ABSTRACT

As the use of medical marijuana expands, it is important to consider its implications for the patient–physician relationship. In Colorado, a small cohort of physicians is recommending marijuana, with 15 physicians registering 49% of all medical marijuana patients and a single physician registering 10% of all patients. Together, they have registered more than 2% of the state to use medical marijuana in the last three years. We are concerned that this dramatic expansion is occurring in a setting rife with conflicts of interest despite insufficient scientific knowledge about marijuana. This system diminishes the patient–physician relationship to the recommendation of a single substance while unburdening physicians of their usual responsibilities to the welfare of their patients.

KEY WORDS: physician behavior, patient–doctor relationship, medical marijuana, ethics, cannabis, professionalism

INTRODUCTION

We practice in Colorado, one of sixteen states where it is legal to use marijuana for medical conditions. Many patients tell us that since a doctor recommended they smoke marijuana, it must be good for them. When we ask about their relationship with the recommending doctor, they often acknowledge they saw the doctor once, for a short visit in a marijuana dispensary. This type of encounter narrows the physician–patient relationship to a recommendation to use an otherwise illicit substance. We believe these medical marijuana recommendations separate the privileges and the responsibilities of a physician and erode the relationships between patients and their physicians.

When a physician enters into a relationship with a patient, the physician has a fiduciary responsibility to the welfare of that patient. These responsibilities include providing competent care based on scientific knowledge and maintaining trust by managing conflicts of interest so that the pursuit of any personal gain does not compromise the welfare of patients. These responsibilities are consistent with those listed in the recent “Medical Professionalism in the New Millennium: A Physician Charter,” which was endorsed by specialty boards, organizations, and medical societies around the world1. These ethical responsibilities exist in addition to the legal requirements to practice medicine in a particular community.

Neither the ethical responsibilities nor the legal requirements of medical practice were altered when Amendment 20, a citizen-initiated change to Colorado’s constitution, received 54% of the vote in the November 2000 general election. Amendment 20 did not legalize marijuana, but provided an affirmative defense for the use and possession of marijuana for a debilitating medical condition when recommended by a physician. The amendment enumerates several qualifying diseases (cancer, glaucoma, and AIDS/HIV), but also several conditions (cachexia, severe pain, severe nausea, and persistent muscle spasm) sufficiently non-specific to provide physicians wide latitude to recommend marijuana2. Although recommending marijuana does not violate Colorado’s Medical Practice Act3, we believe that Amendment 20 neglects the welfare of patients by allowing physicians to recommend a substance whose abuse potential is well-documented, but whose benefits are poorly-characterized.

Marijuana has more than 60 known components, and we support the development of purified components that meet regulatory approval. The FDA already approves Marinol®, a synthetic version of ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol, for cachexia associated with HIV/AIDS and refractory nausea and vomiting related to chemotherapy, and Cesamet®, a synthetic cannabinoid for the treatment of nausea and vomiting related to chemotherapy.

Investigators have conducted randomized controlled trials of marijuana itself for the treatment of glaucoma, nausea and vomiting, pain, and cachexia, especially in wasting due to HIV infection. These studies of smoked marijuana have several limitations—small sample size, short duration, heterogeneous study populations, subjective outcomes, differing concentrations of cannabinoids, differing exclusion criteria, lack of active comparators, and difficulty maintaining the study blind4,5. In the rigorous meta-analyses conducted by the Cochrane Collaboration, three separate reviews address the use of marijuana for medical conditions. Investigators found no evidence for the effectiveness of marijuana in dementia6, limited and compromised evidence of effectiveness in Tourette’s syndrome7, and limited and contradictory evidence in schizophrenia8. Marijuana is classified as a Schedule I substance because of its abuse potential, the absence of currently accepted medical uses, and insufficient safety data9, so physicians are prohibited from prescribing marijuana; patients in Colorado and other states where medical marijuana is legal instead receive a physician’s recommendation to use marijuana. As recently as July 2011, the Drug Enforcement Administration again declined to reschedule marijuana from a Schedule I drug to a less restricted schedule10.

Despite limited scientific knowledge, physicians have registered more than 2% of Colorado’s population to use medical marijuana in the last three years. While Amendment 20 became law in 2000, physicians registered fewer than 9,000 Coloradoans by the end of 200811. In March 2009, the Obama administration announced that they would no longer prioritize prosecution of the use and possession of marijuana in states in which it was legal12, and the number of marijuana medical registrants accelerated. Unlike in California, where no state agency registers patients, Colorado’s Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) registers each patient and their recommending physician. The CDPHE makes anonymized data public, allowing for demographic details about who is recommending and using medical marijuana. As of June 30, 2011, the CDPHE reports receiving 148,918 applications and issuing 128,698 medical marijuana registry cards. The CDPHE gives the average age of registrants as 40 years and says 69% of registrants are male. The majority of patients are registered for the non-specific conditions described above rather than for specific diseases, and 94% of patients are registered for “severe pain” as indicated in the Table 1.11

Table 1.

Reported Conditions of Colorado Medical Marijuana Registrants, Through June 30, 2011

| Qualifying condition | Number (and percent) of registrants reporting condition |

|---|---|

| HIV/AIDS | 678 (1%) |

| Glaucoma | 1,156 (1%) |

| Cachexia | 1,653 (1%) |

| Seizures | 1,829 (1%) |

| Cancer | 2,805 (2%) |

| Severe nausea | 15,652 (12%) |

| Muscle spasms | 25,547 (20%) |

| Severe pain | 121,397 (94%) |

Note: patients may be registered for multiple conditions

Until June 2010, physicians were not required to perform any examination—physical, laboratory, or otherwise—to confirm the existence of the qualifying conditions. Physicians had only to agree that a patient had a debilitating medical condition that “may be alleviated by the medical use of marijuana”13. The majority of the currently registered patients, 95,477 of the 128,698 total, were registered under these rules11. Standard medical practice requires diagnostic criteria to support any recommended future plan of action. Since marijuana is neither approved nor standardized by the FDA, physicians who recommend marijuana ought to be especially scrupulous in their diagnosis; instead, they were allowed to lower their diagnostic standards.

Similarly, physicians were not required to see their patients for follow-up visits to assess the benefits of medical marijuana or to be available if complications occurred. The level of recommending physician involvement for medical marijuana fell greatly below that of other accepted forms of medical intervention. A physician prescribing the Schedule II drug Cesamet® would be required to, at minimum, assess their patient’s response to treatment and to monitor the patient for any adverse effects. Even though Cesamet® is a purified and standardized product, while marijuana is an unstandardized raw plant, this physician oversight was not required for medical marijuana.

This ostensibly changed In June 2010, when Colorado Senate Bill 109, which addresses the marijuana patient–physician relationship, became law. Senate Bill 109 requires physicians recommending medical marijuana to have a “bona fide physician–patient relationship,” to complete a “full assessment of the patient’s medical history and current condition”, and to be available for follow-up care. Physicians are now required to have valid, unrestricted licenses from both the DEA and the state of Colorado14. According to Westword, Denver’s alternative newsweekly, 18 physicians who were specializing in medical marijuana are no longer allowed to recommend medical marijuana, apparently because they did not possess valid and unrestricted DEA and Colorado licenses15.

However, we believe Senate Bill 109 does not address the problems inherent in physicians recommending a substance without sufficient scientific knowledge about its safety and efficacy. Unlike opioids, another class of controlled substances with demonstrated abuse potential, marijuana is rarely discussed in medical school or residency. This is problematic, because Amendment 20 does not require specific training in the use of marijuana. When recommending marijuana for a patient, physicians are still not asked to identify who could be harmed by medical marijuana. If they reviewed the published studies of smoked marijuana, they would find that studies often exclude people who have abused other illicit substances, people with a history of mental illness, and inexperienced cannabis users. In contrast, the medical marijuana registry has no exclusion criteria. Recommending physicians do not have to document the failure of other treatments before recommending marijuana13. Physicians are still not required to coordinate care with a patient’s other physicians, and there is no database of medical marijuana users available to physicians as there is for other controlled substances in Colorado. These limitations of the initial amendment and the subsequent statutes mean that physicians who recommend marijuana can simultaneously comply with state law and fail to meet their professional responsibilities to their patient, allowing physicians to practice medicine in a legal but ethically inadequate manner.

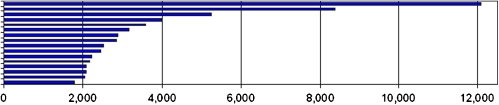

The goal of Senate Bill 109 was to incorporate medical marijuana recommendations into a bona-fide patient–physician relationship, but the available data suggest minimal change in the practice of medical marijuana recommendations. Data generated for this manuscript by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment through January 31, 2011 shows that a small number of physicians recommend the majority of patients. Since the registry opened, 50 physicians have registered 85% of patients, 15 of those physicians have registered 49% of patients, and a single physician has registered 10% of all patients. The number of patients registered by the top 15 physician recommenders is displayed in Figure 1. When looking at the 36,319 recommendations received from July 1, 2010 to January 31, 2011, the period after the enactment of Senate Bill 109, 49% of the recommendations were again from one of fifteen physicians, and a single physician registered 6% of all patients16. Despite the passage of Senate Bill 109, medical marijuana remains the practice of a few physicians.

Figure 1.

Number of medical marijuana registrants, by top 15 physician recommenders. Source: Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, April 2011.

Since many of these physicians’ practices consist principally or exclusively in recommending medical marijuana, a profound conflict of interest is intrinsic to the system. While we recognize that other physicians who specialize in a particular treatment often face this conflict of interest, we believe it is of a different degree when the substance is otherwise illicit and remains a federal crime to use or possess. Unlike physicians who sell nutritional products or provide minor aesthetic procedures in the outpatient setting as part of a full spectrum of primary care services, physicians who recommend marijuana provide patients access to the most frequently abused illicit substance in the state17.

Until June 2010, some physicians heightened this conflict of interest by working as employees of dispensaries, for-profit businesses where marijuana and marijuana-infused products are sold, and seeing patients inside dispensaries. One physician listed his specialty with the medical board as “medical marijuana” and his employer as “CannaMed.” He surrendered his Colorado medical license in December 2010 after being investigated by the state’s medical board for recommending marijuana to a 20-year-old pregnant woman without examining the patient or documenting her pregnancy; her child tested positive for marijuana at birth18. Although his license was suspended for exposing the patient and her fetus to marijuana, there are no contraindications to medical marijuana use agreed upon by either the medical community or listed in Amendment 20 or other Colorado statues precisely because we lack knowledge of marijuana’s safety. Senate Bill 109 prohibits physicians who recommend marijuana from holding “an economic interest in an enterprise that provides or distributes medical marijuana” and from diagnosing within dispensaries14, but dispensaries still advertise their ability to secure speedy physician approval. By September 2010, 809 dispensaries were registered in Colorado, more than a third of all the nation’s dispensaries19. Dispensaries advertise that physician approval fees are around $100. Patients then pay $90 to register with the state, all for the ability to spend around $5,000 for a year’s supply20. In this lucrative system, without third-party payers, in which a physician’s income depends upon recommending a single substance with known abuse potential, the conflict of interest between a physician’s personal gain and the welfare of their patients is profound.

In sum, Colorado’s medical marijuana legislation and industry unburden physicians of their responsibilities to the welfare of their patients by allowing them to act out of insufficient scientific knowledge regarding the effectiveness and safety of marijuana. In this model, physicians are gatekeepers to an otherwise illegal substance, a very thin account of the relationship between a patient and a physician. We believe physicians have further responsibilities to their patients than the medical marijuana legislation and industry require. If marijuana is to be available for medical use, we believe it ought to be regulated, approved, and prescribed like any other medical treatment. Until that occurs, we call on physicians to stop recommending marijuana. If physicians choose to recommend marijuana, we believe this should be done, at minimum, in the context of a longitudinal patient–physician relationship, in the absence of improper financial incentives for the physician, with an honest acknowledgement to patients of the limited scientific knowledge regarding the safety and efficacy of medical marijuana, and only when other, more rigorously studied treatments have failed.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment for providing data for this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest None disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med 2002 136;243–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Colorado Constitution 0-4-287 - ARTICLE XVIII - Miscellaneous Art. XVIII – Miscellaneous. [cited 2011 Aug 8]. Available from: http://www.cdphe.state.co.us/hs/medicalmarijuana/amendment.html.

- 3.Colorado Medical Practice Act Article 12-36-106(B). [cited 2011 Aug 8]. Available from: http://www.dora.state.co.us/medical/Statute.pdf.

- 4.Ben Amar M. Cannabinoids in medicine: a review of their therapeutic potential. J Ethnopharm. 2006;105:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hazekamp A, Grotenhermen F. Review on clinical studies with cannabis and cannabinoids 2005–2009. Cannabinoids. 2010;5:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krishnan S, Cairns R, Howard R. Cannabinoids for the treatment of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007204.pub2. Issue 2. Art. No.: CD007204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Curtis A, Clarke CE, Rickards HE. Cannabinoids for Tourette’s syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006565.pub2. Issue 4. Art. No.: CD006565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Rathbone J, Variend H, Mehta H. Cannabis and schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004837.pub2. Issue 3. Art. No.: CD004837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Watson SJ, Benson JA, Joy JE. Marijuana as medicine: assessing the science base: a summary of the 1999 Institute of Medicine report. Arch Gen Psych. 2000;57:547–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leonhart MM. Denial of petition to initiate proceedings to reschedule marijuana. Federal Register 2011 76:4055–40589. FR Doc No: 2011–16994 [cited 2011 Aug 8]. Available from: http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/fed_regs/rules/2011/fr0708.htm.

- 11.Medical marijuana registry program update [Internet]. Denver (CO): Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, c2011 Jun 30 [cited 2011 Aug 8]. Available from: http://www.cdphe.state.co.us/hs/medicalmarijuana/statistics.html.

- 12.Johnston D, Lewise NA. Obama administration to stop raids on medical marijuana dispensers. The New York Times. 2009 Mar 19. [cited 2011 Aug 8]. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/19/us/19holder.html.

- 13.Medical marijuana registry application [Internet]. Denver (CO): Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, c2011 [cited 2011 Aug 8]. Available from: http://www.cdphe.state.co.us/hs/medicalmarijuana/MEDICAL%20MARIJANA%20REGISTRY%20APPLICATION%20writeable.pdf.

- 14.Colorado Senate Bill 10–109, 2010 Jun 7. [cited 2011 Aug 8]. Available from: http://www.cdphe.state.co.us/hs/medicalmarijuana/109_enr.pdf.

- 15.Roberts M. Nearly 2,000 MMJ patient recommendations nixed over quiet rule change. Westword. 2010 Nov 5. [cited 2011 Aug 8]. Available from: http://blogs.westword.com/latestword/2010/11/medical_marijuana_nearly_2000_mmj_patient_recommendations_nixed_over_quiet_rule_change.php.

- 16.Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, private communication, April 2011.

- 17.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Office of Applied Studies. Treatment Episode Data Set -- Admissions (TEDS-A), 2008 [Computer file]. ICPSR27241-v2. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2010-03-31. doi:10.3886/ICPSR27241 Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) Based on administrative data reported by States to TEDS through Jan 06, 2011 [cited 2011 Aug 8]. Available from: http://wwwdasis.samhsa.gov/webt/quicklink/CO08.htm.

- 18.Ingold J. Colorado doctor accused of faulty medical-pot recommendation may lose license. The Denver Post. 2010 Dec 22. [cited 2011 Aug 8]. Available from: http://www.denverpost.com/news/marijuana/ci_16916444.

- 19.Ingold J. Major changes are at hand for marijuana politics. The Denver Post. 2010 Oct 3. [cited 2011 Aug 8]. Available from: http://www.denverpost.com/search/ci_16239152.

- 20.Ferguson A. The United States of Amerijuana. Time. 2010 Nov 22. [cited 2011 Aug 8]. Available from: http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,2030768,00.html.