Abstract

Background

Both obesity and depression have been associated with significant increases in health care costs. Previous research has not examined whether cost increases associated with obesity could be explained by confounding effects of depression.

Objective

Examine whether the association between obesity and health care costs is explained by co-occurring depression.

Design

Cross-sectional study including telephone survey and linkage to health plan records.

Participants

4462 women aged 40 to 65 enrolled in prepaid health plan in the Pacific Northwest.

Main Measures

The telephone survey included self-report of height and weight and measurement of depression by the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9). Survey data were linked to health plan cost accounting records.

Key Results

Compared to women with BMI less than 25, proportional increases in health care costs were 65% (95% CI 41% to 93%) for women with BMI 30 to 35 and 157% (95% CI 91% to 246%) for women with BMI of 35 or more. Adjustment for co-occurring symptoms of depression reduced these proportional differences to 40% (95% CI 18% to 66%) and 87% (95% CI 42% to 147%), respectively. Cost increases associated with obesity were spread across all major categories of health services (primary care visits, outpatient prescriptions, inpatient medical services, and specialty mental health care).

Conclusions

Among middle-aged women, both obesity and depression are independently associated with substantially higher health care costs. These cost increases are spread across the full range of outpatient and inpatient health services. Given the high prevalence of obesity, cost increases of this magnitude have major policy and public health importance

KEY WORDS: depression, obesity, cost, epidemiology

Obesity is consistently associated with increased use of health services.1–3 For example, a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or more has been associated with a 50% increase in per capita costs, and a BMI of 40 or more has associated with a 100% increase.2,3 Given the high and increasing prevalence of obesity, these increased costs are expected to have large effects on future US health care spending.4,5

Obesity, however, is also associated with depression.6–9 Risk of co-occurring depression increases in step-wise fashion with increasing BMI, especially among women.8,10,11 Odds of depression are 1.5 to 2.5 times as high among women with BMI of 30 or more compared to those of normal weight.12

Depression is also consistently associated with increased use of health services.13–15 Moderate or severe depression (whether identified by treatment records or by screening) is associated with a 50% to 75% increase in per capita health care costs. This association appears consistent across the range of age and severity of medical illness.14,15

It is possible, therefore, that the observed association between obesity and increased health care costs could be explained by the effect of co-occurring depression (i.e. depression confounds the association between obesity and costs). It is also possible that the association between obesity and health care costs varies according to level of depression (i.e. depression moderates the association between obesity and costs). We are not aware of any previous research examining these possibilities.

This report uses data from a population-based sample of middle-aged women to examine how health care costs are associated with obesity and depression. Analyses specifically examine questions regarding confounding (Is the association between obesity and health care costs actually explained by co-occurring depression?) and moderation or effect modification (Is the association between obesity and health care costs similar across different levels of depression?).

METHODS

Setting

Data were collected between November 2003 and February 2005 through a population-based survey of middle-aged women enrolled in Group Health Cooperative, a prepaid health plan serving approximately 600,000 members in Washington and northern Idaho. Most Group Health members are enrolled via employer-purchased contracts, but approximately 20,000 are enrolled via risk-sharing contracts with Medicare and another 20,000 via risk-sharing contracts with Medicaid or other subsidized low-income programs. The Group Health enrollment is demographically similar to the area population. Study participants were recruited from members enrolled at eight Group Health primary care clinics selected for higher rates of minority enrollment. All study procedures were approved by the Group Health Institutional Review Board.

Sample

Data from Group Health’s Breast Cancer Screening program were used to over-sample women expected to have higher BMI. All women aged 40 and older enrolled in Group Health are invited to complete periodic breast cancer risk questionnaires including self-reported height and weight.16 Using these data, women who last reported a BMI of 30 or more were sampled at 100%, women who last reported a BMI less than 30 were sampled at 12%, and women who did not complete a screening questionnaire in the last five years were sampled at 25%. This stratified sampling procedure was intended to increase the efficiency of the survey and to permit correction for differences in response rates. All analyses incorporated sampling weights17 so that results accurately reflect the entire population of women aged 40 to 65.

Recruitment

All sampled participants were mailed an invitation letter including core elements of informed consent (purpose of the study, study procedures, risks, voluntary nature of participation, procedures to protect confidentiality). The letter included a $5 gift card incentive and a phone number through which potential participants could decline further contact. Those who did not decline were contacted by telephone beginning approximately one week after mailing of the invitation letter. Participants received no additional compensation for completing the survey.

Telephone Survey

Surveys were conducted by trained interviewers from Group Health’s survey research program. Each interviewer received at least 8 hours of general interview training and 4 hours of project-specific training. Certification required satisfactory performance in two role-play interviews and two observed interviews. Contact protocols required a minimum of nine contact attempts, including attempts during evening and weekend times.

Each survey began with a detailed consent script repeating all elements of informed consent (study purpose, study procedures, potential risks, privacy of study information), and each participant provided documented oral consent prior to participation.

The telephone survey included self-reported height and weight and the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), a self-report measure of symptoms from the American Psychiatric Association DSM-IV criteria for diagnosis of major depressive episode. Validation studies in the general population as well as in general medical outpatients and medical inpatients have shown excellent agreement between the self-report PHQ and a clinician structured interview.18–21 Possible scores range from 0 to 27 with score between 5 and 9 on this scale representing a mild level of depressive symptoms and a score of 10 or more representing a moderate or severe level.

A related study described elsewhere22 included in-person assessment of a sample of 250 survey respondents reporting BMI or 30 or more. One component of that study examined how height and weight reported during the telephone survey agreed with in-person measurements (by stadiometer and triple-beam balance). Weight was under-reported by an average of 1.35 kg and height was under-reported by an average of 0.002 meters in comparison to direct measurements, Pearson's correlations between measured and self-reported values for height and weight were r = 0.95 and r = 0.98, respectively.

Cost Data

Survey results were linked to health plan cost accounting records for a 12-month period beginning six months before and extending to six months after the survey date. Group Health’s cost accounting system assigns budget-based costs (rather than charges) to every unit of health service (visit, hospital day, laboratory test, prescription) provided at GHC facilities. Services purchased from outside facilities or providers are listed at the cost paid by Group Health. Primary analyses examined total costs for all services provided or paid for by the health plan. Secondary analyses examined costs for five non-overlapping categories of service: primary care visits, outpatient prescriptions, outpatient visits to medical specialists, inpatient medical care, and specialty mental health care (both inpatient and outpatient).

Data Analysis

Data analyses were conducted using SAS/STAT® software, Version 9.1. All analyses incorporate sampling weights to account for the stratified sampling procedure described above and for differential response rates across sampling strata. Each completed survey was assigned a weight equal to the inverse probability of selection times the inverse probability of response for that stratum. As expected, the distribution of total health care costs was highly skewed and approximated a log-normal distribution. Consequently, comparisons of total costs across PHQ and BMI categories were conducted using gamma regression with a log link. Model results for total costs should therefore be interpreted in terms of proportional or multiplicative differences (e.g. 25% increase in total costs) rather than absolute or additive differences (e.g. $750 difference in total costs). Costs for inpatient medical care and specialty mental health care were highly skewed with half or more of participants having zero costs and a small number having high costs. Consequently, statistical comparisons for cost categories used nonparametric methods (Kruskal–Wallis Rank Sum Test).

RESULTS

Of 8000 potential participants who were mailed invitation letters, 442 were found to be ineligible (had since died, moved away, or disenrolled from the health plan). Of the remaining 7558 eligible women, 865 could not be reached by telephone and 2033 declined to participate, leaving 4660 participants (62% of those eligible). Participation was not related to age or history of depression treatment, but did vary significantly across sampling strata (63% among those previously reporting BMI > = 30 vs. 59% among those previously reporting BMI <30 vs. 34% among those declining to participate in breast cancer screening, X2 = 344, df = 2, p < 0.001). As discussed above, all analyses incorporated sampling weights to correct for differential response across strata. Analyses of cost data were limited to the 4462 women continuously enrolled in the health plan from six months prior to the survey until six months after. This sample had a mean age of 52, 80% were Caucasian, 61% were married, 63% were employed, and 49% were college graduates.

As reported previously,12 33.4% of respondents reported BMI of 30 or greater (the conventional threshold for obesity), and 7.7% had PHQ scores of 10 or more (the conventional threshold for moderate symptoms of depression). Those with BMI of 30 or greater were significantly more likely to have a PHQ score of 10 or more (OR = 2.82, 95% Conf. Interv. = 2.20 to 3.62). The unweighted numbers of participants with specific combinations of BMI and depression severity are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of Respondents (Unweighted) in BMI and PHQ Score Strata

| BMI <25 | BMI 25 to 30 | BMI 30 to 35 | BMI >35 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ <5 | 1341 | 764 | 449 | 303 | 2857 |

| PHQ 5 to 9 | 282 | 287 | 222 | 231 | 1022 |

| PHQ > =10 | 111 | 140 | 141 | 191 | 583 |

| Total | 1734 | 1191 | 812 | 725 | 4462 |

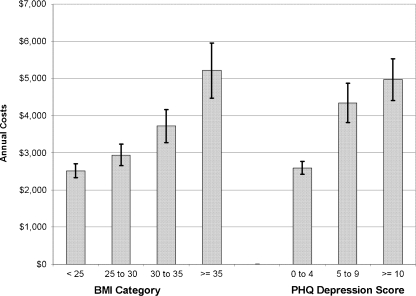

Annual health services costs increased in step-wise fashion with increasing BMI and with increasing severity of depression (Fig. 1). In a regression model adjusting for age, total health care costs varied significantly across categories of BMI (X2 = 52.25, df = 3, p = < 0.001). When depression score was added to this model, BMI category remained a highly significant predictor of log-transformed cost (X2 = 26.49, df = 3, p = 0.003). After adjustment for co-occurring symptoms of depression, proportional increases in cost with increasing BMI were smaller, but the pattern was qualitatively unchanged: Cost increased in step-wise fashion with increasing BMI and all of the overweight or obese groups were significantly different from the normal-weight reference group (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Annual health care costs (with 95% confidence limits) according to BMI or depression severity.

Table 2.

Proportional Increase in Total Health Care Costs with Increasing BMI, with and Without Adjustment for Symptoms of Depression

| Adjusted for age only | Adjusted for age and PHQ depression score | |

|---|---|---|

| BMI <25 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| BMI 25 to 30 | 1.30 (1.15 to 1.48) | 1.15 (1.02 to 1.31) |

| BMI 30 to 35 | 1.65 (1.41 to 1.93) | 1.40 (1.18 to 1.66) |

| BMI >35 | 2.57 (1.91 to 3.46) | 1.87 (1.42 to 2.47) |

Tabled values are proportional differences with 95% confidence intervals based on gamma regression with log link

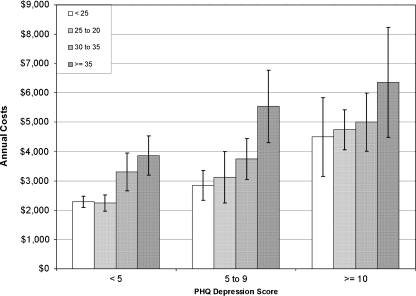

Across all levels of PHQ depression score, annual health services costs increased in a step-wise fashion with increasing BMI (Fig. 2). In a regression model predicting total cost as a function of age, BMI category, and depression score category (Table 3), the proportional increase in costs with increasing BMI appeared generally similar across different strata of depression severity. Nevertheless, a formal test for interaction effect found that the relationship between total costs and BMI varied across depression categories more than expected by chance (X2 = 19.99, df = 6, p = 0.003).

Figure 2.

Annual health care costs (with 95% confidence limits) according to BMI, stratified by depression severity.

Table 3.

Proportional Increase in Total Health Care Costs Across Strata Defined by Both BMI and PHQ Depression Score

| PHQ 0 to 4 | PHQ 5 to 9 | PHQ 10 or more | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI <25 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.46 (1.24 to 1.73) | 1.79 (1.27 to 2.50) |

| BMI 25 to 30 | 1.09 (0.94 to 1.27) | 2.10 (1.68 to 2.62) | 2.20 (1.60 to 3.03) |

| BMI 30 to 35 | 1.34 (0.94 to 1.91) | 1.84 (1.18 to 2.88) | 2.66 (2.07 to 3.42) |

| BMI >35 | 1.72 (1.07 to 2.76) | 4.14 (2.92 to 5.85) | 3.90 (2.82 to 5.38) |

Tabled values are proportional differences with 95% confidence intervals based on gamma regression with log link

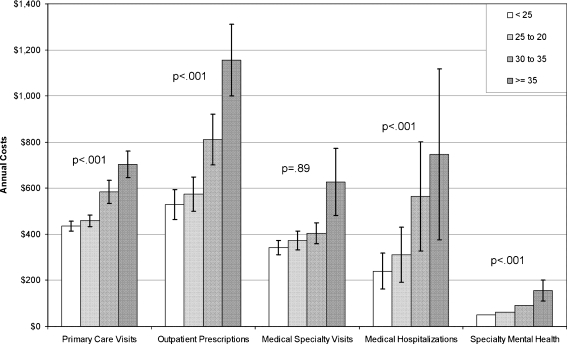

The association between BMI and health care costs was generally similar across different categories of health services (Fig. 3). Costs of medical specialty care did not vary across BMI categories more than expected by chance. For every other category, costs increased in step-wise fashion with increasing BMI, and the variation across categories of BMI far exceeded that expected by chance (p < 0.001 for all comparisons by Kruskal–Wallis Rank Sum Test). The proportional increase in costs with increasing BMI appeared greater for outpatient prescriptions and inpatient medical care than for other categories of costs.

Figure 3.

Categories of health care costs (with 95% confidence limits) according to BMI.

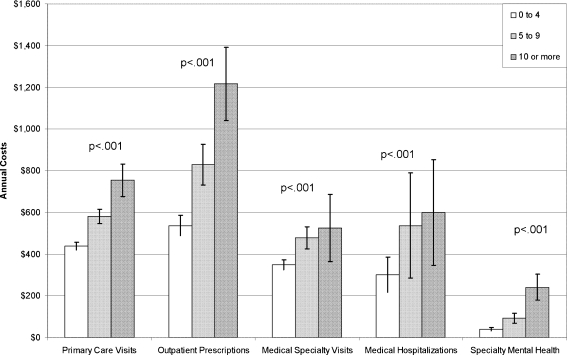

Similarly, the association between depression severity and health care costs was similar across different categories of health services (Fig. 4). For every category of health service, costs increased in step-wise fashion with increasing depression score. This relationship was highly significant (p < 0.001 by Kruskal–Wallis Rank Sum Test) for all cost categories. The proportional increase in costs with increasing depression score appeared greater for primary care visits and specialty mental health care than for other categories of cost. Even among those with PHQ depression scores of 10 or more, however, specialty mental health care costs accounted for only approximately 5% of total costs.

Figure 4.

Categories of health care costs (with 95% confidence limits) according to PHQ depression score.

When distributions are highly skewed (as for inpatient costs and specialty mental health costs), means may not accurately reflect central tendency. Alternative versions of Figures 3 and 4 using medians or 5% trimmed means showed qualitatively similar relationships (details available on request).

DISCUSSION

In this sample of middle-aged women, we confirm previous findings that both obesity and depression are associated with increased health care costs. Overall health care costs were more than twice as high for women with severe or morbid obesity (BMI of 35 or more) than for women of normal weight. Health care costs were nearly twice as high for women with at least moderate symptoms of depression (PHQ depression score of 10 or more) than for women without significant symptoms of depression. We find only modest evidence for confounding. While our analyses find statistically significant effect modification, the pattern of increasing cost with increasing BMI appeared similar across all different levels of depression severity.

Our findings indicate that most of the previously reported association between obesity and health care costs is not explained by the confounding effect of co-occurring depression. Annual costs for women with BMI of 35 or greater were approximately 150% higher than for women with BMI less than 25, and adjustment for co-occurring depression reduced this proportional difference to approximately 90%. We should add that adjustment for potential confounding may not be appropriate if overlapping effects instead reflect mediation.23 For example, obesity may lead to increased health care costs because it increases risk for depression and depression increases health care costs. In such a scenario, adjusting away the effect of co-occurring depression would under-estimate the true association between obesity and health care costs.

While our analyses indicate a statistically significant interaction effect, but the observed level of effect modification is probably not meaningful. Examination of Figure 2 indicates that the relationship between obesity and health care costs was qualitatively similar for women with different levels of depression. Nevertheless, a regression model predicting proportional differences in cost did find that the association between obesity and depression varied more than expected by chance across different levels of depression. In this large sample, differences that are not meaningful from a clinical or public health perspective may still exceed the 5% level of statistical significance. More important, the result of a statistical test for interaction may differ depending on whether costs are analyzed on the original scale or after logarithmic transformation. Across all levels of depression, the proportional change in total costs with increasing BMI was generally similar: costs were approximately twice as high for those with BMI above 35 (morbid obesity) than for those with BMI below 25 (normal weight). But the absolute change in total costs appeared greater at higher levels of depression (a difference of approximately $2000 for those with higher depression scores compared to approximately $1500 for those with lower depression scores).

The associations between obesity and health care costs or between depression and health care costs were not confined to any specific type of health service. As in previous studies,13–15 only a small proportion of the added costs associated with depression could be associated with depression treatment. The magnitude of the association between obesity and health care costs did appear greater for outpatient prescriptions and medical hospitalizations. And the association between depression and health care costs did appear greater for primary care visits and mental health specialty care. Nevertheless, most individual categories of health care costs increased in step-wise fashion with both increasing severity of depression and increasing BMI.

At least some of the association between obesity and costs is likely explained by chronic health conditions. For example, obesity may increase risk of diabetes or heart disease leading to increased use of health services. In this scenario, chronic health conditions would be considered a mediator rather than confounder.

The relationships among depression, chronic illness, and health care costs are probably more complex. Depression might increase risk of chronic illness by influencing health behaviors (such as diet, exercise, or tobacco use) or through biological mechanisms (such as neuroendocrine systems or inflammatory pathways).24 In these cases, chronic illness would be a mediator of the association between depression and health care costs. Alternatively, both depression and increased use of health services could be consequences of chronic illness. In this case, chronic illness would be considered a confounder. Finally, depression might increase use of health services independent of chronic illness by increasing help-seeking for unexplained or ill-defined physical symptoms.

These observational data cannot prove causal relationships. It is possible that the associations among obesity, depression, and health care costs are actually explained by some preceding factor that increases risk of obesity and depression while also increasing use of health services. For example, childhood adversity or socioeconomic disadvantage may increase risk of both obesity and depression.25 In the case of this type of confounding, we would not expect that interventions directed at reducing the prevalence of either obesity or depression would lead to lower health care costs. Previous research, however, does indicate that improvement in depression is associated with decreases in health care costs.26,27 Fewer studies have examined changes in health care costs associated with weight loss, but some suggest that weight loss following obesity surgery is associated with decreases in health care costs.28–31

Interpretation of these results should consider some important limitations. First, our sample was limited to women aged 40 to 65, and we cannot know if these results would generalize to men or to other age groups. Second, only 62% of potential participants completed the survey, and we cannot exclude the possibility that the relationships among obesity, depression, and health care costs were different in non-participants. Third, assessment of depression was limited to symptoms during the past two weeks, and this method would not capture fluctuations in depression (either naturally occurring or resulting from treatment) during the 12-month period used to calculate health care costs. Fourth, obesity was assessed by self-reported BMI when waist circumference may be a stronger predictor of both depression and adverse health consequences.32,33 Fifth, our analyses focus on mild and moderate depression because our sample included few women with PHQ scores greater than 20.

We conclude that both obesity and depression are independently associated with substantial increases in health care costs. The cost increases associated with both obesity and depression are spread across the full range of outpatient and inpatient health services. Regarding the association between depression and health care costs, we find that the absolute increase in costs associated with depression is greatest among the overweight and obese. This suggests that efforts to improve recognition and management of depression among the overweight and obese may, like previous efforts among those with chronic medical illness,34–37 help to reduce overall health care costs. Regarding the association between obesity and health care costs, we confirm previous findings regarding the excess health care costs associated with overweight or obesity and add that this association is not confounded by co-occurring depression. Given the implications of increasing obesity rates for future health care costs,4,5 more effective prevention of obesity is an economic imperative.

Acknowledgments

Contributors All listed authors made substantive contributions to the design and conduct of this study; all made substantive contributions to the drafting and/or editing of this manuscript.

Other Contributors There are no other individuals who made substantial contributions but do not meet criteria for authorship.

Funding Funded by NIMH grant R01 MH068127

Prior Presentation N/A

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Bertakis KD, Azari R. Obesity and the use of health care services. Obes Res. 2005;13(2):372–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quesenberry CP, Jr, Caan B, Jacobson A. Obesity, health services use, and health care costs among members of a health maintenance organization. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(5):466–72. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.5.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreyeva T, Sturm R, Ringel JS. Moderate and severe obesity have large differences in health care costs. Obes Res. 2004;12(12):1936–43. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daviglus ML, Liu K, Yan LL, et al. Relation of body mass index in young adulthood and middle age to Medicare expenditures in older age. JAMA. 2004;292(22):2743–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.22.2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai L, Lubitz J, Flegal KM, Pamuk ER. The predicted effects of chronic obesity in middle age on Medicare costs and mortality. Med Care. 2010;48(6):510–7. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181dbdb20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onyike C, Crum R, Lee H, Lyketsos C, Eaton W. Is obesity associated with major depression? Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:1139–47. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heo M, Pietrobelli A, Fontaine K, Sirey J, Faity M. Depressive mood and obesity in US adults: comparison and moderation by sex, age, and race. Int J Obes. 2005;(epub Nov 15). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Ma J, Xiao L. Obesity and depression in US women: results from the 2005–2006 National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(2):347–53. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao G, Ford ES, Dhingra S, Li C, Strine TW, Mokdad AH. Depression and anxiety among US adults: associations with body mass index. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009;33(2):257–66. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon G, Ludman E, Linde J, et al. Association between obesity and depression in middle-aged women. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:32–9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon G, VonKorff M, Saunders K, et al. Association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:824–30. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Linde JA, et al. Association between obesity and depression in middle-aged women. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(1):32–9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, Barlow W. Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiat. 1995;152:352–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simon G, VonKorff M, Barlow W. Health care costs of primary care patients with recognized depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:850–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950220060012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unützer J, Patrick D, Simon G, et al. Depressive symptoms and the cost of health services in HMO patients age 65 and over: a four-year prospective study. JAMA. 1997;277:1618–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.20.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taplin S, Thompson R, Schintzer F, Anderman C, Immanuel V. Revisions in the risk-based Breast Cancer Screening Program at Group Health Cooperative. Cancer. 1990;66:812–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900815)66:4<812::AID-CNCR2820660436>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cochran W. Sampling techniques. New York: Wiley; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang F, Chung H, Kroenke K, Delucchi K, Spitzer R. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to measure depression among racially and ethnically diverse primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:547–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams J. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, Grafe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) J Affect Disord. 2004;81:61–6. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams J. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linde JA, Simon GE, Ludman EJ, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Behavioral Weight Loss Treatment versus Combined Weight Loss/Depression Treatment among Women with Comorbid Obesity and Depression. Ann Behav Med. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Weinberg C. Toward a clear definition of confounding. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:1–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katon WJ. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):216–26. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rohde P, Ichikawa L, Simon GE, et al. Associations of child sexual and physical abuse with obesity and depression in middle-aged women. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32(9):878–87. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon G, Chisholm D, Treglia M, Bushnell D. Course of depression, health services costs, and work productivity in an international primary care study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24:328–35. doi: 10.1016/S0163-8343(02)00201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simon G, Revicki D, Heiligenstein J, et al. Recovery from depression, work productivity, and health care costs among primary care patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22:153–62. doi: 10.1016/S0163-8343(00)00072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McEwen LN, Coelho RB, Baumann LM, Bilik D, Nota-Kirby B, Herman WH. The cost, quality of life impact, and cost-utility of bariatric surgery in a managed care population. Obes Surg. 2010;20(7):919–28. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sampalis JS, Liberman M, Auger S, Christou NV. The impact of weight reduction surgery on health-care costs in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 2004;14(7):939–47. doi: 10.1381/0960892041719662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cremieux PY, Buchwald H, Shikora SA, Ghosh A, Yang HE, Buessing M. A study on the economic impact of bariatric surgery. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(9):589–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makary MA, Clarke JM, Shore AD, et al. Medication utilization and annual health care costs in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus before and after bariatric surgery. Arch Surg. 2010;145(8):726–31. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rivenes AC, Harvey SB, Mykletun A. The relationship between abdominal fat, obesity, and common mental disorders: results from the HUNT study. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66(4):269–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marijnissen RM, Bus BA, Holewijn S, et al. Depressive symptom clusters are differentially associated with general and visceral obesity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):67–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katon W, Unutzer J, Fan M, et al. Cost-effectiveness and net benefit of enhanced treatment of depression for older adults with diabetes and depression. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:265–70. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katon WJ, Russo JE, Korff M, Lin EH, Ludman E, Ciechanowski PS. Long-term effects on medical costs of improving depression outcomes in patients with depression and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(6):1155–9. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simon GE, Katon WJ, Lin EH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of systematic depression treatment among people with diabetes mellitus. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(1):65–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unutzer J, Katon WJ, Fan MY, et al. Long-term cost effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(2):95–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]