Abstract

Objective

We examined trends in treatment and survival in a population-based sample of white patients diagnosed with local and regional stage cutaneous melanoma in 1995, 1996, or 2001, treated in communities across the United States with vital status follow-up through 2007.

Methods

White patients age 20 or older with invasive cutaneous melanoma were identified from the SEER population-based registries. Hospital and pathology records were re-abstracted and physicians asked to verify therapy provided.

Result

The percentage of patients receiving lymph node biopsies increased over time. Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) increased between 1995 and 2001 from 5% to 32% for men and 9% to 35% for women. The use of chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and immunotherapy changed little. Facilities with approved residency training programs were more likely to perform lymph node dissections, to perform SLNB, and to treat patients more aggressively than were facilities without such programs. Men were significantly more likely than women to die of cutaneous melanoma. In multivariable survival analysis, after adjusting for age, Charlson Score, and surgical margins, survival did not change significantly over this time.Deaths were associated with increasing tumor thickness for men and women.

Conclusion

Surgical treatment of local or regional melanoma became more extensive over time with fewer local excisions and more lymph node dissections, but with little change in adjuvant therapy. Survival was associated with tumor thickness. Early detection when the tumor thickness is less may decrease mortality. Future research should especially target decreasing the disparity in survival between men and women.

Introduction

Cutaneous melanoma incidence has been increasing over the past 30 years from 7.9/100,000 in 1975 to 23.1/100,000 in 2008.1 Incidence rates increase with age and are higher in females until the age of 50 when the rates become higher in males. Cutaneous melanoma is much more common in non-Hispanic whites than in Blacks. During the time period 2001-2007, approximately 84% of these cancers were localized at diagnosis, 8% were regional, 4% were distant, and 4% were unstaged. The 5-year relative survival rates have increased over time, from 83% for patients diagnosed between 1975 and 1979 to 93% for patients diagnosed in 2001-2007. The rates for the time period 2001-2007 show a 98% 5-year relative survival for patients diagnosed with localized disease and a 61% 5-year survival for patients with regional disease. In 2011, an estimated 70,230 cases of cutaneous melanoma will be diagnosed and 8,790 people will die of melanoma.2

The primary treatment for melanoma is surgery with wide excision of the tumor. The recommended margins depend on the thickness of the tumor.3 Treatment recommendations for more extensive disease include interferon-α, radiation, vaccines or isolated limb profusion with melphalan. High-dose interferon has been shown to improve disease-free survival, and two of the three studies of high-dose interferon showed an overall survival advantage.4,5,6 However, melanoma with distant spread at diagnosis is rarely curable.7

The National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) patterns of care study data allow for the examination of trends over time in the distribution of cutaneous melanoma by anatomic site, therapy provided, the characteristics of the medical facility where the primary treatment was given, and the survival of patients with localized and regional disease. These population-based samples of cases were diagnosed in 1995, 1996, or 2001.

Methods

NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End-Results (SEER) program includes a set of population-based registries that collect data on all cancer cases occurring in defined geographic areas. From 1992 through 1999, SEER data covered 14% of the US population; coverage increased to 26% in 2000.8 SEER collects detailed information on tumor characteristics, demographics, and treatment and maintains follow-up of all registered cases. The data are primarily abstracted from hospital records, surgical centers and radiation facilities. Because adjuvant therapy is most often provided in an outpatient setting, NCI annually selects certain cancer sites and supplements the routine data abstraction with patterns of care studies. In addition to re-abstracting the data, each patient’s physician was asked to verify the treatment provided. These physicians also were asked whether other physicians might have provided care and if so, the newly identified physicians were then contacted. To assure consistency of abstracting and coding, the supervising abstractor from each registry attended a central training.

The current data include white patients who were age 20 or older and diagnosed with local or regional melanoma in 1995, 1996, or 2001. Patients were ineligible if they had previously been diagnosed with cancer other than non-melanoma skin, were diagnosed on the death certificate or at autopsy, or were diagnosed simultaneously with a second cancer. African-American patients were not sampled because of their low incidence rate of melanoma. The nodal biopsy technique performed on each patient was independently abstracted from their medical record and did not rely on information provided by cancer registry data. Patients were identified as having a sentinel lymph node biopsy if the medical record provided any indication of the procedure and was recorded regardless of any subsequent lymph node dissection (e.g. complete nodal dissection) performed. In 1995, 1996, and 2001 a total of 262, 751, and 1200 patients, respectively, were identified from participating registries. The registries participating in the patterns of care studies changed over time. Because this study focused on trends over time, we limited the registries to those participating in at least two of the three years (the metropolitan areas of San Francisco, San Jose/Monterey, Atlanta, Detroit, Seattle, Los Angeles County, and the states of Connecticut, Iowa, New Mexico, and Utah). This excluded an additional 479 cases.

Bivariate analyses were performed to determine the association between certain tumor characteristics and clinical, non-clinical, treatment variables, as well as the year of diagnosis. All estimates were weighted to reflect the population from which the sample was drawn. The sample weights, calculated as the inverse of the sampling proportion for each sampling stratum (defined by SEER registry, white Hispanic / white non-Hispanic ethnicity and sex), were used to obtain estimates that are representative of all eligible Caucasians melanoma patients in the study areas. We used the statistical software SAS and SUDAAN (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC). The SUDAAN software allows for use of sample weights and adjusts the standard errors appropriately.

Follow-up was available through December 31, 2007. In a multivariate Cox proportional hazard model we examined melanoma-specific mortality by sex adjusting for age group, Charlson Score, tumor thickness, margins, and year of diagnosis. All tests were two-sided.

Results

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

In 2001 less than 32% of men, but more than 48% of women were diagnosed with localized or regional melanoma at age 49 or younger (p<0.0001) (Table 1). Between 1995 and 2001 the percentage of patients who had no insurance decreased (p = 0.056). The percentage of patients treated in a facility with an approved residency training program, dropped from about 60% to 50%. The percentage of patients classified as “malignant melanoma, not otherwise specified” increased and the percentage reported to have the superficial spreading histology decreased.

Table 1.

Weighted Percent Distribution of Non-clinical, Tumor Characteristics and Vital Status of Patients Diagnosed with Non-Metastatic Melanoma by Year of Diagnosis with Follow-up through 2007

| 1995 | 1996 | 2001 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Number of Case | 140 | 123 | 391 | 361 | 353 | 367 |

| Age at Diagnosis | ||||||

| 20-29 | 4.3 | 7.4 | 4.9 | 12.1 | 2.4 | 7.6 |

| 30-39 | 13.1 | 19.8 | 13.1 | 22.2 | 7.9 | 15.5 |

| 40-49 | 18.9 | 28.0 | 19.3 | 23.4 | 21.4 | 25.3 |

| 50-59 | 15.4 | 12.4 | 14.7 | 11.9 | 21.9 | 16.5 |

| 60-69 | 28.3 | 19.1 | 24.9 | 10.8 | 18.5 | 14.5 |

| 70-79 | 13.4 | 5.2 | 15.4 | 11.4 | 19.0 | 12.9 |

| 80+ | 6.7 | 8.1 | 7.7 | 8.1 | 8.9 | 7.6 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 56.4 | - | 53.2 | - | 53.4 | - |

| Female | - | 43.6 | - | 46.8 | - | 46.6 |

| Insurance Status | ||||||

| None | 5.9 | 5.9 | 3.8 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 3.5 |

| Private | 66.9 | 82.4 | 73.7 | 77.7 | 76.6 | 75.7 |

| Any Medicaid | 1.9 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 2.7 |

| Medicare Only | 14.7 | 1.5 | 6.4 | 3.7 | 10.8 | 7.7 |

| Other/ Unknown | 10.6 | 7.1 | 12.7 | 14.7 | 9.7 | 10.4 |

| Approved Residency Training | ||||||

| No/Unknown | 35.8 | 43.4 | 50.4 | 45.3 | 48.2 | 51.3 |

| Yes | 64.2 | 56.6 | 49.6 | 54.7 | 51.8 | 48.7 |

| Histology | ||||||

| Malignant, NOS | 27.3 | 33.0 | 38.0 | 31.4 | 38.6 | 40.2 |

| Superficial spreading | 48.4 | 46.4 | 38.1 | 47.1 | 38.0 | 41.5 |

| Nodular | 10.2 | 11.0 | 10.5 | 9.2 | 11.1 | 8.3 |

| Lentigo maligna | 6.7 | 2.8 | 9.5 | 5.9 | 6.8 | 3.8 |

| Desmoplastic | 2.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 2.3 |

| Other | 4.5 | 6.0 | 3.5 | 6.0 | 5.1 | 4.0 |

| Historic Stage | ||||||

| Localized | 90.7 | 90.0 | 85.1 | 92.0 | 84.2 | 86.5 |

| Regional | 9.3 | 10.0 | 14.9 | 8.0 | 15.8 | 13.5 |

| Tumor Depth | ||||||

| < 0.40 mm | 20.9 | 20.8 | 13.8 | 20.0 | 18.6 | 20.8 |

| 0.40 to 0.69 mm | 26.8 | 23.1 | 22.5 | 23.3 | 21.7 | 23.9 |

| 0.7 to 1.00 mm | 13.1 | 18.2 | 19.2 | 9.9 | 19.1 | 15.2 |

| 1.01 to 9.90 mm | 30.5 | 28.8 | 36.8 | 40.0 | 33.8 | 32.6 |

| Unknown | 8.7 | 9.1 | 7.7 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 7.5 |

| Positive Nodes | ||||||

| None Examined | 85.8 | 82.7 | 76.6 | 79.2 | 60.4 | 59.7 |

| All Negative | 10.5 | 11.6 | 17.3 | 18.7 | 33.6 | 33.9 |

| 1-3 | 2.1 | 5.7 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 5.4 | 5.9 |

| 4+ | 1.6 | 0 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.5 |

| At least one positive | 0 | 0 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Vital Status (through 2007) | ||||||

| Alive at last contact | 66.0 | 84.5 | 64.0 | 78.2 | 79.0 | 86.3 |

| Dead | 34.0 | 15.5 | 36.0 | 21.8 | 21.0 | 13.7 |

Treatment

The primary treatment for local or regional melanoma was surgery (Table 2). A substantial increase in lymph node sampling occurred over the time period (p<0.0001). The use of sentinel node biopsy increased significantly between 1995 and 2001(p<0.0001). In 1995, 5.1% of men and 9.2% of women had sentinel node biopsies compared to about one-third of patients diagnosed in 2001. The surgical margins were abstracted from pathology report or if not stated there, recorded from the operative report. Surgical margins were not stated or unknown for nearly 40% of men diagnosed in 1995 and 42% of women; this dropped to 15%, for men (p<0.0001) and 13% for women in 2001 (p<0.0001). Tumor margins increased more for men than women over time, although the percentage of patients with margins of 2 cm or greater increased in1996 and decreased in 2001.

Table 2.

Weighted Percent Distribution of Therapy Given by Year of Diagnosis for Non-distant Skin Melanoma

| 1995 | 1996 | 2001 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Surgery | ||||||

| No Cancer-Directed | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 |

| Local Excision | 20.4 | 17.6 | 14.1 | 9.7 | 7.0 | 9.4 |

| Biopsy/gross excision margins < 1 cm |

9 | 12.2 | 6.9 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 3.9 |

| Local thru Wide/radical excision |

70.6 | 70.1 | 77 | 84.4 | 86.7 | 85.9 |

| Major Amputation | 0 | 0 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.6 |

| Surgery, NOS | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| Technique of Lymph Node Dissection | ||||||

| No LND | 85.8 | 82.7 | 76.6 | 79.2 | 60.4 | 59.7 |

| Traditional | 5.9 | 6.6 | 10.9 | 4.2 | 4.7 | 3.7 |

| Any Sentinel | 5.1 | 9.2 | 10.7 | 16.4 | 32.3 | 35.3 |

| Technique Unknown | 3.2 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 2.6 | 1.3 |

| Margins of Surgical Excision | ||||||

| <1.0 cm | 35.2 | 30.2 | 30.5 | 34.1 | 22.6 | 28.0 |

| >1.0 - 2.0 cm | 15.1 | 16.9 | 20.5 | 18.4 | 20.2 | 18.0 |

| >2.0 cm | 6.2 | 8.9 | 13.1 | 14.9 | 7.3 | 5.6 |

| Margins clear, NOS | 0 | 0 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 32.9 | 32.1 |

| Tumor at margin | 4.1 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 3.2 |

| Not stated/Unknown | 39.4 | 42.4 | 30.4 | 27.6 | 14.6 | 13.2 |

| Chemotherapy/Immunotherapy | ||||||

| Yes | 3 | 7.2 | 10.8 | 4.9 | 6.3 | 4.9 |

| No | 92.2 | 90.2 | 83.3 | 91.4 | 92.9 | 94.6 |

| Unknown, refused | 4.8 | 2.6 | 5.9 | 3.7 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Radiation | ||||||

| Yes | 2.6 | 0 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| No | 97.4 | 100 | 97.9 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.2 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 |

Few patients received chemotherapy or immunotherapy and radiation was rare. More than 98% of patients with localized disease received surgery as their only treatment (data not shown). Twenty-seven percent, 35% and 22% of patients with regional disease received chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and/or immunotherapy in 1995, 1996 and 2001, respectively. In all years, interferon-α was the most frequent agent given for the treatment of regional melanoma. In 1995 slightly more than 26% of patients with regional stage melanoma received interferon alone or with other agents; this decreased to about 21% in 1996 and 2001. Although adjuvant therapy varied by stage it did not vary by sex within stage of disease.

Tumor Thickness

Patients with a tumor thickness of more than 1 mm were more likely to have a lymph node dissection (p<0.0001) (Table 3). The use of sentinel node biopsy increased significantly between 1995 and 2001 for all categories of reported tumor thickness and was significantly associated with tumor thickness (p<0.0001).

Table 3.

Weighted Percent Distribution Facility, Lymph Node Technique and Nodal Status by Tumor Depth and Year of Diagnosis for Non-distant Skin Melanoma

| 1995 | 1996 | 2001 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Depth | ≤0.69 | 0.70- 1.00 |

1.01- 9.90 |

Unk | ≤0.69 | 0.70- 1.00 |

1.01 9.90 |

Unk | ≤0.69 | 0.70- 1.00 |

1.01- 9.90 |

Unk |

| Number of cases | 106 | 40 | 93 | 24 | 310 | 111 | 269 | 62 | 305 | 123 | 238 | 54 |

| Technique of Lymph Node Dissection | ||||||||||||

| No LND | 96.4 | 90.0 | 64.0 | 81.3 | 98.0 | 84.6 | 53.8 | 80.8 | 90.8 | 50 | 22.7 | 76.4 |

| Traditional | 1.6 | 3.7 | 14.5 | 6.9 | 1.1 | 7.5 | 14.3 | 10.1 | 0.6 | 4.5 | 9.2 | 2.0 |

| Any Sentinel | 1.6 | 6.3 | 16.2 | 4.3 | 0.6 | 7.8 | 30.0 | 5.8 | 8.3 | 42.4 | 64.5 | 19.6 |

| Unknown | 0.4 | 0 | 5.3 | 7.5 | 0.3 | 0 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 0.2 | 3 | 3.6 | 2.1 |

| Nodal Status | ||||||||||||

| None Examined | 96.4 | 90.0 | 64.0 | 81.3 | 98.0 | 84.6 | 53.8 | 80.8 | 90.8 | 50.0 | 22.7 | 76.4 |

| All negative | 1.6 | 10.0 | 26.0 | 11.2 | 1.3 | 13.3 | 38.4 | 10.1 | 9.2 | 46.7 | 62.9 | 11.7 |

| Any positive | 2.0 | 0 | 10 | 7.5 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 0 | 3.3 | 14.5 | 12 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 1.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Margin Status | ||||||||||||

| ≤ 1.0 cm | 36.9 | 54.8 | 14.9 | 36.2 | 44.8 | 37 | 19.6 | 20.1 | 36.7 | 26.4 | 10.7 | 20.3 |

| >1.0 - 2.0 cm | 10.9 | 2.4 | 28.4 | 23.2 | 9.6 | 23.8 | 29.6 | 11.4 | 12.8 | 22 | 28.6 | 6.2 |

| >2.0 cm | 3.0 | 10.4 | 10.6 | 14.1 | 10.6 | 18.4 | 15.6 | 14.5 | 2.6 | 6.0 | 12.8 | 1.3 |

| Margins clear, NOS |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.2 | 4.4 | 3.1 | 0.8 | 31.4 | 30.4 | 34.9 | 33.3 |

| Tumor at margin | 4.7 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 0 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 6.6 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 3.6 | 4.6 |

| Not stated/ Unknown |

44.5 | 30.3 | 44.4 | 26.5 | 30.0 | 14.7 | 30.3 | 46.5 | 15.0 | 12.2 | 9.3 | 34.2 |

Recording of margin status increased over time and with increasing tumor thickness. Patients diagnosed in 2001 with thin melanomas (<0.7 mm) were more likely to have a margin of ≤ 1cm (37%) compared to those with tumors more than1.0 mm thickness (11%) (p<0.0001).

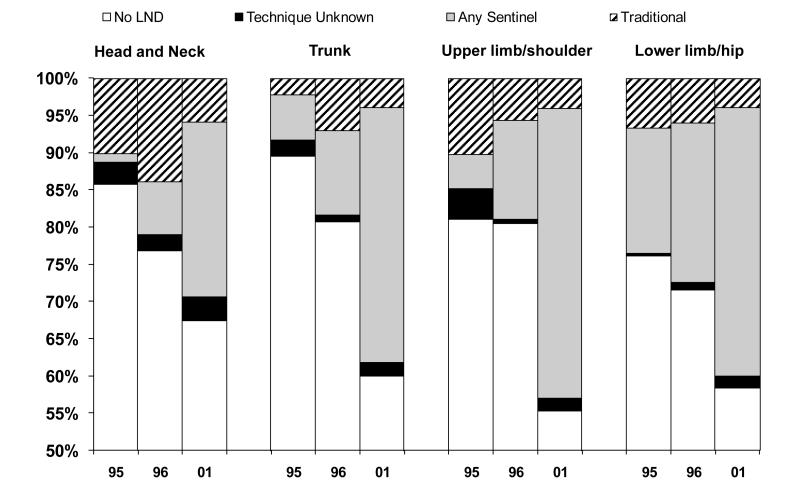

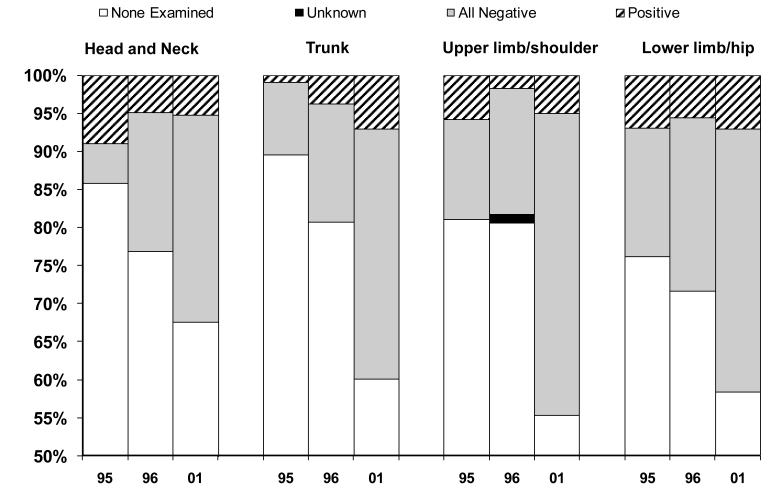

Site of Melanoma

The percent and technique of lymph node biopsy varied by the anatomic location of the melanoma. The percentage of patients who received lymph node dissection increased between 1995 and 2001 for all anatomic locations (p<0.03). However, the location of the melanoma influenced the technique of node biopsy (Figure 1). In 1995, patients with melanomas on the lower limbs or hips were somewhat more likely to have lymph node sampling than were patients with melanomas on other parts of the body and these patients were much more likely to have a sentinel node biopsy (p<0.04). By 2001 there were small differences in the use of sentinel node biopsy by location on the trunk, upper limbs and shoulder or lower limbs and hips; however, those with melanomas located on the head and neck were less likely to have a lymph node biopsy (p= 0.058), particularly using the sentinel node technique (p=0.005). Over time the percent of patients receiving lymph nodes biopsies increased (Figure 2). Despite this, only patients with melanoma on the trunk of the body had an increase in positive nodes; 1% in 1995 to 7% in 2001 (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Type of Node Biopsy by Location of Primary Cutaneous Melanoma and Year of Diagnosis

Note: Vertical axis begins at 50%

Figure 2.

Nodal Status by Location of Primary Cutaneous Melanoma and Year of Diagnosis

Note: Vertical axis begins at 50%

Health Care Factors

We examined tumor characteristics and treatment by the presence of an approved residency training program in the treatment facility (Table 4). Over time, the percentage of patients categorized histologically as “malignant melanoma, not otherwise specified,” increase, but was not different by sex. However, between 1995 and 2001 facilities with no approved residency training program had a significantly larger increase (p = 0.01). The number of nodes examined increased in both types of facilities, but those with a residency training program generally examined nodes more often (p<0.001). In each year of the study, facilities with a residency training program performed sentinel node biopsies more frequently than those without residency training (p<0.01). In 2001, nearly twice as many patients treated in facilities without a training program had a margin status not stated or unknown, 18% vs. 10% (p<0.01). In addition, more were recorded as “completely excised” without further specificity in hospitals with no residency training program (40%) than in hospitals with a program (25%) (p<0.0001).

Table 4.

Weighted Percent Distribution of Clinical Characteristics by Presence of an Approved Residency Training Program for Cases with Non-distant Melanoma

| 1995 | 1996 | 2001 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residency Training Approval | No/Unk* | Yes | No/Unk* | Yes | No/Unk* | Yes |

| Number of cases | 102 | 161 | 361 | 391 | 365 | 355 |

| Histology | ||||||

| Malignant melanoma, NOS | 33.2 | 27.6 | 37.7 | 32.3 | 43.3 | 35.4 |

| Superficial spreading | 44.3 | 49.6 | 39.7 | 44.8 | 34.1 | 45.0 |

| Nodular | 16.1 | 7.0 | 8.8 | 10.9 | 10.7 | 8.9 |

| Lentigo maligna melanoma | 3.6 | 5.8 | 9.6 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 4.6 |

| Desmoplastic | 0.5 | 2.9 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.4 |

| Other | 2.3 | 7.0 | 4.1 | 5.1 | 4.5 | 4.6 |

| Lymph Nodes Examined | ||||||

| None | 84.8 | 84.2 | 84.6 | 71.5 | 66.2 | 54.1 |

| 1 node | 3.0 | 5.2 | 2.3 | 8.4 | 9.8 | 11.8 |

| 2-5 nodes | 1.0 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 9.3 | 16.0 | 23.0 |

| 6-10 nodes | 2.6 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.0 |

| 11+ nodes | 5.6 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 5.8 | 2.4 | 6.3 |

| At least one, but number unknown | 3.1 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 1.5 |

| Other | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.3 |

| Technique of Lymph Node Dissection | ||||||

| No LND | 84.8 | 84.2 | 84.6 | 71.5 | 66.2 | 54.1 |

| Traditional | 9.6 | 4 | 8.7 | 6.9 | 3.6 | 4.9 |

| Any Sentinel | 1.7 | 10.3 | 6 | 20.1 | 28.6 | 38.7 |

| Technique Unknown | 4 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.3 |

| Margins | ||||||

| < 1.0 cm | 19.6 | 41.6 | 23.0 | 40.7 | 20.4 | 29.8 |

| >1.0 - 2.0 cm | 14.1 | 17.0 | 13.3 | 25.2 | 13.8 | 24.5 |

| >2.0 cm | 11.8 | 4.6 | 18.0 | 10.2 | 5.4 | 7.5 |

| Margins clear, NOS | 0 | 0 | 4.6 | 1.9 | 39.8 | 25.4 |

| Tumor at margin | 2.6 | 3.3 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.9 |

| Not stated/Unknown | 51.9 | 33.5 | 39.6 | 19.3 | 18.1 | 9.9 |

| Treatment | ||||||

| No treatment reported | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Surgery Only | 91.1 | 91.9 | 87.5 | 86.2 | 95.2 | 91.3 |

| Chemo/Immunotherapy Only | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 |

| Surgery and Chemo/Immunotherapy | 8.0 | 2.7 | 5.6 | 8.9 | 3.2 | 7.4 |

| Surgery and XRT | 0 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Surgery, XRT, and Chemotherapy | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.2 |

| Unknown | 0.8 | 3.7 | 5.3 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 0.4 |

Unknown

Survival

In a Cox proportional hazards model we examined cutaneous melanoma mortality for males and females separately adjusting for age, Charlson comorbidity score, tumor thickness, margin status, and year of diagnosis (Table 5). Mortality from melanoma for men increased significantly with a tumor thickness of 0.7 mm or greater and for women with a tumor thickness of great than 1 mm. Charlson score, margin status and year of diagnosis were not significantly related to melanoma-specific mortality for either men or women.

Table 5.

Hazards Ratio* for Death from Melanoma for Patients Diagnosed with Melanoma by Sex 1995, 1996 and 2001

| MALES | FEMALES | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazards | 95% CI | Hazards | 95% CI | |||||

| Ratio* | LL | UL | p-value | Ratio | LL | UL | p-value | |

| Age at Diagnosis | 0.06 | 0.97 | ||||||

| 1.01 | 1.0 | 1.03 | 1.0 | 0.98 | 1.02 | |||

| Charlson Score | 0.16 | 0.35 | ||||||

| 0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| 1+ | 1.5 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 0.5 | 0.09 | 2.4 | ||

| Tumor Thisckness | <0.0001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| <= 0.69 mm | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| 0.70 - 1.00 mm | 2.8 | 1.1 | 6.9 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 16.1 | ||

| 1.01 - 9.90+ mm | 7.9 | 3.8 | 16.5 | 18.8 | 4.2 | 85.3 | ||

| Unknown | 4.0 | 1.5 | 10.5 | 11.8 | 2.2 | 63.5 | ||

| Margins of Surgical Resection | 0.26 | 0.98 | ||||||

| Tumor at margin | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| 1+ cm | 0.5 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 5.1 | ||

| Margins clear, NOS + <1 cm | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 4.3 | ||

| Unknown | 0.6 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 5.5 | ||

| Year of Diagnosis | 0.37 | 0.13 | ||||||

| 1995 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| 1996 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 2.0 | ||

| 2001 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 4.8 | ||

Follow-up through December 2007

Adjusted for all variables in the table.

Discussion

This study offered an opportunity to examine trends in treatment, the use of adjuvant therapy and survival in a population-based sample of patients with local or regional cutaneous melanoma treated in communities throughout the US. As suggested by treatment guidelines, the primary therapy for both stages of melanoma was surgery. 3 However, the use of chemotherapy or immunotherapy, listed as an option in the guidelines, has not changed substantially over time for individuals diagnosed with regional stage melanoma. From the mid-1990s to the early 2000s the percentage of patients having sentinel lymph node biopsies quadrupled, demonstrating dissemination of this technique into community practice. Depth of tumor invasion continues to be a strong predictor of survival. However, there was no significant change in melanoma-specific mortality in patients diagnosed in 1995, 1996 and 2001.

Margins

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines call for wide excision of cutaneous melanomas with clear margins of 1 to 2 cm, depending on tumor thickness.3 A meta-analysis of three randomized clinical trials comparing different surgical margins reported that the surgical margin around the primary melanoma should not be less than 1cm.9 A subsequent meta-analysis that included 2 additional randomized trials determined that there may be insufficient data to conclude that narrow margins are not inferior to wider margins.10 The percentage of patients with tumor margins not reported or unknown has decreased substantially over time, suggesting an increase in attention to margin status. By 2001, 86% of the patients had margin status recorded. However, only 26% of pathological margins were reported as being >1cm with another 25% ≤ 1 cm and 33% reported as being uninvolved, but not otherwise specified.

Thomas et al. reported that patients with melanomas of 2 mm or greater thickness had a significantly greater risk of locoregional recurrence if the melanoma had a margin of 1cm as compared to a margin of 3 cm.11 In the current study, we do not have data to examine recurrence, but in 2001 only 3.5% of patients with tumor thicknesses greater than 1 mm had margins of greater than 3 cm while 28.6% had margins of 1.01 cm to 2 cm.

Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy

The use of sentinel lymph node biopsy began in the early 1990s following development of the technique and publication of early results. 12,13 Sentinel lymph node biopsy increased between 1995-1996 and 2001 in all categories of tumor thickness that we examined. Although sentinel node biopsy is important in staging, a Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial analysis indicated that in patients with intermediate thickness primary melanomas, sentinel node biopsy was not associated with increased melanoma-specific survival when compared to the observation group.14 In the current study, we found that the tumor thickness and technique of lymph node biopsy were significantly associated with melanoma mortality in both men and women. There was also a strong correlation between sentinel node biopsy and tumor thickness. However, the association cannot be attributed to the technique of nodal sampling because patients with thicker tumors, and therefore more likely to die, were also significantly more likely to have traditional sampling.

Carlson et al. reported that patients with melanoma of the head or neck and with increased tumor thickness were more likely to have false negative sentinel lymph nodes.15 We found that patients with melanoma of the head and neck were less likely to have a sentinel node biopsy than were patients with melanoma of other sites. It is possible that physicians chose not to use sentinel lymph node biopsies because of the more variable lymphatic drainage patterns for tumors of the head and neck.

Likelihood of Positive Nodes

Investigators have reported an increase in positive nodes with increased tumor thickness.14,16 In this population-based sample, we found that as tumor thickness increased, the percent of patients who had lymph nodes sampled increased, as did the percentage with positive nodes.

Non-surgical Therapy

For patients with limited resectable disease (more than 1 mm thick and negative lymph nodes) the NCCN guidelines suggest interferon-α as an option and advise that interferon-α or radiation should be considered for patients with positive nodes.3 A meta-analysis published in 2002 reported that the randomized clinical trials did not support a “clear benefit” for interferon-α.17 Controversy still surrounded the use of interferon-α in the treatment of stage IIb and III as evidenced by a point-counterpoint published in early 2008.18,19 The lack of consensus regarding the use of interferon-α was highlighted by the geographic variation in our data. In one geographic area no patient in any of the 3 years received interferon-α while in another area 11% received interferon-α in 1995, although this decreased to 6% in 2001. However, a 2010 meta-analysis of interferon-α. studies in high-risk patients showed a significant increase in disease free and overall survival.20 These findings may influence clinical practice moving it towards a consensus.

Despite the guidelines suggesting that radiation should be considered for patients with positive lymph nodes, in all 3 years only about 1% of patients received radiation. This low rate of use appears to reflect some concern regarding the benefit. Several registries reported no melanoma patient with localized or regional disease was given radiation in any of the three years, while in the registry reporting the highest use only about 3.5% of patients received radiation in 1995 and 1996.

Health Care Facility

Facilities with approved residency training programs generally treated melanoma patients more aggressively than did facilities without such programs, performed more lymph node dissection, used the sentinel node biopsy technique, recorded specifics on margin status measurements, and were more aggressive in their use of non-surgical therapy. Pennie et al. reported that Medicare patients diagnosed with melanoma by a dermatologist had earlier stage disease at diagnosis and better survival.21 However, we were unable to determine the specialty of the residency program and it is likely that the majority of these programs were not dermatologic residencies.

Survival

A study of survival following cutaneous melanoma in England and Wales found survival increased from the late 1980s to the late 1990s, but men had poorer survival than women.22 A long-term follow-up study in Germany reported that men, older age, melanoma of the head or truck, as well as patients with tumors of higher pT and pN had poorer survival.23 In our population-based study, men also had poorer survival. We found that tumor thickness was associated with an increased mortality from cutaneous melanoma. Although being treated in a facility with a residency training program was associated with more aggressive therapy, it was not associated with survival in the multivariate analyses and was excluded from the final model. Perhaps the lack of association in the model was due to patients with poorer prognostic factors selecting or being referred to facilities with residency training programs. An analysis of melanoma patients in the SEER-Medicare data diagnosed between 1988 and 1999 reported patients with a higher stage, increased tumor thickness, certain histologies, tumor locations, earlier year of diagnosis, older age, male sex, and increased comorbidity score were at an increased risk of cancer mortality.24 However, we cannot directly compare these two studies as we included only white adult patients, diagnosed in the mid-1990s and early 2000s with localized or regional disease. The SEER-Medicare study included patients age 65 or older from all racial/ethnic groups.

Limitations

We do not have information on patient preference for therapies. It is possible that some patients preferred a wider excision with the hope of avoiding adjuvant therapy or additional surgery. In addition, we used the best available data for margin status which might have been based on clinical assessment and influenced our findings by increasing the apparent margins. Recent research indicates that physicians do a poor job of estimating size of margins of tumor based on visual inspection. Clausen and Brady reported a discrepancy between clinical and pathological margins with pathologic margins being 90% of the clinical margins.25 We also do not know the specialty of diagnosing and/or treating physician. This might have influenced the therapy selected. However, this is a population-based sample of patients being treated in the community throughout the United States and should provide a picture of therapy, trends in that therapy over 7 years, and survival through 2007.

Conclusion

With the exception of nodal sampling and margin status, therapy for localized and regional melanomas has not changed significantly between 1995 and 2001. The use of adjuvant therapy in melanoma patients was minimal and has, in fact, decreased over time. It is clear that a consensus on the use of such therapies for these patients treated in a community setting has not been reached. In addition, after adjusting for demographic, tumor characteristics and surgical margins, mortality from melanoma has not changed. Future research should include a focus on the reasons for the continuing poorer survival among men and on clinical trials for patients with melanoma to identify the appropriate therapy.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the work of the SEER Cancer Registries. This research would not be possible without their efforts.

Funding: N01-PC-35133, N01-PC-35135, N01-PC-35141, N01-PC-35136, N01-PC-35137, N01-PC-35138, N01-PC-35139, N01-PC-35142, N01-PC-35143, N01-PC-35145, N01-PC-54402, N01-PC-54404, N01-PC-54405

Footnotes

The authors have no commercial associations, current and over the past 5 years, that might pose a conflict of interest.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, Edwards BK, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2008. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2011. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008/, based on November 2010 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures 2011. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp.

- 4.Kirkwood JM, Strawderman MH, Ernstoff MS, et al. Interferon alfa-2b adjuvant therapy of high-risk resected cutaneous melanoma: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial EST 1684. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:7–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirkwood JM, Ibrahim JG, Sondak VK, et al. High- and low-dose interferon alfa-2b in high-risk melanoma: first analysis of intergroup trial E1690/S9111/C9190. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2444–58. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.12.2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkwood JM, Ibrahim J, Lawson DH, et al. High-dose interferon alfa-2b does not diminish antibody response to GM2 vaccination in patients with resected melanoma: results of the Multicenter Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Phase II Trial E2696. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1430–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/melanoma/HealthProfessional/page5.

- 8. http://seer.cancer.gov/about/

- 9.Haigh PI, DiFronzo LA, McCready DR. Optimal excision margins for primary cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Surg. 2003;46:419–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mocellin S, Pasquali S, Nitti D. The impact of surgery on survival of patients with cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg. 2011;253:239–243. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318207a331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas JM, Newton-Bishop J, A’Hern R, et al. Excision margins in high-risk malignant melanoma. NEJM. 2004;350:757–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morton D, Cagle I, ong J. Intraoperative lymphatic mapping and selective lymphadenectomy: technical details of a new procedure for clinical stage I melanoma. Presented at the 42nd Annual meeting of the Society of Surgical Oncology; Washington, DC. May 20-22, 1990; er al. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morton DL, Wen DR, Wong JH, et al. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch Surg. 1992;127:392–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420040034005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy or observation in melanoma. NEJM. 2006;355:S1207–1317. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlson GW, Page AJ, Cohen C, et al. Regional recurrence after negative sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Ann Surg. 2008;248:378–386. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181855718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong SL, Kattan MW, McMasters KM, et al. A nomogram that predicts the presence of sentinel node metastasis in melanoma with better discrimination than the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:282–288. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lens MB, Dawes M. Interferon alfa therapy for malignant melanoma: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1818–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirkwood JM, Tarhini AA, Moschos SJ, Panelli MC. Adjuvant therapy with high-dose interferon α 2b in patients with high-risk stage IIB/III melanoma. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;5:2–3. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bajetta E. Adjuvant use of interferon α2b is not justified in patients with stage IIb/III melanoma. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;5:4–5. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mocellin S, Pasquali S, Rossi CR, Nitti D. Interferon alpha adjuvant therapy in patients with high-risk melanoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JNCI. 2010;102:493–501. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pennie ML, Soon SL, Risser JB, Veledar E, Culler SD, Chen SC. Melanoma outcomes for Medicare patients: association of stage and survival with detection by a dermatologist vs a nondermatologist. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:488–94. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rachet B, Quinn MJ, Coleman MP. Survival from melanoma of the skin in England and Wales up to 2001. BJC. 2008;99:547–59. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hohnheiser AM, Gefeller O, Gohl J, Schuler G, Hohenberger W, Merkel S. Malignant melanoma of the skin: Long-term follow-up and Time to first Recurrence. World J Surg. 2011;35:580–589. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0859-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reyes Ortiz CA, Freeman JL, Kuo YF, Goodwin JS. The influence of marital status on stage at diagnosis and survival of older persons with melanoma. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:892–8. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.8.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clausen SP, Brady MS. Surgical margins in patients with cutaneous melanoma – assessing the adequacy of excision. Melanoma Res. 2005;15:539–542. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200512000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]