Abstract

The authors examined the effects of welfare programs that increased maternal employment and family income on the development of very young children using data from 5 random-assignment experiments. The children were 6 months to 3 years old when their mothers entered the programs; cognitive and behavioral outcomes were measured 2–5 years later. While there were no overall program impacts, positive or negative, on the development of children in this age group, there was a pair of domain- and age-specific effects: The programs decreased positive social behavior among 1-year-olds and increased school achievement among 2-year-olds. After exploring several explanations for these results, the authors suggest that the contextual changes engendered by the programs, including children's exposure to center-based child care, interacted differentially with specific developmental transitions.

Keywords: welfare reform, infants and toddlers, stage–environment fit, maternal employment

Over the last decade, a new body of research has emerged that provides a rich understanding of the effects of welfare and employment policies on children and adolescents (Chase-Lansdale et al., 2003; Morris, Huston, Duncan, Crosby, & Bos, 2001; Zaslow et al., 2002). Experiments conducted in the United States and Canada indicate that welfare policies that increase maternal employment and family income benefit preschool-aged children but have negative effects on adolescent's school progress (Gennetian, Duncan, Knox, Clark-Kauffman, & Vargas, 2002; Gennetian & Miller, 2000; Morris et al., 2001; Morris, Duncan, & Clark-Kauffman, 2005). Less attention has been paid to understanding welfare policy effects on infants and toddlers, despite the fact that parents of these youngest children are no longer universally exempt from welfare work requirements (as they were prior to 1996). In this study, we attempted to address that gap by examining the outcomes of children ages 6 months to 3 years in five experimental welfare reform programs conducted in the 1990s.

Early childhood is a period of rapid and consequential growth in physical, cognitive, and socioemotional abilities, making infants and toddlers highly sensitive to changes in parents' employment and income (McCall, 1981; Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000; Thompson, 2001). In prior studies of welfare reform, researchers have examined young children as a group and have often excluded those under 2 years (Chase-Lansdale et al., 2003; Morris et al., 2005; Morris & Michalopoulos, 2003; Zaslow, McGroder, & Moore, 2000). Yet, both developmental theory and studies of maternal employment and child well-being suggest that the effects of such programs may vary across early childhood. Transitions from infancy to toddlerhood and from toddlerhood to preschool include distinct qualitative leaps in development, many of which are relevant to children's abilities to cope with maternal separation and nonparental child care. Maternal employment, for instance, is associated with small negative effects on cognition for children under 12 months but neutral or positive effects on toddlers and preschool-aged children (for review, see Waldfogel, 2002).

In the present study, we examined the effects of parents' random assignment to employment-based welfare programs on the cognitive and behavioral outcomes of children in different developmental periods of early childhood. In addition to estimating the impacts of welfare programs on this critical and understudied age group, this study contributes to researchers' understanding of how family income moderates and mediates the effects of maternal employment on children. We relied on experimental programs that supplemented parents' earnings to estimate directly the effects of maternal employment accompanied by increases in income.

Using data from multiple experimental studies provides not only the strongest possible basis for causal inference but also results that can be generalized to diverse contexts. However, our ability to understand the pathways of any effects we observe was constrained by the fact that the mediators themselves are not randomly assigned to families. For this reason, our analysis of the mediating mechanisms of program impacts is exploratory in nature. Also, because in this study we tested the effects of programs designed to increase parents' employment and income, the results cannot be applied to many existing welfare policies that may result in income loss.

Background

The Effects of Maternal Employment on Infants and Toddlers in Low-Income Families

An increasingly large and rigorous set of studies indicate that maternal employment, particularly full-time work, in the 1st year of a child's life is associated with modest decreases in cognitive ability measured during middle childhood (Baum, 2003; Berger, Hill, & Waldfogel 2005; Blau & Grossberg, 1992; Hill, Waldfogel, Brooks-Gunn, & Han, 2005; James-Burdumy, 2005; Ruhm, 2004). In contrast, maternal work after the 1st year and continuously in the first 3 years has been related to higher scores on reading and math tests (Blau & Grossberg, 1992; Han, Waldfogel, & Brooks-Gunn, 2001; James-Burdumy, 2005; Waldfogel, Han, & Brooks-Gunn, 2002). Young children's behavior is much less consistently associated with their mother's employment status, although in a few studies children whose mothers began working in their 1st or 2nd year of life later exhibited slightly higher levels of noncompliance (Belsky & Eggebeen, 1991; Harvey, 1999) or behavior problems (Baydar & Brooks-Gunn, 1991).

Income and other measures of socioeconomic advantage appear to moderate the effects of maternal employment on children's outcomes, but the nature of this relationship is not well understood. The negative effect of maternal employment on infants' later cognition is often limited to or larger for more advantaged children—Whites, those in two-parent homes, and those in higher income households (Baydar & Brooks-Gunn, 1991; Brooks-Gunn, Han, & Waldfogel, 2002; Desai, Chase-Lansdale, & Michael, 1989s; Waldfogel et al., 2002).1 In samples of low-income families, some studies show that children benefit from their mother's employment (Alessandri, 1992; Jackson, 2003; Vandell & Ramanan, 1992) and many more associate consecutive years of unemployment, job loss, and welfare receipt with detrimental effects on children's health (Secret & Peck-Heath, 2004), behavior (Dunifon, Kalil, & Danziger, 2003; Smith, Brooks-Gunn, Klebanov, & Lee, 2000), and cognitive test scores or educational attainment (Kalil & Ziol-Guest, 2005; Kornberger, Fast, & Williamson, 2001; Ku & Plotnick, 2003; Randolph, Rose, Fraser, & Orthner, 2004; Smith et al., 2000). Both observational studies and evaluations of experimental welfare programs suggest that maternal employment is most likely to benefit low-income preschool-aged children if it increases family income (Dearing, McCartney, & Taylor, 2006; Kalil, Dunifon, & Danziger, 2001; Morris et al., 2001, 2005). Yet, most of these studies do not include infants and toddlers or estimate effects for this age group separately.

Income is also a likely mediator of the effects of maternal employment on children's development. Incremental changes in income are proportionally larger for low-income families and appear to be more consequential for the development of poor children than for other children (Dearing et al., 2006; Duncan, Yeung, Brooks-Gun, & Smith, 1998ss; Mistry, Vandewater, Huston, & McLoyd, 2002; Votruba-Drzal, 2006). In addition, poverty is most detrimental for children when experienced early in life, suggesting that increases in income from maternal employment may be particularly beneficial for low-income infants and toddlers (Bolger, Patterson, Thompson, & Kupersmidt, 1995; Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997; Duncan et al., 1998; Klerman, 1991; Korenman & Miller, 1997; McLoyd, 1998).

The use and effects of nonparental child care, another key mediator of maternal employment effects on children, may also differ by socioeconomic status. Compared to other children, low-income preschoolers are less likely to be placed in center-based care (Capizzano & Adams, 2004; Ehrle, Adams, & Tout, 2001) and, while in care, they receive less cognitive stimulation and fewer positive interactions with adults (Dowsett, Huston, Imes, & Gennetian, 2008). It has also been suggested, although not consistently shown, that stimulating and sensitive child care environments may buffer children from the effects of poverty by compensating for inadequacies in home environments (Caughy, DiPietro, & Strobino, 1994; McCartney, Dearing, Taylor, & Bub, 2007). Several studies find that children in low-income families experience particularly large cognitive benefits of high-quality nonpa-rental care or preschool (Campbell, Ramey, Pungello, Sparlin, & Miller-Johnson, 2002; Caughy et al., 1994; McCartney et al., 2007; Schweinhart, Barnes, & Weikart, 1997), but others find no differences in the effects of the type or quality of child care by family income (Burchinal, Peisner-Feinberg, Bryant, & Clifford, 2000; sNICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2000; Votruba-Drzal, Coley, & Chase-Lansdale, 2004).

In addition to income and child care, maternal employment may also affect children indirectly through parental well-being, but it is difficult to predict the direction of these effects. Studies of both Depression-era and modern families support McLoyd's (1990) theory that the effects of economic hardship on children's development operate through less sensitive parenting practices associated with parental stress and mental health problems (e.g., Conger et al., 1992; Elder, 1974; Elder, Eccles, Ardelt, & Lord, 1995; McLoyd, Jayartne, Ceballo, & Borquez, 1994; Mistry et al., 2002). It follows that if maternal employment improves the economic well-being of the family, it may lead to benefits such as decreased stress and depression in parents, increased parental warmth, and more positive interactions between parent and child. However, single mothers are disproportionately employed in low-quality jobs—characterized by low pay, limited benefits, and nonstandard hours (Dunifon, Kalil, & Bajracharya, 2005; Guyer & Mann, 1999; Johnson & Corcoran, 2003; Presser & Cox, 1997)—which may not reduce economic deprivation and could be detrimental to both parental and child well-being (Han, 2005; Joshi & Bogen, 2007; Parcel & Menaghan, 1994, 1997s; Presser, 2003; Raver, 2003).

Developmental Tasks in Infancy and Toddlerhood

Developmental theory provides a strong rationale for expecting children's responses to changes in parents' employment and income to vary by age and developmental stage. Ecological and life course perspectives suggest that human development is shaped by interactions between child and environment, and by the timing of life experiences (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998; Eccles et al., 1993; Elder, 1998; McCall, 1981). The ecology of development is made up of multiple, interacting contexts of a child's life—from culture to family, schools, and peers—the importance of which may differ over the lifetime (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; McCall, 1981). In addition, it has been argued that changes to these contexts may fit better with certain developmental stages than others (Eccles & Midgley 1989; Eccles et al., 1993) and that developmental trajectories may be more vulnerable to environmental changes during certain transitional periods, such as puberty (Graber & Brooks-Gunn, 1996).

Researchers studying poverty's effects on children have generally focused on early childhood as a period of “unique opportunity and vulnerability” (Thompson, 2001, p. 32). It is believed that environmental factors are most likely to shape children's development during this time of rapid change in physical, cognitive, and psychosocial capacities (McLoyd, 1998; Smith, Brooks-Gunn, & Klebanov, 1997; Thompson, 2001). Within this period, major developmental shifts occur at the transitions from infancy to toddlerhood and from toddlerhood to the preschool years (the timing of these transitions varies considerably by child). While development in infancy is characterized by attachment and the creation of safe, trusting relationships with caretakers, toddlerhood pits the desire to maintain those relationships against the child's emerging independence (Erikson, 1963). The process of becoming an autonomous individual—a confluence of physical, cognitive, and socio-emotional changes—is one of the key features of development for toddlers and preschoolers (Erikson, 1963; Harter, 1998; Jacobs, Bleeker, & Costantino, 2003; Mahler, 1979). A child's specific phase in these developmental processes is likely to affect his–her ability to handle separation from parents and to benefit from the social experiences available in child care environments.

Children's emotion regulatory skills, which develop by leaps and bounds over the first few years of life, are likely to be particularly critical to how children respond to parents' increases in employment and whether the resulting parental separations are met with gains or setbacks in their developmental trajectories. In early infancy, children use emotional expressions to regulate the behavior of their caregivers (distress signals and smiling), and they develop the most basic forms of regulation, such as developing sleep–wake cycles (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000). By the end of the 1st year, children use social referencing skills to access information from caregivers to determine the appropriate emotional response (Campos & Stenberg, 1981), and by the middle of the second year, toddlers begin to use strategies for effective behavioral regulation for managing emotions, such as avoiding situations that increase negative emotions and using reassuring speech (Bretherton, Fritz, Zahnwaxler, & Ridgeway, 1986; Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000).

These skills become increasingly effective in the transition to the preschool period, as children begin recognizing emotions in others, using words to articulate their feelings, and using quite sophisticated strategies to manage their emotions and behavior (Harris, 1993; Saarni, 1999). Part of the leap in the 3rd year is the achievement of children's self-development, the use of “I” and its associated self-referent emotions (e.g., shame, pride, embarrassment; Lewis, 1993). Simultaneously with the development of emotion regulation comes executive function skills (particularly effortful control) that allow children to inhibit their natural reaction (Rothbart, Posner, & Hershey, 1995; Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000).

In addition to changes across the 1-, 2-, and 3-year-old transition points (which roughly correspond to the infancy, toddlerhood, and preschool transitions, respectively), research suggests that the 18-to 24-month period may be an important marker for a series of important changes in children's development. The first clear signs of self–other development (the recognition of oneself in a mirror) occur around 18 months, with increased development in this area as children approach the age of 2 years (Asendorpf, Warkentin, & Baudonneire, 1996; Harter, 1998; Jacobs et al., 2003; Lewis & Brooks-Gunn, 1979; Nelson & Fivush, 2004). A child's ability to understand parents' goals as separate from their own is dependent on this development. Children of this age also experience an eruption in language development (Fenson et al., 1994; Reznick & Goldfield, 1992), which contributes to their emerging self-regulatory abilities (Dunn, Bretherton, & Munn, 1987; Grolnick, Bridges, & Connell, 1996). Separation anxiety also often peaks midway through the 2nd year of life as a result of developing abilities to differentiate attachment figures (from others) and to understand that they exist even when out of sight (object permanence; Bolby, 1982; Piaget, 1937/1954).

What are the implications of this review for the current study? In the prior literature of the effects of maternal employment on outcomes for children, researchers have focused on the 1st year of life as a key developmental period in which the effects of maternal employment can be negative (e.g., Brooks-Gunn et al., 2002; Han et al., 2001). While we agree that the youngest children in this age range may be most at risk for negative effects of maternal employment, we made several more specific hypotheses:

In the case of the experimental programs that increased maternal employment and family income, the effects on even the youngest children in low-income families are likely to be neutral, if not positive.

Transitions from toddlerhood to the preschool period are also potentially important and even the 18-month to 24-month period may be qualitatively different than earlier in the 2nd year or the beginning of the 3rd year. Based on the developmental tasks of these transitions, we expect that 2- and 3-year-old children may be better able than 1-year-olds to weather or even benefit from the changes to mother– child time and nonparental child care engendered by employment.

While we cannot fully examine mediating pathways of program impacts on children, we expect that increases in center-based child care are a likely mechanism of any effects we observe. Past research in this area suggests we may see positive effects on cognitive development among 2- and 3-year-olds, who are more likely to be in center-based care.

Method

The Studies

Our analysis used data from five random-assignment evaluations of welfare reform programs implemented in the United States and Canada. All were implemented in the mid- to late 1990s (prior to U.S. federal welfare reforms) as experimental demonstrations of programs designed to increase parental employment and reduce welfare receipt. None intervened directly in parents' mental health or parenting or in children's outcomes. Table 1 shows the studies in more detail. (For more information on the individual studies, see Bloom et al., 2000, 2002; Bos et al., 1999; Gennetian & Miller, 2000; Huston et al., 2003; Michalopoulos et al., 2002; Morris & Michalopoulos, 2000.)

Table 1. Description of the Experimental Studies Included in This Analysis.

| Study | Programs tested | Sites | Follow-up period(s) (in years) | Core program components | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work requirements | Earnings supplement | Expanded child care assistance | Time limits | ||||

| Connecticut Jobs First | 1 | New Haven, CT; Manchester, CT | 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Florida's Family Transition Program | 1 | Escambia County, FL | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Minnesota Family Investment Program (MFIP) | 2a | Seven counties in Minnesota | 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| New Hope Project | 1 | Milwaukee, WI | 2 and 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Canadian Self-Sufficiency Project (SSP) | 2b | New Brunswick British Columbia | 3 and 4.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

The MFIP evaluation tested one program with work mandates and one without.

SSP tested one program with work mandates and another with work mandates and assistance finding employment

Despite diverse geographic locations, the studies had many common design features. As shown in Table 1, programs rarely included a single component; instead, as with welfare programs implemented in many states today, they mixed and matched these components together. All five sought to make work pay by offering income disregards or income supplements (both of which have the effect of decreasing the marginal tax rate on earnings) to employed participants. The generosity of the earning supplement varied by the program. For example, under Florida's Family Transition Program (FTP), the first $200 plus one half of any remaining earned income was disregarded (i.e., not counted) in calculating a family's monthly grant. However, the effect of FTP's disregard on recipients' income was limited by Florida's relatively low welfare grant levels (a maximum of $303 for a family of three). The supplements of the Canadian Self-Sufficiency Project (SSP), by contrast, were significantly more generous, supplementing earnings by half the difference between a participant's actual earnings and a target level of earnings (set at about $25,000).

In addition to supplementing income, all but one program (New Hope) mandated employment by conditioning welfare benefits on participation in employment-related activities, such as job searching, job training, and employment. These mandates were enforced through sanctions, which resulted in reduced benefit levels in the event of nonparticipation. Two programs (Connecticut Jobs First and FTP) also encouraged work by setting limits on the length of time parents could receive their welfare benefits. Finally, FTP, Minnesota Family Investment Program, and New Hope provided expanded child care assistance, making it easier for parents to purchase child care through some combination of subsidies, direct payment to child care providers, promotion of center-based child care, and access to child care resource and referral services.

In each study, sample members were randomly assigned either to a program group (we use this term interchangeably with experimental or treatment group) that was subject to a new set of welfare rules or to a control group that received the standard benefits available to Aid to Families with Dependent Children recipients and low-income families. In four of the five studies, parents were applying for welfare or renewing eligibility when they were randomly assigned, and receipt of welfare included participation in the study effort (i.e., random assignment and collection of administrative data). The exceptions include New Hope, in which all low-income parents within a geographic region were eligible to participate on a voluntary basis, and SSP, in which welfare recipients were given the option to participate (99% agreed to do so). Parents could opt out of the survey effort associated with each evaluation, although response rates in all studies were quite high—between 71% and 90%. Extensive analyses conducted as part of the original studies established that on a variety of baseline parental and family characteristics, differences between program and control groups were extremely rare, suggesting that any differences in outcomes between the groups after random assignment can be attributed to the program, rather than other differences between families (Bloom et al., 2000, 2002; Bos et al., 1999; Gennetian & Miller, 2000; Morris & Michalopoulos, 2000).

The Sample

Beginning with all observations of children whose parents participated in one of the five studies, we narrowed the sample to children who were between 6 and 47 months old at the time of random assignment. We would have liked to include children 0–5 months old, but the sample of children in this age range was insufficiently large and concentrated in a single program.2 Our analysis used three separate but overlapping samples of children corresponding to the three outcome measures of interest. The panels of Table 2 present the sample sizes by outcome measure for 1-year age groups. While the behavior samples were virtually identical in size, the achievement sample was larger both in the number of children included and the number of observations per child. The samples included multiple observations per child if a study either measured outcomes at two intervals or, in the case of child achievement, collected measures of the outcome from multiple sources (parent and teacher report, or test score).3

Table 2. Sample Sizes by Child's Age at Baseline (in Years) and Outcome Measure.

| Age at baseline(in years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit of analysis | Under 1a | 1 | 2 | 3 | Total |

| Achievement | |||||

| Observationsb | 204 | 1,781 | 2,707 | 3,062 | 7,754 |

| Children | 171 | 1,183 | 1,926 | 1,945 | 5,223 |

| Families | 169 | 1,161 | 1,903 | 1,908 | 4,580c |

|

| |||||

| Positive social behavior | |||||

| Observationsb | 157 | 1,382 | 2,011 | 1,841 | 5,391 |

| Children | 132 | 942 | 1,515 | 1,381 | 3,969 |

| Families | 132 | 932 | 1,509 | 1,369 | 3,698c |

|

| |||||

| Problem behavior | |||||

| Observationsb | 158 | 1,387 | 2,017 | 1,853 | 5,415 |

| Children | 132 | 942 | 1,515 | 1,386 | 3,974 |

| Families | 132 | 932 | 1,509 | 1,374 | 3,705c |

This category includes children 6–11 months in age at random assignment. There were insufficient numbers of children under 6 months to include in these analyses.

There were multiple observations per child if the study either measured outcomes at two follow-up points or collected multiple measures of achievement (from parent, teacher, and test) per child.

This row does not sum to the total because some families contributed children in multiple age groups.

Table 3 shows means and standard deviations of the baseline demographic variables used in our analysis for the full sample of children from the five studies that had one or more of the three outcome measures and separately by experimental group. At the time of random assignment, the children were living primarily in single-parent families, most of whom had been receiving welfare for 5 or more years, but fewer than 1 in 10 had been born to teenage mothers. Slightly more than one third of children had mothers who worked for pay in the year prior to random assignment, and a little over half of the parents had received a high school diploma. On average, children in this study were 2.5 years old at the time of random assignment and 6.3 years at the time of assessment. As expected with an experimental design, differences between program and control groups are uncommon and small.

Table 3. Proportions and Mean Values of Baseline Characteristics for Full Analytic Sample and by Treatment Status.

| Baseline characteristic | Full sample | Experimental group | Control group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent demographics | |||

| Age | 26.62 (5.56) | 26.52 (5.51) | 26.73 (5.62) |

| Teenager at time of child's birth | .09 | .09 | .08 |

| Race | |||

| Black | .24 | .24 | .24 |

| White | .58 | .58 | .57 |

| Latino | .07 | .07 | .06 |

| Other | .12 | .11 | .13 |

| Marital status | |||

| Never married | .66 | .67 | .65 |

| Separated–divorced | .32 | .31 | .32 |

| Married | .02 | .01 | .02 |

| Parent education, employment, and income | |||

| High school graduate | .56 | .57 | .55 |

| Employed in year prior to random assignment | .37 | .37 | .37 |

| Earnings in year prior to random assignment ($1,000) | 1.75 (4.33) | 1.73 (4.11) | 1.76 (4.52) |

| Years on A FDC prior to random assignment | |||

| 0–2 | .07 | .07 | .06 |

| 2–5 | .27 | .25 | .29 |

| 5+ | .67 | .67 | .64 |

| Child and family characteristics | |||

| Child's age at random assignment (in years) | 2.54 (0.89) | 2.56 (0.88) | 2.52 (0.89) |

| Child age at follow-up (in years) | 6.34 (1.15) | 6.34 (1.14) | 6.34 (1.15) |

| Number of children in family | 2.06 (1.11) | 2.05 (1.11) | 2.06 (1.12) |

| Child has younger sibling | .21 | .21 | .21 |

| Age of youngest child in family (in years) | 1.85 (1.26) | 1.88 (1.29) | 1.83 (1.23) |

| N | 7,040 | 3,671 | 3,369 |

Note. Standard deviations of continuous measures are in parentheses. This table reports baseline characteristics for the sample inclusive of all children who had a nonmissing value for any one (or more) of the three outcome measures. Maximum sample sizes are shown; exact sample sizes vary by the amount of missing data in each variable. AFDC = Aid to Families with Dependent Children.

Relative to the population of welfare recipients at the time of federal welfare reforms and currently, the characteristics of the sample most closely match longer term welfare recipients or stayers, as they are sometimes called. More than 90% of this sample had been on cash assistance for 2 or more years at the time of random assignment, while this was true for only about half of cash assistance recipients in the late 1990s and even less (40%) by 2002. Similar to this sample, among stayers in 2002, 56% had at least a high school diploma and 34% were employed for pay (Zedlewski & Alderson 2001; Zedlewski, 2003). These characteristics are not dissimilar from those of individuals who move on and off welfare regularly, but they do make this sample more disadvantaged than new welfare applicants.

Measures

The measurement of the variables used in the analysis is described below. In the case of multi-item scales, we present the range of Cronbach coefficient alphas for the five studies in parentheses.

Child age

We computed child age at the point of random assignment from birth date information provided on the parent surveys and program information on the date the family was randomly assigned. For the purposes of this analysis, we created four age categories: under 1 year old (6–11 months), 1 year old (12–23 months), 2 years old (24–35 months), and 3 years old (36–47 months). Age of assessment ranged from 3 to 10 years (M = 6.3; SD = 1.1) depending on the child's age at random assignment and the timing of each study's follow-up. We grouped children by age at random assignment (rather than at follow-up) because prior analyses of these programs indicated that the largest impacts on parental employment and family income occurred shortly after random assignment.

Achievement-cognitive outcomes

We measured children's cognitive performance or school achievement using parent reports, teacher reports, and test scores, all collected at the time of follow-up, with some studies including multiple sources per child, and two of the studies assessing children at multiple times. All studies included parent reports of children's achievement on a single-item 5-point rating of how well the child was doing in school (or preschool; Bloom et al., 2000, 2002; Bos et al., 1999; Gennetian & Miller, 2000; Morris & Michalopoulos, 2000). Teacher assessment of achievement (collected in three of the studies) was based on 10 items from the Academic subscale of the Social Skills Rating System (Gresham & Elliot, 1990), comparing the child's performance with that of other students in the classroom on reading and math skills, intellectual functioning, motivation, oral communication, classroom behavior, and parental encouragement (α = .94).

In the 36-month follow-up of SSP, children took the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—Revised (Morris & Michalopoulos, 2000) and a math skills test containing a subset of items from the Canadian Achievement Tests, Second Edition (Morris & Michalopoulos, 2000). Both are well-validated, reliable tests of children's cognitive performance. Observations of achievement-cognition for children assessed at ages 3 or 4 (n = 571), when they were less likely to be enrolled in formal schooling, were most often test scores collected as part of the SSP study. Missing data were more prevalent among the youngest children in the sample; 19% had no achievement–cognition measure compared to 4% of those children assessed at age five or older.

Behavioral outcomes

Parents reported children's problem behavior at follow-up using the Behavior Problems Index (a 28-item scale; α = .69−.92; Peterson & Zill, 1986). The Behavior Problems Index includes internally reliable subscales of internalizing (e.g., “appears lonely” or “acts sad and depressed”) and externalizing (e.g., “is aggressive toward people or objects” or “has temper tantrums”) behaviors. Mothers also completed either the full 25-item Positive Behavior Scale (Polit, 1996; α = .90−.95) or an abbreviated version of seven items. Similar to the Social Skills Rating System, items on this scale assess child compliance–self-control, social competence and sensitivity, and autonomy. These two behavior measures do not capture opposite ends of a single dimension. The correlation between measures of problem and positive social behavior is negative but not large (−.30; p < .01).

To provide comparability in child outcomes across measures and studies, we standardized achievement and behavioral outcomes using study-specific, control-group standard deviations. This approach is comparable to effect size calculations commonly used in power analyses and the interpretation of program impacts (Cohen, 1988, 1992) and has been used in similar studies of child interventions (Anderson, 2005). Standardized outcomes were obtained with the following formula:

in which Ỹ is the standardized observation of outcome Y for child i in study p, Yip is the unstandardized observatio n of outcome Y for child i in study p, Y̅p is the full sample mean for measure Y in study p, and s is the control group standard deviation for measure Y in study p, sypc and Control group standard deviations are used because it is conceivable that the treatment affected the sample variance of outcome measures.

Earnings, welfare receipt, and income

For the U.S. studies, we used state unemployment insurance records of quarterly earnings, state administrative records of monthly cash assistance and food stamp benefits, and program records of earnings supplement receipt. For the Canadian study, we computed earnings using parents' reports of hourly wages, hours worked per week, and weeks worked per month in surveys. Administrative records provided information on receipt of income assistance, Canada's welfare program, and SSP supplement payments. We used these data to create yearly earnings, welfare, and income variables, which were then averaged over the first 2 years of follow-up and adjusted to 2001 dollars using the Consumer Price Index. Yearly income was calculated as the sum of earnings, earnings supplements, and welfare and food stamp payments. Canadian dollars were converted to American dollars before being adjusted for inflation.

Child care type

In follow-up surveys, study participants reported the types of nonmaternal child care they used in previous months. The exact wording of child care questions differed by study, but all asked whether anyone other than the participant had cared for the child regularly (often defined as at least once a week for at least a month) in a specified period preceding the survey. If the respondent answered “yes” to this question, they were then asked an open-ended question about types of child care provider(s). For the purposes of our analyses, we collapsed responses to the second question into two main categories: any center based (child care center, Head Start, after-school program, or summer program) and any home based (other parent, respondent's spouse-partner, grandparent, sibling, or babysitter).

The child care setting measure has several important limitations. While the other measures used in this analysis were collected for every child in the home, information on child care type was collected only for the identified focal child of each family (N = 4,492). In addition, the time period for which respondents reported child care usage differed by study. Depending on the study, the follow-up interviews were conducted between 2 and 5 years after random assignment (see Table 1), and the respondents were asked to list child care providers in a 12- to 36-month period prior to the interview.

Maternal depression

In the follow-up interviews, parents were asked about the number of days they had experienced each of 20 depressive symptoms, using items from the Center for Epidemiology Studies—Depression scale (one study used a shortened, 11-item version of the scale; Radloff, 1977). We created a summary scale score (α = .82 –.91).

Warm parenting

Mothers self-reported parental warmth using a three-item scale assessing the frequency with which the child was shown praise, received attention, and was involved in special activities with the parent. This scale was developed in the Canadian evaluation of SSP and adopted in the other studies (Statistics Canada, 1995). Items were scored on a 4- to 6-point scale, depending on the study, and averaged for a total scale (α = .57 − .82). This measure was not collected in the 54-month follow-up of SSP.

Control variables

Our models control for a set of baseline family characteristics collected either from an information form filled out by the participant prior to random assignment or from administrative records. Those variables are years on Aid to Families with Dependent Children (0–2, 2–5, 5 or more), family earnings (in $1,000 units) in the year prior to random assignment, family earnings squared in the year prior to random assignment, whether mother was employed in the year prior random assignment (0 or 1), whether mother has a high school diploma (0 or 1), mother's marital status (never married, married, separated), number of children in the family, age of youngest child in the family (in years), mother's race (Black, White, Latino, other), and whether the mother was under the age of 18 when the child was born (0 or 1).

Study-level controls include dichotomous variables for each study (and for sites in the case of two studies that were implemented in diverse regions) and a continuous measure of follow-up length. In the models predicting achievement, we also controlled for source of report (parent, teacher, or test).

Analytic Approach

Pooled data

The analyses reported in this article were conducted on a pooled data set of baseline characteristics and parent and child outcomes from all five studies. This analytic approach draws on the strengths of both experimental and meta-analytic techniques to provide confident estimates of program impacts that can be generalized to a broader set of welfare and employment policies. The seven programs were all designed with a similar overarching goal in mind (to increase employment among low-income, primarily welfare-recipient parents) and collected comparable measures of parent and child outcomes but were implemented in diverse geographic locations. For these reasons, a synthesis of their findings can provide powerful evidence about how changes to family circumstances brought about by welfare reforms affected children.

Meta-analysis is the most common statistical approach to synthesizing findings from multiple studies on the same topic. The strengths and weakness of this approach have been well documented (Cooper & Hedges, 1994; Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). Under certain assumptions (about the relation between covariates and outcomes across sites and samples), pooling data produces nearly identical results to meta-analytic techniques while providing substantially more analytic flexibly (Morris et al., 2005). The large size of the pooled sample permitted us to test the sensitivity of the models to multiple specifications and to test whether age differences in experimental impacts are accounted for by differences in impacts by family and parent characteristics associated with child age. In effect, by pooling data across comparable studies, we hoped to draw broader conclusions typically only possible with meta-analysis, while using estimation strategies only possible with individual-level observations. Our aggregation of study findings is appropriate because these studies can be viewed as a representative sample of a larger population of policy interventions (Cooper & Hedges, 1994). Even the Canadian program, SSP, has been shown to have very similar effects to comparably designed American programs (Berlin, 2000), despite any differences in the policy and economic context of the two countries.

Models

We calculated program impacts as the difference between the average outcomes for treatment and control group children using ordinary least squares regression techniques to adjust for baseline covariates. In the first model, the independent variable of interest was treatment status (a binary variable was coded 1 if the parent was in the experimental group). In the second model, we allowed the treatment effect to vary by child's age within each study by controlling for all but one of the age group dummy variables and estimating the effects of all of the Age × Treatment interaction groups (excluding the main effect term for treatment group). With this formulation, coefficients on each of the Age × Treatment interaction terms represented experimental–control group differences by age when we controlled for baseline characteristics.

We also undertook a limited examination of five potential mediating processes—welfare receipt, family income, child care setting, parental depression, and parental warmth. These factors were selected because they have been linked theoretically and empirically to child development, were targeted (directly or indirectly) by the programs, and were measured consistently across the studies. Because measures of all five potential mediators were collected after random assignment, they could not be included directly in our estimation model of child impacts without threatening the internal validity of our results (Duncan, Magnuson, & Ludwig, 2004; Gennetian, Morris, Bos, & Bloom, 2005; Gennetian, Magnuson, & Morris, 2008).4

Instead, we conducted two alternative analyses that offer insight into the likely pathways of program impacts on children. In the first, we substituted each potential mediator as the dependent variable in the main estimation model described above. This method produced unbiased estimates of program impacts on each potential pathway, thereby providing partial evidence of the existence (or lack) of a mediating relationship. If, for instance, the programs did not affect family income, it would be reasonable to conclude that family income did not mediate program impacts on children. More specifically, if program impacts on family income did not vary by child age, it is unlikely that income was a key pathway determining any differential effects on children of different ages. This approach is consistent with previous research examining the pathways of effects of experimental welfare and employment programs on children (Gennetian & Miller, 2002; Huston et al., 2001; Morris et al., 2005; Morris & Michalopoulos, 2003).

The use of data pooled from multiple studies limits the scope of our estimation of program impacts on potential mediators. For instance, we examined only one measure each of parental well-being and parenting because those are the measures for which we had consistent data across all five studies. Our analysis of child care was most constrained because it was limited to measures of child care setting (e.g., center-based care vs. home-based care) collected on only a subset of children in the sample.

For this reason, and given the strong theoretical support for child care as a potential mediator, we took a second approach to exploring the role of child care. In this analysis, we leveraged a policy difference between the programs, whether they provided standard or expanded child care assistance, in order to estimate the moderating effect of child care assistance on program impacts on children. Three programs in this study offered expanded child care assistance, which helped parents obtain and pay for center-based child care. Prior work using the same data showed that expanded assistance increased the use of center-based child care, while standard assistance increased the use of family-based child care (Gennetian, Crosby, Huston, & Lowe, 2004). We estimated program impacts on children, by age, as a function of this program component. With this approach, evidence of child care being a pathway of program impacts on children would be manifested as stronger impacts on children in programs that provided expanded child care assistance.

In all models, heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors were used to account for nonindependence between observations of children within the same family and between multiple observations of the same child (White, 1980). We examined the extent to which assuming nonindependence within children or families changed the results; results were very similar with either approach. Our regressions clustered observations by family, allowing for correlations between observations within a family while maintaining the assumption of independence for observations across families.

Results

Regression Estimates of Program Impacts on Child Outcomes

We first used ordinary least squares regression techniques to estimate program impacts on child school achievement, positive social behavior, and problem behavior for the full sample of children ages 6–47 months. There were no statistically significant differences between the program and control group children on any of the three outcome measures (results not shown).

Next, we estimated the age-specific impacts of the program treatment on those same outcomes using 1-year age groups (see Table 4). In keeping with the neutral impacts for the full age range, there were limited impacts on child outcomes by age. There were no statistically significant differences between the average experimental and control group reports of problem behavior for any subgroup of children. In addition, the programs did not affect any of the measured outcomes for children who were under 1 year old or for children who were 3 years old.

Table 4. Regression-Adjusted Program Impacts on Child Outcomes by Child Age at Random Assignment.

| Program impacts by child age | Achievement | Positive social behavior | Problem behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under age 1a | 0.043 (0.140) | 0.037 (0.163) | −0.229 (0.186) |

| Age 1 | −0.061 (0.054) | −0.177** (0.058) | −0.007 (0.060) |

| Age 2 | 0.093* (0.041) | 0.053 (0.046) | 0.045 (0.051) |

| Age 3 | 0.044 (0.044) | 0.007 (0.051) | 0.002 (0.056) |

| R2 | .027 | .027 | .013 |

| F | |||

| Overall model | 5.60** | 4.72** | 2.68** |

| Equality of coefficientsb | 1.80 | 3.46* | 0.77 |

| N | 7,593 | 5,325 | 5,347 |

Note. The coefficients presented in this table were based on standardized outcome measures and can therefore be interpreted as standard deviation differences between the program and control groups for children in the given age range. Standard errors are in parentheses. Models controlled for study-site dummies and the following baseline characteristics: follow-up length, prior earnings, prior earnings2, prior Aid to Families With Dependent Children receipt, prior years of employment, high school degree, teen parent, marital status, number of children, age of youngest child in family, and race. The achievement model also included controls for the source of the measure.

This category includes children 6-11 months in age at random assignment. There were insufficient numbers of children under 6 months to include in this analysis.

A significant F statistic for the equality of coefficients indicates a rejection of the null hypothesis that all coefficients presented in the column are equal to one another.

p < .05.

p < .01.

There were, however, some small but significant effects of maternal participation in these programs on achievement and positive social behavior for children ages 1 and 2. Positive behavior of children age 1 (12–23 months) at the time of random assignment was negatively affected by mother's assignment to the treatment group. The difference in parent-reported positive social behavior was just under one fifth of a standard deviation and statistically significant. In contrast, 2-year-old children, ages 24–35 months, experienced gains in school achievement due to assignment to the program group. This statistically significant effect was also small—a .09 standard deviation change.

These two impacts are significantly different from zero, but are they significantly different from the other Age × Treatment interactions in the model? Table 4 presents F statistics testing the equality of coefficients—whether the parameter estimates for the four interactions between age and treatment status were equal to one another. The null hypothesis that there were no statistically significant differences between those four coefficients can be rejected only in the case of positive social behavior (p < .05), in which the coefficient for 1-year-olds is significantly different than that of 2-year-olds (p < .01) and 3-year-olds (p < .05).

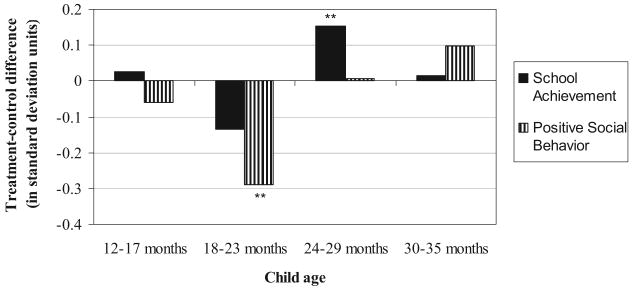

We hypothesized that impacts on children from these programs might center on the 18- to 24-month age range, when key developmental tasks might be particularly salient in moderating how children respond to changes in maternal employment and nonparental care. To test this directly, we narrowed our sample to children 1–2 years of age and estimated age-specific program impacts on school achievement and positive social behavior using 6-month age groups. The results of these analyses, shown in Figure 1, provide some evidence in support of our hypothesis.

Figure 1.

Program impacts on later school achievement and positive social behavior of 1- and 2-year-olds by 6-month age groupings. * p < .01.

The statistically significant program impacts on 1- and 2-year-olds are highly concentrated (in reverse directions) between 18 and 29 months. What was estimated in our main models as a -.18 standard deviation impact on positive social behavior among 1-year-olds is shown here to reflect the average of an insignificant impact on 12- to 17-month-olds and a significant negative impact on 18- to 23-month-olds of nearly one third of a standard deviation. In this specification, we also estimated a negative impact on school achievement of 18- to 23-month olds, which approached statistical significance. Similarly, these analyses suggest that the improvement on school achievement among 2-year-olds estimated in our main models occurred primarily among 24- to 29-month-olds.

We conducted a set of tests to explore the sensitivity of these results to alternative models specifications. These tests limited the analytic sample in ways that could reasonably be expected to influence our estimation of experimental impacts, including the length of follow-up, whether the study had observations in all four age groups, and whether the study was conducted in the United States or Canada. In addition, we tested whether the results were affected by the inclusion of siblings using a sample of 1 randomly selected child per family. We also tested the sensitivity of the program impacts on school achievement to the source of achievement measures, parent report or test score. In total, we ran seven alternative models of program impacts on child school achievement and five of impacts on positive social behavior.

By and large, the pair of program impacts on 1- and 2-year-old children was robust to these tests, although in a few cases the magnitude of the coefficients drops sufficiently to lose statistical significance. Statistically significant impacts on positive social behavior among 1-year-olds ranged in size from –.13 to –.22, and impacts on the later school achievement of 2-year-olds ranged from .09 to .12 standard deviations. When the Canadian study, SSP, was excluded, both impacts were insignificant, although still in the same direction. In addition, the positive impact on school achievement among 2-year-olds was sensitive to the source of the outcome measure and the follow-up length. When estimated using test scores only or using longer follow-up measures only (4–5 years as opposed to 2–3 years), the coefficient size drops to .06 and becomes insignificant.

Regression Estimates of Program Impacts on Potential Pathways

Next, we examined a set of pathways through which the program treatments may have affected child outcomes differently by age. Each potential mediator was used as the dependent variable in a regression of three of the four age groups, the four Age × Experiment interactions, and the same set of control variables used in our main analyses. With these analyses, we looked specifically for any indication that the programs' impacts on any of these mediating processes differed for families with 1-year-olds versus families with 2-year-olds in order to shed light on the differential program impacts on these age groups of children.

The estimated program impacts on family welfare receipt, earnings, and income by child age are shown in the first three columns of Table 5. We found no evidence that program impacts on these direct targets of the intervention varied by child age. In general, welfare receipt declined and earnings and income increased for the treatment group relative to the control group, regardless of child age.

Table 5. Regression-Adjusted Program Impacts on Parental Outcomes by Child Age at Random Assignment.

| Program impacts by child age | Welfare receipt | Earnings | Income | Maternal depression | Parental warmth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under age 1a | −0.620 (0.399) | 1.578** (0.474) | 1.978** (0.515) | −0.060 (0.178) | 0.180 (0.212) |

| Age 1 | −0.473** (0.175) | 0.643* (0.266) | 1.067** (0.274) | −0.071 (0.058) | −0.162* (0.070) |

| Age 2 | −0.192 (0.145) | 0.884** (0.214) | 1.500** (0.208) | −0.026 (0.050) | −0.044 (0.058) |

| Age 3 | −0.289* (0.145) | 0.552* (0.230) | 1.168** (0.220) | 0.049 (0.052) | −0.022 (0.062) |

| R2 | .492 | .290 | .285 | .017 | .030 |

| F | |||||

| Overall model | 180.38** | 53.14** | 64.66** | 2.65** | 3.93** |

| Equality of coefficientsb | 0.81 | 1.54 | 1.32 | 0.94 | 1.33 |

| N | 6,884 | 6,864 | 6,864 | 5,309 | 3,448 |

Note. Standard errors are in parentheses. Models controlled for study-site dummies and the following baseline characteristics: follow-up length, prior earnings, prior earnings2, prior Aid to Families with Dependent Children receipt, prior years of employment, high school degree, teen parent, marital status, number of children, age of youngest child in family, and race.

This category includes children 6–11 months in age at random assignment. There were insufficient numbers of children under 6 months to include in this analysis.

A significant F statistic for the equality of coefficients indicates a rejection of the null hypothesis that all coefficients presented in the column are equal to one another.

p < .05.

p < .01.

The final two columns of Table 5 show the regression estimates of program impacts on maternal depression and parental warmth, aspects of parental well-being and parenting that are thought to mediate the effects of maternal employment on children. There was only one statistically significant difference by age of child; the programs had a small (.16 standard deviations; p < .05) negative impact on parental warmth among parents with 1-year-olds.

Table 6 shows the extent to which patterns of child care use might help explain the few significant program impacts on children. We present estimates of program impacts on child care settings by child age and treatment status. The programs increased the use of nonmaternal care for children ages 1, 2, and 3; treatment group focal children were more likely to have been at a child care center, or other center-based child care setting, than control group children of the same age. There was no statistically significant difference between treatment and control group children under the age of 1, in part because the subgroup is too small for precise estimation. The significant impacts are not large; among 2-year-olds, for example, the .361 regression coefficient on any center-based care indicates that the programs increased the probability of 2-year-olds being in center-based care by 8 percentage points from 33% to 41%. If parents of 2-year-olds were more likely than parents of 1-year-olds to increase the use of center-based child care because of the program, it might partially explain the direction of program impacts on these two age groups. However, there is no evidence that program impacts on child care use differed for these age groups. While the impact on center-based care among 1-year-olds is not statistically significant, the size of the estimate (.278) is also not significantly different from the estimate for 2-year-olds.

Table 6. Regression-Adjusted Program Impacts on Child Care Setting by Child Age at Random Assignment (Logistic Regressions).

| Program impacts by child age | Any nonmaternal care | Any center-baseda | Any home-basedb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under age 1c | −0.013 (0.397) | −0.452 (0.465) | 0.167 (0.385) |

| Age 1 | 0.209 (0.148) | 0.278 (0.161) | −0.034 (0.135) |

| Age 2 | 0.347** (0.131) | 0.361** (0.118) | 0.143 (0.111) |

| Age 3 | 0.409** (0.136) | 0.254* (0.125) | 0.220 (0.119) |

| Pseudo R2 | .203 | .139 | .115 |

| χ2 | |||

| Overall model | 631.03** | 578.73** | 565.37** |

| Equality of coefficientsd | 1.74 | 2.99 | 2.09 |

| N | 4,492 | 4,489 | 4,511 |

Note. Standard errors are in parentheses. Models controlled for study-site dummies and the following baseline characteristics: follow-up length, prior earnings, prior earnings2, prior Aid to Families With Dependent Children receipt, prior years of employment, high school degree, teen parent, marital status, number of children, age of youngest child in family, and race.

Center-based child care includes care provided in a child care center, an extended day program at a school or community organization, and summer programs.

Home-based child care includes care provided by a relative, the mother's spouse or partner, or a nonrelative babysitter.

This category includes children 6–11 months in age at random assignment. There were insufficient numbers of children under 6 months to include in this analysis.

A significant chi-square statistic for the equality of coefficients indicates a rejection of the null hypothesis that all coefficients presented in the column are equal to one another.

p < .05.

p < .01.

In analysis not shown here, we further examined the potential mediating relationship of child care by estimating program impacts on child achievement and positive social behavior as a function of whether the parent participated in a program with standard or expanded child care. As noted above, programs with expanded child care provided services that made it easier for parents to purchase child care and consequently had larger impacts on the use of center-based child care. If increases in the use of center-based child care might partially explain the few program impacts on young children, then we expected the pattern of effects to be limited to or stronger for the programs that provided expanded child care. Instead, the direction of the coefficient on positive social behavior for 1-year-olds and on achievement for 2-year-olds was the same and the magnitude differed very little as a function of the intensity of child care assistance (results available from Heather D. Hill).

Discussion

This study adds to the growing evidence that programs aimed at moving welfare recipients into employment have few effects, positive or negative, on child achievement or behavior. We show this to be the case even among the youngest children, those thought to be most sensitive to environmental changes, and even when maternal employment leads to increases in family income. Some may find it surprising that such seemingly significant changes in family life have so few effects on children, particularly infants and toddlers. However, these results are in keeping with a large body of research showing only scattered age- and domain-specific effects of maternal employment on early childhood development (for review, see Waldfogel, 2002).

While we had a limited sample of children less than 12 months old, the lack of significant program impacts on this age group is consistent with our hypothesis that we would find neutral or positive effects on even the youngest children in low-income families if employment was accompanied by increases in family income. Our second hypothesis was that 1- and 2-year-olds might be at key developmental transition points that could be affected differentially by increases in maternal employment and that those children 2 years and older might be better equipped to weather or benefit from that change than 1-year-olds. Somewhat consistent with these expectations, we found a modest negative program impact on positive social behavior for 1-year-old children, concentrated almost entirely among children in the latter half of their 2nd year of life. In addition, the programs positively affected school achievement among 2-year-olds, specifically those 24–29 months. Contrary to our expectations, however, the positive effect on 2-year-olds did not extend to older preschool children. We consider both the impacts on school achievement and positive social behavior that we observed to be modest in size.

This pattern of program impacts suggests that the environmental changes associated with maternal employment may be more complementary with certain periods of children's development than others. This explanation is consistent with the developmental concepts of stage–environment fit (Eccles et al., 1993) and the sensitivity of developmental transitions (Graber & Brooks-Gunn 1996), as well as advances in brain research, which support the notion of plasticity at key developmental periods to changes in parents' employment (Shonkoff & Philips, 2000). The goodness of fit between contextual changes and developmental periods reflects not only whether children's developmental needs are being met but also whether they have the skills to meet the demands of their changing contexts (Graber & Brooks-Gunn, 1996).

While previously applied primarily to the study of behavioral patterns in the transition from childhood to adolescence, these concepts also have relevance to early childhood, as the findings presented here suggest. Just as Graber and Brooks-Gunn (1996) pointed to the collection of transitions and life events that occur within the period of adolescence, we argue (and find evidence) that early childhood has a set of distinct transitions—from infancy to toddlerhood and from toddlerhood to preschool—that may interact with contextual changes to affect behavioral or cognitive development differentially across these periods.

We anticipated finding some evidence that differences in child care settings or the intensity of child care assistance provided to parents would explain the differential effects on 1- and 2-year-olds. While we found no differences in the use of center-based child care by child age, the stage–environment fit perspective suggests that the increases in center-based care experienced by treatment group children of all ages may have interacted with developmental transitions to produce neutral, positive, or negative effects, depending on the child's stage of development.

For instance, entering or increasing time spent in center-based child care during the transition from infancy to toddlerhood in the 2nd year of life may present a unique challenge to children engaged in an intense period of burgeoning social skills. Developments in locomotion and language in the 2nd year of life greatly increase the potential for children's interactions with peers and the beginning of interpersonal relationships (Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker 2006). This is a positive development but one that is not without conflict and stress for the child. Social interactions call upon emotional and regulation skills that are in flux during this period and have been shown to have individual and interactive effects on social competence in the preschool years (Diener & Kim, 2004; Eisenberg & Fabes, 1992; Eisenberg et al., 1993).

Why do we find negative effects for the 1-year-olds particularly for the positive social behavior measure, as compared to our assessments of achievement or problem behavior? First, it is notable that the NICHD Study of Early Child Care found that similar assessments of children's negative peer interactions and lack of social competence were associated with more hours in center-based care, after the researchers controlled for both the quality of care and parenting practices (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1998; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2001a). Center-based care has also been associated with increases in the levels of the stress hormone cortisol in children (Dettling, Gunnar, & Donzella 1999; Tout, de Haan, Kipp-Campbell, & Gunnar, 1998; Watamura, Donzella, Alwin, & Gunnar, 2003). Consistent with our findings, the effect on cortisol is larger for children in their 2nd and 3rd years of life (1- or 2-year-old children) than for younger or older children, a response that Watamura et al. (2003) argued is best explained by the stress of social interactions (rather than parent separation, for instance, which would more likely affect infants).

Second, we found that treatment group mothers with 1-year-olds reported less parental warmth than control group mothers with children of the same age. Negative changes in parenting engendered by the programs could help explain the decrease in positive behavior among 1-year-olds. There is evidence that positive parent–child interactions are directly related to children's prosocial behavior (Nomaguchi, 2006) and that less sensitive parenting can interact with child care settings to negatively affect children's social–emotional development (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2001b).

Our finding of positive program impacts on the later school achievement of 2-year-old children is consistent with studies showing positive effects of both maternal employment and center-based child care on the cognitive development of toddlers and preschoolers (e.g., Belsky et al., 2007; Han et al., 2001). The positive impacts did not extend to 3-year-olds in our sample, suggesting again that 2-year-olds may have been particularly well situated developmentally to take advantage of the increased conitive stimulation provided by center-based care. In contrast to younger children, 2-year-olds are better able to verbalize and self-regulate their emotions (Dunn et al., 1987; Grolnick et al., 1996). They have also passed through the most intense period of separation anxiety and are beginning the earliest developments related to understanding the motivations and actions of others (Bolby, 1982; Chandler, Fritz, & Hala 1989).

We faced several data limitations in this study. First and foremost, there was insufficient data to examine infants under 6 months of age, the group for whom maternal separation might be most detrimental. Second, our efforts to identify explanatory pathways were constrained to estimating program impacts on a small number of potential mediators that were measured across the five studies. Our analysis would have been enhanced, for instance, if we had data on not only the type of nonparental child care used by treatment families but also the quantity and quality of that care. Third, our analysis of children's behavior relied on parental reports, which may reflect parents' perceptions of children's behavior rather than children's actual behavior. In fact, other research using these data found that maternal depression was an important predictor of parent-reported behavioral outcomes for children (Crosby, Dowsett, Gennetian, & Huston, 2004). Another concern about parental reports in the context of the present study is that parents may have interpreted questions about positive social behavior differently for children at different stages of social–emotional development. We cannot know the extent to which these measurement issues may have biased our estimates of program impacts, but having a randomly assigned control condition reduces these concerns substantially.

Finally, the results presented in this article cannot speak to the effects of maternal employment that maintains or even decreases family income, a realistic possibility in the current economic and policy context. Not only do the jobs available to welfare recipients generally pay low wages and offer few benefits, but certain welfare policies—including low earnings disregards and extensive sanctions for nonparticipation—make it difficult to increase income by combining earnings and cash assistance. As a result, poor and near poor workers face disproportionately high marginal tax rates (Holt & Romich, 2007).

Despite these limitations, the results of this study provide some of the first information on how young children might be affected by changes in welfare policy. They have salience to current policy and practice because the experiments included key components, such as work requirements and time limits, which were enacted as part of state Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) programs and are still in effect today. Because many states no longer exempt parents with very young children from work requirements, it is critical to understand how children in these families may be affected by changes to maternal employment and family income.

If public policy seeks to improve family economic circumstances sufficiently to positively alter the developmental trajectories of poor children, the primarily neutral results of this study, combined with the findings from other studies showing that increases in income can benefit some age groups of children (Morris et al., 2005) suggest that, at minimum, policies promoting employment should be paired with policies promoting income gain among families. This could be achieved directly with the earned income tax credit or other approaches to supplementing earnings, or indirectly through policies that promote employment stability and wage growth.

The fact that children responded differentially to these changes in family context by age and developmental stage also calls for more education of parents and child care providers about the specific developmental needs of children within the period of early childhood, and perhaps for targeted second-generation interventions for those children at these particularly vulnerable developmental periods. Most of all, this study endorses future research that takes a nuanced view of contextual influences in early childhood and the potentially important transitions within this period that have not been fully explored.

Acknowledgments

This research is part of the Next Generation Project, which examines the effects of welfare and employment policies on children and families. Funding for the Next Generation Project was provided by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the William T. Grant Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, and the Child and Family Well-Being Research Network of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (2 U01 HD30947-07). Our colleague, Greg J. Duncan, was instrumental in the conceptualization of this work. We thank the original sponsors of the studies for permitting reanalyses of the data; Emma Adam, Greg J. Duncan, Lisa Gennetian, JoAnn Hsueh, Aletha Huston, Virginia Knox, and Charles Michalopoulos for thoughtful reviews of drafts of this article; and Chris Rodrigues and Beth Clark-Kauffman for research assistance.

Footnotes

There are exceptions: Greenstein (1995) modeled interactions between measures of advantage and maternal employment and found no evidence of a moderating relationship. Han et al. (2001) found no significant effects of maternal employment during a child's preschool years on Black children but a larger negative relationship between maternal employment in the 1st year of life and later cognition for low-income children than other children.

In total, the data set included 109 observations of children under the age of 6 months at the time of random assignment. Over 80% of those observations were from the SSP 36-month follow-up. Two studies, Minnesota Family Investment Program and New Hope, had no observations for children in this age group.

The variation in sample sizes by outcome measure was the result of data collection strategies, not nonresponse: Measures of child achievement were collected for all children in the family, while measures of child behavior were collected, in nearly all studies, on a single preidentified focal child.

None of the potential mediating variables were randomly assigned to children; family income, maternal employment, child care, parental depression, and parenting styles are all influenced by a variety of factors that were not measured in these studies, including family and parent characteristics, and the outcomes of children themselves. In short, estimates from ordinary least squares models (or comparable structural equation models) that included mediating variables are likely to be biased by omitted variables, simultaneity, or measurement error.

Contributor Information

Heather D. Hill, School of Social Service Administration, University of Chicago

Pamela Morris, MDRC, New York, New York.

References

- Alessandri SM. Effects of maternal work status in single-parent families on children's perception of self and family and school-achievement. Journal of Experimental and Child Psychology. 1992;54:417–433. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. Uncovering gender differences in the effects of early intervention: A reevaluation of the Abecedarian, Perry Preschool, and Early Training Projects. 2005. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Asendorpf JB, Warkentin V, Baudonniere PM. Self-awareness and other-awareness: II. Mirror self-recognition, social contingency awareness, and synchronic imitation. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:313–321. [Google Scholar]

- Baum CL. Does early maternal employment harm child development? An analysis of the potential benefits of leave taking. Journal of Labor Economics. 2003;21:409–448. [Google Scholar]

- Baydar N, Brooks-Gunn J. Effects of maternal employment and child care arrangements in infancy on preschoolers' cognitive and behavioral outcomes: Evidence from the children of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:932–945. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Eggebeen D. Early and extensive maternal employment and young children's socioemotional development—Children of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:1083–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Vandell DL, Burchinal M, Clark-Stewart KA, McCartney K, Owen MT. Are there long-term effects of early child care? Child Development. 2007;78:681–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, Hill J, Waldfogel J. Maternity leave, early maternal employment and child health and development in the US. The Economic Journal. 2005;115:F29–F47. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin G. Encouraging work, reducing poverty: The impact of work incentive programs. New York: MDRC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Blau FD, Grossberg AJ. Maternal labor supply and children's cognitive development. Review of Economics and Statistics. 1992;74:474–481. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom D, Kemple JJ, Morris P, Scrivener S, Verma N, Hendra R. The Family Transition Program: Final report on Florida's initial time-limited welfare program. New York: MDRC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom D, Scrivener S, Michalopoulos C, Morris P, Hendra R, Adams-Ciardullo D, Walter J. Jobs first: Final report on Connecticut's welfare reform initiative. New York: MDRC; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bolby J. Attachment and loss: Vol 1 Attachment. 2nd. New York: Basic Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ, Thompson WW, Kupersmidt JB. Psychosocial adjustment among children experiencing persistent and intermittent family economic hardship. Child Development. 1995;66:1107–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Bos J, Huston A, Granger R, Duncan G, Brock T, McLoyd V. New hope for people with low incomes: Two-year results of a program to reduce poverty and reform welfare. New York: MDRC; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Fritz J, Zahnwaxler C, Ridgeway D. Learning to talk about emotions—A functionalist perspective. Child Development. 1986;57:529–548. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris P. The ecology of developmental processes. In: Damon RW Editor-in-Chief, Lerner M Vol Ed, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol 1. Theoretical models of human development. 5th. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 993–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Han W, Waldfogel J. Maternal employment and child cognitive outcomes in the first three years of life: The NICHD study of early child care. Child Development. 2002;73:1052–1072. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Peisner-Feinberg E, Bryant DM, Clifford R. Children's social and cognitive development and child care quality: Testing for differential associations related to poverty, gender, or ethnicity. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;4:149–165. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell FA, Ramey CT, Pungello E, Sparlin J, Miller-Johnson S. Early childhood education: Young adult outcomes from the Abecedarian Project. Applied Developmental Science. 2002;6:42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Campos JJ, Stenberg CR. Perception, appraisal and emotion: The onset of social referencing. In: Lamb ME, Sherrod LR, editors. Infant social cognition: Empirical and theoretical considerations. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1981. pp. 273–314. [Google Scholar]

- Capizzano J, Adams G. Children in low-income families are less likely to be in center-based child care. Snapshots of America's Families III, No 16. 2004 Retrieved September 9, 2008, from http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/310923_snapshots3_no16.pdf.

- Caughy MO, DiPietro JA, Stobino M. Day-care participation as a protective factor in the cognitive development of low-income children. Child Development. 1994;65:457–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler M, Fritz AS, Hala S. Small-scall deceit: Deception as a marker of two-, three-, and four-year-olds' early theories of mind. Child Development. 1989;60:1263–1277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale PL, Moffitt RA, Lohman BJ, Cherlin AJ, Coley RL, Pittman LD, et al. Mothers' transitions from welfare to work and the well-being of preschoolers and adolescents. Science. 2003 March 7;299:1548–1552. doi: 10.1126/science.1076921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;122:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development. 1992;63:526–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]