Abstract

Rationale: Obesity has been linked to acute lung injury and is a risk factor for early mortality after lung transplantation.

Objectives: To examine the associations of obesity and plasma adipokines with the risk of primary graft dysfunction after lung transplantation.

Methods: We performed a prospective cohort study of 512 adult lung transplant recipients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or interstitial lung disease enrolled in the Lung Transplant Outcomes Group Study. In a nested case-control study, we measured plasma leptin, adiponectin, and resistin before lung transplantation and 6 and 24 hours after lung transplantation in 40 cases of primary graft dysfunction and 80 control subjects. Generalized linear mixed models and logistic regression were used to estimate risk ratios and odds ratios.

Measurements and Main Results: Grade 3 primary graft dysfunction developed within 72 hours of transplantation in 29% participants. Obesity was associated with a twofold increased risk of primary graft dysfunction (adjusted risk ratio 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 1.7–2.6). The risk of primary graft dysfunction increased by 40% (confidence interval, 30–50%) for each 5 kg/m2 increase in body mass index after accounting for center, diagnosis, cardiopulmonary bypass, and transplant procedure. Higher plasma leptin levels were associated with a greater risk of primary graft dysfunction (sex-adjusted P = 0.02). The associations of both obesity and leptin with primary graft dysfunction tended to be stronger among those who did not undergo cardiopulmonary bypass.

Conclusions: Obesity is an independent risk factor for primary graft dysfunction after lung transplantation.

Keywords: acute lung injury, leptin, lung transplantation, obesity, primary graft dysfunction

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Obesity is a risk factor for both adult respiratory distress syndrome and mortality after lung transplantation. Leptin may play a role in the development and sequelae of acute lung injury.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Obesity is an independent risk factor for primary graft dysfunction after lung transplantation. Plasma leptin levels are higher among those with primary graft dysfunction.

Lung transplantation is an effective treatment for advanced lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and the interstitial lung diseases (ILDs). Primary graft dysfunction (PGD), defined as the occurrence of acute lung injury (ALI) in the allograft within 72 hours of transplantation (1), is a leading cause of death early after lung transplantation (2) and is a risk factor for chronic allograft rejection (3, 4). Although PGD is typically attributed to ischemia–reperfusion injury of the allograft, systemic inflammation plays a critical role (5–7).

Obesity is a state of positive energy balance characterized by a chronic systemic inflammatory state (8). Emerging evidence suggests that obesity is a novel risk factor for ALI among the critically ill (9, 10), perhaps by altering the milieu of proinflammatory and antiinflammatory cytokines produced by adipose tissue (so-called “adipokines”) (11–13), such as leptin and adiponectin. Leptin in particular has been shown to play a role in the development of ALI in a hyperoxia mouse model and to contribute to the fibroproliferative stage of the acute respiratory distress syndrome (12, 13).

A number of studies suggest that obesity is a risk factor for death after lung transplantation (14–21), with most of the risk attributable to obesity occurring within the first year after lung transplantation for COPD and ILD (21). Based on these data and the growing evidence supporting a link between obesity and ALI, we hypothesized that obesity would be associated with an increased risk of PGD in lung transplant recipients independent of diagnosis, use of cardiopulmonary bypass, and transplant procedure type, and that PGD would be associated with higher plasma leptin and resistin and lower plasma adiponectin levels.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

We performed a cohort study using the Lung Transplant Outcomes Group (LTOG) cohort. LTOG is an NHLBI-funded prospective cohort study of lung transplant recipients with the primary aim of examining clinical and genetic risk factors for PGD at nine United States centers (a full list of investigators and participating centers appears before the References section) (22–28). Based on a reported association between obesity and early mortality after lung transplantation for COPD and ILD (21), we restricted our study sample to 512 adult LTOG participants with COPD or ILD who underwent single or bilateral lung transplantation between March 2002 and July 2009 and who had complete exposure and outcome data. To investigate possible mechanisms of the association between obesity and PGD, we also performed a nested case-control study of LTOG participants to examine associations between plasma adipokine levels and PGD. A nested case-control study design permits the study of biomarker risk factors using a fraction of the available cohort (thereby preserving biologic samples) with only a small loss in statistical power (29). We randomly selected 40 cases with PGD from the cohort and 80 controls who were frequency matched on diagnosis and procedure type to the cases. The Institutional Review Boards at each site approved the study and written informed consent was obtained from each participant before lung transplantation.

Measurements and Variables

Body weight and height were measured immediately before lung transplantation by clinical personnel and reported to LTOG or the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Chest radiographs were obtained daily for 3 days after lung transplantation. The Pao2 was measured in clinical laboratories at each center. Clinical data were collected by trained personnel on preformatted case report forms. Blood was drawn in citrated tubes before allograft reperfusion and at 6 and 24 hours after allograft reperfusion. Plasma samples were centrifuged within 30 minutes and then stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis.

Exposure Definition

The independent variable was body mass index (BMI), calculated as body weight (in kilograms) divided by body height squared (in meters). We used World Health Organization categories for obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2); overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2); and normal and underweight (BMI <25 kg/m2) (30). We measured plasma leptin, adiponectin, and resistin in duplicate using commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The interassay coefficients of variation for these assays in our laboratory are less than 6% for leptin (n = 4), less than 14% for adiponectin (n = 4), and less than 8.5% for resistin (n = 6), and the intraassay coefficients of variation are less than 7% for leptin (n = 8) and less than 5% for adiponectin (n = 9) and resistin (n = 9). Laboratory personnel were masked to all clinical information.

Outcome Definitions

Chest radiographs were transmitted and interpreted centrally by two trained physicians who adjudicated the presence or absence of new parenchymal infiltrates in the lung allografts consistent with pulmonary edema at 24, 48, and 72 hours after lung transplantation. Chest radiograph reviewers were masked to other clinical information. The primary outcome was grade 3 PGD defined as the presence of new parenchymal infiltrates in the lung allografts consistent with pulmonary edema and a Pao2 to Fio2 ratio of less than 200 at any time within 72 hours of lung transplantation (1, 23, 24, 26, 31). In a secondary analysis, we examined grade 3 PGD present at the 72-hour time point.

Statistical Analysis

We summarized continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as frequency (percentage). The distributions of continuous variables were examined by inspection of histograms and skewness and kurtosis. We used generalized linear mixed models with a Poisson error distribution and a robust variance estimator for fixed effects and an overdispersion component to estimate risk ratios and standard errors (32–34). All models included a random intercept for study center to account for clustering within centers. We purposefully selected potential confounders and precision variables for inclusion in multivariable models based on a plausible association with obesity, PGD, or both. Generalized estimating equations and logistic regression were used to examine associations between log-transformed biomarker levels and PGD (35). We also explored the linearity of the relationships between our exposures of interest and PGD using logistic regression with a loess smoother for BMI (36). We used a Markov chain Monte Carlo method of multiple imputation to account for missing covariate data (37, 38). With α = 0.05, a total sample size of 500, and a 20% risk of PGD among unexposed, we had 84% power to detect risk ratios of 1.7 among recipients who were overweight and 1.8 among recipients who were obese. Statistical analyses were performed using the Glimmix procedure in SAS (version 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and the “gam” procedure in R (version 2.8.1, R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

Results

There were 592 LTOG participants with COPD or ILD who underwent single or bilateral lung transplantation between March 2002 and July 2009. We excluded 12 who were missing PGD data and 68 missing height or weight, leaving 512 included in the analysis. Of these, 224 were normal or underweight, 197 were overweight, and 91 were obese. The mean ± SD age was 58 ± 8 years, 51% were male, 49% had ILD, 52% underwent bilateral lung transplantation, and 27% underwent cardiopulmonary bypass during transplantation. One hundred forty-nine (29%) had grade 3 PGD within 72 hours, and 63 (12%) had grade 3 PGD at the 72-hour time point.

Compared with participants who were normal weight and underweight, participants who were overweight and obese were more likely to have ILD and undergo cardiopulmonary bypass (Table 1). Participants who were overweight and obese also tended to have longer ischemic times, and systolic pulmonary artery pressure at the time of transplantation tended to be higher among participants who were obese.

TABLE 1.

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

| Variable | No. | Normal/Underweight | Overweight | Obese |

| No. | 512 | 224 | 197 | 91 |

| Age, yr | 512 | 58 ± 8 | 59 ± 5 | 57 ± 8 |

| Male, % | 512 | 110 (49%) | 111 (56%) | 41 (45%) |

| Diagnosis, % | 512 | |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 140 (63%) | 91 (46%) | 30 (33%) | |

| Interstitial lung disease | 84 (38%) | 106 (54%) | 61 (67%) | |

| Systolic pulmonary artery pressure, mm Hg | 418 | 39 ± 16 | 40 ± 15 | 46 ± 15 |

| Transplant procedure type, % | 512 | |||

| Single | 101 (45%) | 90 (46%) | 54 (59%) | |

| Double | 123 (55%) | 107 (54%) | 37 (41%) | |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass, % | 512 | 52 (23%) | 55 (28%) | 31 (34%) |

| Ischemic time, min | 497 | 295 ± 104 | 303 ± 97 | 398 ± 99 |

| Donor age, yr | 450 | 35 ± 14 | 35 ± 14 | 35 ± 12 |

| Donor Pao2 on 100% FIo2 | 444 | 493 ± 95 | 487 ± 83 | 492 ± 82 |

Data are mean ± SD and frequency (percentage).

Percentages may not sum to 100% because of rounding.

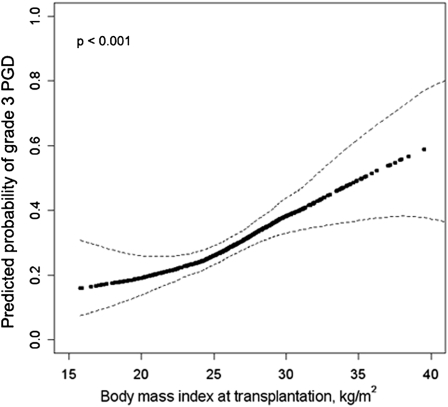

Higher BMI was associated with an increased risk of grade 3 PGD (Figure 1) (P for association < 0.001; P for linearity = 0.35). After accounting for center, diagnosis, cardiopulmonary bypass, and transplant procedure, a 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI was associated with a 40% increase in the risk of grade 3 PGD within 72 hours (P < 0.001; Model 2 in Table 2). The risk of grade 3 PGD within 72 hours increased across BMI categories (P for trend < 0.001). Obesity was associated with a two-fold greater risk of PGD within 72 hours compared with normal weight (adjusted risk ratio 2.1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.7–2.7; Model 2 in Table 2). Additional adjustment for pulmonary artery pressure, ischemic time, donor oxygenation, and donor age did not change these findings (Model 3 in Table 2). Examination of an alternate PGD definition (grade 3 PGD at 72 h) showed similar findings (Table 2). In a post hoc analysis, we further adjusted for tidal volume on the first postoperative day in the subgroup (n = 269) who underwent transplantation since 2007 (the period during which tidal volume data was recorded in LTOG). The association between BMI and the risk of grade 3 PGD within 72 hours remained largely unchanged (risk ratio 1.3 per 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI; 95% CI, 1.1–1.6; P < 0.001 after adjustment for all covariates in Model 3 plus tidal volume). Additional adjustment for the panel reactive antibody level also did not substantially change our findings in the subset who had panel reactive antibody data (adjusted risk ratio 1.5 per 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI; 95% CI, 1.1–1.9; P = 0.005; n = 208).

Figure 1.

Continuous association between body mass index and grade 3 primary graft dysfunction (PGD) adjusted for diagnosis, cardiopulmonary bypass, and transplant procedure type. Dark dotted line = effect estimate. Thin dashed lines = 95% confidence bands. The P value is for the association between body mass index and PGD.

TABLE 2.

RISK RATIOS FOR THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN PREOPERATIVE BODY MASS INDEX AND GRADE 3 PRIMARY GRAFT DYSFUNCTION

| BMI Category |

Continuous BMI |

||||||

| No. | Normal/Underweight BMI <25 kg/m2 | Overweight BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2 | Obese BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | P Trend | Risk Ratio (95% CI) per 5 kg/m2 Increase | P Value | |

| PGD grade 3 within 72 h | |||||||

| Risk | 512 | 17% | 37% | 42% | <0.001 | ||

| Model 1 | 512 | 1 (Ref) | 2 (1.5–2.8) | 2.4 (1.9–3.1) | <0.001 | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 512 | 1 (Ref) | 1.9 (1.4–2.6) | 2.1 (1.7–2.7) | <0.001 | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | <0.001 |

| Model 3 | 512 | 1 (Ref) | 1.9 (1.4–2.6) | 2.1 (1.7–2.6) | <0.001 | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | <0.001 |

| PGD grade 3 at 72 h | |||||||

| Risk | 512 | 8% | 15% | 19% | <0.001 | ||

| Model 1 | 512 | 1 (Ref) | 1.9 (1.1–3.4) | 2.5 (1.4–4.2) | <0.001 | 1.5 (1.3–1.8) | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 512 | 1 (Ref) | 1.7 (1.1–2.7) | 1.9 (1.2–3.1) | 0.004 | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) | 0.001 |

| Model 3 | 512 | 1 (Ref) | 1.8 (1.1–2.9) | 1.9 (1.2–2.9) | 0.003 | 1.4 (1.1–1.6) | <0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; PGD = primary graft dysfunction.

Effect estimates are risk ratios (95% confidence intervals).

Model 1: Unadjusted model with a random intercept for study center.

Model 2: Adjusted for diagnosis, use of cardiopulmonary bypass, and transplant procedure (bilateral vs. single) with a random intercept for study center.

Model 3: Model 2 + adjustment for systolic pulmonary artery pressure, ischemic time, donor oxygenation, and donor age.

We performed analyses stratified by cardiopulmonary bypass and diagnosis (Table 3). The association between BMI and PGD was somewhat stronger among those who did not receive cardiopulmonary bypass (adjusted risk ratio 1.5; 95% CI, 1.3–1.7) compared with those who received cardiopulmonary bypass (adjusted risk ratio 1.2; 95% CI, 1–1.5; P for interaction = 0.08). The association between BMI and PGD did not vary by diagnosis (Table 3) (P for interaction = 0.40).

TABLE 3.

RISK RATIOS FOR THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN PREOPERATIVE BODY MASS INDEX AND GRADE 3 PRIMARY GRAFT DYSFUNCTION WITHIN 72 HOURS STRATIFIED BY DIAGNOSIS AND USE OF CARDIOPULMONARY BYPASS

| BMI Category |

Continuous BMI |

|||||||

| No. | BMI <25 kg/m2 | BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2 | BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | P Trend | Risk Ratio (95% CI) per 5 kg/m2 Increase | P Value | P for Interaction | |

| Stratified by use of CBP | ||||||||

| CBP | 137 | 1 (Ref) | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | <0.001 | 1.2 (1.02–1.5) | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| No CBP | 375 | 1 (Ref) | 2.1 (1.3–3.5) | 2.7 (1.9–4) | <0.001 | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | <0.001 | |

| Stratified by diagnosis | ||||||||

| COPD only | 261 | 1 (Ref) | 2 (1.3–3) | 2.4 (1.1–5) | 0.01 | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.006 | 0.40 |

| ILD only | 251 | 1 (Ref) | 1.8 (1.2–2.7) | 1.8 (1.1–2.8) | 0.002 | 1.3 (1.2–1.5) | <0.001 | |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CBP = cardiopulmonary bypass; CI = confidence interval; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ILD = interstitial lung disease; PGD = primary graft dysfunction.

Effect estimates are risk ratios (95% confidence intervals). Models are adjusted for transplant procedure (bilateral vs. single), systolic pulmonary artery pressure, ischemic time, donor oxygenation, and donor age with a random intercept for study center. Models stratified by cardiopulmonary bypass are adjusted for diagnosis. Models stratified by diagnosis are adjusted for use of cardiopulmonary bypass.

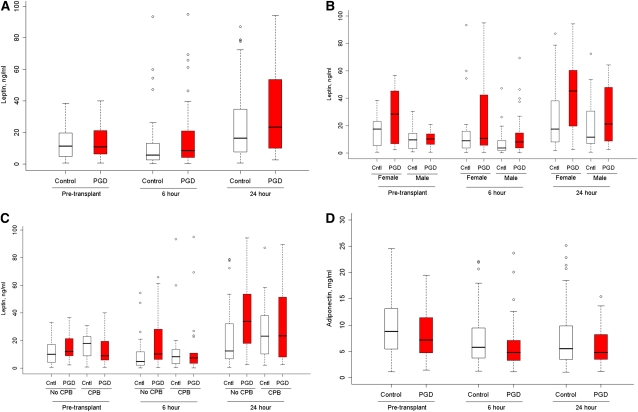

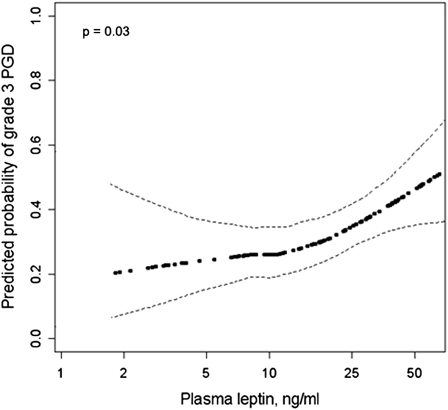

Higher plasma leptin levels were associated with an increased risk of PGD (Table 4, Figure 2A) (P = 0.04). Leptin levels are known to be higher among women compared with men after accounting for adiposity (39). Therefore, we also examined sex-adjusted (Table 4) (P = 0.02) and sex-stratified (Figure 2B) results, which were similar to unadjusted results. Figure 3 shows the sex-adjusted continuous association between the 24-hour plasma leptin level and PGD (adjusted odds ratio 1.6 per natural log increase; 95% CI, 1.1–2.3; P = 0.03). The association between plasma leptin and PGD varied by the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (Figure 2C) (P for interaction = 0.02), with stronger associations between plasma leptin and PGD among those who did not receive cardiopulmonary bypass (adjusted odds ratio for the 24-h leptin level 2.1; 95% CI, 1.2–3.9) compared with those who did (adjusted odds ratio for the 24-h leptin level 1.1; 95% CI, 0.6–2). There were no significant interactions between plasma leptin and sex or diagnosis (P values for interaction ≥ 0.65). There were no significant associations between PGD and either plasma adiponectin or resistin (Table 4, Figure 2D). Greater BMI was associated with higher plasma leptin levels (case-adjusted partial Pearson correlation coefficient for 24-h leptin level and BMI = 0.26; P = 0.007) and tended to be associated with lower plasma adiponectin levels (case-adjusted partial Pearson correlation coefficient for 24-h adiponectin level and BMI = −0.19; r = 0.051), but was not associated with plasma resistin levels (r = 0.11; P = 0.29).

TABLE 4.

ODDS RATIOS FOR THE ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN PRIMARY GRAFT DYSFUNCTION AND PLASMA ADIPOKINE LEVELS

| Median (IQR) Biomarker Level Among PGD Cases | Median (IQR) Biomarker Level Among Controls | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Overall P Value | Gender-adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Overall P Value | |

| Leptin, ng/ml | ||||||||

| All (n = 120) | ||||||||

| Pretransplant | 10.9 (6.4–21.4) | 11.4 (4.8–19.7) | 1.3 (0.9–2) | 0.19 | 0.04 | 1.5 (1–2.3) | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| 6-h | 8.6 (4.2–21.1) | 5.7 (2.7–13.2) | 1.3 (1–1.6) | 0.052 | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 0.02 | ||

| 24-h | 23.4 (10–53.5) | 16.4 (7.6–37.2) | 1.5 (1–2.3) | 0.049 | 1.6 (1.1–2.3) | 0.03 | ||

| Without cardiopulmonary bypass (n = 74) | ||||||||

| Pretransplant | 12 (9.1–21.4) | 10 (4.4–17.2) | 1.9 (1.01–3.5) | 0.048 | 0.003 | 2.1 (1–4) | 0.04 | 0.002 |

| 6-h | 10.2 (5.6–38.4) | 5 (2.1–12.6) | 1.5 (1.1–2.2) | 0.02 | 1.9 (1.1–3.1) | 0.02 | ||

| 24-h | 33.9 (17.4–54.3) | 12.5 (6.9–32.2) | 2.2 (1.2–4.2) | 0.02 | 2.1 (1.2–3.9) | 0.02 | ||

| With cardiopulmonary bypass (n = 46) | ||||||||

| Pretransplant | 8.9 (5.9–19.6) | 18 (9–22.9) | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | 0.59 | 0.76 | 1 (0.6–1.9) | 0.88 | 0.73 |

| 6-h | 7.5 (3.5–10.9) | 8.4 (3.3–13.6) | 1 (0.7–1.4) | 0.96 | 1.3 (0.8–2.3) | 0.30 | ||

| 24-h | 23.3 (8.2–51.5) | 23.1 (10.3–38.1) | 1 (0.5–1.8) | 0.97 | 1.1 (0.6–2) | 0.69 | ||

| Adiponectin, mg/ml | ||||||||

| Pretransplant | 7.2 (4.6–11.5) | 8.8 (5.5–13.1) | 0.8 (0.4–1.6) | 0.49 | 0.60 | |||

| 6-h | 4.8 (3.3–7.2) | 5.8 (3.8–9.5) | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 0.10 | ||||

| 24-h | 4.8 (3.5–8.3) | 5.5 (3.5–9.8) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.66 | ||||

| Resistin, ng/ml | ||||||||

| Pretransplant | 8.3 (5.8–12.1) | 7.9 (5.6–12.5) | 1.2 (0.6–2.1) | 0.65 | 0.58 | |||

| 6-h | 21.1 (14–34.3) | 20.2 (14–31.5) | 1.1 (0.6–2) | 0.73 | ||||

| 24-h | 17.4 (13.4–26.5) | 16.1 (10.3–22.5) | 1.5 (0.8–2.7) | 0.18 | ||||

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; IQR = interquartile range.

Leptin (ng/ml), adiponectin (mg/ml), resistin (ng/ml) levels are median (interquartile range). Odds ratios are shown per natural log increase in biomarker levels. Unadjusted P value for the interaction between cardiopulmonary bypass and leptin level = 0.02. Overall P values are from generalized estimating equations.

Figure 2.

Box plots of plasma leptin and adiponectin levels in 40 cases with grade 3 primary graft dysfunction (PGD) (red) and 80 control subjects (white) before lung transplantation and 6 and 24 hours after reperfusion. (A) Plasma leptin (overall P = 0.04). (B) Plasma leptin stratified by sex (P for interaction = 0.97; sex-adjusted overall P = 0.02). (C) Plasma leptin stratified by cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) (P for interaction = 0.02; P value for leptin among those receiving cardiopulmonary bypass = 0.76; P value for leptin among those not receiving cardiopulmonary bypass = 0.003). (D) Plasma adiponectin (overall P = 0.60). Cntl = controls.

Figure 3.

Sex-adjusted continuous association between 24-hour plasma leptin level and primary graft dysfunction (PGD). Dark dotted line = effect estimate. Thin dashed lines = 95% confidence bands. The P value is for the association between plasma leptin and PGD.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that obesity and overweight are independent risk factors for PGD after lung transplantation. We also found that higher plasma leptin levels were associated with PGD. Both associations tended to be stronger among those who did not receive cardiopulmonary bypass. There were no significant associations between either plasma adiponectin or resistin levels and PGD.

Three previous studies have examined the association between obesity and ALI. Dossett and coworkers (40) found that obesity was associated with a lower risk of ALI among critically ill trauma patients. However, Gong and coworkers (9) and Anzueto and coworkers (10) both found that obesity increased the risk of ALI independent of ventilator settings in prospective cohorts of critically ill patients using strictly defined criteria. Our results extend these previous findings to lung transplant recipients and suggest that the increased risk of PGD might explain at least some of the higher mortality among obese lung transplant recipients (21).

We investigated possible mechanisms linking obesity and ALI, finding that higher plasma leptin levels were associated with a greater risk of PGD. Leptin, a 16-kD protein involved in the regulation of adipose tissue mass (41, 42), is known to have inflammatory effects, such as priming leukocytes to secrete proinflammatory cytokines (43, 44). The lung-specific effects of leptin, however, have only recently been examined. Bellmeyer and coworkers (13) found that exogenously administered leptin causes ALI in mice and that leptin resistance protects mice from hyperoxia-induced lung injury. Jain and coworkers (12) showed that leptin levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid are increased in patients with ALI, and that leptin promotes fibroproliferative ALI by increasing transforming growth factor-β1 transcription in a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ–dependent fashion (12), suggesting that leptin may not only promote ALI, but may contribute to lung fibrosis in response to injury, possibly shedding light on a mechanistic link between PGD and small airways fibrosis (obliterative bronchiolitis) after lung transplantation.

Although leptin-mediated lung inflammation is one possible mechanism of the association between obesity and PGD, our results do not provide definitive evidence to support this claim.

Other possible explanations for the link between obesity and PGD include the production of interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and other proinflammatory cytokines by macrophages recruited to hypertrophic and hypoxic adipose tissue (45), which should be explored in future, adequately powered studies. In addition, modulation of lung inflammation by other adipokines, such as resistin, adiponectin, visfatin (46–50), could be responsible. Although we did not specifically measure high-molecular-weight adiponectin (which may be the biologically relevant component) (51), our results do not support a role for adiponectin or resistin in the development of ALI after lung transplantation. Future studies of adiponectin and resistin in lung tissue or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and examination of the roles of other adipokines in the development of PGD should be pursued.

A prior study found that BMI was inversely associated with inflammatory markers in ALI (52), suggesting a role for noninflammatory mechanisms that link obesity and PGD. For example, obesity could lead to increased basilar atelectasis, mimicking the allograft infiltrates of PGD on chest radiographs. However, this is unlikely to explain the entirety of the observed association between obesity and PGD because our PGD definition was restricted to those with severely impaired gas exchange rather than radiographic changes alone. Obesity might also make thoracic surgery more complicated, with longer ischemic times and greater use of cardiopulmonary bypass, which could lead to PGD. However, our findings persisted after adjustment for these surgical factors.

Adipose tissue can produce proinflammatory cytokines in response to inflammation, possibly relegating our findings to simple epiphenomena (53). Although such “reverse causality” could explain our finding of higher leptin levels, it would not explain the higher risk of PGD among obese lung transplant recipients. In addition, if this were true, higher leptin levels would be expected among those who underwent cardiopulmonary bypass, a procedure that causes a systemic inflammatory response (54). Instead, our findings were strongest among those who did not undergo cardiopulmonary bypass. The proinflammatory effects of cardiopulmonary bypass on the lung may overwhelm and mask an effect of adipose tissue–mediated inflammation after lung transplantation.

Obesity is considered a relative contraindication to lung transplantation (55). Although our findings could be interpreted to support this position, we propose that obesity simply be one factor weighed among many when determining suitability for lung transplantation. Although our study did not examine the impact of weight loss, it remains prudent that pulmonologists encourage achievement of a healthy weight for all patients with lung disease, even in the absence of an urgent need for transplantation.

Our study has several limitations. There may have been error in the measurement of body weight and height, potentially misclassifying BMI for some study participants. Because measurement error is unlikely to differ by the risk of PGD, it would tend to bias the results toward the null; therefore, the associations between BMI and PGD may be even stronger than we have shown. We attempted to minimize residual and unmeasured confounding by using a flexible multivariable modeling approach, but such confounding may still have contributed to our results, including confounding by metabolic factors or kidney dysfunction (10). We restricted our cohort to those with COPD or ILD to minimize confounding by diagnosis. Our findings may not be applicable to those undergoing transplantation for other indications. Our small sample size for biomarker analyses did not allow for inclusion of multiple simultaneous covariates in a single model, limiting the interpretation of these exploratory analyses.

In conclusion, we found that obesity is an independent risk factor for PGD after lung transplantation and that higher plasma leptin levels were associated with a greater risk of PGD. Although weight reduction has not been shown to influence the risk of PGD or death after lung transplantation, our study should prompt clinicians to prioritize weight loss and maintenance of a healthy weight for lung transplant candidates. Future studies should focus on understanding and intervening on the mechanisms underlying this association.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants K23 HL086714 (D.J.L.), R01 HL086919 (J.D.C.), R01 HL087115 (J.D.C.), R01 HL088263 (L.B.W.), K24 HL103836 (L.B.W.); the Robert Wood Johnson Physician Faculty Scholars Program (D.J.L.); and the Herbert and Florence Irving Scholar Award (D.J.L.).

Author Contributions: D.J.L., S.M.K., C.W., S.M.A., and J.D.C. conceived and designed the study. D.J.L., S.M.K., N.W., C.W., S.B., S.M.P., J.L., J.M.D., K.M.W., A.W., V.N.L., M.C., J.B.O., J.R.S., S.M.A., L.B.W., and J.D.C. were involved in the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data and in writing or revising the article before submission.

Participants in the Lung Transplant Outcomes Group: David J. Lederer, M.D., M.S. (PI), Selim M. Arcasoy, M.D., Joshua R. Sonett, M.D., Jessie Wilt, M.D., Frank D'Ovidio, M.D., Matthew Bacchetta, M.D., Hilary Robbins, M.D., Nilani Ravichandran, N.P., Nadine Al-Naamani, M.D., Nisha Philip, M.B.B.S., Debbie Rybak, B.A., Shefali, Sanyal, B.S., Michael Koeckert, B.A., and Robert Sorabella, B.A., Columbia University; Jason Christie, M.D., M.S. (PI), Steven M. Kawut, M.D., M.S., Alberto Pocchetino, M.D., Y. Joseph Woo, M.D., Ejigayehu Demissie, M.S.N., Robert M. Kotloff, M.D., Vivek N. Ayha, M.D., James Lee, M.D., Denis Hadjiliadis, M.D., M.H.S., Melanie Doran, B.S., Richard Aplenc, M.D., Clifford Deutschman, M.D., M.S., and Benjamin Kohl, M.D, University of Pennsylvania (Coordinating site); Lorraine Ware, M.D. (PI), Pali Shah M.D., and Stephanie Logan, R.N., Vanderbilt University; Ann Weinacker, M.D. (PI), Ramona Doyle, M.D., Susan Spencer Jacobs, M.S.N., and Val Scott, M.S.N., Stanford University; Keith Wille, M.D. (PI), David McGiffin, M.D., and Necole Harris, B.S., University of Alabama, Birmingham; Jonathan Orens, M.D. (PI), Ashish Shah, M.D., and John McDyer, M.D., Johns Hopkins University; Vibha Lama, M.D., M.S. (PI), Fernando Martinez, M.D., M.S., and Emily Galopin, B.S., University of Michigan; Scott M. Palmer, M.D., M.H.S. (PI), David Zaas, M.D., M.B.A., R. Duane Davis, M.D., and Ashley Finlen-Copeland, M.S.W., Duke University; Sangeeta Bhorade, M.D. (PI), University of Chicago; and Maria Crespo, M.D. (PI), University of Pittsburgh.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0728OC on July 28, 2011

Author Disclosure: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Christie JD, Carby M, Bag R, Corris P, Hertz M, Weill D. Report of the ISHLT working group on primary lung graft dysfunction part II: Definition. A consensus statement of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2005;24:1454–1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christie JD, Kotloff RM, Ahya VN, Tino G, Pochettino A, Gaughan C, DeMissie E, Kimmel SE. The effect of primary graft dysfunction on survival after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:1312–1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daud SA, Yusen RD, Meyers BF, Chakinala MM, Walter MJ, Aloush AA, Patterson GA, Trulock EP, Hachem RR. Impact of immediate primary lung allograft dysfunction on bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:507–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitson BA, Prekker ME, Herrington CS, Whelan TP, Radosevich DM, Hertz MI, Dahlberg PS. Primary graft dysfunction and long-term pulmonary function after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2007;26:1004–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Perrot M, Fischer S, Liu M, Imai Y, Martins S, Sakiyama S, Tabata T, Bai XH, Waddell TK, Davidson BL, et al. Impact of human interleukin-10 on vector-induced inflammation and early graft function in rat lung transplantation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2003;28:616–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Perrot M, Sekine Y, Fischer S, Waddell TK, McRae K, Liu M, Wigle DA, Keshavjee S. Interleukin-8 release during early reperfusion predicts graft function in human lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:211–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serrick C, Adoumie R, Giaid A, Shennib H. The early release of interleukin-2, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma after ischemia reperfusion injury in the lung allograft. Transplantation 1994;58:1158–1162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mancuso P. Obesity and lung inflammation. J Appl Physiol 2010;108:722–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gong MN, Bajwa EK, Thompson BT, Christiani DC. Body mass index is associated with the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Thorax 2010;65:44–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anzueto A, Frutos-Vivar F, Esteban A, Bensalami N, Marks D, Raymondos K, Apezteguia C, Arabi Y, Hurtado J, Gonzalez M, et al. Influence of body mass index on outcome of the mechanically ventilated patients. Thorax 2011;66:66–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shibata R, Sato K, Pimentel DR, Takemura Y, Kihara S, Ohashi K, Funahashi T, Ouchi N, Walsh K. Adiponectin protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through AMPK- and COX-2-dependent mechanisms. Nat Med 2005;11:1096–1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain M, Budinger GS, Lo A, Urich D, Rivera SE, Ghosh AK, Gonzalez A, Chiarella SE, Marks K, Donnelly HK, et al. Leptin promotes fibroproliferative ARDS by inhibiting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:1490–1498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellmeyer A, Martino JM, Chandel NS, Scott Budinger GR, Dean DA, Mutlu GM. Leptin resistance protects mice from hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:587–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madill J, Gutierrez C, Grossman J, Allard J, Chan C, Hutcheon M, Keshavjee SH. Nutritional assessment of the lung transplant patient: body mass index as a predictor of 90-day mortality following transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2001;20:288–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanasky WF, Jr, Anton SD, Rodrigue JR, Perri MG, Szwed T, Baz MA. Impact of body weight on long-term survival after lung transplantation. Chest 2002;121:401–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Culver DA, Mazzone PJ, Khandwala F, Blazey HC, Decamp MM, Chapman JT. Discordant utility of ideal body weight and body mass index as predictors of mortality in lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant 2005;24:137–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hertz MI, Taylor DO, Trulock EP, Boucek MM, Mohacsi PJ, Edwards LB, Keck BM. The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: nineteenth official report—2002. J Heart Lung Transplant 2002;21:950–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trulock EP, Edwards LB, Taylor DO, Boucek MM, Keck BM, Hertz MI. Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twenty-second official adult lung and heart-lung transplant report–2005. J Heart Lung Transplant 2005;24:956–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trulock EP, Edwards LB, Taylor DO, Boucek MM, Keck BM, Hertz MI. Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twenty-third official adult lung and heart-lung transplantation report–2006. J Heart Lung Transplant 2006;25:880–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christie JD, Edwards LB, Aurora P, Dobbels F, Kirk R, Rahmel AO, Taylor DO, Kucheryavaya AY, Hertz MI. Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twenty-fifth official adult lung and heart/lung transplantation report–2008. J Heart Lung Transplant 2008;27:957–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lederer DJ, Wilt JS, D'Ovidio F, Bacchetta MD, Shah L, Ravichandran S, Lenoir J, Klein B, Sonett JR, Arcasoy SM. Obesity and underweight are associated with an increased risk of death after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:887–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Covarrubias M, Ware LB, Kawut SM, De Andrade J, Milstone A, Weinacker A, Orens J, Lama V, Wille K, Bellamy S, et al. Plasma intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and von Willebrand factor in primary graft dysfunction after lung transplantation. Am J Transplant 2007;7:2573–2578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sims MW, Beers MF, Ahya VN, Kawut SM, Sims KD, Lederer DJ, Palmer SM, Wille K, Lama V, Shah PD, et al. Effect of single versus bilateral lung transplantation on plasma surfactant protein D levels in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2011;140:489–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diamond JM, Kawut SM, Lederer DJ, Ahya VN, Kohl B, Sonett J, Palmer SM, Crespo M, Wille K, Lama VN, et al. Elevated plasma clara cell secretory protein concentration is associated with high-grade primary graft dysfunction. Am J Transplant 2011;11:561–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fang A, Studer S, Kawut SM, Ahya VN, Lee J, Wille K, Lama V, Ware L, Orens J, Weinacker A, et al. Elevated pulmonary artery pressure is a risk factor for primary graft dysfunction following lung transplantation for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2011;139:782–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christie JD, Shah CV, Kawut SM, Mangalmurti N, Lederer DJ, Sonett JR, Ahya VN, Palmer SM, Wille K, Lama V, et al. Plasma levels of receptor for advanced glycation end products, blood transfusion, and risk of primary graft dysfunction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:1010–1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawut SM, Okun J, Shimbo D, Lederer DJ, De Andrade J, Lama V, Shah A, Milstone A, Ware LB, Weinacker A, et al. Soluble P-selectin and the risk of primary graft dysfunction after lung transplantation. Chest 2009;136:237–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman SA, Wang L, Shah CV, Ahya VN, Pochettino A, Olthoff K, Shaked A, Wille K, Lama VN, Milstone A, et al. Plasma cytokines and chemokines in primary graft dysfunction post-lung transplantation. Am J Transplant 2009;9:389–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laara E. Study designs for biobank-based epidemiologic research on chronic diseases. Methods Mol Biol 2011;675:165–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization Expert Committee on Physical Status Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry: Report of a WHO expert committee. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christie JD, Bellamy S, Ware LB, Lederer D, Hadjiliadis D, Lee J, Robinson N, Localio AR, Wille K, Lama V, et al. Construct validity of the definition of primary graft dysfunction after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2010;29:1231–1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breslow NE, Clayton DG. Approximate inferences in generalized linear mixed models. J Am Stat Assoc 1993;88:9–25 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:702–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol 2005;162:199–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986;73:13–22 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hastie TJ, Tibshirani RJ. Generalized additive models. London: Chapman & Hall; 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Heijden GJ, Donders AR, Stijnen T, Moons KG. Imputation of missing values is superior to complete case analysis and the missing-indicator method in multivariable diagnostic research: a clinical example. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:1102–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubin DB, Schenker N. Multiple imputation in health-care databases: an overview and some applications. Stat Med 1991;10:585–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Havel PJ, Kasim-Karakas S, Dubuc GR, Mueller W, Phinney SD. Gender differences in plasma leptin concentrations. Nat Med 1996;2:949–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dossett LA, Heffernan D, Lightfoot M, Collier B, Diaz JJ, Sawyer RG, May AK. Obesity and pulmonary complications in critically injured adults. Chest 2008;134:974–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pelleymounter MA, Cullen MJ, Baker MB, Hecht R, Winters D, Boone T, Collins F. Effects of the obese gene product on body weight regulation in ob/ob mice. Science 1995;269:540–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature 1994;372:425–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gainsford T, Willson TA, Metcalf D, Handman E, McFarlane C, Ng A, Nicola NA, Alexander WS, Hilton DJ. Leptin can induce proliferation, differentiation, and functional activation of hemopoietic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93:14564–14568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Faggioni R, Jones-Carson J, Reed DA, Dinarello CA, Feingold KR, Grunfeld C, Fantuzzi G. Leptin-deficient (ob/ob) mice are protected from t cell-mediated hepatotoxicity: role of tumor necrosis factor alpha and IL-18. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:2367–2372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sethi JK, Vidal-Puig AJ. Adipose tissue function and plasticity orchestrate nutritional adaptation. J Lipid Res 2007;48:1253–1262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Medoff BD, Okamoto Y, Leyton P, Weng M, Sandall BP, Raher MJ, Kihara S, Bloch KD, Libby P, Luster AD. Adiponectin deficiency increases allergic airway inflammation and pulmonary vascular remodeling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2009;41:397–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Summer R, Little FF, Ouchi N, Takemura Y, Aprahamian T, Dwyer D, Fitzsimmons K, Suki B, Parameswaran H, Fine A, et al. Alveolar macrophage activation and an emphysema-like phenotype in adiponectin-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008;294:L1035–L1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bajwa EK, Yu CL, Gong MN, Thompson BT, Christiani DC. Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor gene polymorphisms and risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2007;35:1290–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hong SB, Huang Y, Moreno-Vinasco L, Sammani S, Moitra J, Barnard JW, Ma SF, Mirzapoiazova T, Evenoski C, Reeves RR, et al. Essential role of pre-B-cell colony enhancing factor in ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:605–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ye SQ, Simon BA, Maloney JP, Zambelli-Weiner A, Gao L, Grant A, Easley RB, McVerry BJ, Tuder RM, Standiford T, et al. Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor as a potential novel biomarker in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heidemann C, Sun Q, van Dam RM, Meigs JB, Zhang C, Tworoger SS, Mantzoros CS, Hu FB. Total and high-molecular-weight adiponectin and resistin in relation to the risk for type 2 diabetes in women. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:307–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stapleton RD, Dixon AE, Parsons PE, Ware LB, Suratt BT. The association between BMI and plasma cytokine levels in patients with acute lung injury. Chest 2010;138:568–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Faggioni R, Fantuzzi G, Fuller J, Dinarello CA, Feingold KR, Grunfeld C. IL-1 beta mediates leptin induction during inflammation. Am J Physiol 1998;274:R204–R208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Edmunds LH., Jr Inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;66:S12–S16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Orens JB, Estenne M, Arcasoy S, Conte JV, Corris P, Egan JJ, Egan T, Keshavjee S, Knoop C, Kotloff R, et al. International guidelines for the selection of lung transplant candidates: 2006 update–a consensus report from the Pulmonary Scientific Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2006;25:745–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]