Abstract

Summary: RNA-Seq is an exciting methodology that leverages the power of high-throughput sequencing to measure RNA transcript counts at an unprecedented accuracy. However, the data generated from this process are extremely large and biologist-friendly tools with which to analyze it are sorely lacking. MultiExperiment Viewer (MeV) is a Java-based desktop application that allows advanced analysis of gene expression data through an intuitive graphical user interface. Here, we report a significant enhancement to MeV that allows analysis of RNA-Seq data with these familiar, powerful tools. We also report the addition to MeV of several RNA-Seq-specific functions, addressing the differences in analysis requirements between this data type and traditional gene expression data. These tools include automatic conversion functions from raw count data to processed RPKM or FPKM values and differential expression detection and functional annotation enrichment detection based on published methods.

Availability: MeV version 4.7 is written in Java and is freely available for download under the terms of the open-source Artistic License version 2.0. The website (http://mev.tm4.org/) hosts a full user manual as well as a short quick-start guide suitable for new users.

Contact: johnq@jimmy.harvard.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

RNA-Seq profiles the transcriptome (the complete set of transcripts in a cell) using high-throughput deep sequencing. This technique compares favorably to previously used methods for gene expression measurement, such as DNA microarrays, because of its higher sensitivity, lower background and ability to detect previously unknown transcripts. However, the base pair level resolution of this sequencing-based method generates volumes of data that are difficult to process and analyze on desktop computers. This massive scale of data output presents a problem for biologists with little access to ‘big iron’ computer resources and the programming skills required to use them.

The first part of this problem, already in large part addressed by the bioinformatics community, is that of processing, storing and retrieving vast amounts of raw sequencing data, quantifying it and mapping it to the genome. Applications such as Bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009), SOAP (Li et al., 2008a), MAQ (Li et al., 2008b) and RMAP (Smith et al., 2008) map the reads from RNA-Seq to the reference genome or assemble them into contiguous sequences. These methods are rapidly becoming standardized; core facilities and automated pipelines perform these steps along with an additional summarization step, providing pre-mapped expression data most often in a transcript-by sample matrix format similar to that generated by DNA microarrays.

This compressed format loses information about the sequences of the original transcripts, but provides the basic data that most scientists need to address their experimental questions while avoiding difficulties presented by the identifiability of individuals via patterns of genomic variation (Habegger et al., 2011).

The second challenge is similar to that faced by scientists using early DNA microarrays: the biologists who designed the experiments need easy-to-use tools with which to explore their data. Users of RNA-Seq data need access to robust statistical methods, exploratory data analysis tools and approaches to functional meta-analysis to identify patterns in their data, transcripts that correlate with their experimental phenotypes and the mechanisms at the heart of their experimental systems.

Here, we report the adaptation of the MeV (Saeed et al., 2003, 2006) gene expression analysis tool for this purpose. MeV is a java-based desktop application that wraps an extensive array of clustering, statistical and visualization tools in an easy-to-learn graphical user interface. MeV was downloaded >32 000 times in the past calendar year and the current version builds on nearly 10 years of development. Our work in adapting MeV to RNA-Seq analysis has included extending MeV's data model to work with existing transcriptomic analysis tools and the addition of a suite of published algorithms specifically designed for RNA-Seq data analysis.

2 FEATURES

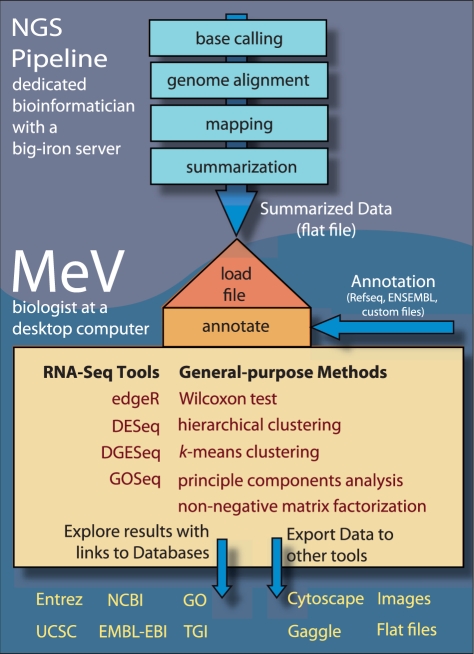

The latest release of MeV has been adapted to load, annotate, visualize and analyze RNA-Seq data. A schematic showing the possible workflow for RNA-Seq analysis using MeV is shown in Figure 1. The most significant changes in MeV's architecture have been adjustments to its data model that allow loading of read counts, normalized transcript expression levels, transcript lengths and read library sizes. The new RNA-Seq file loader supports the import of this type of data from a simple, tab-delimited format, clearly documented in the user manual. In the process, MeV automatically annotates the data, loading transcript/gene level annotation from the UCSC or Ensembl databases. It can load discrete count level data as well as expression data (as RPKM or FPKM values). Raw sequence counts per transcript are converted to RPKM values automatically and vice versa, using the RPKM method described in Mortazavi et al. (2008). The application framework makes it easy to add other data formats as the community develops new standards for RNA-Seq.

Fig. 1.

A potential workflow for RNA-Seq data analysis using MeV.

Once the data have been loaded and annotated, it can be analyzed using both existing tools and new modules that address RNA-Seq-specific issues, such as transcript length and abundance biases. There are three differential expression analysis methods based on the Bioconductor packages DESeq (Anders and Huber, 2010), DGESeq (Wang et al., 2010) and EdgeR (Robinson et al., 2010) that analyze differential expression using RNA-Seq-specific statistics. For the user, the transition from array to sequence data analysis is seamless as these modules are built on the same user interface that has made MeV's methods widely accessible. Since most scientists are interested in understanding the functional differences in gene expression between experimental groups, we also created a module based on GOSeq, a Bioconductor package that tests for enrichment of gene lists (Young et al., 2010). These algorithms allow MeV to account for RNA-Seq-specific data biases, such as transcript length bias in which more reads are mapped to longer transcripts, and selection bias, the overdetection of highly expressed transcripts (Oshlack and Wakefield, 2009).

In addition, users can apply the now standard analysis functions in expression analysis, such as hierarchical clustering, k-means clustering, t-tests, analysis of variance (ANOVA), EASE (the DAVID algorithm, Dennis et al., 2003) and many others. Heatmap displays, gene expression graphs and tabular listings are all included in the standard MeV data displays. Gene-level annotation is linked to appropriate online databases, such as Entrez and Gene Ontology, and can be accessed with simple hyperlinks. Genes of interest can be labeled and compared with one another, and stored as basic gene identifier lists or as tab-delimited files containing expression data for analysis in other applications.

3 CONCLUSIONS

We have publicly released MeV 4.7 with new features allowing the loading and analysis of RNA-Seq data within the framework of existing methods while adding four new RNA-Seq-specific modules based on robust, published algorithms. With these new features, scientists can apply the familiar tools of clustering, differential expression analysis and visualization to an entirely new type of data. These modules are built on the same simple user interface that has made MeV accessible to researchers of all computer literacy levels. Already, the unannounced beta release has been downloaded 2200 times, providing some indication of the perceived need for tools such as MeV within the community.

This release also provides a framework for the further development of RNA-Seq analysis tools, and the easy addition of new R-based modules. The MeV development team looks forward to including additional modules specific to RNA-Seq data analysis as they are developed and published by the community.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the former developers of the MeV and TM4 software projects, as well as the developers of R and Bioconductor.

Funding: National Library of Medicine of the US National Institute of Health (1R01LM008795-01).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Footnotes

†The authors wish it to be known that, in their opinion, the first two authors should be regarded as joint First Authors.

REFERENCES

- Anders S., Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis G., et al. DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habegger L., et al. RSEQtools: a modular framework to analyze RNA-Seq data using compact, anonymized data summaries. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:281–283. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., et al. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., et al. Mapping short DNA sequencing reads and calling variants using mapping quality scores. Genome Res. 2008a;18:1851–1858. doi: 10.1101/gr.078212.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., et al. SOAP: short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics. 2008b;24:713–714. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A., et al. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshlack A., Wakefield M.J. Transcript length bias in RNA-seq data confounds systems biology. Biol. Direct. 2009;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M.D., et al. edgeR: a bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed A.I., et al. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. BioTechniques. 2003;34:374–378. doi: 10.2144/03342mt01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed A.I., et al. TM4 microarray software suite. Methods Enzymol. 2006;411:134–193. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)11009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A.D., et al. Using quality scores and longer reads improves accuracy of Solexa read mapping. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., et al. DEGseq: an R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:136–138. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young M.D., et al. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]