Abstract

Percutaneous heart valves are revolutionizing valve replacement surgery by offering a less invasive treatment option for high-risk patient populations who have previously been denied the traditional open chest procedure. Percutaneous valves need to be crimped to accommodate a small-diameter catheter during deployment, and they must then open to the size of heart valve. Thus the material used must be strong and possess elastic recoil for this application. Most percutaneous valves utilize bovine pericardium as a material of choice. One possible method to reduce the device delivery diameter is to utilize a thin, highly elastic tissue. Here we investigated porcine vena cava as an alternative to bovine pericardium for percutaneous valve application. We compared the structural, mechanical, and in vivo properties of porcine vena cava to those of bovine pericardium. While the extracellular matrix fibers of pericardium are randomly oriented, the vena cava contains highly aligned collagen and elastin fibers that impart strength to the vessel in the circumferential direction and elasticity in the longitudinal direction. Moreover, the vena cava contains a greater proportion of elastin, whereas the pericardium matrix is mainly composed of collagen. Due to its high elastin content, the vena cava is significantly less stiff than the pericardium, even after crosslinking with glutaraldehyde. Furthermore, the vena cava’s mechanical compliance is preserved after compression under forces similar to those exerted by a stent, whereas pericardium is significantly stiffened by this process. Bovine pericardium also showed surface cracks observed by scanning electron microscopy after crimping that were not seen in vena cava tissue. Additionally, the vena cava exhibited reduced calcification (46.64 ± 8.15 μg Ca/mg tissue) as compared to the pericardium (86.79 ± 10.34 μg/mg). These results suggest that the vena cava may enhance leaflet flexibility, tissue resilience, and tissue integrity in percutaneous heart valves, ultimately reducing the device profile while improving the durability of these valves.

Keywords: Vena cava, bioprosthetic heart valve, transcatheter heart valve, bioprosthetic tissue, percutaneous valve

Introduction

Each year, over 300,000 heart valve replacement surgeries are performed worldwide [1], and this number is expected to continue growing as life expectancies increase. Although the demand for replacement valves is growing, current clinically available valve substitutes have still not been perfected. Mechanical valves present problems with thrombosis and necessitate lifetime anticoagulation therapy, whereas bioprosthetic valves have limited durability [2]. Furthermore, valve replacement surgery is very invasive, and high risk patient populations are often denied surgery. Over 50% of elderly populations with aortic stenosis are not offered surgery because the mortality risk is too great [3, 4]. To avoid open chest surgery, a new, less invasive option, percutaneous aortic valve replacement (PAVR), has been developed [5, 6]. PAVR involves transcatheter delivery of a crimped, stented valve to the aortic annulus. The valve is deployed using a balloon catheter or through self-expansion. A major limitation of percutaneous heart valves (PHVs) is the diameter to which the stent can be crimped without damaging the heart valve tissue within. The device profile precludes use in small or tortuous vascular systems, limiting the candidate patient pool for PAVR [7]. Two percutaneous heart valves (PHVs), fabricated from glutaraldehyde-fixed bovine pericardial tissue, are currently in clinical trials [6]. Recent clinical studies show that patients with severe aortic stenosis who were not suitable candidates for surgery, PHVs, as compared with standard therapy, significantly reduced the rates of death from any cause [8]. No published data yet exists for the status of pericardium after crimping in the stent. Here we tested the structural, mechanical, and in vivo properties of bovine pericardium after crimping and compared a new elastic material namely porcine vena cava for such an application. Porcine vena cava was chosen due to its enhanced flexibility and resilience, as it has a higher elastin content and greater stiffness and strength than other vascular tissues [9].

Materials and Methods

Materials

Acetyl acetone, p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), sodium chloride, TRIS, ammonium molybdate, L-ascorbic acid, and sodium azide were purchase from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). Ammonium acetate, chondroitinase ABC from Proteus vulgaris, collagenase type VII from Clostridium histolyticum, (D+) glucosamine HCl, hyaluronidase type IV-S from bovine testes, and calcium carbonate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corp (St. Louis, MO). Elastase from porcine pancreas (135 U/mg) was purchased from Elastin Products Company (Owensville, MO). EM Grade Glutaraldehyde- 8% wt. in water was purchased from Polysciences Inc. (Warrington, PA). Ultra II ultra pure hydrochloric acid was purchased from J.T Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ). Sulfuric acid was purchased from EMD Chemicals, Inc. (Darmstadt, Germany). Absolute ethanol was obtained from Pharmco-AAPER (Shelbyville, KY).

Methods

Crosslinking xenograft tissue

Fresh bovine pericardium (BP) and porcine superior vena cava (PVC) were obtained from Animal Technologies, Inc (Tyler, TX). The tissue was packed in saline, kept on ice and shipped overnight. All tissues were rinsed in ice cold saline prior to treatment. The pericardial sacs were cut open along the midline, laid out in a rectangular sheet, and cut into rectangular strips, with the length of the strip corresponding to the circumferential axis of the sac and the width to the base-to-apex axis. These orientations will subsequently be referred to as the circumferential and longitudinal directions, respectively. The vena cava tissues were cut along the longitudinal axis and opened up into flat sheets. Rectangular pieces were cut, with the length of the rectangle corresponding to the longitudinal direction and the width corresponding to the circumferential direction of the vessel. Within three hours of obtaining the tissue, several fresh tissue pieces were directly frozen at −4°C or taken immediately for assays, while the rest were crosslinked using glutaraldehyde. Pericardial or vena cava strips were placed in 0.6% glutaraldehyde in 50 mM HEPES-buffered saline solution at pH 7.4 at room temperature. After 24 hours incubation in 0.6% glutaraldehyde, the solution was replaced by 0.2% glutaraldehyde. Tissues were stored in 0.2% GLUT for at least 6 days before assays were performed. Crosslinked tissues are depicted as GLUT.

Collagenase and Elastase Assays

The tissues’ ability to resist enzymatic degradation of collagen and elastin was assessed for fresh and GLUT pericardium and vena cava. All tissues were rinsed in deionized (DI) water, lyophilized, and weighed (initial dry weight). Then, the tissues were treated with porcine pancreatic elastase or Type VII collagenase. Approximately 2 cm² pieces of tissue were immersed in 1.2 mL of 5.0 U/mL elastase (100mM Tris buffer, 1mM CaCl2, 0.02% NaN3) or 1.2 mL of 150 U/mL collagenase (50 mM CaCl2, 0.02% NaN3, pH 8.0). The elastase-treated groups were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours with constant agitation, while the collagenase-treated groups were incubated under identical conditions for 48 hours. The samples were then rinsed in DI water, lyophilized, and weighed again (final dry weight). The degree of enzymatic degradation of the tissue was quantified as the percent weight loss, which was calculated by dividing the difference in final and initial dry weights by the initial dry weight.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed on fresh and crosslinked tissues to assess the collagen denaturation temperature (Td), which is represented by an endothermic peak in the heating curve [10]. Tissue samples of approximately 7–10 mg were excised, blotted with tissue paper to remove surface water, and placed in hermetically-sealed aluminum pans. Samples were heated from 30°C to 60°C at 5°C per minute, held at 60°C for one minute, and then heated from 60°C to 90°C at 2°C per minute. The resulting heating curves were analyzed using Thermal Analysis software. The collagen denaturation temperature was recorded at the height of the endothermic peak.

Glycosaminoglycan (GAG) Quantification by Hexosamine Analysis

Total hexosamine content in the tissue was used as an estimate of total GAG content, as previously described [11, 12]. The sample tissues were weighed, lyophilized, and hydrolyzed in 2 mL of 6 M HCl for 20 hours at 95 °C. The samples were then dried under nitrogen gas and resuspended in 2 mL of 1 M NaCl. The samples were reacted with 1 mL of 3% acetylacetone in 1.25 M sodium carbonate solution and incubated at 95 °C for 1 hour. The samples were then cooled to room temperature and further reacted with 4 mL of absolute ethanol and 2 mL of Ehrlich’s reagent (0.18 M p-diemethyl-aminobenzaldehyde, 50% ethanol in 3.0 N HCl). The samples were incubated at room temperature for 45 minutes to allow for color development. Then, 300 mL of each sample was pipetted into a 96-well plate, using D (+) glucosamine solutions (1–200μg) as controls. Spectrophotometric analysis was performed at 540 nm. All calculated hexosamine values were normalized to their respective dry tissue weights.

Uniaxial Tensile Testing

Fresh and GLUT tissues were subjected to uniaxial mechanical testing. Small tissue strips (approximately 10 mm in length and 3 mm in width) were excised, the tissue thickness was measured with a caliper, and each sample was placed between the grips of an MTS Synergie 100 (MTS Systems Corporation; Eden Prairie, MN). A 10 N load cell was used to apply a tensile force to the tissue samples, and the tissue was stretched at a constant rate of 12.5 mm/min to obtain stress-strain curve. TestWorks 4 software (MTS Systems Corporation; Eden Prairie, MN) was used to obtain the elastic modulus of the sample, as defined as the slope of the engineering stress-strain curve, at both the low modulus and upper modulus regions of the curve. Uniaxial tensile tests were performed on fresh and GLUT fixed PVC and BP in both the longitudinal (long) and circumferential (circ) directions. These directions refer to the anatomic orientations previously described.

Tissue Resilience to Crimp Force

GLUT samples were subjected to compressive forces to simulate tissue compression within a PHV stent. Tissue resilience was assessed by observing the tissues’ mechanical response and surface condition following compression. The crimp test was performed at St. Jude Medical Inc., St Paul, MN. Rectangular samples of GLUT pericardium and vena cava were folded back on themselves twice (in the longitudinal direction) and compressed under a 35N static load for 30 minutes each. The tissue was then removed and returned to our lab for further analysis.

The crimped tissue was subjected to tensile testing in order to evaluate how crimping affects tissue mechanics. Uniaxial tensile tests, as described above, were performed on crimped GLUT vena cava and pericardium. The results were compared to GLUT control tissue that had not previously been subjected to any forces.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to assess the degree of tissue damage following the crimp test. Samples were prepared for SEM by rinsing in DI water, dehydrating through increasing concentrations of ethanol, and critical point drying. The samples were mounted on the specimen stub with double-sided carbon tape and viewed with the TM3000 (Hitachi; Tokyo, Japan).

Subdermal Implantation

Subdermal implantation of bioprosthetic tissue in small animals is frequently used to assess the in vivo responses, such as calcification and inflammation [2]. Small samples (approximately 2 cm²) of GLUT porcine vena cava and bovine pericardium (n=10) were excised and rinsed in sterile saline (3 × 30 minutes) prior to surgery. All animals received humane care in compliance with protocols that have been approved by the Clemson University Animal Research Committee and NIH. Male juvenile Sprague Dawley rats (35–40 g; Harlan Laboratories; Indianapolis, IN) were anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane gas. Two small incisions (one on each side lateral to the spine) were made on the dorsal side of the rat. A subdermal pocket was made in conjunction with each incision, and one tissue sample was placed in each pocket. The incision was closed via surgical staples. Animals were sacrificed at three weeks using carbon dioxide asphyxiation. The implant and tissue capsule were explanted and prepared for further analysis.

Calcium and phosphorus analysis of explants

Tissue samples were immediately frozen on dry ice following the explant surgery. The samples were lyophilized, weighed, and hydrolyzed in 1 mL of 6N Ultrex II HCl for 20 hours at 95°C. The samples were then dried under nitrogen gas and dissolved in 1 mL of 0.01 N Ultrex HCl. This stock solution was used for both calcium and phosphorus analyses. For calcium analysis the solution was diluted by 1:50 in Atomic Absorption Matrix (0.3N Ultrex HCl + 0.5% lanthanum oxide). The calcium content of each sample was determined by atomic absorption spectroscopy (Perkin-Elmer 3030 Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer; Norwalk, CT). The results were normalized by the dry tissue weight.

For phosphorus quantification, the solution was diluted by 1:100 in DI water for a final volume of 1 mL. To this solution, 1 mL of reagent C (2.5% ammonium molybdate with 6N sulfuric acid and 10% L-ascorbic acid) was added, and the mixture was reacted at 37°C for two hours. The samples were cooled to room temperature, and 250 μl of each was pipetted into a 96-well plate. Spectrophotometric analysis was performed at 820 nm, and the results were normalized to the dry tissue weight. Additionally, the molar ratio of calcium to phosphorus (Ca:P ratio) for each implant was calculated.

Statistical Analysis

Results are represented as a mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed by a two-tailed student’s t-test of unequal variance. Significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Collagen Stability

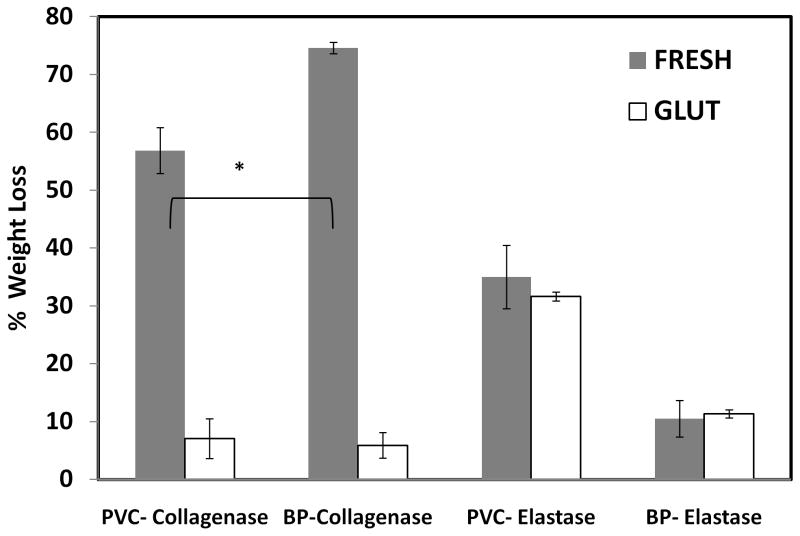

As expected, fresh tissues were degraded after incubation in collagenase (Figure 1). However, fresh pericardium lost significantly more weight than fresh vena cava (74.59% ± 1.008% versus 56.865% ± 3.989%). Glutaraldehyde crosslinking drastically decreased the amount of weight lost from both tissues to less than 10% of dry weight.

Figure 1.

Collagen and elastin stability against enzymes, represented as a percentage of dry tissue weight loss (n= 6, * p<0.05)

Collagen stability was also indirectly assessed by differential scanning calorimetry. The collagen denaturation temperature of hydrated tissues (Td) was determined by analyzing the endothermic peak in the heating curve. Fresh tissues exhibited the lowest denaturation temperatures (62.783 ± 0.183 °C for vena cava and 63.630 ± 0.192 °C for pericardium) while glutaraldehyde crosslinking caused a significant increase in Td to 86.383 ± 0.495 °C and 85.487 ± 0.168 °C respectively. There was no significant difference between Td for vena cava and pericardium suggesting that the collagen component of both tissues was adequately crosslinked.

Elastin Stability

Fresh vena cava incubated in elastase lost 35.656% ± 5.470% of dry weight, revealing that elastin is a major structural component in the vena cava extracellular matrix (Figure 1). Fresh pericardium, in contrast, lost only 10.513% ± 0.710% of dry weight after elastase digestion due to its lower elastin content. GLUT-crosslinking did not protect elastin from degradation in both tissues. However, the amount of weight lost from the vena cava was significantly greater than that of the corresponding pericardium in both the fresh and GLUT groups.

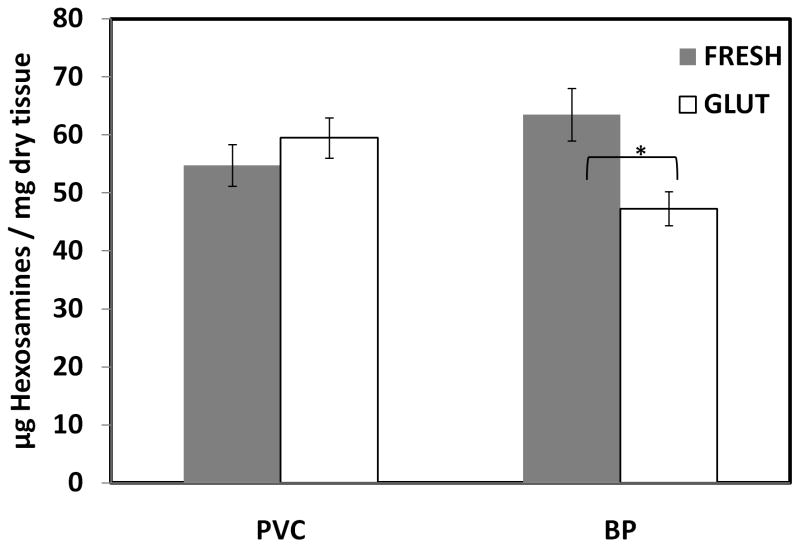

GAG Content

To quantify the GAG content in the tissues, the hexosamine assay is commonly used, as GAGs contain two components—a hexosamine sugar and an uronic acid molecule. In the porcine vena cava tissue, there was no significant difference in hexosamine content between fresh and GLUT samples (Figure 2). In contrast, bovine pericardium showed statistically significant loss of GAGs after GLUT crosslinking [12]. Please note the results express absolute amount of hexosamines including non-GAG-related hexosamines. As the amount of non-GAG-related hexosamines is not known for vena cava and pericardium, only the relative quantity of GAGs in the tissue can be represented.

Figure 2.

GAG content as represented by hexosamine content of tissue; * indicates difference with Fresh of same species; (n = 6; * p<0.05)

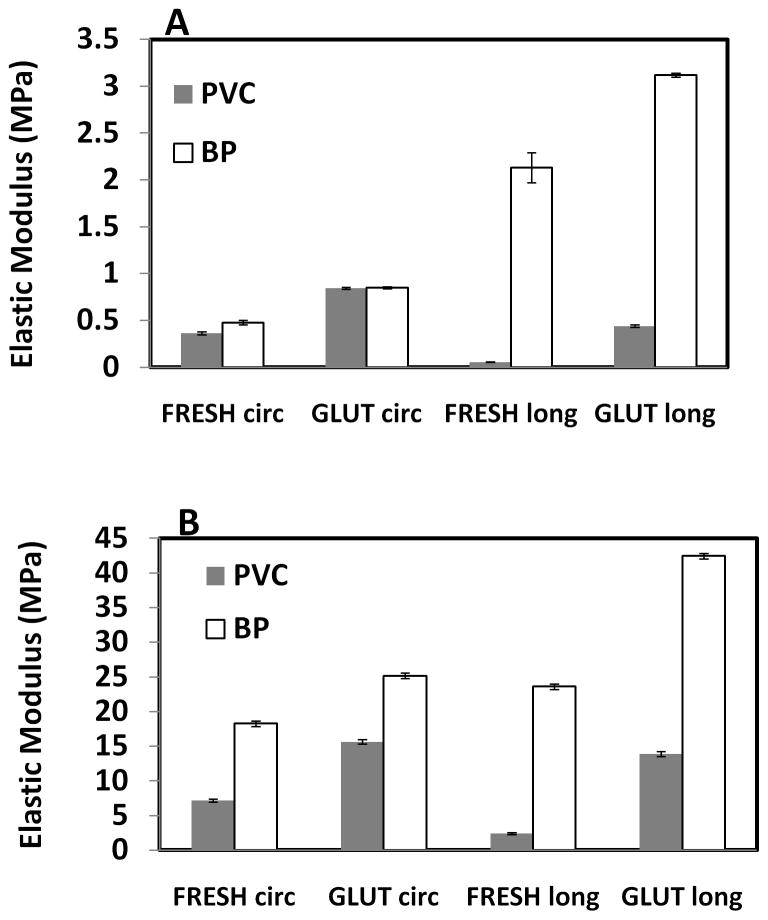

Elastic Modulus

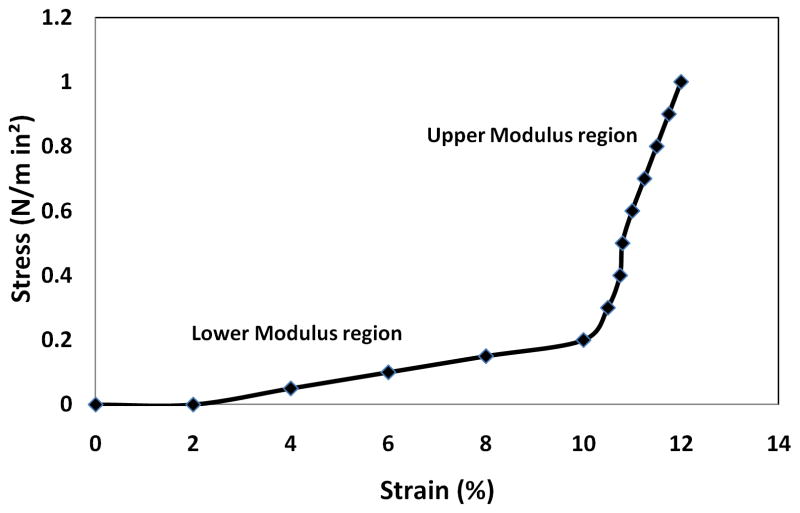

Uniaxial tensile tests were performed on fresh and GLUT fixed PVC and BP in both the longitudinal (long) and circumferential (circ) directions. Uniaxial measurements showed typical toe region (lower modulus) and linear region (upper modulus) stress-strain curves (Figure 3). Since heart valves function in both the elastic (lower modulus) and collagen (upper modulus) regions of the stress-strain curve, elastic moduli for both slopes were calculated.

Figure 3.

Representative uni-axial tensile stress strain curve for porcine vena cava

Fresh PVC was significantly less stiff in the longitudinal direction than the circumferential in both upper and lower modulus regions (Figure 4). BP was significantly stiffer than PVC in all treatment groups. The BP was especially stiff in the longitudinal direction as compared to the vena cava, indicating that the longitudinal alignment of elastin fibers in vena cava greatly lends itself to the tissue compliance. Furthermore, fixation caused a significant increase in stiffness in both tissue types. GLUT tissues were stiffer than fresh samples, likely because of additional crosslinks formed within the tissue.

Figure 4.

Effects of fixation on elastic moduli of porcine vena cava (PVC) and bovine pericardium (BP); (A) Lower modulus; (B) Upper modulus; (n = 6; All differences between PVC and BP are significant (p < 0.05) except GLUT in the lower modulus in circumferential direction)

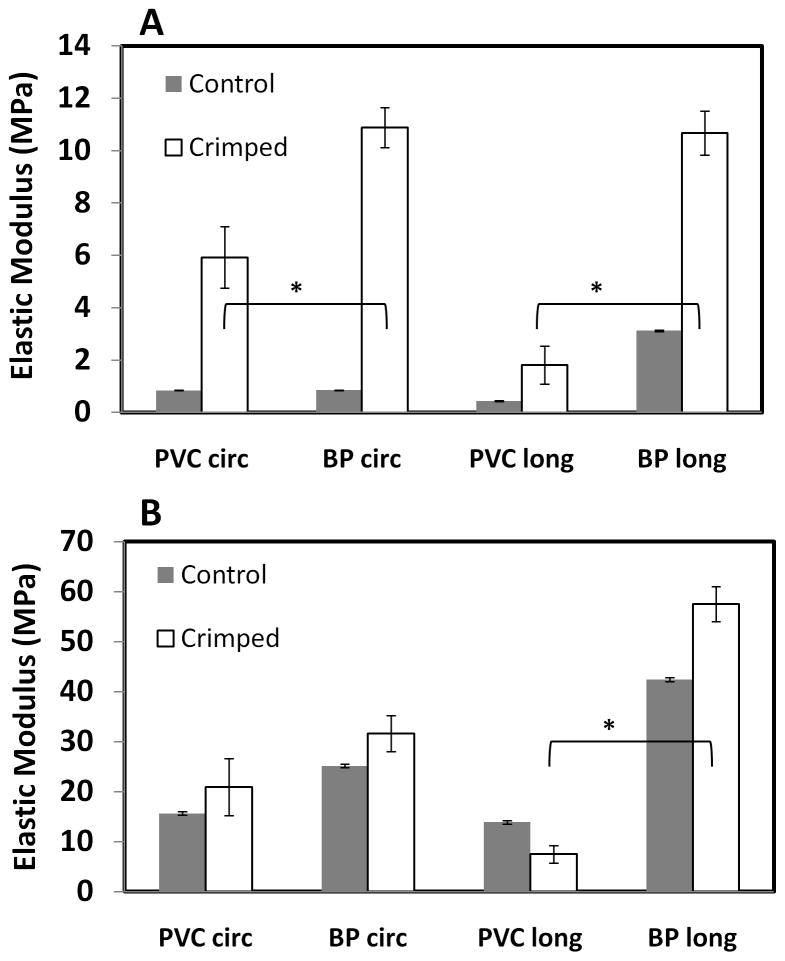

Elastic Modulus of Crimped Tissues

Following crimping, the vena cava and pericardium were subjected to uniaxial tensile tests. The results were compared to uncrimped GLUT controls to determine how the compressive forces experience during crimping affect tissue fibers and mechanical properties (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Elastic modulus of tissue after crimping; A) Lower modulus B) Upper modulus; (n = 6; All differences between uncrimped and crimped tissues are significant (p < 0.05) * indicates difference between crimped PVC and BP tissues, p<0.05)

In the circumferential direction, crimping caused a significant increase in the lower elastic modulus of all tissue groups. Importantly, the GLUT-fixed BP became stiffer than the corresponding PVC after crimping. The effects of crimping were not as obvious in the upper modulus in the circumferential direction, as only GLUT-fixed PVC was significantly stiffer than the control in this group.

The trends in mechanical behavior in the longitudinal direction differed slightly from the circumferential behavior. After crimping, a significant increase in the lower elastic modulus was again seen among all tissue groups. However, the BP became much stiffer than the PVC, reaching a lower elastic modulus of 10,674.43 ± 841.31 kPa, whereas the PVC had a lower modulus of only 1,812.48 ± 732.98 kPa after crimping. Considering the upper modulus, the crimped BP again increased in stiffness as compared to the controls, but the difference was not as great as for the lower modulus. The upper elastic modulus of the PVC decreased in the longitudinal direction, while it increased in BP after crimping thus PVC was less stiff than BP tissue.

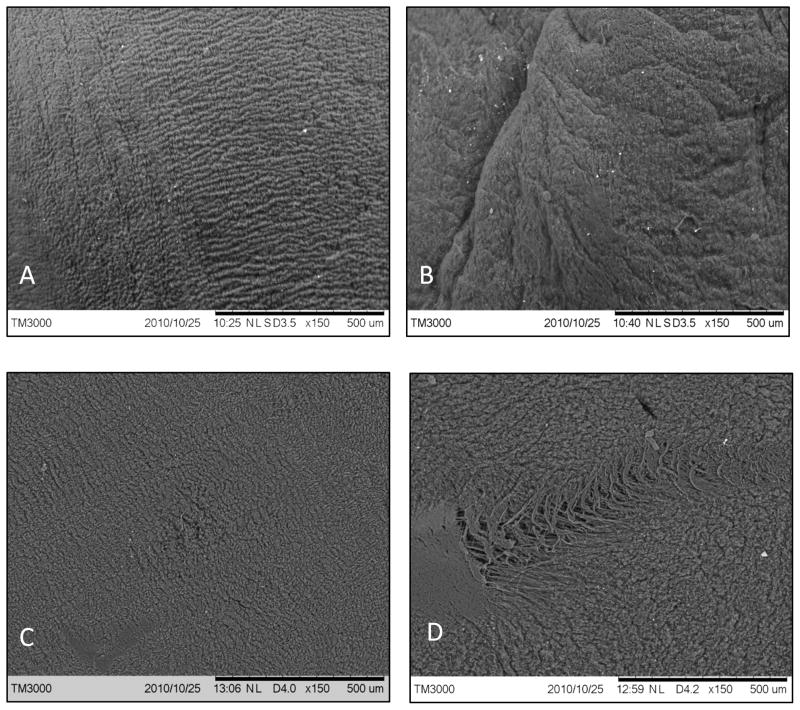

Scanning Electron Microscopy

The surfaces of the crimped tissues were observed with scanning electron microscopy to detect any defects. The adventitial surface of the control vena cava and the outer surface of the control pericardium were very rough, and indentations and striations were impossible to detect (images not shown). However, the smooth intima of PVC and serosa of BP exhibited some surface modifications after crimping. The intimal surface of the control PVC samples (Figure 6) are generally smooth with small grooves spanning uniformly across the surface. After crimping, the GLUT BP tissue exhibited severe cracks, tears, and fiber damage while GLUT PVC only showed a minor increase in folds without any cracks or tears.

Figure 6.

Scanning electron microscopy pictures: A) PVC control; B) PVC crimped; C) BP control; D) BP crimped, bar represents 500 μM.

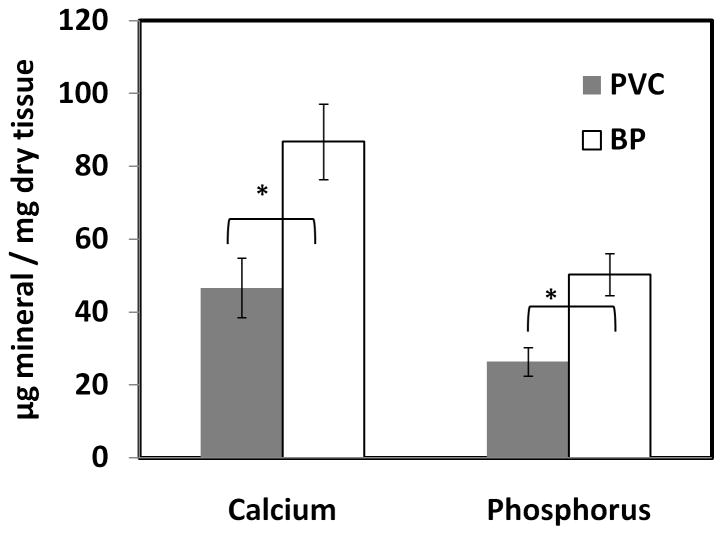

Rat Subdermal Implantation

The juvenile rat subdermal implantion model was used to study the mineralization tendency of the tissues as it exhibits an accelerated calcification response [2]. After 3 weeks of implantation, GLUT-fixed PVC calcified significantly less than BP (Figure 7). Phosphorus content was used as a complement to calcium data, as mineral deposits in heart valves are generally composed of poorly crystalline calcium phosphates. Trends similar to those in the calcium data are observed in the phosphorus results showing lower phosphorus in PVC tissues. Additionally, the Ca:P molar ratio for each sample group was calculated, as this statistic provides information about the organization of the calcium phosphate deposits in the tissue. Both BP and PVC showed similar Ca:P ratios (1.37± 0.04 and 1.33± 0.01 respectively) suggesting deposition of octacalcium phosphate.

Figure 7.

Calcium and phosphorus content of subdermally implanted tissue; (n = 10; * p<0.05)

Discussion

While percutaneous technology is revolutionizing the field of replacement heart valves, these new devices are not without limitations, the most important of which is device profile. The ability to access the heart via a catheter is largely determined by the diameter of the arteries. First generation PHVs were too wide for transcatheter delivery in many patients and necessitated inherently riskier transapical delivery instead. New generations of percutaneous valves are fabricated from glutaraldehyde crosslinked bovine pericardium. This material was chosen by industry due to its traditional use in stented bioprosthetic valves and historical clinical outcome information over several decades. However, whether the tissue remains durable and functional after in-stent crimping is not studied. We found significant alterations in mechanical properties and surface damage to BP tissue after crimping. BP tissues became stiffer after crimping possibly due to permanent alteration is extracellular matrix orientation. We then tested more elastic porcine vena cava tissue. We hypothesized that use of a highly elastic PVC tissue would lead to better tissue recoil after deployment and possibly to a lower device profile.

Tissue Structure

The mechanical properties of bioprosthetic heart valves are largely dictated by the extracellular matrix. In native heart valve leaflets, circumferentially-aligned collagen fibers in the fibrosa support loads during cyclic functioning, while radially-aligned elastin fibers in the ventricularis allow for extensibility and coaptation [13]. Additionally, glycosaminoglycans in the spongiosa help to hydrate the tissue, absorb shock, and dampen the leaflet movement during opening [14]. Thus, the composition and orientation of tissue extracellular matrix components are crucial to proper valve function.

We examined the extracellular matrix components in the tissue quantitatively using enzyme digestion studies. Fresh and fixed tissues were digested in elastase and collagenase, and the percent weight loss was calculated. It was assumed that fresh tissue offered no enzymatic resistance, so the percent weight loss represented the weight fraction of each tissue component. Fresh bovine pericardium lost significantly more weight after collagenase than did porcine vena cava (74.59± 1.01% and 56.86± 3.99% respectively). This result suggests that the pericardial extracellular matrix is more collagen-dense than vena cava ECM. Fixation with glutaraldehyde greatly enhances collagen stability, decreasing the percent weight loss to less than 10% in both tissue types. GLUT forms stable crosslinks with collagen through a Schiff base reaction between its aldehyde group and the amine group on the lysine and hydroxylysine residues of collagen [11]. The crosslinks help prevent enzymatic degradation of the collagen fibers.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measures the collagen denaturation temperature (Td) by monitoring the heat flow in the tissue sample while heating at a set rate. GLUT fixation significantly increased Td, as GLUT-based crosslinks between collagen increase the stability of the fibers. The thermal denaturation temperature of the GLUT vena cava and pericardium is in agreement with previously reported values of 88.3 ± 0.56 °C in GLUT porcine aortic valves [15].

Elastin is the second major component of the tissue extracellular matrix. In the native heart valve, radially-aligned elastin fibers provide tissue extensibility that allows for coaptation during valve closure, as well as elastic recoil between loading cycles [16]. Studies have shown that elastin fibers are vital to proper valve mechanics, and elastin damage in the native heart valve results in tissue elongation, reduced radial extensibility, and increased stiffness [16]. Elastase digestion was used to quantify the proportion of elastin in fresh tissue. Fresh vena cava lost significantly more weight (35.10± 5.47%) after elastase treatment than did bovine pericardium (10.51± 0.76%), which suggests that elastin constitutes a larger proportion of extracellular matrix in PVC. GLUT fixation did not render the tissue more enzyme resistant, as GLUT does not crosslink elastin fibers [16] [17]. Thus, if elastic tissues are chosen for heart valve application, new crosslinkers need to be developed to prevent elastic fiber degradation. It should be noted that the in vitro elastase degradation study is highly accelerated and the amount of elastase in the blood is several fold lower than that tested here. Thus, elastin degradation may not be as significant in actual in vivo heart valve implants. In fact, GLUT crosslinked porcine aortic heart valves used extensively in heart valve applications over the last several decades contain about ten weight percent elastin and no published data shows elastin degradation in explanted valves.

Glycosaminoglycans, the third ECM component, play a large role in heart valve mechanics by hydrating the tissue, dissipating energy, and facilitating shearing between tissue layers [11, 12, 14]. While the role of GAGs in heart valve mechanics is well understood, their function in other vascular tissues, such as the vena cava, has not been elucidated. The PVC tissue did not show any significant loss in hexosamine content after GLUT crosslinking while BP showed substantial loss. We have shown previously that GLUT crosslinking does not stabilize GAGs [18, 19], thus most of the hexosamines in PVC are likely non-GAG-related. Indeed, it has been reported that the quantity of GAGs in the vena cava is quantitatively undetectable [20].

Tissue Mechanics

Extracellular matrix fiber orientation plays a large role in biologic tissue mechanics [13, 21]. For many biological tissues subjected to tensile testing, the stress-strain curve contains two regions: a lower modulus region that is dominated by elastin fibers and an upper modulus region that is dominated by the collagen response [22]. Indeed the stress-strain curves for the vena cava and pericardium displayed the expected two-region behavior. The lower elastic modulus of fresh vena cava was significantly lesser in the longitudinal direction than the circumferential, indicating longitudinal alignment of the elastin fibers. The upper modulus was greater in the circumferential direction due to the circumferentially-aligned collagen fibers.

Conversely, the longitudinal upper and lower moduli of the fresh bovine pericardium were greater than the circumferential moduli. This result suggests that the elastin fibers of the pericardium tend to be aligned more toward the circumferential direction, which would allow outward extensibility of the pericardial sac as the heart beats. However, the differences in circumferential and longitudinal lower moduli in the pericardial tissue were not as profound as those of the vena cava, suggesting that the elastin fibers are not as highly aligned in the pericardium. Similarly, the upper moduli of the fresh pericardium also did not differ as starkly in the circumferential and longitudinal directions as those of the vena cava, confirming a more random orientation of collagen fibers in the pericardium. The varied collagen alignment serves to provide strength to the pericardium in multiple directions, as the sac must withstand a number of different forces, including outward tension and torsion during the cardiac cycle [23]. However, this diverse alignment causes variations in mechanical properties that may not be ideal for constructing a percutaneous heart valve.

The tissue fixation process has also been shown to have a significant effect on tissue mechanics [11]. Chemical crosslinking of the collagen matrix improves tissue stability, but also hinders fiber movement, leading to increased tissue stiffness [24–26]. GLUT fixation increased the upper and lower moduli of both the vena cava and pericardium, due to crosslink formation. While the upper and lower moduli of the two tissue types were only modestly different in the circumferential direction, the pericardium was enormously stiffer than the vena cava in the longitudinal direction, a result which was exacerbated by GLUT crosslinking. The higher collagen content of the pericardium was more affected by crosslinking, resulting in very high upper elastic moduli for fixed pericardium. Conversely, since GLUT does not crosslink elastin [12], the vena cava was able to retain much of its flexibility, especially in the lower modulus region. Increased stiffness following crosslinking is cited as a major contributor to bioprosthetic valve mechanical failure [11]. Use of vena cava in valve construction may therefore improve prosthesis durability by enhancing bioprosthetic tissue flexibility.

Tissue Resilience

The main advantage of percutaneous heart valves is their ability to be implanted without open chest surgery. The unique PHV design allows the entire valve to be crimped into a small diameter and delivered via a transcatheter route to the aortic position [6]. However, this design feature also raises concerns about the integrity of the crimped tissue [27]. Stents are crimped under large compressive forces. Subjecting the tissue to excessive loads prior to implantation may alter the mechanical properties, damage the implant surface, or harm extracellular matrix fibers. Thus, the response of the vena cava and pericardium to compression was studied.

SEM images showed that the intima of GLUT vena cava was affected by crimping, as new folds were apparent in the crimped tissues. However, more dents, markings, and fiber tears were apparent on the serosa of the pericardium. These results suggest that crimping in a stent alters the surface topography of both vena cava and pericardium, and pressure from the stent struts may cause damage to the tissue surfaces albeit more noticeable in BP. A rough surface on the inflow surface of the valve can potentiate thrombosis formation [2], so the smooth tissue surfaces should be oriented inward and the crimping process carried out in such a way as to minimize compressive pressure from the stent struts on the inner surface.

Loading has been shown to cause changes in tissue mechanics [13, 21]; thus the elastic modulus of the crimped tissue was compared to that of the controls. Crimping increased the lower elastic modulus for all tissue types, suggesting that the compressive force stiffened the tissue. The lower modulus is dominated by the response of the elastin fibers. The increase in lower modulus was especially evident in the circumferential direction. Applied stress causes fiber realignment in the direction of the force to help the tissue bear the load [21]. The elastin fibers may have realigned circumferentially to increase the stiffness in that direction. The increase in lower modulus in the longitudinal direction was significantly lower for the vena cava, and is likely due to the elastin fibers uncrimping under the load, causing slight stiffening of the tissue [13]. The increase in stiffness in the longitudinal direction is greater for the pericardium, possibly because the lower elastin content and lesser alignment of elastin fibers in BP. They do not all react to the load uniformly by realigning to the same degree in the same direction.

The upper elastic modulus is dominated by collagen fibers, which uncrimp and realign in response to an applied load. The upper elastic modulus in the circumferential direction for most of the tissue groups did not show a significant increase after compression. However, the GLUT vena cava had a slight increase in modulus in this orientation. Conversely, in the longitudinal direction, the vena cava exhibited a decrease in the upper elastic modulus while the pericardium exhibited an increase. The results suggest that the collagen fibers of the vena cava realigned in the circumferential direction, causing stiffening circumferentially. The tissue is less stiff in the longitudinal direction because fewer fibers are available to bear the load. For the pericardium, the increase in upper modulus in the longitudinal direction was small, suggesting that some of the randomly-oriented collagen fibers realigned longitudinally. In summary, the crimped vena cava samples were less stiff than the corresponding pericardium samples, especially in the longitudinal direction. After crimping, the vena cava maintained its mechanical directionality, exhibiting greater compliance in the longitudinal direction than the circumferential. Thus, the crimping process does not negate the mechanical benefits offered by the vena cava.

In vivo calcification

One of the major failure modes of glutaraldehyde crosslinked bioprosthetic heart valves is calcification of the tissue. Calcium deposits form hard nodules on the cusps or aortic wall that can lead to cuspal tears or stenosis [28]. Calcification is often cell-related, as glutaraldehyde devitalizes cells, eliminating active calcium regulation processes [29]. Upon exposure to body fluids, intracellular calcium levels in the bioprostheses rise dramatically, and calcium deposits form on the phospholipid-rich membranes and organelles [30]. Extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen and elastin have also been noted as secondary nucleation sites [31]. The calcium deposits eventually aggregate to form hard, sharp nodes that can stiffen or perforate the tissue [29].

GLUT vena cava and pericardium samples were implanted into juvenile Sprague Dawley rats. After three weeks, GLUT vena cava exhibited significantly less calcification than GLUT pericardium, possibly due to differences in cell density between the tissue types or due to differences in tissue ECM. Additionally, the Ca:P molar ratio of the mineralized explants was calculated, as different types of calcium phosphate contain varying proportions of these elements [32]. Poorly crystalline hydroxyapatite (HAP), which comprises bone, has a Ca:P ratio of 1.67, while precursor phases such as octacalcium phosphate (OCP) and dicalcium phosphate dehydrate (DCPD) have ratios of 1.33 and 1.00, respectively. HAP formation is thought to be a process of phase transitions from transient forms of calcium phosphate, such as DCPD, to OCP, and finally to mature, stable HAP. Based on the calculated Ca:P ratios, the calcium phosphate deposits in GLUT vena cava and pericardium are likely to be OCP.

Conclusions

The results of our studies clearly show that vena cava has several advantages over pericardium. While the two tissues are equal in collagen stability, the vena cava has significantly higher elastin content, a factor which imparts enhanced flexibility to the tissue. Moreover, the elastin and collagen fibers in the vena cava are highly aligned, resulting in mechanical directionality and consistency. In contrast, the pericardium has more randomly oriented extracellular matrix containing more collagen and less elastin, yielding a stiffer tissue with less predictable mechanical properties. Improved mechanical properties were also noted after fixation with the pericardium stiffening drastically after GLUT fixation, and the vena cava retaining much of its flexibility. Although after crimping, both the GLUT vena cava and pericardium exhibited surface changes, BP showed more severe surface cracks than PVC. Additionally, the vena cava experienced a less significant change in elastic modulus after crimping, further suggesting that the tissue may be more resilient to the compressive forces imparted by a stent. Finally, the vena cava exhibited less calcification than the pericardium. Future studies should aim to further reduce tissue mineralization, and evaluate the fatigue response of each tissue type.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by NIH grants HL 70969 and P20RR021949.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sacks MS, David Merryman W, Schmidt DE. On the biomechanics of heart valve function. J Biomech. 2009;42:1804–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoen FJ, Levy RJ. Founder’s Award, 25th Annual Meeting of the Society for Biomaterials, perspectives. Providence, RI, April 28-May 2, 1999. Tissue heart valves: current challenges and future research perspectives. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;47:439–65. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19991215)47:4<439::aid-jbm1>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Culliford AT, Galloway AC, Colvin SB, Grossi EA, Baumann FG, Esposito R, et al. Aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis in persons aged 80 years and over. Am J Cardiol. 1991;67:1256–60. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90937-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kvidal P, Bergstrom R, Horte LG, Stahle E. Observed and relative survival after aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:747–56. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00584-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pai RG, Kapoor N, Bansal RC, Varadarajan P. Malignant natural history of asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis: benefit of aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:2116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiam PT, Ruiz CE. Percutaneous transcatheter aortic valve implantation: Evolution of the technology. Am Heart J. 2009;157:229–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grube E, Schuler G, Buellesfeld L, Gerckens U, Linke A, Wenaweser P, et al. Percutaneous aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis in high-risk patients using the second- and current third-generation self-expanding CoreValve prosthesis: device success and 30-day clinical outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597–607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silver FH, Snowhill PB, Foran DJ. Mechanical behavior of vessel wall: A comparative study of aorta, vena cava, and carotid artery. Ann Biomed Eng. 2003;31:793–803. doi: 10.1114/1.1581287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samouillan V, Dandurand J, Lacabanne C, Thoma RJ, Adams A, Moore M. Comparison of chemical treatments on the chain dynamics and thermal stability of bovine pericardium collagen. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2003;64A:330–8. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah SR, Vyavahare NR. The effect of glycosaminoglycan stabilization on tissue buckling in bioprosthetic heart valves. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1645–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.12.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raghavan D, Starcher BC, Vyavahare NR. Neomycin binding preserves extracellular matrix in bioprosthetic heart valves during in vitro cyclic fatigue and storage. Acta Biomaterialia. 2009;5:983–92. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joyce EM, Liao J, Schoen FJ, Mayer JE, Jr, Sacks MS. Functional collagen fiber architecture of the pulmonary heart valve cusp. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:1240–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.12.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friebe VM, Mikulis B, Kole S, Ruffing CS, Sacks MS, Vyavahare NR. Neomycin enhances extracellular matrix stability of glutaraldehyde crosslinked bioprosthetic heart valves. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31889. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vyavahare N, Hirsch D, Lerner E, Baskin JZ, Schoen FJ, Bianco R, et al. Prevention of bioprosthetic heart valve calcification by ethanol preincubation. Efficacy and mechanisms. Circulation. 1997;95:479–88. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee TC, Midura RJ, Hascall VC, Vesely I. The effect of elastin damage on the mechanics of the aortic valve. J Biomech. 2001;34:203–10. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00187-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee CH, Vyavahare N, Zand R, Kruth H, Schoen FJ, Bianco R, et al. Inhibition of aortic wall calcification in bioprosthetic heart valves by ethanol pretreatment: biochemical and biophysical mechanisms. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;42:30–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199810)42:1<30::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simionescu DT, Lovekamp JJ, Vyavahare NR. Glycosaminoglycan-degrading enzymes in porcine aortic heart valves: implications for bioprosthetic heart valve degeneration. J Heart Valve Dis. 2003;12:217–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vyavahare N, Ogle M, Schoen FJ, Zand R, Gloeckner DC, Sacks M, et al. Mechanisms of bioprosthetic heart valve failure: fatigue causes collagen denaturation and glycosaminoglycan loss. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;46:44–50. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199907)46:1<44::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer GM, Swain ML, Cherian K. Increased vascular collagen and elastin synthesis in experimental atherosclerosis in the rabbit. Variation in synthesis among major vessels. Atherosclerosis. 1980;35:11–20. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(80)90023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sellaro TL, Hildebrand D, Lu Q, Vyavahare N, Scott M, Sacks MS. Effects of collagen fiber orientation on the response of biologically derived soft tissue biomaterials to cyclic loading. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2007;80:194–205. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vannoort R, Yates SP, Martin TRP, Barker AT, Black MM. A Study of the Effects of Glutaraldehyde and Formaldehyde on the Mechanical-Behavior of Bovine Pericardium. Biomaterials. 1982;3:21–6. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(82)90056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zioupos P, Barbenel JC. Mechanics of native bovine pericardium. II. A structure based model for the anisotropic mechanical behaviour of the tissue. Biomaterials. 1994;15:374–82. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(94)90250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schoen FJ. Evolving concepts of cardiac valve dynamics: the continuum of development, functional structure, pathobiology, and tissue engineering. Circulation. 2008;118:1864–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.805911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vesely I, Boughner D, Song T. Tissue buckling as a mechanism of bioprosthetic valve failure. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;46:302–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)65930-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher J, Davies GA. Buckling in bioprosthetic valves. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989;48:147–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(89)90211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McRae ME, Rodger M, Bailey BA. Transcatheter and transapical aortic valve replacement. Crit Care Nurse. 2009;29:22–37. doi: 10.4037/ccn2009553. quiz 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siddiqui RF, Abraham JR, Butany J. Bioprosthetic heart valves: modes of failure. Histopathology. 2009;55:135–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schoen FJ, Levy RJ. Heart valve bioprostheses: antimineralization. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1992;6(Suppl 1):S91–3. discussion S4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim KM, Herrera GA, Battarbee HD. Role of glutaraldehyde in calcification of porcine aortic valve fibroblasts. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:843–52. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65331-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Golomb G, Schoen FJ, Smith MS, Linden J, Dixon M, Levy RJ. The role of glutaraldehyde-induced cross-links in calcification of bovine pericardium used in cardiac valve bioprostheses. Am J Pathol. 1987;127:122–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mavrilas D, Apostolaki A, Kapolos J, Koutsoukos PG, Melachrinou M, Zolota V, et al. Development of bioprosthetic heart valve calcification in vitro and in animal models: morphology and composition. J Cryst Growth. 1999;205:554–62. [Google Scholar]