Abstract

Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis is exploited clinically for the treatment of hematologic malignancies. Determining required molecular events for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis will identify resistance mechanisms and suggest strategies for overcoming resistance. In the current study, we found that glucocorticoid treatment of WEHI7.2 murine thymic lymphoma cells increased the steady state [H2O2] and oxidized the intracellular redox environment prior to cytochrome c release. Removal of glucocorticoids after the H2O2 increase resulted in a 30% clonogenicity; treatment with PEG-CAT increased clonogenicity to 65%. Human leukemia cell lines also showed increased H2O2 in response to glucocorticoids and attenuated apoptosis after PEG-CAT treatment. WEHI7.2 cells that overexpress catalase (CAT2, CAT38) or are selected for resistance to H2O2 (200R) removed enough of the H2O2 generated by glucocorticoids to prevent oxidation of the intracellular redox environment. CAT2, CAT38 and 200R cells showed a 90–100% clonogenicity. The resistant cells maintained pERK survival signaling in response to glucocorticoids while the sensitive cells did not. Treating the resistant cells with a MEK inhibitor sensitized them to glucocorticoids. These data indicate that:1) an increase in H2O2 is necessary for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in lymphoid cells; 2) increased H2O2 removal causes glucocorticoid resistance; and 3) MEK inhibition can sensitize oxidative stress resistant cells to glucocorticoids.

Keywords: hydrogen peroxide signaling, glucocorticoids, lymphoma, ERK, MEK, apoptosis, catalase, glutathione

Introduction

Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of lymphocytes is a physiological process that has been exploited for clinical use. Although glucocorticoid-induced lymphocyte apoptosis is a paradigm for the description of the apoptotic process, the molecular events required during the signaling phase are still not well understood. Defining the required signals in tumor cells is of clinical importance because the signaling phase is the most likely source of drug resistance in the treatment of hematologic malignancies.

Glucocorticoids induce lymphocyte apoptosis via the intrinsic pathway. During the signaling phase, glucocorticoids bind to a cytosolic receptor. The steroid-receptor complex translocates to the nucleus where it acts as a transcriptional activator and repressor of multiple genes in signaling networks [1,2]. Progress has been made in identifying events that occur during glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis signaling (recently reviewed in [1,2]). The list of events is extensive and ranges from alterations in proteins at the transcriptional level [2,3], to changes in metabolic events such as sphingomyelinase activation [4] and Ca2+ fluxes [5]. Additional work has identified survival pathways, such as extracellular signal-regulated kinase (pERK) signaling, that when upregulated, interfere with glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis [6]. The complex interaction of multiple genetic and metabolic signaling events determines the decision to undergo apoptosis [1,6]. The signals impinge on the mitochondria resulting in the release of cytochrome c, which commits the cell to apoptosis [7]. Bcl-2 family members appear to control the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria [8,9]. Induction of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member, Bim [2,3,10] at the transcriptional level is a required event. During the execution phase, cytochrome c binds the apoptosome catalyzing the activation of the caspases [7]. Caspases then degrade cellular proteins. The molecular events that are required during the execution phase are fairly well established; however, work is still needed to determine which molecular events are required signals for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis.

Several studies have implicated reactive oxygen species (ROS) in glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis signaling. Most of these studies used cultured immature thymocytes. This model has significant limitations for determining signaling events. Immature thymocytes die in culture; glucocorticoids accelerate the death (e.g. [11,12]). Generally, the studies showed that addition of exogenous antioxidant defense enzymes or chemical antioxidants delay glucocorticoid-induced thymocyte apoptosis (reviewed in [11,13]). During the execution phase of apoptosis, one of the caspase targets is p75 in complex I of the mitochondrial electron transport chain [14]. Cleavage of this protein results in an increase in ROS [14]. Inhibition of events in the execution phase can result in delayed apoptosis or a switch to an alternate form of cell death such as necrosis. Thus, the finding that antioxidants delay glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in immature thymocytes does not discriminate between removal of an ROS signal and a delay in execution phase events.

To act as a signal, ROS need to increase prior to apoptosis commitment. Several studies have looked for an ROS increase shortly after glucocorticoid treatment. Some studies have shown an increase in ROS or lipid peroxidation, as a measure of oxidative damage, in thymocytes [11,15–17] or S49.1 cells [18] shortly after glucocorticoid treatment. This is consistent with ROS acting as signaling molecules. None of these studies addressed which ROS was critical. Other studies either failed to find an increase in ROS [2,18] or measured decreased ROS after steroid treatment [19]. Further, one recent study suggests that the depletion of glutathione is the required event [20]. Although they did not specifically test glucocorticoids, Franco et al. conclude that ROS play a “bystander” role during apoptosis via the intrinsic pathway independent of inducing agent [20]. These contradictory results combined with the limitations of the immature thymocyte cultures do not allow us to determine whether ROS are critical signals for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in tumor cells.

In this study, we used a combination of WEHI7.2 murine thymic lymphoma tissue culture cells and human leukemia cell lines to determine whether ROS are a necessary signal for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in tumor cells. Defining the role of ROS in glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of lymphoma cells has potential clinical implications. Chronic inflammation is a risk factor for the development of lymphoma [21]. Immune cells at the site of chronic inflammation have an increased exposure to ROS. Chronic exposure to ROS results in cells that are resistant to ROS via upregulation of antioxidant defenses [22,23]. An increased ability to remove ROS could be a source of resistance to glucocorticoids during lymphoma treatment. Previously, we found that WEHI7.2 cells overexpressing catalase or thioredoxin show delayed loss of viable cells from glucocorticoid-treated cell cultures [13,24]. Although these data are consistent with ROS playing a critical role, we did not directly measure ROS or determine whether glutathione modulation could explain our earlier observations. In the current study, by using more discriminating ROS measurement tools, we found that: 1) H2O2 is a necessary signal for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis; 2) increased H2O2 removal causes glucocorticoid resistance; and 3) use of MEK inhibitors can overcome glucocorticoid resistance in cells that are oxidative stress resistant.

Materials and methods

Reagents and drug treatments

MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK1) inhibitor, PD98059, was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA) and used at a concentration of 50 μM. 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) was purchased from Invitrogen (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). All additional drugs and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted. Polyethylene glycol-conjugated catalase (PEG-CAT) was added at a concentration of 100 U/ml. For WEHI7.2 cells, response to dexamethasone was determined by incubating cells in a final concentration of 1 μM dexamethasone in an ethanol vehicle (final concentration of ethanol = 0.01%) or an equivalent amount of vehicle alone. For Molt-4 and Jurkat cells, response to dexamethasone was determined by incubating cells in dexamethasone at the respective EC50 concentrations or an equivalent amount of DMSO. Dexamethasone treatment was continuous unless otherwise stated.

Protein Measurements

Cellular protein was measured in clarified lysates using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell culture, development of variants and colony formation

The mouse thymic lymphoma WEHI7.2 parental cell line [25] and variants overexpressing rat catalase (CAT2, CAT38) [13], vector only (Neo3) [13] or selected for resistance to 200 μM H2O2 (200R) [26] were maintained in suspension cultures, as described in the indicated references. Any variant normally grown in the presence of drug was cultured in the absence of drug one week prior to each experiment. Molt-4 cells and Jurkat cells were obtained from Dr. Lisa Rimsza and Dr. Terry Landowski (University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ), respectively. Cells were maintained in suspension in RPMI 1640 (Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (ATCC, Manassas, VA); 2 mM glutamine (Invitrogen); and 50 U/ml of each of penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cell cultures were incubated in a humidified 5% CO2 environment at 37°C.

Relative colony formation was determined by treating the cells for 12 h with 1 μM dexamethasone or vehicle control, washing the cells twice with medium in the absence of dexamethasone and plating in MethoCult M3134 (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) in the absence of dexamethasone. MethoCult M3134 was reconstituted with conditioned DMEM medium (Invitrogen) with 10% calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT) using the manufacturer’s protocol. Cultures were incubated for 4 days under normal culture conditions and colonies counted. A colony was defined as a cluster of ≥ 40 cells.

Annexin V binding measurements

The fraction of apoptotic cells after dexamethasone treatment was determined using the apoptosis detection kit (R & D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. For some measurements, Alexa Fluor 488-labeled annexin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was substituted for the FITC-labeled annexin and 1 μg/ml 7-AAD was substituted for the propidium iodide that is supplied with the kit. Cellular fluorescence was measured and analyzed using a FACScan flow cytometer with CELLQuest software (Becton Dickenson, San Jose, CA) or an EPICS XL-MCL flow cytometer (Coulter, Corp., Miami, FL). Numbers less than 5% different are considered within the error of the machine after calibration for this assay. Cells that were positive for annexin V staining and negative for propidium iodide or 7-AAD staining were considered apoptotic. Ten thousand cells were analyzed per sample.

Caspase 3 activity

Caspase 3 activity was measured using a colorimetric assay that depends on the cleavage of the synthetic caspase 3 specific substrate, Ac-DEVD-p-nitroanilide (pNA) (BIMOL International LTD, Bangkok, Thailand). Briefly, cells were lysed in: 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 100 mM NaCl; 1 mM EDTA; 0.01% Triton X-100 by sonication. The samples were clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min. An aliquot of the supernatant then was incubated in: 10 mM PIPES, pH 7.4; 2 mM EDTA; 0.01% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate hydrate (CHAPS); 5 mM DTT; 200 μM Ac-DEVD-pNA for 2 h and the absorbance at 405 nm measured using a SynergyHT plate reader (Bio Tek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT). Activity was normalized for cellular protein measured as described above. Caspase 3 activity in the presence of dexamethasone was corrected for that in vehicle-treated cells for each treatment.

MTS measurements

Molt-4 and Jurkat cells were grown in a range of dexamethasone concentrations for 48 h. Relative cell number was measured using the Cell Proliferation Kit II (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Relative cell number in the presence or absence of PEG-CAT and dexamethasone was also determined after incubation in the indicated compounds for 24 h (WEHI7.2 cells) or 48 h (Molt-4 and Jurkat cells) using this method. For both types of assays, the plates were read at 490 nm using a Synergy HT plate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments). Fraction control absorbance was calculated as previously described [27]. EC50 was defined as the concentration at which the absorbance was 50% that of the control.

DCF Measurements

Cells were washed with DMEM containing 0.5% calf serum, then incubated 2 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified environment in 0.5% serum DMEM containing 20 μM 5-(and-6)-carboxy-2′7′dichlorofluorescin diacetate (cDCFH-DA)(C-369) or 2′7′dichlorodihydrofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA)(D-399) (Molecular Probes). Both dyes are taken into the cell and the acetate groups removed. cDCFH will fluoresce once the acetate groups are removed, but DCFH fluoresces only in the presence of ROS [28]. Thirty minutes before analysis, 5 μg/ml propidium iodide was added to the medium. Cells were analyzed using a FACScan flow cytometer with Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson). Ten thousand cells were analyzed per sample. Cells that were propidium iodide positive were excluded from analysis. Fluorescence due to DCF was corrected for the relative cDCFH fluorescence to account for differences in dye uptake between the dexamethasone and vehicle treated cells. Plotted DCF fluorescence values were corrected for the DCF fluorescence in the vehicle-treated cells.

Immunoblots

Proteins from clarified total cell lysate were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes as previously described [13]. Blots were probed as previously described [13] using antibodies to the following: phospho-p44/42 (Erk1/2)(Thr202/Tyr204); p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Cell Signaling Technology); and β-actin (AbCam, Cambridge, MA). Proteins were detected by incubating with horseradish peroxidase-linked goat anti-rabbit Ig (Cell Signaling Technology) or anti-mouse Ig (Millipore, Billerica, MA or Cell Signaling Technology), as appropriate, and visualized using chemiluminescence reagents as previously described [13]. To visualize multiple bands on the same blot, blots were stripped with Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Pierce) before being probed with a new antibody.

Oxidized proteins

Oxidized proteins were measured using the Oxyblot Protein Oxidation Detection Kit (Chemicon International, Billerica, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, protein carbonyl groups were derivitized by dinitrophenylhydrazine, separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto PVDF membrane. Derivatized proteins were detected using immunoblotting and chemiluminescence.

Glutathione and glutathione disulfide

Glutathione and glutathione disulfide were measured using the Bioxytech GSH/GSSG 412 kit (Oxis Research, Portland, OR) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Values were normalized to cellular protein. Redox potential (Eh) was calculated using a simplified Nernst equation, Eh (in mV) = E0 + 30 log ([GSSG]/[GSH]2), using molar concentrations of GSH and GSSG and E0 = −264 mV for pH 7.4 [29]. Cell volume was measured using a ViCell 1.01 (Beckman, Fullerton, CA).

roGFP2 measurements

The redox sensitive GFP plasmid, p-EGFP-N1/roGFP2 [30] (a gift from Dr. S. James Remington) was electroporated into WEHI7.2 and variant cells using the Amaxa Nucleofactor II (Amaxa GmbH, Germany). Cells were grown in phenol-red free DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% calf serum for 24 h, then treated with 1 μM dexamethasone or vehicle control for 12 h. Cells were imaged using the DeltaVision Restoration Microscopy System (Applied Presicion, Inc., Issaquah, WA) using excitation lines at 407 nm and 488 nm and a 510/21 nm emission filter. Data were collected and processed using Scion Image (Scion, Frederick, MD). Images were corrected for background fluorescence by subtracting the intensity of a nearby cell-free region. Fluorescence excitation ratios were then calculated by dividing the integrated intensities of the cells at the different excitation wavelengths using the formulas described in Hanson et al. [30]. Between 20 and 35 cells were analyzed per cell variant per treatment.

Amplex® Red measurements

The rate of H2O2 efflux was determined by measuring the rate of oxidation of the fluorogenic indicator Amplex® Red (Invitrogen) in the presence of horseradish peroxidase. Briefly, cells were resuspended in phenol red-free DMEM (Invitrogen) with 10% calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories) containing 50 μM Amplex® Red and 0.1 unit/ml horseradish peroxidase. The rate of increase in fluorescence (Ex: 485/Em: 510) was measured using a SynergyHT plate reader (Bio Tek Instruments, Inc.) over a 4 h period. Rates were normalized to cellular protein measured as described above. In some instances, the medium was incubated in the presence of catalase (5U/200 μl) before the addition of the Amplex® Red reagent.

Steady state [H2O2] concentration

Steady state [H2O2] was measured using the catalase inactivation assay of Royall et al. [31]. Briefly, cells were treated for 12 h with 1μM dexamethasone or vehicle control and then 20 mM 3-amino-2,4,5-triazole was added to the cultures. Samples were harvested at intervals over a 6 h timecourse and catalase activity measured in each sample as previously described [13]. Activity was normalized for cellular protein, measured as described above. The rate of catalase inactivation was used to calculate steady state [H2O2] [31]. In the presence of H2O2, aminotriazole at a concentration of 20 mM was sufficient to completely inactivate catalase in 6 h indicating that 20 mM was saturating under these conditions.

Quantitation of gel bands, calculations and statistics

Films were scanned (CanoScan100F, Cannon) and the resulting TIFFs imported into Photoshop (Adobe Systems Incorporated, San Jose, CA). The image was inverted and the signal quantitated by determining the number of pixels in an equal area of each lane (http://lukemiller.org/journal/2007/08/quantifying-western-blots-without.html). For the Oxyblots, the area included multiple bands; for ERK and actin the area included only the band of interest. Background signal from gel lanes containing non-derivatized proteins (Oxyblot) or no proteins (all other blots) was subtracted. Signals in dexamethasone-treated cells were corrected for relative actin in the control-treated cells for each variant to correct for differences in gel loading. For the Oxyblots, the signals were normalized to the oxidized protein signal in control WEHI7.2 cells. For pERK, values were normalized for either control WEHI7.2 values or Neo3 values as appropriate. To calculate repression, values in control-treated cells were subtracted from values in dexamethasone-treated cells.

Means were compared using ANOVA or student’s t-tests, where appropriate, with the algorithms in Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA). Means were considered significantly different when p ≤ 0.05. To compare repression of pERK, mean repression and a 95% confidence interval were then calculated [32]. Repression was considered significant if the 95% confidence interval did not contain 0 [32].

Results

ROS increase prior to measures of apoptosis

To meet the criterion of a signaling event, ROS must increase prior to the release of cytochrome c. Previously, we found that in the WEHI7.2 cells cytochrome c is detectable in the cytosol at 24 h after the addition of dexamethasone, a synthetic glucocorticoid [13]. In case our ability to measure cytochrome c release was not sensitive enough to delimit the signaling phase, we established the sequence of additional apoptotic events in the WEHI7.2 cells that depend on cytochrome c release. As shown in Figure 1, annexin-positive cells were significantly increased after a 16 h-dexamethasone treatment. Caspase 3 activity was also increased over that in control cells by 16 h after the addition of dexamethasone. These data suggest that events occurring prior to 16 h are signaling events in this model system. ROS, as measured by DCF fluorescence, increased over that in vehicle-treated cells by 8 h post dexamethasone treatment. ROS due to dexamethasone continued to increase up to 12 h and remained high through 24 h. This increase in DCF fluorescence was not due to differential dye uptake because the values were corrected for dye uptake for each treatment. These data indicate that ROS increased prior to any other measures of apoptosis including cytochrome c release. This sequence of events is consistent with an increase in ROS functioning as a signaling event. Based on these measurements, we chose 12 h for subsequent measurements of signaling events.

Figure 1.

Dexamethasone treatment increases ROS prior to measures of apoptosis in WEHI7.2 cells. Timecourse showing the increase DCF fluorescence (◆) relative to the % apoptotic cells (●), caspase 3 activity (■) and cytochrome c release [13] in WEHI7.2 cells after the addition of dexamethasone at t = 0. DCF fluorescence values have been corrected for relative dye uptake and DCF fluorescence in vehicle-treated cells. Cells that were annexin V positive and propidium iodide negative were considered apoptotic. These values have been corrected for annexin V positive cells in vehicle-treated cells. Caspase 3 activity values have been corrected for that in vehicle-treated cells. Values are the mean ± S.E.M (n = 3 or 6). In some cases, the error bars are contained within the symbols. * denotes significantly different from 0 h values (p ≤ 0.05). A partial timecourse of the appearance of annexin V positive WEHI7.2 cells has been published previously [69].

Dexamethasone treatment increases intracellular H2O2 and alters the redox environment

DCF is not specific for a particular ROS [33]. To determine whether dexamethasone treatment increased H2O2, we used the catalase inactivation assay of Royall et al. to specifically measure H2O2 [31]. In the assay, aminotriazole binds to and irreversibly inactivates catalase after catalase has bound one molecule of H2O2 [31]. Due to the molar ratio of catalase and H2O2 when aminotriazole binds, the steady state H2O2 concentration in the cell can be calculated from the rate of catalase inactivation when aminotriazole is saturating [31]. Therefore, we first identified a concentration of aminotriazole that was saturating in the WEHI7.2 cells. Addition of 20 mM aminotriazole was able to reduce the catalase activity to undetectable levels in 6 h under conditions where H2O2 was produced (data not shown). This indicated that 20 mM aminotriazole was sufficient for these experiments. The next step was to measure the steady state H2O2 concentration ([H2O2]ss) in the presence and absence of dexamethasone 12 h after the addition of drug. As shown in Figure 2A, dexamethasone treatment increased the rate of catalase inactivation. In the absence of dexamethasone, the [H2O2]ss was 20.5 ± 5.5 pM. Twelve hours after the addition of dexamethasone, the [H2O2]ss was 55.5 ± 4.7 pM. These data indicate that dexamethasone treatment increased the intracellular [H2O2]ss.

Figure 2.

Dexamethasone treatment increases intracellular hydrogen peroxide and alters the redox environment in WEHI7.2 cells. A. Plot of the ℓn of catalase activity in the presence of 20 mM aminotriazole in control (●) and dexamethasone-treated (◆) cells. Aminotriazole was added 12 h after the addition of dexamethasone. Values represent the mean ± S.E.M. (n=3). In some cases the error bars are contained within the symbol. [H2O2]ss was calculated from the mean rate of catalase inactivation. This is a representative experiment which has been replicated. [H2O2]ss values are the mean of 7–8 rate determinations. B. Measurement of oxidized and reduced GFP 12 h after the addition of dexamethasone in control and dexamethasone-treated WEHI7.2 cells. Panels show reduced GFP (green), oxidized GFP (red) and a merged image of a representative control and dexamethasone (DEX) treated cell. Values are the mean oxidized or reduced roGFP2 ± S.E.M. (n = 25–30).

To determine whether the H2O2 produced after dexamethasone treatment alters the redox environment, we used a roGFP2 probe that contains GFP with redox active cysteines [30]. The oxidized and reduced GFP excite at different wavelengths, allowing the calculation of the relative % oxidized and reduced for each cell [30]. The roGFP2 measurements most closely reflect the relative oxidation of the glutathione disulfide (GSSG)/glutathione (GSH) redox couple [34]. Figure 2B shows an image of the relative amount of oxidized and reduced roGFP2 in a representative control cell and a cell treated for 12 h with dexamethasone. In the control cells, 90.97 ± 0.05% of the roGFP2 was reduced and 9.03 ± 0.05% was oxidized. In contrast, in the presence of dexamethasone, only 10.05 ± 2.08% of the roGFP2 molecules were reduced while the majority, 89.5 ± 2.08%, were oxidized. These data indicate that a 12 h-dexamethasone treatment caused an oxidation of the redox environment.

Hydrogen peroxide resistant WEHI7.2 variants are resistant to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis

Previously, we developed WEHI7.2 variants that overexpress catalase or are selected for resistance to 200 μM H2O2 [13,26]. The catalase activity values are shown in Table 1. The CAT2 catalase clone has a 2-fold increase in catalase activity compared to the vector only transfectants (Neo3) [13]. Twelve hours after adding new medium, CAT38 cells had twice the catalase activity seen in the Neo3 cells; however, the activity declines to 1.4-fold the Neo3 values by 24 h. The H2O2 resistant cells (200R) have a 1.4-fold increase in catalase activity over that in the parental cells [26]. Dexamethasone treatment did not affect the catalase activity in any of the cell variants (data not shown). The CAT38 and 200R cells show delayed loss of cells from the culture in response to dexamethasone compared to that in the WEHI7.2 and Neo3 cells [13,26]. In the CAT2 cells, the cell number did not decrease out through 48 h in dexamethasone [13]. Although these data are consistent with H2O2 playing a key role in glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis, this has not been directly tested.

Table 1.

Catalase activity in exponentially growing WEHI7.2 variants.

| Cell Variant | Catalase activity (μmol H2O2/min/mg prot) | |

|---|---|---|

| 12h | 24ha | |

| WEHI7.2 | 15.2 ± 0.7 | 14.6 ± 0.3 |

| Neo3 | 12.9 ± 0.5 | 13.6 ± 1.5 |

| CAT2 | 25.9 ± 2.0* | 27.2 ± 0.7* |

| CAT38 | 24.4 ± 1.9* | 19.3 ± 0.2* |

| 200R | 18.1 ± 0.6* | 19.9 ± 0.2* |

Values are mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3–7).

denotes significantly different from control values (p ≤ 0.05).

24h values from refs.{Tome, Briehl, 2001; Tome, Baker, 2001}.

The catalase-overexpressing clones and the 200R cells provide excellent tools to directly test the necessity of increased H2O2 for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis signaling. To use the WEHI7.2 variants to determine the role of H2O2 in glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis, we first needed to establish the sequence of apoptotic events in these cells. As shown in Figure 3A, there was a delay in the increase in annexin V positive cells in both the CAT38 and 200R cells compared to the WEHI7.2 and Neo3 cells. Annexin V positive cells increase significantly in 200R cultures and in CAT38 cultures 28 h and 40 h after the addition of dexamethasone, respectively (p≤ 0.05). The CAT2 cells did not show an increase in annexin V positive cells (p≤ 0.05) after 40 h in the presence of dexamethasone. Hb12 cells, which overexpress Bcl-2, also did not show an increase in annexin V positive cells after 40 h of continuous dexamethasone treatment. The Hb12 cells served as a positive control for protection from dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in these experiments.

Figure 3.

Timecourse of apoptosis and caspase 3 activation after dexamethasone treatment in the WEHI7.2 cells and the oxidative stress resistant variants. A. Percentage of apoptotic cells in cultures treated with dexamethasone at t = 0. Symbols are as follows: WEHI7.2 (○); Neo3 (□); 200R (◆); CAT38 (■); CAT2 (▲); Hb12 (●). Cells that were annexin V positive and propidium iodide negative were considered apoptotic. Values have been corrected for annexin V positive cells in vehicle-treated cultures. Values are the mean ± S.E.M (n = 3). This is a representative experiment which has been replicated. In some cases, the error bars are contained within the symbols. The timecourse of the appearance of annexin V positive WEHI7.2, CAT38 and Hb12 cells has been published previously [69]. B. Caspase 3 activity in the cells treated with dexamethasone at t = 0. Values have been corrected for the caspase-3 activity in the control cells. Values are the mean ± S.E.M (n = 3).

Caspase 3 activity due to dexamethasone showed a pattern similar to the increase in annexin V binding (Figure 3B). WEHI7.2 and Neo3 cells showed significantly increased caspase 3 activity due to dexamethasone treatment by 24 h after dexamethasone addition. 200R cells had significantly increased caspase 3 activity after 36 h in dexamethasone. By 36 h post dexamethasone addition, caspase 3 activity was slightly elevated in CAT38 cells. These data suggest that the CAT38 and 200R cells show delayed apoptosis in response to glucocorticoids. CAT2 and Hb12 cells did not show increased caspase 3 activity throughout this timecourse. The sequence of apoptotic events in the oxidative stress resistant cells indicates that the cells are protected from apoptosis proportional to their catalase activity. The two-fold increase in catalase activity in the CAT2 cells provided similar protection to the increased Bcl-2 in the Hb12 cells.

Hydrogen peroxide generation is similar in the WEHI7.2 cells and the variants

To assess the magnitude of the H2O2 signal in the variants in response to dexamethasone, we measured H2O2 metabolism (both generation and removal) in the variants after dexamethasone treatment. The first step was to measure the relative amount of H2O2 generated in the variants and WEHI7.2 cells after dexamethasone treatment. For this purpose, we measured the [H2O2]ss 12 h after dexamethasone addition. During the [H2O2]ss measurements, aminotriazole irreversibly inactivates the catalase once catalase binds one molecule of H2O2. Therefore, catalase is not available to catalytically remove H2O2, its usual function. Under these conditions, the increased catalase in the variants will contribute minimally to increased removal. Thus, the [H2O2]ss reflects what the cells would experience in the absence of catalase and indicates the relative amount of H2O2 generated in response to dexamethasone in the variants.

In all the cells, the [H2O2]ss in the presence of dexamethasone was significantly higher than in the absence of dexamethasone (Table 2). The [H2O2]ss in the variants after dexamethasone treatment was similar to that in the WEHI7.2 cells. In the absence of dexamethasone, the [H2O2]ss was similar in all the cells. These data suggest that the WEHI7.2 cells and the variants generate a similar amount of H2O2 in response to dexamethasone treatment.

Table 2.

Steady state intracellular hydrogen peroxide concentration after a 12 h treatment with dexamethasone.

| Cell Variant | Control [H2O2]ss (pM) | Dexamethasone [H2O2]ss (pM) |

|---|---|---|

| WEHI7.2 | 20.5 ± 5.5 | 55.5 ± 4.7* |

| Neo3 | 19.6 ± 3.4 | 51.2 ± 8.8* |

| CAT2 | 21.5 ± 3.4 | 54.1 ± 3.7* |

| CAT38 | 20.4 ± 5.6 | 50.0 ± 3.2* |

| 200R | 21.0 ± 1.7 | 51.4 ± 7.8* |

Values are mean ± S.E.M. (n = 7–11).

denotes significantly different from control cells (p ≤ 0.05).

Increased catalase decreases intracellular ROS due to dexamethasone treatment

The WEHI7.2 cells and the variants generate a similar H2O2 signal in response to dexamethasone under conditions where catalase is inactivated. When catalase is active, it contributes to H2O2 removal and will influence the amount of H2O2 the cells experience in response to dexamethasone. The extent to which the different amounts of catalase in the WEHI7.2 cells and the variants can alter the amount of the H2O2 signal is unknown. Therefore, we measured H2O2 and downstream oxidative events due to a 12 h dexamethasone treatment in the WEHI7.2 cells and the variants under conditions where catalase was active. We used multiple methods, each of which measures something slightly different, to assess the relative magnitude of the signal.

We first measured the change in DCF fluorescence 12 h after the addition of dexamethasone (Figure 4A). To directly compare the increase in DCF fluorescence due to dexamethasone, the values have been corrected for dye loading and for DCF fluorescence in the vehicle-treated cells. At the 12 h timepoint, where we saw maximal ROS in the WEHI7.2 cells, the Neo3 cells had an increase in DCF fluorescence due to dexamethasone similar to that in the WEHI7.2 cells. The CAT2 and CAT38 cells showed a slight increase in DCF fluorescence due to dexamethasone treatment; the increase was significantly less than that in the WEHI7.2 and Neo3 cells. The 200R cells had slightly less ROS than the WEHI7.2/Neo3 cells. This suggests that some of the variants have a lower amount of ROS 12 h after the addition of dexamethasone than the WEHI7.2 and Neo3 control cells.

Figure 4.

Increased catalase removes H2O2 produced by dexamethasone treatment. A. DCF fluorescence due to a 12 h treatment with dexamethasone in WEHI7.2 (W) cells and the variants. DCF fluorescence values have been corrected for relative dye uptake and DCF fluorescence in vehicle-treated cells. Values are the mean + S.E.M (n = 3 or 4). * denotes significantly different from WEHI7.2 values (p ≤ 0.05). B. Rate of H2O2 efflux due to a 12 h treatment with dexamethasone in WEHI7.2 (W) cells and the variants measured by Amplex® Red. Efflux rates have been corrected for the efflux rate in vehicle-treated cells. Values are the mean ± S.E.M (n = 3 or 4). # denotes significantly different from vehicle-treated cells. * denotes significantly different from WEHI7.2 values (p ≤ 0.05). C. Measurement of reduced GFP 12 h after the addition of dexamethasone in control and dexamethasone-treated WEHI7.2 cell variants. Panels show merged images of reduced GFP (green) and oxidized GFP (red) of a representative control and dexamethasone (DEX) treated cell for each variant. Values are the mean % GFP reduced ± S.E.M. for each treatment in each variant (n = 20–35). * denotes significantly different from control cell values (p ≤ 0.05). D. Intracellular glutathione after 12 h in the absence or presence of dexamethasone. * denotes significantly different from vehicle-treated cells (p ≤ 0.05). E. Quantitation of oxidized proteins from an OxyBlot of samples from cultures incubated for 12 h in the absence or presence of dexamethasone. Values have been corrected for background and actin as a loading control. (n=3).

We next measured whether the cells had increased intracellular H2O2 due to dexamethasone or whether catalase was able to remove it. For this purpose, we used Amplex® Red. This compound remains outside the cell and fluoresces after it is oxidized specifically by H2O2 [35]. H2O2 freely diffuses across the cell membrane, so the extracellular measurement of H2O2 is a good indication of the relative concentration of the intracellular H2O2 [35]. In the absence of dexamethasone, the H2O2 efflux in all the cells was similar (data not shown). However, as shown in Figure 4B, a plot of the difference between dexamethasone- and vehicle-treated cells showed that the WEHI7.2, Neo3 and 200R cells had significantly increased H2O2 efflux in the dexamethasone-treated samples. Addition of catalase to the WEHI7.2 cell medium reduced the dexamethasone-induced Amplex Red® signal to 0.08 ± 1.43 a.u./min/mg prot. confirming that the increase in Amplex Red® signal was due to increased H2O2. There was no difference in H2O2 efflux between the control and dexamethasone-treated cells for the CAT2 and CAT38 cells. The WEHI7.2 and Neo3 cells had the greatest difference in H2O2 efflux between the control and dexamethasone-treated samples. H2O2 efflux was intermediate in the 200R cells; it was significantly less than in the WEHI7.2 cells, but greater than in the CAT2, and CAT38 cells. These data indicate that: 1) there is not enough catalase in the WEHI7.2/Neo3 cells to remove all the H2O2 generated by dexamethasone treatment; and 2) the increased catalase in the CAT2, CAT38 and 200R cells completely or partially removes the excess H2O2.

Removal of H2O2 prevents oxidation of the glutathione pool

We next measured the redox environment in the variants using roGFP2 and the status of the GSSG/2GSH redox couple after a 12 h-dexamethasone treatment. As shown by the roGFP2 data in Figure 4C, the redox environment became more oxidized in the Neo3 cells after dexamethasone treatment. This is similar to the response of the WEHI7.2 cells seen in Figure 2. The redox environment did not change in response to dexamethasone in the CAT2, CAT38 and 200R cells. We found that GSH was decreased 12 h after the addition of dexamethasone in the WEHI7.2 and Neo3 cells (Figure 4D); no change was seen in the CAT2, CAT38 and 200R cells. GSSG was similar in the presence and absence of dexamethasone (Table 3). To assess the redox status of the GSSG/2GSH redox couple we calculated the redox potential (Eh) (Table 3). By this measure, both the WEHI7.2 and Neo3 cells became more oxidized after dexamethasone treatment; CAT2, CAT38 and 200R cells did not. The data indicate that the oxidative stress resistant variants are removing enough of the H2O2 generated by dexamethasone treatment such that there is no change in the redox environment and diminished or no ROS signaling due to dexamethasone.

Table 3.

Glutathione disulfide (GSSG) and the GSSG/2GSH redox potential (Eh) after a 12 h treatment with dexamethasone.

| Cell Variant | GSSG (nmol/mg prot) | Eh (mV) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Dexamethasone | Control | Dexamethasone | |

| WEHI7.2 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | −254.5 ± 0.9 | −241.7 ± 1.0* |

| Neo3 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | −250.2 ± 0.5 | −236.8 ± 2.7* |

| CAT2 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | −248.9 ± 1.0 | −249.9 ± 1.3 |

| CAT38 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | −252.0 ± 0.6 | −250.6 ± 1.4 |

| 200R | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | −254.0 ± 0.8 | −250.4 ± 0.8 |

denotes significantly different from control values (p ≤ 0.05).

Values are the mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Dexamethasone treatment does not cause generalized protein oxidation

To determine whether the increased H2O2, due to dexamethasone treatment, resulted in increased oxidation of proteins we measured overall protein oxidation using an Oxyblot (Figure 4E). We saw no change in the overall oxidation of proteins. This indicates the signal is not at the level of protein oxidative damage signaling; however, we cannot rule out signaling by oxidation of specific individual proteins with this measurement.

Removal of hydrogen peroxide provides protection from a 12 h dexamethasone treatment

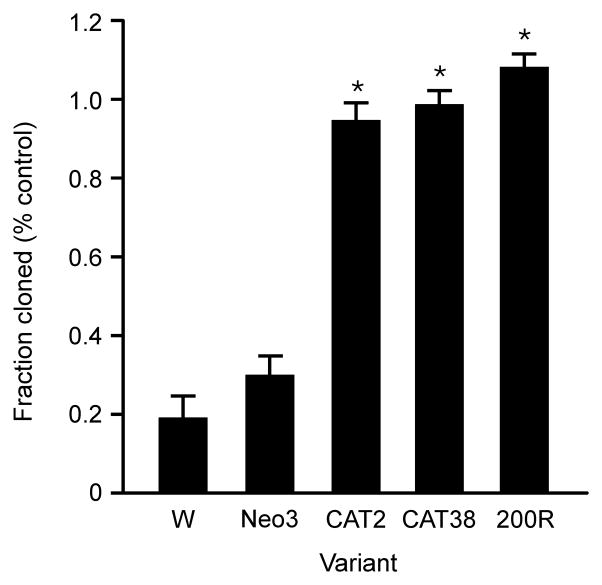

The above data indicate that the oxidative stress resistant variants remove the H2O2 generated by dexamethasone treatment. However, whether removal of the H2O2 is sufficient to ensure cell survival is unknown. To test whether the H2O2 is a key signal in glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in the WEHI7.2 cells, we measured the colony forming ability of the WEHI7.2 cells and the variants after a 12 h dexamethasone treatment. In WEHI7.2 cells, a 12 h dexamethasone treatment was long enough to cause an increase in H2O2, but well short of the 24 h treatment needed to release cytochrome c. In the absence of drug, colony formation in the WEHI7.2 cells and the variants was similar (data not shown). In contrast, if the cells were first treated for 12 h with dexamethasone and then colony formation assessed under drug free conditions, only 20–30% of the WEHI7.2 and Neo3 cells were able to form colonies (Figure 5). For the CAT38, CAT2 and 200R cells, the dexamethasone-treated cells formed the same number of colonies as the vehicle-treated cells. These data suggest that removal of H2O2 is necessary and sufficient to prevent dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in lymphoma cells.

Figure 5.

Removal of H2O2 protects from a 12 h glucocorticoid treatment. Fraction of the 12 h dexamethasone-treated cells that formed colonies for the WEHI7.2 (W) and variant cells. Plotted values are relative to colonies formed by vehicle-treated control cells for each variant. Values are the mean + S.E.M. (n = 3). * denotes significantly different from WEHI7.2 values (p ≤ 0.05).

PEG-catalase addition protects WEHI7.2 and human leukemia cells from dexamethasone

If H2O2 is a necessary signal for dexamethasone-induced apoptosis, one prediction is that addition of PEG-catalase should protect WEHI7.2 and other lymphoid cells from glucocorticoids. To test this prediction, we treated WEHI7.2 cells with 100 U/ml PEG-CAT. PEG-catalase treatment did not increase cellular catalase activity (data not shown). We first measured the effect of PEG-CAT treatment on viable cell number, a combination of cell growth and death (Figure 6A). PEG-CAT alone had no effect, but PEG-CAT partially prevented the decrease due to dexamethasone. When we measured apoptosis (Figure 6A), we saw a decrease in apoptosis due to dexamethasone in the presence of PEG-CAT. The fraction of cells able to form colonies after a 12 h dexamethasone treatment was also significantly increased from ~35% to ~ 65% in the presence of PEG-CAT. These data confirm that removal of H2O2 is protective in the WEHI7.2 cells.

Figure 6.

PEG-CAT treatment protects WEHI7.2 and human leukemia cells from dexamethasone. A. Top panel: Relative number of viable WEHI7.2 cells and middle panel: percent apoptotic WEHI7.2 cells after a 24 h treatment with 1 μM dexamethasone in the presence or absence of 100 U/ml PEG-CAT. Bottom panel: fraction of the 12 h dexamethasone-treated WEHI 7.2 cells that formed colonies. Values are normalized to colonies formed by vehicle-treated cells. B. H2O2 efflux after a 24h dexamethasone treatment using the EC50 for Molt-4 and Jurkat cells, 925 μM and 625 μM, respectively. C. Top panel: Relative number of viable Molt-4 and Jurkat cells after a 48 h treatment with the respective EC50 dexamethasone concentrations in the presence or absence of 100 U/ml PEG-CAT. Bottom panel: Relative percent apoptotic cells after a 36 h treatment with the respective EC50 dexamethasone concentrations. Values are the mean ± SEM (n = 3). * denotes DEX-treated cells are significantly different from vehicle-treated cells. ** denotes DEX/PEG-CAT-treated cells are significantly different from DEX-treated and vehicle-treated cells.

To determine whether our findings in the WEHI7.2 cells extend to human lymphoid tumor cells, we did similar experiments in Molt-4 and Jurkat cells, two human T-cell leukemia cell lines. As shown in Figure 6B, treatment of both Molt-4 and Jurkat cells with dexamethasone resulted in increased H2O2 efflux. Addition of 100 U/ml PEG-CAT to the medium partially prevented the decrease in viable cells and reduced the percentage of apoptotic cells due to dexamethasone treatment (Fig. 6C). The pattern in the human cell lines was similar to that in the WEHI7.2 cells suggesting that the WEHI7.2 cells are an appropriate model for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in human cells.

pERK signaling is preserved in the oxidative stress resistant variants

The data suggest that H2O2 is a required signal for dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. An ability to remove the H2O2 results in resistance to glucocorticoids. The catalase-overexpressing and H2O2-resistant cells model the ROS response that could occur at the site of chronic inflammation. A strategy to circumvent this resistance has potential clinical application for lymphomas that occur at these sites. Our hypothesis is that the ability to remove H2O2 results in the maintenance of survival signaling in the 200R, CAT2 and CAT38 cells after dexamethasone treatment while the dexamethasone sensitive cells will lose the survival signal in response to dexamethasone treatment.

We measured the activity of two survival pathways, NF-κB and pERK, that when activated, can inhibit glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis [6,36,37]. When we compared the effect of dexamethasone on NF-κB transactivation in the sensitive and resistant cells we saw no difference; dexamethasone caused a similar inhibition of NF-κB in all the cells (data not shown). However, as shown in Figure 6A and B, a 12 h dexamethasone treatment decreased pERK2 in both WEHI7.2 and Neo3 cells. In the CAT2, CAT38 and 200R cells dexamethasone treatment did not significantly decrease pERK2. In the WEHI7.2 cells and variants, there is much less ERK1 than ERK2, so we were unable to reliably quantitate phosphorylation of ERK1; qualitatively, the pattern appeared similar to that of ERK2. These data suggest that the ability to remove H2O2 generated by glucocorticoid treatment results in maintenance of pERK survival signaling.

MEK inhibitor treatment sensitizes the oxidative stress resistant cells to dexamethasone

To determine whether it was possible to sensitize the oxidative stress resistant variants to dexamethasone by interrupting pERK2 signaling, we treated the cells with a combination of the MEK inhibitor, PD98059, and dexamethasone. As shown in Figure 7, treatment of the resistant cells with the 50 μM PD98059 was sufficient to decrease the pERK2 signal. We then determined whether the decrease in pERK2 in the presence of dexamethasone caused an increase in measures of apoptosis. In the 200R cells, at 24 h, we saw an increase in caspase 3 activity and annexin V binding in the combined treatment over that in dexamethasone alone. The MEK inhibitor alone did not have an effect. The values for caspase 3 and annexin V binding for the 200R cells in the combined treatment were similar to those in the WEHI7.2 cells at 24 h treated with dexamethasone alone (Figure 3). In the CAT2 and CAT38 cells we saw an increase in both apoptotic measures at 36 h. Although the MEK inhibitor alone in the CAT2 cells did increase the annexin V binding significantly over the control cells, this was not reflected in an increase in caspase 3 activity. The MEK inhibitor alone had no effect on the CAT38 cells. These data suggest that the pERK2 signaling contributes to the dexamethasone resistance of the oxidative stress resistant cells; interruption of this signal sensitizes the cells, at least partially, to dexamethasone.

Figure 7.

Maintenance of pERK signaling contributes to the glucocorticoid resistance of the oxidative stress resistant variants. A. Representative immunoblots showing the phosphorylation status of the MAP kinases after 12 h in the absence (C) or presence (D) of dexamethasone. These blots have been replicated a minimum of 3 times. B. Quantitation of the pERK2 signal showing the relative change in pERK due to dexamethasone treatment. * denotes significantly different from 0 (p ≤ 0.05). Values are the mean change - S.E.M. (n = 3). C. Representative immunoblots showing the phosphorylation status of ERK2 after a 12 h treatment with the MEK inhibitor, PD98059, dexamethasone or the combination of PD98059 plus dexamethasone. These blots have been replicated. Caspase 3 activity and annexin V positive cells after a 24 h (200R) or 36 h (CAT2; CAT38) incubation in the absence or presence of dexamethasone, PD98059 or a combination of both drugs. Values are the mean + S.E.M. (n=3 or 4). * denotes significantly different from vehicle-treated cells (p ≤ 0.05). ** denotes significantly different from dexamethasone only-treated cells (p ≤ 0.05).

Discussion

The data from the current study indicate that H2O2, specifically, is a required signal for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of lymphoma cells. Treatment with dexamethasone increases H2O2 during the signaling phase of apoptosis in the WEHI7.2 cells and the variants. In the control cells (WEHI7.2, Neo3), an inability to remove the excess H2O2 results in decreased GSH, an oxidized redox environment and apoptosis. Cells with an increase in catalase (CAT2, CAT38) or selected for resistance to 200 μM H2O2 (200R) remove enough of the H2O2 signal to prevent apoptosis. These cell variants do not show the decrease in GSH and oxidation of the intracellular environment that occurs in the control cells (WEHI7.2, Neo3). In the CAT2, CAT38 and 200R cells, the ability to remove the H2O2 results in the complete protection from a 12 h dexamethasone treatment as indicated by the ability of the dexamethasone-treated cells to grow colonies at a rate similar to the vehicle-treated cells. We confirmed that H2O2 removal is protective by using PEG-CAT to increase clonogenic survival in dexamethasone-treated WEHI7.2 cells and decrease apoptosis in Molt-4 and Jurkat human leukemia cells. Survival of the cells that remove the H2O2 indicates that H2O2 is a required signal for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis.

The inability of 70% of the WEHI7.2 cells to form colonies after a 12 h dexamethasone treatment suggests that the cells are committed to apoptosis by this timepoint. Cytochrome c is detectable in the cytosol 24 h after the addition of dexamethasone [13]. This is usually considered the commitment step. In this study, we cannot rule out residual glucocorticoid signaling after a 12 h treatment because the dexamethasone may not be completely removed by washing the cells. However, the data suggest the possibility that the WEHI7.2 cells have an irreversible change due to elevated H2O2 that commits them to apoptosis well before cytochrome c release can be detected. The partial removal of the H2O2 in the 200R cells was protective for a 12 h dexamethasone exposure suggesting that a threshold dose of H2O2 must be reached before apoptosis occurs. The partial protection by PEG-CAT treatment supports the concept of a threshold dose requirement. Although in other cells PEG-CAT treatment increased intracellular catalase [38], in the lymphoid cells studied here it did not. The diffusion-mediated removal of H2O2 by extracellular catalase is not expected to be as efficient at H2O2 removal as increased intracellular catalase. Thus, we would expect that the threshold dose would be reached more quickly with PEG-CAT treatment than in the 200R, CAT38 and CAT2 cells and that PEG-CAT would be less protective, as we saw here.

Our data indicate that the amount of H2O2 produced in response to dexamethasone is a necessary signal for dexamethasone induced apoptosis; however, it is unlikely to be sufficient. Calculations of the amount of H2O2 necessary to cause apoptosis in multiple cell types indicates that amounts above 700 nM are required [39,40]. In the WEHI7.2 cells, an extracellular concentration of 25 nM H2O2 is required to achieve the same degree of apoptosis with a similar timing for the appearance of apoptotic events as we measure after treatment with dexamethasone (manuscript submitted). Although membrane lipid and protein composition can influence H2O2 transfer properties [41], the measurements by Antunes and Cadenas indicate that the intracellular concentration of H2O2 will be 7–10 fold lower than the extracellular concentration [42]. Based on these measurements, a 2.5 nM intracellular concentration of H2O2 should be required to induce apoptosis equivalent to a 1 μM dexamethasone treatment. Our measured 55.5 pM [H2O2]ss due to dexamethasone is well below either of these two estimates. Other studies have identified molecular events necessary, but not sufficient, for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. These include induction of Bim [3,37,43] and increased neutral sphingomyelinase (nSMase) [4]. Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis is a complex process that requires the interaction of multiple signals at the molecular level; our study indicates that an increase in H2O2 is one of them.

The magnitude of the [H2O2]ss increase, from 20 to 55 pM, and the timing, prior to the appearance of other apoptotic indicators, suggests that H2O2 is acting as a signal. The increase in H2O2 is not enough to cause widespread protein oxidation and damage. Further, the increased H2O2 did not block glucocorticoid receptor function nor downstream caspase activity, both of which can be inactivated by oxidation [44,45]. This is consistent with the magnitude of the H2O2 increase being insufficient to induce apoptosis as a sole agent. There is increasing evidence that H2O2 can act locally and selectively to alter molecular events. H2O2 produced enzymatically can regulate receptor activation [46,47]. It can also alter transcription events without changes in GSH [48–50]. Other studies have reported H2O2 signals contribute to apoptosis due to glucose deprivation [28] or signaling events during hyperglycemia [51]. In the above studies where the amount of H2O2 has been quantitated [28,50,51], it is in the same range as that seen after dexamethasone treatment in the WEHI7.2 cells.

The increase in H2O2 drives oxidation of the GSSG/2GSH redox couple. In the WEHI7.2 and Neo3 cells there is an increase in H2O2 and oxidation of the GSSG/2GSH redox couple. In the CAT2 and CAT38 cells where the cells remove all the excess H2O2 the GSSG/2GSH redox couple is unchanged. The 200R cells show the sequence well; 12 h after the addition of dexamethasone there is an increase in H2O2, but not a significant change in the GSSG/2GSH redox couple. These data show that for dexamethasone the ROS are the critical signal and do not play a “bystander” [20] role. This is in contrast to the agents tested by Franco et al. that induce apoptosis via the intrinsic pathway where the change in GSH is the initial event [20]. Our data suggest that there is an agent-specific role of ROS in apoptosis signaling upstream of the GSH alterations at least for dexamethasone.

Oxidation of the GSSG/2GSH redox couple may be required for apoptosis. Many studies suggest that this is the critical event [20,52]. Our data support this concept. The WEHI7.2 and Neo3 cells, where there is an increase in H2O2 and oxidation of the GSSG/2GSH redox couple have a loss of clonogenicity. The 200R cells with the increase in H2O2, but no change in the GSSG/2GSH redox couple show no decrease in clonogenicity. A change in the GSSG/2GSH Eh is sufficient to alter transcriptional profiles [53]. This would also serve to amplify the H2O2 signal. H2O2, as a signaling molecule, needs to have a local target or sensor to be effective. A change in the GSSG/2GSH Eh is a more global effect within a cell. This change could cause an effect further from the source of H2O2 production to propagate the signal. Alterations in GSH, independent of ROS generation, can cause apoptosis [20,52,54].

There are also proteins, known to participate in glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis, that are potential targets of a local H2O2 increase. One possible target is neutral sphingomyelinase (nSMase). Activation of nSMase is required for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis [4]. nSMase2 is activated by H2O2 treatment [55]. Elevated H2O2 may also participate in cytochrome c release. Movement of cytochrome c into the cytosol is thought to occur via a two-step process. Cytochrome c is first released from the outer surface of the inner mitochondrial membrane into the intermembrane space. Excess H2O2 will cause cytochrome c to act as a peroxidase [56,57]. This results in the oxidation of cardiolipin in the inner mitochondrial membrane and release of cytochrome c into the intermembrane space [56,57]. Cytochrome c can now move into the cytosol once mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization occurs [58]. The critical target(s) or sensors of H2O2 during glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis signaling remain to be elucidated.

The catalase overexpressing cells are resistant to glucocorticoids proportional to their ability to remove the H2O2 signal. These cells are able to maintain pERK survival signaling in response to dexamethasone treatment while the sensitive cells are not. pERK signaling is a major survival pathway in T-cells that signals from the T-cell receptor through Ras-MEK-ERK [6]. Activation of this pathway inhibits glucocorticoid-induced T-cell apoptosis [6,59]. Treatment of other lymphoid cells with glucocorticoids results in a decrease of pERK signaling in some cells, but not in others, e.g. [60,61]. Some of the inconsistency may be due to the timepoint chosen for the measurements; we observed a significant rebound (data not shown), thus the timepoint had to be chosen carefully to observe the decrease. Cell-type specificity also plays a role [62]. The ability of a MEK inhibitor to sensitize lymphoid/myeloid cells to glucocorticoids, as we see in the current study, is nearly universal [6,43,60,61,63].

We do not know how an increase in H2O2 results in loss of pERK signaling. In other studies, a small increase in H2O2 usually causes an increase in pERK, e.g. [49,64,65]. The decrease in pERK seen in the WEHI7.2 cells is likely the result of indirect signaling by H2O2 or a change in the GSSG/2GSH Eh which results in the inhibition of the survival pathway. This fits our observation that the magnitude of the H2O2 increase is insufficient to cause apoptosis as a single agent. For the WEHI7.2 cells, loss of pERK could be via an inhibition of MEK or an increase in the activity of the dual-specificity phosphatases (DUSPs). DUSPs are a family of phosphatases that dephosphorylate MAPKs in a molecule and cell compartment specific manner [66]. In other cell types glucocorticoids increase the DUSP MKP-1 [67,68]. The details of the signaling pathway remain to be elucidated.

The complete protection from glucocorticoids seen in the cells that are able to remove the H2O2 has implications for lymphoma growth and glucocorticoid chemotherapy response. Lymphomas often arise at sites of chronic inflammation where cells are exposed to increased ROS and cytokines as the host mounts an immune response [21]. Chronic exposure to ROS can result in increased antioxidant defenses, similar to the 200R cells. Tumor cells with increases in catalase or glutathione peroxidase are likely to exhibit glucocorticoid resistance. In our model system, very modest increases in catalase provide complete protection from a 12 h treatment with a glucocorticoid dose that saturates the receptors. Tumor xenografts from CAT38 cells exhibited increased net tumor growth due primarily to decreased apoptosis in the tumor cells [13]. Decreased apoptosis in the tumor cells may be due, in part, to resistance to physiological levels of glucocorticoids. These data suggest that lymphomas that arise under conditions of chronic inflammation could exhibit chemoresistance. Successful treatment of lymphomas at these sites may need to account for alterations in antioxidant defenses that block apoptosis signaling. The ability of MEK inhibitors to overcome the glucocorticoid resistance of the oxidative stress resistant cells suggests a potential clinical strategy for the treatment of these lymphomas.

Highlights.

Glucocorticoids cause apoptosis in lymphoma cells.

Glucocorticoid treatment increases intracellular H2O2.

Removal of the excess H2O2 causes glucocorticoid resistance.

H2O2 is a necessary signal for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis.

MEK inhibitors overcome glucocorticoid resistance in ROS-resistant cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank: Drs. Lisa Rimsza and Terry Landowski for Molt-4 and Jurkat cells; Debbie Sakiestewa and Barb Carolus for flow cytometry assistance; Dr. David Elliot for technical advice and assistance with the DeltaVision Restoration Microscopy System; Dr. Garry Buettner and Brian Wagner for help with the [H2O2]ss measurements; Dr. S. James Remington for the roGFP2 construct; Betty Glinsmann-Gibson for technical advice on cloning methods; and David Stringer and Dr. Eugene Gerner for use of critical equipment. Funding for this study comes from: the National Cancer Institute (CA 71768) (M.M.B); the Arizona Cancer Center Support Grant (CA 023074); and the Department of Pathology. M.C.J. was partially supported by a T-32 traineeship from the N.C.I. (CA 09213).

Abbreviations

- 200R

WEHI7.2 cells selected for resistance to 200 μM H2O2

- 7-AAD

7 aminoactinomycin D

- CAT2, CAT38

WEHI7.2 clones overexpressing rat catalase

- cDCFH

5-(and-6)-carboxy-2′7′dichlorofluorescin

- DCFH/DCF

2′7′dichlorodihydrofluorescin/dichlorofluorescein

- DEX

dexamethasone

- DUSP

dual-specificity phosphatases

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- [H2O2]ss

steady state hydrogen peroxide concentration

- Hb12

WEHI7.2 cells overexpressing human Bcl-2

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MEK

MAPK/ERK kinase

- MOMP

mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization

- PEG-CAT

polyethylene glycol conjugated catalase

- pNA

p-nitroanilide

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- nSMase

neutral sphingomyelinase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Distelhorst CW. Recent insights into the mechanism of glucocorticosteroid-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:6–19. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herold MJ, McPherson KG, Reichardt HM. Glucocorticoids in T cell apoptosis and function. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:60–72. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5390-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Z, Malone MH, He H, McColl KS, Distelhorst CW. Microarray analysis uncovers the induction of the proapoptotic BH3-only protein Bim in multiple models of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23861–23867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301843200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cifone MG, Migliorati G, Parroni R, Marchetti C, Millimaggi D, Santoni A, Riccardi C. Dexamethasone-induced thymocyte apoptosis: apoptotic signal involves the sequential activation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C, acidic sphingomyelinase, and caspases. Blood. 1999;93:2282–2296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Squier MK, Cohen JJ. Calpain, an upstream regulator of thymocyte apoptosis. J Immunol. 1997;158:3690–3697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamieson CA, Yamamoto KR. Crosstalk pathway for inhibition of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis by T cell receptor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7319–7324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rathmell JC, Lindsten T, Zong WX, Cinalli RM, Thompson CB. Deficiency in Bak and Bax perturbs thymic selection and lymphoid homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:932–939. doi: 10.1038/ni834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scorrano L, Korsmeyer SJ. Mechanisms of cytochrome c release by proapoptotic BCL-2 family members. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304:437–444. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00615-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bachmann PS, Gorman R, Mackenzie KL, Lutze-Mann L, Lock RB. Dexamethasone resistance in B-cell precursor childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia occurs downstream of ligand-induced nuclear translocation of the glucocorticoid receptor. Blood. 2005;105:2519–2526. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tonomura N, McLaughlin K, Grimm L, Goldsby RA, Osborne BA. Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of thymocytes: requirement of proteasome-dependent mitochondrial activity. J Immunol. 2003;170:2469–2478. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van de Wetering CI, Coleman MC, Spitz DR, Smith BJ, Knudson CM. Manganese superoxide dismutase gene dosage affects chromosomal instability and tumor onset in a mouse model of T cell lymphoma. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:1677–1686. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tome ME, Baker AF, Powis G, Payne CM, Briehl MM. Catalase-overexpressing thymocytes are resistant to glucocorticoid- induced apoptosis and exhibit increased net tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2766–2773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ricci JE, Munoz-Pinedo C, Fitzgerald P, Bailly-Maitre B, Perkins GA, Yadava N, Scheffler IE, Ellisman MH, Green DR. Disruption of mitochondrial function during apoptosis is mediated by caspase cleavage of the p75 subunit of complex I of the electron transport chain. Cell. 2004;117:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bustamante J, Tovar-B A, Montero G, Boveris A. Early redox changes during rat thymocyte apoptosis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;337:121–128. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.9754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slater AF, Nobel CS, Maellaro E, Bustamante J, Kimland M, Orrenius S. Nitrone spin traps and a nitroxide antioxidant inhibit a common pathway of thymocyte apoptosis. Biochem J. 1995;306:771–778. doi: 10.1042/bj3060771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torres-Roca JF, Lecoeur H, Amatore C, Gougeon M-L. The early intracellular production of a reactive oxygen intermediate mediates apoptosis in dexamethasone-treated thymocytes. Cell Death Differ. 1995;2:309–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hockenbery DM, Oltvai ZN, Yin XM, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 functions in an antioxidant pathway to prevent apoptosis. Cell. 1993;75:241–251. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80066-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang JF, Jerrells TR, Spitzer JJ. Decreased production of reactive oxygen intermediates is an early event during in vitro apoptosis of rat thymocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20:533–542. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franco R, Panayiotidis MI, Cidlowski JA. Glutathione depletion is necessary for apoptosis in lymphoid cells independent of reactive oxygen species formation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30452–30465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703091200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tavani A, La Vecchia C, Franceschi S, Serraino D, Carbone A. Medical history and risk of Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2000;9:59–64. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200002000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spitz DR, Li GC, McCormick ML, Sun Y, Oberley LW. The isolation and partial characterization of stable H2O2-resistant variants of Chinese hamster fibroblasts. Basic Life Sciences. 1988;49:549–552. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5568-7_86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cantoni O, Guidarelli A, Sestili P, Mannello F, Gazzanelli G, Cattabeni F. Development, characterization of hydrogen peroxide-resistant Chinese hamster ovary cell variants--I. Relationship between catalase activity and the induction/stability of the oxidant-resistant phenotype. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;45:2251–2257. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90196-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker A, Payne CM, Briehl MM, Powis G. Thioredoxin, a gene found overexpressed in human cancer, inhibits apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5162–5167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris AW, Bankhurst AD, Mason S, Warner NL. Differentiated functions expressed by cultured mouse lymphoma cells II. Theta antigen, surface immunoglobulin and a receptor for antibody on cells of a thymoma cell line. J Immunol. 1973;110:431–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tome ME, Briehl MM. Thymocytes selected for resistance to hydrogen peroxide show altered antioxidant enzyme profiles and resistance to dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:953–961. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Efferth T, Briehl MM, Tome ME. Role of antioxidant genes for the activity of artesunate against tumor cells. Int J Oncol. 2003;23:1231–1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmad IM, Aykin-Burns N, Sim JE, Walsh SA, Higashikubo R, Buettner GR, Venkataraman S, Mackey MA, Flanagan SW, Oberley LW, Spitz DR. Mitochondrial O2*- and H2O2 mediate glucose deprivation-induced stress in human cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4254–4263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411662200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones DP. Redox potential of GSH/GSSG couple: assay and biological significance. Methods Enzymol. 2002;348:93–112. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)48630-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanson GT, Aggeler R, Oglesbee D, Cannon M, Capaldi RA, Tsien RY, Remington SJ. Investigating mitochondrial redox potential with redox-sensitive green fluorescent protein indicators. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13044–13053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Royall JA, Gwin PD, Parks DA, Freeman BA. Responses of vascular endothelial oxidant metabolism to lipopolysaccharide and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;294:686–694. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90742-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myers JL, Well AD. Research Design and Statistical Analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zielonka J, Kalyanaraman B. “ROS-generating mitochondrial DNA mutations can regulate tumor cell metastasis”-a critical commentary. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:1217–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer AJ, Brach T, Marty L, Kreye S, Rouhier N, Jacquot JP, Hell R. Redox-sensitive GFP in Arabidopsis thaliana is a quantitative biosensor for the redox potential of the cellular glutathione redox buffer. Plant J. 2007;52:973–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner BA, Evig CB, Reszka KJ, Buettner GR, Burns CP. Doxorubicin increases intracellular hydrogen peroxide in PC3 prostate cancer cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;440:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosono N, Kishi S, Iho S, Urasaki Y, Yoshida A, Kurooka H, Yokota Y, Ueda T. Glutathione S-transferase M1 inhibits dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in association with the suppression of Bim through dual mechanisms in a lymphoblastic leukemia cell line. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:767–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma S, Lichtenstein A. Dexamethasone-induced apoptotic mechanisms in myeloma cells investigated by analysis of mutant glucocorticoid receptors. Blood. 2008;112:1338–1345. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-124156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beckman JS, Minor RL, Jr, White CW, Repine JE, Rosen GM, Freeman BA. Superoxide dismutase and catalase conjugated to polyethylene glycol increases endothelial enzyme activity and oxidant resistance. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:6884–6892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stone JR, Yang S. Hydrogen peroxide: a signaling messenger. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:243–270. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antunes F, Cadenas E. Cellular titration of apoptosis with steady state concentrations of H(2)O(2): submicromolar levels of H(2)O(2) induce apoptosis through Fenton chemistry independent of the cellular thiol state. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:1008–1018. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00493-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bienert GP, Schjoerring JK, Jahn TP. Membrane transport of hydrogen peroxide. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:994–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Antunes F, Cadenas E. Estimation of H2O2 gradients across biomembranes. FEBS Lett. 2000;475:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01638-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu J, Quearry B, Harada H. p38-MAP kinase activation followed by BIM induction is essential for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in lymphoblastic leukemia cells. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:3539–3544. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borutaite V, Brown GC. Caspases are reversibly inactivated by hydrogen peroxide. FEBS Lett. 2001;500:114–118. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02593-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Makino Y, Yoshikawa N, Okamoto K, Hirota K, Yodoi J, Makino I, Tanaka H. Direct association with thioredoxin allows redox regulation of glucocorticoid receptor function. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3182–3188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woo HA, Yim SH, Shin DH, Kang D, Yu DY, Rhee SG. Inactivation of peroxiredoxin I by phosphorylation allows localized H(2)O(2) accumulation for cell signaling. Cell. 2010;140:517–528. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mishina NM, Tyurin-Kuzmin PA, Markvicheva KN, Vorotnikov AV, Tkachuk VA, Laketa V, Schultz C, Lukyanov S, Belousov VV. Does cellular hydrogen peroxide diffuse or act locally? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:1–7. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Go YM, Gipp JJ, Mulcahy RT, Jones DP. H2O2-dependent activation of GCLC-ARE4 reporter occurs by mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways without oxidation of cellular glutathione or thioredoxin-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5837–5845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nelson KK, Subbaram S, Connor KM, Dasgupta J, Ha XF, Meng TC, Tonks NK, Melendez JA. Redox-dependent matrix metalloproteinase-1 expression is regulated by JNK through Ets and AP-1 promoter motifs. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:14100–14110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601820200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dasgupta J, Kar S, Liu R, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B, Remington SJ, Chen C, Melendez JA. Reactive oxygen species control senescence-associated matrix metalloproteinase-1 through c-Jun-N-terminal kinase. J Cell Physiol. 2010;225:52–62. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quijano C, Castro L, Peluffo G, Valez V, Radi R. Enhanced mitochondrial superoxide in hyperglycemic endothelial cells: direct measurements and formation of hydrogen peroxide and peroxynitrite. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3404–H3414. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00761.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Circu ML, Aw TY. Reactive oxygen species, cellular redox systems, and apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kirlin WG, Cai J, Thompson SA, Diaz D, Kavanagh TJ, Jones DP. Glutathione redox potential in response to differentiation and enzyme inducers. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:1208–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pias EK, Aw TY. Apoptosis in mitotic competent undifferentiated cells is induced by cellular redox imbalance independent of reactive oxygen species production. FASEB J. 2002;16:781–790. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0784com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levy M, Castillo SS, Goldkorn T. nSMase2 activation and trafficking are modulated by oxidative stress to induce apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:900–905. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldsteins G, Keksa-Goldsteine V, Ahtoniemi T, Jaronen M, Arens E, Akerman K, Chan PH, Koistinaho J. Deleterious role of superoxide dismutase in the mitochondrial intermembrane space. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8446–8452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706111200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kagan VE, Tyurin VA, Jiang J, Tyurina YY, Ritov VB, Amoscato AA, Osipov AN, Belikova NA, Kapralov AA, Kini V, Vlasova II, Zhao Q, Zou M, Di P, Svistunenko DA, Kurnikov IV, Borisenko GG. Cytochrome c acts as a cardiolipin oxygenase required for release of proapoptotic factors. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:223–232. doi: 10.1038/nchembio727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ott M, Robertson JD, Gogvadze V, Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S. Cytochrome c release from mitochondria proceeds by a two-step process. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1259–1263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241655498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ko M, Jang J, Ahn J, Lee K, Chung H, Jeon SH, Seong RH. T cell receptor signaling inhibits glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis by repressing the SRG3 expression via Ras activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21903–21915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402144200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rambal AA, Panaguiton ZL, Kramer L, Grant S, Harada H. MEK inhibitors potentiate dexamethasone lethality in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells through the pro-apoptotic molecule BIM. Leukemia. 2009;23:1744–1754. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Garza AS, Miller AL, Johnson BH, Thompson EB. Converting cell lines representing hematological malignancies from glucocorticoid-resistant to glucocorticoid-sensitive: signaling pathway interactions. Leuk Res. 2009;33:717–727. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ryter SW, Kim HP, Hoetzel A, Park JW, Nakahira K, Wang X, Choi AM. Mechanisms of cell death in oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:49–89. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.9.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tanaka T, Okabe T, Gondo S, Fukuda M, Yamamoto M, Umemura T, Tani K, Nomura M, Goto K, Yanase T, Nawata H. Modification of glucocorticoid sensitivity by MAP kinase signaling pathways in glucocorticoid-induced T-cell apoptosis. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:1542–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Preston TJ, Muller WJ, Singh G. Scavenging of extracellular H2O2 by catalase inhibits the proliferation of HER-2/Neu-transformed rat-1 fibroblasts through the induction of a stress response. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9558–9564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004617200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baty JW, Hampton MB, Winterbourn CC. Proteomic detection of hydrogen peroxide-sensitive thiol proteins in Jurkat cells. Biochem J. 2005;389:785–795. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]