Abstract

Background:

Anterior encephaloceles are rare conditions. Except for a few places from South East Asia, no large series has been published in the World literature.

Materials and Methods:

At AIIMS, we have managed 133 cases over a 40-year-period from 1971 to 2010. Frontoethmoidal type was the most frequent, noticed in 104 patients, followed by nasopharyngeal nasal in 12 and orbital encephaloceles in 6 patients.

Observation:

Ten patients were adults over the age of 18 years and 15 patients were between 5 and 18 years of age. Swelling over the nose was reported in all 104 patients with frontoethmoid type. In nasopharyngeal type, patients presented with respiratory problem. Patients with orbital mass had proptosis, on the side of encephalocele. Computed tomography (CT)/Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed in 127 patients, which was able to delineate the bone defect and associated brain anomalies. All the patients were subjected to repair of encephalocele. Patients with hypertelorism required orbital osteotomies and correction of deformity.

Outcome:

There were four deaths, all prior to 2000. No death was encountered in the last 10 years. CSF leak was the commonest postoperative complication, noticed in 24 patients. Overall cosmetic outcome was good.

Keywords: Anterior encephalocele, bone defect, brain anomalies, good outcome, one-stage surgery

Introduction

Anterior encephaloceles are neural tube defects and a very rare condition. From some part of South East Asia, a higher incidence has been reported.[1–5] There are only a few large series published in the World literature.[6–9] Our series of 133 cases of anterior encephalocele is probably the largest series in the World literature.

Materials and Methods

Between 1971 and May 2011, 133 cases of anterior encephaloceles have been treated at our department at AIIMS. The number of cases has remained similar over the last 30 years, ranging from three to four cases on an average per year. Even in the last 10 years, among 110 encephaloceles, only 30 cases belonged to anterior encephalocele category. Only 50% patients reported to us in less than 3 months and 70% patients in less than 1 year. Surprisingly, 10% patients were above the age of 5 years. We have 10 patients above the age of 18 years.

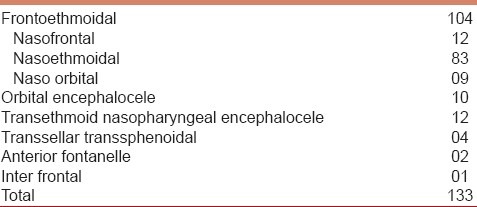

The commonest type was frontoethmoid type noticed in 104 patients [Figure 1], followed by transethmoidal nasopharyngeal type in 12 patients [Figure 2] and orbital encephaloceles in 10 patients. Rare types like anterior frontal and transsellar transsphenoidal type were observed in two and four cases, respectively. Among the subgroups of frontoethmoidal type, nasoethmoid type was recorded in 83 and nasofrontal in12 patients. Naso-orbital type was the lowest, recorded in 9 patients [Table 1].

Figure 1.

A 6-month-old child with nasoethmoid type of encephalocele

Figure 2.

Clinical photograph of a 3-year-old child with nasofrontal type

Table 1.

Types of encephaloceles in 133 patients

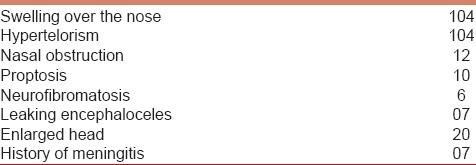

Clinical features were very specific to each subgroup. All the patients of frontoethmoidal subtype had a swelling either over bridge of the nose or at the root of the nose, with some degree of hypertelorism. In patients with orbital encephaloceles, proptosis was the key presentation, noticed in 10 patients. Nasopharyngeal and transsellar transsphenoid subtypes had nasal and respiratory obstruction as the prominent feature. Twelve had history of CSF rhinorrhea, five following biopsy from nasal or nasopharyngeal mass, which was misdiagnosed as nasal polyp, by the ENT Surgeon. Enlarged head was noticed in 20, which was the result of associated hydrocephalus, either of congenital origin or following meningitis [Table 2].

Table 2.

Clinical features

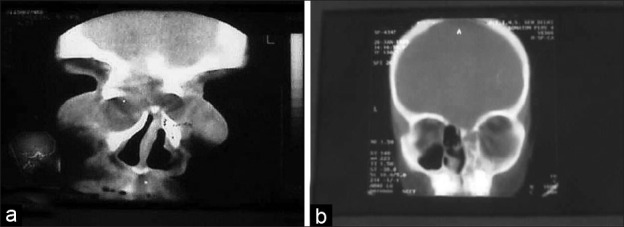

Computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan has been available since 1978 and was performed in 129 patients [Figure 3a and b]. Associated hydrocephalus was noticed in 22 and corpus callosum agenesis in 16 patients. Five patients had cortical dysplasia. Nasopharyngeal mass and orbital mass were recorded in 12 and 10 patients, respectively. Five patients had porencephalic cyst and one patient each had arachnoid cyst and chronic subdural hematoma [Table 3].

Figure 3.

(a) CT scan shows a classical nasoethmoid type. (b) Coronal CT showing transethmoid nasopharyngeal encephalocele

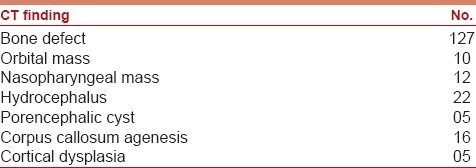

Table 3.

CT scan/MRI findings in 127 patients

Surgical procedure

Surgery was considered for repair of the encephalocele and correction of the deformity. Twenty of 22 patients with hydrocephalus underwent ventriculo peritoneal (VP) shunt for the CSF diversion. Patients with transsellar transsphenoidal encephalocele had transpalatal repair. Patients with orbital and transethmoidal nasopharyngeal encephaloceles underwent bicoronal bone flap and repair of encephalocele with duraplasty. Recently, over the last 30 years, glue has been frequently used for the dura closure. Half of the orbital encephaloceles with sphenoid wing dysplasia had bone graft to reconstruct the sphenoid wing [Table 4].

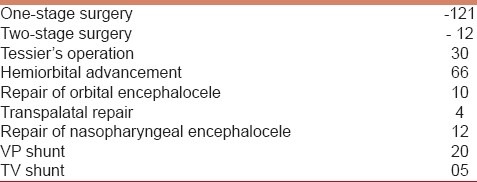

Table 4.

Types of surgery in 133 patients

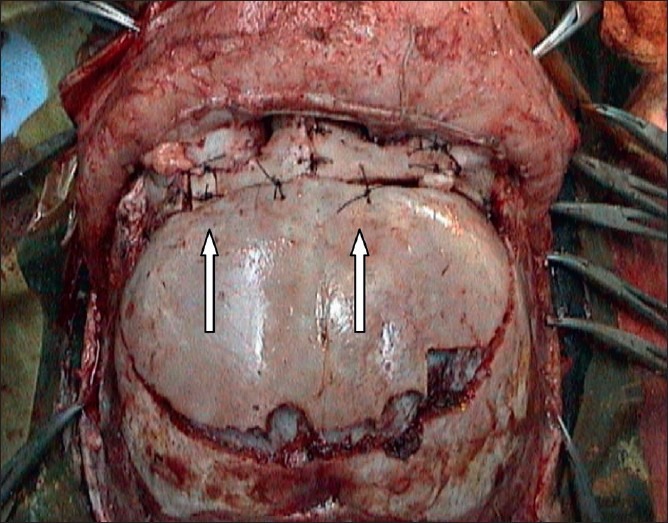

Among the 104 patients with frontoethmoidal encephaloceles, 30 patients had classical Tessier′s operation where bilateral orbital advancement was carried out to correct the hypertelorism [Figure 4]. Since 1990, hemiorbital advancement has been carried out as described by Mahapatra elsewhere.[6,7] The hemiorbital advancement is less time consuming and less traumatic with similar cosmetic results. Hemiorbital advancement was undertaken in 66 patients [Figure 5]. Five patients with postoperative persistent CSF leak underwent percutaneous thecoperitoneal shunt, which was effective to stop CSF leak [Table 4].

Figure 4.

Intraoperative photograph showing correction of hypertelorism (black arrows)

Figure 5.

The intraoperative photograph after correction of hypertelorism by hemiorbital advancement (white arrows)

Outcome

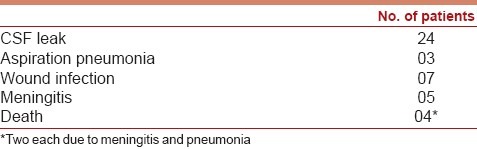

CSF leak/CSF rhinorrhea was the most frequent postoperative complication, recorded in 24 patients of whom 5 required Thecoperitoneal (TP) shunt [Table 5]. Five patients developed postoperative meningitis for which appropriate antibiotics were prescribed for a period of 2-3 weeks. Seven patients developed wound infection and one had osteomyelitis. Overall, 80% had no postoperative problem and were discharged between 7 and 10 days of surgery. Patients were followed up 3 monthly between 1 and 10 years. Only 15% patients had a follow-up more than 3 years. Overall cosmetic outcome was good and over 50% had normal schooling.

Table 5.

Postoperative complications

Discussion

Despite the reduction of incidence of neural tube defects (NTDs) in the West, in countries like India, NTD is a major problem for the neurosurgeons, especially for the pediatric neurosurgeons. Being a tertiary referral center, at AIIMS, we get large number of patients with NTD including encephaloceles.

Overall, anterior encephaloceles are rare and we have collected 133 cases over a period of 40 years.[6,7,10] No doubt, it is a large number and it reflects the referral system and status of national hospital of our Institute. Suwanwela and Suwanwela[8,11] published several series in the 1970s. From India,[4] we have published several reports in the last 20 years.[10,12,13]

Frontoethmoidal type is the commonest type reported in the literature.[3,6,7,11,14,15] The next common type is the frontonasal type.[6–8,11] Transsellar transsphenoid encephaloceles are rare and less than 30 cases have been reported in the literature.[9,12] We have so far collected four cases.[12]

Seventy percent patients were less than 1 year of age and 10% were older than 5 years. We preferred surgery around 9-10 months of age, as this is the time when the patient can stand a prolonged surgery. Surprisingly, more than 30% patients reported to us after 1 year. Lack of awareness on the part of general practitioners and pediatricians delayed the referral to a tertiary center.

Among the patients, swelling over the nose and hypertelorism is the commonest finding.[3,5,7,8,11,16]

Tessier defined the facial anomalies in the year 1969 and described the various facial anomalies along with the different clefts in the year 1976. More than 80% of our patients had varying degrees of hypertelorism. Nasal obstruction is common in nasal encephalocele.[9,12,14,15] Nasal masses also can lead to CSF rhinorrhea, either spontaneously or after surgical trauma due to biopsy. Hydrocephalus is rare in anterior encephaloceles. Only 10-15% do have associated hydrocephalus.[6,7,12] In the present study, 22 patients had hydrocephalus and 16 patients had corpus callosum agenesis.

Needless to say, all encephaloceles need surgery. Meticulous planning is necessary for surgery, depending on the type and size of encephalocele and associated hydrocephalus.[3,5,7,10,12,14,15,17] By and large, emergency operation is avoided unless there is leaking encephalocele,[13] which is a must to prevent meningitis. In six of our patients, there was history of meningitis. Twenty of 22 patients in our study underwent VP shunt. The factors influencing the surgery are (a) type of encephalocele, (b) degree of hypertelorism, (c) associated anomalies, (d) presence or absence of respiratory obstruction and (e) associated CSF leak. Only six of our patients had craniofacial surgery at neonatal period, as they presented with emergency. Except the patients with transsellar transsphenoid encephalocele, the rest 129 patients had undergone bicoronal craniotomy and exploration of anterior cranial fossa floor. Classical osteotomy described for hypertelorism, by Prof. Tessier in 1969,[17] was performed in 30 patients.[10] In 66 patients, a hemiorbital advancement was carried out to correct the hypertelorism.[6,7] This technique was described by Mahapatra in late 1980s and published subsequently in several papers.[6,7] This technique is of tremendous advantage due to reduction of time and blood loss, so also less damage to the tissue around the orbit. Overall cosmetic outcome following hemiorbital advancement is good and comparable to classical Tessier′s operation.

Postoperative CSF leak is the major complication reported in 10-15% cases.[6,7,10,15–17] However, by and large, CSF leak is transient and subsides with conservative management and repeated CSF drainage from lumbar theca.[6,7,10] We had CSF leak in 24 patients and only 5 required percutaneous TP shunt, as CSF leak persisted beyond 7-10 days. We had an overall good cosmetic result. Only 20 patients (15%) had follow-up for more than 3 years. However, only 30% had only lower IQ than normal. More than 50% had normal schooling with fair performance.

Conclusions

We have collected one of the largest series of anterior encephalocele in the World literature. Frontoethmoidal type is the commonest and associated with hypertelorism. Nasal obstruction is common in nasopharyngeal type. We performed hemiorbital advancement to correct hypertelorism, which reduced the surgical time significantly. CSF leak is the most common postoperative problem. The overall outcome was good.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Aung Thu, Hta Kyu. Epidemiology of frontoethmoidal encephalocele and in Burma. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1984;38:89–98. doi: 10.1136/jech.38.2.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.David DJ. New perspective in management of sever craniofacial deformity. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1984;66:170–279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoving EW, Vermeij-Keers C. Frontoethmoidal encephaloceles, a study of their pathogenesis. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1999;27:246–56. doi: 10.1159/000121262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kak VK, Gulati DR. The familial occurrence of frontoethmoidal encephaloceles. Neurol India. 1973;21:41–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tessier P. Anatomical classification of facial, craniofacial and laterofacial clefts. J Maxillofac Surg. 1976;6:69–92. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(76)80013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahapatra AK, Suri A. Anterior encephalocele-A study of 92 cases. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2002;36:113–8. doi: 10.1159/000048365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahapatra AK, Agrawal D. Anterior encephalocele-A series of 103 cases over 32 years. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13:536–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suwanwela C. Geographical distribution of fronto-ethmoidal encephalomeningocele. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1972;26:193–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.26.3.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma RR, Mahapatra AK, Pawar SJ, Thomas C, Ismaly M. Transsellar Transsphenoid encephalocele-A report of two cases. J Clin Neurosci. 2001;9:89–92. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahapatra AK, Tandon PN, Dhawan IK, Khazanchi RK. Anterior encephaloceles-A report of 30 cases. Childs Nerv Syst. 1994;10:501–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00335071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suwanwela C, Suwanwela N. A morphological classification of sincipital encephaloceles. J Neurosurg. 1972;36:201–11. doi: 10.3171/jns.1972.36.2.0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rathore YS, Sinha S, Mahapatra AK. Transsellar transsphenoidal encephalocele: A series of four cases. 2011;59:289–92. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.79157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satyarthee GD, Mahapatra AK. Craniofacial surgery for giant frontonasal encephalocele in neonate. J Clin Neurosci. 2002;9:593–5. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2001.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta DK, Mahapatra AK. Transethmoidal transpharyngeal nasal encephalocele: Neuroimaging. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2006;42:335–7. doi: 10.1159/000094075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rehman NI. Nasal encephalocele treated by a transcranial operation. J Neurol Sci. 1979;42:73–95. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(79)90153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turgut M, Ozcan OE, Benli K, Ozgen T, Gürçay O, Sağlam S, et al. Congenital nasal encephalocele: A review of 35 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1995;23:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80246-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tessier P, Guiot G, Rougerie J, Delbet JP, Pastoriza J. Cranio-naso-orbitofacial osteotomies. Hypertelorism. Ann Chir Plast. 1967;12:103–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]