Abstract

One of the many challenges hindering the global response to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic is the difficulty of collecting reliable information about the populations most at risk for the disease. Thus, the authors empirically assessed a promising new method for estimating the sizes of most at-risk populations: the network scale-up method. Using 4 different data sources, 2 of which were from other researchers, the authors produced 5 estimates of the number of heavy drug users in Curitiba, Brazil. The authors found that the network scale-up and generalized network scale-up estimators produced estimates 5–10 times higher than estimates made using standard methods (the multiplier method and the direct estimation method using data from 2004 and 2010). Given that equally plausible methods produced such a wide range of results, the authors recommend that additional studies be undertaken to compare estimates based on the scale-up method with those made using other methods. If scale-up-based methods routinely produce higher estimates, this would suggest that scale-up-based methods are inappropriate for populations most at risk of HIV/AIDS or that standard methods may tend to underestimate the sizes of these populations.

Keywords: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, epidemiologic methods, HIV, network sampling, population size estimation, social networks

One of the challenges hindering the global response to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic is the difficulty of collecting reliable information about the populations most at risk. This information is difficult to collect because in many countries, HIV/AIDS risk is concentrated in populations—illicit drug users, female sex workers, and men who have sex with men—that are difficult to sample using standard statistical methods. The resulting lack of accurate, timely, and comprehensive information makes evidence-based approaches to targeting prevention programs and monitoring effectiveness difficult. Consider one of the most basic questions one might ask: How large are the most at-risk populations around the world, and how are the sizes of these populations changing over time? Despite enormous amounts of work carried out using a variety of methods, much uncertainty remains (1). For example, in many countries where injecting drug use has been reported, no reliable estimate of the number of drug injectors exists (2). Even the estimates that do exist are difficult to interpret because of methodological differences between countries and over time within countries (3). Similar uncertainties exist about the numbers of female sex workers and men who have sex with men (4–7).

One promising approach for estimating the sizes of groups most at risk of HIV infection is the network scale-up method, a technique that is new to epidemiology but has established roots in anthropology and social network analysis (8–10). The method uses information about the personal networks of a random sample of the general population to make size estimates, and it has a number of attractive features for global public health (10): 1) it can easily be standardized across countries and time because it requires a random sample of the general population, perhaps the most widely used sampling design in the world; 2) it can produce estimates of the sizes of many target populations in the same data collection, whereas many alternative methods require distinct data collections for each population of interest; 3) it can be partially self-validating because it can easily be applied to populations of known size; 4) depending on the sampling frame, it can produce estimates at either the city level or the national level, whereas many alternative methods can only be applied on 1 geographic scale; 5) it does not require respondents to report that they are members of a stigmatized group; and 6) it is relatively inexpensive and does not require extensive administrative records, which makes it feasible to use at frequent time intervals, even in middle- and low-income countries.

Despite these appealing characteristics, the applicability of the network scale-up method for global HIV/AIDS research remains unclear. Therefore, we empirically assessed the utility of the network scale-up method and the newer generalized network scale-up method in this context. Ideally, we would assess the accuracy of these scale-up-based estimates, but that is difficult, because for most at-risk populations we lack a “gold standard” size estimate. Therefore, we conducted our study in a most-at-risk population whose size had been estimated previously: heavy drug users in Curitiba, Brazil. Curitiba is an optimal location for this study because Brazil is a middle-income country with a concentrated HIV/AIDS epidemic and a strong governmental response to HIV/AIDS (11), and Curitiba, a city of 1.8 million people in southern Brazil, was the site of a 2004 Brazilian Ministry of Health study that yielded an estimate of the number of heavy drug users in the city. In addition to this previous estimate, we also estimated the number of heavy drug users in Curitiba using 2 standard methods: the multiplier method and the direct estimation method (12). These 3 estimates provided a background that we could use to assess the scale-up and generalized scale-up estimates. Thus, while most studies of hard-to-count populations produce only a single estimate, our study produced 5 different estimates based on 4 distinct data sources, 2 of which were from other researchers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The target population in our study was heavy drug users, defined as people who had used illegal drugs other than marijuana more than 25 times in the past 6 months. This target population is appropriate to the current state of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Brazil, where injecting drugs is unusual and heavy drug users show high rates of HIV infection relative to the general population (11).

Data sources

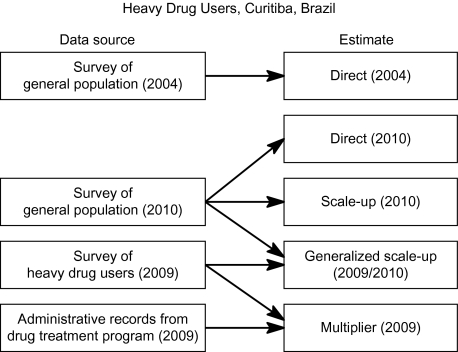

Our study used 4 data sources to produce 5 estimates, as summarized in Figure 1. One source of data, which were collected by our research team, was a face-to-face survey administered to a household-based random sample of 500 adult (i.e., aged ≥18 years) residents of Curitiba in 2010. The second source of data, also collected by our research team, was a respondent-driven sample (13–17) of 303 heavy drug users in Curitiba selected in 2009 (18, 19). The third source of data, collected by an independent group of researchers, was the 2004 Brazilian Ministry of Health PCAP survey (Pesquisa de Conhecimento, Atitudes e Práticas Relacionadas ao HIV/AIDS na População Brasileira), which measured the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of the Brazilian population with respect to HIV/AIDS (20). The final data source we used was administrative records from the Centro de Atenção Psicossocial (CAPS) drug treatment program in Curitiba. For more on the definitional consistency across these data sources, see the Web Appendix (http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/).

Figure 1.

Design of a study for estimating the number of heavy drug users in Curitiba, Brazil. Four distinct data sources, 2 of which were from other researchers, were used to produce 5 estimates.

Network scale-up method and generalized network scale-up method

The network scale-up method estimates population sizes using information about the personal networks of survey respondents under the assumption that personal networks are, on average, representative of the general population. For example, if a respondent reports knowing 2 illicit drug users and knows 200 people overall, we can estimate that 2/200, or 1%, of the population are illicit drug users. This estimate can be improved by averaging data over many respondents (9). The data needed for the network scale-up method come from interviews with a random sample of the general population. In addition to basic demographic questions, respondents are asked how many people they “know” in the target population. Following standard practice (10), in our study “know” was defined as follows: “You know them and they know you, and you have been in contact with them in the last 2 years.” Respondents are then asked a battery of questions to estimate the number of people they know (i.e., the size of their personal network).

From these survey data, one can estimate the size of the target population as

|

(1) |

where yi is the number of people known in the target population and is the estimated personal network size (9). Thus, one can view the network scale-up estimator as a generalization of the familiar sample proportion, which is the number of sample members in the target population divided by the sample size. The network scale-up estimator is instead the total number of target population members known by the respondents divided by the total number of people known by respondents.

In this context, the 2 methods most appropriate for estimating the total number of people known by each respondent are the known population method and the summation method (10). Because it was not clear a priori which method would produce more accurate estimates in this context, we used both methods in our study. Tests (described in the Web Appendix) showed that in this study, the data from the known population method were preferable, and therefore those data will be presented throughout.

The network scale-up method makes some strong implicit assumptions, and for that reason, we also collected the data needed for the generalized scale-up estimator. These data come from a sample of the target population—in this case, heavy drug users—and are then combined with the data from the general population to produce 2 correction factors: one for the lack of information flow and one for the differential network size between the target population and the general population. These correction factors and the procedures needed to estimate them are described in detail in the Web Appendix.

Direct estimation and multiplier method

For comparison with the scale-up and generalized scale-up estimates, we estimated the number of heavy drug users using 2 common methods: direct estimation and the multiplier method (12). Direct estimation involves asking a sample of the general population whether they are heavy drug users. The multiplier method estimates the size of the target population based on 2 pieces of information: 1) the number of people in the target population with some specific characteristic (e.g., the number of people in a specific drug treatment program) and 2) the estimated prevalence of that characteristic in the target population. This information is combined as follows:

| (2) |

where Nc is the number of people in the target population with that characteristic and  is the estimated proportion of the target population with that characteristic. In our study, Nc was the number of heavy drug users in a specific treatment program and

is the estimated proportion of the target population with that characteristic. In our study, Nc was the number of heavy drug users in a specific treatment program and  was the estimated proportion of heavy drug users who were in that program.

was the estimated proportion of heavy drug users who were in that program.

RESULTS

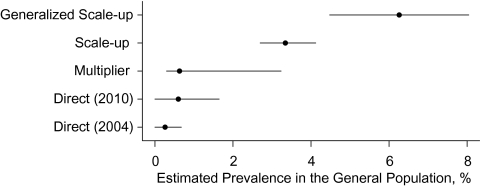

The results from all 5 estimates are presented in Figure 2 and described in detail below.

Figure 2.

Five estimates of the prevalence of heavy drug use in Curitiba, Brazil, 2004 and 2009–2010. Scale-up and generalized scale-up estimates were substantially higher than those obtained from standard methods (direct estimation and the multiplier method). Estimates of the number of heavy drug users in Curitiba ranged from 4,700 to 114,000. Bars, estimated 95% confidence interval.

Commonly used methods: direct estimation and multiplier method

We had 2 different sources of data for direct estimates. First, in 2004, the Brazilian Ministry of Health conducted the PCAP survey, which included approximately 1,000 people in Curitiba, and asked directly about the use of powder cocaine and injected cocaine. From these data, we estimated a prevalence of heavy drug use within the Curitiba population of 0.3% (95% confidence interval (CI): 0, 0.7) (see Web Appendix). In our 2010 survey of the general population, we produced a direct estimate of the prevalence of heavy drug use in the general population of 0.6% (95% CI: 0, 1.6) (see Web Appendix).

To produce our multiplier estimate, we learned from administrative records that 423 heavy drug users were enrolled in the CAPS drug treatment program in August 2009. We also estimated from our sample of heavy drug users (data collected in 2009) that 3.7% of heavy drug users were in the CAPS program (95% CI: 0.7, 7.8). Therefore, our multiplier estimate for the number of heavy drug users was 423/0.037 (see equation 2) or 11,459 people, which corresponds to 0.6% of the population (95% CI: 0.3, 3.2) (see Web Appendix). Thus, we see that these 2 commonly used methods produced similar estimates.

While this is somewhat reassuring, there are reasons to suspect that direct estimation and the multiplier method both produce underestimates. Direct estimates of the prevalence of drug use can be plagued by nonsampling error (21) and are suspected to be underestimates for 2 reasons (22). First, several studies that compared self-reported drug-use data with drug-testing data found that respondents underreport their drug use, in some cases substantially (23–25). Second, heavy drug users appear to be more difficult to reach in standard household surveys, which creates differential nonresponse (26, 27). For these reasons, some researchers place more confidence in “indirect” estimation methods, of which the multiplier method is an example (2). However, the multiplier-based estimates are only as good as the data used to create them. Multiplier methods will tend to produce underestimates if the members of the target population that appear in administrative data are overrepresented in the sample of the target population—akin to problems with capture-recapture when capture probabilities are correlated (28). For example, we suspect that participants in the CAPS treatment programs were overrepresented in our sample of heavy drug users, because middle- and upper-class heavy drug users were less likely to participate in CAPS (because it is a free government program) and less likely to participate in our respondent-driven sampling study (because the financial incentives for participation were less attractive for middle- and upper-class drug users). If this pattern did occur, these middle- and upper-class heavy drug users would be essentially invisible to the multiplier method.

Given these sources of concern about the commonly used methods, we now turn to another indirect method, the network scale-up method. By using information embedded in respondents’ personal networks, this method allows researchers to make indirect estimates that include people whose drug use is not recorded in any administrative records.

Network scale-up method and generalized network scale-up method

Respondents in our general population survey reported knowing a total of 3,075 heavy drug users in Curitiba. Further, we estimated that our respondents knew a total of 92,003 people in Curitiba. Therefore, the scale-up estimator produced an estimated proportion of heavy drug users of 3.3% (95% CI: 2.7, 4.1) (see Web Appendix).

The generalized network scale-up estimator relaxes 2 assumptions of the network scale-up estimator. It relaxes both the assumption that people are aware of everything about the people they are connected to and the assumption that the target population has the same average personal network size as the population as a whole. As we describe in more detail in the Web Appendix, we estimated the 2 necessary correction factors using data from our sample of heavy drug users and produced a generalized scale-up estimate of the proportion of heavy drug users of 6.3% (95% CI: 4.5, 8.0).

DISCUSSION

The estimates derived from the network scale-up method and the generalized network scale-up method were substantially higher than those from standard methods (Figure 2). However, our scale-up-based estimates of drug use are roughly comparable to those of previous national-level studies in Brazil and international benchmarks (see Web Appendix). Further, because the scale-up method allows researchers to estimate the sizes of multiple target populations, our study also estimated the number of female sex workers and men who have sex with men in Curitiba. We find that these estimates too are roughly comparable with those of other studies from Brazil and international meta-analysis (see Web Appendix). We caution, however, that all of these comparisons have a large degree of uncertainty because of differences between the studies and ambiguities in the definitions of the target populations.

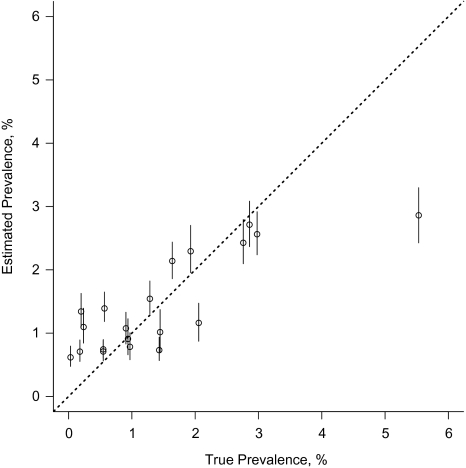

Although these consistency checks are somewhat encouraging, they cannot assess the accuracy of the estimates. Therefore, as a final check, we note that we also asked respondents how many people they knew in 20 populations of known size—for example, women who have given birth in the last 12 months, students enrolled in public universities, and employees of the city of Curitiba (see the Web Appendix for a list of the 20 populations). Therefore, to assess the network scale-up method, we estimated the size of each of these populations using our sample and the scale-up estimator (equation 1). Figure 3 reveals that for most of the 20 populations, the size estimates, while not perfect, were quite reasonable. However, Figure 3 also reveals a tendency to overestimate the sizes of smaller populations and underestimate the sizes of larger populations, a finding that is consistent with previous studies (29, 30). The fact that this exact estimator in this exact sample can produce reasonable estimates for quantities we can check gives us some additional confidence about the estimates for quantities we cannot check.

Figure 3.

Validation of network scale-up estimates for 20 populations of known size in Curitiba, Brazil, 2010. (A list of the 20 populations is presented in the Web Appendix.) The estimates were generally similar to the true values, but there was a tendency to overestimate the sizes of small groups and underestimate the sizes of large groups, a pattern that has been observed in other scale-up studies as well (29, 30). The purported 95% confidence intervals also had poor coverage properties. The 1 outlier in the plot represents the group “middle school students in a public school.” Bars, estimated 95% confidence interval.

Estimates made in populations of known size also reveal that the estimated 95% confidence intervals, which in this case were generated using a bootstrap procedure accounting for our 2-stage cluster sample design (see Web Appendix), are not wide enough: The purported 95% confidence intervals have an empirical coverage rate of 25%. While this is somewhat discouraging, it is also exciting that we can actually detect this problem (we suspect that the confidence intervals for many comparable methods are also too small, but this problem is largely invisible). Therefore, we suggest that in future research, investigators also address nonsampling sources of uncertainty, such as those introduced by response bias or recall errors.

Because the scale-up-based estimates were so much higher than those obtained with existing methods, we considered many possible sources of error that might have inflated our estimates (of course, as explained above, there are reasons to suspect that the standard estimates are too low). One possible source of overestimation could be the order of the questions in our survey: Heavy drug users were the first group asked about, and this might have led to inflated responses. However, no effects of question order were found in a previous telephone-based network scale-up survey in Italy (31). Unfortunately, we were unable to randomize the order of our questions for logistical reasons, so we cannot address this possibility directly with our data. We recommend that future researchers randomize the order of the questions if possible.

An alternative explanation for these apparently high estimates is that some interviewers may not have followed the study protocol. More specifically, rather than asking, “How many people do you know who live in Curitiba and have used illegal drugs other than marijuana more than 25 times in the last 6 months (i.e., average of once a week)?,” some interviewers could have shortened the question to, “How many people do you know that use drugs?”. This shorter question could have produced much higher responses that would have led to a higher estimated population size. Although we had no reason to believe that this occurred, we assessed the robustness of our estimates to data from a single interviewer by systematically dropping the data collected by each of our 9 interviewers. This analysis showed that no particular interviewer had a large effect on the estimate (see Web Appendix).

An additional source of upward bias is “drug use inflation,” that is, respondents’ including in their answers people who used drugs but did not use them heavily enough to match our study criteria. For example, if a respondent knew someone who drank alcohol every day, the respondent might have included this person in his or her count even though that person did not match our study criteria. In fact, a previous survey in Brazil suggests that this “drug use inflation” might occur: Approximately 20% of respondents reported that someone who drank alcohol twice per week was at severe risk due to substance misuse, and almost half of respondents reported that someone who had used marijuana once or twice in his/her lifetime was at severe risk due to substance misuse (32). The differences between this previous survey and our study prevent any firm conclusions, but these previous results at least suggest that “drug use inflation” might have occurred in our survey; this will have to be a topic for future research.

A further possible source of error in the scale-up estimates is problems with the sampling frame. If residents of Curitiba differ in their propensity to know heavy drug users (30) and if the sampling frame was less likely to include persons with higher propensities to know heavy drug users (possibly the homeless), then our scale-up estimates could be too low. Conversely, if the sampling frame systematically excluded persons who have a lower propensity to know heavy drug users (possibly those living in gated communities), then our scale-up estimates could be too high. The relative magnitude of these problems is difficult to assess empirically, and the sensitivity of the network scale-up method to sampling frame problems is an important question for future research.

Prior to data collection, we expected that the scale-up-based estimates might be higher than those made with other methods, but we did not expect them to be so much higher. As was described above, we suspect that direct estimates and multiplier estimates will be too low in our setting (and possibly in many other settings). However, the generalized scale-up method, which we believe is more statistically appropriate than the scale-up method, produced estimates that were much higher than expected. Since these equally plausible methods produced such different results, we recommend that in additional studies investigators compare scale-up-based estimates with those made using other methods; conducting additional scale-up studies without having results from other methods for comparison will not address this challenge.

Fortunately, our research design (Figure 1) can be easily replicated in other settings. In many cities, there are routine behavioral surveillance surveys of populations most at risk of HIV/AIDS, and there are routine studies involving samples taken from the general population. In this case, by adding a few additional questions to each data collection effort, investigators can replicate our study at virtually no cost. Further, our research design could be enriched with additional sources of data and additional estimation methods. For example, distributing a unique object to members of the target population before sampling from the target population could produce a capture-recapture estimate (33), although some features of the target population sampling—in this case, respondent-driven sampling—may complicate this approach (17, 33–36). Other sources of administrative data, such as HIV registry data, could be used to produce additional multiplier method estimates (37), but the accuracy of these estimates will depend on the availability of administrative data and possible statistical dependencies between data sources. An additional variation in design would be to use alternative sampling methods to reach the target population (e.g., time-location sampling).

If additional studies are undertaken and it is found that scale-up-based methods routinely produce higher estimates than existing methods, scale-up-based methods may not be appropriate for estimating the sizes of populations most at risk of HIV/AIDS. Alternatively, it may be the case that existing methods have been systematically underestimating the sizes of these populations. At this point, we do not have enough evidence to definitively address this important possibility.

Procedures used for prevention, management, and treatment of HIV/AIDS in Brazil are recognized worldwide as a benchmark for other middle-income countries. However, Brazil is an emergent country with a growing population and competing health priorities (38). Human and material resources in Brazil and in other countries should be mobilized in the most equitable way possible, on the basis of sound empirical evidence. Therefore, estimates of the sizes of the groups most at risk of HIV/AIDS should be as accurate as possible. The present study shows that scale-up-based estimators are a promising alternative to commonly used approaches, but more research is needed. General, standardizable, and cost-effective approaches to collecting data about the most-at-risk groups are necessary for the formulation of evidence-based policies designed to curb the spread of HIV/AIDS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Author affiliations: Department of Sociology and Office of Population Research, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey (Matthew J. Salganik); CEDEPLAR, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil (Dimitri Fazito); and FIOCRUZ, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Neilane Bertoni, Alexandre H. Abdo, Maeve B. Mello, Francisco I. Bastos).

This research was supported by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, the Brazilian Ministry of Health, a CAPES/Fulbright fellowship (F. I. B.), the US National Science Foundation (grant CNS-0905086 to M. J. S.), and the US Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant R01HD062366 to M. J. S.).

The authors thank Dr. M. Mahy, Dr. R. Lyerla, Dr. H. R. Bernard, Dr. C. McCarty, Dr. T. Zheng, Dr. T. McCormick, K. Levy, and D. Feehan for helpful comments. They also thank Dr. A. R. P. Pascom, M. L. Vettorazzi, Dr. S. T. Moyses, D. Blitzkow, C. H. Venetikides, and M. Thomaz for assistance. Finally, the authors thank the Curitiba Municipal Health Secretariat/CAPS for sharing data about the drug treatment program.

The opinions expressed here represent the views of the authors and not the funding agencies.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AIDS

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- CAPS

Centro de Atenção Psicossocial

- CI

confidence interval

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- PCAP

Pesquisa de Conhecimento, Atitudes e Práticas Relacionadas ao HIV/AIDS na População Brasileira de 15 a 54 Anos de Idade

References

- 1.Brookmeyer R. Measuring the HIV/AIDS epidemic: approaches and challenges. Epidemiol Rev. 2010;32(1):26–37. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxq002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, et al. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet. 2008;372(9651):1733–1745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathers B, Cook C, Degenhardt L. Improving the data to strengthen the global response to HIV among people who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(2):100–102. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baral S, Sifakis F, Cleghorn F, et al. Elevated risk for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries 2000–2006: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4(12):e339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040339. (doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040339) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cáceres C, Konda K, Pecheny M, et al. Estimating the number of men who have sex with men in low and middle income countries. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(suppl 3):iii3–iii9. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.019489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cáceres CF, Konda K, Segura ER, et al. Epidemiology of male same-sex behaviour and associated sexual health indicators in low- and middle-income countries: 2003–2007 estimates. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(suppl 1):i49–i56. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.030569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vandepitte J, Lyerla R, Dallabetta G, et al. Estimates of the number of female sex workers in different regions of the world. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(suppl 3):iii18–iii25. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.020081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernard HR, Johnsen EC, Killworth PD, et al. Estimating the size of an average personal network and of an event subpopulation: some empirical results. Soc Sci Res. 1991;20(2):109–121. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Killworth PD, McCarty C, Bernard HR, et al. Estimation of seroprevalence, rape, and homelessness in the United States using a social network approach. Eval Rev. 1998;22(2):289–308. doi: 10.1177/0193841X9802200205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernard HR, Hallett T, Iovita A, et al. Counting hard-to-count populations: the network scale-up method for public health. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(suppl 2):ii11–ii15. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.044446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malta M, Magnanini MM, Mello MB, et al. HIV prevalence among female sex workers, drug users and men who have sex with men in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):317. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-317. (doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-317) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Estimating the Size of Populations at Risk for HIV. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling II: deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 2002;49(1):11–34. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 1997;44(2):174–199. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salganik MJ, Heckathorn DD. Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociol Methodol. 2004;34(1):193–239. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volz E, Heckathorn DD. Probability-based estimation theory for respondent-driven sampling. J Off Stat. 2008;24(1):79–97. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goel S, Salganik MJ. Respondent-driven sampling as Markov chain Monte Carlo. Stat Med. 2009;28(17):2202–2229. doi: 10.1002/sim.3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bastos FI, Malta M, Albuquerque EM, et al. Taxas de Infecção de HIV e Sífilis e Inventário de Conhecimento, Atitudes e Práticas de Risco Relacionadas Às Infecções Sexualmente Transmissíveis Entre Usuários de Drogas em 10 Municípios Brasileiros. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Oswaldo Cruz Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salganik MJ, Mello MB, Abdo AH, et al. The game of contacts: estimating the social visibility of groups. Soc Networks. 2011;33(1):70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szwarcwald CL, Barbosa-Júnior A, Pascom AR, et al. Knowledge, practices and behaviours related to HIV transmission among the Brazilian population in the 15–54 years age group, 2004. AIDS. 2005;19(suppl 4):S51–S58. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000191491.66736.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner CF, Lessler JT, Gfroerer JG, editors. Survey Measurement of Drug Use: Methodological Studies. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manksi CF, Pepper JV, Petrie CV. Informing America’s Policy on Illegal Drugs: What We Don’t Know Keeps Hurting Us. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fendrich M, Johnson TP, Sudman S, et al. Validity of drug use reporting in a high-risk community sample: a comparison of cocaine and heroin survey reports with hair tests. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(10):955–962. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colón HM, Robles RR, Sahai H. The validity of drug use responses in a household survey in Puerto Rico: comparison of survey responses of cocaine and heroin use with hair tests. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(5):1042–1049. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.5.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delaney-Black V, Chiodo LM, Hannigan JH, et al. Just say “I don’t”: lack of concordance between teen report and biological measures of drug use. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):887–893. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caspar RA. Survey Measurement of Drug Use: Methodological Studies. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1992. Follow-up of nonrespondents in 1990; pp. 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao J, Stockwell T, Macdonald S. Non-response bias in alcohol and drug population surveys. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009;28(6):648–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hook EB, Regal RR. Capture-recapture methods in epidemiology: methods and limitations. Epidemiol Rev. 1995;17(2):243–264. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Killworth PD, McCarty C, Bernard HR, et al. Two interpretations of reports of knowledge of subpopulation sizes. Soc Networks. 2003;25(2):141–160. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng T, Salganik MJ, Gelman A. How many people do you know in prison?: using overdispersion in count data to estimate social structure in networks. J Am Stat Assoc. 2006;101(474):409–423. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snidero S, Zobec F, Berchialla P, et al. Question order and interviewer effects in CATI scale-up surveys. Sociol Method Res. 2009;38(2):287–305. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Secretaria Nacional de Políticas sobre Drogas. Relatório Brasileiro sobre Drogas. Brasília, Brazil: Secretaria Nacional de Políticas sobre Drogas; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paz-Bailey G, Jacobson JO, Guardado ME, et al. How many men who have sex with men and female sex workers live in El Salvador? Using respondent-driven sampling and capture-recapture to estimate population sizes. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(4):279–282. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.045633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berchenko Y, Frost SD. Capture-recapture methods and respondent-driven sampling: their potential and limitations. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(4):267–268. doi: 10.1136/sti.2011.049171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gile K, Handcock M. Respondent-driven sampling: an assessment of current methodology. Sociol Methodol. 2010;40(1):285–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9531.2010.01223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goel S, Salganik MJ. Assessing respondent-driven sampling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(15):6743–6747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000261107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heimer R, White E. Estimation of the number of injection drug users in St. Petersburg, Russia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;109(1–3):79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Victora CG, Barreto ML, do Carmo Leal M, et al. Health conditions and health-policy innovations in Brazil: the way forward. Lancet. 2011;377(9782):2042–2053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60055-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.