Abstract

How can self-knowledge of personality be improved? What path is the most fruitful source for learning about our true selves? Previous research has noted two main avenues for learning about the self: looking inward (e.g., introspection) and looking outward (e.g., feedback). Although most of the literature on these topics does not directly measure the accuracy of self-perceptions (i.e., self-knowledge), we review these paths and their potential for improving self-knowledge. We come to the conclusion that explicit feedback, a largely unexamined path, is likely a fruitful avenue for learning about one’s own personality. Specifically, we suggest that self-knowledge might be fully realized through the use of explicit feedback from close, knowledgeable others. As such, we conclude that the road to self-knowledge likely cannot be traveled alone but must be traveled with close others who can help shed light on our blind spots.

Keywords: self-knowledge, personality, feedback, introspection

“Surely I ought to know myself better than these indifferent outsiders can know me; nay, better even than my intimate friends, to whom I have never breathed those items of my inward experience which have chiefly shaped my life.

Yet I have often been forced into the reflection that even the acquaintances who are as forgetful of my biography and tenets as they would be if I were a dead philosopher, are probably aware of certain points in me which may not be included in my most active suspicion. We sing an exquisite passage out of tune, and innocently repeat it for the greater pleasure of our hearers.”

–Eliot (1879, p. 6)

Self-knowledge of personality is far from perfect (Vazire and Carlson, 2010, 2011). People sometimes have mistaken views about how they behave (Gosling et al., 1998; Vazire and Mehl, 2008), about their motives (Schultheiss and Brunstein, 2001; Schultheiss, 2008), and about their personality traits (Kolar et al., 1996; Vazire, 2010). As the opening quote from Eliot suggests, there are important aspects of our personalities that we are unaware of.

Why should we be concerned about the difficulty of obtaining self-knowledge? Although there is some controversy about whether it is better to possess accurate or overly positive self-views (Kurt and Paulhus, 2008; Kwan et al., 2008), self-knowledge clearly has its purposes (Dunning et al., 2004). In many real-life situations, the benefits of self-knowledge likely outweigh the costs (e.g., when deciding what career to pursue). Given the value of accurate self-views, an important question for personality science to investigate is: How can self-knowledge of personality be improved?

People typically believe they are the best judges of their own personality (Schoeneman, 1981; Schoeneman et al., 1984; Sedikides and Skowronski, 1995; Pronin et al., 2001; Vazire and Mehl, 2008). Thus, the first step to improving self-knowledge is acknowledging one’s blind spots. However, once a person is open to the idea that they have misconceptions about their own personality, how can they go about fixing them? Following in the footsteps of previous researchers (e.g., Sedikides and Skowronski, 1995; Dunning et al., 2004), we organize the sources of self-knowledge into two broad categories: intrapersonal approaches (e.g., introspection) and interpersonal approaches (e.g., feedback). Below we briefly review these sources as approaches to improving self-knowledge of personality, and make suggestions for future research. We conclude that the road to self-knowledge is likely interpersonal.

Looking Inward: Intrapersonal Routes to Self-Knowledge

Many aspects of our personality are internal. Our patterns of thoughts, feelings, desires, and sensations all occur within our own minds and are not directly observable to others. Furthermore, even our behavior is, in principle, highly accessible to us. No one else has the opportunity to observe everything we do. Thus, it seems natural to presume that reflecting on our pattern of mental states and behaviors should help us learn about our own personality.

Self-focused methods for learning about the self have long been an interest of study in psychology, going back at least to James (1890). Bem’s (1967) self-perception theory suggests that individuals come to know themselves by observing their own behaviors, and Duval and Wicklund’s (1972) objective self-awareness theory similarly posits that self-focused attention allows the self to stand out in one’s consciousness and allows for self-evaluation against some self standard. Although neither theory is specifically about self-knowledge of personality, both point to the potential for introspection and self-observation to improve self-knowledge. The important role given to introspection in these classic theories squares well with the layperson’s view that the self is the best source of information about what a person is like (Pronin et al., 2004; Vazire and Mehl, 2008). However, the empirical evidence supporting self-reflection as a route to self-knowledge is mixed at best.

Introspection

Can we learn about our personalities by reflecting on ourselves? In certain cases, the layperson may be correct to think that introspection is a valid source of self-knowledge (Hixon and Swann, 1993; Sedikides et al., 2007). For example, Sedikides and colleagues found that individuals who had the opportunity to introspect rated themselves less positively than did individuals who did not introspect. Although accuracy was not assessed (so we cannot know if these less positive ratings were more accurate), these findings suggest that introspection may reduce bias, at least for those people who tend to self-enhance. Likewise, Hixon and Swann (1993) found that cognitive load led to increased self-enhancement but that introspection reduced the tendency to self-enhance, suggesting that people with the opportunity to reflect provide less biased self-views. These studies are consistent with other research showing that depleting self-regulatory resources results in more positive self-descriptions (Paulhus and Levitt, 1987; Paulhus et al., 1989; Vohs et al., 2005). Together, these findings suggest that introspection may be useful in reducing certain biases (i.e., self-enhancement), or perhaps simply that self-depletion or cognitive load lead to overly positive self-views.

Other evidence casts doubt on the viability of self-reflection as a route to self-knowledge. Wilson’s work on the effects of analyzing one’s feelings or preferences shows that this type of self-reflection can even impede accuracy (Wilson et al., 1995; Wilson, 2002; Wilson and Gilbert, 2003; Wilson and Dunn, 2004). Similarly, Silvia and Gendolla (2001) have argued that many of the studies purporting to find that introspection leads to greater self-knowledge do not in fact measure accuracy using an objective criterion. Nevertheless, there is some hope for introspection – Schultheiss and Brunstein (1999), for example, found that guided goal-imagery brought people’s explicit motives in line with their implicit motives. More generally, introspection may work when people pay attention to subtle cues (Wilson, 2003; Hofmann and Wilson, 2010), or are educated about the common pitfalls and biases associated with introspection (Pronin and Kugler, 2007).

Self-observation

One of the tools people can use that may improve the effectiveness of self-reflection is paying attention to their own behavior. Much research shows that one of the main obstacles to fruitful self-reflection is the excessive weight people place on their internal thoughts and feelings, at the expense of observing their own behavior (Pronin and Kugler, 2007; Pronin, 2008). However, an obvious problem with self-observation is one’s visual perspective. Individuals are not actually able to look upon themselves from another’s perspective. No matter how much effort is placed on imagining one’s physical image, there is no disputing the fact that there are certain features of the body that are impossible to view firsthand in real time. Furthermore, behaviors simply are not as salient to individuals as are their thoughts and feelings (Malle and Knobe, 1997).

Perhaps a more promising avenue for self-observation is making self-observation literal – that is, showing individuals videos of themselves. Watching a video of one’s interaction from a third-person perspective (as opposed to a video from a first-person perspective or no video at all) seems to improve people’s awareness of their personality, behavior, and the impression they make on others (Cooper and Thompson, 1971; Storms, 1973; Albright and Malloy, 1999). However, despite these promising findings, people rarely have the opportunity to view their behaviors from an actual outside perspective. Furthermore, there is evidence that these effects may not last more than a few days (Vazire et al., 2009).

In conclusion, the evidence for intrapersonal routes to self-knowledge is not encouraging. There are inevitable blind spots in our self-knowledge and the motive for accurate self-assessment is not always predominant. As a tool for acquiring self-knowledge, self-awareness likely cuts both ways. Thanks to our self-awareness, we have the unique ability to reflect on our thoughts, feelings, and desires. However, our self-awareness also burdens us with unique motivational obstacles to objective self-assessment. That is, all kinds of motivational baggage comes into play when people judge themselves that is absent (or less influential) when judging others (John and Robins, 1993; Vazire, 2010). Sadly, these obstacles cannot easily be overcome through introspection or self-observation alone – whatever biases existed before self-reflection are likely to still be there afterward. Nevertheless, all avenues have not been explored, and the inclusion of accuracy criteria in future research may shed further light on the efficacy of self-focused routes to self-knowledge.

Looking Outward: Interpersonal Routes to Self-Knowledge

The idea that we can learn about ourselves from others is as old as the notion of introspection. Festinger’s (1954) social comparison theory was originally a theory about self-knowledge – Festinger believed that people have a drive to evaluate themselves accurately in order to improve their skills and opinions. More recent research shows, however, that accuracy (i.e., self-assessment) is only one among many self-perception motives, in addition to self-enhancement, self-verification, and self-improvement (Swann and Read, 1981; Sedikides and Strube, 1995, 1997; Swann and Pelham, 2002). Given the strength of these other motives, social comparison is often co-opted for the purpose of boosting one’s self-esteem or confirming one’s pre-existing self-views, rather than improving self-knowledge (Wood et al., 1994).

A similarly idealistic theory about self-knowledge is Cooley’s (1902) looking-glass theory. According to this theory, people correctly imagine how others see them, and change their self-views accordingly. Like social comparison theory, this theory gives an important role to other people’s perceptions of the self. However, also like social comparison theory, this theory presumes that people are capable of (and strive for) objective self-evaluation. Unfortunately, people’s perceptions of how others see them are far from perfectly accurate (Carlson et al., 2011a), and when people are aware of such discrepancies, they are not likely to automatically adopt others’ opinions (Carlson et al., 2011b). Given the impediments to achieving self-knowledge by using imagined others (e.g., through social comparison or reflected appraisals), it may be more fruitful to seek information from real others. Perhaps what is needed to improve self-knowledge is not the idea or image of what others think of us, but actual, concrete evidence about what others think of us, and where we stand relative to others.

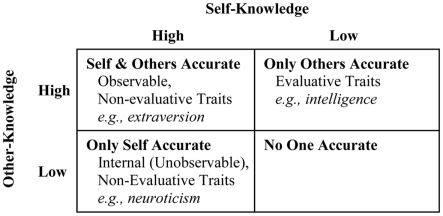

Before putting too much stock in the promise of feedback for improving self-knowledge, we first need to ask whether others have knowledge to impart. That is, do others know things about us that we do not know about ourselves? Vazire’s (2010) self-other knowledge asymmetry (SOKA) model (summarized in Figure 1) proposes that others should know more than the self about aspects of personality that are observable (e.g., dominant, funny) and those that are highly evaluative (e.g., attractive, intelligent). This is supported by a number of studies documenting that these trait attributes, observability and evaluativeness, influence the content and validity of self-ratings (e.g., John and Robins, 1993). Furthermore, a growing number of studies are finding that, when the trait being judged is observable or highly evaluative, close others provide incremental validity over self-ratings, and sometimes outperform the self-ratings outright. For example, close others’ ratings are more accurate than self-ratings at predicting creativity (Vazire, 2010), involuntary discharge from the military (Fiedler et al., 2004), college GPA (Wagerman and Funder, 2007), job performance (Connelly and Ones, 2010), and coronary artery calcification (Smith et al., 2008). Of course, there are also many constructs for which self-ratings are more valid than close others’ ratings – the point is not to claim that one perspective is more accurate than the other overall, but to establish that each perspective has some knowledge that the other does not (Vazire and Carlson, 2011). As Funder’s Realistic Accuracy Model (RAM) suggests, accurate personality judgment is a complicated process in which many steps must be achieved (Funder, 1995, 1999). Collectively, the research reviewed suggests that close others, such as friends, family members, and coworkers, are often able to navigate this process and as a result possess knowledge about a person’s personality that she herself lacks. As such, close others are a potential source of feedback for improving self-knowledge. In the sections that follow, we review the evidence concerning the utility of feedback for improving self-knowledge. We focus on personality feedback, but where appropriate we draw from the (much larger) literature on performance feedback and speculate about how the conclusions from that literature would apply to personality feedback.

Figure 1.

The self-other knowledge asymmetry model, summarized from Vazire (2010).

What counts as feedback? As mentioned above, several theories in social and personality psychology propose that people’s reflected appraisals – how they imagine others see them – influence their self-perceptions. However, this type of “feedback” occurs entirely within the person’s mind, and does not entail any new information that cannot be accessed through introspection or self-reflection. Another common type of feedback is “bogus” feedback, where participants are given information that is supposedly about their personality, but this information is actually fabricated by the researchers and does not necessarily apply to the individual. The point of these studies is usually to examine how people react to positive or negative information about themselves, rather than to increase self-knowledge. Here we define feedback as new, true information about oneself that could not have been accessed through introspection alone. Typically, this comes from other people, though it can sometimes come from formal evaluations or other means. A common example of informal feedback from others involves positive or negative comments from friends. For example, Joe may one day be told by his close friends (who have until now kindly put up with him without saying anything) that he tends to be self-centered, always focusing conversations on himself. How is Joe likely to react to this feedback? Will he change his self-perception to be more in line with reality? Will he change his behavior? Here we review the factors that likely affect the effectiveness of feedback.

When feedback comes from others, it likely matters a great deal who the “other” is. Close others are more accurate in their personality judgments than are less well-acquainted others (Colvin and Funder, 1991; Vazire, 2010). However, level of acquaintance is not the only factor that can influence the validity of perceptions, and hence feedback. Close others often have positive biases about each other, and so may not be objective in their perceptions, especially for evaluative traits. Thus, well-acquainted informants who are not particularly attached to the target may be less biased in their ratings than those who are very attached to or fond of the target (Leising et al., 2010). As such, if people can choose who will be providing the feedback, they are likely to nominate close others who are likely to be biased. From an accuracy standpoint, the ideal source of feedback is someone who knows the target well but has enough distance to be objective. Care must also be taken when evaluating feedback from individuals with an idiosyncratic negative view of a person – this can be inaccurate and quite damaging information. However, if the feedback converges among several trusted, well-acquainted others, it is more likely this reputation is relatively accurate.

Of course, in selecting an informant as a source of feedback, accuracy is not the only consideration. It is also important to take into account whether the target will accept the feedback, and, not surprisingly, feedback given by credible sources is more likely to be accepted (Albright and Levy, 1995; Steelman and Rutkowski, 2004). Furthermore, negative “bogus” personality feedback is more likely to be accepted when it is given from individuals of higher status (Halperin et al., 1976). These findings indicate the importance of considering characteristics of the feedback source and his or her relationship with the recipient when feedback acceptance is the goal.

Whether a person accepts feedback also depends on characteristics of the target herself. People with high self-esteem are generally more positive toward the feedback process (Funderburg and Levy, 1997), and people who have an internal locus of control tend to view feedback more favorably (Funderburg and Levy, 1997; Maurer and Palmer, 1999). In general, individuals with a higher core self-evaluation – that is, high self-ratings on measures of self-esteem, self-efficacy, emotional stability, and internal locus of control – respond more positively to feedback (Bono and Colbert, 2005; Kamer and Annen, 2010). Higher levels of extraversion and openness to experience may also help individuals react more openly to negative feedback (Smither et al., 2005). These individual differences make it apparent that not everyone is open to explicit feedback and to incorporating others’ views into their self-knowledge.

How often does feedback happen in everyday life, outside of business settings and laboratory experiments? We examined this question in a recent class exercise in which samples of 106 and 76 (182 total) undergraduates wrote essays describing a time in which they learned something new about their personalities. The essays were coded separately by seven research assistants who were split across the two samples. These essays were coded for the source (self vs. other) of the new information learned by the student (α = 0.84 and 0.85), and how convinced the student seemed of the new information (on a scale from 1 to 7; α = 0.76 and 0.75). Six separate research assistants (three for each sample) then rated the desirability (α = 0.95 and 0.85) and the observability (α = 0.67 and 0.71) of the new information learned (on a scale from 1 to 9). Consistent with the SOKA model (Vazire, 2010), most students reported learning about relatively observable and evaluative traits, which reflects the blind spots in self-knowledge. The majority of students (63%) reported learning about their personality from others (in contrast to 37% who learned from introspection or self-observation). However, these essays also highlight an obstacle to the utility of feedback in everyday life. Results of the combined samples indicate that (a) individuals tend to learn about less desirable traits from others (M = 3.63) compared to the self (M = 4.87), t(127.19) = −3.53, p = 0.001, and (b) individuals tend to be less convinced of information learned from others (M = 4.65) compared to the self (M = 5.44), t(179.40) = −6.62, p < 0.001.

Given that people not only have some difficulty believing information learned from others, but that they also typically respond less well to negative than positive feedback (Kluger and DeNisi, 1996; Facteau et al., 1998; Brett and Atwater, 2001; Atwater and Brett, 2005), it is crucial that people receiving negative feedback are allowed to process it in the most effective way possible. Although there is some evidence that individuals who receive negative feedback are more motivated to change (Smither et al., 2003; Atwater and Brett, 2005), it is important that recipients are not overwhelmed with negative information (Smither and Walker, 2004). For both negative and positive feedback, allowing for a processing phase helps recipients reap the full benefits of feedback. Although self-improvement does not go hand-in-hand with self-knowledge, the findings that attending multiple feedback workshops (Seifert and Yukl, 2010), discussing feedback with raters (Walker and Smither, 1999; Smither et al., 2004), and writing reflections about one’s feedback (Anseel et al., 2009) improve related work performance suggest that individuals are more responsive to feedback when time and effort are dedicated to processing the information.

Even under the best circumstances, however, some people will be resistant to feedback. As with other routes to self-knowledge, the effectiveness of feedback will depend in part on a person’s goals and motives. Does he want to improve the accuracy of his self-views? Is he defensive and interested in protecting or affirming his existing, biased self-views? Returning to our example of self-centered Joe, he has several options for how to react to his friends’ feedback. Joe could deny the feedback, stating that his friends are wrong; he could accept the feedback as accurate and change his self-views accordingly; or he could feel pressure to change his behavior as a result of the negative feedback, without changing his self-views. All of these choices have their own consequences, the third likely leading to the most positive social and personal outcomes. If Joe either accepts the feedback as accurate or changes his behavior to prove the feedback is inaccurate, these changes could improve the quality of his relationships at work and in his social life, and perhaps even the quality of his physical and psychological health (Dunning et al., 2004).

One uniquely promising aspect of feedback as a route to self-knowledge is that, unlike the intrapersonal routes to self-knowledge, feedback actually gives the person new information to consider. Even if the person does not accept this new information right away, she may store it in memory and come back to it later, perhaps when more evidence presents itself that confirms the original feedback. If a person is confronted with repeated feedback from trusted sources, and if the recipient is appropriately prepared for the information, knowledge may be gained that would have otherwise never been possible through self-guided efforts. In short, the search for self-knowledge likely requires the active involvement of close others to help fill in our blind spots.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Albright L., Malloy T. E. (1999). Self-observation of social behavior and metaperception. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 77, 726–734 10.1037/0022-3514.77.4.726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albright M. D., Levy P. E. (1995). The effects of source and performance rating discrepancy on reactions to multiple raters. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 25, 577–600 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1995.tb01600.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anseel F., Lievens F., Schollaert E. (2009). Reflection as a strategy to enhance task performance after feedback. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 110, 23–35 10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atwater L. E., Brett J. F. (2005). Antecedents and consequences of reactions to developmental 360° feedback. J. Vocat. Behav. 66, 532–548 10.1016/j.jvb.2004.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bem D. J. (1967). Self-perception: an alternative interpretation of cognitive dissonance phenomena. Psychol. Rev. 74, 183–200 10.1037/h0025145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bono J. E., Colbert A. E. (2005). Understanding responses to multi-source feedback: the role of core self-evaluations. Pers. Psychol. 58, 171–203 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00633.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brett J. F., Atwater L. E. (2001). 360° feedback: accuracy, reactions, and perceptions of usefulness. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 930–942 10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson E. N., Vazire S., Furr R. M. (2011a). Meta-insight: do people really know how others see them? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 101, 831–846 10.1037/a0024297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson E. N., Vazire S., Oltmanns T. F. (2011b). You probably think this paper’s about you: narcissists’ perceptions of their personality and reputation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 101, 185–201 10.1037/a0023781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin C., Funder D. C. (1991). Predicting personality and behavior: a boundary on the acquaintanceship effect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 60, 884–894 10.1037/0022-3514.60.6.884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly B. S., Ones D. S. (2010). An other perspective on personality: meta-analytic integration of observers’ accuracy and predictive validity. Psychol. Bull. 136, 1092–1122 10.1037/a0021212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley C. H. (1902). Human Nature and the Social Order. New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons [Google Scholar]

- Cooper E. B., Thompson M. P. (1971). Accuracy of stutterer perceptions following self-observation through video recordings. J. Commun. Disord. 4, 119–125 10.1016/0021-9924(71)90020-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning D., Heath C., Suls J. M. (2004). Flawed self-assessment: implications for health, education, and the workplace. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 5, 69–106 10.1111/j.1529-1006.2004.00018.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval S., Wicklund R. A. (1972). A Theory of Objective Self Awareness. Oxford: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Eliot G. (1879). Impressions of Theophrastus Such. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers; Available at: http://books.google.com/books [Google Scholar]

- Facteau C. L., Facteau J. D., Shoel L. C., Russell J. A., Poteet M. (1998). Reactions of leaders to 360-degree feedback from subordinates and peers. Leadersh. Q. 9, 427–448 10.1016/S1048-9843(98)90010-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 7, 117–140 10.1177/001872675400700204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler E. R., Oltmanns T. F., Turkheimer E. (2004). Traits associated with personality disorders and adjustment to military life: predictive validity of self and peer reports. Mil. Med. 169, 207–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funder D. C. (1995). On the accuracy of personality judgment: a realistic approach. Psychol. Rev. 102, 652–670 10.1037/0033-295X.102.4.652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funder D. C. (1999). Personality Judgment: A Realistic Approach to Person Perception. San Diego, CA: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Funderburg S., Levy P. E. (1997). The influence of individual and contextual variables on 360-degree feedback system attitudes. Group Organ. Manage. 22, 210–235 10.1177/1059601197222005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling S. D., John O. P., Craik K. H., Robins R. W. (1998). Do people know how they behave? Self-reported act frequencies compared with on-line codings by observers. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 1337–1349 10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin K., Snyder C. R., Shenkel R. J., Houston B. (1976). Effects of source status and message favorability on acceptance of personality feedback. J. Appl. Psychol. 61, 85–88 10.1037/0021-9010.61.1.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hixon J., Swann W. B., Jr. (1993). When does introspection bear fruit? Self-reflection, self-insight, and interpersonal choices. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 64, 35–43 10.1037/0022-3514.64.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W., Wilson T. D. (2010). “Consciousness, introspection, and the adaptive unconscious,” in Handbook of Implicit Social Cognition: Measurement, Theory, and Applications, eds Gawronski B., Payne B. K. (New York, NY: Guilford Press; ), 197–215 [Google Scholar]

- James W. (1890). “The consciousness of self,” in The Principles of Psychology, Vol. 1, ed. James W. (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Co; ), 291–401 [Google Scholar]

- John O. P., Robins R. W. (1993). Determinants of interjudge agreement on personality traits: the big five domains, observability, evaluativeness, and the unique perspective of the self. J. Pers. 61, 521–551 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1993.tb00781.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamer B., Annen H. (2010). The role of core self-evaluations in predicting performance appraisal reactions. Swiss J. Psychol. 69, 95–104 10.1024/1421-0185/a000011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger A. N., DeNisi A. (1996). Effects of feedback intervention on performance: a historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychol. Bull. 119, 254–284 10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kolar D. W., Funder D. C., Colvin C. (1996). Comparing the accuracy of personality judgments by the self and knowledgeable others. J. Pers. 64, 311–337 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00513.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurt A., Paulhus D. L. (2008). Moderators of the adaptiveness of self-enhancement: operationalization, motivational domain, adjustment facet, and evaluator. J. Res. Pers. 42, 839–853 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.11.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan V. Y., John O. P., Robins R. W., Kuang L. (2008). Conceptualizing and assessing self-enhancement bias: a componential approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 94, 1062–1077 10.1037/0022-3514.94.6.1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leising D., Erbs J., Fritz U. (2010). The letter of recommendation effect in informant ratings of personality. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 98, 668–682 10.1037/a0018771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malle B. F., Knobe J. (1997). Which behaviors do people explain? A basic actor–observer asymmetry. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 72, 288–304 10.1037/0022-3514.72.2.288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer T. J., Palmer J. K. (1999). Management development intentions following feedback: role of perceived outcomes, social pressures, and control. J. Manage. Dev. 18, 733–751 10.1108/02621719910300784 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus D. L., Graf P., Van Selst M. (1989). Attentional load increases the positivity of self-presentation. Soc. Cogn. 7, 389–400 10.1521/soco.1989.7.4.389 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus D. L., Levitt K. (1987). Desirable responding triggered by affect: automatic egotism? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 52, 245–259 10.1037/0022-3514.52.2.245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pronin E. (2008). How we see ourselves and how we see others. Science 320, 1177–1180 10.1126/science.1154199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronin E., Gilovich T., Ross L. (2004). Objectivity in the eye of the beholder: divergent perceptions of bias in self versus others. Psychol. Rev. 111, 781–799 10.1037/0033-295X.111.3.781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronin E., Kruger J., Savtisky K., Ross L. (2001). You don’t know me, but I know you: the illusion of asymmetric insight. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 81, 639–656 10.1037/0022-3514.81.4.639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronin E., Kugler M. B. (2007). Valuing thoughts, ignoring behavior: the introspection illusion as a source of the bias blind spot. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 43, 565–578 10.1016/j.jesp.2006.05.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeneman T. J. (1981). Reports of the sources of self-knowledge. J. Pers. 49, 284–294 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1981.tb00937.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeneman T. J., Tabor L. E., Nash D. L. (1984). Children’s reports of the sources of self-knowledge. J. Pers. 52, 124–137 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1984.tb00348.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schultheiss O. C. (2008). “Implicit motives,” in Handbook of Personality Psychology: Theory and Research, 3rd Edn, eds John O. P., Robins R. W., Pervin L. A. (New York, NY: Guilford Press; ), 603–633 [Google Scholar]

- Schultheiss O. C., Brunstein J. C. (1999). Goal imagery: bridging the gap between implicit motives and explicit goals. J. Pers. 67, 1–38 10.1111/1467-6494.00046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schultheiss O. C., Brunstein J. C. (2001). Assessing implicit motives with a research version of the TAT: picture profiles, gender differences, and relations to other personality measures. J. Pers. Assess. 77, 71–86 10.1207/S15327752JPA7701_05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedikides C., Horton R. S., Gregg A. P. (2007). The why’s the limit: curtailing self-enhancement with explanatory introspection. J. Pers. 75, 783–824 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00457.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedikides C., Skowronski J. J. (1995). On the sources of self-knowledge: the perceived primacy of self-reflection. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 14, 244–270 10.1521/jscp.1995.14.3.244 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sedikides C., Strube M. J. (1995). The multiply motivated self. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 21, 1330–1335 10.1177/01461672952112010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sedikides C., Strube M. J. (1997). “Self evaluation: to thine own self be good, to thine own self be sure, to thine own self be true, and to thine own self be better,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 29, ed. Zanna M. P. (San Diego, CA: Academic Press; ), 209–269 [Google Scholar]

- Seifert C. F., Yukl G. (2010). Effects of repeated multi-source feedback on the influence behavior and effectiveness of managers: a field experiment. Leadersh. Q. 21, 856–866 10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.07.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silvia P. J., Gendolla G. E. (2001). On introspection and self-perception: does self-focused attention enable accurate self-knowledge? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 5, 241–269 10.1037/1089-2680.5.3.241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. W., Uchino B. N., Berg C. A., Florsheim P., Pearce G., Hawkins M., Yoon H. (2008). Associations of self-reports versus spouse ratings of negative affectivity, dominance, and affiliation with coronary artery disease: where should we look and who should we ask when studying personality and health? Health Psychol. 27, 676–684 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smither J. W., London M., Flautt R., Vargas Y., Kucine I. (2003). Can working with an executive coach improve multisource feedback ratings over time? A quasi-experimental field study. Pers. Psychol. 56, 23–44 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00158.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smither J. W., London M., Reilly R. R., Flautt R., Vargas Y., Kucine I. (2004). Discussing multisource feedback with raters and performance improvement. J. Manage. Dev. 23, 456–468 10.1108/02621710410537065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smither J. W., London M., Richmond K. (2005). The relationship between leaders’ personality and their reactions to and use of multisource feedback: a longitudinal study. Group Organ. Manage. 30, 181–210 10.1177/1059601103254912 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smither J. W., Walker A. G. (2004). Are the characteristics of narrative comments related to improvement in multirater feedback ratings over time? J. Appl. Psychol. 89, 575–581 10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steelman L. A., Rutkowski K. A. (2004). Moderators of employee reactions to negative feedback. J. Manage. Psychol. 19, 6–18 10.1108/02683940410520637 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Storms M. D. (1973). Videotape and the attribution process: reversing actors’ and observers’ points of view. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 27, 165–175 10.1037/h0034782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann W. B., Jr., Pelham B. (2002). Who wants out when the going gets good? Psychological investment and preference for self-verifying college roommates. Self Identity 1, 219–233 10.1080/152988602760124856 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swann W. B., Jr., Read S. J. (1981). Acquiring self-knowledge: the search for feedback that fits. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 41, 1119–1128 10.1037/0022-3514.41.6.1119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vazire S. (2010). Who knows what about a person? The self–other knowledge asymmetry (SOKA) model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 98, 281–300 10.1037/a0017908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazire S., Carlson E. N. (2010). Self-knowledge of personality: do people know themselves? Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 4, 605–620 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00280.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vazire S., Carlson E. N. (2011). Others sometimes know us better than we know ourselves. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 20, 104–108 10.1177/0963721411402478 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vazire S., Mehl M. R. (2008). Knowing me, knowing you: the accuracy and unique predictive validity of self-ratings and other-ratings of daily behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 95, 1202–1216 10.1037/a0013314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazire S., Mehl M. R., Carlson E. N. (2009). Shining a light on the blind spots in self-perception. Talk presented at the 15th European Conference on Personality, Brno [Google Scholar]

- Vohs K. D., Baumeister R. F., Ciarocco N. J. (2005). Self-regulation and self-presentation: regulatory resource depletion impairs impression management and effortful self-presentation depletes regulatory resources. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 88, 632–657 10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagerman S. A., Funder D. C. (2007). Acquaintance reports of personality and academic achievement: a case for conscientiousness. J. Res. Pers. 41, 221–229 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker A. G., Smither J. W. (1999). A five-year study of upward feedback: what managers do with their results matters. Pers. Psychol. 52, 393–423 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1999.tb00166.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T. D. (2002). Strangers to Ourselves: Discovering the Adaptive Unconscious. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press/Harvard University Press [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T. D. (2003). Knowing when to ask: introspection and the adaptive unconscious. J. Conscious. Stud. 10, 131–140 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T. D., Dunn E. W. (2004). Self-knowledge: its limits, value and potential for improvement. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 55, 493–518 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T. D., Gilbert D. T. (2003). “Affective forecasting,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 35, ed. Zanna M. P. (San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press; ), 345–411 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T. D., Hodges S. D., LaFleur S. J. (1995). Effects of introspecting about reasons: inferring attitudes from accessible thoughts. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 69, 16–28 10.1037/0022-3514.69.1.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood J. V., Giordano-Beech M., Taylor K. L., Michela J. L., Gaus V. (1994). Strategies of social comparison among people with low self-esteem: self-protection and self-enhancement. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 67, 713–731 10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]