Abstract

The CgrA and CgrC proteins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa are coregulators that are required for the phase-variable expression of the cupA fimbrial genes. Neither CgrA nor CgrC resembles a classical transcription regulator, and precisely how these proteins exert their regulatory effects on cupA gene expression is poorly understood. Here, we show that CgrA and CgrC interact with one another directly. We identify a mutant of CgrC that is specifically defective for interaction with CgrA and demonstrate that this mutant cannot restore the phase-variable expression of the cupA fimbrial genes to cells of a cgrC mutant strain. Using this mutant, we also show that CgrC associates with the cupA promoter regardless of whether or not it interacts with CgrA. Our findings establish that interaction between CgrA and CgrC is required for the phase-variable expression of the cupA fimbrial genes and suggest that CgrC exerts its regulatory effects directly at the cupA promoter, possibly by recruiting CgrA. Because the regions of CgrA and CgrC that we have identified as interacting with one another are highly conserved among orthologs, our findings raise the possibility that CgrA- and CgrC-related regulators present in other bacteria function coordinately through a direct protein-protein interaction.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative bacterium that is an important opportunistic pathogen of humans; the organism is notorious for being the principal cause of morbidity and mortality in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients. Chronic colonization of the CF lung by P. aeruginosa often leads to progressive lung damage, eventually resulting in respiratory failure and death (13). In the CF lung the organism is thought to persist as a biofilm, forming clusters of cells encased in a polymeric matrix (26). This biofilm mode of growth engenders increased resistance to antibiotics and facilitates the evasion of the host immune system (7). The microbial environment in the CF lung is thought to be largely anaerobic or microaerophilic (36), and it is believed that cells of P. aeruginosa persist in the CF lung in anaerobic biofilms, which are more robust than the biofilms the organism makes under aerobic conditions (37).

Among the genes that play a role in biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa are the cupA genes, which encode components and assembly factors of a fimbrial structure that facilitates surface attachment (15, 18, 30). Although it is not known whether CupA fimbriae contribute to biofilm formation in the CF lung, the cupA3 gene of a P. aeruginosa strain isolated from a CF patient has been shown to be required for the chronic infection of the rat lung (35), suggesting that CupA fimbriae play a role in host colonization.

The regulation of cupA gene expression is complex. Under typical laboratory growth conditions, the expression of the cupA genes is tightly repressed by the H-NS family member MvaT (31–33), which appears to bind directly to the cupA promoter region (3). In the absence of MvaT the cupA genes are expressed in a phase-variable manner (i.e., expressed in a reversible on-off fashion) (32). Similarly, the cupA genes are expressed in a phase-variable manner when wild-type (mvaT+) cells of P. aeruginosa are grown under anaerobic conditions (33). The link between cupA gene expression and anaerobiosis appears to be mediated by the global regulator Anr, which likely mediates its effects by activating the expression of three other positive regulators of cupA gene expression encoded by the cgrABC genes (33). The cgrABC genes map immediately upstream of the cupA gene cluster in a putative operon, and all three of the cgr genes are required for phase-variable cupA expression.

The products of the cgrABC genes represent an unusual set of coregulators. Sequence analysis and structural prediction algorithms suggest that CgrA is a member of the adenine nucleotide α-hydrolase superfamily. This family of proteins includes the phosphoadenosine/adenosine phosphosulfate (PAPS/APS) reductases, ATP sulfurylases, and N-type ATP pyrophosphatases (24). CgrB is a putative member of the GNAT family of acetyl transferases that often function by acetylating the lysine residues of target proteins (34), whereas CgrC is predicted to be a member of the ParB family of DNA-binding proteins, which typically contain a helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif and often are involved in DNA partitioning (14, 25). How the Cgr proteins positively regulate the expression of the cupA genes is not known.

Here, we demonstrate that CgrA and CgrC interact with one another and that this interaction is required for the phase-variable expression of the cupA genes. These findings have implications for how CgrA- and CgrC-related regulators function in other bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and chemicals.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains PAO1, PAO1 ΔmvaT cupA lacZ, and PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ have been described previously (32, 33). Escherichia coli DH5αF′IQ (Invitrogen) was used as the recipient strain for all plasmid constructions. E. coli strain KDZif1ΔZ (32) was used as the reporter strain for the bacterial two-hybrid assays. A list of oligonucleotide primers used in this study is provided in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

When growing E. coli, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: gentamicin (15 μg ml−1), carbenicillin (100 μg ml−1), tetracycline (10 μg ml−1), and kanamycin (50 μg ml−1). When growing P. aeruginosa, gentamicin (30 μg ml−1) was used. Phase-ON and phase-OFF colonies of the PAO1 ΔmvaT cupA lacZ and PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ reporter strains were visualized following growth on LB agar containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) (75 μg ml−1).

Strain PAO1ΔmvaT cgrA(FS) cupA lacZ contains a mutation in cgrA that results in a frameshift following codon 45 and therefore does not express the cupA genes in a phase-variable manner. The strain is a derivative of PAO1 ΔmvaT cupA lacZ (32) and was made by allelic replacement using plasmid pEXG2-pcgrA(FS). Plasmid pEXG2-pcgrA(FS) was constructed in two steps. First, a 1,050-bp region of DNA, from 300 bp upstream of the translation start of cgrA to 700 bp downstream of the translation start of cgrA, was cloned into plasmid pEXG2 (20) on a HindIII-KpnI fragment, making plasmid pEXG2-pcgrA. Second, a portion of pEXG2-pcgrA DNA then was replaced with DNA containing an additional base pair following codon 45 of cgrA, making plasmid pEXG2-pcgrA(FS).

Strain PAO1ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ attTn7::TOPLACUV5-V-cgrC contains a construct that directs the synthesis of N-terminally vesicular stomatitis virus-glycoprotein (VSV-G)-tagged CgrC under the control of an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter. This construct is stably integrated into the genome in a single copy at the att-Tn7 locus. Similarly, strain PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ attTn7::TOPLACUV5-V-cgrC(L197S) contains a construct that directs the synthesis of N-terminally VSV-G-tagged CgrC(L197S). These strains were constructed using the plasmids pUC18-mini-Tn7T-TOPLACUV5-V-cgrC and pUC18-mini-Tn7T-TOPLACUV5-V-cgrC(L197S), respectively, and the antibiotic resistance selection marker present on the chromosomally integrated mini-Tn7 element was excised using Flp recombinase as previously described (6). A third strain was constructed in which the empty vector pUC18-mini-Tn7-TOPLACUV5 was integrated into the chromosome at the att-Tn7 locus, and the antibiotic resistance determinant was removed by Flp-mediated excision (6). The plasmid pUC18-mini-Tn7-TOPLACUV5 is a derivative of pUC18-mini-Tn7-TOPLAC (29) in which the lac core promoter has been replaced with the lacUV5 core promoter. PCR was used to amplify cgrC and cgrC(L197S) fragments flanked 5′ by an EcoRI site and an N-terminal VSV-G epitope tag and flanked 3′ by a KpnI site. The fragments were digested with EcoRI and KpnI and cloned into pUC18-mini-Tn7-TOPLACUV5 cut with EcoRI and KpnI.

Plasmids for bacterial two-hybrid assays.

Plasmid pBRωGP, which directs the synthesis of an ω-Gal11P fusion protein (9), has been described previously (2), and it can be used to create fusions to the C terminus of the ω subunit of E. coli RNA polymerase (RNAP). Proteins are fused to ω by a short linker sequence of three alanine residues partially specified by a NotI restriction site. Plasmid pBRωGP contains a ColE1 origin of replication, confers resistance to carbenicillin, and carries an IPTG-inducible lacUV5 promoter that drives the expression of the ω fusion protein. Versions of pBRω encoding ω fused to portions of the Cgr proteins were constructed by cloning the appropriate NotI/BamHI-digested PCR products into NotI/BamHI-digested pBRωGP. The resulting plasmids contain genes encoding ω fusion proteins under the control of an IPTG-inducible lacUV5 promoter. Plasmid pBRω-CgrA directs the synthesis of E. coli ω (residues 1 to 90) fused to residues 2 to 408 (the full-length protein) of P. aeruginosa CgrA. Plasmid pBRω-CgrA2-247 directs the synthesis of E. coli ω (residues 1 to 90) fused to residues 2 to 247 of P. aeruginosa CgrA. Plasmid pBRω-CgrA248-408 directs the synthesis of E. coli ω (residues 1 to 90) fused to residues 248 to 408 of P. aeruginosa CgrA. Plasmid pBRω-CgrB directs the synthesis of E. coli ω (residues 1 to 90) fused to residues 2 to 170 of P. aeruginosa CgrB (the full-length protein). Plasmid pBRω-CgrC directs the synthesis of E. coli ω (residues 1 to 90) fused to residues 2 to 211 of P. aeruginosa CgrC (the full-length protein).

Plasmid pACTR-V-Zif-AP encodes V-Zif, the zinc finger DNA-binding domain of the murine Zif268 protein (Zif) with a VSV-G epitope tag fused to its N terminus via a 2-amino-acid linker (Gly-Ser) (2). This plasmid can be used to create fusions to the C terminus of V-Zif via a 4-amino-acid linker (Val-Ala-Ala-Ala) specified in part by a NotI restriction site. Plasmid pACTR-V-Zif-AP confers resistance to tetracycline, contains a p15A origin of replication, and carries an IPTG-inducible lacUV5 promoter that drives the expression of the V-Zif fusion protein. Versions of pACTR-V-Zif encoding V-Zif fused to portions of the Cgr proteins were constructed by cloning the appropriate NotI/BamHI-digested PCR products into NotI/BamHI-digested pACTR-V-Zif-AP. The resulting plasmids encode V-Zif fusion proteins under the control of an IPTG-inducible lacUV5 promoter. Plasmid pACTR-V-Zif-CgrA directs the synthesis of full-length CgrA (residues 2 to 408) fused to the C terminus of V-Zif. Plasmid pACTR-V-Zif-CgrB directs the synthesis of full-length CgrB (residues 2 to 170) fused to the C terminus of V-Zif. Plasmid pACTR-V-Zif-CgrC directs the synthesis of full-length CgrC (residues 2 to 211) fused to the C terminus of V-Zif. Plasmid pACTR-V-Zif-CgrC88-211 directs the synthesis of CgrC residues 88 to 211 fused to the C terminus of V-Zif. Plasmid pACTR-V-Zif-CgrC170-211 directs the synthesis of CgrC residues 170 to 211 fused to the C terminus of V-Zif.

Cgr expression plasmids.

To make expression plasmid pV-CgrC, a DNA fragment containing the P. aeruginosa cgrC coding sequence (PA2126) flanked 5′ by an EcoRI site, a consensus Shine-Dalgarno sequence, and an N-terminal VSV-G epitope tag and flanked 3′ by a HindIII site was generated by PCR, digested with HindIII and EcoRI, and cloned into pPSV37 (16) cut with HindIII and EcoRI. The VSV-G epitope is fused to the N terminus of full-length CgrC (residues 2 to 211) by a 3-amino-acid linker (Ala-Ala-Ala) encoded in part by a NotI restriction site. Plasmid pV-CgrC therefore directs the IPTG-inducible synthesis of V-CgrC and confers resistance to gentamicin. A PCR-amplified DNA fragment encoding CgrC(L197S) (residues 2 to 211) flanked 5′ by a NotI site and 3′ by a EcoRI site was digested with NotI and EcoRI and cloned into pV-CgrC digested with NotI-EcoRI, thereby replacing wild-type cgrC with cgrC(L197S) to create the pV-CgrC(L197S) expression vector.

Plasmids pV-CgrC170-212 and pV-CgrC170-211(L197S) were constructed using PCR to amplify fragments containing the coding sequences of cgrC170-212 and cgrC170-211(L197S) flanked 5′ by an EcoRI site, a consensus Shine-Dalgarno sequence, and an N-terminal VSV-G epitope tag and flanked 3′ by a HindIII site. The appropriate PCR products were digested with HindIII and EcoRI and cloned into pPSV37 cut with HindIII and EcoRI. The VSV-G epitope is fused to the N terminus of each fragment by a 3-amino-acid linker (Ala-Ala-Ala) encoded in part by a NotI restriction site. Plasmids pV-CgrC170-212 and pV-CgrC170-211(L197S) therefore direct the IPTG-inducible synthesis of either CgrC170-212 or CgrC170-211(L197S) and confer resistance to gentamicin.

Plasmid pCgrA-TAP was constructed using overlap PCR to create a fragment encoding residues 1 to 407 of CgrA (the full-length protein minus the stop codon) linked to the full-length sequence of the tandem affinity purification (TAP) tag by a 3-amino-acid linker (Ala-Ala-Ala) encoded in part by a NotI restriction site (32). PCR was used to amplify a version of this fragment that was flanked 5′ by an EcoRI site and a consensus Shine-Dalgarno sequence and flanked 3′ by a HindIII site. The PCR product was digested with HindIII and EcoRI and cloned into pPSV37 (16) cut with HindIII and EcoRI. Plasmid pCgrA-TAP therefore directs the IPTG-inducible synthesis of CgrA-TAP and confers resistance to gentamicin.

Genetic screen to isolate CgrC mutants specifically defective for interaction with CgrA.

The cgrC portion of pBRω-CgrC was randomly mutagenized by PCR (30 cycles) with Taq DNA polymerase. A pool of plasmids encoding the resulting ω-CgrC mutants was transformed into E. coli KDZif1ΔZ cells containing pACTR-V-Zif-CgrA. Transformants were plated on LB agar plates containing kanamycin, carbenicillin, tetracycline, IPTG (50 μM), X-Gal, and the β-galactosidase inhibitor tPEG (250 μM). Colonies exhibiting low lacZ expression relative to that of cells containing a plasmid encoding wild-type pBRω-CgrC were identified. About 50 colonies were picked out of the ∼5,000 colonies examined. Plasmids encoding ω-CgrC mutants were isolated and transformed into E. coli KDZif1ΔZ cells containing pACTR-V-Zif-CgrC. Transformants were plated on LB agar plates containing kanamycin, carbenicillin, tetracycline, IPTG (50 μM), X-Gal, and tPEG (250 μM). Colonies exhibiting similar lacZ expression relative to that of cells containing a plasmid encoding wild-type pBRω-CgrC were identified, and the pBRω-CgrC mutants were isolated. Plasmids identified were retransformed into E. coli KDZif1ΔZ cells containing pACTR-V-Zif-CgrC and assayed for β-galactosidase activity to confirm the phenotypes observed on plates. Plasmids then were transformed into KDZif1ΔZ cells containing pACTR-V-Zif-CgrA and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. Plasmids encoding mutant versions of CgrC that were unable to interact with CgrA but were still able to interact with wild-type CgrC were sequenced.

Bacterial two-hybrid assays.

Cells were grown with aeration at 37°C in LB supplemented with carbenicillin, tetracycline, and IPTG at the concentrations indicated. Cells were permeabilized with SDS-CHCl3, and β-galactosidase activity was assayed as previously described (10). Assays were performed at least three times in duplicate on separate occasions; duplicate measurements differed by <10%. Representative data sets are shown. Values are averages based on one experiment.

P. aeruginosa β-galactosidase assays.

Cells were grown with aeration at 37°C in LB supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics and with IPTG at the concentrations specified. Cells were permeabilized with SDS-CHCl3, and β-galactosidase activity was assayed as described above for the bacterial two-hybrid experiments. Assays were performed at least two times in triplicate on separate occasions. Representative data sets are shown. Values are averages based on three biological replicates from one experiment.

Western blots.

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 4 to 12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen), and Western blotting and protein detection was performed as described previously (5). V-CgrC and V-CgrC(L197S) were detected using an antibody against the VSV-G tag (Sigma-Aldrich). CgrA-CBP was detected using an antibody against calmodulin binding peptide (CBP) (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL). For the experiments shown in Fig. 3, Western blots were probed with an antibody against the α subunit of RNAP (NeoClone) to control for sample loading.

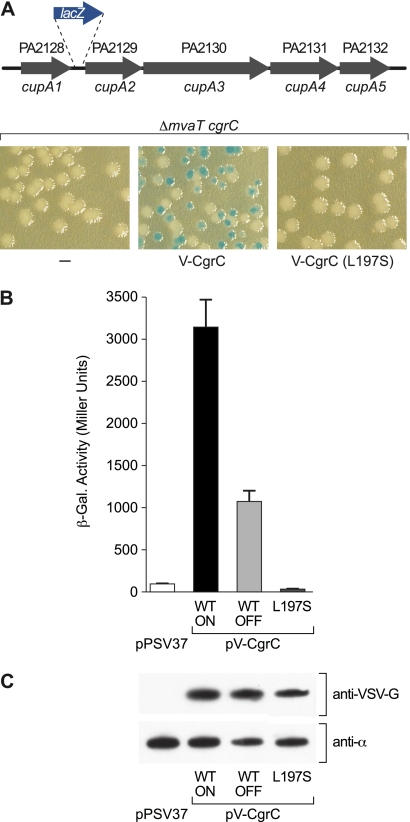

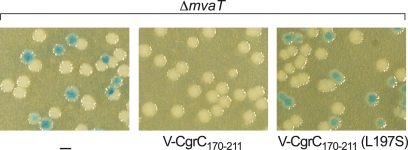

Fig. 3.

Interaction between CgrA and CgrC is required for cupA gene expression. (A) The upper panel is a schematic of the cupA lacZ reporter in strain PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ. The lower panel shows colony phenotypes of PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ cells (indicated ΔmvaT cgrC) harboring the empty control plasmid pPSV37 (indicated by a minus), harboring plasmid pV-CgrC, which directs the IPTG-controlled synthesis of V-CgrC (indicated V-CgrC), or harboring plasmid pV-CgrC(L197S), which directs the IPTG-controlled synthesis of V-CgrC(L197S) [indicated as V-CgrC(L197S)]. Cells were plated on LB agar plates containing X-Gal and IPTG (1 mM) and grown overnight at 37°C. Note that only cells containing pV-CgrC gave rise to phase-ON and phase-OFF colonies. (B) Quantification of cupA lacZ expression in cells of the PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ reporter strain. Cells contained either the empty control vector pPSV37 (white bar), the V-CgrC expression vector pV-CgrC (indicated as WT; black and pale gray bars), or the V-CgrC(L197S) expression vector pV-CgrC(L197S) (indicated as L197S; dark gray bar). Cultures inoculated with phase-ON and phase-OFF colonies are indicated ON and OFF, respectively. Cells were grown in LB containing IPTG (1 mM) and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. (C) The upper panel shows the Western blot analysis of the abundance of V-CgrC and V-CgrC(L197S) using an antibody that recognizes the VSV-G epitope tag. Proteins were from cells used for panel B. The lower panel shows a Western blot of cell lysates probed with an antibody that recognizes the α subunit of RNAP that serves as a control for sample loading.

TAP.

Cells of PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ attTn7::TOPLACUV5-V-cgrC, PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ attTn7::TOPLACUV5-V-cgrC(L197S), or PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ attTn7::TOPLACUV5 were transformed with pCgrA-TAP. PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ attTn7::TOPLACUV5-V-cgrC also was transformed with pPSV37 (empty vector). The resulting transformants were grown at 37°C with aeration in 200 ml of LB containing gentamicin and IPTG (1 mM) to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.5 and then harvested by centrifugation at 4°C. TAP then was performed as described previously (20).

ChIP assays.

Cultures of PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ transformed with pV-CgrC, pV-CgrC(L197S), or pPSV37 (empty vector control) were inoculated in triplicate into LB broth containing gentamicin and IPTG (1 mM), and these cultures were grown at 37°C with aeration for ∼16 h. The cultures were diluted to a starting OD600 of ∼0.05 and grown with aeration to an OD600 of ∼0.5 at 37°C in LB supplemented with gentamicin and IPTG (1 mM). ChIP then was performed with 3 ml of culture by using anti-VSV-G agarose beads (BETHYL Laboratories), and fold enrichment values were measured by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) relative to those for the PA2155 open reading frame (ORF) essentially as described previously (3). Representative data sets are shown. Values are the averages from three biological replicates.

RESULTS

Bacterial two-hybrid analysis of interactions involving the Cgr proteins.

Because CgrA, CgrB, and CgrC all are required for cupA gene expression, we reasoned that these three proteins might function together by interacting with one another. To determine whether this is the case, we used a bacterial two-hybrid assay. This assay is based on the finding that any sufficiently strong interaction between two proteins can activate transcription in Escherichia coli provided one of the interacting proteins is tethered to the DNA by a DNA-binding protein and the other is tethered to a subunit of E. coli RNA polymerase (RNAP) (9, 11). In the version of the assay used here, contact between a protein (or protein domain) fused to the ω subunit of E. coli RNAP and another protein fused to a zinc finger DNA-binding protein (referred to as V-Zif) activates the transcription of a lacZ reporter gene situated downstream of an appropriate test promoter containing a binding site for Zif (2, 32) (Fig. 1A).

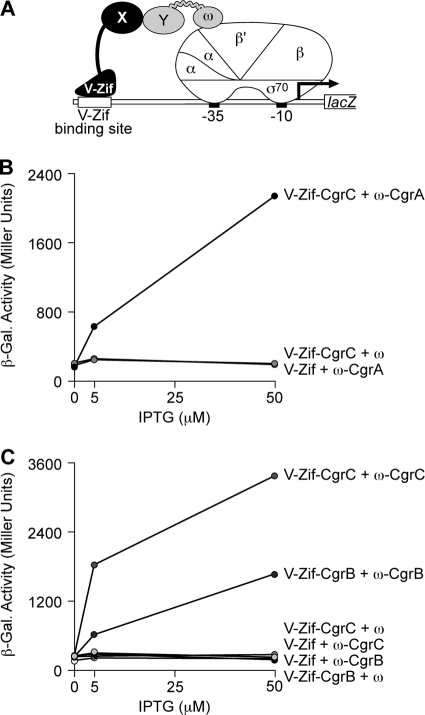

Fig. 1.

Protein-protein interactions involving the Cgr proteins. (A) Schematic of transcription activation-based bacterial two-hybrid system. Contact between proteins X and Y fused to V-Zif and to the ω subunit of E. coli RNAP, respectively, activates transcription from the placZif1-61 test promoter that drives lacZ expression. The placZif1-61 test promoter contains a V-Zif binding site centered 61 bp upstream of the transcription start site of the lac core promoter (whose −10 and −35 elements are indicated). In E. coli reporter strain KDZif1ΔZ, the placZif1-61 test promoter is linked to lacZ and is present on an F′ episome. (B and C) Results of bacterial two-hybrid assays performed with KDZif1ΔZ cells harboring compatible plasmids directing the IPTG-controlled synthesis of the indicated proteins. Cells were grown in the presence of the indicated concentration of IPTG and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. (B) CgrA and CgrC interact with one another. Transcription activation by V-Zif-CgrC in the presence of the ω-CgrA fusion protein. (C) CgrB and CgrC form homomeric complexes. Transcription activation by V-Zif-CgrB in the presence of the ω-CgrB fusion protein and by V-Zif-CgrC in the presence of the ω-CgrC fusion protein.

To test whether CgrA could interact directly with CgrC, we fused full-length CgrC (residues 2 to 211) to the C terminus of V-Zif, and we fused full-length CgrA (residues 2 to 408) to the C terminus of ω. We then determined whether the resulting V-Zif-CgrC fusion protein could activate transcription from a suitable test promoter in cells of an E. coli reporter strain that also synthesized the ω-CgrA fusion protein. Plasmids directing the synthesis of the V-Zif-CgrC and the ω-CgrA fusion proteins were introduced into cells of E. coli strain KDZif1ΔZ, which harbors the placZif1-61 test promoter (depicted in Fig. 1A) linked to lacZ on an F′ episome (32). We found that the V-Zif-CgrC fusion protein strongly activated the transcription of the lacZ reporter (by a factor of ∼11) in cells of the reporter strain that contained the ω-CgrA fusion protein but not in cells that contained wild-type ω (without the fused CgrA moiety) (Fig. 1B). An additional control revealed that V-Zif failed to activate the transcription of the lacZ reporter in the presence of the ω-CgrA fusion protein (Fig. 1B). Analogous experiments performed with a V-Zif-CgrA fusion protein (in which full-length CgrA, residues 2 to 408, is fused to the C terminus of V-Zif) and an ω-CgrC fusion protein (in which full-length CgrC is fused to the C terminus of ω) gave similar results (Fig. 2A). These findings suggest that CgrC and CgrA interact with one another directly.

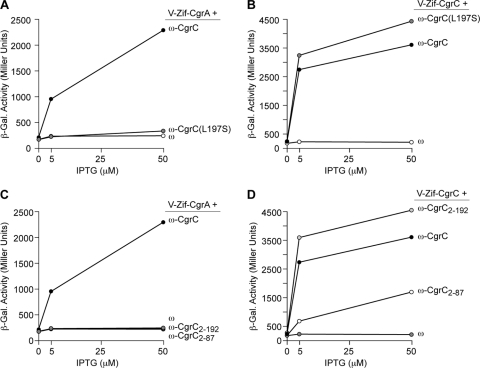

Fig. 2.

Identification of CgrC mutants that are specifically defective for interaction with CgrA. (A to D) Results of bacterial two-hybrid assays performed with KDZif1ΔZ cells harboring compatible plasmids directing the IPTG-controlled synthesis of the indicated proteins. Cells were grown in the presence of the indicated concentration of IPTG and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. (A) Effect of amino acid substitution L197S on the ability of CgrC to interact with CgrA. (B) Effect of amino acid substitution L197S on the ability of CgrC to interact with CgrC. (C) Ability of CgrC2-87 and CgrC2-192 to interact with CgrA. (D) Ability of CgrC2-87 and CgrC2-192 to interact with CgrC.

We next asked whether CgrB interacts with CgrA or CgrC. We therefore fused full-length CgrB (residues 2 to 170) to the C terminus of V-Zif. Bacterial two-hybrid assays performed with cells of the E. coli reporter strain KDZif1ΔZ, synthesizing the resulting V-Zif-CgrB fusion protein in combination with either the ω-CgrA fusion protein or the ω-CgrC fusion protein, failed to reveal any detectable interactions between CgrB and CgrA or between CgrB and CgrC (data not shown).

Both CgrB and CgrC are predicted to belong to protein families whose members typically function as homodimers (CgrB bears homology to members of the GNAT family of acetyl transferases, whereas CgrC bears homology to members of the ParB family). Therefore, we tested whether CgrB or CgrC could participate in homotypic interactions using the bacterial two-hybrid assay. To test whether CgrB could interact with itself, we fused full-length CgrB to the C terminus of ω. Plasmids directing the synthesis of the resulting ω-CgrB fusion protein and the V-Zif-CgrB fusion protein then were introduced into cells of the E. coli reporter strain KDZif1ΔZ. Similarly, to test whether CgrC could interact with itself, plasmids directing the synthesis of the V-Zif-CgrC and ω-CgrC fusion proteins were introduced into KDZif1ΔZ cells. The results depicted in Fig. 1C show that the V-Zif-CgrB fusion protein strongly activated the transcription of the lacZ reporter (by a factor of ∼8) in cells that contained the ω-CgrB fusion protein but not in cells of the reporter strain that contained wild-type ω. Furthermore, we found that the V-Zif-CgrC fusion protein strongly activated the transcription of the lacZ reporter (by a factor of ∼17) in cells that contained the ω-CgrC fusion protein but not in cells containing wild-type ω. These findings suggest that both CgrB and CgrC can interact with themselves. Analogous experiments performed with a V-Zif-CgrA fusion protein and the ω-CgrA fusion protein did not reveal any detectable homotypic interactions of CgrA (data not shown).

Isolation of CgrC mutants specifically defective for interaction with CgrA.

The results of our two-hybrid analyses suggest that CgrA and CgrC regulate the expression of the cupA genes by forming a complex. To test whether this was the case, we first sought to identify mutants of CgrC that were specifically defective for interaction with CgrA. Our strategy for isolating such mutants involved two sequential genetic screening steps, both of which employed our bacterial two-hybrid assay (Fig. 1). In the first screening step we identified mutants of the ω-CgrC fusion protein that failed to interact with the V-Zif-CgrA fusion protein, whereas in the second screening step we identified those ω-CgrC mutants from the first screen that still were capable of interacting with the V-Zif-CgrC fusion protein. With this approach we hoped to identify mutants of CgrC that could no longer interact with CgrA but still could participate in homotypic interactions.

To identify mutants of CgrC that are defective for interaction with CgrA, DNA encoding the CgrC portion of the ω-CgrC fusion protein was mutagenized by the PCR. Plasmids encoding mutant ω-CgrC fusion proteins that failed to activate the transcription of the lacZ reporter in KDZif1ΔZ cells in the presence of the V-Zif-CgrA fusion protein were isolated. We then screened these plasmids for those encoding mutant ω-CgrC fusion proteins that could still activate the transcription of the lacZ reporter gene in cells that synthesized the V-Zif-CgrC fusion protein. With this approach we identified three mutants that were specifically defective for the interaction with CgrA. One of these contained amino acid substitution L197S, whereas the other two mutants were truncated derivates of the ω-CgrC fusion protein containing either residues 2 to 87 or residues 2 to 192 of CgrC. The results depicted in Fig. 2 show that the mutant ω-CgrC fusion protein containing amino acid substitution L197S in CgrC [ω-CgrC(L197S)] no longer detectably interacts with V-Zif-CgrA (Fig. 2A), but it interacts as well as the wild-type ω-CgrC fusion protein with the V-Zif-CgrC fusion protein (Fig. 2B). Moreover, ω-CgrC(L197S) interacted indistinguishably with the wild-type V-Zif-CgrC fusion protein and a V-Zif-CgrC(L197S) mutant fusion protein (data not shown). The results depicted in Fig. 2C and D show that the mutant ω-CgrC fusion proteins containing residues 2 to 87 (ω-CgrC2-87) or residues 2 to 192 of CgrC (ω-CgrC2-192) no longer detectably interact with V-Zif-CgrA but still interact with V-Zif-CgrC. Note, however, that the V-Zif-CgrC fusion protein does not activate transcription from the test promoter in the presence of the ω-CgrC2-87 fusion protein quite as well as it does in the presence of the wild-type ω-CgrC fusion protein, the ω-CgrC(L197S) fusion protein, or the ω-CgrC2-192 fusion protein. Amino acid substitution L197S in CgrC, or the removal of the last 24 amino acids of CgrC, therefore appears to disrupt the interaction with CgrA but has no negative effect on the ability of CgrC to participate in homotypic interactions. Although the removal of the last 124 residues of CgrC disrupts the interaction with CgrA, this also appears to influence the ability of CgrC to form homomers.

Interaction between CgrA and CgrC is required for cupA gene expression.

We next sought to determine whether the interaction between CgrA and CgrC is important for cupA expression. To do this, we made use of the CgrC (L197S) mutant, which is specifically deficient for the interaction with CgrA, and asked whether this mutant could complement the effects of a cgrC deletion.

We have shown previously that in P. aeruginosa the cupA fimbrial genes are expressed in a phase-variable manner in cells that lack the H-NS family member MvaT (i.e., in cells of a ΔmvaT mutant) (33). Specifically, we have shown that in reporter strain PAO1 ΔmvaT cupA lacZ, in which lacZ is positioned between the cupA1 and cupA2 genes on the PAO1 chromosome (Fig. 3A), the phase-variable expression of the cupA genes gives rise to both blue and white colonies on LB agar plates containing X-Gal (32). Furthermore, we have shown that the phase-variable expression of the cupA genes that occurs in a ΔmvaT mutant background is dependent upon cgrC (as well as cgrA and cgrB) (33). Therefore, to address whether CgrC(L197S) can complement the effects of a cgrC mutation, we asked whether the mutant protein could restore the phase-variable expression of the cupA genes in cells of a ΔmvaT mutant strain that lacked a functional cgrC gene. Plasmids directing the synthesis of versions of either wild-type CgrC or CgrC(L197S), each containing a VSV-G epitope at its N terminus, were introduced into cells of reporter strain PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ. Wild-type CgrC containing a VSV-G tag at its N terminus (V-CgrC) could complement the effect of the cgrC mutation and restored the phase-variable expression of the cupA genes to the ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ reporter strain (Fig. 3A and B). However, unlike the wild-type version of the protein, the V-CgrC(L197S) mutant failed to complement the cgrC mutation. Western blotting using an antibody against the VSV-G epitope tag revealed that comparable amounts of V-CgrC and V-CgrC(L197S) were present in cells of the reporter strain (Fig. 3C). These findings suggest that interaction between CgrC and CgrA is required for the cupA genes to be expressed in a phase-variable manner.

CgrC, but not CgrC(L197S), copurifies with CgrA-TAP.

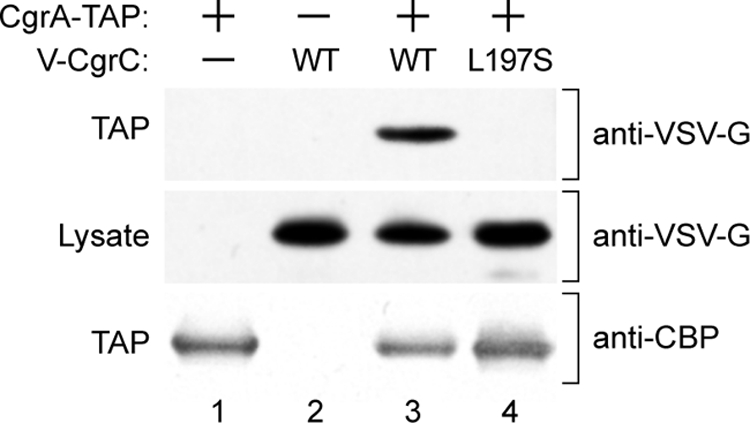

To test explicitly the prediction that amino acid substitution L197S in CgrC disrupted the CgrC-CgrA interaction in cells of P. aeruginosa, we compared the abilities of V-CgrC and V-CgrC(L197S) to copurify with a version of CgrA that contains a tandem affinity purification (TAP) tag at its C terminus (CgrA-TAP) (21, 32); note that the presence of the TAP tag does not appear to impair the function of CgrA, as CgrA-TAP can complement the effect of a cgrA mutation (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). To do this, we constructed two different strains of P. aeruginosa, both of which were derived from our PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ reporter strain. The first of these (PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ attTn7::TOPLACUV5-V-cgrC) contained the gene encoding V-CgrC under the control of an IPTG-regulated promoter located at the Tn7 attachment site on the PAO1 chromosome. The second strain [PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ attTn7::TOPLACUV5-V-cgrC(L197S)] contained the gene encoding V-CgrC(L197S) under the control of an IPTG-regulated promoter at the PAO1 Tn7 attachment site. As anticipated, V-CgrC supplied ectopically from the Tn7 attachment site complemented the cgrC mutation present in the reporter strain, giving rise to both blue and white colonies on X-Gal plates, whereas V-CgrC(L197S) did not (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). A plasmid encoding CgrA-TAP under the control of an IPTG-inducible promoter was introduced into cells of each of these strains and into cells of the parental PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ control strain (that does not synthesize any VSV-G-tagged version of CgrC). As an additional control, an empty vector (that does not encode CgrA-TAP) was introduced into the strain that synthesizes V-CgrC.

Cells were grown to mid-log phase, and CgrA (together with any associated proteins) was purified by TAP. Cell lysates and proteins purified by TAP then were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the amount of CgrA and CgrC present in each sample was determined by Western blotting. The results depicted in Fig. 4 show that wild-type V-CgrC copurifies with CgrA-TAP but that V-CgrC(L197S) does not, despite there being similar amounts of each of the two proteins and similar amounts of CgrA-TAP present in the cells used for TAP. (Note that following TAP, only the calmodulin binding peptide [CBP] moiety of the TAP tag remains fused to CgrA.) These findings demonstrate that amino acid substitution L197S in CgrC disrupts the interaction between CgrC and CgrA in cells of P. aeruginosa.

Fig. 4.

CgrC copurifies with CgrA-TAP, whereas CgrC(L197S) does not. V-CgrC and V-CgrC(L197S) were ectopically expressed in cells producing CgrA-TAP. Following TAP, proteins that copurified with CgrA-TAP were separated on a 4 to 12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gel, and the presence of V-CgrC and V-CgrC(L197S) was analyzed by Western blotting. Proteins present in the cell lysates prior to TAP were separated and analyzed in the same manner. Upper and middle panels show V-CgrC and V-CgrC(L197S) present following TAP (upper) and in cell lysates prior to TAP (middle). The lower panel shows CBP-tagged CgrA present following TAP. Because the protein A moieties of the TAP tag are removed during the affinity purification procedure, the CBP portion of the TAP tag is all that remains on CgrA following TAP. Lane 1, PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ cells containing plasmid pCgrA-TAP (cells therefore synthesize CgrA-TAP). Lane 2, PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ attTn7::TOPLACUV5-V-cgrC cells containing the empty control plasmid pPSV37 (cells therefore synthesize V-CgrC). Lane 3, PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ attTn7::TOPLACUV5-V-cgrC cells containing plasmid pCgrA-TAP (cells therefore synthesize both CgrA-TAP and V-CgrC). Lane 4, PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ attTn7::TOPLACUV5-V-cgrC(L197S) cells containing plasmid pCgrA-TAP [cells therefore synthesize both CgrA-TAP and V-CgrC(L197S)].

Both CgrC and CgrC(L197S) associate with the cupA promoter region.

Because CgrC is a putative DNA-binding protein, we hypothesized that CgrC influences cupA gene expression by binding directly to the cupA promoter region. To begin to test this hypothesis, we therefore asked whether we could detect the association of CgrC with the cupA promoter in cells of P. aeruginosa using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP).

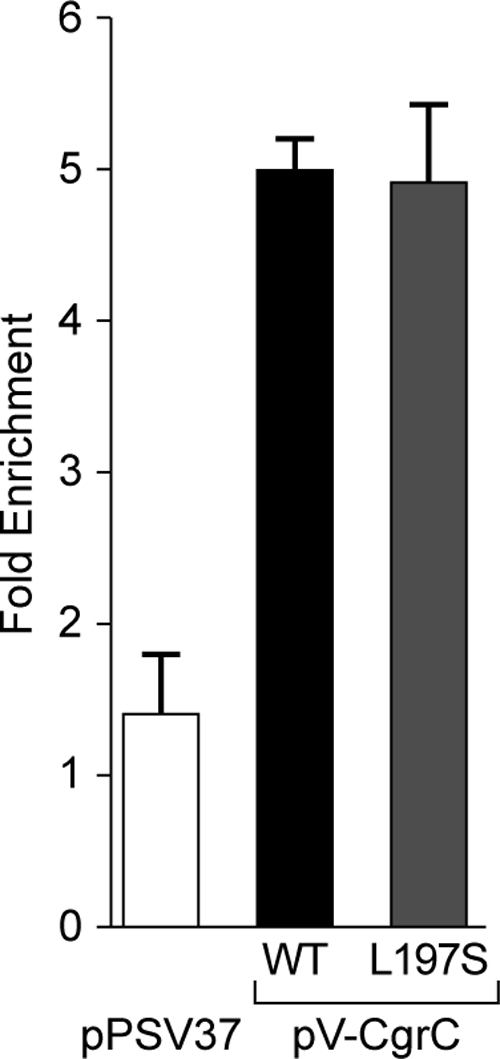

A plasmid directing the synthesis of V-CgrC was introduced into cells of reporter strain PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ. Cells from a resulting phase-ON colony were grown to the mid-logarithmic phase of growth alongside cells of the reporter strain that contained an empty vector (and therefore did not synthesize any V-CgrC). Following ChIP, the degree of enrichment of the cupA promoter relative to that of a control region of the chromosome (i.e., one not expected to be bound by CgrC) was determined by qPCR. Whereas the enrichment for the cupA promoter was ∼5-fold in the presence of V-CgrC, it was ∼1.4-fold in the absence of V-CgrC (Fig. 5). Note that similar results were obtained for V-CgrC with cells isolated from a phase-OFF colony (data not shown). These findings suggest that CgrC associates with the cupA promoter region.

Fig. 5.

CgrC and CgrC(L197S) associate with the cupA promoter region. ChIP of V-CgrC and V-CgrC(L197S) in PAO1 ΔmvaT cgrC cupA lacZ cells containing the indicated plasmids is shown. ChIP-enriched DNA was measured by qPCR, and the fold enrichment of the cupA promoter was determined by comparison with the PA2155 ORF as a nonbinding control. Error bars represent 1 standard deviation from the mean fold enrichment.

We next asked whether the interaction between CgrC and CgrA was required for CgrC to associate with the cupA promoter. ChIP experiments performed with cells of the reporter strain that synthesized V-CgrC(L197S) revealed that V-CgrC(L197S) associated with the cupA promoter (with enrichment of ∼5-fold) to an extent similar to that of wild-type V-CgrC. These findings suggest that CgrC can associate with the cupA promoter regardless of whether or not it interacts with CgrA. Furthermore, these findings rule out the formal possibility that the V-CgrC(L197S) mutant cannot complement a cgrC mutation because it can no longer associate with the DNA.

Defining the regions of CgrC and CgrA involved in formation of the CgrA-CgrC complex.

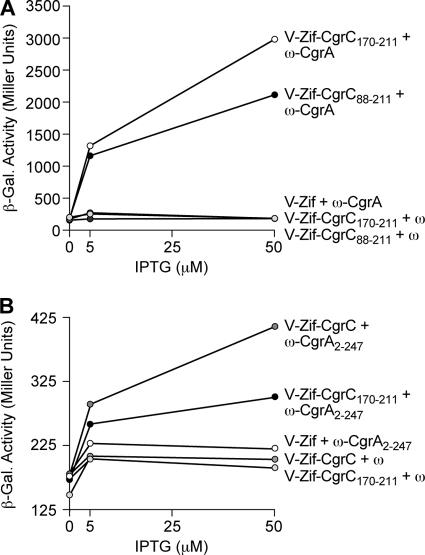

To define the minimal region of CgrC that is capable of interacting with CgrA and to determine which portion of CgrA interacts with CgrC, we used our bacterial two-hybrid system. We first fused different C-terminal portions of CgrC to V-Zif and then asked which of these fusion proteins could activate the transcription of the lacZ reporter in cells of strain KDZif1ΔZ in the presence of the ω-CgrA fusion protein. V-Zif-CgrC fusion proteins harboring residues 88 to 211 of CgrC (V-Zif-CgrC88-211) or residues 170 to 211 of CgrC (V-Zif-CgrC170-211) activated the transcription of the lacZ reporter in the presence of the ω-CgrA fusion protein but not in the presence of wild-type ω (Fig. 6A). Therefore, the C-terminal portion of CgrC encompassing residues 170 to 211 appears to be sufficient for interaction with CgrA.

Fig. 6.

C-terminal portion of CgrC interacts with the N-terminal portion of CgrA. (A and B) Results of bacterial two-hybrid assays performed with KDZif1ΔZ cells harboring compatible plasmids directing the IPTG-controlled synthesis of the indicated proteins. Cells were grown in the presence of the indicated concentration of IPTG and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. (A) CgrC88-211 and CgrC170-211 interact with full-length CgrA. Transcription activation by V-Zif-CgrC88-211 and by V-Zif-CgrC170-211 in the presence of the ω-CgrA fusion protein is shown. (B) Full-length CgrC and CgrC170-211 interact with CgrA2-247. Transcription activation by V-Zif-CgrC and by V-Zif-CgrC170-211 in the presence of the ω-CgrA2-247 fusion protein is shown.

CgrA is predicted to contain a putative PAPS reductase domain (residues 28 to 247) and to contain a second domain of unknown function (residues 248 to 408). To determine which of these putative domains of CgrA are involved in the interaction with CgrC, we made two additional fusion proteins. One of these comprised residues 2 to 247 of CgrA fused to the C terminus of ω (ω-CgrA2-247), whereas the other comprised residues 248 to 408 of CgrA fused to the C terminus of ω (ω-CgrA248-408). In support of the idea that the region of CgrA containing the putative PAPS reductase domain is involved in the interaction with CgrC, both the V-Zif-CgrC and V-Zif-CgrC170-211 fusion proteins activated the transcription of the lacZ reporter in the presence of the ω-CgrA2-247 fusion protein (Fig. 6B). There was no detectable interaction between the ω-CgrA248-408 fusion protein and either the V-Zif-CgrC or the V-Zif-CgrC170-211 fusion protein (data not shown), although we do not know whether the ω-CgrA248-408 fusion protein is stable. Our findings with the ω-CgrA2-247 fusion protein suggest that some or all of the CgrC interaction determinants are contained within the portion of CgrA that includes the putative PAPS reductase domain.

The C-terminal portion of CgrC exerts a dominant-negative phenotype.

Having defined a minimal portion of CgrC that can interact with CgrA using bacterial two-hybrid analyses, we wanted to test whether this same region of CgrC could interact with CgrA in cells of P. aeruginosa. To do this, we tested whether the production of this fragment of CgrC in P. aeruginosa cells would result in a dominant-negative effect on cupA gene expression due to its ability to sequester CgrA in a complex that is incapable of interacting with wild-type CgrC. Accordingly, we introduced a vector directing the synthesis of residues 170 to 211 of CgrC with an N-terminal VSV-G tag (V-CgrC170-211) into cells of our PAO1 ΔmvaT cupA lacZ strain that ordinarily express the cupA genes in a phase-variable manner (32). The ectopic synthesis of V-CgrC170-211 repressed the phase-variable expression of the cupA fimbrial genes, suggesting that this fragment of CgrC can interact with and sequester CgrA in cells of P. aeruginosa (Fig. 7). Consistently with this idea, the ectopic synthesis of a mutant version of V-CgrC170-211 containing amino acid substitution L197S (that would be predicted to be incapable of interacting with CgrA) failed to exert any dominant-negative effect on cupA gene expression in cells of the PAO1 ΔmvaT cupA lacZ reporter strain (Fig. 7). Note that although CgrC interacts with itself, this interaction is mediated by residues that lie N terminal to residue 197 (wholly or partially contained within the fragment of residues 2 to 87 [Fig. 2D]). No appreciable interaction between CgrC170-211 and full-length CgrC (or CgrC170-211) could be detected using our bacterial two-hybrid system (data not shown). Taken together, our findings suggest that the dominant-negative effect of ectopically synthesizing V-CgrC170-211 is due to the sequestration of the CgrC interaction surface on CgrA.

Fig. 7.

Dominant-negative effect of CgrC170-211. PAO1 ΔmvaT cupA lacZ cells (indicated as ΔmvaT) containing either the empty control vector pPSV37 (indicated as a minus), pV-CgrC170-211 (indicated as V-CgrC170-211), or pV-CgrC170-211(L197S) [indicated as CgrC170-211(L197S)] were plated on LB agar plates containing X-Gal and IPTG (5 mM) and grown overnight at 37°C.

DISCUSSION

We have found that the CgrA and CgrC proteins from P. aeruginosa interact with one another directly. We have identified a mutant of CgrC that is specifically defective for interaction with CgrA and found that, unlike the wild-type protein, this mutant cannot restore the phase-variable expression of the cupA genes to cells of a cgrC mutant strain. We also have found that CgrC associates with the cupA promoter regardless of whether or not it interacts with CgrA. Our findings establish that interaction between CgrA and CgrC is required for the phase-variable expression of the cupA fimbrial genes. Furthermore, our findings suggest that CgrC exerts its regulatory effects directly at the cupA promoter, possibly by recruiting CgrA.

The cgrA and cgrC genes originally were identified in a genetic screen for positive regulators of cupA gene expression (33). Both of these genes are essential for the phase-variable expression of the cupA genes that occurs either in wild-type cells grown under anaerobic conditions or in ΔmvaT mutant cells grown aerobically (33). Neither CgrA nor CgrC resembles any classical transcription regulator. CgrA is predicted to be a member of the adenine nucleotide α-hydrolase superfamily of proteins and contains a putative PAPS reductase domain (24, 33), whereas CgrC is predicted to be a member of the ParB protein family (33). ParB family members bind the DNA in a site-specific fashion, typically using a helix-turn-helix motif, and often are involved in DNA segregation (25). Although ParB family members can influence gene expression, they typically function as repressors (4, 17, 19, 22), and there is only one well-characterized example of a ParB-like protein that positively regulates gene expression (28). We have found, using a combination of genetic and biochemical approaches, that the CgrC and CgrA proteins interact with one another, and that this interaction is required for the phase-variable expression of the cupA genes. This interaction involves the C-terminal portion of CgrC (residues 170 to 211) that carries the putative helix-turn-helix motif and the N-terminal portion of CgrA (residues 1 to 208) that carries the putative PAPS reductase domain.

Members of the ParB family of proteins often work in conjunction with other proteins, with the ParB family member typically serving to recruit a protein (or proteins) to a specific location on the DNA through direct protein-protein interactions (1, 12, 27). Because CgrA does not contain any obvious DNA-binding motif, and because CgrC interacts with CgrA and associates with the cupA promoter, we propose that one role of the interaction between CgrC and CgrA is to recruit CgrA to the cupA promoter region. However, ChIP experiments performed with CgrA-TAP did not reveal any detectable association between CgrA and the cupA promoter region (data not shown). It is therefore possible that, rather than serving to recruit CgrA to the promoter, the interaction between CgrC and CgrA modifies the activity of CgrC. Nevertheless, our ChIP experiments suggest that the interaction between CgrC and CgrA does not influence the ability of CgrC to associate with the DNA. Regardless of how the interaction between CgrC and CgrA promotes the expression of the cupA genes, our findings concerning the functional interaction between CgrC and CgrA explain the genetic requirement for both the cgrC and cgrA genes for the phase-variable expression of the cupA fimbrial genes.

Our results with the CgrC(L197S) mutant, which is specifically defective for interaction with CgrA, demonstrate that the phase-variable expression of the cupA genes is dependent upon the interaction between CgrC and CgrA. However, we do not yet know the mechanism governing the phase-variable expression of the cupA genes. We consider two possible roles for the Cgr proteins that are consistent with our data. On the one hand, they may be required for the expression of the cupA genes when cells are in the phase-ON expression state. On the other hand, they may somehow mediate the switch between the different (ON and OFF) cupA expression states without being required for the maintenance of the phase-ON expression state once it has been established. Regardless of whether the interaction between CgrC and CgrA is required for the maintenance of the phase-ON expression state, for the switch between expression states, or both, our findings clearly establish the importance of the interaction between CgrC and CgrA for cupA gene expression.

In addition to cgrA and cgrC, the cgrB gene, which encodes a putative acetyltransferase belonging to the GNAT family (34), also is required for the phase-variable expression of the cupA genes (33). Because we could detect the interaction between CgrA and CgrC in our bacterial two-hybrid assay in which CgrB is absent, we do not think that the interaction between CgrA and CgrC is dependent upon CgrB. (Note also that the E. coli reporter strain used for our two-hybrid assays does not encode any obvious ortholog of CgrB.) Using our bacterial two-hybrid assay, we did not find any detectable interactions between CgrB and CgrA or between CgrB and CgrC, although this does not rule out the possibility that such interactions occur. The fact that we could detect the ability of CgrB to form homomers at least suggests that our inability to detect any heterotypic interactions of CgrB is not simply because the CgrB fusion proteins used in our two-hybrid assays are misfolded. Because all three of the cgr genes are required for the phase-variable expression of the cupA genes, it is conceivable that CgrB interacts with the CgrA-CgrC complex, although additional experiments will be required to test this possibility.

Orthologs of CgrA and CgrC are evident in many different bacteria. The multigenome alignment tool EcoCyc identified CgrA/CgrC pairs in strains of 32 different bacterial species, both Gram-negative and Gram-positive (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The genes encoding them often are found immediately adjacent to or overlapping one another, unlike the situation in P. aeruginosa (where part of the cgrB gene separates cgrA from cgrC) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In addition, several E. coli and Salmonella enterica strains encode more than one set of CgrA and CgrC orthologs. Certain CgrA and CgrC orthologs appear to play important regulatory roles, albeit through mechanisms that are not understood. Indeed, the founding members of this family of coregulators are the IbrA and IbrB proteins, orthologs of CgrA and CgrC, respectively, which are thought to positively coregulate the expression of the prophage-associated eib genes in E. coli strain ECOR-9, which encode immunoglobulin-binding proteins (23). Furthermore, the CgrA homolog from Salmonella enteritidis (annotated YbdN) has been shown to play an important role in biofilm formation in this organism (8). Genes encoding CgrB orthologs are not always found associated with those encoding CgrA and CgrC orthologs. It therefore is possible that in some organisms, orthologs of CgrA and CgrC exert their regulatory effects without the need for a CgrB ortholog, or that the gene encoding the CgrB ortholog resides elsewhere in the genome. Because the regions of CgrA and CgrC we have identified here as interacting with one another are highly conserved among related proteins in other bacteria (see Fig. S3 and S4 in the supplemental material), we think it likely that CgrA and CgrC orthologs present in other bacteria will function coordinately through an analogous direct protein-protein interaction. The widespread existence of orthologs of the cgr genes suggests that our studies of the Cgr proteins from P. aeruginosa will provide mechanistic insight into how Cgr-related proteins exert their regulatory effects in other organisms.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Arne Rietsch (Case Western Reserve University) and Herbert Schweizer (Colorado State University) for plasmids, Renate Hellmiss for artwork, Keith Turner for making the pUC18-mini-Tn7T-TOPLACUV5 plasmid, and Ann Hochschild (Harvard Medical School) for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI069007 (to S.L.D.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 16 September 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bowman G. R., et al. 2008. A polymeric protein anchors the chromosomal origin/ParB complex at a bacterial cell pole. Cell 134:945–955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Castang S., Dove S. L. 2010. High-order oligomerization is required for the function of the H-NS family member MvaT in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 78:916–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Castang S., McManus H. R., Turner K. H., Dove S. L. 2008. H-NS family members function coordinately in an opportunistic pathogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:18947–18952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cervin M. A., et al. 1998. A negative regulator linking chromosome segregation to developmental transcription in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 29:85–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Charity J. C., Blalock L. T., Costante-Hamm M. M., Kasper D. L., Dove S. L. 2009. Small molecule control of virulence gene expression in Francisella tularensis. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Choi K. H., et al. 2005. A Tn7-based broad-range bacterial cloning and expression system. Nat. Methods 2:443–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Costerton J. W., Stewart P. S., Greenberg E. P. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284:1318–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dong H., Zhang X., Pan Z., Peng D., Liu X. 2008. Identification of genes for biofilm formation in a Salmonella enteritidis strain by transposon mutagenesis. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao 48:869–873 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dove S. L., Hochschild A. 1998. Conversion of the ω subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase into a transcriptional activator or an activation target. Genes Dev. 12:745–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dove S. L., Hochschild A. 2004. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on transcription activation. Methods Mol. Biol. 261:231–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dove S. L., Joung J. K., Hochschild A. 1997. Activation of prokaryotic transcription through arbitrary protein-protein contacts. Nature 386:627–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ebersbach G., Briegel A., Jensen G. J., Jacobs-Wagner C. 2008. A self-associating protein critical for chromosome attachment, division, and polar organization in Caulobacter. Cell 134:956–968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Govan J. R. W., Deretic V. 1996. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol. Rev. 60:539–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hayes F., Barilla D. 2006. Assembling the bacterial segrosome. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31:247–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kulasekara H. D., et al. 2005. A novel two-component system controls the expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa fimbrial cup genes. Mol. Microbiol. 55:368–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee P.-C., Stopford C. M., Svenson A. G., Rietsch A. 2010. Control of effector export by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion proteins PcrG and PcrV. Mol. Microbiol. 75:924–941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lynch A. S., Wang J. C. 1995. SopB protein-mediated silencing of genes linked to the sopC locus of Escherichia coli F plasmid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:1896–1900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meissner A., et al. 2007. Pseudomonas aeruginosa cupA-encoded fimbriae expression is regulated by a GGDEF and EAL domain-dependent modulation of the intracellular level of cyclic diguanylate. Environ. Microbiol. 9:2475–2485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Quisel J. D., Grossman A. D. 2000. Control of sporulation gene expression in Bacillus subtilis by the chromosome partioning proteins Soj (ParA) and Spo0J (ParB). J. Bacteriol. 182:3446–3451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rietsch A., Vallet-Gely I., Dove S. L., Mekalanos J. J. 2005. ExsE, a secreted regulator of type III secretion genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:8006–8011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rigaut G., et al. 1999. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat. Biotechnol. 17:1030–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rodionov O., Lobocka M., Yarmolinsky M. 1999. Silencing of genes flanking the P1 plasmid centromere. Science 283:546–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sandt C. H., Hopper J. E., Hill C. W. 2002. Activation of prophage eib genes for immunoglobulin-binding proteins by genes from the IbrAB genetic island of Escherichia coli ECOR-9. J. Bacteriol. 184:3640–3648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Savage H., Montoya G., Svensson C., Schwenn J. D., Sinning I. 1997. Crystal structure of phosphoadenylyl sulphate (PAPS) reductase: a new family of adenine nucleotide α hydrolases. Structure 5:895–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schumacher M. A. 2007. Structural biology of plasmid segregation proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 17:103–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Singh P. K., et al. 2000. Quorum-sensing signals indicate that cystic fibrosis lungs are infected with bacterial biofilms. Nature 407:762–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thanbichler M., Shapiro L. 2006. MipZ, a spatial regulator coordinating chromosome segregation with cell division in Caulobacter. Cell 126:147–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Turner E. C., Dorman C. J. 2007. H-NS antagonism in Shigella flexneri by VirB, a virulence gene transcription regulator that is closely related to plasmid partition factors. J. Bacteriol. 189:3403–3413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Turner K. H., Vallet-Gely I., Dove S. L. 2009. Epigenetic control of virulence gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by a LysR-type transcription regulator. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vallet I., Olson J. W., Lory S., Lazdunski A., Filloux A. 2001. The chaperone/usher pathways of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: identification of fimbrial gene clusters (cup) and their involvement in biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:6911–6916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vallet I., et al. 2004. Biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: fimbrial cup gene clusters are controlled by the transcriptional regulator MvaT. J. Bacteriol. 186:2880–2890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vallet-Gely I., Donovan K. E., Fang R., Joung J. K., Dove S. L. 2005. Repression of phase-variable cup gene expression by H-NS-like proteins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:11082–11087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vallet-Gely I., Sharp J. S., Dove S. L. 2007. Local and global regulators linking anaerobiosis to cupA fimbrial gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 189:8667–8676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vetting M. W., et al. 2005. Structure and functions of the GNAT superfamily of acetyltransferases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 433:212–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Winstanley C., et al. 2009. Newly introduced genomic prophage islands are critical determinants of in vivo competitiveness in the Liverpool epidemic strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Genome Res. 19:12–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Worlitzsch D., et al. 2002. Effects of reduced mucus oxygen concentration in airway Pseudomonas infections of cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Investig. 109:317–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yoon S. S., et al. 2002. Pseudomonas aeruginosa anaerobic respiration in biofilms: relationships to cystic fibrosis pathogenesis. Dev. Cell 3:593–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.