Abstract

Study Objective:

To evaluate the association between self-reported sleep quality among older adults during inpatient post-acute rehabilitation and one-year survival.

Design:

Prospective, observational cohort study.

Setting:

Two inpatient post-acute rehabilitation sites (one community and one Veterans Administration).

Participants:

Older patients (aged ≥ 65 years, n = 245) admitted for inpatient post-acute rehabilitation.

Interventions:

None.

Measurements and Results:

Within one year of post-acute rehabilitation, 57 participants (23%) were deceased. Cox proportional hazards models showed that worse Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) total scores during the post-acute care stay were associated with increased mortality risk when controlling for amount of rehabilitation therapy received, comorbidities, and cognitive functioning (Hazard ratio [95% CI] = 1.11 [1.02-1.20]). Actigraphically estimated sleep was unrelated to mortality risk.

Conclusions:

Poorer self-reported sleep quality, but not objectively estimated sleep parameters, during post-acute rehabilitation was associated with shorter survival among older adults. This suggests self-reported poor sleep may be an important and potentially modifiable risk factor for negative outcomes in these vulnerable older adults. Studies of interventions to improve sleep quality during inpatient rehabilitation should therefore be undertaken, and the long-term health benefits of improved sleep should be explored.

Citation:

Martin JL; Fiorentino L; Jouldjian S; Mitchell M; Josephson KR; Alessi CA. Poor self-reported sleep quality predicts mortality within one year of inpatient post-acute rehabilitation among older adults. SLEEP 2011;34(12):1715-1721.

Keywords: Aging, rehabilitation, mortality

INTRODUCTION

Several studies have shown that sleep disruption is associated with increased mortality risk among older people. Using polysomnographic data from studies of healthy older adults, Dew et al.1 found that individuals with difficulty falling asleep were at 2.14 times higher risk of death than those without difficulty falling asleep, even when controlling for other predictors. Manabe et al.2 found significantly higher mortality risk among patients in a geriatric hospital who were observed to have nighttime insomnia or difficulty falling asleep, compared to those who slept well, when controlling for other predictors. Studies also show that self-reported hours of nighttime sleep is a robust predictor of mortality, such that too little or too much sleep is associated with higher mortality risk.3–5 Findings related to daytime sleeping/sleepiness are somewhat less consistent. While some studies show that daytime sleeping and daytime sleepiness are associated with higher mortality risk,6,7 others have found this relationship disappears when controlling for other known mortality risk factors.2,8 Taken together, these findings suggest that sleep disturbance may be an important independent mortality risk factor in community settings, and perhaps in institutional settings as well. While acute health events often precipitate a decline in functioning and subsequent death among older individuals, the role of sleep in recovery from acute health events is not well understood. The current study explored the relationship between sleep and mortality among a cohort of older adults recovering from acute health events in an inpatient, “post-acute” rehabilitation setting.

In the present healthcare environment, older people often receive rehabilitation services involving physical, occupational, and other therapies after acute health events in inpatient settings, where the goal of rehabilitative treatment is to improve functional status and facilitate a return to their prior living environment. These post-acute patients are therefore targeted for rehabilitation after acute hospital discharge because of their potential ability to return to independent living.

In our recent work,9 we found that older post-acute rehabilitation patients in inpatient settings suffer from extremely fragmented sleep and have short sleep duration at night. We also found that some patients sleep excessively during the daytime hours. Most importantly, more daytime sleeping (based on behavioral observations of sleep/wake) during the period of post-acute rehabilitation predicted less functional improvement during the rehabilitation stay, even after controlling for known predictors of rehabilitation outcomes (i.e., mental status, hours of rehabilitation therapy received, rehospitalization, and reason for admission). This had long-term implications, such that more daytime sleeping during inpatient post-acute rehabilitation remained a significant predictor of less functional recovery from admission to three months after the inpatient post-acute rehabilitation stay.

To date, identified mortality risk factors in the post-acute setting include depression, age, male gender, and worse functional status prior to the acute health event leading to hospitalization. Morghen et al. found that moderate to severe depression was associated with a three-fold higher risk of institutionalization or death within one year of rehabilitation after hip fracture,10 and Baztan et al. found that older age, male gender, worse functional status before illness, and more functional loss at admission to post-acute care were associated with higher mortality rates within one year.11 With the exception of depression, known mortality risk factors (i.e., age, gender, and pre-illness functional status) are “non-modifiable risk factors” in the post-acute care setting. Sleep disruption may represent a second modifiable risk factor in the post-acute care setting. In the context of these previous studies of mortality after post-acute rehabilitation among older adults,10,11 our findings suggest that sleep may play a role in the relationships observed in other studies. In fact, one possible mechanism through which depression and functional status change might contribute to mortality risk is through disruption of sleep quality.

The current analyses extend our prior work, examining whether sleep disruption among post-acute care patients is associated with mortality within one year of post-acute rehabilitation admission. We explored sleep disturbance specifically because it represents a modifiable risk factor for adverse outcomes among older adults. Based on our prior work, we hypothesized that more self-reported and objectively estimated (by actigraphy) sleep disruption during the post-acute care stay would be associated with higher mortality risk after controlling for other known mortality risk factors.

METHODS

Participants and Setting

The study sample has been described in detail previously.9 Briefly, this was a prospective, observational cohort study among older people admitted to 2 post-acute rehabilitation sites in the Los Angeles area. Site A was a freestanding, for-profit, community nursing home with 130 Medicare-certified beds, which focused on short-term rehabilitation. Site B was an inpatient rehabilitation unit located within a Veterans Administration Medical Center. Research methods were approved by the Veterans Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or (if unable to self-consent) from their responsible party, with the assent of the participant.

All patients admitted to the study sites were approached for screening as soon as possible after admission, always within one week of admission to the rehabilitation unit. Inclusion criteria were: (1) aged 65 years or older; and (2) admitted for rehabilitation (i.e., receiving physical or occupational therapy). Patients were excluded if they (1) resided in a nursing home prior to admission; (2) were unable to participate in the study procedures due to a severe medical illness or behavior disorder. A total of 245 participants (158 from Facility A; 87 from Facility B) were enrolled in the study, and data from all participants are presented here.

Procedures

After admission to the rehabilitation site and enrollment into the study, participants completed a baseline assessment. The assessment included self-report questionnaires (described below) that queried participants about depression, pain, cognitive functioning, sleep disturbance prior to their acute hospitalization, and sleep disturbance in the post-acute care setting. Participants also wore a wrist actigraph to estimate sleep parameters for one week during the post-acute care stay. After discharge from the rehabilitation facility, a structured medical record review was completed. All data were collected by trained research personnel, who were evaluated for adequate interrater reliability throughout the study.

Information on survival and living location was gathered as part of follow-up assessments that were completed 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after enrollment. For those deceased, a date of death was obtained from the next of kin or, for VA patients, from the electronic medical record. Los Angeles County death records were searched when neither the patient nor the next of kin could be reached and there was no medical record documentation that the participant was deceased or evidence the participant was alive (e.g., the medical record indicated they received medical care after the 12-month follow-up date). Among the 245 participants in the sample, we were unable to confirm whether 8 participants were alive or deceased at 1 year (i.e., they could not be reached, no medical record documents were available, and no death records were located). Seven of these individuals were excluded from the survival model (described below) due to missing data on other variables. The remaining participant for whom survival status could not be confirmed was dropped from the analyses. Due to the method of data collection, information on cause of death was not available for participants who were deceased.

Measures

Basic demographic information (age, gender, ethnicity, and education) was recorded for all participants. Hospital and post-acute rehabilitation length of study, the reason for rehabilitation admission (e.g., orthopedic, stroke, medical, surgical) and the amount of rehabilitation therapy received (i.e., physical therapy, occupational therapy, kinesiotherapy) was abstracted from therapists' detailed documentation in the medical record and was quantified as the number of minutes of rehabilitation therapy per day rehabilitation services were offered. Functional independence in personal care and physical activities was assessed at admission by the facilities' physical and occupational therapists using the Functional Independence Measure (FIM). The motor subscale of the FIM (mFIM) was abstracted from the medical record as the main measure of functional status (higher scores indicate greater independence, score range = 13-91).12

Subjective sleep quality was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI),13 an 18-item questionnaire about overall sleep quality (score range 0-21; higher scores indicate more sleep disturbance). For this study, the PSQI was administered twice during the post-acute care stay. On enrollment, participants were queried about their sleep for a one-month period “before their recent illness” (PSQI-pre). As such, the PSQI-pre was intended to describe pre-illness sleep patterns. The PSQI was administered a second time one week after enrollment, and participants were queried about their sleep over the prior week during their post-acute rehabilitation stay (PSQI-7day).

Sleep was objectively assessed with wrist actigraphs (Octagonal Actiwatch-L, Ambulatory monitoring, Inc, Ardsley NY). The actigraph was placed on the participant's dominant arm on the evening of day one, and was removed in the evening 8 days later. To facilitate actigraphy scoring, we asked participants their evening “bedtimes” and morning “rise times” whenever possible; however, participants often had difficulty defining these boundaries of their major sleep period, as their sleep at night was highly disrupted, and they spent most of the day and night in bed. We therefore elected to use a set time interval during which sleep is expected in the inpatient setting; that is, from 22:00 to 06:00 for “nighttime,” and a set time interval during which wakefulness is expected for “daytime”; that is, from 08:00 to 20:00. We have used similar time windows in prior work with older adults in institutional settings.14 For actigraphy scoring the Time Above Threshold (TAT) channel was used with the default scoring algorithm in the Action4 software package (Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc, Ardsley NY).

Other questionnaire assessments included the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),15 which is a 20-item measure of general cognitive functioning (score range = 0-30; higher scores indicate better cognitive functioning) and the 15-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15; score range = 0-15; higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms),16 which is an abbreviated version of the 30-item GDS. Pain was assessed with the pain intensity and frequency components of the Geriatric Pain Measure (GPM; score range 0-29, higher scores indicate worse pain).17

The Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics (CIRS-G)18,19 was used to assess baseline illness severity and comorbidity. The CIRS-G was completed by a trained research registered nurse after a structured medical record review and a brief physical examination of the participant by a study physician. Number of medications received was abstracted from facility medical records.

Statistical Analysis

Other than an expected gender difference (43.0% vs. 96.6% men at facilities A and B, respectively), as previously reported, there were few differences in demographic characteristics across the study sites and no differences in sleep;9 therefore, findings are presented for the combined sample.

Cox proportional hazards models were used to obtain hazard ratios for mortality by PSQI-7day scores, after adjusting for selected covariates. The list of potential covariates included age, gender, ethnicity, education, rehabilitation therapy minutes per day, functional independence (motor component, mFIM), PSQI score pre-illness (PSQI-pre), mini-mental state examination score (MMSE), Geriatric Depression Scale-15 score (GDS-15), modified Geriatric Pain Measure score (GPM), Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatrics score (CIRS-G), number of routine medications, and reason for rehabilitation admission (orthopedic vs. all other). The covariate selection process was based on the model building process described by Hosmer et al.20 beginning with bivariate analyses predicting mortality from each covariate. Covariates with significance levels < 0.20 were included in a multiple predictor model. During this phase of the analysis, we were mindful of the number of covariates in relationship to the number of events (deaths), avoiding entering more than one covariate per 10 events.20 We therefore aimed to limit our final multivariate model to a parsimonious model containing, at most, 3-4 covariates. After excluding nonsignificant terms from the multiple predictor model, nonsignificant predictors from the bivariate models were entered (one at a time) to determine if any of these predictors would be significant in the context of the multiple predictor model or if their inclusion substantially changed the hazard ratios of covariates already selected for inclusion. In all cases, these predictors remained nonsignificant and did not substantially change the hazard ratio for the included covariates.

This covariate selection process yielded four significant covariates: rehabilitation minutes per day, CIRS-G score, reason for rehabilitation admission (orthopedic admission vs. all other), and gender. After controlling for these covariates, the PSQI-7day score was added to form the main analytic model. With 42 events (deaths), there were 8.4 events per predictor. The same covariate set was then used to test models with each of the actigraphically derived sleep variables included. The variable education approached significance as well. We elected to exclude it from the models presented, as it was the weakest of the covariates considered and its inclusion in the model did not impact the pattern of results, that is, the effects of PSQI-7 day score remained the same whether or not education was included in the model. For each model, we ascertained that the proportional hazards assumption was not violated using the score test based on the Schoenfeld residuals (for individual covariates and the overall model) as well as graphical examination of the Schoenfeld residuals across time. The linearity of the predictors was tested using fractional polynomials,21 and none of the predictors showed evidence of non-linearity. Inspection for potential outliers showed no influential data points.

The data analysis was conducted with Stata version 11.1, using the stcox command for the Cox proportional hazards regression models.22

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics and Covariates

Descriptive statistics for all of the potential covariates were computed for the original sample, as well as the participants included in the Cox proportional hazards model (see Table 1). The total sample included 245 participants, whereas the final regression model included a total of 188 participants. This was due to missing data for some subjects on one or more variables included in the final model.

Table 1.

Characteristics of total study sample and the sample used for the survival model (mean, standard deviation, and N for continuous variables; percent, and N for categorical variables)

| Variable | Total sample (N = 245) |

Sample included in survival model (N = 182) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean or % | SD | N | Mean or % | SD | N | |

| Age, in years | 80.6 | 7.2 | 245 | 80.2 | 7.1 | 188 |

| Gender (% female and N) | 38.0 | – | 245 | 35.6 | – | 188 |

| Ethnicity (% non-Hispanic white and N) | 79.6 | – | 245 | 77.6 | – | 188 |

| Education, years | 13.9 | 3.4 | 237 | 13.8 | 3.3 | 183 |

| Acute hospital length of stay (days) | 10.8 | 15.8 | 245 | 11.1 | 17.1 | 188 |

| Rehabilitation length of stay (days) | 21.4 | 14.5 | 245 | 21.2 | 11.6 | 182 |

| Rehabilitation therapy received (min/day) | 77.9 | 29.0 | 245 | 77.2 | 27.7 | 188 |

| Functional Independence Measure, motor component (mFIM) | 44.8 | 12.5 | 245 | 45.7 | 12.2 | 188 |

| Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) | 23.5 | 6.2 | 228 | 24.5 | 5.1 | 185 |

| Geriatric Depression Scale-15 (GDS-15) | 4.1 | 3.3 | 228 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 185 |

| Modified Geriatric Pain Measure (GPM) | 46.3 | 28.2 | 239 | 46.1 | 27.6 | 188 |

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatrics (CIRS-G) | 22.6 | 5.9 | 245 | 22.6 | 5.9 | 188 |

| Reason for rehabilitation (% orthopedic admission) | 36.7 | – | 245 | 36.2 | 188 | |

| Number of routine medications | 15.9 | 7.2 | 244 | 16.2 | 7.3 | 187 |

| PSQI prior to admission (PSQI-pre) | 5.2 | 3.8 | 214 | 5.3 | 3.7 | 176 |

| PSQI 7 days after admission (PSQI-7day) | 8.3 | 4.4 | 191 | 8.4 | 4.4 | 188 |

| Actigraphy nighttime hours of sleep | 5.1 | 2.1 | 241 | 5.0 | 2.1 | 187 |

| Actigraphy nighttime % sleep | 54.9 | 21.5 | 241 | 54.6 | 21.3 | 187 |

| Actigraphy nighttime number of awakenings | 15.6 | 6.8 | 241 | 15.7 | 6.5 | 187 |

| Actigraphy daytime hours of sleep | 2.1 | 1.6 | 241 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 187 |

| Actigraphy daytime % sleep | 15.8 | 12.1 | 241 | 15.4 | 11.5 | 187 |

Covariates were compared for the participants included in the model versus those excluded by the model due to missing data. Significant differences were found for MMSE (with the excluded sample showing significantly lower MMSE scores (P < 0.001), and mFIM at admission (with excluded participants showing significantly lower mFIM scores; P = 0.031). No significant differences were found for the remaining covariates examined.

Mortality

In the entire sample of N = 245, there were 57 deaths (23.3%), with an average of 313.2 days (SD = 108.1) from enrollment to death. Among the participants included in the model (N = 188) there were 42 deaths (22.3%) with an average of 316.6 days (SD = 103.7) from enrollment to death. The median time from enrollment to death was 365 days for the overall sample, as well as for the participants included in the model.

Self-Reported Sleep Quality and Mortality

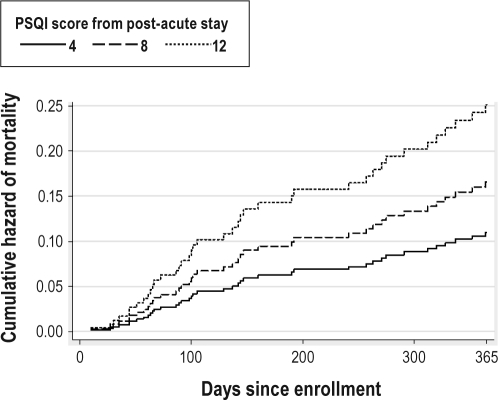

The Cox regression model predicting mortality is shown in Table 2. After adjusting for amount of rehabilitation therapy, CIRS-G, reason for rehabilitation admission, and gender, higher PSQI-7day scores were associated with greater hazard of mortality (HR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.04-1.21). In other words, for every 1-point increase in PSQI-7day score, the predicted risk of mortality increased by 12% (95% CI = 2%-21%). Figure 1 shows the cumulative hazard of mortality by days since enrollment for this model using three selected PSQI-7day scores (4, 8, and 12) corresponding to the 3 quartiles in this sample. As mentioned, the inclusion of education as an additional covariate did not change the pattern of the results.

Table 2.

Results of Cox proportional hazards model predicting mortality from PSQI-7day scores and selected covariates

| Variables* | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| PSQI-7day | 1.12 (1.04, 1.21) | 0.001 |

| Rehabilitation therapy received (min/day) | 0.98 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.001 |

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatrics (CIRS-G) | 1.11 (1.05, 1.17) | 0.001 |

| Reason for rehabilitation (orthopedic) | 0.38 (0.16, 0.92) | 0.033 |

| Gender (female) | 2.51 (1.31, 4.83) | 0.006 |

Overall Model: N = 188, LR χ2 = 48.17, df = 5, P < 0.0001.

Figure 1.

Cumulative hazard of mortality by days since enrollment in study for three selected PSQI-7day scores based on the model.

To further understand the results of the model predicting mortality from total PSQI score, follow-up analyses were performed entering each of the 3 PSQI subscale scores (Subjective Sleep Quality, Sleep Efficiency, and Daily Disturbances)23 in place of the PSQI total score. After adjusting for the covariates, the Subjective Sleep Quality subscale score was significantly related to mortality (HR = 1.85, P < 0.001), as was the Sleep Efficiency subscale score (HR = 1.37, P = 0.011). The Daily Disturbances subscale score (HR = 1.11, P = 0.590) was not related to mortality. The same pattern of results was found entering all 3 PSQI subscale scores (as well as the covariates) into a single model; that is, mortality was associated with the Subjective Sleep Quality (P = 0.003) and Sleep Efficiency (P = 0.043) subscale scores, but not to the Daily Disturbances subscale score (P = 0.967).

Actigraphically Estimated Sleep and Mortality

Mortality was also modeled as a function of objectively estimated sleep parameters derived from wrist actigraphy, namely number of minutes of nighttime sleep, percent of time asleep at night, mean number of awakenings at night, number of minutes asleep during the day, and percent of time asleep during the day. After adjusting for the previously mentioned covariates, none of these measures of objective sleep were significantly related to mortality.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective study of older people in the post-acute rehabilitation setting, the 1-year mortality rate was high (23%) compared to death rates for individuals over age 65 in the U.S. population, which ranged from 2.1% for those age 65-74 to 13.8% for those age 85 and older in 2005 according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.24 Studies of similarly aged post-acute rehabilitation patients have found 1-year mortality rates similar to those in our study. One study found mortality rates of 14% for orthopedic patients, 17% for stroke patients, and 32% for deconditioned patients.11 Another study found that 17.9% of individuals admitted following hip fracture were deceased or institutionalized within 1 year.10 Taken together, these studies suggest older adults who receive post-acute care have higher mortality risk than the general population, likely due to the precipitating health events leading to the rehabilitation stay or to comorbid medical conditions in these patients. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine sleep as a potential mortality predictor among older adults in the post-acute care setting. In survival analyses, self-reported sleep quality during post-acute care (PSQI-7day) emerged as a significant predictor of survival in a model adjusting for minutes of rehabilitation therapy per day, gender, reason for rehabilitation admission, and comorbidities (CIRS-G score). In addition to poor sleep quality, receiving less therapy, female gender, admission for a reason other than orthopedic rehabilitation, and more comorbidities predicted shorter survival. With the exception of gender, these are consistent with the expected direction of these relationships. The increased mortality risk for women in this sample was likely a result of subtle differences in the characteristics of patients at the two sites (e.g., slightly older age) as most women were enrolled at the community site.

The magnitude of the impact of sleep disturbance on survival was not trivial. A 1-point increase in self-reported sleep disturbance on the PSQI was associated with a 12% increase in mortality risk. We previously reported that the PSQI-7day was, on average 3 points higher than the pre-illness PSQI score for this sample,9 suggesting that improving sleep to the pre-illness level might result in substantially reduced mortality risk. Also, a recent study of a brief behavioral treatment for insomnia among older adults found a 4-point reduction in PSQI score with active treatment (and no change in controls).25 Behavioral treatments to improve sleep quality in the post-acute care setting may therefore be beneficial.

Our follow-up analyses examining the three subscales of the PSQI do suggest that nighttime sleep represented by the Sleep Quality and Sleep Efficiency subscales were more strongly associated with mortality risk than the Daytime Dysfunction subscale in this sample. This is in line with previous work showing that self-reported nighttime sleep is a consistent mortality risk factor,1–5 while daytime sleeping and daytime sleepiness2,6–8 are less consistently associated with elevated mortality risk. In our study, we did find that daytime sleeping (rather than nighttime sleep measures) predicted reduced functional improvement during rehabilitation after controlling for other known predictors of functional improvement in rehabilitation settings9; however, daytime sleeping (based on PSQI self-report or actigraphically estimated daytime sleep) was not related to mortality risk. This suggests a complex picture in which daytime sleeping (or daytime sleepiness) and nighttime sleep disruption (or poor self-reported sleep quality) may operate in different ways during illness recovery. Additional research on the interactions between daytime sleeping and nighttime sleep quality during illness recovery is needed.

A key consideration is the role of acute sleep disturbance in the post-acute care setting versus chronic sleep disturbance. Our findings suggest that acute sleep disturbance during illness recovery, regardless of sleep quality prior to the illness onset, may contribute to negative outcomes for older patients, as the pre-illness PSQI score was not significantly associated with mortality risk. This is particularly critical given the literature suggesting that sleep quality in hospital and nursing home settings is poor,26 and that some causes of sleep disruption, such as noise, light, and caregiving interruptions, could be reduced.27

Also of interest, actigraphically estimated sleep measures were not related to mortality. Many previous studies have documented discrepancies between self-reported and objectively measured sleep, making this finding somewhat less surprising. Nonetheless, the absence of a relationship between objective sleep quality (estimated by actigraphy) and mortality supports the notion that the two constructs are different. Perhaps the self-reported sleep quality captured by the PSQI represents a more complex phenomenon than the objectively quantified sleep captured by the actigraph. It is possible that poor self-reported sleep quality is the result of a constellation of symptoms, including real sleep disturbance, recognition that sleep is more disturbed than it should be, and an ability to describe this sleep disturbance on questionnaires. It may be the combination of these factors that predicts shorter survival, while sleep disturbance on its own may not be sufficiently disruptive to increase mortality risk in this population.

The precise mechanisms underlying the relationships between self-reported sleep and mortality are not entirely clear. One plausible hypothesis is that sleep disruption is a marker for underlying medical morbidity, and there are data suggesting that the number and severity of medical conditions is related to sleep problems among older people.28 Studies controlling for medical comorbidities, however, still demonstrate that both short sleep and long sleep are associated with higher mortality risk.1,3,8 Alternatively, disrupted sleep may predict, either as a cause or as a prodromal symptom, adverse health events such as falls, cardiovascular disease, or stroke. Finally, chronic poor sleep may lead to chronic stress and disease, which then ultimately lead to poor health and higher mortality risk. In addition, studies have found depression to be a significant predictor of attenuated functional gains with rehabilitation and of increased risk of death or institutionalization after rehabilitation.10 Since sleep disturbance is a hallmark symptom of depression, and sleep has not been routinely assessed in these studies of depression, it is difficult to draw conclusions. Given that, in our study, depression was not a significant predictor of mortality when sleep variables were examined concurrently, our findings suggest poor sleep may be an important component of depression that contributes to mortality risk. Future research on depression in post-acute care settings should attempt to tease apart the independent role of sleep disturbance.

This study has several limitations to be considered. First, we did not use polysomnographic sleep recordings to objectively characterize sleep architecture, and pre-illness sleep quality was assessed retrospectively. Due to the relatively short length of the post-acute care stay, we used an adapted version of the PSQI in which respondents were asked to describe sleep over the prior week (rather than over the prior month). While we have not fully validated this method, in our preliminary work we found a high correspondence between one-month and one-week versions of the PSQI. Because of methodological limitations, the lack of a relationship between pre-illness sleep problems and mortality must be interpreted with caution. Second, given participants with missing data showed signs of greater impairment (lower MMSE, and lower mFIM scores) but had to be excluded from the analysis, questions remain about whether this relationship would persist among the most frail and impaired individuals in post-acute care. Also, the survival status of eight participants could not be confirmed, and information on cause of death was not available for any. Understanding the specific cause of death would further our understanding of the mechanisms that may underlie the relationship between worse self-reported sleep quality during post-acute care and increased mortality risk.

In summary, our findings suggest that, even after controlling for other risk factors, more self-reported sleep disturbance during inpatient post-acute rehabilitation is a significant predictor of mortality within one year among older people. Since sleep disturbance in the inpatient setting represents a potentially modifiable risk factor, and empirically supported non-pharmacological treatments are available, targeted interventions to improve sleep during the post-acute care stay should be explored.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest. Portions of these findings were presented at the June 2008 meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies in Baltimore, MD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the participating facilities and their staff, and the members of the research team who made this study possible. In particular, the authors thank Terry Vandenberg, MA, Sergio Martinez, Maryanne Devereaux, Christina Kurtz, RN, Rebecca Saia, Crystal Barker, RN, Jae Lee, MD, David Kim, PA, and Adam Webber, BSc(Hons), MRCP (UK). This study was supported by NIA K23 AG028452; VA HSR&D (IIR-01-053-1; IIR 04-321-2; AIA-03-047), NIMH T32 MH 019925-11, NIMH T32 MH019934, and VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC).

Footnotes

A commentary on this article appears in this issue on page 1627.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dew MA, Hoch CC, Buysse DJ, et al. Healthy older adults' sleep predicts all-cause mortality at 4 to 19 years of follow-up. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:63–73. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000039756.23250.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manabe K, Matsui T, Yamaya M, et al. Sleep patterns and mortality among elderly patients in a geriatric hospital. Gerontology. 2000;46:318–22. doi: 10.1159/000022184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler M. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:131–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burazeri G, Gofin J, Kark JD. Over 8 hours of sleep--marker of increased mortality in Mediterranean population: follow-up population study. Croatian Med J. 2003;44:193–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Youngstedt SD, Kripke DF. Long sleep and mortality: rationale for sleep restriction. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8:159–74. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hays JC, Blazer DG, Foley DJ. Risk of napping: excessive daytime sleepiness and mortality in an older community population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:693–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newman AB, Spiekerman CF, Enright P, et al. Daytime sleepiness predicts mortality and cardiovascular disease in older adults. The Cardiovascular Health Study Research Group. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:115–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rockwood K, Davis HS, Merry HR, MacKnight C, McDowell I. Sleep disturbances and mortality: results from the Canadian study of health and aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:639–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alessi CA, Martin JL, Webber AP, et al. More daytime sleeping predicts less functional recovery among older people undergoing inpatient post-acute rehabilitation. Sleep. 2008;31:1291–1300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morghen S, Bellelli G, Manuele S, Guerini F, Frisoni GB, Trabucchi M. Moderate to severe depressive symptoms and rehabilitation outcome in older adults with hip fracture. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1002/gps.2651. online early. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baztan JJ, Galvez CP, Socorro A. Recovery of functional impairment after acute ilness and mortality: one-year follow-up study. Gerontology. 2009;55:269–74. doi: 10.1159/000193068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ottenbacher K, Mann W, Granger C, Tomita M, Hurren D, Charvat B. Inter-rater agreement and stability of functional assessment in the community-based elderly. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:1297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CFI, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alessi CA, Martin JL, Webber AP, Kim EC, Harker JO, Josephson KR. Randomized controlled trial of a nonpharmacological intervention to improve abnormal sleep/wake patterns in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:619–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5:165–72. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrell BA, Stein WM, Beck JC. The Geriatric Pain Measure: validity, reliability and factor analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1669–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, et al. Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Res. 1992;41:237–48. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90005-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parmelee PA, Thuras PD, Katz IR, Lawton MP. Validation of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale in a greiatric residential population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:130–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, May S. Applied survival analysis: regression modeling of time to event data. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ambler G, Royston P. Fractional polynomial model selection procedures: investigating type I error rate. J Stat Comput Simul. 2001;69:89–108. [Google Scholar]

- 22.College Station, TX: StataCorp; 2009. Stata: Release 11. Statistical Software. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cole JC, Motivala SJ, Buysse DJ, Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Irwin MR. Validation of a 3-factor scoring model for the Pittsburgh sleep quality index in older adults. Sleep. 2006;29:112–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [accessed 9/15/2009]. Death rates by age and age-adjusted eath rates for the 15 leading causes of death in 2005: United States, 1999-2005. [serial online] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Germain A, Moul DE, Franzen PL, et al. Effects of a brief behavioral treatment for late-life insomnia: preliminary findings. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:403–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ersser S, Wiles A, Taylor H, Wade S, Walsh R, Bentley T. The sleep of older people in hospital and nursing homes. J Clin Nurs. 1999;8:360–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.1999.00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cmiel CA, Karr DM, Gasser DM, Oliphant LM, Neveau AJ. Noise control: a nursing team's approach to sleep promotion. Am J Nurs. 2004;104:40–8. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200402000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, Walsh J. Sleep disturbance and chronic disease in older adults: Results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America survey. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]