Abstract

Isoflurane exposure can protect the mammalian brain from subsequent insults like ischemic stroke. However, this protective preconditioning effect is sexually dimorphic, with isoflurane preconditioning decreasing male while exacerbating female brain damage in a mouse model of cerebral ischemia. Emerging evidence suggests that innate cell sex is an important factor in cell death, with brain cells having sex-specific sensitivities to different insults. We used an in vitro model of isoflurane preconditioning and ischemia to test the hypothesis that isoflurane preconditioning protects male astrocytes while having no effect or even a deleterious effect in female astrocytes following subsequent oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD). Sex-segregated astrocyte cultures derived from postnatal day 0 to 1 mice were allowed to reach confluency before being exposed to either 0% (sham preconditioning) or 3% isoflurane preconditioning for 2 hours. Cultures were then returned to normal growth conditions for 22 hours before undergoing 10 hours of OGD. Twenty-four hours following OGD, cell viability was quantified using a lactate dehydrogenase assay. Isoflurane preconditioning increased cell survival following OGD compared to sham preconditioning independent of innate cell sex. More studies are needed to determine how cell type and cell sex may impact on anesthetic preconditioning and subsequent ischemic outcomes in the brain.

Keywords: isoflurane, preconditioning, astrocyte, sex differences

Introduction

Exposing the brain to volatile anesthetics like isoflurane can induce tolerance, or “precondition” the brain from subsequent injurious insults such as ischemic stroke 1, 2. Protection from isoflurane preconditioning and subsequent ischemia has been shown to be male-specific, with female mice showing exacerbated injury following an identical treatment paradigm 3. This sexually dimorphic response to isoflurane preconditioning is partially mediated by circulating sex steroids 4, 5; however, it remains possible that innate cell sex in the brain is an additional contributing factor. Indeed, innate cell sex is emerging as an important factor in brain cell death, with neurons and astrocytes exhibiting sex-specific cell death mechanisms and outcomes following exposure to a variety of noxious insults 6–8, including oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD), an in vitro model of ischemia 9, 10.

Moreover, most reports investigating anesthetic preconditioning at the cellular level in the brain have been limited to mixed-sex primary neuronal cultures 11–15, leaving the role of astrocytes unexplored. Astrocytes comprise the majority of brain cells in mammals and are crucial in central nervous system function 16, 17. They also have roles facilitating the neurodegeneration that results from insults like ischemic stroke 17–19. Furthermore, astrocytes have been shown to respond to anesthetics, including isoflurane, by modifying glutamate uptake 20 and gap junction permeability 21. However, it remains unknown if preconditioning by a volatile anesthetic can affect astrocyte cell death outcomes following OGD, and if male and female astrocytes respond differently. In the current investigation, we used an in vitro model of isoflurane preconditioning and ischemia in astrocytes to test the hypothesis that isoflurane preconditioning protects male astrocytes while having no effect or even a deleterious effect in female astrocytes following subsequent OGD.

Material and Methods

Establishing sex-segregated cortical astrocyte cultures

Animal procedures were conducted in compliance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of animals in research, and experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

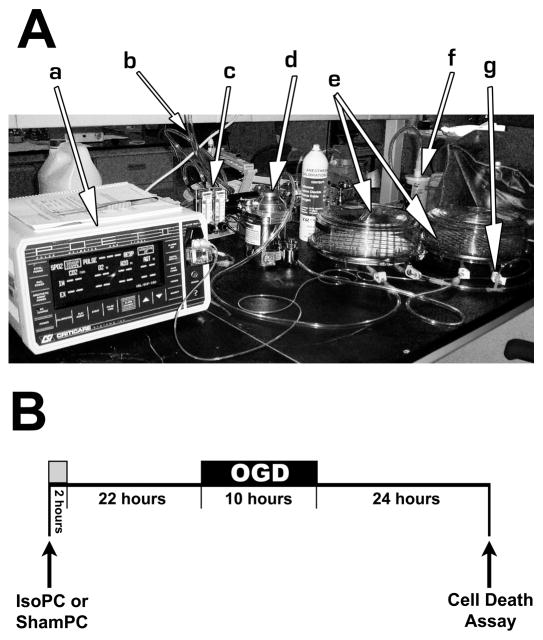

Sex-segregated astrocyte cultures were established and maintained as previously described 10 with the addition of a rinsing step to help remove non-adherent cells (described below). Male and female C57BL/6 (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) mouse pups (postnatal day 0 to 1) were segregated by sex based upon a larger genital papilla and longer ano-genital distance in males versus females. To confirm the sex-segregation technique for the experiments conducted here, tail tissue from randomly-selected male and female postnatal mouse pups was collected for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. Genomic DNA was extracted and prepared for PCR analysis using the DNeasy kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands). Two PCR reactions were conducted contemporaneously using the male-specific Y chromosome gene, Sry, to identify male animals and the gene for myogenin (Myog) as an autosomal control in both males and females 22. Validation of sex assignment was confirmed using the following primers: Sry, 5′–TCATGAGACTGCCAACCACAG–3′ and 5′–CATGACCACCACCACCACCAA–3′; Myog, 5′–TTACGTCCATCGTGGACAGC–3′ and 5′–TGGGCTGGGTGTTAGTCTTA–3′. The expected sizes of the PCR products are 441 base pairs for Sry (male) and 245 base pairs for Myog (males and females). The PCR reactions were carried out with one 72 °C period for 2 minutes, 30 cycles (94 °C for 5 sec, 65 °C for 30 sec, 72 °C for 30 sec), and one 72 °C period for 7 minutes. Figure 1 shows representative PCR products from six randomly-selected male and female pups. Additional PCR rounds from other litters were conducted with 100% accuracy for male and female segregation.

Figure 1.

Representative PCR products verifying sex segregation of postnatal day 0 to 1 mouse pups. Tail tissue from 6 randomly-selected female and male pups was digested and assayed for the presence of the male-specific Y chromosome gene, Sry, and the autosomal gene, myogenin (Myog), as a positive control. Primers without DNA, and DNA without primers, were used as negative control reactions. The asterisks indicate the 500 bp marker. The expected Sry and Myog products are at 441 and 245 bps, respectively.

Using the techniques described above, male and female pups from the same litter were segregated by sex and the brains from each sex were pooled to establish male or female cortical astrocyte cultures. These littermate cultures followed an identical, concurrent paradigm throughout the course of subsequent treatments to represent a given n = 1, where the sex-dependent and preconditioning-dependent paired analysis compared means from the same litter (see Statistics). Cortices were dissected in an ice-cold Hanks Balanced Salt Solution buffer followed by dissociation in 0.125% trypsin for 10 min at 37 °C. The trypsin reaction was stopped with the addition of 0.04 mg/ml of soybean trypsin inhibitor and 0.04 mg/ml of DNase was added to prevent clumping. The cells were washed twice in growth media (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium without phenol red), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, and 100 units of penicillin and streptomycin to reduce the probability of bacterial contamination. Cells were then plated at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells/cm2. The cells were allowed to settle overnight before being gently swirled and rinsed with fresh media to remove non-adherent, spherical, phase bright cells that settled on top of the astrocyte cell layer, thereby contributing to a more morphologically homogenous astrocyte culture. Cultures consisted of approximately 90–98% astrocytes as determined by immunostaining with antibodies specific for the astrocyte marker glial fibrillary acidic protein and with the nuclear stain 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole to label all cells (data not shown).

Male and female cells from the same litter were plated into separate rows across each of 3 different culture plates (24-well plates, 4 to 6 well replicates per row) with one row having male cells and another row having littermate female cells. Each experiment required 3 culture plates subjected to isoflurane preconditioning without OGD, sham preconditioning + OGD, and isoflurane preconditioning + OGD. The astrocytes were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2 until confluent, usually 10 to 14 days in vitro.

Cell culture reagents, including Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium, fetal bovine serum, trypsin, soybean trypsin inhibitor, glutamine, and streptomycin and penicillin are from Life Technologies (Invitrogen), Carlsbad, CA.

In vitro isoflurane preconditioning of astrocytes

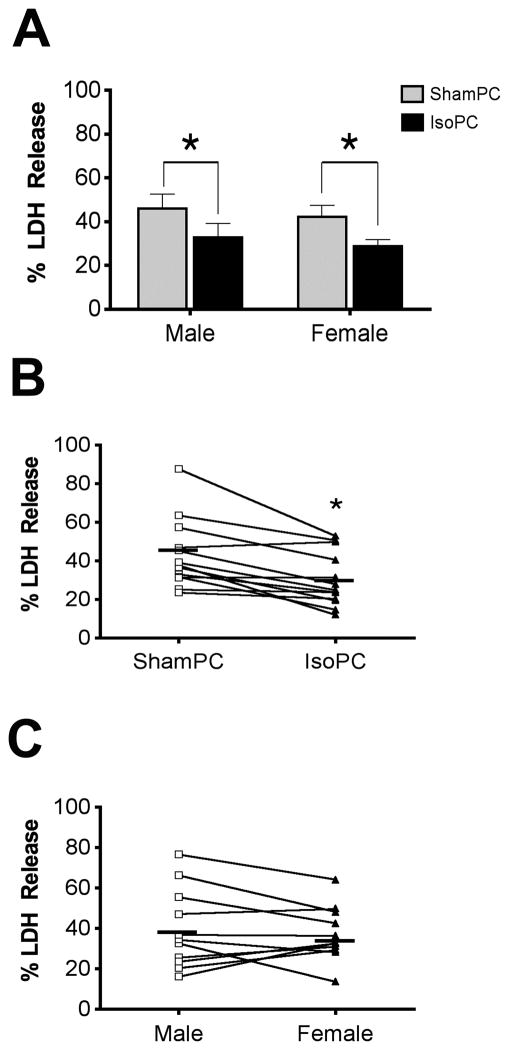

Instead of dissolving liquid isoflurane into solution, which can result in highly variable anesthetic concentrations through rapid evaporation 23, 24, we modified previously reported designs for exposing cultured cells to a volatile anesthetic for application to astrocytes15, 20, 25. Two air-tight, plastic chambers (Billups-Rothenberg, Del Mar, CA) were filled with medical air and 5% CO2, with or without 3% isoflurane (Figure 2A). For isoflurane preconditioning, astrocytes were exposed to 3% isoflurane in one chamber, while sham preconditioned astrocytes were exposed to 0% isoflurane in the other chamber. An anesthetic monitor (POET II, Criticare Systems, Waukesha, WI) was attached to the outflow of the isoflurane preconditioning chamber to determine when the isoflurane concentration had reached 3% in the chamber. While we did not measure the amount of isoflurane dissolved in the culture media, a 3% gas volume is within the range commonly used for in vitro volatile anesthetic studies 14, 20, 25–28 and has been shown to translate to clinically-relevant concentrations (upper micromolar to lower millimolar) 12, 29. The inflow and outflow ducts were then clamped and each chamber was placed in a standard 37 °C incubator during the 2 hour preconditioning period. Following the 2 hour preconditioning period, the culture plates were removed from the chambers and returned to normal growth conditions for 22 hours before OGD. The treatment paradigm is illustrated in Figure 2B. The 3% isoflurane concentration, 2 hour preconditioning period, and 24 hour post-preconditioning period were chosen based upon similar models demonstrating volatile anesthetic-induced protection in isolated brain cells 1, 15, 20, 25, 30.

Figure 2.

Model for in vitro volatile anesthetic preconditioning of astrocytes. (A) Apparatus for in vitro anesthetic preconditioning: (a) anesthetic monitor, (b) medical air input, (c) gas line split with flow meters, (d) isoflurane vaporizer, (e) sham preconditioning (ShamPC) and isoflurane preconditioning (IsoPC) chambers, (f) charcoal filter for IsoPC chamber exhaust, (g) a gas line connection. Once the ShamPC and IsoPC chambers were filled with medical air and 5% CO2, with or without 3% isoflurane, these chambers were then clamped and disconnected from the air inputs and exhausts and placed into a standard 37°C incubator (not shown) during the 2 hour preconditioning period. (B) Schematic of the preconditioning treatment paradigm (“OGD,” oxygen and glucose deprivation).

OGD and cell death assessment

OGD and cell death quantification was carried out similarly as described 10. Astrocytes were rinsed twice in DMEM without glucose and supplements and placed in a chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Grass Lake, MI) deprived of oxygen (< 0 ppm) at 37 °C for 10 hours. Cells were then returned to normal growth conditions with normal growth media for 24 hours before cell death assessment. Cell death was determined indirectly from dead or damaged astrocytes by quantifying lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the culture media. The LDH assay was conducted according to the manufacture’s instructions (Roche, Basel Switzerland). Four to 6 replicate wells from each row, per sex, per preconditioning treatment were averaged to generate the percentage of LDH release that experiment. Two replicate wells in the control group (isoflurane preconditioning without OGD) were treated with 0.01% Triton X-100 to determine a maximum “100% LDH Release” value. LDH release was quantified using a Victor-3 plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Two-way ANOVA of the difference of paired means (i.e. “repeated measures”) was used for paired littermate analysis, comparing the factors of “preconditioning group” and “sex”. This analysis controlled for variability in absolute cell death values among cultures. The ANOVA compared innate cell sex-independent outcomes (pooled male and female cell death outcomes) and preconditioning-independent outcomes (pooled sham and isoflurane preconditioned cell death outcomes), followed by the Student Newman-Keuls post-hoc test to analyze differences between and within preconditioning and innate cell sex groups. Each culture from a given litter represented an n = 1; there was a total of 11 paired male and female cultures. *p < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using SigmaStat [version 2.0] software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

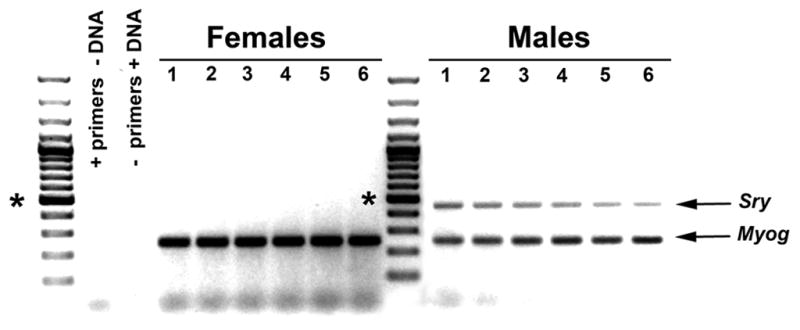

In male astrocytes, isoflurane preconditioning resulted in 32.9 ± 6.2% LDH release vs. 46.0 ± 6.6% LDH release in the sham preconditioned group (Figure 3A, *p < 0.05). In female astrocytes, isoflurane preconditioning resulted in 29.9 ± 3.6% LDH release vs. 44.2 ± 5.8% in the sham preconditioned group (Figure 3A, *p < 0.01). However, there was no significant difference between the 32.9% LDH release in the isoflurane preconditioned male astrocytes and the 29.9% LDH release in the isoflurane preconditioned female astrocytes, nor was there a significant difference between the 46.0% LDH release in sham preconditioned male astrocytes and the 44.2% LDH release in sham preconditioned female astrocytes. Within each sex, isoflurane preconditioning reduced OGD-induced cell death as assessed by LDH release from damaged or dead cells similarly in male and female astrocytes (Figure 3A, male, 13.0 ± 4.6% vs. female, 14.3 ± 5.2%, p = 0.86 for statistical interaction between preconditioning treatment and innate cell sex).

Figure 3.

Isoflurane preconditioning (IsoPC) reduced cell death as assessed by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release from damaged or dead cells in astrocytes independent of innate cell sex. (A) Mean LDH release from sham preconditioning (ShamPC) and IsoPC-treated male and female astrocytes (*p < 0.05 ShamPC vs. IsoPC in male cells, *p < 0.01 ShamPC vs. IsoPC in female cells; p = 0.86 for statistical interaction between preconditioning treatment and innate cell sex, n = 11). (B) Sex-independent paired difference analysis of LDH release between ShamPC and IsoPC groups. Each line connects cell death outcomes from the same litter (n = 1); * p < 0.01, n = 11. (C) Preconditioning-independent paired difference analysis of LDH release outcomes between male and female astrocytes. Each line connects the LDH release outcome from the same litter (n = 1); p = 0.52, n = 11.

The cell sex-independent analysis (pooled male and female cell death outcomes) showed that isoflurane preconditioning reduced LDH release 13.7 ± 3.4% compared to sham preconditioning regardless of innate cell sex (Figure 3B, sham preconditioning, 45.1 ± 5.5% vs. isoflurane preconditioning, 31.4 ± 4.5%; *p < 0.01). In contrast to the sex-independent reduction in cell death in isoflurane preconditioned astrocytes, the differences in LDH release as determined by the preconditioning-independent analysis (pooling the outcomes of the sham and isoflurane preconditioning groups) revealed no difference between male and female astrocytes (Figure 3C, male 39.4 ± 6.6% vs. female 37.0 ± 5.0%; n=11, p = 0.52).

Discussion

Using an in vitro model of isoflurane preconditioning and ischemia in isolated, sex-segregated primary astrocytes, we demonstrated two important findings: (1) isoflurane protects isolated astrocytes from OGD-induced cell death independent of innate cell sex, and (2) male and female astrocytes have similar cell death profiles following OGD independent of preconditioning treatment.

Previous reports investigating in vitro anesthetic preconditioning in brain cells have been limited to isolated neuron or glia/neuron mixed cultures which were not stratified by cell sex. In addition to using sex-segregated cultures, this report is the first to design an in vitro experimental paradigm to precondition isolated astrocytes with a volatile anesthetic. Since astrocytes are emerging as important contributors to the pathology of brain ischemia and subsequent brain degeneration 17–19, it is likely that astrocytes also play a role in processes that protect the brain, including those elicited by anesthetics and other forms of preconditioning 31. Hence, characterizing isoflurane and other forms of volatile anesthetic preconditioning in isolated astrocytes will provide a more complete assessment of the beneficial potential of anesthetics in the brain.

It is not surprising that astrocytes, like most cell types in the brain and other organs, are protected from an insult such as OGD if the cells are pre-exposed to a volatile anesthetic. For example, the protective preconditioning effect of volatile anesthetics has been demonstrated in neurons 11–15, cardiac cells 32, 33, epithelial cells 34, and kidney cells 35. Until now, however, no reports had considered innate cell sex in the response to anesthetics despite the sex differences reported in isoflurane preconditioning in vivo 1, 4, 5. Although isoflurane exposure itself has been shown to be neurotoxic in some experimental paradigms, the cytoprotective properties of isoflurane preconditioning in vivo and in vitro have typically been associated with lower isoflurane doses and shorter exposure times similar to what was used in the current study 1, 15, 20, 25, 30. For example, in vitro preconditioning with 1.2% or 2.4% isoflurane for 60 minutes was observed to be protective against the toxic consequences of continuous exposure to 2.4% isoflurane for 24 hours in rat primary cortical neuronal cultures.30 Furthermore, in this study, paired male and female control groups consisting of astrocytes exposed to isoflurane preconditioning alone with no OGD had less than 0.5% LDH release compared to male and female Triton X-100-treated controls. All of these observations would suggest that any intrinsic toxic effect of isoflurane exposure alone under the conditions utilized in this study did not likely contribute to the lack of innate cell sex differences observed in the response of astrocytes to isoflurane preconditioning and OGD.

Interestingly, the results presented here also show that cell death following OGD is similar between male and female astrocytes regardless of preconditioning treatment. This suggests that the in vivo sexual dimorphism resulting from isoflurane preconditioning, where females sustain exacerbated brain injury following isoflurane preconditioning and subsequent ischemia compared to the protection seen in males 3, is not likely a direct function of astrocyte cell sex and may instead be the result of neuron cell sex, multiple cell type interactions, and/or other physiologic factors in the brain such as circulating sex steroids. Indeed, differences in cell death mechanisms and outcomes have been observed between isolated male and female neurons 6–8, 36, but survival outcomes following an OGD insult were not tested in these studies.

In contrast to our findings, other studies have shown sex differences in cell death outcomes following OGD in isolated male and female astrocytes derived from rats and mouse strains different from the strain used here 9, 10. These studies, however, may not have removed non-adherent, mostly non-astrocytic cells following initial plating as was thoroughly done in this study, which could affect astrocyte purity and alter cell death outcomes. The presence or absence of phenol red, serum and other estrogen-like or estrogen containing media components in astrocyte or other types of cell culture that can act on sex steroid receptors and affect cell survival37 may also explain differences in cell sex-specific outcomes between our study and others. However, this is unlikely as we used similar media free of serum and phenol red free during OGD as was done in other studies in which sex differences were observed9, 10. It is also possible that the lack of sex differences observed in this study may be due to limitations in the measures used to detect cell death. In this study, LDH release was the only method used for evaluation of cell death outcomes. Our findings would be further strengthened had we observed similar outcomes using more than one method for detection of cell outcomes such as propidium iodide for cell death or calcein AM for cell survival. Regardless, the increasing number of reports demonstrating that differences in cell death mechanisms and outcomes can exist between isolated male and female cells is in itself a strong argument to consider innate cell sex when designing and interpreting in vitro data from primary cell systems.

Independent of preconditioning, the overall action of volatile anesthetics on astrocytes remains grossly understudied compared to neurons. Astrocytes dramatically influence synaptic transmission by regulating the extracellular milieu within the synaptic cleft 16, 17, thereby altering neuronal function. A small body of evidence suggests that volatile anesthetics can alter glutamate uptake and ionic stasis in astrocytes20, 21, 38 to an even greater extent than in neurons under some circumstances 20. Furthermore, we demonstrated in this study that isoflurane can alter the cell death outcome in male and female astrocytes. Hence, further characterization of the impact of volatile anesthetics like isoflurane on astrocytes as well as on neurons is imperative towards understanding the complicated, yet potentially beneficial effects of volatile anesthetics in the brain.

Finally, this report employed a two-way difference of paired means (“repeated measures”) ANOVA and post-hoc test as a statistical approach to normalize inherent variability in absolute cell death among cultures (i.e. between different litters). This approach differs from most reports which compare absolute cell death or survival values. While comparing absolute values is effective in low-variable settings, absolute cell death in primary cell cultures can be highly variable despite rigid procedural uniformity (as evident in Figures 3B & C). Therefore, analyzing the differences in paired cell death means within each culture internally controls for variability in absolute cell death, thus allowing for better resolution of differences when comparing across multiple cultures. Employing this type of analysis may illuminate potentially important, albeit otherwise overlooked data trends in investigations that take an in vitro approach to neurodegenerative research.

To our knowledge, we are one of the first laboratories to investigate anesthetic preconditioning in isolated astrocytes and to examine the role of innate cell sex in anesthetic preconditioning. We demonstrated that isoflurane preconditioning protects isolated cortical astrocytes from subsequent OGD. This protection is, however, independent of innate cell sex. These findings together with our previous report provide a more complete understanding of how cell type and cell sex may influence anesthetic preconditioning in the brain, and thereby how anesthetic choice may reduce ischemic brain damage in men and women at risk for perioperative stroke during cardiovascular surgeries.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rochelle Fu, Ph.D., Public Health & Preventative Medicine Department, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon, for her assistance with statistical analyses. This work was supported by grants from NIH/NINDS (NS054684 - SJM) and the Pacific Mountain Affiliate of the American Heart Association (Predoctoral Fellowship – DJ).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- ANOVA

nalysis of variance

- DNA

deoxyribose nucleic acid

- IsoPC

isoflurane preconditioning

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- OGD

oxygen-glucose deprivation

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- ShamPC

sham preconditioning

Contributor Information

Dustin Johnsen, Email: johnsend@ohsu.edu.

Stephanie J. Murphy, Email: murphyst@ohsu.edu.

References

- 1.Kitano H, Kirsch JR, Hurn PD, et al. Inhalational anesthetics as neuroprotectants or chemical preconditioning agents in ischemic brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1108–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L, Traystman RJ, Murphy SJ. Inhalational anesthetics as preconditioning agents in ischemic brain. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:104–10. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitano H, Young JM, Cheng J, et al. Gender-specific response to isoflurane preconditioning in focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1377–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu W, Wang L, Zhang L, et al. Isoflurane preconditioning neuroprotection in experimental focal stroke is androgen-dependent in male mice. Neuroscience. 2010;169:758–769. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L, Kitano H, Hurn PD, et al. Estradiol attenuates neuroprotective benefits of isoflurane preconditioning in ischemic mouse brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1824–1834. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du L. Innate gender-based proclivity in response to cytotoxicity and programmed cell death pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38563–38570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du L, Hickey R, Bayir H, et al. Starving neurons show sex difference in autophagy. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;284:2383–2396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804396200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heyer A, Hasselblatt M, von Ahsen N, et al. In vitro gender differences in neuronal survival on hypoxia and in 17beta-estradiol-mediated neuroprotection. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:427–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu M, Hurn PD, Roselli C, et al. Role of P450 aromatase in sex-specific astrocytic cell death. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:135–141. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu M, Oyarzabal E, Yang R, et al. A novel method for assessing sex-specific and genotype-specific response to injury in astrocyte culture. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;171:214–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaneko T, Yokoyama K, Makita K. Late preconditioning with isoflurane in cultured rat cortical neurones. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2005;95:662–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zitta K, Meybohm P, Bein B, et al. Cytoprotective effects of the volatile anesthetic sevoflurane are highly dependent on timing and duration of sevoflurane conditioning: Findings from a human, in-vitro hypoxia model. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2010;645:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bickler PE, Fahlman CS. The inhaled anesthetic, isoflurane, enhances Ca2+-dependent survival signaling in cortical neurons and modulates MAP kinases, apoptosis proteins and transcription factors during hypoxia. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2006;103:419–429. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000223671.49376.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velly L, Canas P, Guillet B, et al. Early anesthetic preconditioning in mixed cortical neuronal-glial cell cultures subjected to oxygen-glucose deprivation: the role of adenosine triphosphate dependent potassium channels and reactive oxygen species in sevoflurane-induced neuroprotection. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2009;108:955–963. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318193fee7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapinya KJ, Löwl D, Fütterer C, et al. Tolerance against ischemic neuronal injury can be induced by volatile anesthetics and is inducible NO synthase dependent. Stroke. 2002;33:1889–98. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000020092.41820.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nedergaard M, Ransom B, Goldman SA. New roles for astrocytes: redefining the functional architecture of the brain. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:523–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barres BA. The mystery and magic of glia: a perspective on their roles in health and disease. Neuron. 2008;60:430–440. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takano T, Oberheim N, Cotrina M, et al. Astrocytes and ischemic injury. Stroke. 2008;40:S8–S12. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.533166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossi D, Brady J, Mohr C. Astrocyte metabolism and signaling during brain ischemia. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1377–1386. doi: 10.1038/nn2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyazaki H, Nakamura Y, Arai T, et al. Increase of glutamate uptake in astrocytes: a possible mechanism of action of volatile anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:1359–66. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199706000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mantz J, Cordier J, Giaume C. Effects of general anesthetics on intercellular communications mediated by gap junctions between astrocytes in primary culture. Anesthesiology. 1993;78:892–901. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199305000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McClive PJ, Sinclair AH. Rapid DNA extraction and PCR-sexing of mouse embryos. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;60:225–6. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mcdougall S, Peters J, Labrant L, et al. Paired assessment of volatile anesthetic concentrations with synaptic actions recorded in vitro. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kudo M, Aono M, Lee Y, et al. Absence of direct antioxidant effects from volatile anesthetics in primary mixed neuronal-glial cultures. Anesthesiology. 2001;94:303–212. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200102000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li QF, Zhu YS, Jiang H. Isoflurane preconditioning activates HIF-1alpha, iNOS and Erk1/2 and protects against oxygen-glucose deprivation neuronal injury. Brain Res. 2008;1245:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bickler PE, Zhan X, Fahlman CS. Isoflurane preconditions hippocampal neurons against oxygen-glucose deprivation: role of intracellular Ca2+ and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:532–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200509000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mcmurtrey RJ, Zuo Z. Isoflurane preconditioning and postconditioning in rat hippocampal neurons. Brain Research. 2010:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wise-Faberowski L, Raizada MK, Sumners C. Oxygen and glucose deprivation-induced neuronal apoptosis is attenuated by halothane and isoflurane. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2001;93:1281–7. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200111000-00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franks NP, Lieb WR. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of general anaesthesia. Nature. 1994;367:607–14. doi: 10.1038/367607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei H, Liang G, Yang H. Isoflurane preconditioning inhibited isoflurane-induced neurotoxicity. Neurosci Lett. 2007;425:59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trendelenburg G, Dirnagl U. Neuroprotective role of astrocytes in cerebral ischemia: Focus on ischemic preconditioning. Glia. 2005;50:307–320. doi: 10.1002/glia.20204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaugg M, Lucchinetti E, Spahn DR, et al. Volatile anesthetics mimic cardiac preconditioning by priming the activation of mitochondrial K(ATP) channels via multiple signaling pathways. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:4–14. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200207000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sedlic F, Pravdic D, Ljubkovic M, et al. Differences in production of reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial uncoupling as events in the preconditioning signaling cascade between desflurane and sevoflurane. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2009;109:405–411. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181a93ad9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Annecke T, Chappell D, Chen C, et al. Sevoflurane preserves the endothelial glycocalyx against ischaemia-reperfusion injury. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2010;104:414–21. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma D, Lim T, Xu J, et al. Xenon preconditioning protects against renal ischemic-reperfusion injury via HIF-1alpha activation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:713–20. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carruth L, Reisert I, Arnold A. Sex chromosome genes directly affect brain sexual differentiation. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:933–934. doi: 10.1038/nn922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berthois Y, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. Phenol red in tissue culture media is a weak estrogen: implications concerning the study of estrogen-responsive cells in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:2496–500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chu K, Chiu C, Hsu T, et al. Functional identification of an outwardly rectifying pH- and anesthetic-sensitive leak K+ conductance in hippocampal astrocytes. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;32:725–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]