Abstract

This study explores the lives of Peruvian adolescents in a low-income human settlement outside of Lima. Twenty 12–17 year olds were asked to narrate their own life stories using the life history narrative research method. Holistic content analysis was coupled with a grounded theory approach to explore these data. Intergenerational responsibility, family tensions, economic pressures, racism and violence emerged without prompting and dominated the narrators’ life stories, underscoring the degree to which these adolescents lack access to the supportive individuals and structures that are key to positive adolescent development. The challenges faced by these and the other 5.8 million 10 to 19 year olds in Peru requires increased attention to the role of families, peers and communities in ensuring that adolescents are able to maintain their well-being and achieve their future expectations.

Keywords: Adolescents, Contextual Factors, Qualitative, Life History, Peru

INTRODUCTION

Most researchers agree that adolescence is a transitional period that serves as the bridge between childhood and adulthood. Beyond that basic definition, however, there is great variation. The amount and degree of transitions experienced by present-day adolescents are even greater given significant changes at the individual and societal levels in recent years, particularly in developing countries like Peru. First, the time needed to make the transition to adulthood has expanded due to earlier, healthier entry into puberty, increased amount of time in school, postponed entry into the labor force, and the rising age of first marriage and childbearing, all of which translate into young people spending more time in this “new” developmental stage. Changes in the individual transition are accompanied by changes in the broader environment due to globalization and urbanization. Today’s adolescents are more likely to live in urban areas and smaller households, and to have access to higher levels of education and increased connectivity, through roads, transport, media and the Internet (Lloyd, 2005).

Peru’s estimated 5.8 million 10 to 19 year olds represent the largest percentage of adolescents in the country’s history (INEI, 2005). A number of studies explore adolescence in Peru. A study on street working children and adolescents in northern Lima used ethnographic and interview data collected in the early and mid 1990s to explore boys’, girls’ and parents’ perceptions about work, family and childhood, with the majority of findings focused on work (Invernizzi, 2003). Another study in eastern Lima used semi-structured interviews and surveys to explore resilience with a small population of 13–24 year olds, with the final report centered on the quantitative findings (CORDAID, 2004). Limited studies in Lima have examined specific issues such as adolescent drug use (Gil et al, 2008; Zavaleta, 2006) and alcohol use (Musayón et al, 2008) and a large body of mixed-methods research exists on adolescent sexuality and sexual and reproductive health in Peru’s capital city (Arias & Aramburú, 1999; Cáceres, 1999; Chirinos, Salazar & Brindis, 2000; Magnani et al, 2001; Quintana, 2002; Saravia et al, 1999; Sebastiani & Segil; Yon Leau, 1998).

None of these studies, however, provided the opportunity for young people to explore and express in an open-ended manner how they think about themselves, their development, and the people and contexts that contribute to their lives. The primary goal of this study was therefore to enable adolescents to narrate their lives and describe the contextual factors that have influenced them, using life history interviews -- an adolescent-driven, researcher-facilitated methodology.

METHODS

Study Setting

This study was conducted in Pampas de San Juan de Miraflores, one of the seven zones in the district of San Juan de Miraflores, which is one of Lima’s 43 districts. “Pampas,” established in the early 1980s, is made up of 46 human settlements (pueblos jóvenes) built around a cluster of sand hills located 25 kilometers south of metropolitan Lima. The majority of Pampas’ 57,000 residents live in poverty and, in many cases, extreme poverty. Many Pampas households are overcrowded and a significant number lack basic services such as water, electricity and sewage (Muni SJM, 2003). This site was selected since it is representative of urban adolescents in Peru. Approximately 70 percent of Peruvian adolescents live in urban areas and 27% of the country’s adolescents reside in Lima, with the highest proportions of youth living in peripheral areas and settlements like Pampas (MINSA, 2005).

Study Participants

Twenty 12–17 year olds (5 12–14 year old females, 5 12–14 year old males, 5 15–17 year old females and 5 15–17 year old males) participated in the study. The sampling procedure was non-probabilistic and aimed to ensure that the sample was as diverse as possible within the boundaries of the defined population (Ritchie, Lewis & Elam, 2003). Participants were recruited through community-based organizations, which publicized the opportunity to youth in their respective catchment areas (not only to youth who participated in the organizations). In order to seek out socio-economic diversity, organizations were selected from different zones of Pampas, which represent different socio-economic levels. For example, zones located higher up the sand hills of Pampas tend to be home to people with very low to low socio-economic levels while low-lying zones house people with low to lower middle socio-economic levels. In order to address other diversity-related characteristics, organization leaders asked potential participants to provide their gender, age and school status. Sampling proceeded until there was a large enough sample size for each gender/age sub-group, with participants from different zones of Pampas in each sub-group. An effort was made to include both in-school and out-of-school adolescents.

Participants provided signed assent and their parents/guardians provided signed consent prior to commencing data collection, after reviewing the assent and consent forms and having the opportunity to voice any questions or concerns. This study was approved by ethical review committees at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, MD, USA and the Asociación Benéfica PRISMA in Lima in September 2005 and November 2005, respectively.

Data Collection Activities

Adolescents were asked to be life history narrators (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach & Zilber, 1998). Two facilitators, the first author (a female) and a male research assistant trained in life history research, assisted the young females and males, respectively. Adolescents received a piece of paper and markers and were given all of the time they needed to create a “life history map,” designating and organizing the stages of their lives as they perceived them.

The direction of each interview followed the stages depicted on the adolescent-created map, providing narrators greater control over the direction of their stories. The facilitators’ contributions to the life stories were based on a very open-ended guide that asked about individual identity and significant events, people and activities during each life stage. Facilitators allowed space and time to see if the issues addressed in the guide emerged from the participants themselves, in order to not bias the future direction of the interviews. A total of 40 interviews were carried out, two interviews with each of the 20 participants, during December 2005 and January 2006.

Data Analysis

After the interviews were transcribed, the data were initially analyzed using a holistic content analysis approach in order to understand the full portrayal of each informant’s life, drawing major life themes and patterns, and summarizing how informants characterized their lives, their changing identities and the events and people they considered important (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach & Zilber, 1998). The interviews were then analyzed using a grounded-theory approach to identify categories within the major themes identified in the holistic content analysis until the categories were “saturated” (Glaser, 1998; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). After multiple readings, an initial set of codes created.

Coding was carried out using the ATLAS-ti software program (Scientific Software Development GmbH, 2005). The constant comparison method was used to look back over the transcripts and holistic interview summaries in order to make sure that the smaller “chunks” of data were as representative as possible and to minimize the degree to which ideas were fractured or removed from the overall context of each person’s life history (Coffey & Atkinson, 1996; Lincoln & Guba, 1985). A clear understanding of the meaning of early memories was also essential throughout the data analysis process (Adler, 1929a, 1929b, 1931, 1956; Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach and Zilber, 1998).

RESULTS

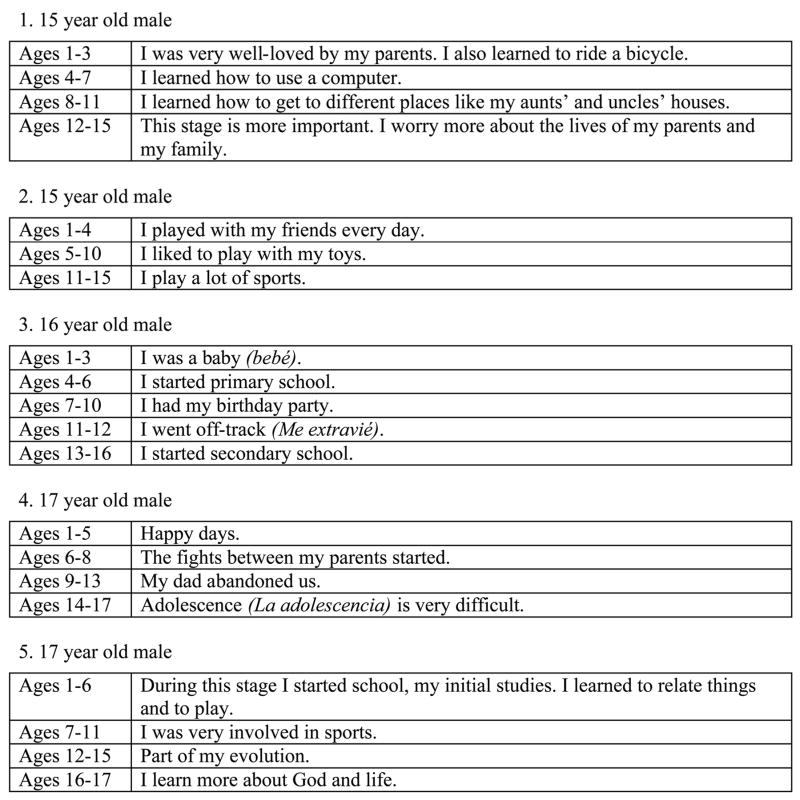

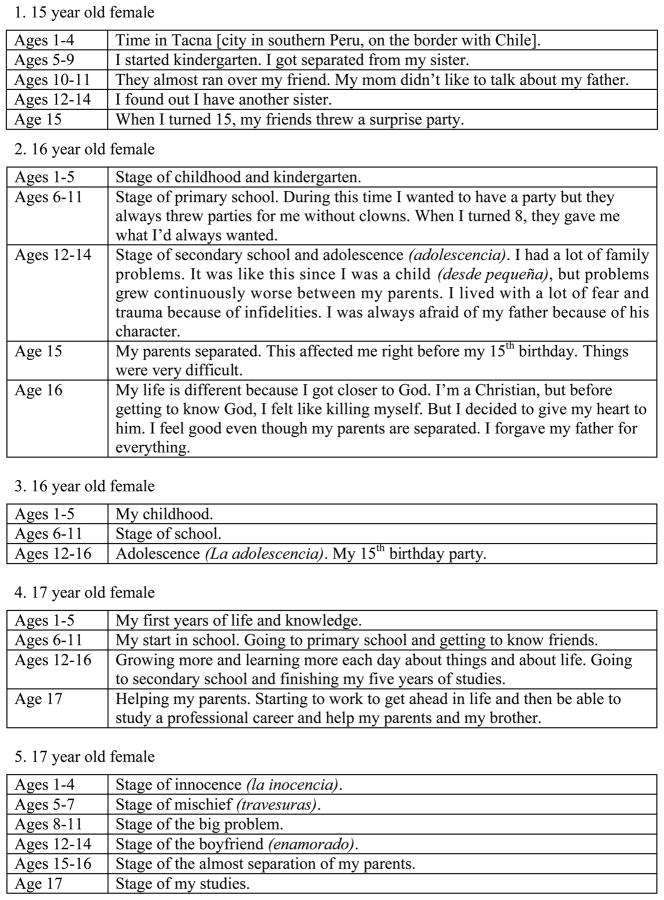

Narrators took between five and fifteen minutes to create their maps, which are included in Figures 1–4. Female participants, and in particular 15–17 year old females, took additional time for thinking and building and put greater detail into their maps. While the content of the maps provides brief insight into participants’ immediate memories about their lives, the narrations give much greater detail about issues of importance for the participants. The results below describe the main themes that emerged in participants’ life histories, both on their maps and during their narrations: happiness and innocence; changes and challenging transitions; family tensions; poverty; racism and violence. The final theme is supports and expectations for the future.

Figure 1.

Life History Maps of 12–14 Year Old Females

Figure 4.

Life History Maps of 15–17 Year Old Males

Happiness and Innocence

The narrators viewed their first years of life as times of happiness, youth and innocence. Many male narrators described these initial years as happy times, while female narrators provided more neutral descriptions, with only one 12–14 year old female stating that the years between ages 4–5 of her life were “very nice.” One narrator’s positive memory of childhood prompted recall of problems that were already beginning and were ever-present throughout her life history. This 16 year old female initially provided a cheerful description of her first day of preschool, but this changed as she continued the explanation:

- The first day [of preschool], [I was] well-dressed, with my uniform, my lunchbox… my mom was the one who took me… she always bought me the things I needed, my lunchbox, hair ribbons, candies… my dad didn’t give me very much, since he… was with another person, with another woman, and I even remember that he didn’t want to give me [money] for my uniform, but since he’s a tailor, he made the uniform…

Changes and Challenging Transitions

The majority of narrators talked about transitions, with both females and males discussing physical changes as markers of these changes. A 12 year old female viewed her first menstruation as a significant turning point from girlhood to womanhood, which also brought changes in her personality:

- When I turned 11, I couldn’t play a lot anymore… I don’t know, because my period came, I didn’t feel like playing all the time… it’s always been like that… I grew very quickly and my personality, I don’t know, I had another mentality… I wasn’t a girl (‘una niña’) anymore.

One 17 year old male narrator also discussed parallels between physical and emotional changes:

- My personality changed, since I started to grow, I started to change a little and my voice also started to change… my voice was delicate, like a little girl’s (‘mujercita’) … when I was young [laughing]… people used to tease me… [saying] ‘little girl,’ things like that… I sounded like a singer, but then later on my voice started to sound manly (‘cachaco’), rough (‘gruesaza’) …

Other narrators also discussed social changes. One 17 year old male narrator talked about the sudden changes he felt from ages 12–15, a stage he entitled “Part of my evolution”:

- Because that’s when I was about to start high school and wow! … a tremendous change… before I was more of a boy (‘un niño’) … and then another type of relationship with the girls (‘chiquillas’) … I spent a lot more time at school… when you get to high school everything seems bigger… you get paralyzed, sometimes [there are] parties, parties… all of that.

One 17 year old female narrator described her perceptions of the effect that adolescence had on the daily behaviors of her female classmates and friends:

- Girls (‘niñas’), when they become adolescents (‘adolescentes’), they change their character, they act more restless (‘inquietas’), they tease the boys… they draw things on their skirts, they’re out of control (‘se pasaban mucho’) … they’re very crazy (‘muy locas’), and ummm… they don’t go to class… and they don’t do their homework either… they relax a lot… they change from being calm and decent (‘tranquilas’) …

These physical and social transitions, however, were overshadowed by undue responsibilities and burdens. One 15 year old male talked about the greater importance of adolescence, as compared to childhood:

- This stage is more important. I worry more about the lives of my parents and my family.

These responsibilities and burdens were due to family tensions, social pressures, poverty, racism and violence. The following sub-sections present in greater detail the challenges faced by adolescents in this context.

Family Tensions

Family tensions had a significant presence in the narrators’ life maps. For all narrators, family issues translated into sizeable emotional stresses. One 12 year old male cited “abandonment by my mother” at age 12 on his life map. One 17 year old male dedicated eight years to family problems, including fighting between his parents from ages 6–8 and abandonment by his father from ages 9–13. Three females also devoted multiple life stages to family struggles. One 17 year old female described six years of challenges in her family, from ages 8–16, including the “almost separation” of her parents. One 16 year old female provided significant detail about her family issues, stating the following about ages 12–14:

- I had a lot of family problems. It was like this since I was a child, but problems grew continuously worse between my parents. I lived with a lot of fear and trauma because of infidelities. I was always afraid of my father because of his character.

These problems were ever-present in this narrator’s life, but she did not bring them to the forefront of her life experience until the stage she entitled “secondary school and adolescence.”

One 15 year old female did not talk as overtly about family problems, but the presence of continuous traumatic events on her map draws attention to significant family dissolution. From ages 5 to 14, she described being separated from her sister and then finding out she has another sister, and also wrote that her mother didn’t like to talk about her father.

The 17 year old female narrator who talked about how female adolescents change their characters and behaviors during adolescence explained that she did not do so due to problems in her household:

- I wasn’t as mischievous (‘traviesa’), I was more reserved (‘reservada’) … I wasn’t very restless (‘muy inquieta’) … it wasn’t in my nature since there were problems in my house… since there were problems, my character changed for the worse… I was a little more introverted, as they say.

The same narrator described significant family responsibilities as part of her daily activities, a contrast to her peers’ activities:

- [Every day] I help my mom cook, go to the market to buy things… help my dad make empanadas, clean the cans, paint the empanadas, cut up the onion… My friends are all studying, others are working… my closest friend studies… my other friend does too.

Another female narrator also discussed undue stresses occasioned by her parents. This 13 year old worked every weekday selling fruit at her mother’s business and on Saturdays helping her aunt with her business, no longer leaving her time to go to the Internet or play as she used to do. One 15 year old male narrator depicted economic strains due to lack of work opportunities for his parents, which motivated him to invest more effort in his studies:

- [In my house, my parents] talk… they worry… my dad says to my mom, ‘I don’t have a job, what am I going to do?’ … ‘Don’t worry, you’ll get a job’ [my parents respond] … We [my siblings and I] don’t say anything. But I think, I’m going to put more effort into my studies because he [my father] loves us…

Additional narrators related other family experiences that symbolize considerable emotional stresses, particularly for young people. One 17 year old female participant described frequent comments by her mother:

- ‘I keep putting up with your dad because of you, but the day that you [start to] study at the university, we’re going to separate’… ‘you’ll help me with your brother’… and since right now I’m preparing [for the university] … my mom always tells me, even now, ‘get in quickly, get in quickly’… There’s no solution for them, they’re going to separate, because my mom sometimes, it’s like she’s telling me, ‘ok, I’m tired of being here’…

In addition to making her daughter feel responsible for her parents remaining in an unhappy marriage, the narrator’s mother also mentioned future pressures given her expectation that the narrator will help take care of her younger brother. One 17 year old male narrator experienced similar strains, since his mother drew him into her problems with his father and since his parents fought openly in the house:

- Almost every conversation [with my mom] was about my dad and nothing else, ‘your dad hasn’t come home, where could he be’… and we’d even go to look for him… sometimes he wouldn’t be there and he’d come back 3 or 4 days later… [My parents] would fight… [about how] he didn’t bring her the check… my dad would hit her… he’d be hitting her, you could hear everything.

A 15 year old female narrator also described how her mother and stepfather fought constantly and violently about economic struggles, with her and her sisters present:

- I am always there… [my mother and stepfather] argue, yell, fight… he’ll kick her and even pull her hair… I watch and cry, that’s all… I’m afraid that if I get in the middle, he’ll hit me… they’re always arguing about money… they sometimes borrow money from a neighbor, a woman who lends money… my mom tells him to pay, he says he doesn’t have it… my dad reacts and hits her, then he calls her an [expletive] … in front of my sisters and [name of sister] gets nervous and starts to cry.

While considerable family crises and responsibilities were present in many of the narrators’ life histories, a few of the 15–17 year old male narrators also discussed significant social pressures to join gangs:

- I felt good sometimes being with them, talking… and since they already knew me… [members followed the leader] because they thought that he was a leader for the future… it could be that in a way everyone feels some kind of attraction to that type of person… and when I’d go to a certain place, right, and they wanted to fight with me, they already knew that I hung out with him, right… and nothing happened.

The Role of Poverty

Economic stresses triggered many family arguments and placed undue burden on the adolescent narrators. Economic stresses also cross-cut many aspects of everyday life and exerted a strong influence on adolescents’ future goals and opportunities. One 16 year old female narrator mentioned lack of money multiple times, including the following:

- We went on a trip… I remember that a friend didn’t bring her lunch… [and] she came without eating breakfast… they’d only given her money to pay her bus fare… she didn’t have anything else… so we all gave her something, we took something from each plate…

One 13 year old female narrator who lived in a city in the Andes region of Peru until age eight recounted how her brother tried to commit suicide because he didn’t have one nuevo sol (about 30 U.S. cents) for the Internet, confirming the powerful role of economic resources:

- My brother… wanted to hang himself… he asked my mom for money, ‘give me one sol,’ and she didn’t want to… ‘it’s late, tomorrow I’ll give it to you’… and he said, ‘I won’t ask for anything else from you’… my mom went to sleep and then she heard noise… she went running and found my brother hanging… they went to the hospital… he’s okay now.

Economic resources also played a critical role in the fulfillment of the narrators’ goals. One 17 year old male narrator discussed how he couldn’t continue advanced schooling due to lack of resources:

- Right now, my parents don’t have [money]… I mean, they have economic problems… and the studies I’m going to do [in sound engineering] are very expensive… it’s possible that I’ll study in March [in three months]… possibly not… I might not be able to do it for economic reasons… then maybe in August, since during that time, I could get… a job.

One 17 year old female narrator’s story echoed that of the potential sound engineer. She had to alter her aspirations to adapt to her family’s economic possibilities:

- I want to study computer science… before I wanted to study veterinary medicine, but that’s expensive… I don’t have that [kind of money], [since] you have to study at the university… with my mom, we’re finding out how much it costs for a good place to prepare myself… you have to pay 500 [soles – about 170 U.S. dollars] I think, 200 first… but I still can’t since my mom doesn’t have the money they want for registration…

Another 17 year old female narrator who continued studying beyond high school substantiated the previous narrators’ concerns about the significant costs of further education. Her parents made important sacrifices in order for her to continue her studies, as seen in her response to a question about what her house is like:

- It has a poor floor (‘un piso pobre’) [laughing]… they [my parents] can’t build more because I study… my parents have enough for food and for my studies, that’s it… they pay 1,500 [soles – about 500 U.S. dollars] for six months… it’s very expensive and since the first payments are divided up, and sometimes they can’t pay, they borrow money or my mom holds an event to collect money.

The Presence of Racism and Violence

Racism and violence also played a substantial role in the narrators’ lives, racism in the case of two and violence in the case of the great majority. One 12 year old female narrator mentioned racism as part of the title for the stage of ages 6–10: “people here are racist, but there are also good people.” In her narrative, she explained further:

- People here [in this neighborhood] are very racist because they’re always saying negra (black), serrana (person from the Andes region), chola (mixed Amerindian/Spanish)… people here are very ignorant about these things… I don’t like it… but now I don’t pay attention to them.

One 14 year old male narrator described significant racism toward him and his father, with neighbors and other people calling them negro (black), even though they self-identify as zambo (mixed Amerindian/African):

- They insult you for the heck of it, they talk to me in Quechua [indigenous language] and I understand a little bit… and I tell them, speak to me correctly… they insult my dad in Quechua too… I hear them call my dad negro this, negro that, and their insults bother me… I don’t like them to call me negro… they could say to me, ‘you’re going to die, zambo,’ but negro makes me mad.

Racism has affected this narrator to such a degree that he wants to move away from his community because of it. When asked about his dreams for the future, he responded:

- Go live somewhere else… sometimes people insult me… they say, ‘that bad-mannered (‘malcriado’) negro’… and that’s why I want to leave… I don’t want to have problems.

Racial harassment is in itself a type of violence. Narrators also described other types of verbal and physical violence: violence at home, both between parents and between parents and children; violence between peers; and general violence in the community. Many narrators recalled parental violence toward them, often during childhood. One 12 year old female narrator recounted how earlier physical violence later become verbal violence:

- When I was a girl (‘niña’), my dad used to hit me… with a belt… and I told my mom and she called him out on it… and she filed a complaint against him… then we came here [to this neighborhood] with my dad… he no longer hits me but he always yells at me, insults me and my mom always fights with him because of it…

One 12 year old male narrator talked about his mother’s physical violence toward him and his siblings when she would get upset about them engaging in everyday childhood activities:

- My mom would hit us when she was upset… [like] when my younger siblings would make her angry when they went outside and came back dirty… then she’d get upset.

The narrators also discussed violence with their peers. One 13 year old female narrator talked about violence with her classmates:

- They insult me… and I don’t like them to insult me… it makes me feel, I don’t know… it makes me want to hit them… at school, I’ve grabbed them… I mean, I’ve fought with them… we’ve pulled each other’s hair… I don’t know, for no reason I just hit them…

Several male narrators described peer violence in the context of gang fighting. One 17 year old narrator recalled his involvement:

- We would go down [the hill] because that’s where the fights were… there on the soccer field between everyone from up top and the people from here… my friends would call me, ‘let’s go, don’t you want to’… ‘are you scared, let’s go’… I would go in the back, but then they’d put me up front… here they fight… in their pants they hide a knife… then they take it out… and my friends told me, ‘you fell backwards and right behind you were two guys (‘patas’)’… ‘one with a big rock and one with a knife they were going to stick into you’… [but] my friends saw when I fell and they picked me up and took me to the back… the others kept fighting… we were 15 [people] and they were about 50…

Supports and Expectations for the Future

Although pressures and tensions dominated participants’ narrations of their adolescent years, the majority closed their stories with something positive. One group of memories, especially among females, centered on how much participants valued their friends and family, despite numerous family tensions. A second group focused on their future expectations, despite numerous barriers to meeting these expectations.

When asked about the most important people in their lives, respondents answered their family as well as their friends. A 12 year old female mentioned the importance of her uncle, who supported her while her parents were having problems:

- My uncle [name of uncle] [is important]… because when my mom lived separated from my father, I lived with him [my uncle]… I love him a lot… I talk with him. He takes me out… he comes to my birthday, on Christmas, on my grandmother’s and mother’s birthdays.

A 16 year old male talked about how he likes to watch television with one of his brothers:

- We watch television. We watch shows… we laugh and tell jokes to the other person… with my brother, because my older brother is with his partner.

A 17 year old female described visiting and going out with friends:

- My closest friend lives in [name of nearby district of Lima]… I go to her house to talk… sometimes I see her at the market. Then we go out for a little while or to a party… they invited me to go to the anniversary of their institute. I wanted to go, but my mom didn’t want me to go because she [my friend] is studying and my mom said that I might feel bad. But I told her that I wanted to go, that I’m also going to study.

Three out of five of the 15–17 year old females also mentioned their quinceañera celebration for their fifteenth birthdays, a party with family and friends with dancing, eating and general celebrating. As one 15 year old described:

- They threw a party when I turned 15. It was a very beautiful day, here in my house, with my friends, my family, my cousins, my aunts and uncles, my dad, my mom… I danced the waltz… my dad spoke, my mom [too], we took photos, there was a ring in the cake, and my friends had to pull it out… it was very nice.

Participants also described their future expectations, with differences between female and male participants:

- I want to finish high school and be a biologist… I just want to study… I’d like to study at a university. (12 year old female)

- [I plan] to keep studying… My father told me that I should study pharmacy while I work… but I want to study psychology… My father said, ‘If you apply to the university and don’t get in, you’ll need to work and then apply.’ ‘No, I will get in,’ I told my father, ‘and into psychology. Don’t you see, I want to study psychology’… child psychology. I would like it since there are a lot of children that aren’t understood by their parents… I want to counsel them, help them, since it will be good for them. (16 year old female)

- I will finish [secondary school]… [then] study for nursing… I plan to study at [name of institute]. (15 year old female)

- I want to be a police officer… because I would like my community to be calm… sometimes my friends fight and I separate them, in my class too…[I want to] help, protect people. (12 year old male)

- I only want to have a stable job… something to maintain my family… any type of job. I don’t want to be marginalized (‘marginado’) or stepped on (‘pisoteado’). (17 year old male)

- [I want to] work in [name of a government-sponsored training program for youth]… it lasts 6 months… 3 months of theory and 3 months of practice. During the practice [component], they give you businesses where you can practice… if you do a good job, you could stay there to work… I want to be a chef or a bartender. (16 year old male)

- I want to study something technical because I don’t plan to go to the university… it’s not easy to get in… my mother wants me to go to the university… [she says] that if I want to be an electrician, I could be an electrical engineer… not just an electrician… I could be an electrical engineer. (14 year old male)

All of the female participants planned to study beyond secondary school, with a few mentioning technical institutes and most aiming for university-level studies. The future expectations of male participants were lower: two mentioned university-level studies and the others, who represent the majority, planned to work in service or technical jobs that require short-term training. Females were also more certain of future success and had more concrete plans.

DISCUSSION

These life histories reveal important insights into the lives of adolescents from human settlements in Lima, Peru, a setting that is representative of urban adolescents from families of very low to lower middle socioeconomic levels. The adolescents’ detailed narratives confirm that adolescents’ lives are incredibly complex and that all of the factors highlighted in their life histories interact in order to influence each individual adolescent. One significant limitation of this study was the difficulty of presenting an accurate representation of the rich information that adolescents so generously shared about their lives. The adolescent narrators produced many hours and subsequently pages of life stories, which the authors worked to synthesize and summarize in a manner that represents these adolescents’ voices and lives.

Adolescents’ life maps and life histories both opened with positive recollections of their childhood years. Applying the approach of Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach and Zilber (1998), based on Alfred Adler’s belief system, a revisiting of the narrators’ generally positive early childhood memories suggests that the great majority of participants have a positive perspective on their current life situation and future life possibilities, even in the midst of significant current challenges. These positive early memories could be influenced by recall bias, when participants are unable to accurately recall memories, and in particular early memories. As discussed in a recent article on life histories with adolescents, adolescent memories of their early childhoods are often vague, lacking in detail and less clear than memories from their more recent past (Haglund, 2004).

It is important, however, to refer to Adler’s vision of early memories as personal creations based on one’s current situation and goals, a vision that was applied in the current study. Given the repeated presence of challenges, it is unclear whether this positive perspective on life is real, in the sense that participants truly perceive positive dimensions of their current lives and believe that positive outcomes are possible in the future, or imagined, in the sense that participants want to create positive aspects of the present and future by holding on to, or even inventing, a positive past. One 16 year old female participant’s early memories, quoted in the happiness and innocence section of the Results, provide evidence of this real versus imagined dichotomy. Although she attempted to present a positive retelling of her first day of preschool by detailing how her mother worked to meet all of her needs, budding family dissolution almost immediately dominated her description when she mentioned that her father did not play a significant role in her initial schooling experience or her childhood, an issue that was ever-present in her life story. The majority of the participants, however – including this 16 year old female – closed their narratives with a positive vision of their future, as shown in the final subsection of the Results. These positive expectations confirm Adler’s theory, although it would be important to explore these expectations in greater depth in order to draw conclusions.

It is also interesting to highlight that many of the narrators’ early memories were triggered and/or strengthened by photos of the events that adolescents had in their homes. This affirms that where research takes place matters and that, when it’s in a setting that is selected by and familiar to the participants, additional information may emerge. The research team implemented various additional measures to make the interview as comfortable as possible for participants and to minimize social desirability bias, which could lead to adolescents providing responses that they thought might please the interviewer or that reflected acceptable social norms (Gregson et al, 2002). This includes one-on-one interviews with a facilitator of the same sex; a two interview structure in order to establish improved rapport; and participant determination of the direction and most of the content of the interview through the creation of the life history map.

The topics that emerged spontaneously and consistently to dominate participants’ narrations, including personal responsibilities and burdens due to family tensions, social pressures, economic struggles, racism and violence, affirms the success of these measures that were taken by the research team. Narrators recognized adolescence as either a neutral or difficult stage, through memories that contrast their adolescent experience with that of their peers. Stories of contrast usually demonstrated how the participants perceived that their peers were able to fully experience their adolescence, while the narrators themselves were unable to do so because of personal responsibilities and family problems. One 17 year old female narrator’s story reflects the narrations presented by the other participants. She animatedly related how her peers “went crazy” and significantly changed their behaviors upon reaching adolescence, but then reflected on how she could not do the same due to problems at home and since she had to help her mother with household responsibilities and her father with his work responsibilities.

Participants’ socio-economic level plays an important role in their lives. A recent study on street working children and adolescents in Lima confirmed differences in participants’ life experiences based on parental origin and socioeconomic status (Invernizzi, 2003). While in-migrants from rural areas of the Peruvian Sierra (Andean region) tend to adapt and often replicate their references of children contributing to family work responsibilities in their new urban setting (Golte & Adams, 1987), urban, typically middle class residents view childhood as dedicated to education and play (Invernizzi, 2003). The adolescent narrators’ stories reflect these findings, although economics appears to act as a mediating factor in the relationship between parental origin and beliefs about childhood responsibility. The most significant work burdens were placed on the 13 year old female narrator who was born and raised in the Sierra and whose family suffered constant economic struggles and on the 17 year old female who wasn’t able to “go crazy” like her adolescent peers since she had significant household and work responsibilities in her household with constant economic stresses and parents from the Sierra. Although other participants described sizeable emotional pressures during adolescence, they did not narrate stories of such great household or work responsibilities. The majority of the other narrators have parents who are from the Peruvian Sierra, but they also have higher socioeconomic levels than the two female narrators just described,1 a factor that may contribute to the contrast between the participants’ experiences.

There is also evidence of clear gender differences. Female narrators tended to provide more detailed, complex narratives than their male counterparts. While females’ narrations incorporated lengthy retellings of important people and events, males tended to recall everyday or more general activities. Additionally, both male and female participants discussed personal challenges and emotional stresses. Their responses, however, were quite different: while females internalized these personal challenges by associating them with emotional difficulties and additional personal responsibilities (which seem to be both perceived and real), males tended to limit their narrations to recounting the stresses and, in a limited number of cases, externalizing them through social pressures such as gangs. These contrasts suggest gender differences in socialization, with female development more focused on family and interpersonal relationships and males raised to look outward and be more independent. This confirms past research on gender differences in autobiographic memory with middle-class children in the United States (Buckner & Fivush, 2000). Other research has examined cultural differences in autobiographic memory and self-description between European American and Chinese children (Wang, 2004) and college students (Wang, 2001). However, additional research on gender differences in an international context was not identified.

Finally, structural violence is ever-present in the participants’ life history narratives. Structural violence asserts that economic, cultural, political, legal and religious structures disallow individuals, groups and societies from reaching their potential (Galtung, 1969). Scheper-Hughes (2004) expresses her perspective on structural violence in the following: “Structural violence is violence that is permissible, even encouraged… [It] refers to the invisible social machinery of inequality and oppression that reproduces pathogenic social relations of exclusion and marginalization via ideologies and stigmas attendant on race, class, caste sex, and other invidious distinctions” (p. 14). In her work with “marginalized” urban youth in Brazil and South Africa, the author found that this social machinery, a term originally developed by Farmer (2004), drives individuals – and even people from their own socioeconomic class and community – to reduce socially vulnerable individuals into “expendable” non-persons (Scheper-Hughes, 2004). This practice of reducing socially vulnerable people was confirmed by adolescent participants in this study, who narrated how they are socially vulnerable given the physical, psychological and cognitive transitions that they experience and how they are brought down by the stresses, economic problems, violence and racism that they face in their often-fragile families, households and communities. The absence of structures to counter structural violence translates into undue burdens and constrained opportunities for adolescents and brings about diverse types of actual violence, as seen in the racism experienced by a few of the narrators and the family, peer and community violence recounted by all narrators. These manifestations of violence are, as Scheper-Hughes found, perpetrated by people from the narrators’ socioeconomic class and community, and often by their families – evidence that the violence of macro-level structures has penetrated this community to such a degree that individuals and groups who should provide mutual support and advocate for alternatives to overcome structural violence now help to reinforce its detrimental effects on the most vulnerable.

CONCLUSIONS

The adolescent narrators constructed complex stories that demonstrate the diverse, multifaceted factors that have influenced their lives throughout adolescence and childhood. Typically happy or neutral descriptions of childhood were overshadowed by family problems, personal responsibilities, social pressures, economic struggles, racism and violence, all of which introduced constant emotional stresses and challenges into the narrators’ lives. Future research could further explore adolescents’ future outlook and aspirations and their perceptions about the likelihood of fulfilling their future goals, as well as how gender roles and the diverse contextual factors described by adolescents in their narratives play a role in the fulfillment of these objectives. Results from this study can be used to inform adolescent development policies and programs, particularly in providing information about the role of families, peers, communities and other contextual factors in ensuring adolescents’ current and future well-being. Alternative structures to counter the numerous challenges described by all narrators, including adequate, high-quality general and mental health services, high-quality educational institutions, work opportunities, and individual and community-based development programs and services, are needed.

Figure 2.

Life History Maps of 15–17 Year Old Females

Figure 3.

Life History Maps of 12–14 Year Old Males

Acknowledgments

Angela Bayer is currently a Postdoctoral Scholar under NIH NIMH grant T32MH080634-03. We are very grateful for the support and assistance of research assistant Danilo Climaco and PRISMA field workers, and to the adolescents who shared their life stories for this study.

Footnotes

Socioeconomic level in this study was judged by a variety of factors: the specific location of the household within the study community (some areas are more developed than others); the prevalence of descriptions of economic struggles during the narrators’ life histories; the household flooring material in each narrators’ household; and the research team’s observations of the narrators’ homes (number of rooms, possession of items like a refrigerator and a television).

References

- Adler A. The Individual Psychology of Alfred Adler. New York: Harper Torchbooks; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Adler A. The Practice and Theory of Individual Psychology. New York: Harcourt and Brace; 1929a. [Google Scholar]

- Adler A. The Science of Living. New York: Garden City; 1929b. [Google Scholar]

- Adler A. What Life Should Mean to You. Boston, MA: Little, Brown; 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Arias R, Aramburú CE. Uno Empieza a Alucinar … Percepciones de los jóvenes sobre sexualidad, embarazo y acceso a los servicios de salud: Lima, Cusco e Iquitos. Lima, Perú: Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, REDESS Jóvenes; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JP, Fivush R. Gendered themes in family reminiscing. Memory. 2000;8:401–412. doi: 10.1080/09658210050156859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres CF. La (Re)Configuración del Universo Sexual. Lima, Perú: Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, REDESS Jóvenes; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chirinos JL, Salazar VC, Brindis CD. A profile of sexually active male adolescent high school students in Lima, Peru. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2000;16:733–746. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2000000300022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey A, Atkinson P. Making Sense of Qualitative Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Catholic Organisation for Relief and Development Aid (CORDAID) Resiliencia de jóvenes urbanos en Lima. Lima, Perú: CORDAID; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer P. An anthropology of structural violence. Current Anthropology. 2004;45:305–326. [Google Scholar]

- Galtung J. Violence, peace, and peace research. Journal of Peace Research. 1969;6:167–191. [Google Scholar]

- Gil HL, Mello DF, Ferriani MG, Silva MA. Perceptions of adolescent students on the consumption of drugs: A case study in Lima, Peru. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. 2008;16:551–557. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692008000700008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG. Doing Grounded Theory: Issues and discussions. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine de Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Zhuwau T, Ndlovu J, Nyamukapa CA. Methods to reduce social desirability bias in sex surveys in low-development settings: Experience in Zimbabwe. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29:568–575. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200210000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haglund K. Conducting life history research with adolescents. Qualitative Health Research. 2004;14:1309–1319. doi: 10.1177/1049732304268628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI) Perú en Cifras. Lima, Perú: INEI; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Invernizzi A. Street-working children and adolescents in Lima: Work as an agent of socialization. Childhood. 2003;10:319–341. [Google Scholar]

- Lieblich A, Tuval-Mashiach R, Zilber T. Applied Social Research Methods Series. Vol. 47. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. Narrative Research: Reading, analysis, and interpretation. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba GE. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd C, editor. Growing Up Global: The changing transitions to adulthood in developing countries. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Magnani RJ, Seiber EE, Gutierrez EZ, Vereau D. Correlates of sexual activity and condom use among secondary-school students in urban Peru. Studies in Family Planning. 2001;32:53–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Salud (MINSA). Perfil de la Población. Lima, Perú: MINSA – Oficina General de Estadística e Informática; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Municipalidad de San Juan de Miraflores (Muni SJM). Plan de Desarrollo Integral de San Juan de Miraflores 2003–2012. Lima, Perú: Muni SJM, Equipo Técnico PDI; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Musayón Y, Alayo M, Loncharich N, Armstrong M. Factors associated with alcohol consumption in schoolgirls in a school in Lima, Peru. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 2008;19:188–194. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana AS. Itinerarios de salud sexual y reproductiva de los y las adolescentes y jóvenes de dos distritos de Lima. In: Cáceres C, editor. La Salud Sexual Como Derecho en el Perú de Hoy: Ocho estudios sobre salud, género y derechos sexuales entre los jóvenes y otros grupos vulnerables. Lima, Perú: REDESS Jóvenes; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J, Lewis J, Elam G. Designing and selecting samples. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, editors. Qualitative Research Practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Saravia C, Apolinario H, Morales R, Reynoso B, Salinas V. Itinerario del acceso al condón en adolescentes de Lima, Cusco e Iquitos. In: Cáceres C, editor. Nuevos Retos: Investigaciones recientes sobre salud sexual y reproductiva de los jóvenes en el Perú. Lima, Perú: REDESS Jóvenes; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Scheper-Hughes N. Dangerous and endangered youth: Social structures and determinants of violence. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1036:13–46. doi: 10.1196/annals.1330.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani A, Segil E. Qué hacen, qué piensan, qué sienten los y las adolescentes respecto a la salud sexual y reproductiva. In: Cáceres C, editor. Nuevos Retos: Investigaciones recientes sobre salud sexual y reproductiva de los jóvenes en el Perú. Lima, Perú: REDESS Jóvenes; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. Culture effects on adults’ earliest childhood recollection and self-description: implications for the relation between memory and the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:220–233. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. The emergence of cultural self-constructs: autobiographical memory and self-description in European American and Chinese children. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:3–15. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yon Leau C. Género y Sexualidad. Una mirada de los y las adolescentes en cinco barrios de la ciudad de Lima. Lima, Perú: Movimiento Manuela Ramos; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zavaleta A, Castro de la Mata R, Maldonado V, Romero E. Características y Opiniones sobre Drogas en Escolares de Cuarto y Quinto de Secundaria. Lima, Perú: Centro de Información y Educación para la Prevención del Abuso de Drogas (CEDRO); 2006. [Google Scholar]