Abstract

AIM: To explore the value of fecal lactoferrin in predicting and monitoring the clinical severity of infectious diarrhea.

METHODS: Patients with acute infectious diarrhea ranging from 3 mo to 10 years in age were enrolled, and one to three stool samples from each subject were collected. Certain parameters, including white blood cells /differential count, C-reactive protein, fecal mucus, fecal pus cells, duration of fever, vomiting, diarrhea and severity (indicated by Clark and Vesikari scores), were recorded and analyzed. Fecal lactoferrin was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and compared in different pathogen and disease activity. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were also used for analysis.

RESULTS: Data included 226 evaluations for 117 individuals across three different time points. Fecal lactoferrin was higher in patients with Salmonella (11.17 μg/g ± 2.73 μg/g) or Campylobacter (10.32 μg/g ± 2.94 μg/g) infections and lower in patients with rotavirus (2.82 μg/g ± 1.27 μg/g) or norovirus (3.16 μg/g ± 1.18 μg/g) infections. Concentrations of fecal lactoferrin were significantly elevated in patients with severe (11.32 μg/g ± 3.29 μg/g) or moderate (3.77 μg/g ± 2.08 μg/g) disease activity compared with subjects with mild (1.51 μg/g ± 1.36 μg/g) disease activity (P < 0.05). GEE analysis suggests that this marker could be used to monitor the severity and course of gastrointestinal infections and may provide information for disease management.

CONCLUSION: Fecal lactoferrin increased during bacterial infection and with greater disease severity and may be a good marker for predicting and monitoring intestinal inflammation in children with infectious diarrhea.

Keywords: Lactoferrin, Diarrhea, Generalized estimating equations, Vesikari scores, Clark scores

INTRODUCTION

Infectious diarrhea caused by pathogens may induce gastroenteritis, bloody stool, or severe intraabdominal infections, which spreads disease, especially among infant and child populations, and increases the economic burden. Viral infection is a leading cause of diarrhea among children in developed and developing countries. Moreover, several bacterial pathogens, including Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., and Shigella spp., can cause invasive diarrhea. These pathogens have the capacity to invade the mucosa of the distal small intestine and colon, stimulate local and systemic inflammatory responses, and may sometimes cause hemorrhaging and ulceration of the mucosa. Although acute infectious diarrhea is a common clinical disease in children, few reliable and noninvasive diagnostic tools have been used as biological markers in patients with acute infectious diarrhea or persistent digestive symptoms.

Lactoferrin, an 80 kDa iron-binding glycoprotein produced by many exocrine glands, is a major whey protein with a major constituent in the secondary granules of neutrophilic leukocytes. Lactoferrin displays diverse biological activities, ranging from the activation of innate immunity[1,2], microbicidal effects[3], and anti-cancer cell responses[4]. Exposure of host cells to lactoferrin may modulate subsequent cellular functions, such as cytokine gene activation[5], cytotoxicity[6], and T cell[7] or B cell[8] maturation. Lactoferrin may affect innate immunity by stimulating macrophages through interaction with toll-like receptor pathways[2]. Because diarrheal illnesses are extremely common in communities and hospitals throughout the world, a noninvasive inflammatory marker may be helpful for disease management. The presence of lactoferrin in bodily fluids, including intestinal lumen, is proportional to the flux of neutrophils, and its assessment can provide a reliable biomarker for inflammation. Neutrophils have been shown to be involved in the perpetuation of inflammation in the gut in acute infections caused by Shigella and Salmonella and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[9-11]. Guerrant et al[12] confirmed increased fecal lactoferrin in 96% (25/26) of samples from patients with shigellosis and concluded that fecal lactoferrin was a useful marker for fecal leukocytes.

Few scales are available for evaluating gastroenteritis disease severity. The most commonly used scoring scales are the Vesikari 20-point scale, in which an episode of gastroenteritis with a score ≥ 11 is considered severe[13] (≥ 11 moderate, ≥ 16 severe), and the Clark 24-point scale, in which an episode of gastroenteritis with a score ≥ 16 is considered severe[14]. Our present prospective study was conducted to explore the role of fecal lactoferrin in gastrointestinal infection, including (1) predicting bacterial or viral infection; (2) ascertaining the extent to which values may be associated with the severity of gastroenteritis in the above scales; and (3) monitoring the se-verity and course of gastrointestinal infection, which may provide information for disease management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective study enrolled and analyzed children being treated in Chang Gung Children’s Hospital located in Northern Taiwan. All subjects provided written informed consent, and three fecal samples were collected from each subject.

Enrollment was conducted between September 2008 and May 2010. Diarrhea was defined as three or more outputs of loose or liquid stools per day. Inclusion criteria were 3 mo to 10 years of age and hospitalization with infectious diarrhea. Exclusion criteria were immunodeficiency and history of IBD or gastrointestinal tract surgery. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all eligible children. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Upon entering the study, hospitalized patients received treatment consisting of intravenous fluid and oral rice water or half-strength formula. The severity of diarrhea was evaluated according to the following parameters: volume of stools, fecal consistency and frequency. Other clinical symptoms, including fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, daily intake, and appetite, were also assessed. All participants underwent first-step hematology and biochemistry tests [including blood cell counts, serum C-reactive protein (CRP), and electrolytes] as well as fecal pus cell and mucus analysis. Disease severity was recorded using the severity scoring methods of the Vesikari 20-point scale and Clark 24-point scale. In the Vesikari 20-point scale, an episode of gastroenteritis with a score ≥ 11 is considered moderate or severe (< 11 mild, ≥ 11 moderate, ≥ 16 severe),[5] and in the Clark 24-point scale, an episode of gastroenteritis with a score ≥ 16 is considered severe. Fecal samples of some patients were collected at three different time points, including the initial stage of infectious diarrhea, 3-5 d later and 7-10 d later. Series follow-ups of fecal lactoferrin were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Their control group comprised 15 children (mean age, 3.7 years; range, 1-10 years) without diarrhea. We compared and analyzed the levels of fecal lactoferrin collected from the different patients at the same time point.

Identifying pathogens

To assess the etiology of infectious diarrhea, fecal specimens were collected to detect Salmonella, Shigella or Campylobacter colonies on specifically prepared agar plates. The fecal specimens were also sent for evaluating rotavirus antigen levels by ELISA and norovirus RNA by real-time polymerase chain reaction.

Lactoferrin assay

The stool samples were prepared and analyzed for lactoferrin according to the manufacturer’s instructions (AssayMax Human Lactoferrin ELISA Kit, St. Charles, MO, United States). This assay employs a quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique that measures lactoferrin in 4 h. A polyclonal antibody specific for lactoferrin was pre-coated onto a microplate. Lactoferrin standards and samples were sandwiched by the immobilized antibody and a biotinylated polyclonal antibody specific for lactoferrin recognized by a streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate. Absorbance was read at A450 nm. Lactoferrin was expressed as μg/g of feces.

Statistical analysis

Simple univariate correlation coefficients (Spearman rank correlation) were calculated using baseline data only. Independent associations between the variables of interest were investigated by generalized estimating equations (GEE). GEE is a regression technique that allows the investigation of longitudinal data while adjusting for within-patient correlations. GEE requires a predefined working correlation structure for the dependent variable (lactoferrin), and based on first level and follow-up data, an exchangeable correlation structure was chosen here. The GEE approach was developed to correct for repeated outcomes within the same subject[15]. When using data from more than two time points, the GEE analysis was employed for longitudinal analysis (associations).

A univariate comparison between groups was performed with a t test for repeated measures, and the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used with categorical data. Analyses were performed on the intention-to-treat population. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant, and the statistical tests were two-tailed. The GraphPad Software Prism 3.03 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, United States) and SPSS Software, version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States), were used for the statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Description of samples

A total of 154 participants were screened between September 2008 and May 2010. From that cohort, 37 patients were excluded from further study because no definite pathogen was identified from the stool examination. Among the individuals included in the study, rotavirus infection was diagnosed in 41 patients, and norovirus infection was diagnosed in 28 patients. In addition, Salmonella infection was diagnosed in 31 patients and Campylobacter infection in 17 patients. Demographic details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Gender | |

| Female | 52 |

| Male | 65 |

| Age (mean), yr | 3.23 (3 mo-10 yr) |

| Pathogen identified | |

| Rotavirus | 41 |

| Norovirus | 28 |

| Salmonella | 31 |

| Campylobacter | 17 |

| Disease severity (Vesikari scoring scale) | |

| Mild | 42 |

| Moderate | 50 |

| Severe | 25 |

| Duration of diarrhea (median), h | 73.8 (14-169) |

| Vomiting, (d) | 2.1 (0-5) |

| Fever, (d) | 2.9 (0-7) |

| WBC counts (106/L) | 12 658 ± 2364 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 34.7 ± 22.1 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL, n = 117) | 11.6 (8.2-15.3) |

| Platelets (109/L, n = 117) | 232 (134-585) |

Range in brackets. WBC: White blood cells; CRP: C-reactive protein.

The data include a total of 226 evaluations for 117 individuals across three different time points. The pattern of assessment was as follows: 43 subjects (36.9%) had three assessments, 23 (19.6%) had two assessments, and 51 (43.5%) had one assessment. The mean age of the subjects was 3.23 years (SD 2.15, range 3 m/o-10 y/o), and 65 (55.5%) were male.

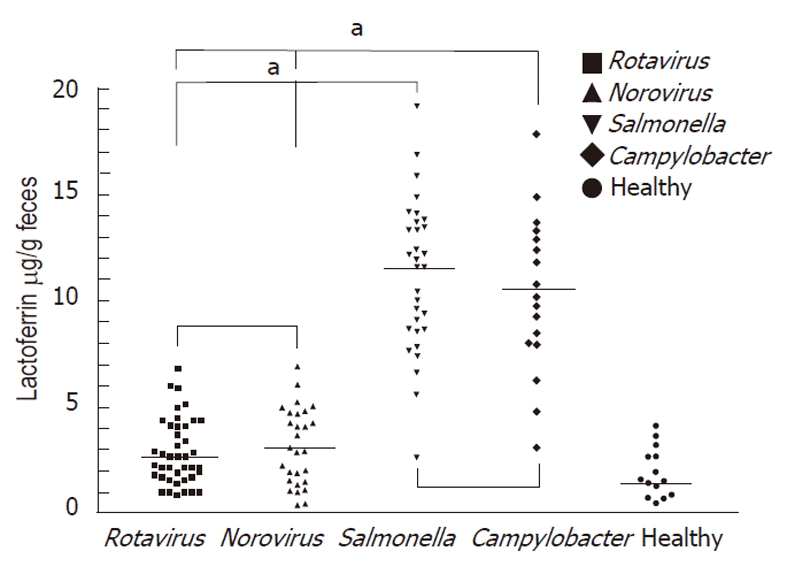

Fecal lactoferrin

The mean ± SD of the fecal lactoferrin concentration was 11.17 μg/g ± 2.73 μg/g in patients with Salmonella infections, 10.32 μg/g ± 2.94 μg/g in patients with Campylobacter infections, 2.82 μg/g ± 1.27 μg/g in patients with rotavirus infections and 3.16 μg/g ± 1.18 μg/g in patients with norovirus infections (Figure 1). Concentrations of each fecal marker for patients with either form of bacterial infection were significantly elevated compared with those of virus-infected patients. The P values for lactoferrin were < 0.05. No statistical differences were observed in fecal lactoferrin concentrations between the clinically confirmed Salmonella and Campylobacter infections. The P values for lactoferrin was 0.71.

Figure 1.

Grouped samples of fecal lactoferrin (μg/ g feces) in healthy children and children with gastroenteritis caused by different pathogens, including rotavirus, norovirus, Salmonella and Campylobacter infection. The mean level of fecal lactoferrin was higher in patients with Salmonella or Campylobacter infections but lower in patients with rotavirus or norovirus infections. Horizontal line: Mean; aP < 0.05.

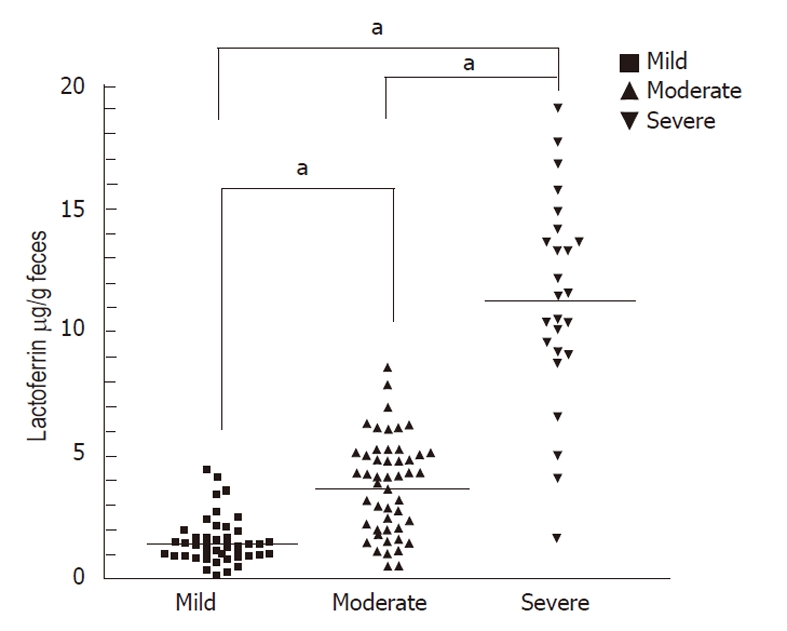

The mean ± SD of fecal lactoferrin concentration was 11.32 μg/g ± 3.29 μg/g in patients with severe disease activity (Vesikari score ≥ 16, Table 2), 3.77 μg/g ± 2.08 μg/g in patients with moderate disease activity (Vesikari score ≥ 11) and 1.51 μg/g ± 1.36 μg/g in patients with mild disease activity (Vesikari score < 11, Figure 2). Concentrations of each fecal marker for patients with either form (viral or bacterial) of severe or moderate disease activity were significantly elevated compared with those of mild disease activity. The P values for lactoferrin were < 0.05.

Table 2.

The Vesikari and Clark severity scoring scales for the evaluation of gastroenteritis in children

| Severity scoring scales | Point value | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Vesikari[5] | |||

| Duration of diarrhea (d) | 1-4 | 5 | ≥ 6 |

| Maximum number of diarrhea stools/24 h | 1-3 | 4-5 | ≥ 6 |

| Duration of vomiting (d) | 1 | 2 | ≥ 3 |

| Maximum number of vomiting episodes/24 h | 1 | 2-4 | ≥ 5 |

| Temperature (°C) | 37.1-38.4 | 38.5-38.9 | ≥ 39.0 |

| Dehydration | - | Mild | Moderate to severe |

| Treatment | Rehydration | Hospitalization | - |

| Clark[6] | |||

| Diarrhea | |||

| Number of stools/d | 2-4 | 5-7 | ≥ 8 |

| Duration in days | 1-4 | 5-7 | ≥ 8 |

| Vomiting | |||

| Number of emeses/d | 1-3 | 4-6 | ≥ 7 |

| Duration in days | 2 | 3-5 | ≥ 6 |

| Rectal temperature | |||

| Temperature (°C) | 38.1-38.2 | 38.3-38.7 | ≥ 38.8 |

| Duration in days | 1-2 | 3-4 | ≥ 5 |

| Behavioral symptoms/signs | |||

| Description | Irritable/less playful | Lethargic/listless | Seizure |

| Duration in days | 1-2 | 3-4 | ≥ 5 |

Figure 2.

Fecal lactoferrin level (μg/ g feces) in children with mild , moderate or severe disease activity according to the Vesikari score (< 11 mild, ≥ 11 moderate, ≥ 16 severe). Levels of fecal lactoferrin were elevated in moderate and severe disease activities. Horizontal line: Mean; aP < 0.05.

Univariate linear regression analysis

Certain parameters associated with the level of fecal lactoferrin, including white blood cells/differential count, C-reactive protein, fecal mucus, fecal pus cells, duration of fever, vomiting, diarrhea and severity (as indicated by Clark and Vesikari scores), were recorded and analyzed. To determine the correlation between these parameters and fecal inflammatory markers, we performed a univariate linear regression analysis.

The univariate linear regression analysis revealed that the Vesikari score, Clark score, fecal pus cells, CRP, vomiting and dehydration were all correlated with lactoferrin level (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate linear regression outcome: Lactoferrin (y = α + βx)

| β | Standard error | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| WBC | -0.05 | 0.10 | -0.25 | 0.14 | 0.581 |

| Segment | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.05 | 0.05 | 0.941 |

| Band | 0.47 | 0.27 | -0.07 | 1.01 | 0.089 |

| CRP | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.043a |

| Fecal pus cell | |||||

| None | 0.00 | ||||

| Present | 0.38 | 1.55 | -2.74 | 3.49 | 0.809 |

| Fecal occult blood | |||||

| None | 0.00 | ||||

| Present | 1.71 | 1.22 | -0.73 | 4.15 | 0.165 |

| Fecal mucus | |||||

| None | 0.00 | ||||

| Positive | -2.21 | 1.46 | -5.14 | 0.71 | 0.135 |

| Vesikari scoring scale | |||||

| Non-severe < 11 | 0.00 | ||||

| Moderate ≥ 11 | 2.76 | -1.50 | 7.02 | 0.191 | |

| Severe ≥ 16 | 2.81 | 1.13 | 0.56 | 5.07 | 0.015a |

| Clark scoring scale | |||||

| Non-severe < 16 | 0.00 | ||||

| Severe ≥ 16 | 3.13 | 1.10 | 0.93 | 5.32 | 0.006a |

| Body temperature | 0.29 | 0.30 | -0.31 | 0.89 | 0.341 |

| Abdominal pain | 0.88 | 0.63 | -0.39 | 2.15 | 0.169 |

| Abdominal distension | -0.30 | 1.01 | -2.32 | 1.71 | 0.764 |

| Dehydration | 3.13 | 1.38 | 0.37 | 5.89 | 0.027a |

| Oral intake | 1.13 | 1.23 | -1.33 | 3.59 | 0.362 |

| Activity | 1.13 | 1.00 | -0.87 | 3.13 | 0.262 |

| Fever day | 0.09 | 0.28 | -0.46 | 0.65 | 0.739 |

| Diarrhea day | 0.41 | 0.29 | -0.60 | 1.41 | 0.423 |

| Vomiting day | -0.99 | 0.53 | -1.93 | -0.04 | 0.041a |

P < 0.05. WBC: White blood cells; Band: Band form neutrophil; CRP: C-reactive protein.

GEE analysis results

Table 4 reveals the results of the multivariate analysis of the predictive value of fecal lactoferrin with time variations. Subjects with higher Vesikari severity scores had higher fecal lactoferrin levels initially (when time = 0), and the levels of fecal lactoferrin may have decreased when followed-up at different time points (when time > 0).

Table 4.

Generalized estimating equations analysis for series follow-up of fecal lactoferrin

| Parameter | Estimate | Standarderror | 95% confidence interval | P value | |

| Clark score | |||||

| Intercept | 5.1523 | 0.7490 | 3.6843 | 6.6202 | < 0.0001a |

| Clark score | 2.0393 | 1.7397 | -1.3704 | 5.4489 | 0.2411 |

| Time | -0.3729 | 0.2530 | -0.8688 | 0.123 | 0.1405 |

| Time x Clark | 0.5826 | 0.8342 | -1.0525 | 2.2177 | 0.485 |

| Vesikari score | |||||

| Intercept | 3.9289 | 0.8437 | 2.2752 | 5.5825 | < 0.0001a |

| Vesikari score | 3.2257 | 1.3018 | 0.6741 | 5.7773 | 0.0132a |

| Time | -0.1835 | 0.2715 | -0.7157 | 0.3487 | 0.4992 |

| Time x Vesikari | -0.1575 | 0.5222 | -1.1811 | 0.8660 | 0.0429a |

| Band (band form neutrophil) | |||||

| Intercept | 3.6654 | 1.0750 | 1.5585 | 5.7723 | 0.0007a |

| Band | 1.9759 | 0.6951 | 0.6135 | 3.3383 | 0.0045a |

| Time | 1.6270 | 0.8206 | 0.0186 | 3.2354 | 0.0474a |

| Band x time | -1.5261 | 0.4677 | -2.4428 | -0.6094 | 0.0011a |

P < 0.05.

(Lactoferrin = 3.9289 + 3.2257 × Vesikari score - 0.1835 × time - 0.1575 × time × Vesikari score)

However, there was no significant relationship between fecal lactoferrin and the Clark score with time variations. On the contrary, subjects with higher band form (%) had higher fecal lactoferrin levels initially (when time = 0), and the levels of fecal lactoferrin may have decreased when followed-up at different time points (when time > 0).

(Lactoferrin = 3.6654 + 1.9759 × Band + 1.627 × time - 1.5261 × Band × time)

DISCUSSION

An intense intestinal infection involves intense infiltration of neutrophils, macrophages, mast cells, lymphocytes, natural killer cells, other inflammatory cells in the epithelial lining and the lamina propria of the colonic mucosa[16]. Cells in the innate immune system secrete various enzymes and metabolites, including myeloperoxidase and lactoferrin, produced by activated neutrophils. Lactoferrin is found mainly in the oral cavity and intestinal tract where it can come into direct contact with pathogens, such as viruses and bacteria. The noninvasive fecal marker lactoferrin may prove useful in screening for inflammation in patients with abdominal pain and diarrhea[17]. Our study demonstrates the usefulness of fecal lactoferrin for detecting colonic inflammation in children with gastrointestinal symptoms, such as enteritis or enterocolitis.

The most significant function of lactoferrin in mucosal defense is its antimicrobial activity. Lactoferrin can also amplify the actions of lysozyme and secretory immunoglobulin A[18]. In vitro studies have shown lactoferrin’s bactericidal effects on V. cholerae, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar mutants, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Candida albicans[19]. Thus, increased stool levels of lactoferrin in acute shigellosis may suggest increased degranulation of neutrophils upon stimulation that may promote the killing of Shigella in the colonic mucosa. Interaction of lactoferrin with immune system cells induces a regulated release of cytokines, such as interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha[19], which has also been observed during acute Shigella infection in adults[20,21] and children.

Fecal lactoferrin has been reported as a promising biomarker in active Crohn’s disease[22] and ulcerative colitis[23], requiring the exclusion of patients enrolled with a history of the above IBDs. Indeed, in patients without known IBDs suspected of having a bacterial diarrheal illness, fecal lactoferrin may be useful in evaluating bacterial gastrointestinal infections in which antimicrobial therapy may be prescribed (e.g., Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, and pathogenic Escherichia coli spp.) and aid in following the inflammatory activity of bacterial infection. Previous study has suggested that fecal lactoferrin could serve as a screening tool for deciding when to perform a stool culture[24]. Fifty-five patients were enrolled in the Choi et al[24] study, and the researchers reported that fecal lactoferrin was higher in invasive bacterial pathogens and might greatly enhance a cost-effective approach for evaluating infectious diarrhea[24]. Fecal lactoferrin could be a more sensitive test than fecal leukocytes for evaluating patients with acute diarrhea. Scerpella et al[25] reported that 94% of travelers with invasive pathogens had positive fecal lactoferrin, while only 69% had fecal leukocytes. The other study has also found that fecal lactoferrin was better than methylene blue for detecting invasive pathogens[26]. According to our study, the fecal lactoferrin level is higher in bacterial gastrointestinal infections, such as Salmonella and Campylobacter, but lower in patients with rotavirus or norovirus infections. The above results are similar to the findings of Choi et al[24] (higher fecal lactoferrin in Salmonella, Campylobacter and Shigella infections but lower in rotavirus infections).

In some meta-analyses of the sensitivity and specificity of different markers of intestinal inflammation associated with invasive pathogens (e.g., fecal leukocytes, occult blood in stool, and fecal lactoferrin), fecal lactoferrin was recommended as having the best diagnostic accuracy[27-29].In enteroaggregative Escherichia coli infectious diarrhea, mucosal inflammation included heavy mucus formation, intimate cell adherence, and secretion of toxins, and the common finding was higher fecal lactoferrin, which suggests a diffuse colonic inflammatory process[30-31]. Our study has demonstrated that fecal lactoferrin is higher in infections caused by Salmonella and Campylobacter and in moderate or severe disease severity.

In our study, the data include 226 evaluations for 117 individuals across three different time points. Concentrations of fecal lactoferrin were significantly elevated in patients with severe or moderate disease activity compared with those with mild disease activity (P <0.05 for each marker). Univariate linear regression analysis revealed that the Vesikari and Clark scores, fecal pus cells, CRP, vomiting and dehydration were all correlated with the lactoferrin level. The parameters of the Vesikari and Clark scores included body temperature, severity of dehydration, and the number of instances and duration of diarrhea and vomiting. Fecal pus cells are usually positive in bacterial infection. Increased CRP may be related to intestinal mucosal inflammation caused by pathogens. Taken together, fecal lactoferrin might correlate with disease activity, which may include the number of instances and duration of diarrhea or vomiting, severity of fever or dehydration, fecal pus cells and CRP.

GEE is a regression technique that allows the investigation of longitudinal data and corrects for the repeated outcomes within the same subject. GEE requires a predefined working correlation structure for the dependent variable (lactoferrin) and is based on first level and follow-up data. In our study, we found that fecal lactoferrin on the first evaluation and follow-up levels were highly associated with Vesikari scores. The above results indicate that fecal lactoferrin may be useful in monitoring the severity of infectious diarrhea during the course of the disease and may provide information for the management of gastrointestinal infection. In addition, fecal lactoferrin levels at the first evaluation and at follow-up were also associated with the band-form percentile. This result suggests that fecal lactoferrin may play a role in monitoring the disease activity and providing guidance for treating infectious diarrhea. According to our study, the measurement of fecal lactoferrin may be a useful noninvasive test for evaluating intestinal infectious or inflammatory situations. For children with persistent diarrhea or recurrent digestive symptoms after one episode of gastrointestinal infection, fecal lactoferrin could be a helpful tool for providing treatment and management information for physicians.

In conclusion, the non-invasive marker fecal lactoferrin was able to predict bacterial or viral infection, and the relative values may be associated with the severity of gastroenteritis, corresponding to Vesikari and Clark scores. Furthermore, fecal lactoferrin may be useful in monitoring the severity and course of gastrointestinal infections, which may provide information for disease management and follow-up.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Shao-Yu Lin for assistance with the statistical analysis.

COMMENTS

Background

This study provides increasing evidence that acute gastrointestinal infection is a common clinical disease in children. Few reliable, noninvasive and painless diagnostic tools have been used as biological markers in patients with acute gastroenteritis.

Research frontiers

How to predict the infectious pathogens (virus or bacteria) that caused acute diarrhea has not been fully clarified. The use of fecal leukocytes, pus cells and serum C-reactive protein has been attempted but was not fully effective. Fecal lactoferrin could be involved in the inflammation caused by the intestinal infectious pathogen. We attempt to investigate a useful noninvasive fecal marker for predicting and monitoring intestinal inflammation in children with infectious diarrhea.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The study design measures the level of fecal lactoferrin during acute infectious diarrhea. The authors also investigated the clinical information and certain parameters of patients, as well as used univariate linear regression analysis and generalized estimating equations to (1) predict bacterial or viral infection; (2) ascertain the extent to which values may be associated with the severity of gastroenteritis; and (3) monitor the severity and course of gastrointestinal infection, which may provide information for disease management.

Applications

This study found that fecal lactoferrin is higher in patients with Salmonella infection or Campylobacter infections but lower in patients with rotavirus infection or norovirus infections. Fecal lactoferrin increased during bacterial infection and with greater disease severity and may be a good marker for predicting and monitoring intestinal inflammation in children with infectious diarrhea.

Peer review

The study by Chen and colleagues presents the value of using fecal lactoferrin to predict and monitor the clinical severity of infectious diarrhea. The study is well planned, includes a robust sample size, is well controlled and the results are clearly interpretable. Perhaps, one benefit, which they argue for the approach in using fecal lactoferrin is that it allows for diagnosis and monitoring without using invasive approaches.

Footnotes

Supported by Chang Gung Memorial Hospital research project grants CMRPG470051-470052

Peer reviewer: Victor E Reyes, PhD, Professor, Departments of Pediatrics and Microbiology and Immunology, Director, GI Immunology Core, Texas Gulf Coast Digestive Diseases Center, Technical Director, Child Health Research Center, University of Texas Medical Branch, 301 University Blvd., Children’s Hospital, Galveston, TX 77555-0366, United States

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Rutherford A E- Editor Xiong L

References

- 1.Miyauchi H, Hashimoto S, Nakajima M, Shinoda I, Fukuwatari Y, Hayasawa H. Bovine lactoferrin stimulates the phagocytic activity of human neutrophils: identification of its active domain. Cell Immunol. 1998;187:34–37. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1997.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curran CS, Demick KP, Mansfield JM. Lactoferrin activates macrophages via TLR4-dependent and -independent signaling pathways. Cell Immunol. 2006;242:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellison RT. The effects of lactoferrin on gram-negative bacteria. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1994;357:71–90. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2548-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damiens E, El Yazidi I, Mazurier J, Duthille I, Spik G, Boilly-Marer Y. Lactoferrin inhibits G1 cyclin-dependent kinases during growth arrest of human breast carcinoma cells. J Cell Biochem. 1999;74:486–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crouch SP, Slater KJ, Fletcher J. Regulation of cytokine release from mononuclear cells by the iron-binding protein lactoferrin. Blood. 1992;80:235–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shau H, Kim A, Golub SH. Modulation of natural killer and lymphokine-activated killer cell cytotoxicity by lactoferrin. J Leukoc Biol. 1992;51:343–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhennin-Duthille I, Masson M, Damiens E, Fillebeen C, Spik G, Mazurier J. Lactoferrin upregulates the expression of CD4 antigen through the stimulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase in the human lymphoblastic T Jurkat cell line. J Cell Biochem. 2000;79:583–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimecki M, Mazurier J, Spik G, Kapp JA. Human lactoferrin induces phenotypic and functional changes in murine splenic B cells. Immunology. 1995;86:122–127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conlan JW, North RJ. Early pathogenesis of infection in the liver with the facultative intracellular bacteria Listeria monocytogenes, Francisella tularensis, and Salmonella typhimurium involves lysis of infected hepatocytes by leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1992;60:5164–5171. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.5164-5171.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perdomo JJ, Gounon P, Sansonetti PJ. Polymorphonuclear leukocyte transmigration promotes invasion of colonic epithelial monolayer by Shigella flexneri. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:633–643. doi: 10.1172/JCI117015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugi K, Saitoh O, Hirata I, Katsu K. Fecal lactoferrin as a marker for disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease: comparison with other neutrophil-derived proteins. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:927–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guerrant RL, Araujo V, Soares E, Kotloff K, Lima AA, Cooper WH, Lee AG. Measurement of fecal lactoferrin as a marker of fecal leukocytes. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1238–1242. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.5.1238-1242.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruuska T, Vesikari T. Rotavirus disease in Finnish children: use of numerical scores for clinical severity of diarrhoeal episodes. Scand J Infect Dis. 1990;22:259–267. doi: 10.3109/00365549009027046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark HF, Borian FE, Bell LM, Modesto K, Gouvea V, Plotkin SA. Protective effect of WC3 vaccine against rotavirus diarrhea in infants during a predominantly serotype 1 rotavirus season. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:570–587. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.3.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardin JW, Hilbe JM. Generalized estimating equations. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pulimood AB, Mathan MM, Mathan VI. Quantitative and ultrastructural analysis of rectal mucosal mast cells in acute infectious diarrhea. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2111–2116. doi: 10.1023/a:1018875718392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kane SV, Sandborn WJ, Rufo PA, Zholudev A, Boone J, Lyerly D, Camilleri M, Hanauer SB. Fecal lactoferrin is a sensitive and specific marker in identifying intestinal inflammation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1309–1314. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levay PF, Viljoen M. Lactoferrin: a general review. Haematologica. 1995;80:252–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pruitt KM, Rahemtulla F, Mønsson-Rahemtulla B. Innate humoral factors. In: Ogra PL, Mestecky J, Lamm ME, Strober W, McGhee JR, et al., editors. Handbook of mucosal immunology. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc; 1994. pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raqib R, Wretlind B, Andersson J, Lindberg AA. Cytokine secretion in acute shigellosis is correlated to disease activity and directed more to stool than to plasma. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:376–384. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raqib R, Lindberg AA, Wretlind B, Bardhan PK, Andersson U, Andersson J. Persistence of local cytokine production in shigellosis in acute and convalescent stages. Infect Immun. 1995;63:289–296. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.289-296.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfefferkorn MD, Boone JH, Nguyen JT, Juliar BE, Davis MA, Parker KK. Utility of fecal lactoferrin in identifying Crohn disease activity in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:425–428. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181d67e8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masoodi I, Kochhar R, Dutta U, Vaishnavi C, Prasad KK, Vaiphei K, Kaur S, Singh K. Fecal lactoferrin, myeloperoxidase and serum C-reactive are effective biomarkers in the assessment of disease activity and severity in patients with idiopathic ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1768–1774. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi SW, Park CH, Silva TM, Zaenker EI, Guerrant RL. To culture or not to culture: fecal lactoferrin screening for inflammatory bacterial diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:928–932. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.928-932.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evaluation of a New Latex Agglutination Test for Fecal Lactoferrin in Travelers' Diarrhea. J Travel Med. 1994;1:68–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.1994.tb00565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yong WH, Mattia AR, Ferraro MJ. Comparison of fecal lactoferrin latex agglutination assay and methylene blue microscopy for detection of fecal leukocytes in Clostridium difficile-associated disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1360–1361. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1360-1361.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huicho L, Campos M, Rivera J, Guerrant RL. Fecal screening tests in the approach to acute infectious diarrhea: a scientific overview. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:486–494. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199606000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gotham IJ, Sottolano DL, Hennessy ME, Napoli JP, Dobkins G, Le LH, Burhans RL, Fage BI. An integrated information system for all-hazards health preparedness and response: New York State Health Emergency Response Data System. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13:486–496. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000285202.48588.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayakawa T, Jin CX, Ko SB, Kitagawa M, Ishiguro H. Lactoferrin in gastrointestinal disease. Intern Med. 2009;48:1251–1254. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hicks S, Nataro JP, Knutton S, Phillips AD. Cytotoxic effects of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAggEC) on human intestinal mucosa in vitro. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1996;22:432. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouckenooghe AR, Dupont HL, Jiang ZD, Adachi J, Mathewson JJ, Verenkar MP, Rodrigues S, Steffen R. Markers of enteric inflammation in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli diarrhea in travelers. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:711–713. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]