Abstract

Rationale: Wounded alveolus resident cells are identified in human and experimental acute respiratory distress syndrome models. Poloxamer 188 (P188) is an amphiphilic macromolecule shown to have plasma membrane–sealing properties in various cell types.

Objectives: To investigate whether P188 (1) protects alveolus resident cells from necrosis and (2) is associated with reduced ventilator-induced lung injury in live rats, isolated perfused rat lungs, and scratch and stretch–wounded alveolar epithelial cells.

Methods: Seventy-four live rats and 18 isolated perfused rat lungs were ventilated with injurious or protective strategies while infused with P188 or control solution. Alveolar epithelial cell monolayers were subjected to scratch or stretch wounding in the presence or absence of P188.

Measurements and Main Results: P188 was associated with fewer mortally wounded alveolar cells in live rats and isolated perfused lungs. In vitro, P188 reduced the number of injured and necrotic cells, suggesting that P188 promotes cell repair and renders plasma membranes more resilient to deforming stress. The enhanced cell survival was accompanied by improvement in conventional measures of lung injury (peak airway pressure, wet-to-dry weight ratio) only in the ex vivo–perfused lung preparation and not in the live animal model.

Conclusions: P188 facilitates plasma membrane repair in alveolus resident cells, but has no salutary effects on lung mechanics or vascular barrier properties in live animals. This discordance may have pathophysiological significance for the interdependence of different injury mechanisms and therapeutic implications regarding the benefits of prolonging the life of stress-activated cells.

Keywords: mechanical ventilation, cell injury, poloxamer 188, cell repair, triblock copolymers

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) lungs are particularly susceptible to deforming stress from mechanical ventilation (ventilator-induced lung injury, VILI). Wounded alveolus resident cells are identified in human lungs with ARDS and experimental VILI models. Cellular deformation results in the activation of stress response genes, which elicit proinflammatory signals. Cell injury and repair, therefore, represent potential targets for lung protective interventions. Poloxamer 188 (P188) is an amphiphilic macromolecule shown to have plasma membrane–sealing properties in various cell types.

What This Study Adds to the Field

This study demonstrates that P188 facilitates the restoration of plasma membrane integrity and protects alveolus resident cells from stress-induced necrosis in multiple injury models. In vitro experiments suggest that P188 promotes cell repair and protects plasma membranes from injury. Reduced cell necrosis, however, had no salutary effects on lung mechanics or vascular barrier properties in the complex system of the live animal. This finding raises a question concerning whether it is physiologically advantageous for wounded cells to succumb quickly rather than to repair at the cost of prolonged stress signaling and enhanced immunological responses.

Although the injurious potential of mechanical ventilation was first described five decades ago (1), the pathophysiology of ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) remains a subject of debate. VILI is often discussed in the context of acute lung injury (ALI) and the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), because injured lungs are particularly susceptible to deforming stress on account of alveolar overdistension and cyclic “opening and collapse” of unstable lung units (2). The clinical manifestations of VILI are indistinguishable from all-cause ALI and reflect altered capillary barrier properties, alveolar inflammation, fibroproliferation, and microvascular coagulopathy (3). In aggregate these alterations are frequently referred to as “biotrauma” in distinction to barotrauma, which describes one specific manifestation of pulmonary stress failure, namely, extraalveolar air (4).

The pathogenesis of biotrauma involves a spectrum of cellular mechanotransduction events resulting in the activation of stress-response genes, which elicit proinflammatory signals. For example, alveolar epithelial monolayers subjected to stretch release proinflammatory cytokines (5, 6). Lower stretch levels can induce a mechanotransductive response without causing nanoscale plasma membrane lesions, but this response is greatly amplified when strain amplitudes that result in plasma membrane disruption are employed. Wounded alveolus resident cells can be identified in experimental VILI models (7, 8) and have been observed in autopsy specimens of human lungs with ARDS (9). It thus stands to reason that cell injury and repair contribute to the pathogenesis of VILI and as such represent a potential target for lung-protective interventions.

Poloxamer 188 or Pluronic F-68 (P188; molecular weight 8,400) belongs to a family of surface-active amphiphilic macromolecules consisting of a central polyoxypropylene molecule flanked by two hydrophilic chains of polyoxyethylene (10, 11). These surfactants were introduced in the 1950s (BASF, Mount Olive, NJ) and P188 was one of the first to become commercially available. It has since found clinical applications as a skin wound cleaner, an antithrombotic, a rheological agent in sickle cell disease, and an emulsifying agent in artificial blood (10, 12–15). Most importantly, it has been shown to have plasma membrane–sealing properties and to enhance the repair of skeletal muscle cells, cardiac myocytes, neurons, fibroblasts, and corneal endothelial cells after a variety of insults (16–25). It is postulated that P188 incorporates into lipid bilayers, either strengthening the plasma membrane against wounding or “patching” injured cells and thus saving them from death.

We investigated whether P188 (1) restores the integrity of plasma membranes and protects alveolus resident cells from necrosis and (2) is associated with reduced ventilator-induced lung injury as assessed by physiological, molecular, and histopathological surrogate markers in three models: (1) live rats, (2) isolated perfused rat lungs, and (3) scratch and stretch–wounded alveolar epithelial cells. Some of the results of this study have been reported in abstract form (26, 27).

Methods

Live Animal Model

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN). Female Sprague-Dawley rats were randomized into four groups ventilated (flexiVent; SCIREQ, Montreal, PQ, Canada) for 4 hours: (1) P188–tidal volume (Vt) 40 ml/kg (n = 28), (2) saline–Vt 40 ml/kg (n = 28), (3) P188–Vt 6 ml/kg (n = 9), and (4) saline–Vt 6 ml/kg (n = 9). Animals in P188 groups received an intravenous bolus (300 mg/kg) of P188 (Pluronic F-68; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) followed by a continuous infusion (30 mg/kg/h). Animals in the placebo groups received an equal volume of saline.

Isolated Perfused Rat Lung Preparation

Lungs were prepared as described in the online supplement. Eighteen lungs were ventilated for 40 minutes and randomized to two groups perfused with (1) P188-containing solution (1 mg/ml) (n = 9) and (2) Krebs without P188 (n = 9).

Laser Confocal Microscopy–based Assessment of Cell Wounding in Intact Lungs

Fluorescent label propidium iodide (PI) (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) was administered intravenously 30 minutes before the end of mechanical ventilation in live animals and was added to the perfusate 10 minutes after the start of injurious ventilation in the isolated perfused lungs. The degree of cell membrane injury was expressed as a ratio of the number of PI-positive cells per total number of alveoli in the field from eight random subpleural images (cell injury index).

Microvascular Permeability to Albumin and Analysis of Lung Water

Extravasation of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–albumin into the alveoli was used as a quantitative measure of changes in microvascular protein permeability. FITC–albumin (#A9771; Sigma-Aldrich) was injected intravenously in the live animal model and added to the perfusate in the isolated perfused lungs. Intraalveolar green intensity was quantified by confocal microscopy. Laser excitation power and exposure time were held constant in all experiments. Lung wet-to-dry (W/D) weight ratio was used as an index of pulmonary edema formation.

Bronchoalveolar Lavage

The left lung was lavaged and bronchoalveolar (BAL) fluid was analyzed for total cell number and differential cell count, protein content (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity (Roche, Indianapolis, IN).

Multiplex ELISA of Plasma and BAL Fluid Cytokines

Plasma and BAL fluid concentrations of the following cytokines were measured with a multiplex ELISA kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA): IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC), macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-2, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES).

Light Microscopy and TUNEL Analysis

Lung, liver, and kidney tissues were removed for histology. In paraffin-fixed liver and kidney tissues, cells were assayed for apoptosis by terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase–mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL), using the ApopTag peroxidase in situ apoptosis detection kit (Millipore, Temecula, CA).

Cell Monolayer Stretch and Scratch Injury

A549 cell monolayers were preincubated in medium with or without P188 (1 mg/ml) before scratch wounding. Injured cells were allowed to reseal for 2 minutes before PI was added. Epifluorescence images from scratch margins were obtained. PI nuclear labeling was interpreted as failure of membrane repair and predictor of cell death by necrosis. The percentage of necrotic cells at the scratch margins is reported.

Alveolar epithelial type 2 (AT2) cells were grown to confluence in 6-well plates (28) and preincubated in medium with or without P188 (1 mg/ml). Fluorescent dextran (FDx, 2.5 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) was added and monolayers were then exposed to repetitive cycles of 10% strain (29). Cells were allowed to repair for 2 minutes, and then washed and incubated with PI-containing medium. Cells with green cytoplasmic dextran fluorescence were considered wounded but healed, whereas cells with red PI fluorescent nuclei were considered wounded but permanently injured, that is, necrotic (30, 31). The percentage of wounded and repaired cells is reported.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as means ± the standard deviation (SD) or standard error (SE), where indicated. Data were assessed for significance by Student t test or analysis of variance (GraphPad Prism ver sion 5; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Additional details on all methods are provided in the online supplement.

Results

Live Animal Model

Physiological data.

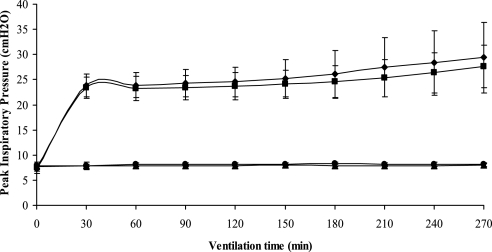

Peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) significantly increased in rats ventilated with high Vt after 4 hours of mechanical ventilation (saline, P < 0.05; P188, P < 0.05), but there was no significant difference between P188 and saline groups (Figure 1 and Table 1). There was no increase in PIP in the low-Vt groups, nor was there a difference between the interventions (P188 vs. saline). The lung W/D ratio was higher in animals receiving injurious versus protective ventilation. There was no significant difference in lung W/D ratio between P188 and saline. pH and Po2 were significantly lower and Pco2 was higher in animals receiving high Vt (P < 0.05), but values were similar between those infused with P188 and saline. There was no difference in mean arterial pressure and hematocrit at the end of mechanical ventilation, fluid input, or urine output in any of the groups.

Figure 1.

Peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) (mean ± SD) during injurious (tidal volume [Vt], 40 ml/kg) or protective (Vt, 6 ml/kg) ventilation in animals receiving normal saline or poloxamer 188 (P188). During the first 30 minutes all rats were ventilated at a Vt of 6 ml/kg. PIP significantly increased in rats ventilated at a Vt of 40 ml/kg, but there was no statistically significant difference between P188 and saline groups. Triangles, Vt 6 ml/kg–saline (n = 6); circles, Vt 6 ml/kg–P188 (n = 6); diamonds, Vt 40 ml/kg–saline (n = 16); squares, Vt 40 ml/kg–P188 (n = 16).

TABLE 1.

EXPERIMENTAL CONDITIONS AT BEGINNING AND END OF VENTILATION IN LIVE RATS

| Vt 6 ml/kg–Saline | Vt 6 ml/kg–P188 | Vt 40 ml/kg–Saline | Vt 40 ml/kg–P188 | |

| (n = 6) | (n = 6) | (n = 16) | (n = 16) | |

| PIP, cm H2O | ||||

| Start | 8 ± 0.50 | 8 ± 0.50 | 24 ± 2*† | 23 ± 2*† |

| End | 8 ± 0.40 | 8 ± 0.30 | 29 ± 7*†‡ | 28 ± 4*†‡ |

| ΔPIP, cm H2O | 0.0 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 5.6 ± 5.7*† | 4.3 ± 2.9*† |

| W/D ratio | 5.7 ± 0.5 | 5.9 ± 0.7 | 7.4 ± 3.5* | 7.4 ± 1.1*† |

| pH | 7.34 ± 0.05 | 7.37 ± 0.04 | 7.28 + 0.03† | 7.25 ± 0.05*† |

| PaO2, mm Hg | 556 ± 75.8 | 573 ± 73.5 | 450.1 ± 53.6*† | 461.8 ± 62.3† |

| PaCO2, mm Hg | 42 ± 5 | 40 ± 6 | 51 ± 4*† | 51 ± 4*† |

| HCO3, mmol/L | 22.5 ± 2.4 | 22.9 ± 2.0 | 23.7 ± 1.4 | 22.0 ± 2.1 |

| MAP, mm Hg | ||||

| Start | 104 ± 23 | 89 ± 14 | 96 ± 25 | 123 ± 24†§ |

| End | 108 ± 35 | 112 ± 19 | 98 ± 33 | 116 ± 33 |

| Hematocrit, % | 39.3 ± 3.4 | 37.5 ± 5.2 | 36.7 ± 2.2 | 37.3 ± 3.5 |

| Fluid input, ml/g | 0.027 ± 0.00 | 0.028 ± 0.00 | 0.025 ± 0.02 | 0.025 ± 0.01 |

| Urine output, ml/g | 0.022 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.025 ± 0.02 | 0.024 ± 0.01 |

Definition of abbreviations: MAP = mean arterial pressure; P188 = poloxamer 188; PIP = peak inspiratory pressure; ΔPIP = change in peak inspiratory pressure; Vt = tidal volume; W/D = lung wet-to-dry weight ratio.

Note: Arterial blood gases were measured in 16 animals of the high-Vt groups (P188, n = 8; saline, n = 8) and 12 animals of the low-Vt groups.

P < 0.05 versus Vt 6 ml/kg–saline.

P < 0.05 versus Vt 6 ml/kg–P188.

P < 0.05 versus starting PIP.

P < 0.05 versus Vt 40 ml/kg–saline.

Lung injury.

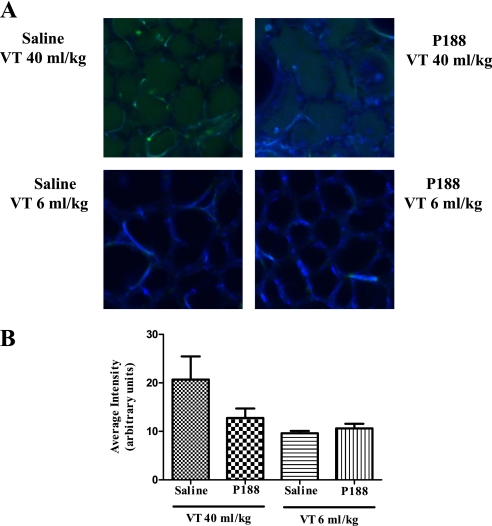

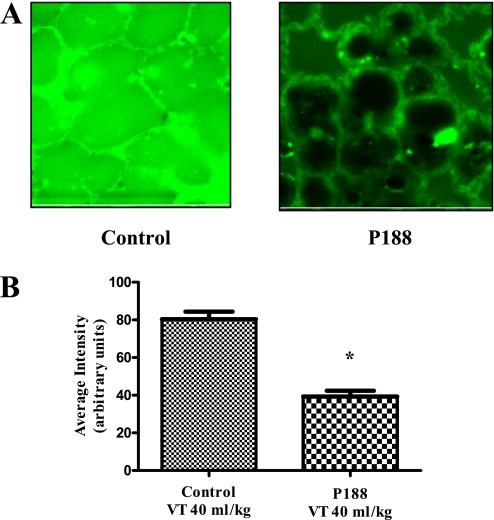

Intraalveolar leak of FITC–albumin was used to measure the effects of mechanical ventilation on microvascular protein permeability. Although P188 infusion was associated with lower intraalveolar FITC–albumin concentrations in rats receiving Vt 40 ml/kg, differences between groups did not achieve statistical significance (Vt 40 ml/kg–saline, 20.7 ± 19.1; Vt 40 ml/kg–P188, 12.8 ± 7.8; Vt 6 ml/kg–saline, 9.6 ± 1.1; Vt 6 ml/kg–P188, 10.6 ± 2.1; arbitrary units) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(A) Confocal images of subpleural alveoli of lungs excised from live rats (top left, tidal volume [Vt] 40 ml/kg–saline; top right, Vt 40 ml/kg–poloxamer 188 [P188]; bottom left, Vt 6 ml/kg–saline; bottom right, Vt 6 ml/kg–P188). Green fluorescence marks fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated albumin that has leaked in the intraalveolar space. Autofluorescence is shown in blue. (B) Average intensity (±SEM) of intraalveolar green fluorescence (arbitrary units) as assessed from eight random subpleural fields (P188–Vt 40 ml/kg, n = 16; saline–Vt 40 ml/kg, n = 16; P188–Vt 6 ml/kg, n = 6; and saline–Vt 6 ml/kg, n = 6). Although P188 infusion was associated with lower intraalveolar intensities in rats receiving Vt 40 ml/kg, differences between groups did not achieve statistical significance.

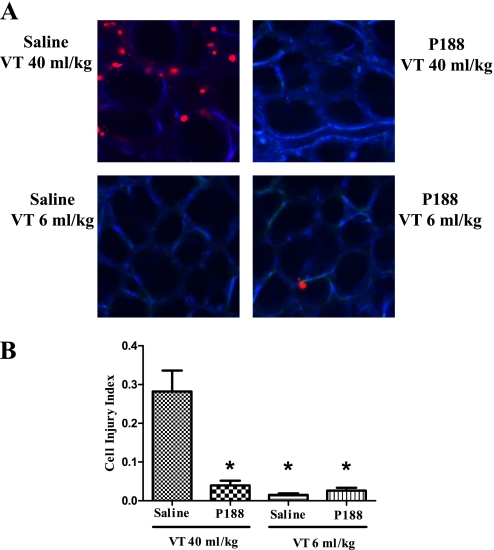

Animals ventilated with Vt 6 ml/kg had few injured alveolar cells (injury index: saline, 0.015 ± 0.013; P188, 0.026 ± 0.017 cells per alveolus) (Figure 3). In contrast, mechanical ventilation at Vt 40 ml/kg was associated with a significant increase in the number of PI-positive cells in saline-treated animals (saline, 0.202 ± 0.116 cells per alveolus; P < 0.05). P188 prevented this increase (0.048 ± 0.056 cells per alveolus; P < 0.001 vs. saline), so that there was no significant difference in the injury index between low-Vt controls and high-Vt rats infused with P188.

Figure 3.

(A) Confocal images of subpleural alveoli of lungs excised from live rats (top left, tidal volume [Vt] 40 ml/kg–saline; top right, Vt 40 ml/kg–poloxamer 188 [P188]; bottom left, Vt 6 ml/kg–saline; bottom right, Vt 6 ml/kg–P188). The red nuclei mark injured cells (propidium iodide [PI]–positive nuclei). Autofluorescence is shown in blue. (B) Average number (±SEM) of PI-positive cells per alveolus as assessed from eight random subpleural fields (P188–Vt 40 ml/kg, n = 16; saline–Vt 40 ml/kg, n = 16; P188–Vt 6 ml/kg, n = 6; and saline–Vt 6 ml/kg, n = 6). Although mechanical ventilation at Vt 40 ml/kg was associated with a significant increase in the number of PI-positive cells in saline-treated animals, there was no significant difference in the injury index between low-Vt controls and high-Vt rats infused with P188. (*P < 0.05 vs. Vt 40 ml/kg–saline)

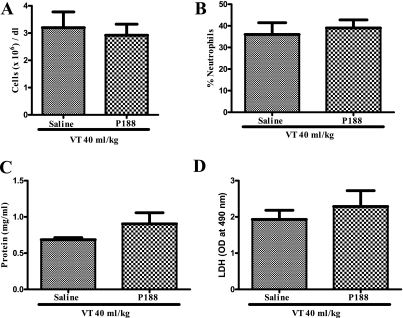

BAL in animals ventilated at injurious Vt yielded similar recovery rates in saline and P188 groups. BAL fluid neutrophilia was noted in both groups (Vt 40 ml/kg–saline, 36 ± 13.3%; Vt 40 ml/kg–P188, 39 ± 9.3%) and there was no significant difference in total number of cells, protein content, LDH activity, and levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, KC, MIP-2, TNF- α, and RANTES between P188- and saline-treated animals (Figure 4 and Table 2).

Figure 4.

(A) Total cell counts, (B) percentage of neutrophils, (C) protein content, and (D) lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of live rats ventilated at 40 ml/kg and infused with either saline (n = 6) or poloxamer 188 (P188) (n = 6). Neutrophilia was noted in both groups and there was no significant difference in total number of cells, protein content, or LDH activity. OD = optical density.

TABLE 2.

BRONCHOALVEOLAR LAVAGE FLUID CONCENTRATIONS OF CYTOKINES IN LIVE RATS VENTILATED AT INJURIOUS SETTINGS WHILE INFUSED WITH P188 OR SALINE

| Saline–Vt 40 ml/kg | P188–Vt 40 ml/kg | |

| (n = 6) | (n = 6) | |

| IL-1β | 17.2 ± 3.2 | 24.4 ± 19.8 |

| IL-6 | 32.3 ± 10.9 | 29.9 ± 10.5 |

| TNF-α | 11.1 ± 7.9 | 7.6 ± 5.4 |

| IL-10 | OOR < | OOR < |

| KC | 128.1 ± 35.6 | 179.3 ± 101 |

| RANTES | OOR < | OOR < |

| MIP-2 | 155.8 ± 80.3 | 146.9 ± 67.2 |

Definition of abbreviations: KC = keratinocyte-derived chemokine; MIP-2 = macrophage inflammatory protein-2; OOR < = out of range below; RANTES = regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted; TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor-α; Vt = tidal volume.

Note: Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid concentrations of cytokines are expressed as picograms per milliliter.

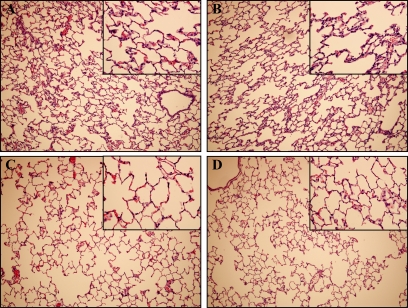

Injurious ventilation caused moderate histopathological changes, including mildly thickened alveolar walls, rare neutrophils and red blood cells in alveolar spaces, and areas of atelectasis. No difference was noted between animals treated with saline and P188 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Injurious mechanical ventilation was associated with mildly thickened alveolar walls, rare red blood cells in alveolar spaces, and areas of atelectasis on histopathology. Shown are representative photomicrographs (original magnification, ×100; insets, ×400) with hematoxylin and eosin staining of lung sections after 4 hours of injurious and control mechanical ventilation: (A) poloxamer 188 (P188)–tidal volume (Vt) 40 ml/kg (n = 6), (B) saline–Vt 40 ml/kg (n = 6), (C) P188–Vt 6 ml/kg (n = 3), and (D) saline–Vt 6 ml/kg (n = 3).

Histology and TUNEL of distant organs.

Liver and kidney tissue samples were examined from rats ventilated at Vt 40 ml/kg (saline, n = 8; P188, n = 8). Only mild congestion was noted on hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides of both organs. There was no difference between animals receiving saline and those infused with P188. Few TUNEL-positive cells were observed in the liver or kidney in both groups.

Circulating cytokines.

Plasma concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, MIP-2, and RANTES were below detectable levels in most or all of the animals. There was no significant difference in the levels of KC and TNF-α between groups (see Table E3 in the online supplement).

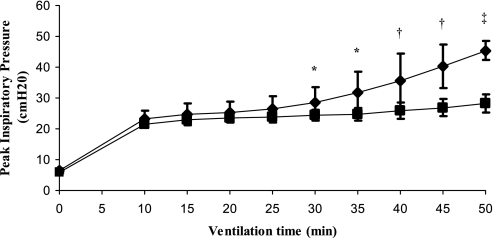

Isolated Perfused Lungs

Injurious ventilation caused an increase in PIP in both groups (P < 0.001). The change in PIP was significantly lower when P188 was added to the perfusate (P < 0.001) (Figure 6 and Table 3). The difference between the two groups became significant after 20 minutes of high-Vt ventilation. The lung W/D ratio was also significantly lower in the P188 group (P < 0.001). Pulmonary artery pressures were similar in the two groups.

Figure 6.

Peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) (mean ± SD) during high tidal volume (Vt 40 ml/kg) ventilation in isolated lungs perfused with Krebs with or without poloxamer 188 (P188). During the first 10 minutes all lungs were ventilated at a Vt of 6 ml/kg. The change in PIP was significantly lower when P188 was added to the perfusate. The difference between the two groups became significant after 20 minutes of high-Vt ventilation. (*P < 0.05, †P < 0.01, ‡P < 0.001). Diamonds, Vt 40 ml/kg–Krebs without P188 (n = 9); squares, Vt 40 ml/kg–Krebs with P188 (n = 9).

TABLE 3.

EXPERIMENTAL CONDITIONS AT BEGINNING AND END OF VENTILATION IN ISOLATED PERFUSED LUNGS

| Vt 40 ml/kg–Krebs | Vt 40 ml/kg–P188 | |

| (n = 9) | (n = 9) | |

| PIP, cm H2O | ||

| Start | 23.3 ± 2.6 | 21.5 ± 0.9 |

| End | 45.4 ± 3.2* | 28.3 ± 2.9* |

| ΔPIP, cm H2O | 22.1 ± 3.8† | 6.8 ± 2.4 |

| W/D ratio | 17.5 ± 4.3† | 9.0 ± 2.0 |

| PAP, cm H2O | ||

| Start | 7.7 ± 2.4 | 6.2 ± 0.8 |

| End | 12.4 ± 6.7 | 10.6 ± 4.9 |

| ΔPAP, cm H2O | 4.8 ± 4.9 | 4.3 ± 4.5 |

Definition of abbreviations: PAP = pulmonary arterial pressure; ΔPAP = change in pulmonary artery pressure; PIP = peak inspiratory pressure; ΔPIP = change in peak inspiratory pressure; Vt = tidal volume; W/D = lung wet-to-dry weight ratio.

P < 0.001 versus starting PIP.

P < 0.001 versus Vt 40 ml/kg–P188.

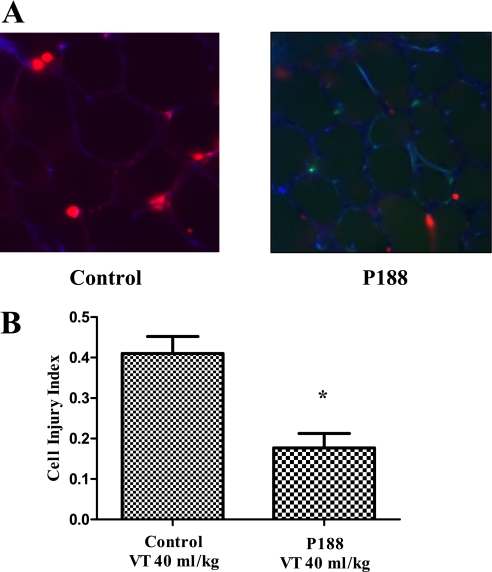

Protein microvascular permeability was significantly less in the group treated with P188 (39.3 ± 9 vs. 80.4 ± 12 arbitrary units; P < 0.001) (Figure 7). High-Vt ventilation caused cellular injury, as evidenced by the PI-positive cells in the fluorescence images. The number of PI-positive cells per alveolus was significantly lower in the presence of P188 (0.18 ± 0.11 vs. 0.41 ± 0.13 in Krebs; P = 0.0012) (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

(A) Confocal images of subpleural alveoli (right, Krebs with poloxamer 188 [P188]; left, Krebs without P188) in isolated perfused lungs ventilated at a tidal volume (Vt) of 40 ml/kg. Green fluorescence marks fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated albumin that has leaked into the intraalveolar space. (B) Average intensity (±SEM) of intraalveolar green fluorescence (arbitrary units) as assessed from eight random subpleural fields (Vt 40 ml/kg–Krebs without P188, n = 9; Vt 40 ml/kg–Krebs with P188, n = 9). Protein microvascular permeability was significantly less in the group infused with P188 (*P < 0.001).

Figure 8.

(A) Confocal images of subpleural alveoli (right, Krebs with poloxamer 188 [P188]; left, Krebs without P188) in isolated perfused lungs ventilated at a tidal volume (Vt) of 40 ml/kg. The red nuclei mark injured cells (propidium iodide [PI]–positive nuclei). Autofluorescence is shown in blue. (B) Average number (±SEM) of PI-positive cells per alveolus as assessed from eight random subpleural fields (Vt 40 ml/kg–Krebs without P188, n = 9; Vt 40 ml/kg–Krebs with P188, n = 9). The number of PI-positive cells per alveolus was significantly lower in the presence of P188 (*P = 0.0012).

Cell Monolayer Wounding and Repair

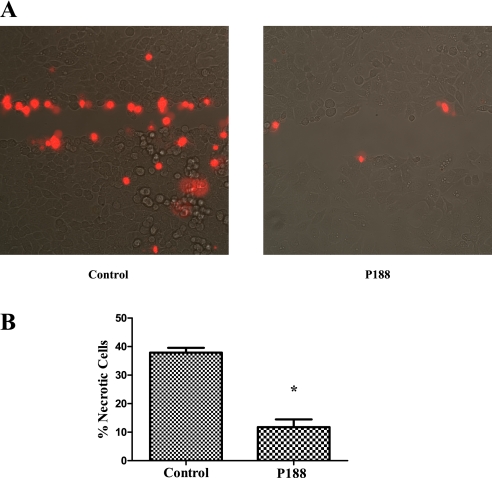

Figure 9 shows two representative fluorescence images of scratch-injured alveolar epithelial monolayers. PI was added 2 minutes after the scratch injury and therefore PI-positive cells are cells that were wounded but did not repair and were therefore considered necrotic. When scratched in the presence of P188, the percentage of necrotic cells was significantly less (11.8 ± 6.0 vs. 37.9 ± 4.1% in the absence of P188; P < 0.05).

Figure 9.

(A) Confocal images of cells scratched in the presence or absence of poloxamer 188 (P188). The red nuclei mark necrotic cells, that is, cells that were injured and did not repair (propidium iodide [PI]–positive nuclei). (B) Average number (±SEM) of PI-positive cells per number of all cells on the scratch line when the label was applied after cells were allowed to repair (n = 6 experiments under each condition). When scratched in the presence of P188, the percentage of necrotic cells was significantly less (*P = 0.0022).

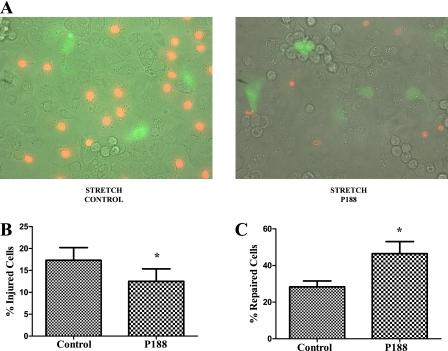

When alveolar epithelial type 2 cells were stretched in the presence of FDx, the percentage of injured fluorescently labeled cells (FDx and PI) was less in the P188-treated samples (12.5 ± 6.9 vs. 17.3 ± 7.0%; P < 0.05) (Figure 10). The percentage of FDx-labeled cells relative to the total number of labeled cells was significantly higher in the P188 group, indicating that more cells repair when P188 is present (46.5 ± 16.1 vs. 28.4 ± 7.9%; P < 0.05) (Figure 10). This observation suggests that P188 not only enhances cell repair, but also increases cellular resistance to plasma membrane injury.

Figure 10.

(A) Confocal images of cells stretched in the presence or absence of poloxamer 188 (P188). Cells with green cytoplasmic dextran fluorescence were considered wounded but healed, whereas cells with red propidium iodide fluorescent nuclei were considered wounded but permanently injured, that is, necrotic. (B) Average number (±SEM) of injured cells per field. (C) Average number (±SEM) of repaired cells per field (n = 6 plates).

Discussion

We present evidence in several models of mechanical stress–induced lung injury that the administration of the amphiphilic macromolecule P188 is associated with fewer mortally wounded alveolar cells. In each of the three VILI models examined the results are consistent with the postulated P188 effect, namely, facilitated plasma membrane wound repair. Cell stretch and monolayer scratch experiments suggest that P188 promotes cell repair and protects plasma membranes from stress failure. Whereas in the isolated perfused lung preparation enhanced cell repair was accompanied by improved physiological surrogates of injury, this was not the case in the live animal model. Therefore, we could clearly demonstrate the anticipated P188 effect, but not its preclinical efficacy. The implications of this finding with respect to cell repair–targeted therapeutic interventions are discussed.

Physical disruption of alveolar cells has been described in autopsy specimens of human lungs with ARDS and experimental VILI models (7–9, 32, 33). Our group has previously validated a method for quantifying cell wounding using PI in a rat model of VILI (8) and cell injury and repair using PI and FDx in stretched epithelial monolayers (30). PI is a membrane-impermeable label and the method identifies cells with plasma membrane stress failure. Cells that are injured in the presence of FDx exhibit a cytoplasmic green stain that becomes trapped in the cell if plasma membrane breaks reseal or leaks out if the cells are unable to repair. In the present study in both the live rat and isolated perfused lung models the cell injury index was significantly lower when P188 was infused. In vitro, P188 reduced the number of injured and necrotic cells, suggesting that P188 promotes cell repair and renders plasma membranes more resilient to deforming stress.

P188 belongs to a family of water-soluble surfactants. This amphiphilic, triblock copolymer is composed of a central block of 30 hydrophobic polypropylene oxide moieties and two peripheral blocks of 75 hydrophilic polyethylene oxide moieties each (15). P188 has been shown to reduce loss of intracellular contents and thus resultant cellular necrosis in skeletal muscle cells, cardiac myocytes, neurons, fibroblasts, and corneal endothelial cells after thermal, electrical, radiation, oxidative, and toxic injury (16–25). The protective effects of P188 are attributed to its membrane-sealing properties. P188 incorporates into lipid bilayers, but it is not yet clear whether it interacts only with the disrupted parts of the membrane to seal the lesions or whether its integration and interaction with the entire bilayer alter membrane properties in a way that renders it more resistant to injury or facilitates its repair (smaller lesions that close faster) (16, 18, 22, 34). Early experiments showed that interaction of P188 with lipid monolayers and bilayers depends on the initial state of the layer and the concentration of poloxamer in solution (22, 35, 36). If the lipid molecules of the layer are loosely packed and average intermolecular distances are large, poloxamer may be easily incorporated into the membrane. If the layer is in a condensed state, poloxamer molecules may be excluded from the layer, but favorable interactions between the lipid head groups and the ethylene oxide groups of the poloxamer may lead to the formation of an associated layer in the subphase adjacent to the solution-facing surfaces of the membrane. This layer would increase the effective membrane thickness and strengthen the membrane against injury (22).

Several adverse reactions have been reported with P188 infusion. Headache, nausea, and back and leg pain have been reported in humans enrolled in pharmacokinetic studies (15, 37, 38). P188 was used as an emulsifying agent in perfluorocarbon artificial blood, but its use was abandoned because of a high rate of adverse reactions including hypotension, hypoxemia, pulmonary hypertension, and neutropenia (39–41). These effects were attributed to the ability of P188 to activate the alternate complement pathway leading to mediator release, demargination and aggregation of white blood cells, pulmonary leukostasis, and hypoxemia (42, 43). Intravenous administration of P188 in dogs caused a transient increase in pulmonary resistance and no long-lasting effect on pulmonary mechanics and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (44). P188 infusion reduced the duration of acute chest syndrome and vasoocclusive crisis in patients with sickle cell disease (45, 46). It improved microvascular blood flow by reducing blood viscosity and adhesive frictional forces and was found to reverse diminished venular diameter and red cell velocity in these patients (47). The drug was safe and well tolerated in sickle cell disease studies that used doses similar to those we used in rats (12). We did not notice any acute or sustained reactions in live animals treated with P188 in terms of vital signs, hypoxemia, and peak airway pressure, other than a transient increase in mean arterial pressure after the bolus infusion, and no meaningful difference in the measured cytokines.

In the isolated perfused lung model the lower cell injury index with injurious ventilation in the presence of P188 was accompanied by milder derangements in pulmonary mechanics and milder impairment of lung barrier function. In the live animal model, however, this association between P188-facilitated cell repair with other markers of lung injury was lost. Despite the significantly lower cell injury index in the P188-treated animals, PIP significantly increased with injurious ventilation in both P188 and saline groups, and lung W/D weight ratio and Pco2 were higher and Po2 was lower in both groups compared with animals ventilated at protective settings. FITC–albumin intensity, which was measured in the intraalveolar space, was low in all groups even though the W/D lung weight ratio was higher with injurious ventilation. Although paradoxical at first glance, this discordance may either reflect differences in edema distributions between alveolus and interstitium or point to increased vascular permeability for water but not for albumin. The different behavior of the blood-free isolated perfused lungs compared with the lungs exposed to the more complicated milieu and the systemic immune responses of the live animal is not surprising.

The lack of improvement in conventional measures of lung injury despite the reduction in fatal cell injury is intriguing. Different surrogate markers such as pulmonary mechanics, edema, inflammatory markers, and number of wounded cells represent different aspects of injury. Although they may influence or trigger each other and act synergistically, they could also be manifestations of different injury pathways or different stages of the same response (8, 48). Cytoskeletal remodeling of endothelial cells, which can be triggered without cell necrosis, can influence vascular permeability (49–51). Increases in lung impedance and lung water have been described in the absence of increases in proinflammatory cytokines (52).

The fact that in the live animal model enhanced repair of injured cells does not prevent the expression of physiological and immunological surrogates of injury raises a question concerning whether it is advantageous for wounded cells to succumb quickly rather than to repair at the cost of prolonged stress signaling. Efficient clearance of apoptotic and necrotic cells is essential for the modulation of inflammation and immune responses (53). There is extensive literature showing that deformation of alveolar cells, even in the absence of membrane breaks, can activate several inter- and intracellular pathways affecting intra- and extracellular remodeling, cytokine production, ion channel regulation, and surfactant homeostasis (54, 55). Salvation and preservation of activated cells could lead by virtue of cell contact and paracrine interactions with noninjured neighbors to an orchestrated amplified response (56). Indirect evidence is in favor of this hypothesis. Hypercapnic acidosis, for example, impairs plasma membrane wound resealing in ventilator-injured lungs (30), but at the same time exerts antiinflammatory and immunomodulatory effects and attenuates acute lung injury including VILI (57, 58). Similarly, purinergic receptor stimulation on airway epithelial cells leads to activation of dual oxidase-1, which enhances epithelial wound repair (59), but also mediates the release of proinflammatory mediators (60). Even though the above observations do not prove causality between impaired repair and reduced inflammation and vice versa, they can form the basis of an intriguing hypothesis, namely, that salvation of stressed cells is detrimental. at least in the short term.

This study has several limitations, including those of employing an animal model to study a human disease. A major caveat is that short-term experiments in laboratory preparations are not suitable to test mechanisms and interventions that may take days to evolve. Four hours of mechanical ventilation may be too short a period to manifest the full-blown injury syndrome and, therefore, for example, no interpretable signal in circulating cytokine expression could be found. Moreover we were not able to differentiate between the specific alveolar cell types that that experienced plasma membrane lesions.

We have demonstrated that P188 facilitates the restoration of plasma membrane integrity and protects alveolus resident cells from stress-induced necrosis. Although this effect is preserved across different injury models, facilitating cell repair had no salutary effects on lung mechanics or vascular barrier properties in the more complex system of the live animal. This discordance among different aspects of ventilator-induced lung injury may have pathophysiological significance for the interdependence of various injury mechanisms and therapeutic implications regarding the benefits of prolonging the life of stress-activated cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Dragan Jevremovic for valuable assistance in histopathological evaluation.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Conception, hypotheses delineation and design: M.P., R.D.H.; acquisition of data: Y.D.L., D.L.R., M.P.; analysis and interpretation of data: M.P., Y.D.L., D.L.R., R.D.H.; drafting the article: M.P., R.D.H.; final approval of the version to be published: R.D.H.

Supported by NIH grant HL63178.

This article has an online supplement, which is available from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0647OC on June 21, 2011

Author Disclosure: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Greenfield LJ, Ebert PA, Benson DW. Effect of positive pressure ventilation on surface tension properties of lung extracts. Anesthesiology 1964;25:312–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plataki M, Hubmayr RD. The physical basis of ventilator-induced lung injury. Expert Rev Respir Med 2010;4:373–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1334–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tremblay LN, Slutsky AS. Ventilator-induced injury: from barotrauma to biotrauma. Proc Assoc Am Physicians 1998;110:482–488 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oudin S, Pugin J. Role of MAP kinase activation in interleukin-8 production by human BEAS-2B bronchial epithelial cells submitted to cyclic stretch. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002;27:107–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vlahakis NE, Schroeder MA, Limper AH, Hubmayr RD. Stretch induces cytokine release by alveolar epithelial cells in vitro. Am J Physiol 1999;277:L167–L173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dreyfuss D, Saumon G. Ventilator-induced lung injury: lessons from experimental studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:294–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gajic O, Lee J, Doerr CH, Berrios JC, Myers JL, Hubmayr RD. Ventilator-induced cell wounding and repair in the intact lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:1057–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hotchkiss JR, Simonson DA, Marek DJ, Marini JJ, Dries DJ. Pulmonary microvascular fracture in a patient with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2002;30:2368–2370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moghimi SM, Hunter AC. Poloxamers and poloxamines in nanoparticle engineering and experimental medicine. Trends Biotechnol 2000;18:412–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmolka IR. Physical basis for poloxamer interactions. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1994;720:92–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbs WJ, Hagemann TM. Purified poloxamer 188 for sickle cell vaso-occlusive crisis. Ann Pharmacother 2004;38:320–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodeheaver GT, Kurtz L, Kircher BJ, Edlich RF. Pluronic F-68: a promising new skin wound cleanser. Ann Emerg Med 1980;9:572–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmolka IR. Artificial blood emulsifiers. Fed Proc 1975;34:1449–1453 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh-Joy SD, McLain VC. Safety assessment of poloxamers 101, 105, 108, 122, 123, 124, 181, 182, 183, 184, 185, 188, 212, 215, 217, 231, 234, 235, 237, 238, 282, 284, 288, 331, 333, 334, 335, 338, 401, 402, 403, and 407, poloxamer 105 benzoate, and poloxamer 182 dibenzoate as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol 2008;27:93–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee RC, Hannig J, Matthews KL, Myerov A, Chen CT. Pharmaceutical therapies for sealing of permeabilized cell membranes in electrical injuries. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999;888:266–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee RC, River LP, Pan FS, Ji L, Wollmann RL. Surfactant-induced sealing of electropermeabilized skeletal muscle membranes in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992;89:4524–4528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marks JD, Pan CY, Bushell T, Cromie W, Lee RC. Amphiphilic, tri-block copolymers provide potent membrane-targeted neuroprotection. FASEB J 2001;15:1107–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merchant FA, Holmes WH, Capelli-Schellpfeffer M, Lee RC, Toner M. Poloxamer 188 enhances functional recovery of lethally heat-shocked fibroblasts. J Surg Res 1998;74:131–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng R, Metzger JM, Claflin DR, Faulkner JA. Poloxamer 188 reduces the contraction-induced force decline in lumbrical muscles from mdx mice. Am J Physiol 2008;295:C146–C150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padanilam JT, Bischof JC, Lee RC, Cravalho EG, Tompkins RG, Yarmush ML, Toner M. Effectiveness of poloxamer 188 in arresting calcein leakage from thermally damaged isolated skeletal muscle cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1994;720:111–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma V, Stebe K, Murphy JC, Tung L. Poloxamer 188 decreases susceptibility of artificial lipid membranes to electroporation. Biophys J 1996;71:3229–3241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasuda S, Townsend D, Michele DE, Favre EG, Day SM, Metzger JM. Dystrophic heart failure blocked by membrane sealant poloxamer. Nature 2005;436:1025–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collins JM, Despa F, Lee RC. Structural and functional recovery of electropermeabilized skeletal muscle in-vivo after treatment with surfactant poloxamer 188. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007;1768:1238–1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinhardt RA, Alderton JM. Poloxamer 188 enhances endothelial cell survival in bovine corneas in cold storage. Cornea 2006;25:839–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee YD, Rasmussen DL, Hubmayr RD. Amphiphilic, tri-block copolymers protect rat lungs against ventilator induced injury [abstract]. Presented at the 39th Critical Care Congress, Miami Beach, FL, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plataki M, Lee YD, Rasmussen DL, Hubmayr RD. Poloxamer 188 facilitates the repair of alveolus resident cells in ventilator injured lungs [abstract]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:A1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oeckler RA, Lee WY, Park MG, Kofler O, Rasmussen DL, Lee HB, Belete H, Walters BJ, Stroetz RW, Hubmayr RD. Determinants of plasma membrane wounding by deforming stress. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2010;299:L826–L833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stroetz RW, Vlahakis NE, Walters BJ, Schroeder MA, Hubmayr RD. Validation of a new live cell strain system: characterization of plasma membrane stress failure. J Appl Physiol 2001;90:2361–2370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doerr CH, Gajic O, Berrios JC, Caples S, Abdel M, Lymp JF, Hubmayr RD. Hypercapnic acidosis impairs plasma membrane wound resealing in ventilator-injured lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:1371–1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vlahakis NE, Schroeder MA, Pagano RE, Hubmayr RD. Role of deformation-induced lipid trafficking in the prevention of plasma membrane stress failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:1282–1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson WR, Thielen K. Correlative study of adult respiratory distress syndrome by light, scanning, and transmission electron microscopy. Ultrastruct Pathol 1992;16:615–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costello ML, Mathieu-Costello O, West JB. Stress failure of alveolar epithelial cells studied by scanning electron microscopy. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;145:1446–1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baekmark TR, Pedersen S, Jorgensen K, Mouritsen OG. The effects of ethylene oxide containing lipopolymers and tri-block copolymers on lipid bilayers of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine. Biophys J 1997;73:1479–1491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magalhaes NSS, Benita S, Baszkin A. Penetration of poly(oxyethylene)-poly(oxypropylene) block copolymer surfactant into soya phospholipid monolayers. Colloids Surf 1991;52:185–206 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weingarten C, Magalhaes NSS, Baszkin A, Benita S, Seiller M. Interaction of a non-ionic ABA copolymer surfactant with phospholipid monolayers: possible relevance to emulsion stabilization. Int J Pharm 1991;75:171–179 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grindel JM, Jaworski T, Emanuele RM, Culbreth P. Pharmacokinetics of a novel surface-active agent, purified poloxamer 188, in rat, rabbit, dog and man. Biopharm Drug Dispos 2002;23:87–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jewell RC, Khor SP, Kisor DF, LaCroix KA, Wargin WA. Pharmacokinetics of rheothRx injection in healthy male volunteers. J Pharm Sci 1997;86:808–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tremper KK, Friedman AE, Levine EM, Lapin R, Camarillo D. The preoperative treatment of severely anemic patients with a perfluorochemical oxygen-transport fluid, Fluosol-DA. N Engl J Med 1982;307:277–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tremper KK, Vercellotti GM, Hammerschmidt DE. Hemodynamic profile of adverse clinical reactions to Fluosol-DA 20%. Crit Care Med 1984;12:428–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waxman K, Cheung CK, Mason GR. Hypotensive reaction after infusion of a perfluorochemical emulsion. Crit Care Med 1984;12:609–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vercellotti GM, Hammerschmidt DE. Immunological biocompatibility in blood substitutes. Int Anesthesiol Clin 1985;23:47–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vercellotti GM, Hammerschmidt DE, Craddock PR, Jacob HS. Activation of plasma complement by perfluorocarbon artificial blood: probable mechanism of adverse pulmonary reactions in treated patients and rationale for corticosteroids prophylaxis. Blood 1982;59:1299–1304 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hubmayr RD, Rodarte JR. Acute and long-term effects of Fluosol-DA 20% on respiratory system mechanics and diffusion capacity in dogs. J Crit Care 1988;3:232–239 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ballas SK, Files B, Luchtman-Jones L, Benjamin L, Swerdlow P, Hilliard L, Coates T, Abboud M, Wojtowicz-Praga S, Grindel JM. Safety of purified poloxamer 188 in sickle cell disease: phase I study of a non-ionic surfactant in the management of acute chest syndrome. Hemoglobin 2004;28:85–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Orringer EP, Casella JF, Ataga KI, Koshy M, Adams-Graves P, Luchtman-Jones L, Wun T, Watanabe M, Shafer F, Kutlar A, et al. Purified poloxamer 188 for treatment of acute vaso-occlusive crisis of sickle cell disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;286:2099–2106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheung AT, Chan MS, Ramanujam S, Rangaswami A, Curl K, Franklin P, Wun T. Effects of poloxamer 188 treatment on sickle cell vaso-occlusive crisis: computer-assisted intravital microscopy study. J Investig Med 2004;52:402–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hubmayr RD. Ventilator-induced lung injury without biotrauma? J Appl Physiol 2005;99:384–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dudek SM, Garcia JG. Cytoskeletal regulation of pulmonary vascular permeability. J Appl Physiol 2001;91:1487–1500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Michel CC, Curry FE. Microvascular permeability. Physiol Rev 1999;79:703–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.West JB, Tsukimoto K, Mathieu-Costello O, Prediletto R. Stress failure in pulmonary capillaries. J Appl Physiol 1991;70:1731–1742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.D'Angelo E, Pecchiari M, Della Valle P, Koutsoukou A, Milic-Emili J. Effects of mechanical ventilation at low lung volume on respiratory mechanics and nitric oxide exhalation in normal rabbits. J Appl Physiol 2005;99:433–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krysko DV, D'Herde K, Vandenabeele P. Clearance of apoptotic and necrotic cells and its immunological consequences. Apoptosis 2006;11:1709–1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vlahakis NE, Hubmayr RD. Response of alveolar cells to mechanical stress. Curr Opin Crit Care 2003;9:2–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vlahakis NE, Hubmayr RD. Cellular stress failure in ventilator-injured lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:1328–1342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chanson M, Derouette JP, Roth I, Foglia B, Scerri I, Dudez T, Kwak BR. Gap junctional communication in tissue inflammation and repair. Biochim Biophys Acta 2005;1711:197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laffey JG, Engelberts D, Duggan M, Veldhuizen R, Lewis JF, Kavanagh BP. Carbon dioxide attenuates pulmonary impairment resulting from hyperventilation. Crit Care Med 2003;31:2634–2640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sinclair SE, Kregenow DA, Lamm WJ, Starr IR, Chi EY, Hlastala MP. Hypercapnic acidosis is protective in an in vivo model of ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:403–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wesley UV, Bove PF, Hristova M, McCarthy S, van der Vliet A. Airway epithelial cell migration and wound repair by ATP-mediated activation of dual oxidase 1. J Biol Chem 2007;282:3213–3220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boots AW, Hristova M, Kasahara DI, Haenen GR, Bast A, van der Vliet A. ATP-mediated activation of the NADPH oxidase DUOX1 mediates airway epithelial responses to bacterial stimuli. J Biol Chem 2009;284:17858–17867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.