. Previous studies have reported associations between anisometropia and strabismus but did not analyze esotropia and exotropia separately.53–55 Data from a hyperopia-enriched clinic population have indicated that coexisting anisometropia increases the risk of esotropia in the presence of hyperopia.56, 57 We tested for, but did not detect, any significant statistical interaction between hyperopia and anisometropia in our analysis of esotropia. Associations between anisometropia and strabismus are highly plausible from a clinical perspective. Anisometropia has been shown to reduce binocularity in patients without strabismus,58, 59 and clinicians view uncorrected anisometropia as a sensory fusion obstacle to normal binocular vision.

Gestational age less than 33 weeks was independently associated with increased risk of both esotropia and exotropia. Several prior studies have reported shortened gestation to be associated with childhood esotropia, exotropia, or strabismus in general.55, 60–65 We are unable to compare our findings directly to these because of differing definitions of prematurity, use of clinical samples as opposed to our population-based cohort, data analyses not adjusted for other potentially confounding risk factors, and non-uniform determination of and definitions of strabismus.

Older preschool age, specifically 48–72 months, conferred an 8- to 9-fold increased risk of esotropia. There was no age association with exotropia. We are not aware of any study showing an independent risk association between older preschool age and esotropia after adjusting for other risk factors. However, longitudinal studies have shown that strabismus is rare in the first year of life.10, 44, 66 We previously reported a higher prevalence of esotropia in 36- to 72-month-old children than in those 6 to 35 months of age,8 and the BPEDS similarly reported a very low prevalence of strabismus among 6- to 11-month-old children.9 These findings are not likely to be an artifact of failure to detect strabismus in younger children because esotropia prevalence increased with age even after excluding small-angle deviations.8 The present analysis adjusting for all other risk factors provides even more robust evidence for a strong relationship between age and esotropia, probably because the most prevalent form of esotropia, accommodative esotropia,11, 12 occurs more commonly when hyperopic children are older and accommodating more consistently.

We found that being female was independently associated with exotropia. While a predominance of girls has been reported among incident cases of intermittent exotropia in children < 19 years of age in a semi-urban white population,67 to our knowledge, ours is the first population-based report that has controlled for confounding variables to find this association.

There was an independent association between positive family history of strabismus and exotropia. These results are consistent with long-held clinical observations68–70 and data from a large cohort study71 that there is a significant familial component in the cause of strabismus. We adjusted for a wide range of confounding factors, in particular refractive error, thus suggesting that the heritability of exotropia is not merely the result of the heritability of refractive error.72

As with many epidemiological investigations, our study has a number of potential limitations. We excluded 1,479 participants from the analysis because of missing data, but we did not find significant differences in characteristics of those included versus those excluded in the analysis, with the exception that among excluded children, female sex was not associated with exotropia. However, when we collapsed the excluded and included into one sample, the univariate association between sex and exotropia was still present, though diminished. We relied on parental report for determination of demographic and behavioral factors. Mothers of children without vision disorders may have selectively under reported smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy. We believe it unlikely that our findings were substantially impacted by recall bias because these questions were just two of many that were asked during a prolonged interview, which preceded the conclusion of the clinical exam with its attendant discussion of ocular findings, and self reports have been shown to be a valid indicator of actual smoking levels.73 We necessarily explored a finite number of potential risk factors. It is possible that other unknown or unexplored factors known to affect development, such as maternal diet during pregnancy and environmental toxins, including maternal secondhand smoke during pregnancy, could also contribute to strabismus. Prior successful treatment of strabismus could potentially mask or underestimate risk associations; however, a minority of our strabismic participants had received prior treatment. Because of the cross-sectional design, we only have confirmation of refractive error and alignment at the time of clinical examination. Thus, for older children it is possible that their refractive error may have been different at an earlier age; and likewise, there may be younger children at risk for strabismus who have yet to develop strabismus, which could lead to underestimation of the strength of associations with refractive error. The cross-sectional design also precludes determination of the temporal relationship between the identified risk factors and strabismus. Thus, longitudinal study is needed to confirm our cross-sectional findings.

The main strengths of our study include the large ethnically diverse cohort of children from two distinct geographical areas in the US and the population-based design. Compared to clinic-based samples that overrepresent severe disease, our study is more likely to be generalizable to the population as a whole, and risk associations are less likely to be spurious. A particular strength is that all children received comprehensive eye examinations by study-certified eye care providers who followed a standardized protocol, determining refractive error by cycloplegic refraction and strabismus by cover testing; thus, misclassifications should be rare. By using multivariate analysis we were able to evaluate the independent impact of a broad range of potential risk factors for strabismus without confounding from coexisting risk factors.

In conclusion, this population-based study of childhood strabismus has established a strong dose-dependent link between refractive errors and strabismus and confirmed the role of other risk factors, such as premature birth and gestational exposure to maternal smoking. Because refractive errors may be targeted for early intervention, our data provide valuable information to help guide providers and patient families in making informed decisions regarding management of early refractive error. However, longitudinal study is needed both to confirm the predictive value of uncorrected refractive error, and to evaluate the potential impact of early treatment.

Supplementary Material

Locally weighted scatter plot smoothing (LOWESS) plot illustrating the independent relationship between magnitude of spherical equivalent (SE) anisometropia and the prevalence of esotropia in 6- to 72-month-old children in the Multi-Ethnic and the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Studies (MEPEDS and BPEDS), after controlling for other risk factors.

Locally weighted scatter plot smoothing (LOWESS) plot illustrating the independent relationship between magnitude of J0 anisometropia and the prevalence of exotropia in 6- to 72-month-old children in the Multi-Ethnic and the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Studies (MEPEDS and BPEDS), after controlling for other risk factors.

Acknowledgments

Support: Supported by the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (grant nos. EY14472, EY03040 and EY14483), and an unrestricted grant from the Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY. Dr. Varma is a Research to Prevent Blindness Sybil B. Harrington Scholar.

The MEPEDS-BPEDS Investigators would like to acknowledge the helpful advice and support of the members of the National Eye Institute’s Data Monitoring and Oversight Committee comprising of: Jonathan M. Holmes, MD (Chair), Eileen Birch, PhD, Karen Cruickshanks, PhD, Natalie Kurinij, PhD, Maureen Maguire, PhD, Joseph Miller, MD, MPH, Graham Quinn, MD, and Karla Zadnik, OD, PhD.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed in the manuscript.

“This article contains online-only material. The following should appear online-only: Figures 3 and 6.”

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Satterfield D, Keltner JL, Morrison TL. Psychosocial aspects of strabismus study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:1100–5. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090080096024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bez Y, Coskun E, Erol K, et al. Adult strabismus and social phobia: a case-controlled study. J AAPOS. 2009;13:249–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson S, Harrad RA, Morris M, Rumsey N. The psychosocial benefits of corrective surgery for adults with strabismus. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:883–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.089516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mojon-Azzi SM, Potnik W, Mojon DS. Opinions of dating agents about strabismic subjects’ ability to find a partner. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:765–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.128884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goff MJ, Suhr AW, Ward JA, et al. Effect of adult strabismus on ratings of official U.S. Army photographs. J AAPOS. 2006;10:400–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mojon-Azzi SM, Kunz A, Mojon DS. Strabismus and discrimination in children: are children with strabismus invited to fewer birthday parties? Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:473–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2010.185793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mojon-Azzi SM, Mojon DS. Strabismus and employment: the opinion of headhunters. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87:784–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2008.01352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Multi-ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study Group. Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in African American and Hispanic children ages 6 to 72 months: the Multi-ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1229–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman DS, Repka MX, Katz J, et al. Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in white and African American children aged 6 through 71 months: the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2128–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atkinson J, Braddick O, Bobier B, et al. Two infant vision screening programmes: prediction and prevention of strabismus and amblyopia from photo- and videorefractive screening. Eye (Lond) 1996;10:189–98. doi: 10.1038/eye.1996.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg AE, Mohney BG, Diehl NN, Burke JP. Incidence and types of childhood esotropia: a population-based study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:170–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohney BG. Common forms of childhood esotropia. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:805–9. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00639-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raab EL. Etiologic factors in accomodative esodeviation. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1982;80:657–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Von Noorden GK, Campos EC. Binocular Vision and Ocular Motility: Theory and Management of Strabismus. 6. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2002. p. 548. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joint Writing Committee for the Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study and Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study Groups. Risk factors for hyperopia and myopia in preschool children: the Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study and the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.030. Accepted for publication on June 3, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varma R, Deneen J, Cotter S, et al. Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study Group. The Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study: design and methods. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2006;13:253–62. doi: 10.1080/09286580600719055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman DS, Repka MX, Katz J, et al. Prevalence of decreased visual acuity among preschool-aged children in an American urban population: the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study, methods, and results. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1786–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moke PS, Turpin AH, Beck RW, et al. Computerized method of visual acuity testing: adaptation of the Amblyopia Treatment Study visual acuity testing protocol. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:903–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmes JM, Beck RW, Repka MX, et al. Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. The Amblyopia Treatment Study visual acuity testing protocol. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1345–53. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.9.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cotter SA, Tarczy-Hornoch K, Wang Y, et al. Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study Group. Visual acuity testability in African-American and Hispanic children: the Multi-ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:663–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan Y, Tarczy-Hornoch K, Cotter SA, et al. Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study (MEPEDS) Group. Visual acuity norms in pre-school children: the Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86:607–12. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181a76e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cotter SA, Tarczy-Hornoch K, Song E, et al. Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study Group. Fixation preference and visual acuity testing in a population-based cohort of preschool children with amblyopia risk factors. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:145–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman DS, Katz J, Repka MX, et al. Lack of concordance between fixation preference and HOTV optotype visual acuity in preschool children: the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1796–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thibos LN, Wheeler WW, Horner D. Power vectors: an application of Fourier analysis to the description and statistical analysis of refractive error. Optom Vis Sci. 1997;74:367–75. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199706000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller JM. Clinical applications of power vectors. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86:599–602. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181a6a211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cleveland WS, Devlin SJ. Locally-weighted regression: an approach to regression analysis by local fitting. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83:596–610. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chew E, Remaley NA, Tamboli A, et al. Risk factors for esotropia and exotropia. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:1349–55. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090220099030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torp-Pedersen T, Boyd HA, Poulsen G, et al. In-utero exposure to smoking, alcohol, coffee, and tea and risk of strabismus. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:868–75. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hakim RB, Tielsch JM. Maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy: a risk factor for childhood strabismus. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:1459–62. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080220121033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ponsonby AL, Brown SA, Kearns LS, et al. The association between maternal smoking in pregnancy, other early life characteristics and childhood vision: the Twins Eye Study in Tasmania. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14:351–9. doi: 10.1080/01658100701486467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCarty C, Story I, Devereux C, et al. Prenatal factors in infantile strabismus. Aust Orthopt J. 2004–2005;38:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stone RA, Wilson LB, Ying GS, et al. Associations between childhood refraction and parental smoking. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4277–87. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joint Writing Committee for the Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study and Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study Groups. Risk factors for astigmatism in preschool children: the Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study and the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.033. Accepted for publication on June 3, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chapter: Smoking harms reproduction. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. [Accessed August 10, 2010]. Surgeon General’s Report: The Health Consequences of Smoking. Chapter #; pp. 17–19. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2004/pdfs/whatitmeanstoyou.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leonardi-Bee J, Smyth A, Britton J, Coleman T. Environmental tobacco smoke and fetal health: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2008;93:F351–61. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.133553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ernst M, Moolchan ET, Robinson ML. Behavioral and neural consequences of prenatal exposure to nicotine. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:630–41. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200106000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wigle DT, Arbuckle TE, Turner MC, et al. Epidemiologic evidence of relationships between reproductive and child health outcomes and environmental chemical contaminants. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2008;11:373–517. doi: 10.1080/10937400801921320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swanson JM, Entringer S, Buss C, Wadhwa PD. Developmental origins of health and disease: environmental exposures. Semin Reprod Med. 2009;27:391–402. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1237427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Chapter 5. Reproductive and Developmental Effects from Exposure to Secondhand Smoke. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2006. [Accessed June 12, 2011.]. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General; pp. 169–174. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/secondhandsmoke/report/fullreport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mendola P, Selevan SG, Gutter S, Rice D. Environmental factors associated with a spectrum of neurodevelopmental deficits. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2002;8:188–97. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colburn JD, Morrison DG, Estes RL, et al. Longitudinal follow-up of hypermetropic children identified during preschool vision screening. J AAPOS. 2010;14:211–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robaei D, Rose KA, Ojaimi E, et al. Causes and associations of amblyopia in a population-based sample of 6-year-old Australian children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:878–84. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.6.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ip JM, Robaei D, Kifley A, et al. Prevalence of hyperopia and associations with eye findings in 6- and 12-year-olds. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:678–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anker S, Atkinson J, Braddick O, et al. Identification of infants with significant refractive error and strabismus in a population screening program using noncycloplegic videorefraction and orthoptic examination. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:497–504. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ingram RM, Arnold PE, Dally S, Lucas J. Results of a randomised trial of treating abnormal hypermetropia from the age of 6 months. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990;74:158–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.74.3.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ingram RM, Walker C, Wilson JM, et al. Prediction of amblyopia and squint by means of refraction at age 1 year. Br J Ophthalmol. 1986;70:12–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.70.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Atkinson J, Anker S, Bobier W, et al. Normal emmetropization in infants with spectacle correction for hyperopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:3726–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Donahue SP, Arnold RW, Ruben JB AAPOS Vision Screening Committee. Preschool vision screening: what should we be detecting and how should we report it? Uniform guidelines for reporting results of preschool vision screening studies. J AAPOS. 2003;7:314–6. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(03)00182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spencer JB. A practical approach to refraction in children. Focal Points. 1993:4. [Google Scholar]

- 50.American Academy of Ophthalmology Pediatric Ophthalmology/Strabismus Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern. Pediatric Eye Evaluations. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2007. [Accessed August 15, 2010]. Esotropia and Exotropia PPP. Available at: http://one.aao.org/ce/practiceguidelines/ppp_content.aspx?cid=89921a42-f4b1-47e4-a5ef-6cbbce4d0197#introduction. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study Group. Prevalence of myopia and hyperopia in 6- to 72-month-old African American and Hispanic children: the Multi-ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:140–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giordano L, Friedman DS, Repka MX, et al. Prevalence of refractive error among preschool children in an urban population: the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:739–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huynh SC, Wang XY, Ip J, et al. Prevalence and associations of anisometropia and aniso-astigmatism in a population based sample of 6 year old children. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:597–601. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.083154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robaei D, Rose KA, Kifley A, et al. Factors associated with childhood strabismus: findings from a population-based study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1146–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Connor AR, Stephenson TJ, Johnson A, et al. Strabismus in children of birth weight less than 1701 g. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:767–73. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weakley DR, Jr, Birch E, Kip K. The role of anisometropia in the development of accommodative esotropia. J AAPOS. 2001;5:153–7. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2001.114662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weakley DR, Jr, Birch E. The role of anisometropia in the development of accommodative esotropia. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2000;98:71–6. discussion 76–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weakley DR., Jr The association between nonstrabismic anisometropia, amblyopia, and subnormal binocularity. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:163–71. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weakley DR. The association between anisometropia, amblyopia, and binocularity in the absence of strabismus. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1999;97:987–1021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pathai S, Cumberland PM, Rahi JS. Prevalence of and early-life influences on childhood strabismus: findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:250–7. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gallo JE, Lennerstrand G. A population-based study of ocular abnormalities in premature children aged 5 to 10 years. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;111:539–47. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73695-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robaei D, Kifley A, Gole GA, Mitchell P. The impact of modest prematurity on visual function at age 6 years: findings from a population-based study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:871–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.6.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.O’Connor AR, Stewart CE, Singh J, Fielder AR. Do infants of birth weight less than 1500 g require additional long term ophthalmic follow up? Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:451–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.083550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Holmstrom G, Rydberg A, Larsson E. Prevalence and development of strabismus in 10-year-old premature children: a population-based study. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2006;43:346–52. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20061101-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Williams C, Northstone K, Howard M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for common vision problems in children: Data from the ALSPAC study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:959–64. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.134700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Atkinson J, Braddick OJ, Durden K, et al. Screening for refractive errors in 6–9 month old infants by photorefraction. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68:105–12. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.2.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nusz KJ, Mohney BG, Diehl NN. Female predominance in intermittent exotropia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:546–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aurell E, Norrsell K. A longitudinal study of children with a family history of strabismus: factors determining the incidence of strabismus. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990;74:589–94. doi: 10.1136/bjo.74.10.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Abrahamsson M, Magnusson G, Sjostrand J. Inheritance of strabismus and the gain of using heredity to determine populations at risk of developing strabismus. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1999;77:653–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1999.770609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Birch EE, Fawcett SL, Morale SE, et al. Risk factors for accommodative esotropia among hypermetropic children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:526–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Podgor MJ, Remaley NA, Chew E. Associations between siblings for esotropia and exotropia. Arch Ophthamol. 1996;114:739–44. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100130731018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sanfilippo PG, Hewitt AW, Hammond CJ, Mackey DA. The heritability of ocular traits. Surv Ophthalmol. 2010;55:561–83. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, et al. The validity of self-reported smoking: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1086–93. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.7.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Locally weighted scatter plot smoothing (LOWESS) plot illustrating the independent relationship between magnitude of spherical equivalent (SE) anisometropia and the prevalence of esotropia in 6- to 72-month-old children in the Multi-Ethnic and the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Studies (MEPEDS and BPEDS), after controlling for other risk factors.

Locally weighted scatter plot smoothing (LOWESS) plot illustrating the independent relationship between magnitude of J0 anisometropia and the prevalence of exotropia in 6- to 72-month-old children in the Multi-Ethnic and the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Studies (MEPEDS and BPEDS), after controlling for other risk factors.