Abstract

Protein interactions are at the basis of all processes in living organisms. In particular, regulatory proteins do not act alone but participate in multifaceted sets of interactions that are organized into complex networks. In herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) infected cells, viral proteins interact with cellular proteins and with other viral proteins to form the protein complexes required for virus production, including transcription complexes, replication complexes and virion assembly complexes. While a number of methods have been developed to investigate protein-protein interactions such as coimmunoprecipitation, GST-binding assays and yeast 2-hybrid analyses, these approaches require removal of the proteins from the cellular environment and do not provide information on the spatial localization of the protein-protein interaction in living cells. The fluorescence based approach Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) allows direct visualization of the subcellular localization of the protein complex in living cells. In BiFC, two halves of a fluorescent protein are fused to each of two interacting proteins of interest, resulting in non fluorescent fusion proteins. Interaction of the protein partners tethers the fused fluorescent fragments in close proximity, which facilitates their association and restoration of fluorescence. Two limitations of BiFC are that there is a delay between the time that the interacting proteins associate and fluorescence complex formation and thus complex formation cannot be measured in real-time, and fluorescence complex formation is irreversible in vivo. Despite these limitations, BiFC is a powerful and sensitive approach that can be performed using standard molecular biology and cell culture protocols and a fluorescence microscope.

Keywords: Bi-molecular Fluorescence Complementation, protein interaction, herpesviruses, ICP27

1. Introduction

Fluorescence approaches for the direct visualization of protein-protein interactions in cells can reveal not only that two proteins interact in vivo but also the subcellular localization of the interaction. The most commonly used approach is colocalization in which cells are fixed and stained with antibodies that are directly or indirectly tagged with a fluorophore. A disadvantage of fluorescence colocalization is that there can be high background fluorescence if the proteins are localized throughout a subcellular compartment making it difficult to interpret results. A further disadvantage is that two proteins may colocalize in the same region but may not actually interact with each other. Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) is another method for analyzing protein-protein interactions in living cells [1–3]. In FRET a donor fluorophore and an acceptor fluorophore are fused to the interacting proteins of interest. FRET can measure the distance between the donor and acceptor because upon excitation of the donor fluorophore, a fraction of the energy is transferred to the acceptor. The efficiency of energy transfer or FRET efficiency is used as a measure of the interaction of the two proteins. Typically, FRET efficiency is limited to distances between 1 to 10 nm. FRET assays require a fluorescence microscope that is specifically adapted to perform FRET and rather complex data processing is required to determine FRET efficiency. In contrast, Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) is relatively simple to perform and this approach allows the direct visualization of protein interactions in living cells [4–8]. BiFC is based upon protein complementation approaches that demonstrated that some protein fragments could associate more readily in vivo when these fragments were fused to proteins that interact with each other. These protein fragments include ubiquitin [9], beta-lactamase [10] and dihydrofolate reductase [11]. Complementation between fragments of green fluorescent protein (GFP) was first shown in bacteria when these fragments were fused to artificial interacting peptides [12]. Since that first demonstration, Kerppola and coworkers have pioneered the use of BiFC in mammalian cells using variants of YFP [4–8].

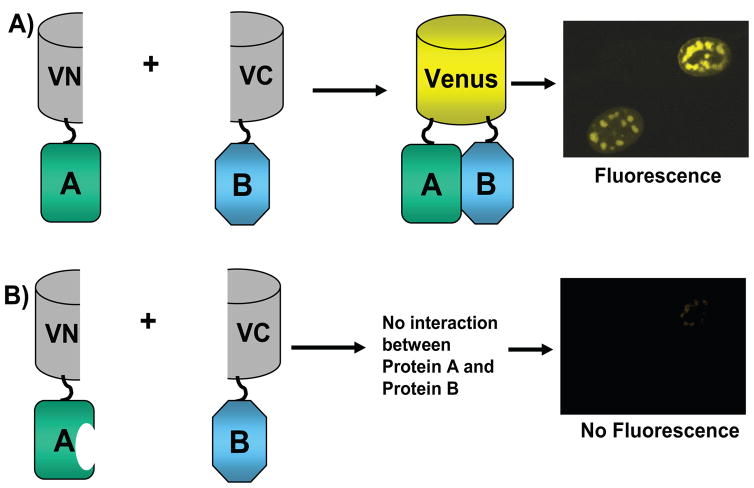

In BiFC, two halves of a fluorescent protein are fused to proteins or protein domains that interact. Upon the interaction of the protein partners, the tethered fluorescent fragments associate and after maturation of the complex, fluorescence occurs (Figure 1). The time and conditions under which fluorophore formation occurs varies depending on the fluorophore. YFP was used initially but fluorophore maturation is sensitive to higher temperatures and thus incubation at 30°C is required and it takes an hour or more for fluorescence to occur [13]. In contrast, a modified version of YFP termed Venus can undergo fluorophore maturation in around 10 minutes at 37°C [14]. Furthermore, BiFC complex formation is dependent upon protein folding because the fluorescent protein fragments must fold upon association to fluoresce. Association of the fluorescent protein fragments produces new interaction interfaces in the β barrel of the fluorescent protein and each interface has between six and nine hydrogen bonds. The hydrogen bonding networks are very stable [8] and thus dissociation of the complexes once formed does not occur in vitro and is not likely to occur in vivo [13,15]. Although BiFC generally has very low background, very high expression of the non fluorescent fusion proteins can result in BiFC between proteins that do not interact in vivo [8]. That is, overexpression of the fusion proteins can lead to the association of the tethered fluorescent protein fragments because of high local concentrations of the fusion proteins. This can be avoided if plasmid DNA concentrations in transfections are kept low. In our studies with HSV-1 regulatory protein ICP27, the ICP27-Venus fusion constructs were placed under the control of the native ICP27 promoter, which is not expressed to high levels in transfected cells [16,17]. Twenty four hours after transfection, cells were infected with the ICP27 null mutant virus 27-LacZ. Viral tegument protein VP16 activates the ICP27 promoter so that expression of the ICP27-Venus fusion protein is commensurate with immediate early protein expression in the context of HSV-1 infection. We found that infecting the transfected cells with wild type HSV-1 KOS did not interfere with BiFC, indicating that the presence of untagged ICP27 did not prevent BiFC for N-C-Venus-ICP27 [16]. In studies of HSV-1 glycoprotein interactions and complex formation for viral entry, GFP-, YFP- and Venus-tagged glycoprotein constructs were under the control of the CMV IE enhancer, however background fluorescence levels were low in these studies [18,19]. An important control that must be performed in BiFC experiments is the use of a mutant fusion protein in which the region required for interaction of the protein partners has been altered such that interaction cannot occur. BiFC should not occur (Figure 1B). If fluorescence is seen, it is background fluorescence and indicates that the florescent fragments are associating in the absence of protein interaction. Alternatively, if a drug or compound is known to disrupt the interaction between the proteins of interest, it may be possible to use the drug in place of the aforementioned control. However, careful consideration must be given to the timing of drug addition because of the irreversibility of BiFC. If it is not possible to disrupt the interaction between the two proteins of interest, at a minimum, co-expression of each of the fusion proteins with the complementary half of the fluorescent protein alone, should result in no fluorescence restoration. It is also very important to point out that standardization of image capture conditions is important. The settings on the microscope must be the same for all samples that are being viewed and the images must be captured at the same settings. Otherwise, it is possible that weak signals could be amplified by adjusting the brightness leading to false positive results.

Figure 1.

Illustration of BiFC. A) The N-terminal half of Venus (amino acids 1–154) was fused to Protein A and the C-terminal half of Venus (155 to 238) was fused to Protein B. Upon interaction of Protein A and Protein B, Venus fragments associate and refold and fluorescence occurs. B) Protein A has a deletion in the region that interacts with Protein B and therefore, Protein A cannot interact with Protein B, the two halves of Venus do not come into contact and there is no fluorescence.

It is also important to perform western blot analysis on lysates of transfected cells in each BiFC experiment to determine if both fusion proteins are expressed equivalently. Over-expression of one of the fusion proteins can lead to background fluorescence whereas poor expression of one of the fusion proteins can lead to a false negative BiFC result. Another important control is to determine the subcellular localization of each fusion protein by performing immunofluorescent staining with antibodies specific for each fusion protein. This will also determine if the fusion of the fluorescent fragment alters the sub cellular localization of the proteins of interest. This can be done by fixing the cells and performing indirect immunofluorescence with antibodies to each of the fused proteins. If antibodies to each protein of interest are not available, each protein can be tagged with an epitope tag. For example, a Flag-tag can be fused to protein A and an HA-tag can be fused to protein B. It is possible to view fluorescence of YFP or Venus in fixed cells and if a microscope is used that has a three channel filter set or multi laser channels, it is possible to view fluorescence of YFP and the fluorescence of each tagged protein at the same time. If this cannot be done on the microscope available, cells can be fixed on parallel coverslips and one set can be viewed for YFP fluorescence and one set viewed for the expression of each tagged protein by indirect fluorescence of the tagged proteins. This will determine that the proteins to which the YFP or Venus halves are fused are expressed in the same compartment in the same cell.

2. BiFC Protocol

2.1 Selection of BiFC fluorophores

A number of fluorophores have been described that work well in BiFC assays [13,15]. YFP N-terminal fragment 1–154 and C-terminal fragment 155–238 produce bright fluorescence when fused to interacting proteins and have low background when fused to non-interacting proteins. As mentioned above, a pre-incubation at 30°C is required and it takes at least an hour to visualize fluorescence. Fragments of YFP truncated at amino acid 173 producing YFP-N-1-172 and YFP-C-173-238 have also been used and work well in BiFC assays and tend to emit brighter fluorescence. [20]. Venus is a variant of YFP that has a substitution of phenylalanine with leucine at residue 46, which increases the oxidation of the fluorophore at 37°C [14]. Venus fluorescence is brighter than YFP but this can result in higher background if the fusion proteins are expressed at high levels. Recently, a substitution mutation from isoleucine to leucine at amino acid 152 within the N-terminal fragment of Venus was found to specifically reduce self-assembly and decrease background fluorescence, which further optimizes Venus-based BiFC [21]. Fragments of homologous fluorescent proteins such as Citrine and Cerulean have also been developed [13,15,22]. Plasmid vectors for BiFC including Venus and YFP versions are available from Addgene at: http://www.addgene.org/pgvec1?f=c&cmd=showcol&colid=684

2.2 Fusion of the fluorescent fragments to the proteins of interest

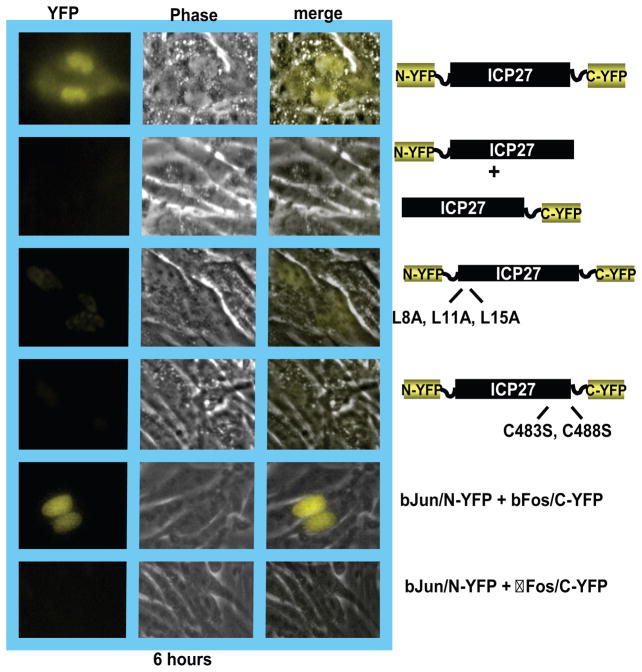

The N-terminal and C-terminal protein fragments can be fused to either the N- or C-terminus of a protein partner. The site chosen for fusion will have to be determined empirically if it is not known beforehand how the fusion of a peptide to the protein of interest will affect its activity, interactions and localization. In our studies on ICP27, we suspected that ICP27 may undergo a head-to-tail intramolecular interaction because several cellular proteins with which it interacts require that both the N- and C-termini be intact for interaction to occur. Therefore we fused the N-terminus of YFP or Venus to the N-terminus of ICP27 and the C-terminus of YFP or Venus to the C-terminus of ICP27 (Figure 2). To determine if intermolecular interaction could also occur through ICP27 dimerization, we fused the N-terminal half of YFP or Venus to the N-terminus of ICP27 in one construct and the C-terminus of YFP or Venus to the C-terminus of ICP27 in a different construct. Transfection of RSF cells with the dually tagged construct and cotransfection of RSF cells with each singly tagged construct was followed by infection with 27-LacZ virus twenty four hours later. At different times after infection, BiFC was observed using a LSM 510 confocal microscope. As shown in Figure 2, YFP fluorescence was seen with N-YFP-ICP27-C-YFP but not with N-YFP-ICP27 and ICP27-C-YFP, indicating that an intramolecular head-to-tail interaction had occurred but not an intermolecular interaction. To insure that the intramolecular interaction was not driven by the YFP fragments in N-YFP-ICP27-C-YFP ICP27, point mutations were introduced into the N- and C-terminal regions of ICP27. Leucine residues in the N-terminus of ICP27 were substituted with alanine and cysteine residues in the C-terminus were substituted with serine. In both cases fluorescence was not observed (Figure 2) indicating that an intramolecular interaction had not occurred. This confirmed that the interaction was driven by the N-and C-terminal interaction of ICP27 and not by the fused YFP fragments. We have reported similar results using Venus fragments [16].

Figure 2.

BiFC analysis shows that ICP27 undergoes a head-to-tail intramolecular interaction. RSF cells were transfected with plasmid DNA from ICP27-YFP fusion constructs N-YFP/ICP27/C-YFP, N-YFP/ICP27 + ICP27/C-YFP, N-YFP/ICP27 (L8A, L11A, L15A)/C-YFP and N-YFP/ICP27 (C483S, C488S)/C-YFP as indicated. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were infected with 27-LacZ at an MOI of 10. YFP fluorescence was visualized directly at 6 h after infection after incubation of the cells at 30°C for 2 hours. The positive control was bJun/N-YFP + bFos/C-YFP [4] and the negative control had a deletion in the interaction region of bFOS.

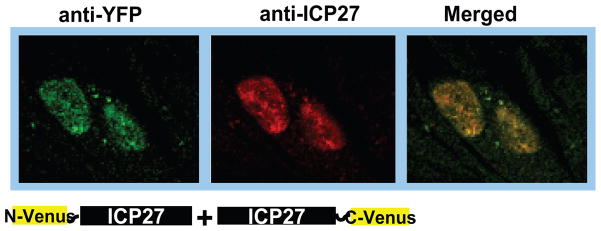

It is also important to verify that the fusion proteins are expressed at similar levels to rule out the possibility that low expression of one of the proteins is responsible for a negative BiFC result. A duplicate set of transfected cells should be lysed at the time that the BiFC assay is performed and these lysates should subsequently be subjected to western blot analysis. In addition, immunofluorescent staining should be performed to ascertain that the fusion proteins are similarly localized in the cell. Colocalization of N-Venus-ICP27 and ICP27-C-Venus is seen in Figure 3 as revealed by double staining with anti-YFP antibody, which recognizes an epitope in N-Venus, and anti-ICP27 antibody P1119, which recognizes an epitope that spans amino acids 1–9 of ICP27. This epitope is masked by the fusion of N-Venus such that P1119 will not bind to N-Venus-ICP27. The YFP antibody recognizes an epitope in the N-terminus of Venus and it will not bind to C-Venus. Thus, anti-ICP27 antibody recognizes ICP27-C-Venus and anti-YFP antibody recognizes N-Venus-ICP27. It is clear from Figure 3 that N-Venus-ICP27 and C-Venus-ICP27 are colocalized in the nuclei of co-transfected cells that were infected with 27-LacZ for 6 h.

Figure 3.

N-Venus/ICP27 and ICP27/C-Venus colocalize in transfected cells. RSF cells were transfected with N-Venus/ICP27 and ICP27/C-Venus DNA and 24 hours after transfection, cells were infected with 27-LacZ virus. Cells were fixed at 6 hours after infection and immunofluorescent staining was performed using anti-YFP antibody and anti-ICP27 antibody.

In investigating the interaction of ICP27 with the cellular proteins TAP/NXF1, an mRNA export receptor and Hsc70, a chaperone protein, which we previously showed interact with ICP27 [23,24], we tagged the N-terminus of TAP/NXF1 with N-Venus and the N-terminus of Hsc70 with N-Venus. ICP27 was tagged at the C-terminus with C-Venus [17]. BiFC was observed between ICP27 and TAP/NXF1 and between ICP27 and Hsc70 [17]. Furthermore, direct visualization of BiFC allowed us to observe ICP27 and TAP/NXF1 move to the cytoplasm at later times after infection as well as the movement of Hsc70 and ICP27 to nuclear foci or VICE domains [17] as we previously showed occurs in HSV-1 infected cells [23,24]. Both interactions were eliminated in the ICP27 cysteine to serine substitution mutant. Thus, BiFC is a powerful approach to visualize protein-protein interactions in living cells as well as to follow the subcellular localization of those interactions.

2.3 Plasmid construction

As described above, it is necessary to determine where the protein of interest should be tagged, either at the N-terminus or the C-terminus. When cloning the N- and C-terminal halves of Venus or other fluorophore, it is important to connect the fluorophore to the protein of interest by a flexible linker peptide. This is done to prevent changing the conformation of the protein of interest and to allow the fluorescent protein fragment to refold upon association with the other fragment. In our studies, we used peptides encoding RSIAT to attach the N-terminal half of the fluorescent protein and RPACKIPNDLKQKVMNH to attach the C-terminal half of the fluorescent protein, which were designed by Hu et al. [4]. These linkers have been used extensively with proteins that are structurally dissimilar. Other linkers have also been used successfully [20].

2.4 BiFC analysis-detailed protocol

This protocol has been optimized for 35 mm dishes.

Day 1

For live cell imaging, seed cells (we have used HeLa cells, Rabbit Skin Fibroblast (RSF) cells and Vero cells) on 35 mm glass bottom dishes (Matek) so monolayers are approximately 80–90% confluent on the day of transfection. If transfecting plasmid constructs followed by infection with HSV-1 the next day, prepare enough dishes for 4, 6, and 8 hour time points for each condition: positive control, negative control and experimental conditions. Prepare a control dish for counting cells in order to determine the amount of virus needed per dish -do not use glass bottom dishes for counting. If transfecting constructs without a subsequent infection, the cells will be viewed at 24 h after transfection and enough dishes should be prepared to observe later times if necessary as well as for the controls as described above.

Day 2

Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection/Co-transfection

Co-transfect cells with 2 μg each of plasmid DNA expressing the experimental BiFC fusion proteins. Also, co-transfect cells with control plasmids expressing experimental BiFC fusions that have a deletion or substitution mutation in the domains of interaction to show that BiFC does not occur when the two proteins can no longer interact. Co-transfect cells with 2 μg of each plasmid DNA used as a positive control and co-transfect 2 μg each of plasmid DNA being used as the negative control. Similarly, co-transfect cells with 2 μg of each plasmid DNA from the N-Venus and C-Venus fusions to be analyzed in the BiFC assay.

Dilute Lipofectamine 2000. For each co-transfection, combine 10 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 in 240 μl of Optimem. Incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes.

Dilute DNA. Combine 2 μg of each plasmid DNA with Optimem in a total volume of 250 μl. For co-transfection, total DNA will be 4 μg.

Combine diluted DNA (250 μl) and diluted Lipofectamine 2000 (250 μl) and allow DNA/Lipofectamine 2000 complex formation by incubating at room temperature for 20 minutes. Total volume will be 500 μl.

Wash cells 2X with Optimem and add 1.5 ml of Optimem to cells.

Add complexes (500 μl) to cells and incubate at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 5 hours.

Aspirate complexes and add 2 ml of growth media.

Incubate at 37°C with 5% CO2 overnight.

Day 3 (If infecting with virus)

Infection with HSV-1

We induce expression of the ICP27 fusion proteins by infecting cells with 27-LacZ virus.

Count cells on the control non-transfected dish using a hemocytometer.

- Calculate the amount of virus needed per dish based on the cell count, titer, and using a multiplicity of infection (moi) of ten with the following equation:

Wash cells 2X with PBS and add 500 μl of PBS + MgCl2 to cells. Add virus and gently mix. Incubate at 37°C with 5% CO2. Incubate for 45 minutes to allow adsorption.

Aspirate virus from cells and add 2 ml of growth media.

Day 3- viewing the cells for BiFC

For cells infected with virus, begin viewing cells for Venus fluorescence at 4 hours post-infection. The positive control should have strong Venus fluorescence at 4 hours post-infection and the negative control should show no Venus Fluorescence. If Venus fluorescence is not seen at 4 hours post-infection, continue to view cells at 6 and 8 hours post-infection for fluorescence.

For cells that are not infected after transfection, begin viewing the cells at 24 hours after transfection. If fluorescence is not seen, view again at later time points.

Take fluorescent images using either a confocal (514 nm laser line) or epifluorescent (YFP filter) microscope. Phase images should be taken as well to view the entire field. The phase and YFP fluorescent images should be merged to be able to count the number of fluorescent cells in the field. Several fields should be viewed and the number of positive cells counted in each field to obtain quantitative results. Large field images should be taken at 20X and higher magnification images should be taken at either at 100X or 63X for more detailed information on fluorescence localization. Fluorescence can also be quantified using imaging software programs such as ImageJ, which is available from NIH at: (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/

The protocol for using ImageJ in BiFC analyses has been described by Wong and O’Bryan [15].

2.5 Western Blot analysis

Cells must be harvested for protein to perform western blot analysis after each time point analyzed for BiFC.

On ice, wash cells 2X with ice cold PBS.

Scrape cells in 100 μL 2X ESS [16]and store at −80°C.

Separate 50 μl of the protein sample on a 10% polyacrylamide gel by SDS PAGE.

Transfer to nitrocellulose overnight.

Block membranes with 5% non-fat powder milk, if using the GFP antibody.

Perform western blotting using antibodies against Venus (Clontech GFP monoclonal mouse antibody – Cat. No. 632375) and an antibody against your protein of interest. Santa Cruz Biotechnology has commercially available antibodies, which are directed at the N-terminal and C-terminal regions of fluorescent proteins. Note several vectors that contain Venus protein fragments or other fluorophores also have tags such as a Flag epitope tag or an HA epitope tag. These should be considered if you do not have antibody available for your protein of interest. It is important to determine the intracellular localization of the fusion proteins, especially if BiFC is not observed.

2.6 Immunofluorescence staining

A duplicate set of cells should be fixed at the time that BiFC is viewed. We fix cells using 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 minutes.

Before staining, permeabilize cells in PBS containing 0.5% NP-40 for 5 minutes.

Rinse coverslips three times in PBS containing 1% newborn calf serum. In general, coverslips should be rinsed three times in PBS containing 1% newborn calf serum before the addition of each antibody or reagent.

Treat the cells with 1:100 dilution of donkey serum for 30 min to block nonspecific interactions. The type of serum used will be determined by the animal in which your secondary antibody was raised.

Rinse cells as above and add with the primary antibody. The dilutions will vary depending on the antibody and must be empirically determined.

After incubation with the primary antibody, proceed with the secondary antibody, according to standard immunofluorescence protocols.

2.7 Trouble Shooting

If BiFC is observed in the negative control, and the mutations that were introduced do prevent the interaction of the proteins of interest, it is likely that the BiFC fused proteins are expressed at too high levels in the cells. Very high local concentrations of the fusion proteins can lead to the association of the fluorophore fragments even if the tethered proteins do not interact, leading to high background levels. Reduce the amount of DNA for the plasmid constructs in the transfections or choose weaker promoters for the constructs to reduce fusion protein levels or switch to YFP if using Venus. YFP must be incubated at 30°C for at least an hour to observe fluorescence and this results in much lower background fluorescence [25].

If BiFC is observed in the positive control but not with the fusion proteins, there are several possible explanations. The position of the fluorophore tag on one or both of the proteins of interest may be interfering with the interaction by altering protein conformation or masking the region of interaction. In this case, move the tag to the N-terminus if it was originally on the C-terminus and visa versa.

If BiFC is not observed with the fusion proteins and western blot analysis indicates that one protein is expressed at higher levels than the other fusion protein, take steps to increase the expression of the poorly expressed protein by using a stronger promoter or the same promoter as the fusion protein that is expressed at higher levels. If the same promoter is already used for both constructs, it is possible that the placement of the fluorophore has rendered one of the fusion proteins less stable. This can be checked by comparing protein stability for the wild type protein and the fluorophore fusion protein. If the fusion protein is less stable or the fluorophore affects expression of the fusion negatively compared to the wild type protein, consider moving the fluorophore tag to the other end of the protein.

If BiFC does not occur and immunofluorescence staining indicates that the proteins, which normally localize to the same compartment, are not colocalized, consider moving the fluorophore tag to another position on the fusion protein that is aberrantly localized.

If BiFC is not observed with the fusion proteins and these proteins were previously shown to interact by immunoprecipitation experiments, and the western blot analysis indicates that both fusion proteins are expressed equally and immunofluorescent staining indicates that the fusion proteins are localized to the same subcellular compartment, it is possible that the proteins do not interact directly. That is, the interaction between the two proteins may be bridged by another protein or nucleic acid. In this case, FRET, which is a fluorescence approach that requires two proteins to be in nanometer proximity for energy transfer to occur, should be considered to confirm that the two proteins do not interact directly.

Acknowledgments

Our studies using BiFC were supported by NIH NIAID grants AI61397 and AI21215.

3. Appendix

3.1 Equipment

An epifluorescent microscope (we have used a Zeiss Axiovert S100 microscope) or a confocal microscope (we use a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope) is needed to view the cells.

3.2 Supplies

Standard molecular biology reagents are needed for cloning the fusion protein constructs. Plasmid vectors for BiFC including Venus and YFP versions are available from Addgene at: http://www.addgene.org/pgvec1?f=c&cmd=showcol&colid=684

In our studies, mutations introduced into the protein to inhibit interaction were generated using the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Cells for transfection were grown on glass-bottom culture dishes from MatTek Corporation. Lipofectamine 2000 from Invitrogen was used as the transfection reagent. Optimem was obtained from Invitrogen.

For immunofluorescent staining antibody anti-GFP antibody will recognize the N-terminal half of Venus and YFP and was obtained from Clontech, GFP monoclonal mouse antibody – Cat. No. 632375.

References

- 1.Jares-Erijman EA, Jovin TM. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1387–1395. doi: 10.1038/nbt896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenworthy A. Methods. 2001;24:289–296. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sekar RJ, Periassmy A. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:629–633. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu CD, Chinenov Y, Kerppola TK. Mol Cell. 2002;9:796–798. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00496-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerppola TK. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:449–456. doi: 10.1038/nrm1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerppola TK. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:2876–2886. doi: 10.1039/b909638h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerppola TK. Methods Cell Biol. 2008;85:431–470. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)85019-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robida AM, Kerppola TK. J Mol Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.08.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnsson N, Varshavsky A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10340–10344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galameau A, Primeau M, Trudeau LE, Michnick SW. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:619–622. doi: 10.1038/nbt0602-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michnick SW, Remy I, Campbell-Valois FX, Vallée-Bélisle A, Pelletier JN. Methods Enzymol. 2000;328:208–230. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)28399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghosh I, Hamilton AD, Regan L. J American Chemical Society. 2000;122:5658–5668. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shyu YJ, Liu H, Deng X, Hu CD. Biotechniques. 2006;40:61–66. doi: 10.2144/000112036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagai T, Ibata K, Park ES, Kubota M, Mikoshiba K, Miyawaki A. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt0102-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong KA, O’Bryan JP. J Vis Exp. 2011;2643 doi: 10.3791/2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernandez FP, Sandri-Goldin RM. J Virol. 2010;84:4124–4135. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02319-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez FP, Sandri-Goldin RM. mBio. 2010;1(5):e00268-10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00268-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Avitabile E, Forghieri C, Campadelli-Fiume G. J Virol. 2007;81:11532–11537. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01343-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atanasiu D, Whitbeck JC, Cairns TA, Reilly B, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18718–18723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707452104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu CD, Kerppola TK. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:539–543. doi: 10.1038/nbt816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kodama Y, Hu CD. Biotechniques. 2010;49:793–805. doi: 10.2144/000113519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shyu YJ, Suarez J, Hu CD. Nat Protocols. 2008;3:1693–1702. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen IB, Li L, Silva L, Sandri-Goldin RM. J Virol. 2005;79:3949–3961. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.3949-3961.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li L, Johnson LA, Dai-Ju JQ, Sandri-Goldin RM. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1491. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerppola TK. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:465–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]