Abstract

Delivering growth factors from bone-like mineral combines osteoinductivity with osteoconductivity. The effects of individual and sequential exposure of BMP-2 and FGF-2 on osteogenic differentiation, and their release from apatite were studied to design a dual delivery system. Bone marrow stromal cells were seeded on TCPS with the addition of FGF-2 (2.5, 10, 40 ng/ml) or BMP-2 (50, 150, 450 ng/ml) for 6 days and DNA content, and osteogenic response were examined weekly for 3 weeks. FGF-2 increased DNA content; however, high concentrations of FGF-2 inhibited/delayed osteogenic differentiation, while a threshold concentration of BMP-2 was required for significant osteogenic enhancement. The sequence of delivery of BMP-2 (300 ng/ml) and FGF-2 (2.5 ng/ml) also had a significant impact on osteogenic differentiation. Delivery of FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 or delivery of BMP-2 followed by BMP-2 and FGF-2 enhanced osteogenic differentiation compared to the simultaneous delivery of both factors. Release of BMP-2 and FGF-2 from bone-like mineral was significantly affected by the concentration used during coprecipitation. BMP-2 also demonstrated a higher “burst” release compared to FGF-2. By integrating the results of the sequential delivery of BMP-2 and FGF-2 in solution, with the release of individual growth factors from mineral, an organic/inorganic delivery system based on coprecipitation can be designed for multiple biomolecules.

Keywords: coprecipitation, biomineralization, biomimetic material, SBF (simulated body fluids), BMP, FGF

1. Introduction

The clinical basis for bone regeneration is the correction of bone defects caused from trauma, congenital malformations, and progressively deforming skeletal disorders. Bone tissue engineering provides an alternative to bone grafting and direct usage of growth factors to regenerate bone. Bone tissue engineering uses engineering design to strategically integrate cells, an extracellular matrix (ECM) analogue, and signaling molecules to induce bone regeneration in a controlled and predictable manner [1]. An ideal bone tissue engineering approach would incorporate osteoinductivity and osteoconductivity into the design of the supporting biomaterial, as well as biocompatibility, degradability, mechanical integrity, and the ability to support cell transplantation.

Osteoinductive properties can be integrated into a tissue engineering system by immobilization of biomolecules to a biomaterial surface, or encapsulation within a biomaterial. Employing an inductive approach to bone regeneration in the form of growth factors can regulate cellular responses (proliferation, migration, differentiation), and have either synergistic or antagonistic effects on other growth factors. Although the activation of a single growth factor can have an impact on several signaling pathways, in the cellular environment, signaling is not limited to a single growth factor but a multitude of growth factors at different locations and times. Therefore, in developing a delivery system to better simulate the microenvironment that cells are subjected to in vivo, exposure to multiple biological cues with spatial and temporal gradients would be advantageous. For example, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) alone is not sufficient to heal critical size defects, however combining VEGF with bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP-4) enhances healing [2]. In some instances, delivering multiple factors together may not be sufficient to effect a biological response [3]. Simultaneous exposure of rat BMSCs to insulin growth factor-I (IGF-I) and BMP-2 does not increase alkaline phosphatase expression or calcium secretion, but exposure of cells to BMP-2 followed by IGF-I does increase osteogenic differentiation, demonstrating the importance of timing and the sequence of delivery of the growth factors on cell response [4].

To provide the design parameters for the development of a delivery system for bone engineering, BMP-2 and fibroblastic growth factor 2 (FGF-2) were chosen due to their important roles in osteogenic differentiation. BMPs regulate the growth and differentiation of cells in the osteoblast lineage. In vitro, rhBMP-2 not only induces differentiation of osteoblastic precursors [5], but it also inhibits myogenic differentiation [6]. BMP-2 is one of the earliest genes that is induced in fracture healing, with a second peak occurring late in the period of osteogenesis [7], which suggests that a simple burst release or sustained release may not be optimal to elicit an osteogenic response.

Fibroblast growth factors promote cell growth, induce a mitogenic response, stimulate cell migration, and induce differentiation [8]. FGF-2 is a well known angiogenic factor, and at lower concentrations, it also plays a role in osteogenic differentiation. FGF-2 can stimulate the replication of osteoprogenitor cells, which then further differentiate into an osteoblastic phenotype. However, FGF-2 can also inhibit bone formation at specific concentrations (100 ng/ml) and durations (24–96 h) [9]. Because both BMP-2 and FGF-2 regulate osteogenesis, they have been used in combination. FGF-2 stimulates cell growth and osteoblastic differentiation of dexamethasone treated MSCs, and upon exposing cells to both BMP-2 and FGF-2, bone formation is enhanced more than either growth factor individually [10], confirming the importance of temporal gradients.

Osteoconductivity is derived from surface and bulk properties of synthetic or natural materials, which allow the recruitment of targeted host cells while preventing unwanted cells from entering the cellular microenvironment. To ideally deliver multiple biomolecules, an osteoconductive/osteoinductive delivery system must be developed that allows for temporal control over release. Polymeric dual delivery systems have been developed that are based on the fusion of a polymer containing one biomolecule with microspheres containing a second biomolecule, where release is controlled by polymer degradation [11]. Another approach is to coat a scaffold with hydrogel copolymers containing biomolecules, where the release of biomolecules is based on diffusion through the different hydrogel layers [12]. However, protein aggregation within the hydrogel can occur, resulting in incomplete release [12]. A third approach uses a peptide-modified alginate hydrogel, where multiple factors are delivered in conjunction with cells to induce ectopic bone formation. However, the sequence of delivery is not controlled [13].

An alternative to polymeric systems is the coprecipitation of proteins with biomimetic apatite onto an implant or scaffold surface. In addition to providing spatial-temporal control over delivery like many polymer systems, bioceramic coatings provide a high degree of osteconductivity. The formation of a bone-like mineral layer in vivo leads to interfacial bonding between implants and bone [14]. The synthesis of a bone-like mineral layer may enhance the conduction of host cells into scaffolds [15], in addition to inducing osteogenic differentiation of cells transplanted [16]. Additionally, the apatite increases stiffness, a design parameter not provided by polymer systems capable of temporal delivery. Substrate stiffness can have effects on DNA uptake, cell structure, and protein expression [17, 18]. An important advantage to coprecipitation is the ability to produce calcium phosphate coatings at a physiological temperature [19, 20], minimizing conditions that would alter the biological activity of the factors [21]. Biomolecules can be incorporated at different stages of the deposition of the calcium phosphate coatings [21], which spatially localizes the biomolecule through the apatite thickness [22], thus impacting release. Delivering the growth factors from a mineralized substrate is a tissue engineering approach that combines osteoinductivity, provided by the inclusion of the growth factors, and osteoconductivity, provided by the presence of biomimetically precipitated apatite.

The effects of individual and sequential exposure of BMP-2 and FGF-2 on osteogenic differentiation of murine BMSCs were examined in conjunction with the individual release kinetics of BMP-2 and FGF-2 coprecipitated within biomimetic apatite to build toward the long term objective of utilizing biomineralization to deliver multiple growth factors in a controlled manner. It was hypothesized that low concentrations of FGF-2 would increase cell number while high concentrations of BMP-2 would enhance osteogenic differentiation. It was also hypothesized that the sequence of FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 would best enhance the osteogenic activity of the BMSCs compared to the delivery of each of the growth factors independently. DNA content, alkaline phosphatase activity (ALP), osteocalcin serum content, and mineralization were analyzed over 3 weeks. To determine growth factor concentrations needed to promote BMSC growth and differentiation, cells were seeded on TCPS with the addition of FGF-2 (0, 2.5, 10, 40 ng/ml) or BMP-2 (0, 50, 150, 450 ng/ml). To determine the effects of sequential administration on BMSC growth and differentiation, 2.5 ng/ml of FGF-2 and 300 ng/ml of BMP-2 were used. Coprecipitation schemes were then designed to mimic the concentration and sequence of FGF-2 and BMP-2 that optimally differentiated the cells. BMP-2 and FGF-2 were incorporated within apatite during the coprecipitation process and the release of these factors was examined using ELISA. It was hypothesized that the release profiles of BMP-2 and FGF-2 would be dependent on the growth factor concentration in supersaturated ionic solution during coprecipitation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Murine bone marrow stromal cell extraction and cell culture

Six week old C57BL6 mice were utilized for BMSC extraction. Freshly extracted long bones (6 per mouse) were suspended in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS). The metaphyses of each bone were cut, and 2 bones were placed into a 200 μl pipette tip which was placed in a microcentrifuge tube. Tubes were spun for 8–12 sec up to a maximum speed of 2000 rpm [23]. An 18 gauge needle was used to gently agitate the cell pellets. Cell pellets were then pooled and split into T75 flasks. Media was exchanged and non-adhesive cells were removed after 5 days. Media was then exchanged every 3 days until cells reached confluency, at which time cells were split 1:3 and replated. After reaching confluency, cells were counted and replated in 24 well plates.

Growth medium for primary cell culture and plating was composed of 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and MEMα. During growth factor administration, the growth medium was supplemented with 10−8 M dexamethasone for six days. After this time period, osteogenic medium was utilized, which was growth medium supplemented with dexamethasone, 50 mg/L L-ascorbic acid-phosphate, and 10 mM β-glycerol phosphate hydrate disodium salt.

2.2 Growth factors and heparin

The growth factors rhBMP-2 and rhFGF-2 were obtained from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). FGF-2 was reconstituted in 5 mM Tris buffer containing bovine serum albumin (BSA). BMP-2 was reconstituted in sterile water containing BSA. Heparin sodium salt derived from porcine intestinal mucosa was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

2.3 Single growth factor optimization

Cells were plated into 24 well-plates (n=4 per group) at a density of 40,000 cells per well and allowed to attach for 24 h. Medium was then removed and replaced with growth medium containing dexamethasone and growth factor (FGF-2 at 0, 2.5, 10, and 40 ng/ml or BMP-2 at 0, 50, 150, and 450 μg/ml), which was designated as Day 1. The media containing growth factor was replaced on Day 4. On Day 7, and every 3 days thereafter, the medium was replaced with osteogenic medium.

2.4 Multiple growth factor optimization

Cells were plated into 24 well-plates (n=4 or 5 per group) at a density of 50,000 cells per well and allowed to attach for 24 h. Medium was then removed and replaced with growth medium containing dexamethasone and growth factors on Days 1 and 4 (Table 1). On Day 7, and every 3 days thereafter, the medium was replaced with osteogenic medium.

Table 1.

List of growth factor sequences. On Day 1, the growth factor(s) in media is added to cells. On Day 4, the media is removed and new media containing the new growth factor(s) is/are added.

| Growth Factor Administration | ||

|---|---|---|

| Abbreviations | Day 1 | Day 4 |

| Untreated | None | None |

| B/B | BMP-2 | BMP-2 |

| B/F | BMP-2 | FGF-2 |

| B/BF | BMP-2 | BMP-2 & FGF-2 |

| F/F | FGF-2 | FGF-2 |

| F/B | FGF-2 | BMP-2 |

| F/BF | FGF-2 | BMP-2 & FGF-2 |

| BF/BF | BMP-2 & FGF-2 | BMP-2 & FGF-2 |

2.5 DNA content

To determine DNA content and ALP activity, cells were washed twice with HBSS and harvested utilizing a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.2% Igepal, and 2 mM PMSF in ethanol. Samples were then placed at −80°C for later analysis.

For DNA determination, samples were thawed, and homogenized on ice. Samples were then centrifuged at 12,500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The Quant-iT Picogreen kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used to determine DNA content according to the protocol adapted from the manufacturer. Samples were prepped in duplicate, fluorescence (480 nm excitation and 520 nm emission) was determined using a microplate reader, and DNA quantity was determined by using standard curves. DNA content was determined at days 8, 15 and 22.

2.6 Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity

Thawed homogenized samples were vortexed with assay buffer (glycine, MgCl2), harvest buffer, and p-nitrophenyl-phosphate (PnPP) substrate solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction was terminated by adding 0.1 N NaOH and samples were placed in a 96 well-plate. A standard curve using alkaline phosphatase from calf intestine (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) was used to compare ALP expression and absorbance was determined at 405 nm. Values were then normalized to DNA content. ALP activity was determined at days 8, 15 and 22.

2.7 Osteocalcin (OCN) content

Media was removed and frozen every 3 days in microcentrifuge tubes. Serum OCN content was determined using a mouse OCN EIA kit (Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were thawed and placed into the 96 well-plate. A standard curve was prepared ranging from 0 to 50 ng/ml. After reaction termination, the absorbance was measured at 450 nm immediately.

2.8 von Kossa Staining

To determine extent of mineralization, cell cultures were stained with silver nitrate at days 15 and 22. Briefly, media was removed from the wells, and submerged in Z-fix for 30 min. The wells were gradually rehydrated using EtOH/H2O mixtures, and then rinsed with H2O. The wells were exposed to UV light, stain was removed, and wells were imaged using a dissection microscope. Image analysis of % stained area was obtained using ImageJ (NIH).

2.9 PLGA film preparation

Films were prepared using 5 wt. % PLGA, 85:15 PLA:PGA ratio (Alkermes), in chloroform solution. The films (approximately 200–300 μm thick) were cast onto 15 mm round glass coverslips, covered with aluminum foil and air dried for at least 24 hours under a fume hood. Films were etched in 0.5 M NaOH for 7 minutes and rinsed thoroughly with Millipore water.

2.10 Modified simulated body fluid

A modified simulated body fluid (mSBF, which contains 2X the concentration of Ca2+ and HPO42− as standard SBF) was used to mineralize the films [22]. mSBF consists of the following reagents dissolved in Millipore water: 141 mM NaCl, 4.0 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgSO4, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 4.2 mM NaHCO3, 5.0 mM CaCl2·2H2O, and 2.0 mM KH2PO4. mSBF was prepared at 25°C and titrated to pH 6.8 using NaOH to avoid homogeneous precipitation of calcium phosphate.

2.11 Mineralization and BMP-2 and FGF-2 coprecipitation

For mineralization, samples were incubated in mSBF at 37°C. mSBF was exchanged every 24 h. Samples were mineralized between 6–8 days before coprecipitation. Before coprecipitation, mineralized films were sterilized under UV light for 30 min.

For coprecipitation, mineralized films were placed into a new petri dish. mSBF solution containing either BMP-2 (0, 0.5, 5 μg/ml) or FGF-2 (0, 0.01, 0.05 μg/ml) and heparin (1:1 mass ratio with FGF-2) was placed into each dish containing the premineralized films. The films were incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Samples containing neither BMP-2 nor FGF-2 were mineralized for 24 h at 37°C in mSBF.

2.12 BMP-2 and FGF-2 release kinetics

Samples (n=7) were placed into 24 well plates. One ml of calcium free PBS (BMP-2) or 1 ml PBS with 0.1% BSA (FGF-2) was placed into each well and gently agitated at ca. 75 rpm. PBS or PBS/BSA was replaced at 0.25, 1, 3, 7, and 14 d. Samples were frozen for later analysis.

ELISA (Antigenix America, Huntington Station, NY) was used to analyze the release of BMP-2 and FGF-2. Kits were adapted for each growth factor and optimized for sample analysis. Briefly, tracer antibody was reconstituted in 0.1% BSA solution. BMP-2 and FGF-2 standard curves were prepared using diluent composed of 0.1% BSA and 0.05% Tween 20. Samples were diluted and added in duplicate. Color development was examined at 450 nm with a plate correction at 650 nm after stop solution was added.

2.13 Statistical analysis

Separate one way ANOVAs were used to analyze DNA content, ALP activity, OCN content, and % area coverage of von Kossa stain with regards to growth factor concentration and growth factor sequence. Tukey or Dunnett’s T3 post hoc comparison tests were used for pairwise comparisons. ANOVAs with repeated measures were used to examine the concentrations of BMP-2 and FGF-2 released with respect to growth factor concentrations in mSBF.

3. Results

3.1 Effects of BMP-2 and FGF-2 on DNA content

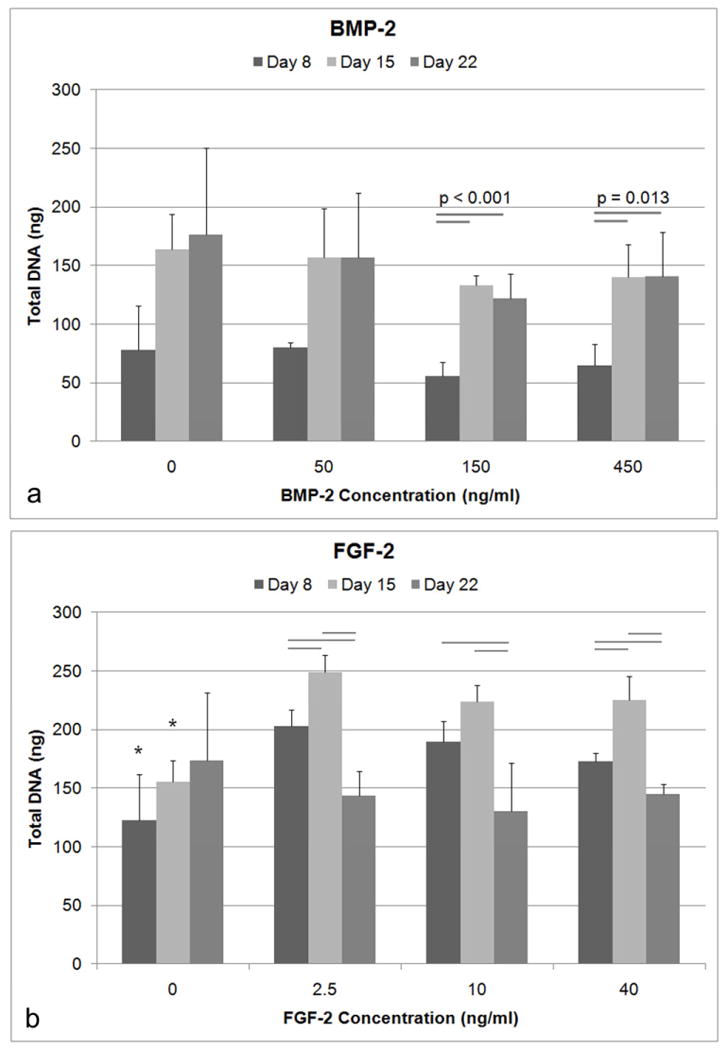

The addition of varying concentrations of BMP-2 to BMSCs did not have a significant effect on DNA content (Figure 1a). For 150 and 450 ng/ml of BMP-2, DNA content increased significantly from Day 8 to Day 15 (p<0.001 and p=0.013 respectively). The addition of FGF-2 to BMSCs had a significant positive effect on DNA synthesis (Figure 1b). At Day 8 (ANOVA, p=0.002) and Day 15 (ANOVA, p<0.001), there was significantly higher DNA content for cells treated with all concentrations of FGF-2 compared to the untreated controls. However, there was not a significant dose dependent response with increasing FGF-2 concentration from 2.5 ng/ml to 40 ng/ml. For 2.5 and 40 ng/ml of FGF-2, DNA levels were significantly higher at Day 15 compared to Day 8 (p<0.05). At Day 22, DNA levels were significantly lower for all FGF-2 concentrations compared to their respective DNA levels at Day 8 (p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Total DNA quantified using Picogreen. A) There was no significant difference in DNA amounts with varying concentrations of BMP-2 (n=4) as determined by ANOVA at the respective timepoints. B) All concentrations of FGF-2 demonstrated higher DNA content compared to the untreated cells for Day 8 and Day 15 (* indicates p<0.05) as determined by ANOVA at the respective time points. The bars represent significance between timepoints within the same concentration treatment.

3.2 Effects of BMP-2 and FGF-2 on ALP activity

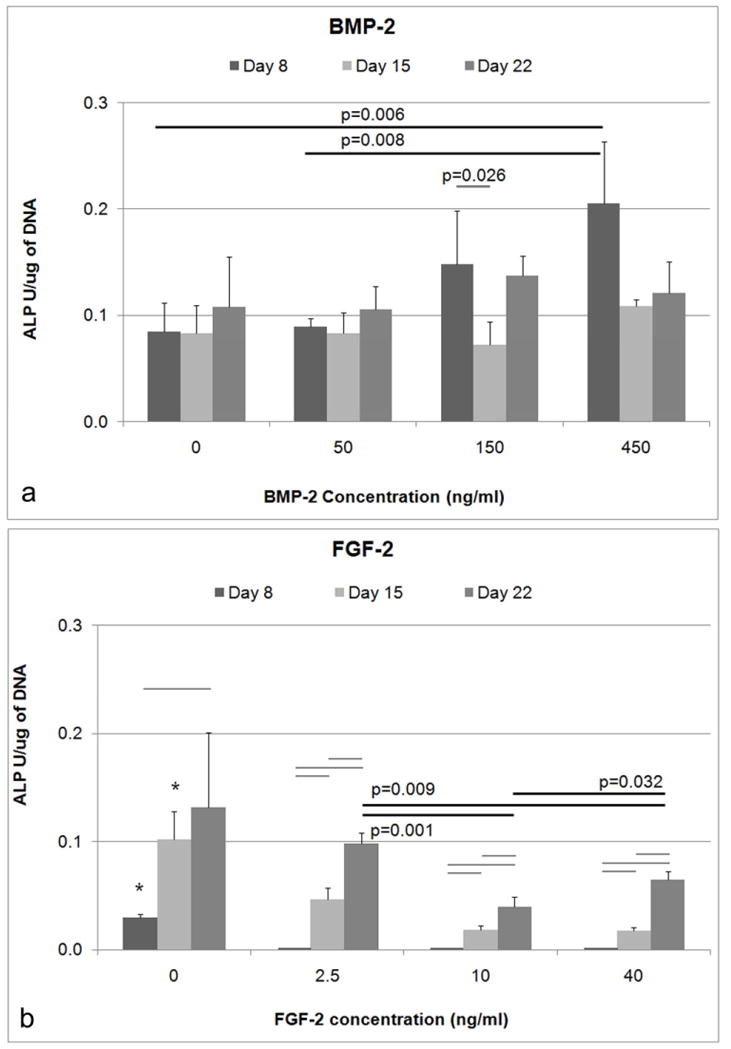

At Day 8, there was a significant effect of BMP-2 concentration on ALP activity (normalized to DNA content; ANOVA, p=0.004). ALP was significantly higher for cells treated with 450 ng/ml BMP-2 compared to both the untreated controls (Tukey, p=0.006) and cells treated with 50 ng/ml BMP-2 (Tukey, p=0.008) (Figure 2a). A lower concentration of BMP-2 (150 ng/ml) did not result in significantly higher amounts of ALP activity compared to untreated controls, suggesting a minimum concentration has to be reached before osteogenic enhancement occurs.

Figure 2.

Normalized ALP with respect to total DNA. A) At Day 8, a BMP-2 concentration of 450 ng/ml led to significantly higher ALP expression compared to the untreated controls. The BMP-2 concentration of 450 ng/ml was also significantly higher than the 50 ng/ml BMP-2 concentration. B) The normalized ALP of untreated controls was higher compared to all concentrations of FGF-2 for Day 8 and Day 15 (* indicates p<0.05) as determined by ANOVA at the respective timepoints. The normalized ALP on Day 22 was also higher for the 2.5 ng/ml concentration compared to both 10 ng/ml and 40 ng/ml (Bars indicates p<0.05).

FGF-2 also had a significant effect on ALP activity (ANOVA, p<0.001) of BMSCs, however, the effect is inhibitory (Figure 2b). At Day 8, normalized ALP was significantly lower for all FGF-2 concentrations compared to the controls (Dunnett’s T3, p<0.05). At Day 15, normalized ALP activity was significantly lower for 2.5, 10, and 40 ng/ml (Tukey, p<0.05) compared to untreated controls. At Day 22, ALP activity for 2.5 ng/ml was significantly higher compared to 10 and 40 ng/ml (Dunnett’s T3, p<0.01).

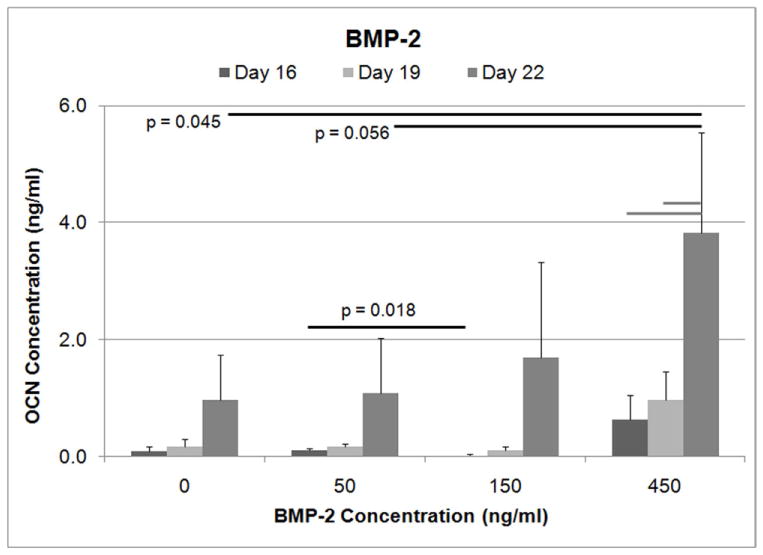

3.3 Effects of BMP-2 and FGF-2 on late stage osteogenic differentiation

In later stages of osteogenic differentiation, osteocalcin secretion (Figure 3) was higher for cells that were treated with higher concentrations of BMP-2 (ANOVA, p=0.036). At Day 22, BMSCs treated with a BMP-2 concentration of 450 ng/ml secreted significantly more osteocalcin than control cells (Tukey, p=0.045) and marginally more than cells treated with 50 ng/ml BMP-2 (Tukey, p=0.056). For 450 ng/ml of BMP-2, OCN secretion at Day 22 was significantly higher compared to OCN levels on Day 16, and Day 19 (p<0.05). In contrast, for the cells treated with FGF-2, osteocalcin levels were not significantly different controls (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Osteocalcin secretion levels determined by ELISA. For Day 22, the cells treated with 450 ng/ml of BMP-2 demonstrated significantly higher OCN levels compared to the untreated controls as determined by ANOVA. OCN level for the 450 ng/ml concentration of BMP-2 was also marginally higher compared to the 50 ng/ml BMP-2 treatment group. (Gray bars indicate p<0.05).

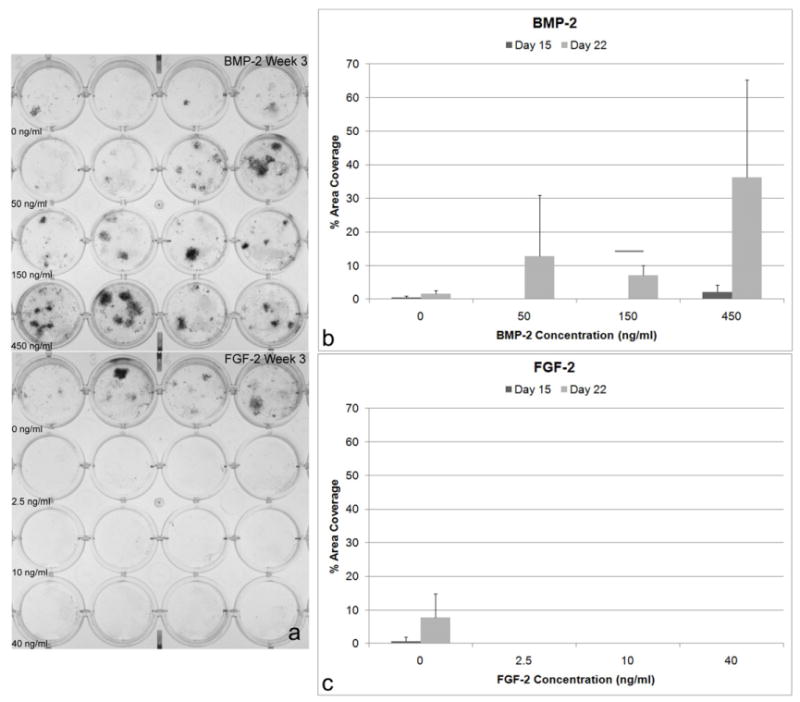

At Day 22, there was a trend towards higher mineral coverage (p < 0.065) when BMSCs were treated with BMP-2 compared to untreated controls (Figure 4). Adding FGF-2 at any concentration inhibited mineral deposition. The control cells demonstrated some mineral deposition, however, the difference with varying FGF-2 concentration was not statistically significant.

Figure 4.

Mineral secreted from BMSCs. A) von Kossa staining of BMSCs treated with BMP-2 at 0, 50, 150, and 450 ng/ml and BMSCs treated with FGF-2 at 0, 2.5, 10, 40 ng/ml. Mineral deposition (% of area covered) determined using von Kossa staining: B) At Day 22, there was a trend towards higher mineral coverage when BMSCs are treated with BMP-2 compared to untreated controls (ANOVA, p < 0.065). C) In contrast, treatment with FGF-2 in any concentration inhibits the deposition of mineral. Although this was not statistically significant, the control cells demonstrated mineral deposition, whereas FGF-2 treated cells did not.

3.4 Effects of BMP-2 and FGF-2 sequence on DNA content

The concentrations of FGF-2 and BMP-2 used in the sequential exposure experiments (2.5 and 300 ng/ml, respectively) were based on the results from the exposure of BMSCs to each growth factor individually. Since FGF-2 increased DNA content, but inhibited osteogenic differentiation, the minimum concentration of 2.5 ng/ml was chosen to increase the number of cells that can be osteogenically induced (Figure 1). For BMP-2, a concentration of 300 ng/ml was chosen due to cost limitations and the necessity for a concentration of BMP-2 that was higher than the 150 ng/ml threshold for a significant increase in differentiation (Figure 2). Due to the cell layers contracting for some of the treatment groups, the time points at which DNA, ALP, OCN, and mineral deposition were examined (8, 11, 13 d) differed from the times in the individual growth factor experiments.

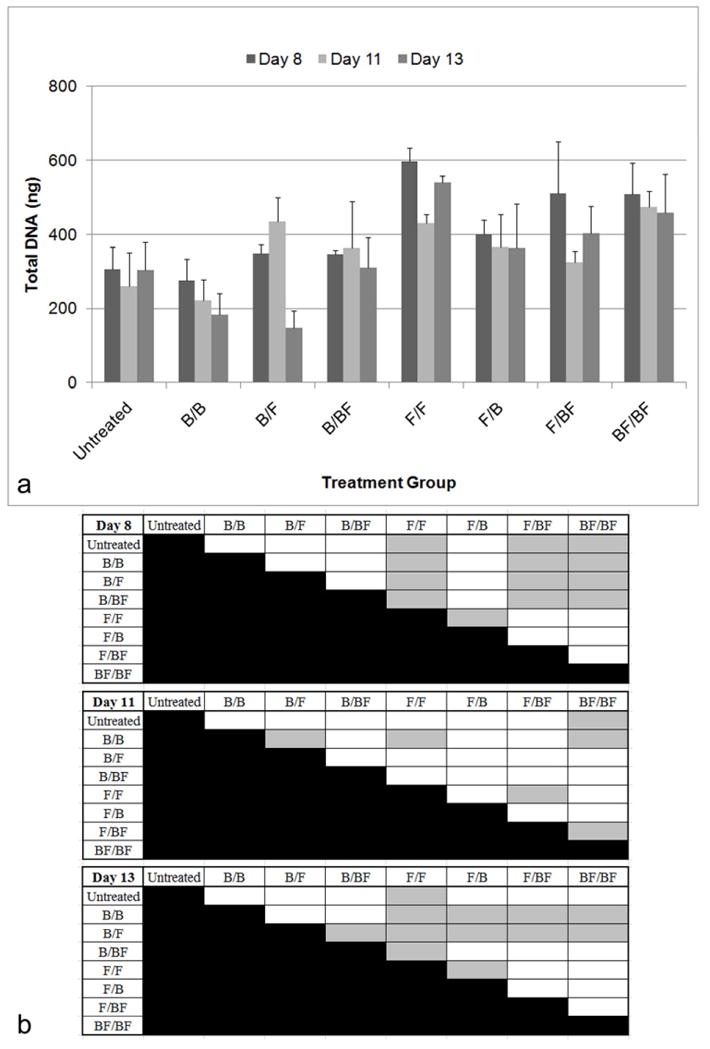

The duration of FGF-2 exposure significantly affected the total DNA content (Figure 5). At Day 8, groups that delivered FGF-2 first: FGF-2 alone (F/F), FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 and FGF-2 (F/BF), and both factors simultaneously (BF/BF) had significantly higher DNA levels compared to the untreated controls and the groups that delivered BMP-2 first (Tukey, p<0.05). At Day 11, BMP-2 followed by FGF-2 (B/F), FGF-2 alone (F/F), and both factors delivered simultaneously (BF/BF) had higher DNA content compared to groups that only delivered BMP-2 (Dunnett’s T3, p<0.05). At Day 13, the groups that delivered FGF-2 first: FGF-2 alone (F/F), FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 (F/B), FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 and FGF-2 (F/BF), and both factors simultaneously (BF/BF) had significantly higher DNA content compared to BMP-2 alone (B/B) and BMP-2 followed by FGF-2 (B/F), where BMP-2 is delivered first (Tukey, p<0.05). Groups that delivered FGF-2 the entire time period tended towards having higher DNA levels. Most groups that delivered FGF-2 second also trended towards having higher DNA levels.

Figure 5.

Total DNA quantified using Picogreen based on exposure of BMSCs to BMP-2 (300 ng/ml) and FGF-2 (2.5 ng/ml). The nomenclature for growth factor delivery, X/Y, is defined in Table 1. A) At Day 8, F/F, F/BF, and BF/BF have significantly higher DNA levels compared to untreated controls and the groups that delivered BMP-2 first (Tukey, p<0.05). At Day 11, B/F, F/F, and BF/BF had significantly higher levels of DNA compared to the group that only delivered BMP-2 (Dunnett’s T3, p<0.05). At Day 13, F/F, F/B, F/BF, and BF/BF had higher DNA content compared to B/B and B/F where BMP-2 is delivered first (Tukey, p<0.05). B) Table of statistical significances among the treatment groups. Gray boxes designate p<0.05.

3.5 Effects of BMP-2 and FGF-2 sequence on ALP activity

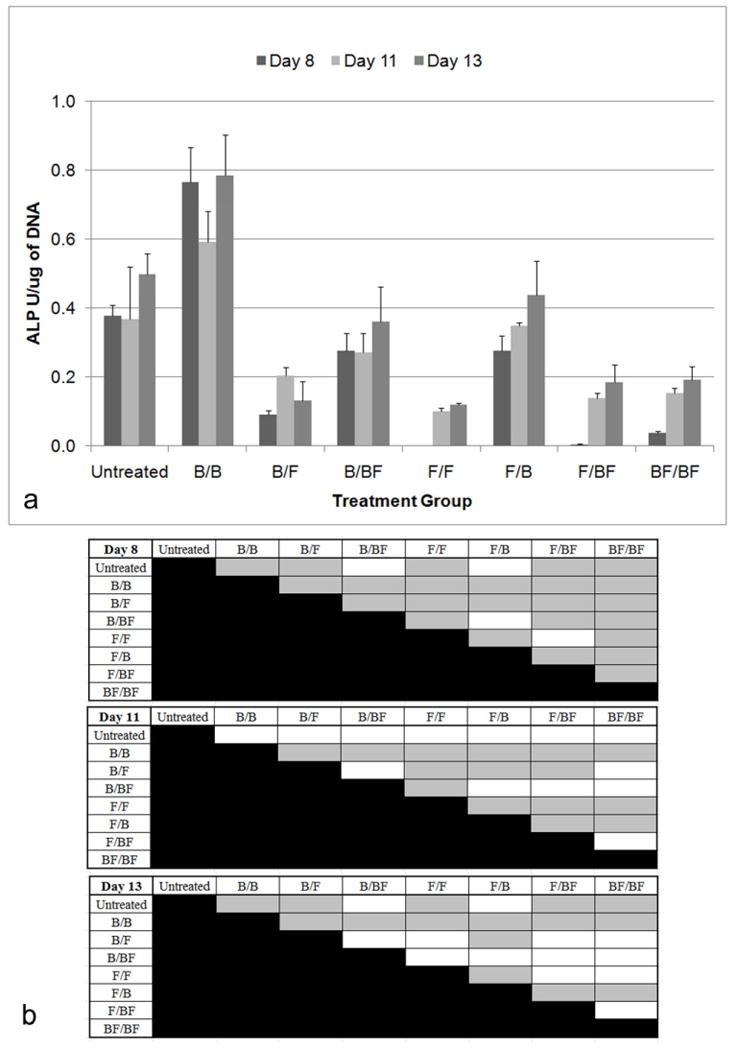

Delivering BMP-2 alone (B/B) led to the highest ALP levels (Figure 6). Taken in conjunction with relatively low DNA levels for the B/B group (Figure 5) suggests that a smaller population of cells had enhanced osteogenic activity. Delivering FGF-2 alone (F/F) also resulted in a low level of ALP expression. However, when both growth factors were delivered, the effects varied, depending on the sequence of delivery (ANOVA, p<0.001). At Day 8, ALP levels for FGF-2 alone (F/F) and FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 and FGF-2 (F/BF) were significantly lower compared to all other groups. The sequential delivery of BMP-2 and FGF-2 in either order (F/B and B/F) led to significantly higher ALP levels compared to delivering both factors simultaneously (BF/BF) (Dunnett’s T3, p<0.05). Delivery of FGF-2 first, then BMP-2 (F/B) resulted in higher ALP levels compared to delivery of BMP-2 first, followed by FGF-2 (B/F).

Figure 6.

Normalized ALP with respect to total DNA. The nomenclature for growth factor delivery, X/Y, is defined in Table 1. A) For Day 8, the ALP activity of B/B was significantly higher than all other groups (Dunnett’s T3, p<0.05). The ALP levels for F/F and F/BF were significantly lower compared to all other groups. Sequential delivery of FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 led to significantly higher ALP levels compared to delivering both factors simultaneously. Delivering FGF-2 first, and then BMP-2 resulted in higher ALP levels compared to delivering BMP-2 first, followed by FGF-2. Additionally delivering BMP-2 the entire time period also resulted in higher ALP levels compared to delivering FGF-2 the entire time period. Inclusion of FGF-2 resulted in significantly lower levels in all groups except B/BF and F/B. For Day 11, F/B still demonstrated higher ALP compared to all groups except the untreated cells and B/BF. For Day 13, F/B continued to demonstrate high ALP levels compared to all groups except the controls and B/BF. Untreated cells, B/B, and F/B had significantly higher ALP levels compared to BF/BF. B) Table of statistical significances among the treatment groups. Gray boxes designate p<0.05.

Inclusion of FGF-2 resulted in significantly lower levels of ALP in all groups except BMP-2 followed by BMP-2 and FGF-2 (B/BF) and FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 (F/B). Groups that were not exposed to FGF-2 for the entire 6 days had higher ALP levels compared to all of the other groups. At Day 11, FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 (F/B) still demonstrated higher ALP compared to all groups except the untreated cells and BMP-2 followed by BMP-2 and FGF-2 (B/BF) (Dunnett’s T3, p<0.05). At Day 13, FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 (F/B) continued to demonstrate high ALP levels compared to all groups except the controls and BMP-2 followed by BMP-2 and FGF-2 (B/BF) (Dunnett’s T3, p<0.05). Untreated cells, BMP-2 alone (B/B), and FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 (F/B) had significantly higher ALP levels compared to both factors simultaneously (BF/BF).

3.6 Effects of BMP-2 and FGF-2 sequence on late stage osteogenic differentiation

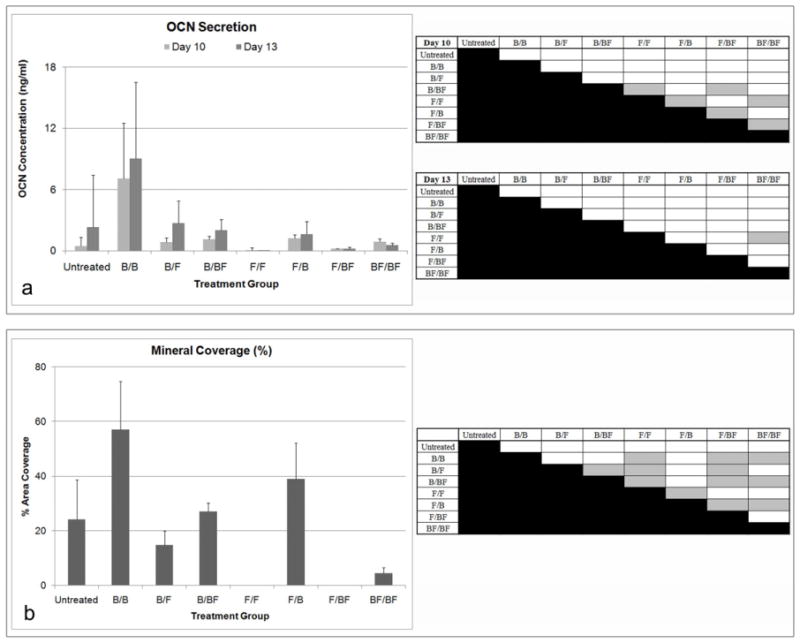

The different sequences of delivery also had a significant impact on OCN secretion (ANOVA, p<0.001) (Figure 7a). Delivery of FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 (F/B), BMP-2 followed by BMP-2 and FGF-2 (B/BF), and both factors simultaneously (BF/BF) led to significantly higher levels of OCN compared to FGF-2 alone (F/F) and FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 and FGF-2 (F/BF) (Dunnett’s T3, p<0.05). Although not statistically significant, delivering BMP-2 alone (B/B) resulted in the highest OCN levels, following a similar trend in ALP levels (Figure 6). Delivering BMP-2 the entire 6 days (B/BF) led to higher OCN levels compared to delivering FGF-2 during the entire time period (F/BF), which suggests that if the cells had not contracted early, the differences between the groups may have been more significant.

Figure 7.

A) OCN secretion of BMSCs in response to BMP-2 and FGF-2 administration and table of statistical significances among the treatment groups. Gray boxes designate p<0.05. The nomenclature for growth factor delivery, X/Y, is defined in Table 1. F/B, B/BF, and BF/BF had higher levels of OCN compared to F/F and F/BF (Dunnett’s T3, p<0.05). Delivering BMP-2 the entire time period when both growth factors are included led to higher OCN compared to delivering FGF-2 the entire time period. B) Mineral deposition (% of area covered) determined using von Kossa staining and table of statistical significances among the treatment groups. Gray boxes designate p<0.05. Delivering FGF-2 first followed by BMP-2 had higher mineral coverage compared to delivery both factor simultaneously. Groups that delivered FGF-2 the entire time period tended to have lower mineral coverage including the delivery of both growth factors at the same time (Dunnett’s T3, p<0.05).

Mineral deposition was also dependent on when the growth factors were administered (ANOVA, p<0.001) (Figure 7b). Delivering BMP-2 alone (B/B) resulted in higher mineral coverage compared to FGF-2 alone (F/F), FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 and FGF-2 (F/BF), and both factors delivered simultaneously (BF/BF). Groups that delivered FGF-2 the entire 6 days had lower mineral coverage, including the simultaneous delivery of FGF-2 and BMP-2 (BF/BF) (Dunnett’s T3, p<0.05). Delivering FGF-2 first followed by BMP-2 (F/B) had higher mineral coverage compared to the delivery of both factors simultaneously (BF/BF). Additionally, BMP-2 followed by BMP-2 and FGF-2 (B/BF) also had higher mineral coverage compared to simultaneous delivery, suggesting that the delivery of BMP-2 the entire 6 days can override the inhibitive effects of delivering FGF-2 to osteogenic activity.

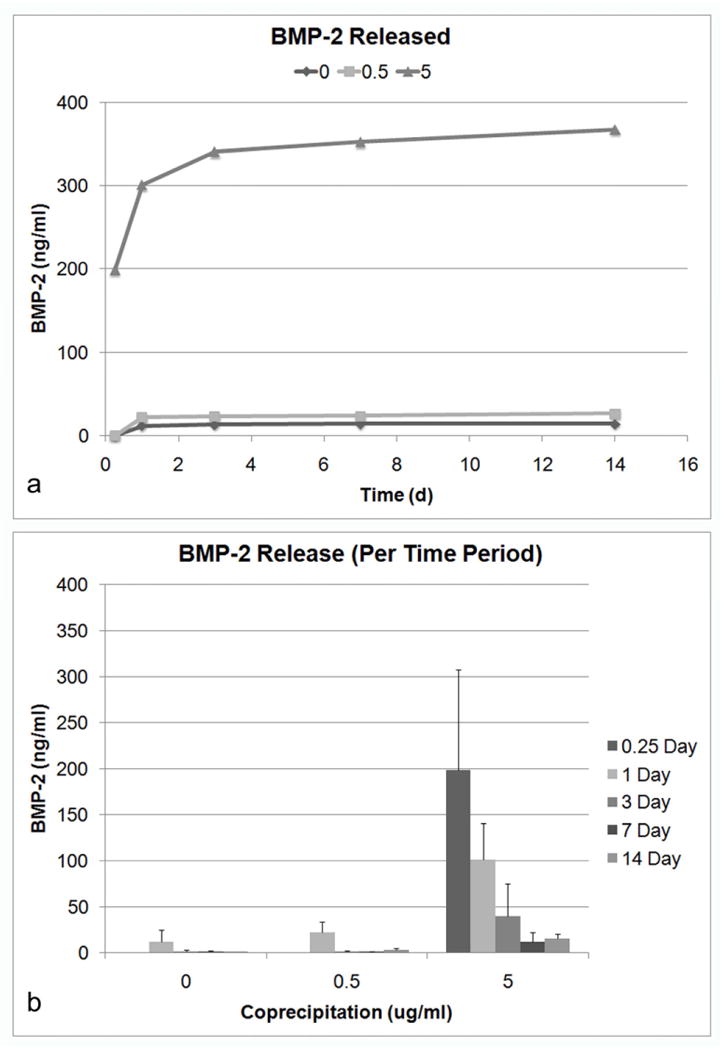

3.7 BMP-2 and FGF-2 release kinetics

Varying the concentration of BMP-2 used during coprecipitation had significant effects on the concentration of BMP-2 released (ANOVA repeated measures, p<0.001) (Figure 8). Adding 5 μg/ml of BMP-2 during coprecipitation resulted in significantly higher release compared to a concentration of 0.5 μg/ml, suggesting a higher BMP-2 incorporation into the apatite. The amount of BMP-2 released per time period was also significantly different (p<0.001) (Figure 8b). Over time, the amount of BMP-2 released decreased. There was also a significant interaction (p<0.001) between the time period of release and concentration, which suggests that BMP-2 release was significantly dependent on the concentration of BMP-2 used during coprecipitation.

Figure 8.

Release of BMP-2 is dependent on BMP-2 concentration in mSBF. A) Cumulative release of BMP-2 over the 14 day time period. B) Release of BMP-2 during each time period (6 h, 1, 3, 7, 14 d). Varying the BMP-2 concentration during coprecipitation had a significant effect on BMP-2 release (ANOVA repeated measures, p<0.001). There are also significant changes in the amount of BMP-2 released for each time period (p<0.001). Additionally, there is significant interaction (p<0.001) between time and concentration, further suggesting that BMP-2 release is significantly dependent on the concentration of BMP-2.

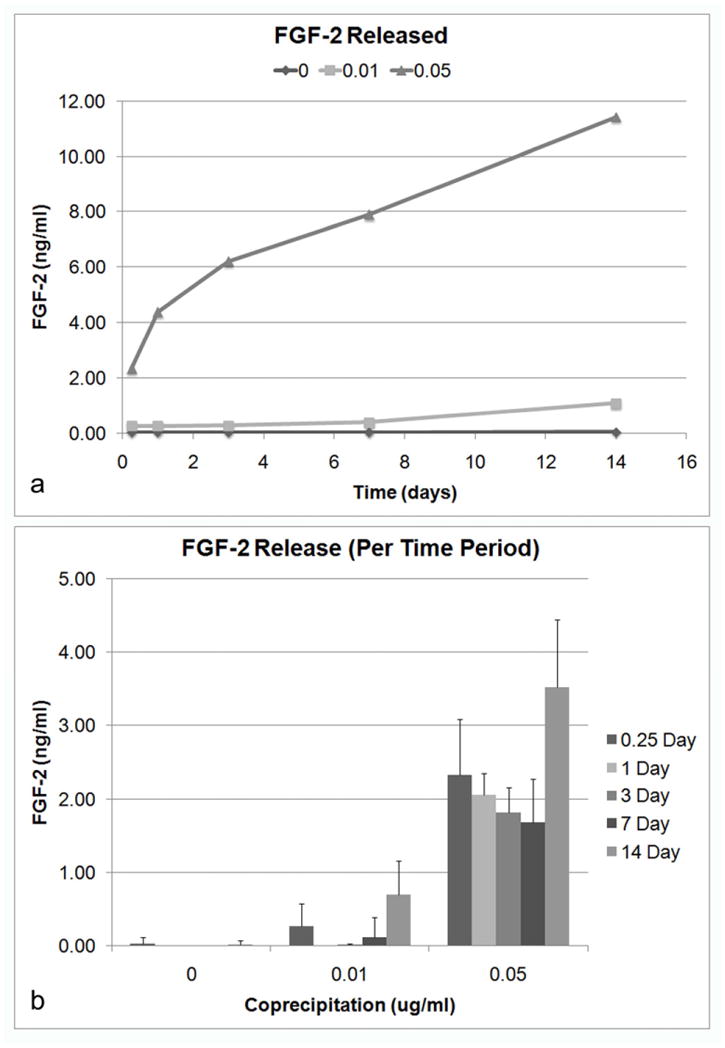

Varying the concentration of FGF-2 in mSBF also had significant effects on the concentration released (ANOVA repeated measures, p<0.001) (Figure 9). Adding 0.05 μg/ml of FGF-2 during coprecipitation resulted in significantly higher concentration released compared to a concentration of 0.01 μg/ml, suggesting a higher FGF-2 incorporation into the apatite. The amount of FGF-2 released per time period was also significantly different (p<0.001) (Figure 9b). For 0.05 μg/ml, the amount of FGF-2 released per time period did not change significantly with the exception of the last time period (7–14 d). There was also a significant interaction (p<0.001) between the time period of release and concentration, which suggests that FGF-2 release was also significantly dependent on the concentration of FGF-2 used during coprecipitation.

Figure 9.

Release of FGF-2 is dependent on FGF-2 concentration in mSBF. A) Cumulative release of FGF-2 over the 14 day time period. B) Release of FGF-2 during each time period (6 h, 1, 3, 7, 14 d). Varying the FGF-2 concentration during coprecipitation had a significant effect on FGF-2 release (ANOVA repeated measures, p<0.001). There are also significant changes in the amount of FGF-2 released for each time period (p<0.001). Additionally, there is significant interaction (p<0.001) between time and concentration, suggesting that FGF-2 release is significantly dependent on the concentration of FGF-2.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to provide design criteria for the development of a hybrid osteoconductive/osteoinductive delivery system in which the concentration and timing of release of multiple growth factors can be controlled. The aim was accomplished by 1) investigating the effects of varying concentration and sequence of BMP-2 and FGF-2 on the osteogenic differentiation of murine BMSCs and 2) incorporating BMP-2 and FGF-2 within apatite during coprecipitation and examining their release profiles. Analyzing the proliferative and differentiation responses of BMSCs to varying concentrations of BMP-2 and FGF-2 defined the concentrations of BMP-2 and FGF-2 to be included in mSBF during coprecipitation.

FGF-2, a well known mitogenic factor, increased DNA synthesis at all concentrations investigated, compared to the untreated controls (Figure 1b); however dose dependency was not demonstrated. FGF-2 had a significant negative impact on both early and late stage osteogenic differentiation, even at a low concentration of 2.5 ng/ml (Figures 2–4). FGF-2 plays a mitogenic role in endothelial cells, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, and osteoblasts [24, 25]. The effect that FGF-2 has on osteogenic differentiation in vivo is biphasic, where high doses (1 μg) result in an inhibitory effect on bone regeneration and low doses (10 ng and 100 ng) have a stimulatory effect [26]. In this study, a concentration of 2.5 ng/ml was determined to be most appropriate for the dual growth factor experiments in order to balance the proliferative properties of FGF-2 with its delaying effect on osteogenic differentiation.

Cells exposed to BMP-2 demonstrated a dose dependent increase in ALP, OCN and mineral deposition (Figures 2a, 3, 4b), which suggests that a higher concentration of BMP-2 may direct osteogenic differentiation even further. With a more mature osteoblastic cell line, this dose dependent increase is absent [6], however, the presence of more osteoprogenitor cells in a base population could lead to the dose dependency demonstrated in this study. Based on the concentrations examined, 450 ng/ml was most appropriate for further experimentation; however, due to cost limitations, 300 ng/ml was chosen for the sequential delivery experiments.

Using concentrations of 2.5 ng/ml for FGF-2 and 300 ng/ml for BMP-2, different growth factor sequences were administered to BMSCs (Table 1). The duration of delivery of each factor had a significant effect on BMSC growth and differentiation. Sequences that delivered BMP-2 for 6 days did not lead to a significant increase in DNA levels (Figure 5). Sequences that delivered FGF-2 for the entire 6 days led to higher DNA content, which implies that a more prolonged treatment of FGF-2 increases cell number better than treating the cells for a shorter period of time. However, the inclusion of FGF-2, even at a low concentration of 2.5 ng/ml, resulted in a significant decrease in osteogenic activity (Figures 6 – 7), even with a shorter time period of administration. The groups in which FGF-2 was administered for the entire 6 days had lower osteogenic activity compared to the groups that only delivered FGF-2 for 3 days. FGF-2- induced osteogenesis could be dependent on the stage of cellular differentiation, where late administration of FGF-2 can lead to matrix mineralization but no change in cell growth [27]. In vivo, nanogram levels of FGF-2 with BMP-2 can synergistically increase osteogenic differentiation, but on a microgram level serve to inhibit bone regeneration [28].

Differences in the delivery sequence also had a significant impact on the osteogenic activity of the BMSCs. Delivering FGF-2 first, followed by BMP-2 led to higher ALP levels and mineral deposition compared to simultaneous delivery of BMP-2 and FGF-2 (Figure 6, 7b). Bone chamber studies have also shown a high inhibition of bone formation due to a simultaneous delivery of BMP-2 and FGF-2 [29]. For OCN expression, FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 was not significantly different from simultaneous exposure. The comparable OCN levels suggests that due to the binding affinity of OCN for apatite [30], the OCN secreted from the cultured cells may have adsorbed to the mineralized nodules, especially in the case of FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 where mineral coverage was significantly higher (Figure 7).

The importance of sequential administration is also supported by our finding that FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 resulted in higher ALP activity and a trend toward higher mineral deposition than the reverse order of administration. Delivering BMP-2 the entire 6 days, and FGF-2 in the latter 3 days also resulted in relatively high osteogenic activity compared to the simultaneous delivery of both growth factors (Figure 6, 7). This is most likely due to the continuous presence of BMP-2, which is a potent inducer of osteoblastic differentiation. There are a few possible hypotheses for the increased efficacy of the sequential exposure of FGF-2 followed by BMP-2. First, FGF-2 may increase the efficacy of BMP-2 induction by stimulating precursor cells to enter the early stages of osteogenic differentiation [31–33]. Second, by treating cells with FGF-2 early, the population of osteoprogenitor cells that can be induced by BMP-2 to undergo the later stages of osteogenic differentiation is increased [10, 33]. Third, FGF-2 may selectively increase the number of cells that express BMP-2 receptors or increase the expression of a specific receptor, BMPR-1B, which would potentiate BMP-2 induction [10, 34]. Selective BMP-2 receptor dependency is a possible cause for ectopic bone formation induced by delivering low doses of FGF-2 with BMP-2 [34].

The second objective of this study was to incorporate FGF-2 and BMP-2 into the apatite coating utilizing coprecipitation and examine their release. In order to provide a design basis for the delivery system, the growth factor concentrations used for coprecipitation were varied. The concentration and sequence effects of BMP-2 and FGF-2 (Figures 1–7) can be used in conjunction with growth factor release kinetics (Figures 8, 9) to develop a delivery system that mimics the osteogenic response of BMSCs. FGF-2 and BMP-2 can be spatially localized within biomimetic apatite using coprecipitation to tailor the concentration and sequence of growth factor delivery [22]. For both FGF-2 and BMP-2, a higher growth factor concentration in bone-like mineral resulted in higher release. More BMP-2 was released in the earlier time periods, with decreases at subsequent times (Figure 8). While FGF-2 also demonstrated a “burst”, the release was more sustained over time (Figure 9). The differing release profiles suggest the affinity of the factors for apatite influenced their release. This interpretation is supported by data showing that increasing adsorption affinities of other biomolecules, such as antibacterial agents, to apatite surfaces results in decreased release rates [35]. Based on the release kinetics, BMP-2 may have a lower affinity to the bone-like mineral relative to FGF-2. BMP-2 has a pI of 8.2, while FGF-2 has a pI of 9.6 [36, 37]. Therefore, at the same pH, different charges may affect binding to apatite. Since this delivery system can be adapted for other growth factors, the isoelectric points of the growth factors would have to be considered in the design.

The composition of the mineral also plays a role in the design of this hybrid delivery system. One of the advantages of using a biomimetic approach is that the apatite can be altered by modifying the ionic concentrations of the salts used to precipitate the mineral onto the substrate. By altering the composition and concentration of SBF, material properties of bone-like mineral that influence cellular response can be controlled, including morphology, crystallinity, composition and dissolution [38]. For example, apatite formed from a supersaturated ionic solution is carbonated [39], but the amount of carbonate is controlled by SBF composition, and influences crystallinity, solubility [40] and therefore growth factor release kinetics.

The long term goal is to design an organic/inorganic delivery system that has the potential to deliver multiple biological factors to better mimic spatiotemporal gradients that cells are exposed to in vivo by controlling the release of biomolecules from within the apatite. By utilizing coprecipitation to control the spatial location of multiple growth factors, the sequential release of two factors can be manipulated to optimally differentiate BMSCs. Translating the delivery system from in vitro to in vivo requires additional considerations of blood flow, other extracellular matrix proteins and cells endogenous to the defect site, immune response, surrounding pH, and interactions with other signaling molecules. In addition to apatite dissolution, growth factor diffusion from bone-like mineral, and formation of apatite-growth factor complexes may also have significant roles in the in vivo environment, and thereby, have a significant effect on the release of the growth factors in a defect site.

5. Conclusion

To design a controllable delivery system for multiple growth factors, the sequence and concentration dependent effects of FGF-2 and BMP-2 and their respective release from the apatite coatings were examined. From the individual growth factor experiments, low concentrations of FGF-2 resulted in higher cell number while high concentrations of BMP-2 best enhanced osteogenic differentiation. The sequence of delivery of BMP-2 and FGF-2 also had a significant impact on osteogenic differentiation. The delivery of FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 or even the delivery of BMP-2 followed by the delivery of both BMP-2 and FGF-2 enhanced osteogenic differentiation compared to the simultaneous delivery of both factors. The release of BMP-2 and FGF-2 was significantly affected by the concentration used during coprecipitation. BMP-2 demonstrated a higher “burst” release compared to FGF-2. By integrating the results of the sequential delivery of BMP-2 and FGF-2 with data on the release of the growth factors from the mineralized substrates, an organic/inorganic delivery system based on coprecipitation can be designed to deliver multiple biological factors. This hybrid system would be able to better mimic the spatial and temporal gradients that cells are exposed to in vivo by controlling the release of biomolecules from within apatite.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by NIH DE 015411 (DHK), DE 13380 (DHK), and the Tissue Engineering at Michigan Grant T32 DE007057 (LNL). The authors would also like to thank Erin McNerny for her assistance with the extraction of murine bone marrow stromal cells.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tabata Y. Tissue regeneration based on growth factor release. Tissue Eng. 2003;9:S5–S15. doi: 10.1089/10763270360696941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peng H, Wright V, Usas A, Gearhart B, Shen HC, Cummins J, et al. Synergistic enhancement of bone formation and healing by stem cell-expressed VEGF and bone morphogenetic protein-4. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:751–759. doi: 10.1172/JCI15153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ripamonti U, Crooks J, Petit JC, Rueger DC. Periodontal tissue regeneration by combined applications of recombinant human osteogenic protein-1 and bone morphogenetic protein-2. A pilot study in Chacma baboons (Papio ursinus) Eur J Oral Sci. 2001;109:241–248. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2001.00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raiche AT, Puleo DA. In vitro effects of combined and sequential delivery of two bone growth factors. Biomaterials. 2004;25:677–685. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00564-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang WB, Carlsen B, Wulur I, Rudkin G, Ishida K, Wu B, et al. BMP-2 exerts differential effects on differentiation of rabbit bone marrow stromal cells grown in two-dimensional and three-dimensional systems and is required for in vitro bone formation in a PLGA scaffold. Exp Cell Res. 2004;299:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamaguchi A, Katagiri T, Ikeda T, Wozney JM, Rosen V, Wang EA, et al. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 stimulates osteoblastic maturation and inhibits myogenic differentiation invitro. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:681–687. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.3.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho TJ, Gerstenfeld LC, Einhorn TA. Differential temporal expression of members of the transforming growth factor beta superfamily during murine fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:513–520. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurley MM, Marie PJ, Florkiewicz RZ. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and FGF receptor families in bone. In: Bilezikian JP, Raisz LG, Rodan GA, editors. Principles of bone biology. San Diego: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 825–851. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canalis E, Centrella M, Mccarthy T. Effects of Basic Fibroblast Growth-Factor on Bone-Formation Invitro. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:1572–1577. doi: 10.1172/JCI113490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanada K, Dennis JE, Caplan AI. Stimulatory effects of basic fibroblast growth factor and bone morphogenetic protein-2 on osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1606–1614. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.10.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson TP, Peters MC, Ennett AB, Mooney DJ. Polymeric system for dual growth factor delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:1029–1034. doi: 10.1038/nbt1101-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sohier J, Vlugt TJH, Cabrol N, Van Blitterswijk C, de Groot K, Bezemer JM. Dual release of proteins from porous polymeric scaffolds. J Control Release. 2006;111:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simmons CA, Alsberg E, Hsiong S, Kim WJ, Mooney DJ. Dual growth factor delivery and controlled scaffold degradation enhance in vivo bone formation by transplanted bone marrow stromal cells. Bone. 2004;35:562–569. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hench LL. Bioceramics - from Concept to Clinic. J Am Ceram Soc. 1991;74:1487–1510. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy WL, Kohn DH, Mooney DJ. Growth of continuous bonelike mineral within porous poly(lactide-co-glycolide) scaffolds in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;50:50–58. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200004)50:1<50::aid-jbm8>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohn DH, Shin K, Hong SI, Jayasuriya AC, Leonova EV, Rossello RA, et al. Self-assembled mineral scaffolds as model systems for biomineralization and tissue engineering. In: Landis WJ, Sodek J, editors. Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on the Chemistry and Biology of Mineralized Tissues. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kong HJ, Liu JD, Riddle K, Matsumoto T, Leach K, Mooney DJ. Non-viral gene delivery regulated by stiffness of cell adhesion substrates. Nat Mater. 2005;4:460–464. doi: 10.1038/nmat1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeung T, Georges PC, Flanagan LA, Marg B, Ortiz M, Funaki M, et al. Effects of substrate stiffness on cell morphology, cytoskeletal structure, and adhesion. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2005;60:24–34. doi: 10.1002/cm.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen HB, de Wijn JR, van Blitterswijk CA, de Groot K. Incorporation of bovine serum albumin in calcium phosphate coating on titanium. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;46:245–252. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199908)46:2<245::aid-jbm14>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen HB, Wolke JG, de Wijn JR, Liu Q, Cui FZ, de Groot K. Fast precipitation of calcium phosphate layers on titanium induced by simple chemical treatments. Biomaterials. 1997;18:1471–1478. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)82297-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azevedo HS, Leonor IB, Alves CM, Reis RL. Incorporation of proteins and enzymes at different stages of the preparation of calcium phosphate coatings on a degradable substrate by a biomimetic methodology. Mat Sci Eng C-Bio S. 2005;25:169–179. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luong LN, Hong SI, Patel RJ, Outslay ME, Kohn DH. Spatial control of protein within biomimetically nucleated mineral. Biomaterials. 2006;27:1175–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dobson KR, Reading L, Haberey M, Marine X, Scutt A. Centrifugal isolation of bone marrow from bone: an improved method for the recovery and quantitation of bone marrow osteoprogenitor cells from rat tibiae and femurae. Calcif Tissue Int. 1999;65:411–413. doi: 10.1007/s002239900723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berrada S, Lefebvre F, Harmand M. The effect of recombinant human basic fibroblast growth-factor rhFGF-2 on human osteoblast in growth and phenotype expression. In vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1995;31:698–702. doi: 10.1007/BF02634091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slavin J. Fibroblast growth factors: at the heart of angiogenesis. Cell Biol Int. 1995;19:431–444. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1995.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zellin G, Linde A. Effects of recombinant human fibroblast growth factor-2 on osteogenic cell populations during orthopic osteogenesis in vivo. Bone. 2000;26:161–168. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Debiais F, Hott M, Graulet AM, Marie PJ. The effects of fibroblast growth factor-2 on human neonatal calvaria osteoblastic cells are differentiation stage specific. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:645–654. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.4.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujimura K, Bessho K, Okubo Y, Kusumoto K, Segami N, Iizuka T. The effect of fibroblast growth factor-2 on the osteoinductive activity of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in rat muscle. Arch Oral Biol. 2002;47:577–584. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(02)00046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vonau RL, Bostrom MPG, Aspenberg P, Sams AE. Combination of growth factors inhibits bone ingrowth in the bone harvest chamber. Clin Orthop. 2001:243–251. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200105000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hauschka PV, Wians FH. Osteocalcin-hydroxyapatite interaction in the extracellular organic matrix of bone. Anat Rec. 1989;224:180. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092240208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fakhry A, Ratisoontorn C, Vedhachalam C, Salhab I, Koyama E, Leboy P, et al. Effects of FGF-2/-9 in calvarial bone cell cultures: differentiation stage-dependent mitogenic effect, inverse regulation of BMP-2 and noggin, and enhancement of osteogenic potential. Bone. 2005;36:254–266. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ono I, Tateshita T, Takita H, Kuboki Y. Promotion of the osteogenetic activity of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein by basic fibroblast growth factor. J Craniofac Surg. 1996;7:418–425. doi: 10.1097/00001665-199611000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maegawa N, Kawamura K, Hirose M, Yajima H, Takakura Y, Ohgushi H. Enhancement of osteoblastic differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells cultured by selective combination of bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) and fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2007;1:306–313. doi: 10.1002/term.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakamura Y, Tensho K, Nakaya H, Nawata M, Okabe T, Wakitani S. Low dose fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) enhances bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2)-induced ectopic bone formation in mice. Bone. 2005;36:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oyane A, Yokoyama Y, Uchida M, Ito A. The formation of an antibacterial agent-apatite composite coating on a polymer surface using a metastable calcium phosphate solution. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3295–3303. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nugent MA, Iozzo RV. Fibroblast growth factor-2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2000;32:115–120. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirsch T, Nickel J, Sebald W. Isolation of recombinant BMP receptor IA ectodomain and its 2:1 complex with BMP-2. FEBS Lett. 2000;468:215–219. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01214-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin K, Jayasuriya AC, Kohn DH. Effect of ionic activity products on the structure and composition of mineral self assembled on three-dimensional poly(lactide-co-glycolide) scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2007;83A:1076–1086. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphy WL, Mooney DJ. Bioinspired growth of crystalline carbonate apatite on biodegradable polymer substrata. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1910–1917. doi: 10.1021/ja012433n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang RK, Henneman ZJ, Nancollas GH. Constant composition kinetics study of carbonated apatite dissolution. J Cryst Growth. 2003;249:614–624. [Google Scholar]