Abstract

Objective

We examined effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) on cognitive decline as a function of phase of pre-clinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Methods

Given recent findings that cognitive decline accelerates as clinical diagnosis is approached, we used rate of decline as a proxy for phase of pre-clinical Alzheimer’s disease. We fit growth mixture models of Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS) trajectories with data from 2,388 participants in the Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT), and included class-specific effects of naproxen and celecoxib.

Results

We identified 3 classes: “no-decline”, “slow-decline”, and “fast-decline”, and examined effects of celecoxib and naproxen on linear slope and rate of change by class. Inclusion of quadratic terms improved fit of the model (−2 log likelihood difference: 369.23; p<0.001), but resulted in reversal of effects over time. Over four years, participants in the slow-decline class on placebo typically lost 6.6 3MS points, while those on naproxen lost 3.1 points (p-value for difference: 0.19). Participants in the fast-decline class on placebo typically lost 11.2 points, but those on celecoxib first declined and then gained points (p-value for difference from placebo: 0.04), while those on naproxen showed a typical decline of 24.9 points (p-value for difference from placebo: <0.0001).

Conclusions

Our results appeared statistically robust, but provided some unexpected contrasts in effects of different treatments at different times. Naproxen may attenuate cognitive decline in slow decliners while accelerating decline in fast decliners. Celecoxib appeared to have similar effects at first but then to attenuate change in fast decliners.

Keywords: NSAIDs, Alzheimer, prevention, Dementia, growth mixture models

Introduction

The relationship between inflammation, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and Alzheimer disease (AD) is complex, as evidenced by conflicting findings on the effects of NSAIDs on AD and AD risk. Given the public health impact of AD (Wimo et al., 2006), and the widespread use of NSAIDs among the elderly (Sloane Report, 2006), it is important to determine under what circumstances these medications may be helpful or harmful. We will argue that the pre-clinical period of AD can be usefully divided into 3 phases, and that these phases can be characterized by the rate at which individuals are declining. Further, we will argue that the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of AD varies between these different pre-clinical phases. As such, the effects of NSAID exposure on cognitive decline would also be expected to vary by phase of pre-clinical AD.

Conflicting results from NSAID trials

Studies of the effects of NSAID exposure on AD and AD risk have yielded conflicting results. A number of observational studies suggest that NSAIDs are associated with reduced AD risk. A meta-analysis of 7 non-prospective studies of AD and lifetime NSAID use yielded a combined odds ratio of 0.51 (95% CI: 0.40,0.66), while 3 prospective studies yielded a combined relative risk of 0.42 (95% CI: 0.26,0.66) (Szekely et al., 2004). More recent studies, including the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) and a case-control analysis of 246,199 US veterans, also report reduced AD risk among NSAID users, though a 12-year cohort study of 1,019 older Catholic clergy found no association (Szekely, et al., 2008; Vlad, et al., 2008; Arvanitakis et al., 2008).

By contrast, randomized placebo-controlled trials (RCT) of diclofenac, nimesulide, and naproxen failed to show an effect (Scharf et al., 1999; Aisen et al., 2002; Aisen et al., 2003). One trial showed a positive effect of indomethacin, but a subsequent study failed to replicate that finding (Rogers et al., 1993; deJong et al., 2008). Three trials of COX-2 specific inhibitors and one of aspirin also showed no benefit (Aisen et al., 2003; Reines et al., 2004; Soininen et al., 2007; AD2000, 2008).

NSAID prevention trials in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and normals showed a potential increase in AD risk. A large RCT of rofecoxib MCI showed increased AD hazard (Thal et al., 2005). Previously in the Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT), we reported hazard ratio estimates of 1.99 (95% CI: 0.80,4.97) and 2.35 (95% CI: 0.95,5.77) for celecoxib and naproxen, respectively (ADAPT Research Group, 2007). After exclusion of seven AD cases adjudicated to have been present at the time of randomization, these hazard ratio estimates increased to 4.11 (95% CI: 1.30, 13.0) and 3.57 (95% CI: 1.09,11.7) (ADAPT Research Group, 2007). Subsequent analyses of cognitive outcomes demonstrated a significant difference in global summary score decline for naproxen (β = −0.05; 95% CI: −0.09, −0.01) as compared to placebo, and significant 3MS-E differences in decline for both celecoxib (β = −0.32; 95% CI: −0.62,−0.02) and naproxen (β = −0.36; 95% CI: −0.68,−0.04) as compared to placebo (ADAPT, 2008).

Phases of Pre-Clinical AD

AD develops over the course of decades, and the pre-clinical period can be usefully divided into three phases (Lyketsos et al., 2008) which can be characterized by rate of cognitive decline. These phases are distinct and separate from previously described stages of AD which follow clinical diagnosis. During the first phase, there is little or no cognitive decline. Supporting this period as a distinct phase are findings of stage A amyloid deposits and stage I/II neurofibrillary changes in the brains of individuals autopsied as young as 40, studies with 11C-PET-PiB confirming the presence of amyloid in the brains of non-impaired elderly, and MRI studies showing brain atrophy in cognitively normal subjects (Braak & Braak, 1997; Aizenstein et al., 2008; Fripp et al., 2008; Fennema-Notestine, 2009).

Several prospective studies of asymptomatic individuals with higher genetic risk have documented subtle memory declines which predicted conversion to MCI and correlated with cerebral glucose metabolism (Reiman et al., 1996; Caselli et al., 2008). Additional long-term prospective studies have demonstrated differences on cognitive tests in individuals who ultimately developed dementia as many as 9 years prior to diagnosis, and experiencing steeper declines 2–3 years prior to diagnosis (Small et al., 2000; Backman et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2001; Amieva et al., 2008; Small & Backman, 2007; Howieson et al., 2008). These findings support further division of the preclinical period into slow (phase 2) and fast (phase 3) periods of cognitive decline. We would expect that a sample of elderly individuals without clinical diagnoses of dementia would contain individuals in each of these three pre-clinical phases (as well as some who were not destined to develop dementia). If followed, their cognitive trajectories could then be classified as belonging to one of the 3 cognitive decline phases. Such an analysis has been done using growth mixture modeling (GMM) and data from the Cambridge City over 75 Cohort Study, and the authors reported findings in support of three classes of trajectories based on patterns of mini-mental state exam (MMSE) scores over 21 years: one class starting out unimpaired at baseline with a slow decline, a second starting out moderately impaired with sharper decline, and a third starting out moderately impaired but with an accelerating rate of decline (Terrera et al., 2009).

Changing Role of Inflammation during the Phases of Pre-Clinical AD

The pathogenesis and progression of AD is attended by a variety of inflammatory processes, but it is unclear whether these processes cause, are a byproduct of, or ameliorate the proliferation of amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and neuronal loss (Akiyama, et al., 2000; Wyss-Coray 2006). According to the amyloid cascade/neuroinflammation hypothesis, amyloid-beta (Aβ) activates microglial cells, which promote amyloid plaque formation (Akiyama, et al., 2000). This is supported by reports of Aβ secretion by cultured microglia, and evidence that microglia are involved in the laying down of amyloid fibrils (Bauer et al., 1991; Bitting et al., 1996; Wisniewski & Wegiel, 1994). In autopsy studies of normal elderly, microglia were associated with neuritic, but not diffuse plaques (Mackenzie et al., 1995, Sasaki et al., 1997). Interleukin-1 (IL-1) over-expression by activated microglia has also been shown to cause tau phosphorylation and tangle development (Mrak & Griffin, 2005). Hence, inflammation in the form of microglial activation promotes AD neuropathy in the early phase(s) of preclinical AD.

Inflammatory processes can also be neuroprotective. Microglia also participate in plaque phagocytosis (Shaffer et al., 1995; Paresce et al., 1997). The cytokine interleukin-3 (IL-3) has been shown to inhibit Aβ(1–42)-mediated neuronal death (Rojo, 2008), and compared to normal elderly controls, those with mild AD have lower secretion of IL-3 by mononuclear cells (Huberman et al., 1994). This suggest that inflammatory processes play a role in plaque and tangle formation, but some are also involved in plaque clearance and neuroprotection.

NSAID effects on Cognitive Decline vary by Timing of Exposure

We hypothesize that the role of inflammation changes during the course of pre-clinical AD, such that it is harmful during the early phases (1&2), when plaques and tangles are being formed, but that once substantial numbers of plaques have formed (phase 3), inflammation is helpful, and necessary for plaque clearance. Therefore, we would expect NSAID exposure during early phases to be protective, but harmful during the later phase. To date, there are no analyses stratifying individuals by pre-clinical phase. However, analyses stratified by age of NSAID exposure yield comparable results. In the Cardiovascular Health Study, reduced risk of AD in NSAID users was only significant in the younger group (Szekely et al., 2008). In the Cache County Study on Memory and Aging, individuals using NSAIDs before age 65 had shallower cognitive decline compared to non-users, while decline for those who began after 65 was steeper (Hayden et al., 2007). In the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) study, hazard ratios for current heavy users was higher than those of remote users, suggesting a gradient of risk with timing of exposure (Breitner et al., 2009a). Finally, in the ADAPT study, when the study interval was divided into pre-defined early and late periods, risk of incident AD was increased early on in both the celecoxib and naproxen treatment groups for 54 individuals who had mild cognitive impairment at enrollment, and who were likely in the third phase of pre-clinical AD (Breitner et al., 2009b).

If pre-clinical phase were an observed variable, (e.g., measureable by some biomarker) our hypothesis could be tested using phase-stratified analyses. Absent such a biomarker, we will use growth mixture models (GMM) to differentiate the pre-clinical phases as latent classes based on observed trajectories of cognitive decline. We will then test for latent class-specific effects of NSAID treatment. The objectives of these analyses are to 1) empirically confirm the existence of three classes of trajectories of cognitive decline (representing the three phases of pre-clinical AD) using longitudinal scores on the Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS), 2) determine if NSAID treatment differentially affects rate of decline by phase of pre-clinical AD, and 3) validate the model by replicating the number of classes of trajectories, as well as the differential NSAID effects by class, on a second measure, the Dementia Severity Rating Scale (DSRS).

Methods

Study Population and Design

ADAPT was a randomized, placebo-controlled, multisite primary prevention trial. Study methods have been previously reported in detail (ADAPT Research Group, 2007). Participants were recruited through mailings to Medicare beneficiaries near the study’s field sites (Baltimore, MD; Boston MA; Rochester, NY; Seattle, WA; Sun City, AZ; and Tampa, FL). Eligible participants were aged 70+ and had at least one first-degree relative with Alzheimer-like dementia. This study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (#NCT00007189) and approved by local institutional review boards. Informed consent was obtained from each participant along with an informant. The 2,528 participants received 200 mg of celecoxib bid, 220 mg of naproxen sodium bid, or matching placebo. Randomization was on a 1:1:1.5 basis, stratified by age and study site. At baseline and yearly, participants were evaluated with a cognitive assessment battery, including the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS) (Teng & Chui, 1987), and the Dementia Severity Rating Scale (DSRS) (Clark & Ewbanks, 1986). The 3MS is a widely-used, 100 point global cognitive measure with higher scores indicative of better cognitive functioning. For parity with other ADAPT analyses, we used education-adjusted 3MS scores in all analyses (Elkins et al., 2006; ADAPT, 2008). The DSRS is a multiple-choice questionnaire completed by a knowledgeable informant who rates impairment in 12 cognitive and functional domains. Scores range from 0 to 54; higher scores indicate greater impairment (Clark & Ewbanks, 1986). On December 17th, 2004, treatment was suspended due to safety concerns, but yearly cognitive testing continued until September 2007 (ADAPT, 2008). Analyses were conducted as “intent-to-treat”, such that individuals stayed in their treatment groups even after treatment was halted.

Analytic Methods

Growth mixture models (GMMs) allow for the grouping of individuals based on similarities among their trajectories on an outcome measured over time. They are based on an underlying assumption that each individuals’ scores over time are the result of their being a member of a latent (unobserved) class. For each latent class of trajectories, the average intercept, slope and quadratic term are estimated. For each individual, probabilities of membership in each class are calculated based on how well their trajectory matches the mean trajectories of each of the classes, and these probabilities can be used to assign individuals. GMMs also allow for the inclusion of treatment effects on the slope and quadratic terms of each trajectory class, and these are analogous to interactions between treatment and time or time squared in standard longitudinal regression models. These models also allow for the inclusion of variables which predict class membership. For more details on GMMs, please see Appendix I.

After determining the appropriate number of latent trajectory classes, we added treatment effects for both celecoxib and naproxen on the slope and quadratic terms. We compared a model in which the treatment effects on the trajectories were the same across all classes to a model in which they were allowed to be different using a likelihood ratio test. We then added age and APOE genotype as predictors of class membership. We then compared numbers of individuals randomized to each treatment and mean time on treatment across latent classes. Ideally, the fitted model would be replicated in an independent sample. Since it is unlikely that the ADAPT study will ever be replicated, instead, we replicated the class structure and treatment effects using an additional measure, the DSRS. Programming details and model output are available from the first author upon request.

Results

Demographics and other sample information are reported elsewhere; treatment groups did not differ significantly on any baseline variables (ADAPT, 2008). Growth mixture models were run using data from 2,388 individuals with complete covariate (age and APOE) information. Years on treatment did not differ by treatment assignment: Placebo: 1.79 (1.05); Celecoxib: 1.83 (1.02); Naproxen: 1.81 (1.05). Based on fit statistics, bootstrapped likelihood ratio tests, and estimability, we chose a 3-class model. Inclusion of the quadratic term improved fit (−2 log likelihood difference (−2LLD): 369.23; p<0.001). A model allowing different treatment effects on trajectories between classes fit the data significantly better than a model in which treatment effects were constant across classes (−2LLD: 369.23; p<0.001). The inclusion of APOE and age at baseline as predictors of class membership improved the fit further (−2LLD: 106.65, p<0.001). Age was a significant predictor of baseline 3MS score. Table 1. shows estimates from the final model. The majority of individuals (86%) were in the “no-decline” class with high baselines and minimal declines. A smaller group (10%) were in a “slow-decline” class with lower baselines and shallow declines. The remaining 4% were in a “fast-decline” class with the lowest baselines and sharp declines. The three classes did not differ significantly by proportion of individuals on celecoxib and naproxen (class 1: 0.29, 0.29; class 2: 0.29, 0.28; class 3: 0.29, 0.29) or by mean years of treatment prior to discontinuation (class 1: 1.82(1.09); class 2: 1.79(1.04); class 3: 1.58(1.14)). As expected, APOE was significantly associated with increased log odds of class membership in classes 2 and 3 relative to class 1. Higher age at baseline was significantly associated with membership in class 2.

Table 1.

3MS Growth Mixture Model Parameter Estimates

| Class 1 (no-decline) |

Class 2 (slow decline) |

Class 3 (fast decline) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | 0.86 | 0.10 | 0.04 | |

| Baseline 3MS score | 94.73 (0.08)1 | 91.7 (0.27) | 86.31 (0.28) | |

| Rate of decline2 | −0.32 (0.09)** | −0.84 (0.53) | 5.63 (0.81)** | |

| Change in rate of decline3 | 0.04 (0.02)* | −0.20 (0.07)* | −2.11 (0.11)** | |

| Effect of Age on Baseline 3MS Score | −0.13 (0.02)** | |||

| Log Odds of Class Membership | Age | 0.13 (0.03)** | 0.07 (0.04) | |

| APOE | 1.12 (0.23)** | 0.89(0.28)** | ||

| Effect of Celecoxib on | Rate of decline4 | −0.20 (0.13) | −0.88 (0.68) | −2.87 (1.64) |

| Change in rate of decline5 | 0.06 (0.03) | −0.02 (0.11) | 1.49 (0.25)** | |

| Effect of Naproxen on | Rate of decline | 0.05 (0.14) | −1.73 (0.75)* | −3.30 (0.97)** |

| Change in rate of decline | −0.02 (0.03) | 0.65 (0.10)** | −0.03 (0.19) | |

parameter estimate (standard error)

effect of time

effect of time2

interaction between treatment and time

interaction between treatment and time2

p<0.05,

p<0.01

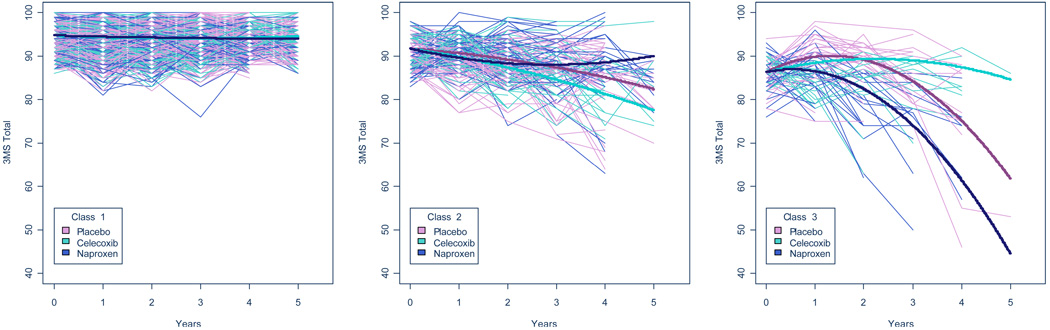

Table 2 shows expected 3MS score changes over the first four years for each class. In class 1 (no-decline), individuals in all three treatment groups were stable over 4 years. In class 2 (slow-decline), the expected declines for placebo, naproxen, and celecoxib were 6.6 points, 3.1 points, 10.5 points, respectively, but these differences were not statistically significant. In class 3 (fast-decline), individuals on placebo were expected to lose 11.2 points, individuals on naproxen were expected to lose 24.9 points, but those on celecoxib were expected to gain 1.1 points. Both treatments were statistically significantly different from placebo. Figure 1. shows fitted trajectories (bold lines) for each treatment group along with individual observed trajectories (thin lines) for all study participants.

Table 2.

Predicted 3MS Changes Over 4 Years by Latent Class and Treatment Group

| Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | −0.59 (−1.33,0.16)1 |  |

−6.62 (−10.62,−2.61) |  |

−11.23 (−15.55,−6.91) |  |

| Naproxen | −0.74 (−1.3,−0.19) | −3.14 (−7.44,1.17) | −24.9 (−28.49,−21.32) | |||

| Celecoxib | −0.52 (−1.01,−0.02) | −10.46 (−14.71,−6.21) | 1.12 (−10.6,12.83) |

Predicted change in 3MS score after 4 years for individuals in class 1 who were treated with placebo, (95% CI)

p-value for the within-class comparison of predicted 4 year change in 3MS score on naproxen versus placebo.

Figure 1. Predicted and Observed 3MS Trajectories by Latent Class and Treatment Group.

Each class is shown in a separate panel. Bold lines (one for each treatment group) denote predicted class-specific trajectories. Thin lines denote observed 3MS scores over time for each individual in the study, color-coded by treatment. For this figure, individuals were assigned to the class of which they were most like be a member.

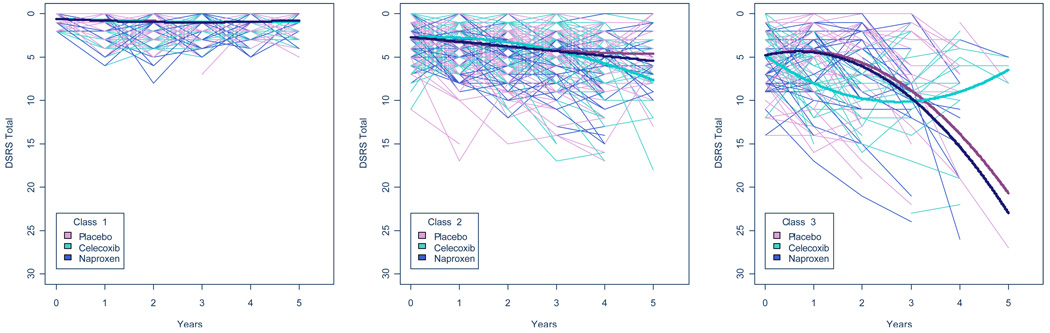

We followed a similar model-fitting process with our validating outcome, DSRS. As with the 3MS, we chose a 3-class model; a model with class-specific treatment effects fit better than a model with class-invariant treatment effects (−2LLD = 34.77, p<0.001). Both APOE and age were significantly associated with membership in classes 1 and 2 (−2LLD= 62.09, p<0.001). The direct effect of age on intercept was not statistically significant, but was retained in the model to facilitate comparisons between the 3MS and DSRS models. Table 3 shows expected DSRS score changes over the first four years for each class. Figure 2 is analogous to Figure 1, but in order to facilitate comparisons, the vertical axes have been reversed.

Table 3.

Predicted DSRS Changes Over 4 Years by Latent Class and Treatment Group

| Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | 0.36 (−0.19,0.91)1 |  |

1.81 (0.50,3.12) |  |

9.04 (5.64,12.44) |  |

| Naproxen | 0.32 (−0.57,1.21) | 2.2 (0.89,3.51) | 10.53 (6.98,14.08) | |||

| Celecoxib | 0.35 (−0.7,1.4) | 3.07 (2.02,4.12) | 4.19 (−0.09,8.47) |

Predicted change in DSRS score after 4 years for individuals in class 1 who were treated with placebo, (95% CI)

p-value for the within-class comparison of predicted 4 year change in DSRS score on naproxen versus placebo.

Figure 2. Fitted and Observed DSRS Trajectories by Latent Class and Treatment Group.

Each class is shown in a separate panel. Bold lines (one for each treatment group) denote predicted class-specific trajectories. Thin lines denote observed DSRS scores over time for each individual in the study, color-coded by treatment. For this figure, individuals were assigned to the class of which they were most like be a member. To facilitate comparison with Figure 1., the vertical axis for DSRS has been reversed.

The 3MS and DSRS classes and NSAID effects are comparable despite the differences in scale and scope of the two measurement instruments. For both measures, 3-class models were estimated, and the shapes of those trajectories (no-decline, slow-decline, and fast-decline) were similar. Looking at the 4-year expected changes in both models, celecoxib had no effect on the no-decline class, a deleterious (but not significant for the 3MS) effect on the slow-decline class, and a substantial and statistically significant ameliorative effect on the fast-decline class. The results for naproxen were less clear. In both models it had no effect on the no-decline class, but in the 3MS model it was associated with a shallower downward slope relative to placebo for the slow-decline class, whereas in the DSRS model it was associated with a steeper slope, though neither of these differences was statistically significant at 4 years. For the fast-decline class, naproxen was associated with worse outcome in both models, but this difference was only statistically significant in the 3MS model.

Discussion

Data from both the 3MS and DSRS supported a three-class model: no-decline, slow-decline, and fast-decline. We hypothesized that NSAID exposure would slow cognitive decline in the slow-decline group and speed cognitive decline in the fast-decline group, as compared to individuals on placebo. The results were not clear-cut: naproxen seemed to confirm this hypothesis in the 3MS model, but in the DSRS model, while naproxen appeared harmful for the fast-decline class, it did not differ from placebo in the slow-decline class. Celecoxib showed a completely different pattern than expected: with both outcomes it appeared harmful for individuals in the slow-decline class and helpful for individuals in the fast-decline class. In post-mortem studies of individuals at different stages of AD (both pre- and post-clinical), neuronal COX-2 expression peaks early in the preclinical period and then decrease, whereas COX-1 expressing microglia are rarer early on but increase rapidly immediately prior to diagnosis (Hoozemans, et al., 2008, Hoozemans et al., 2011). If these processes are adaptive rather than harmful, it would explain why COX-2 inhibition with celecoxib in the earlier (slow-decline) phase appeared harmful, and why COX-1 inhibition by the non-specific COX inhibitor naproxen appeared harmful for individuals in the later (fast-decline) phase. Recent reports have shown that some NSAIDS (including celecoxib, but not naproxen) lower Aβ-42 levels, independent of their anti-inflammatory properties. However, a combined analysis of observational studies comparing NSAIDs with and without this property found no difference, though they did not stratify by pre-clinical disease stage or age (Szekeley et al., 2008).

There are several strengths to our analyses. Limiting enrollment to individuals over 70 with a family history of AD likely enriched the sample for pre-clinical AD. As an RCT, the timing, amount, and type of NSAID exposure are known and the results are not subject to the biases inherent in observational studies. The inclusion of both treatments allowed for differentiation between a COX-2 specific inhibitor and a non-specific COX1/COX2 inhibitor. Further, the use of growth mixture models is a significant advance over previous analyses that did not allow for NSAID effects to vary by pre-clinical phase. Apart from this, our analyses differ from previous ADAPT reports because the entire period of observation up to 5 years is included.

Several potential weaknesses related to the trial’s design are noted. First, the results are not directly comparable to the bulk of findings from observational studies in which the most commonly used NSAIDs were aspirin and ibuprofen. Also, since treatment was halted due to safety concerns, and enrollment occurred on a rolling basis, individuals were exposed to treatment for varying portions of the total time of observation. Though time on treatment did not vary significantly by treatment or class membership, there was a clear trend for shorter time on treatment for members of class 3 (fast-decline). Since treatment comparisons were made within rather than across classes, this is likely to have biased the results toward the null hypothesis by effectively decreasing the sample size in that class. Another potential issue is the assumption that all individuals experiencing cognitive decline are on an AD trajectory. Although the majority (67/75) of dementia cases have been adjudicated as AD, it is likely that some of these cases also have a vascular component, along with many individuals who have not yet received a clinical diagnosis. Less is known about the trajectory of individuals with VaD, but it can be assumed that inclusion of individuals on a non-AD path would increase the “noise” within the sample, introduce uncertainty in class membership, and bias the results toward the null.

It is premature to make a clinical recommendation, but our findings point to several potential avenues of research. First, these results should be replicated in one or more existing large observational studies. Further observation of ADAPT participants will make it possible to model drug effects on AD-free survival as a function of latent trajectory class. While more clinical trials are unlikely in the near-term, further in vitro and animal research into the role of inflammation and NSAIDs on AD pathogenesis is warranted, specifically with regard to differentiating which inflammatory processes are adaptive and which are potentially harmful, and when during the pre-clinical period these processes occur. Even if this work does not directly result in a treatment, it will have provided a valuable window on the pathophysiology of AD.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants T32-AG026778, U01-AG15477, and P50-AG005146.

Appendix I. Growth Mixture Modeling

Longitudinal data from clinical trials are typically analyzed using either marginal or mixed effects regression models. Marginal models are appropriate in cases where one is interested in the population-averaged effects of treatment (Diggle, et al., 2002). By contrast, mixed effects models allow for the modeling of heterogeneity in both intercept and slope (Diggle, et al., 2002), thus acknowledging that individuals both start and end at different places, in terms of their outcome scores measured over time. Both of these approaches, though, carry the assumption that all individuals originate from the same population. In some cases, it is reasonable to hypothesize that a sample is comprised of individuals from more than one population. Acknowledging this is particularly important if treatment effects vary by population. In an extreme case, if a treatment were helpful in one group, but harmful in the other, analyses which ignored group membership would suggest (erroneously) that the treatment had no effect on longitudinal course. When group membership is known, separate analyses by group is a simple solution. However, when group membership is unknown, or latent, then group/class membership can be modeled using a mixture, or latent class model. In fitting these models, it is assumed that each individual is a member of one and only one class, and that while class membership is unobserved, it can be inferred based on individuals’ observed data. Standard latent class analysis is based on patterns of responses on categorical, typically dichotomous, observed variables. Recently, a longitudinal extension has been developed which groups individuals based on the shapes of their longitudinal trajectories (Muthen & Asparouhov, 2009). These growth mixture models (GMMs) have been increasingly used to model heterogeneity in development (Muthen et al., 2002; Greenbaum et al., 2005; Kreuter & Muthen, 2008), and to model class-specific treatment effects (Muthen & Brown, 2009). Adaptation for use in dementia research is a natural extension (Terrera et al., 2009).

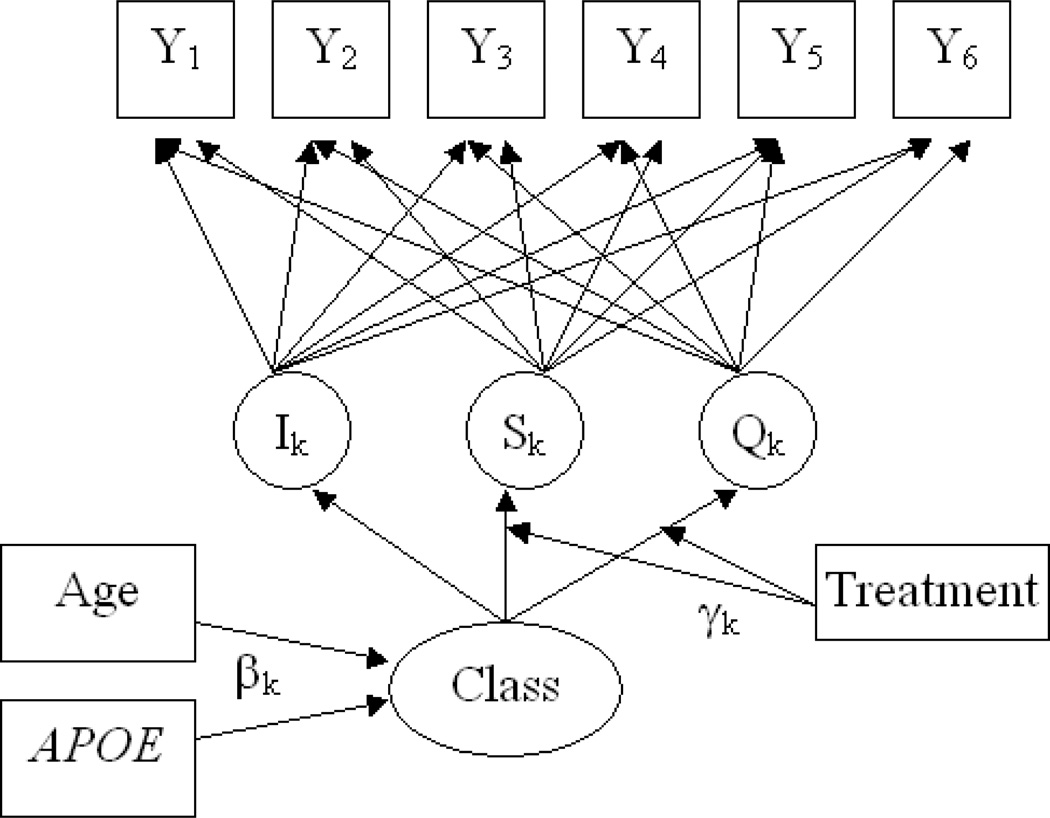

The simplest possible growth mixture model has a single class. Letting yij represent the outcome measure for the ith person at the jth timepoint aj, trajectory can be modeled as yij = I + Saj + Qaj + εij, where I, S, and Q represent the fitted intercept, slope, and quadratic term, respectively. As written, this is a marginal, or population-averaged model, because intercept, slope, and quadratic terms are the same for all individuals. If instead we wanted to allow these terms to vary by individual, we would write it as. Specifically, we want to allow these terms to vary as a function of class membership (indexed by k). We therefore write Ii = αI,k + ζI,i, Si = αS,k + ζS,i and Qi = αQ.k + ζQ,i where αI,k, αS,k, and, αQ,k are class-specific intercept, slope, and quadratic terms, respectively.

Now we wish to add treatment effects, with treatment as a dichotomous variable T. With a simple marginal model, we could add two interaction terms: The interpretation of the interaction terms γs and γQ are then the differences in slopes and quadratic terms, respectively, between those treated and untreated. To allow these terms to vary by class, we now include these interactions into the equations for S and Q, and write Si = αS,k + γS,kT + ζS,i and Qi = αQ.k + γQ,kT + ζQ,i.

With growth mixture models, it is also possible to model predictors of class membership. These variables are different from the longtudinal outcomes because they are conceptualized as causes, rather than effects, of latent class membership. Specifically, one models log odds of membership in a specific latent class, relative to a reference class. Typically the largest class, or the one containing the most “normal” individuals, is chosen as the reference class.

The fitting of GMMs entails the estimation of a large number of parameters and assumptions regarding the variances of the intercept, slope, and quadratic terms for each class. Additionally, the number of classes that are estimated affects substantially the parameter estimates and their interpretation. Therefore, GMM models should be built in a careful and sequential manner. Jung and Wickrama (2006) provide an excellent and accessible guide to this process. First, the number of classes of trajectories to estimate should be decided by fitting simplified (e.g., without drug effects or predictors of class membership) models with numbers of classes ranging from 1−5, and examining Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) statistics, bootstrap likelihood ratio tests (BLRT), graphical model fit, and parameter estimates (Nylund et al., 2007). If there is evidence of curvature in the trajectories, or an a priori hypothesis that such curvature will be present, then this process should be repeated with models which include quadratic terms. Models with and without quadratic terms can then be compared via likelihood ratio tests. If the p-value for the likelihood ratio test is less than 0.05, it can be taken as evidence that the model with fewer parameters (in this case, the model without the quadratic term) fits the data less well than the model with more parameters.

After determining an appropriate model for the observed outcome variables (Ys), treatment effects can then be added. To determine if drug effects vary by latent class, one can compare, again via likelihood ratio test, two models: one in which the treatment effects are constant across all of the classes, and one in which the treatment effects vary between classes. As a last step, predictors of class membership are added to the model. Figure 3. shows a schematic of the model estimated in this paper.

Figure 3. Schematic of Growth Mixture Model.

In some cases, there is a need to make additional comparisons among the latent classes. One approach is to assign individuals to the class of which they are mostly likely to be a member, and then stratify the analyses. However, this approach introduces bias in that it treats class membership as if it had been directly observed. A better approach is to multiply impute class membership and then to combine the results across the imputations, producing calculating a standard error estimate which takes into account the variability across the imputations (Bandeen-Roche, et al, 1997; Leoutsakos, et al., 2009).

ADAPT Research Group

Resource Centers. Chairman’s Office, Veteran Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System: John Breitner, MD (chairman); Jane Anau (coordinator); Janette Negele (previous coordinator); Melisa Montero (previous coordinator); Elizabeth Aigbe, MS; Jill Dorje; and Brenna Cholerton, PhD. Coordinating Center, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: Curtis Meinert, PhD (director); Barbara Martin, PhD (deputy director); Bonnie Piantadosi (coordinator); Robert Casper, MS; Michele Donithan, MHS; Hsu-Tai Liu, MD, MPH; Steven Piantadosi, MD PhD; Anne V. Shanklin, MA, CCRP; and Paul Smith.

Project Office, National Institute on Aging: Neil Buckholtz, MD (project officer); Laurie Ryan, MD (project officer); and Susan Molchan, MD.

Field Sites. Johns Hopkins School of Medicine: Constantine G. Lyketsos, MD, MHS (director); Martin Steinberg, MD (associate director); Jason Brandt, PhD (neuropsychologist); Julia J. Pedroso, RN, MA (coordinator); Alyssa Bergey; Themos Dassopoulos,MD; Melanie Dieter, MA; Carol Gogel, RN; Chiadi Onyike, MD; Lynn Smith; Veronica Wilson-Sturdivant; and Nadine Yoritomo, RN.

Boston University School of Medicine: Robert Green, MD (director); Sanford Auerbach, MD (associate director); Robert Stern, PhD (neuropsychologist); Patricia Boyle, PhD (previous neuropsychologist); Dawn Cisewski, PhD (previous neuropsychologist); Jane Mwicigi, MD, MPH (coordinator); Mary- Tara Roth, RN, MSN, MPH (previous coordinator); Lorraine Baldwin; Margaret Brickley, MS, RN, NP; Patrick Compton, RN; Debra Hanna, RN, BC, MPH; Sylvia Lambrechts; Janet Nafissi, MSN, APRN, BC; Andreja Packard, MD, PhD; and Mayuri Thakuria, MD, MPH.

University of Rochester School of Medicine: Saleem Ismail, MD(director); Pierre Tariot, MD (previous director); Anton Porsteinsson, MD (associate director); J. Michael Ryan,MD (previous associate director); Robin Henderson-Logan, PhD, ABPP-cn (neuropsychologist); Connie Brand, RN (coordinator); Colleen McCallum, MSW (previous coordinator); Suzanne Decker; Laura Jakimovick, RN, MS; Kara Jones, RN; Arlene Pustalka, RN; Jennifer Richard; Susan Salem-Spencer, RN, MS; and Asa Widman.

Veteran Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System and University of Washington School of Medicine: Suzanne Craft, PhD (director); Mark Fishel, MD (associate director); Laura Baker, PhD (neuropsychologist); Deborah Dahl, RN (coordinator); Kathleen Nelson, RN (previous coordinator); Susan Bigda, RN; Yoshie Biro; Ruth Boucher, RN; Nickolas Dasher; Edward DeVita, MD; Grace Garrett; Austin Hamm; Jeff Lindsey; and Laura Sissons-Ross.

Banner Sun Health Research Institute: Marwan Sabbagh, MD, FAAN (director); Joseph Rogers, PhD (associate director); Donald Connor, PhD, PhD (neuropsychologist); Carolyn Liebsack, RN, BSN, CCRC (coordinator); Nancy Thompson, RN (previous coordinator); Joanne Ciemo, MD; Kathryn Davis; Theresa Hicksenhiser, LPN; Sherry Johnson-Traver; Healther Kolody; Lisa Royer, RN; Nina Silverberg, PhD; and Deborah Tweedy, RN, MSN, CNP.

The Roskamp Institute Memory Clinic: Michael Mullan, MD, PhD (director); Cheryl Luis, PhD (associate director, neuropsychologist); Timothy Crowell, PsyD (previous associate director, neuropsychologist); Julia Parrish, LPN (coordinator); Laila Abdullah (previous coordinator); Theavy Chea; Scott Creamer; Melody Brooks Jayne, MD; Antoinette Oliver, MA; Summer Price, MA; and Joseph Zolton, ERT.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Excerpts of an earlier version of this manuscript were presented during the poster session and Junior Investigator awardee presentation at the 10th Annual Meeting of the International College of Geriatric Psychoneuropharmacology in Athens, Greece on September 15, 2010.

Conflicts of Interest:

Dr. Leoutsakos has no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Muthen is a developer and owner of MPLUS, the software used for the analyses in this paper.

Dr. Breitner previously held partial royalty interests in 2 United States patents for the use of NSAIDs for the prevention of AD; in January 2005 he assigned these interests irrevocably as a gift to a private charitable foundation in which he has no constructive or beneficial interest.

Dr. Lyketsos is a consultant to GlaxoSmithKline and receives lecture honoraria and support for continuing medical education activities from AstraZeneca, Eisai, Forest Laboratories, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, and Pfizer.

Pfizer provided celecoxib and matching placebo and Bayer Healthcare provided naproxen sodium and matching placebo for the ADAPT trial.

References

- AD2000 Collaborative Group. Bentham P, Gray R, Sellwood E, Hills R, Crome P, Raftery J. Aspirin in Alzheimer's disease (AD2000): a randomised open-label trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(1):41–49. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ADAPT Research Group. Lyketsos CG, Breitner JC, et al. Naproxen and celecoxib do not prevent AD in early results from a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2007;68(21):1800–1808. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260269.93245.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ADAPT Research Group. Cognitive function over time in the Alzheimer’s disease anti-inflammatory prevention trial (ADAPT): Results of a randomized, controlled trial of naproxen and celecoxib. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(7):896–905. doi: 10.1001/archneur.2008.65.7.nct70006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ADAPT Research Group. Alzheimer’s disease anti-inflammatory prevention trial: design, methods, and baseline results. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2009;5(2):93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aisen PS, Schmeidler J, Pasinetti GM. Randomized pilot study of nimesulide treatment in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 2002;58(7):1050–1054. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.7.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aisen PS, Schafer KA, Grundman M, et al. Effects of rofecoxib or naproxen vs placebo on Alzheimer disease progression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289(21):2819–2826. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.21.2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizenstein HJ, Nebes RD, Saxton JA, et al. Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(11):1509–1517. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H, Barger S, Barnum S, et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21(3):383–421. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amieva H, Le Goff M, Millet X, et al. Prodromal Alzheimer's disease: successive emergence of the clinical symptoms. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(5):492–498. doi: 10.1002/ana.21509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitakis Z, Grodstein F, Bienias JL, et al. Relation of NSAIDs to incident AD, change in cognitive function, and AD pathology. Neurology. 2008;70(23):2219–2225. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000313813.48505.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckman L, Jones S, Berger AK, Laukka EJ, Small BJ. Cognitive impairment in preclinical Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychology. 2005;19(4):520–531. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandeen-Roche K, Miglioretti DL, Zeger SL, Rathouz PJ. Latent variable regression for multiple discrete outcomes. J. Amer.Statistical Assoc. 1997;92(440):1375–1386. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer J, Konig G, Strauss S, et al. In-vitro matured human microphages express Alzheimer’s beta A4-amyloid precursor protein indicating synthesis microglial cells. FEBS Lett. 1991;282(2):335–340. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80508-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitting L, Naidu A, Cordell B, Murphy GM., Jr Beta-amyloid peptide secretion by a microglial cell line is induced by beta amyloid-(25–35) and lipopolysaccharide. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(27):16084–16089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Frequency of stages of alzheimer-related lesions in different age categories. Neurobiology of Aging. 1997;18(4):351–357. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitner JCS, Haneuse SJPA, Walker R, et al. Risk of dementia and AD with prior exposure to NSAIDs in an elderly community-based cohort. Neurology. 2009a;72:1899–1905. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a18691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitner JCS. Treatment effects of NSAIDS related to stage of Alzheimer’s pathogenesis: Lessons from ADAPT. Alzheimers Dement. 2009b;5(4) supp:144. [Google Scholar]

- Casellie RJ, Chen K, Lee W, Alexander GE, Reiman EM. Correlating cerebral hypometablolism with future memory decline in subsequent converters to amnestic pre-mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(9):1231–1236. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Ratcliff G, Belle SH, Cauley JA, DeKosky ST, Ganguli M, et al. Patterns of cognitive decline in presymptomatic Alzheimer disease: a prospective community study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(9):853–858. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CM, Ewbank DC. Performance of the dementia severity rating scale: A caregiver questionnaire for rating severity in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1986;10:31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong D, Jansen R, Hoefnagels W, et al. No effect of one-year treatment with indomethacin on Alzheimer's disease progression: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(1):e1475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. 2nd ed. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins JS, Longstreth WT, Jr, Manolio TA, et al. Education and the cognitive decline associated with MRI-defined brain infarct. Neurology. 2006;67(3):435–440. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228246.89109.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennema-Notestine C, McEvoy L, Hagler DJ, et al. Structural neuroimaging in the detection and prognosis of pre-clinical and early AD. Behavioral Neurology. 2009;21:3–12. doi: 10.3233/BEN-2009-0230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fripp J, Bourgeat P, Acosta O, et al. Appearance modeling of 11C PiB PET images: characterizing amyloid deposition in Alzheimer's disease, mild cognitive impairment and healthy aging. Neuroimage. 2008;43(3):430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum PE, Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Wang CP, Goldman MS. Variation in the drinking trajectories of freshmen college students. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(2):229–238. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden KM, Zandi PP, Khachaturian AS, et al. Does NSAID use modify cognitive trajectories in the elderly? The Cache County study. Neurology. 2007;69(3):275–282. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000265223.25679.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoozemans JJM, Rozemuller JM, van Hastert ES, Veerhuis R, Eikelenboom P. Cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 in the different stages of alzheimer’s disease pathology. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2008;14:1419–1427. doi: 10.2174/138161208784480171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoozemans JJM, Veerhuis R, Rozemuller JM, Eikelenboom P. Soothing the inflamed brain: Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on Alzheimer’s disease pathology. CNS Neurol Disord-DR. 2011;10(1):57–67. doi: 10.2174/187152711794488665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howieson DB, Carlson NE, Moore MM, et al. Trajectory of mild cognitive impairment onset. JINS. 2008;14(2):192–198. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708080375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huberman M, Shalit F, Ruth-Deri I, et al. Correlation of cytokine secretion by mononuclear cells of Alzheimer patients and their disease stage. J Neurommunol. 1994;52(2):147–152. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- in 't Veld BA, Launer LJ, Hoes AW, et al. NSAIDs and incident Alzheimer's disease. The Rotterdam Study. Neurobiol Aging. 1998;19(6):607–611. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(98)00096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung T, Wickrama KAS. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2:302–317. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter F, Muthen B. Analyzing criminal trajectory profiles: Bridging multilevel and group-based approaches using growth mixture modeling. J Quant Criminol. 2008;24:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Leotsakos JM, Zandi PP, Bandeen-Roche K, Lyketsos CG. Searching for valid psychiatric phenotypes: Discrete latent variable models. In J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010;19(2):63–73. doi: 10.1002/mpr.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, Szekely CA, Mielke MM, Rosenberg PB, Zandi PP. Developing new treatments for Alzheimer's disease: The who, what, when, and how of biomarker-guided therapies. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(5):871–889. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208007382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie IR, Hao C, Munoz DG. Role of microglia in senile plaque formation. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16(5):797–804. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)00092-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrak RZ, Griffin WS. Glia and their cytokines in progression of neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(3):349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B, Muthen L. Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B, Brown HB, Masyn K, et al. General growth mixture modeling for randomized preventive trials. Biostatistics. 2002;3(4):459–475. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/3.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Asparouhov T. Growth mixture modeling: Analysis with non-Gaussian random effects. In: Fitzmaurice G, Davidian M, Verbeke G, Molenberghs G, editors. Longitudinal Data Analysis. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press; 2009. pp. 143–165. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Brown H. Estimating drug effects in the presence of placebo response: Causal inference using growth mixture modeling. Statistics in Medicine. 2009;28:3363–3385. doi: 10.1002/sim.3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthen BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A monte carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling. 2007;14(4):535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Paresce DM, Chung H, Maxfield FR. Slow degradation of aggregates of the Alzheimer's disease amyloid beta-protein by microglial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(46):29390–29397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.29390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterns of medication use in the United States 2006: a report from the Slone Survey. [Accessed February 6, 2009]; http://www.bu.edu/slone/SloneSurvey/AnnualRpt/SloneSurveyWebReport2006.pdf.

- Reiman EM, Caselli RJ, Yun LS, et al. Preclinical evidence of Alzheimer’s disease in persons homozygous for the epsilon 4 allele for apolipoprotein E. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(12):752–758. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603213341202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reines SA, Block GA, Morris JC, et al. Rofecoxib: no effect on Alzheimer's disease in a 1-year, randomized, blinded, controlled study. Neurology. 2004;62(1):66–71. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J, Kirby LC, Hempelman SR, et al. Clinical trial of indomethacin in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1993;43(8):1609–1611. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.8.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojo LE, Fernandez JA, Maccioni AA, Jimenez JM, Maccioni RB. Neuroinflammation: implication for the pathogenesis and molecular diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Med Res. 2008;39(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A, Yamaguchi H, Ogawa A, Sugihara S, Nakuzato Y. Microglial activation in early stages of amyloid beta protein deposition. Acta Neropathol. 1997;94(4):316–322. doi: 10.1007/s004010050713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer LM, Dority MD, Gupta-Bansal R, et al. Amyloid beta protein (A beta) removal by neuroglial cells in culture. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16(5):737–745. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)00055-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf S, Mander A, Ugoni A, Vajda F, Christophidis N. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of diclofenac/misoprostol in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1999;53(1):197–201. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small BJ, Fratiglioni L, Viitanen M, Winblad B, Bäckman L. The course of cognitive impairment in preclinical Alzheimer disease: Three- and 6-year follow-up of a population-based sample. Arch Neurol. 2000;57(6):839–844. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.6.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small BJ, Backman L. Longitudinal trajectories of cognitive change in preclinical alzheimer’s disease: a growth mixture modeling analysis. Cortex. 2007;43:826–834. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70682-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soininen H, West C, Robbins J, Niculescu L. Long-term efficacy and safety of celecoxib in Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;23(1):8–21. doi: 10.1159/000096588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekely CA, Thorne JE, Zandi PP, Ek M, Messias E, Breitner JC, Goodman SN. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the prevention of Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review. Neuroepidemiology. 2004;23(4):159–169. doi: 10.1159/000078501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekely CA, Breitner JC, Fitzpatrick AL, et al. NSAID use and dementia risk in the Cardiovascular Health Study: role of APOE and NSAID type. Neurology. 2008;70(1):17–24. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000284596.95156.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekely CA, Green RC, Breitner JC, et al. No advantage of A beta 42-lowering NSAIDs for prevention of Alzheimer dementia in six pooled cohort studies. Neurology. 2008;70(24):2291–2298. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000313933.17796.f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48(8):314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrera GM, Brayne C, Matthews F CC75C Study Collaboration Group. One size fits all? Why we need more sophisticated analytical methods in the explanation of trajectories of cognition in older age and their potential risk factors. International Psychogeriatrics. 2009;22(2):291–299. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thal LJ, Ferris SH, Kirby L, et al. A randomized, double-blind, study of rofecoxib in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30(6):1204–1215. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlad SC, Miller DR, Kowall NW, Felson DT. Protective effects of NSAIDs on the development of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2008;70(19):1672–1677. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000311269.57716.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimo A, Jonsson L, Winblad B. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and direct costs of dementia in 2003. Dementia Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;21(3):175–181. doi: 10.1159/000090733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski HM, Wegiel J. The role of microglia in amyloid fibril formation. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1994;20(2):192–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T. Inflammation in Alzheimer disease: driving force, bystander, or beneficial response? Nat Med. 2006;12(9):1005–1015. doi: 10.1038/nm1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]