Abstract

In higher eukaryotes, increasing evidence suggests, gene expression is to a large degree controlled by RNA. Regulatory RNAs have been implicated in the management of neuronal function and plasticity in mammalian brains. However, much of the molecular-mechanistic framework that enables neuronal regulatory RNAs to control gene expression remains poorly understood. Here, we establish molecular mechanisms that underlie the regulatory capacity of neuronal BC RNAs in the translational control of gene expression. We report that regulatory BC RNAs employ a two-pronged approach in translational control. One of two distinct repression mechanisms is mediated by C-loop motifs in BC RNA 3′ stem-loop domains. These C-loops bind to eIF4B and prevent the factor's interaction with 18S rRNA of the small ribosomal subunit. In the second mechanism, the central A-rich domains of BC RNAs target eIF4A, specifically inhibiting its RNA helicase activity. Thus, BC RNAs repress translation initiation in a bimodal mechanistic approach. As BC RNA functionality has evolved independently in rodent and primate lineages, our data suggest that BC RNA translational control was necessitated and implemented during mammalian phylogenetic development of complex neural systems.

INTRODUCTION

Translational control is an important means for the regulation of gene expression in eukaryotic cells (22). In neurons, the local translation of select mRNAs in synaptodendritic domains is considered a key determinant of neuronal function and plasticity (11, 13, 28, 42). Strict control of local translation is essential to ensure that relevant proteins are synthesized only when and where needed (11). Progress has been made over the last 10 years as translational control mechanisms have been investigated in neurons, and several translational regulators have been identified (33, 46). In one of these mechanisms, the effectors of neuronal translational control are regulatory BC RNAs (2, 8, 43–45).

Dendritic BC RNAs, neuronal small cytoplasmic RNAs (scRNAs) that include rodent BC1 RNA and primate BC200 RNA (20, 21, 40, 41), are non-protein-coding RNAs that regulate translation at the level of initiation (43, 44). Translational control mediated by BC1 RNA is important in the management of neuronal excitability (8, 47, 48). Lack of BC1 RNA in a BC1−/− animal model triggers increased group I metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent synthesis of select synaptic proteins (47). Such alterations in the absence of BC1 RNA precipitate neuronal metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated hyperexcitability that manifests in the form of exaggerated cortical gamma frequency oscillations, epileptogenic neuronal responses, and generalized seizures triggered by auditory stimulation (47, 48). These phenotypical manifestations are consonant with the molecular role of BC RNAs as translational repressors. BC1 RNA inhibits recruitment of the 43S preinitiation complex to the mRNA (44), a rate-limiting step in translation initiation that is mediated by the eIF4 family of eukaryotic initiation factors (6, 9, 12, 31).

The eIF4 family of factors includes eIF4E, a cap-binding protein that interacts with the 5′ ends of mRNAs, eIF4A, an ATP-dependent helicase that unwinds double-stranded elements in mRNA 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs), eIF4B, a multifunctional factor that stimulates eIF4A activity and mediates recruitment of the 43S preinitiation complex, and eIF4G, a large scaffold protein that binds eIF4E, eIF4A, eIF3, and poly(A) binding protein (PABP) (5, 6, 9, 31). The concerted activities of eIFs 4E, 4A, and 4G, which together form the heterotrimeric complex eIF4F, eIF4B, and PABP appear to mediate recruitment of the 43S complex to the 5′ end of the mRNA (31).

Previous work has shown that BC RNAs interact with eIF4A and PABP (14, 43, 44). While interactions with PABP seem to play only a minor role in translational repression mediated by BC1 RNA, interactions with eIF4A result in repression of the factor's helicase activity (19). Recently, BC1 RNA was also shown by UV cross-linking to interact with eIF4B (19), but the functional relevance of this interaction was not examined. A key question therefore arises: how do interactions with eIFs 4A and 4B result in translational repression by neuronal BC RNAs? We now report that BC RNAs employ a novel, bimodal mechanism in translational control. Our data reveal that two separate BC RNA structural domains interact with eIF4A and eIF4B, respectively, and repress translation by targeting two distinct initiation requirements: eIF4B's interaction with ribosomal 18S rRNA and eIF4A's catalytic activity. Thus, regulatory BC RNAs exert translational repression competence via a dual mode of action.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Constructs and RNAs.

Murine 18S rRNA was amplified by RT-PCR and cloned into the pGEM-T easy vector (Promega). Primers were designed as previously described (27) and are as follows: 18S rRNAT7_1 forward, TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGACCTGGTTGATCCTGCCAGT, and reverse, TAATGATCCTTCCGCAGGTTCACCTACGG.

BC RNA mutations were generated using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) or, alternatively, were commercially generated (Genscript). The following BC RNAs and BC RNA derivatives were used (mutations are indicated in boldface): wild-type (WT) BC1 RNA, GGGGUUGGGGAUUUAGCUCAGUGGUAGAGCGCUUGCCUAGCAAGCGCAAGGCCCUGGGUUCGGUCCUCAGCUCCGAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGACAAAAUAACAAAAAGACCAAAAAAAAACAAGGUAACUGGCACACACAACCUUU; BC1 RNA mutant WC, GGGGUUGGGGAUUUAGCUCAGUGGUAGAGCGCUUGCCUAGCAAGCGCAAGGCCCUGGGUUCGGUCCUCAGCUCCGAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGACAAAAUAACAAAAAGACCAAAAAAAAACAAGGUAACUGGCACACAGUUACCUUU; BC1 RNA mutant Loop, GGGGUUGGGGAUUUAGCUCAGUGGUAGAGCGCUUGCCUAGCAAGCGCAAGGCCCUGGGUUCGGUCCUCAGCUCCGAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGACAAAAUAACAAAAAGACCAAAAAAAAACAAGGUGUAUGGCACACACAACCUUU; BC1 RNA mutant A-U, GGGGUUGGGGAUUUAGCUCAGUGGUAGAGCGCUUGCCUAGCAAGCGCAAGGCCCUGGGUUCGGUCCUCAGCUCCGAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGACAAAAUAACAAAAAGACCAAAAAAAAACAAGGAAACAGGCACACUCAUCCUUU; BC1 RNA mutant U+, GGGGUUGGGGAUUUAGCUCAGUGGUAGAGCGCUUGCCUAGCAAGCGCAAGGCCCUGGGUUCGGUCCUCAGCUCCUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUCUCUUUAUUUCUUUCUUUAUUUUUUUUGUUAACAAGGUAACUGGCACACACAACCUUU; WT BC200 RNA, GGCCGGGCGCGGUGGCUCACGCCUGUAAUCCCAGCUCUCAGGGAGGCUAAGAGGCGGGAGGAUAGCUUGAGCCCAGGAGUUCGAGACCUGCCUGGGCAAUAUAGCGAGACCCCGUUCUCCAGAAAAAGGAAAAAAAAAAACAAAAGACAAAAAAAAAAUAAGCGUAACUUCCCUCAAAGCAACAACCCCCCCCCCCCUUU; BC200 RNA mutant WC, GGCCGGGCGCGGUGGCUCACGCCUGUAAUCCCAGCUCUCAGGGAGGCUAAGAGGCGGGAGGAUAGCUUGAGCCCAGGAGUUCGAGACCUGCCUGGGCAAUAUAGCGAGACCCCGUUCUCCAGAAAAAGGAAAAAAAAAAACAAAAGACAAAAAAAAAAUAAGCGUAACUUCCCUCAAAGCAAGUUACCCCCCCCCCCCUUU; BC200 RNA mutant Loop, GGCCGGGCGCGGUGGCUCACGCCUGUAAUCCCAGCUCUCAGGGAGGCUAAGAGGCGGGAGGAUAGCUUGAGCCCAGGAGUUCGAGACCUGCCUGGGCAAUAUAGCGAGACCCCGUUCUCCAGAAAAAGGAAAAAAAAAAACAAAAGACAAAAAAAAAAUAAGCGUGUAUUCCCUCAAAGCAACAACCCCCCCCCCCCUUU; BC200 RNA mutant A-U, GGCCGGGCGCGGUGGCUCACGCCUGUAAUCCCAGCUCUCAGGGAGGCUAAGAGGCGGGAGGAUAGCUUGAGCCCAGGAGUUCGAGACCUGCCUGGGCAAUAUAGCGAGACCCCGUUCUCCAGAAAAAGGAAAAAAAAAAACAAAAGACAAAAAAAAAAUAAGCGAAACAUCCCUCAAAGCAUCAUCCCCCCCCCCCCUUU; and BC200 RNA mutant U+, GGCCGGGCGCGGUGGCUCACGCCUGUAAUCCCAGCUCUCAGGGAGGCUAAGAGGCGGGAGGAUAGCUUGAGCCCAGGAGUUCGAGACCUGCCUGGGCAAUAUAGCGAGACCCCGUUCUCCUCUUUUUCGUUUUUUUUUUUCUUUUCUGUUUUUUUUUUAAAGCGUAACUUCCCUCAAAGCAACAACCCCCCCCCCCCUUU.

All of the above-described constructs were verified by sequencing. Other constructs used in this work have been described previously (19).

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins.

Plasmids pET(His6-eIF4A) and pET(His6-eIF4B) were used to generate recombinant eIFs 4A and 4B, respectively, as described previously (32). The recombinant proteins were purified as described previously (19). The homogeneity of the purified proteins was verified by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and PCR.

Total RNA from mouse brains was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen). First-strand cDNA was generated by using random hexamers and GoScript reverse transcriptase (Promega). PCR was performed using Phusion hot start II (New England BioLabs).

EMSA analysis.

32P-labeled RNA probes for electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were generated using riboprobe in vitro transcription systems (Promega). Probes (50,000 cpm per reaction mixture, corresponding to an estimated concentration of 1 nM) were heated for 10 min at 70°C, cooled to room temperature, and incubated with protein in binding buffer (300 mM KCl, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 2 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 5% glycerol, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.6) for 20 min at room temperature. EMSAs were also performed at 100 mM or 500 mM KCl, with identical results. For competition assays, unlabeled RNAs were added as competitors as indicated below. RNA-protein complexes were subsequently separated on 5% polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by autoradiography (44). For quantitative analysis, intensities were measured within a quantification box of identical size for each lane; after subtraction of the background, the signal of the complex (bound) was calculated against the total signal (bound plus free). Supershift assays (44) were performed in two ways: (i) with recombinant eIF4B and (ii) with rabbit reticulocyte lysates (RRL). An antibody against eIF4B was obtained from Nahum Sonenberg (37). We also used antibodies against PABP (19), against β3-tubulin (NEB), and against glutathione S-transferase (GST). Antibodies were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Complexes were resolved by 5% PAGE.

Calculation of KD.

EMSAs were performed with titrating amounts of eIF4B ranging from 10 nM to 2 μM. The intensities of bound RNA and free RNA were measured, and the fraction of bound RNA was calculated as a function of eIF4B concentrations. The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) was established by fitting the data to the Hill equation as described previously (36).

Helicase assays.

RNA helicase assays were performed as described previously (19). In brief, a 12-nucleotide (nt) oligonucleotide (GCUUUACGGUGC; Thermo Scientific) was end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (10 pmol, 3,000 Ci/mmol) using polynucleotide kinase (PNK; New England BioLabs). A 44-nt oligonucleotide (GGGAGAAAAACAAAACAAAACAAAACUAGCACCGUAAAGCACGC) was added and annealed to form RNA duplexes in hybridization buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM KCl) by heating at 95°C for 5 min and allowing to cool for at least 30 min at room temperature. Annealed RNA duplexes were diluted in hybridization buffer to a final concentration of 20 fmol/μl for use in helicase assays.

BC and other RNAs were heated at 70°C for 10 min and cooled at room temperature. The reaction mixtures contained BC1 RNA or other RNAs (0.5 μM), eIF4A (1 μM), or eIF4B (0.5 μM), as indicated, and RNasin (40 units; Promega) in helicase buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 70 mM KCl, 2 mM DTT, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM ATP, 5% glycerol) and were incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Labeled duplex RNA (1 μM) was added to the reaction mixtures and incubated at 34°C for 15 min. The reaction products were resolved by native PAGE (15% polyacrylamide).

In vitro translation.

For in vitro translation analysis, the Retic Lysate IVT system (Applied Biosystems) was used as described previously (44). Lysate, reaction buffer, [35S]methionine, and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) mRNA were incubated for 90 min at 30°C in the presence of BC RNAs or derivatives (400 nM) as indicated. Rescue experiments with eIFs were performed with eIF4A (0.5 μM), eIF4B (0.5 μM), and eIF4A and eIF4B in combination (both 0.5 μM). Proteins were added to the reaction mixtures in the presence of BC1 RNA and incubated for 90 min at 30°C. The reaction mixtures were treated with 0.1 mg/ml RNase A (Applied Biosystems) for 10 min at 30°C and were separated by SDS-PAGE. Gels were dried and exposed to X-ray film. Protein bands were visualized and quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). For all experiments, statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software.

(Part of this work was submitted by Valerio Berardi in a partial fulfillment of his Ph.D. thesis at Sapienza Università di Roma.)

RESULTS

Experimental approach.

The overall design of our experimental strategy was based on the hypothesis that structural motif attributes are determinants of RNA function. This consideration is particularly relevant to BC1 and BC200 RNAs as they are nonorthologous, i.e., are phylogenetic descendants of different progenitors in rodent and primate lineages, respectively (20, 21, 38). Therefore, any structural equivalence between the two RNAs can be assumed to be a consequence of common functional necessities (rather than of common phylogenetic ancestry).

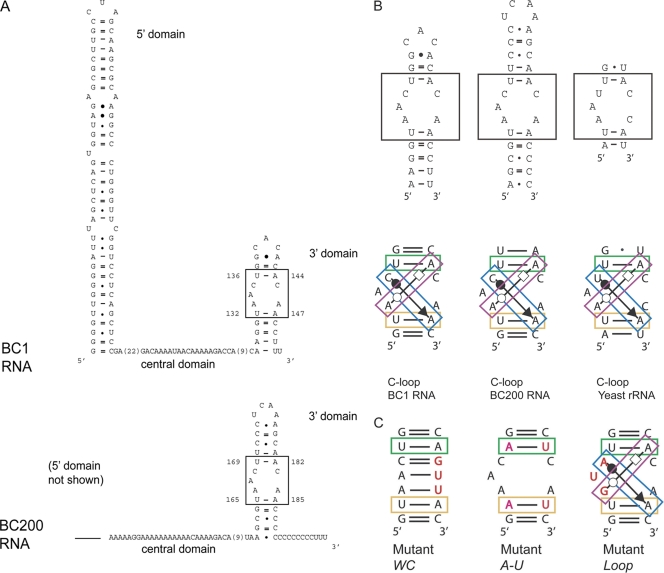

BC1 RNA and BC200 RNA have in common a tripartite structure in which a 5′ stem-loop is connected via a central A-rich region to a 3′ stem-loop (34, 38). While the BC1 5′ domain contains spatial codes that specify synaptodendritic targeting (29), the central and 3′ domains are sites of translational repression competence (14, 43, 44). Conversely, the 3′ domain is incompetent for targeting, while the 5′ domain is incompetent for repression (14, 29, 43, 44). For the functional analysis in this work, we therefore focused on the central and 3′ BC RNA domains (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Rodent BC1 RNA and primate BC200 RNA feature identical C-loop motifs in their 3′ stem-loop domains. (A) C-loop motifs are boxed in secondary structure representations of the two BC RNAs. The structure of BC1 RNA has previously been ascertained by chemical and enzymatic probing (34). (B) BC RNA C-loop motifs are aligned with a previously described eukaryotic C-loop motif (18). C-loop motifs are boxed in the upper panels. Canonical and noncanonical nucleotide interactions are highlighted in the lower panels. Base pairings are typified using the Leontis and Westhof scheme of symbolic representations (15–18). Base pairings are color coded as follows (18): green, cis-WC/WC; blue, cis-WC/SE; purple, trans-WC/H; and yellow, cis-WC/WC. (C) Three types of mutations were introduced into BC RNA C-loop motifs. (i) Mutant WC: conversion to WC base pairings forces the 3′ stem-loops into standard A-form helices, abolishing the C-loop motifs. (ii) Mutant A-U: U-A pairs were changed to A-U pairs. Although this inversion does not alter cis-WC/WC interactions (green and yellow), C-loop motif architecture is intolerant of this change as U cannot substitute for A in motif-essential noncanonical interactions (blue and purple). (iii) Mutant Loop: the long-strand C-loop nucleotides were exchanged in a manner that continues to allow noncanonical interactions (18).

The central domains of BC RNAs are rich in A residues and are therefore unlikely to form higher-order structures (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the 3′ domains of BC RNAs assume a unique stem-loop secondary structure conformation (Fig. 1B) (34). Comparison of the BC1 RNA and BC200 RNA 3′ stem-loop domains revealed a perfect correspondence with eukaryotic C-loop motifs (Fig. 1B) (18). C-loop motifs are recurrent RNA structures in which an asymmetric internal loop is flanked by Watson-Crick (WC) base pairs (Fig. 1B) (16, 18). In eukaryotes, the flanking WC pairs are often of the U-A type, and the internal-loop nucleotides engage with the A residues of the flanking U-A pairs in noncanonical (non-WC) base pairings of the trans-Watson-Crick/Hoogsteen (trans-WC/H) and the cis-Watson-Crick/sugar edge (cis-WC/SE) subtypes (Fig. 1B) (18). These noncanonical interactions are important for motif conformation (16, 18). Results from chemical and enzymatic probing of BC1 RNA (34) also support the notion of a C-loop motif in the 3′ domain, as nucleotides in the long strand of the loop are either unpaired or non-WC paired, while short-strand nucleotides engage in tertiary interactions (18). We therefore surmised that the 3′ domains of BC RNAs represent C-loop motifs and that these motifs are relevant for the translational control functionality of the RNAs.

Thus, the mode of action of BC RNA translational control presents a classical structure-function problem. To solve this problem, we performed a BC RNA structure-function dissection using four experimental paradigms: (i) BC RNA interactions with eIFs 4A and 4B, (ii) BC RNA competition with 18S rRNA for eIF4B interactions, (iii) BC RNA inhibition of eIF4A/4B helicase activity, and (iv) BC RNA translational repression. This analysis revealed, unexpectedly, a dual mode of action in BC RNA translational control.

BC RNAs disrupt interactions of eIF4B with 18S rRNA: role of the 3′ C-loop motif.

eIF4B is a multifunctional protein that has been reported to promote translation initiation by stimulating eIF4A catalytic activity and by recruiting the 40S small ribosomal subunit (in the form of the 43S preinitiation complex) via interactions with 18S rRNA and eIF3 (12, 31). To begin our analysis of eIF4B interactions with BC RNAs, we examined binding by performing electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) with wild-type (WT) and mutant RNAs.

Mutant BC RNAs were used to dissect the respective contributions of central and 3′ domains to RNA functionality. The following mutations were introduced into full-length BC1 and BC200 RNAs (Fig. 1C). (i) The C-loop motif was abolished by conversion into a WC-paired stem-loop (referred to hereinafter as mutant WC). (ii) The flanking U-A pairs of the C-loop motif were inverted to A-U pairs (mutant A-U). The A residues in flanking U-A pairs engage in both canonical and noncanonical interactions (Fig. 1C) (18), and inversion to A-U will therefore maintain the WC pairings but will make the A residues unavailable for cross-loop noncanonical interactions that are essential to the motif. (iii) As a control, the internal loop nucleotides AAC were converted to GUA (mutant Loop), an exchange that is predicted to be neutral for C-loop structure (18). (iv) In addition, BC RNA central domain modifications were introduced by replacing all A residues with U residues (mutant U+).

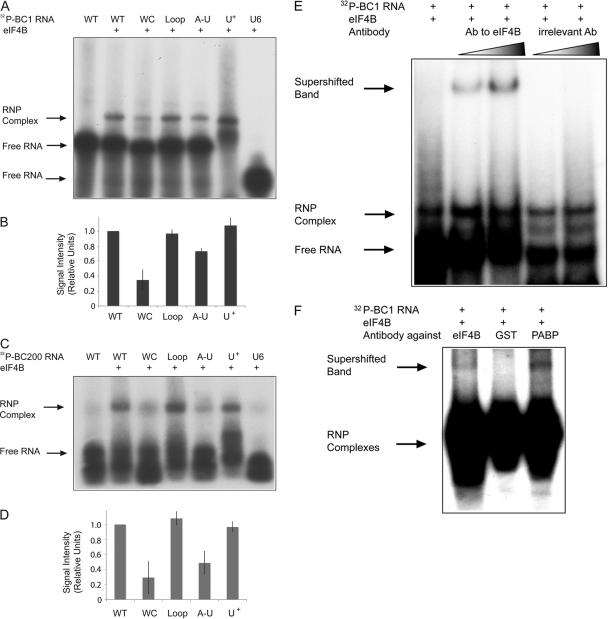

In EMSA experiments, radiolabeled WT BC1 RNA was specifically shifted to lower mobility by eIF4B (Fig. 2A). In contrast, U6 RNA, a small nuclear RNA that was used as a control (19, 43, 44), failed to produce a mobility shift. We next probed the relevance of the 3′ BC1 C-loop motif and the central BC1 A-rich domain for eIF4B interactions. BC1 RNA C-loop mutants WC and A-U both exhibited significantly less binding to eIF4B than did WT BC1 RNA (Fig. 2A and B). In contrast, the interactions of eIF4B with BC1 RNA mutant Loop were indistinguishable from its interactions with WT BC1 RNA. These results indicate that an intact C-loop motif in the 3′ BC1 domain is required for specific binding of the RNA to eIF4B. Analogous results were obtained concerning the interactions of eIF4B with primate BC200 RNA (Fig. 2C and D). In contrast to the 3′ domain C-loop motif, the BC RNA central A-rich domain does not seem to be relevant for interactions with eIF4B. The replacement of all A residues with U residues in this domain (mutant U+) did not result in any discernible difference in eIF4B binding of BC1 RNA (Fig. 2A and B) or of BC200 RNA (Fig. 2C and D).

Fig. 2.

BC1 and BC200 RNA C-loop motifs bind to eIF4B. EMSA experiments were performed with 32P-labeled BC1 RNA, BC200 RNA, and derivatives. Labeled RNAs were incubated with eIF4B (412 nM). (A) WT BC1 RNA produced a band shift with eIF4B (2nd lane) relative to the position of BC1 RNA in the absence of protein (1st lane). The intensities of the RNA-protein complexes were substantially lower with BC1 RNA C-loop mutant WC (3rd lane) than with the WT. C-loop mutant Loop produced an intensity of the shifted band similar to that produced by WT BC1 RNA (4th lane). C-loop mutant A-U produced a significantly lower intensity of the shifted band (5th lane). In contrast, central domain mutant U+ showed no difference from the WT (6th lane). U6 RNA failed to produce a band shift (7th lane; note that free U6 RNA exited the gel). (B) RNA-protein complex band intensities were quantified, and results were plotted as binding to eIF4B relative to the binding of WT BC1 RNA. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean (SEM); n = 4, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), P < 0.001; Tukey post hoc analysis, comparison with WT BC1 RNA, P < 0.001 for WC, P < 0.01 for A-U, P = 0.979 for Loop, and P = 0.744 for U+. (C) WT BC200 RNA produced a shift with eIF4B (2nd lane) relative to the position of BC200 RNA without eIF4B (1st lane). The intensities of the RNA-protein complexes were significantly lower with BC200 RNA C-loop mutants WC and A-U (3rd and 5th lanes, respectively) than with the WT. C-loop mutant Loop produced an intensity of the shifted band similar to that produced by WT BC200 RNA (4th lane). The intensity of the band produced by mutant U+ did not differ significantly differ from that of the WT (6th lane). U6 RNA did not produce a band shift (7th lane). Raw data were as follows (percentage of bound relative to total): WT, 11.5; WC, 2.6; Loop, 11.8; AU, 3.2; and U+, 11.0. (D) Results were plotted as binding to eIF4B relative to that of WT BC200 RNA. Error bars represent SEM; n = 4, one-way ANOVA, P < 0.001; Tukey post hoc analysis, comparison with WT BC200 RNA, P < 0.001 for WC, P < 0.001 for A-U, P = 0.890 for Loop, and P = 0.997 for U+. (E) The addition of an antibody (Ab) against eIF4B to the BC1 RNA-eIF4B complex reaction produced a supershift (2nd lane, 2 μl antibody, and 3rd lane, 3 μl antibody; compare with 1st lane in which no antibody was added). No supershift was observed following the addition of an irrelevant antibody (directed against β3-tubulin; 4th and 5th lanes). (F) In assays using labeled BC1 RNA in RRL, supershifts were observed with antibodies (3 μl each lane) against eIF4B (1st lane) and PABP (3rd lane) but not with an antibody against GST (2nd lane).

For BC1 RNA, we performed EMSA experiments with titrating amounts of eIF4B (see Materials and Methods) to establish binding affinity. These experiments revealed an equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) of 690 nM ± 30 nM (mean ± standard deviation) (data not shown). The KD that was established is in agreement with a previously published dissociation constant for the interaction of eIF4B with RNA (5 × 10−7 M) (26). A midrange affinity may be advantageous, as initiation factors are relatively abundant (7), and a very high affinity may therefore result in locked binding that would be incompatible with dynamic modulation. In a further control, we probed interactions of eIF4B with rat and mouse BC1 RNAs and found that they were indistinguishable (not shown).

To confirm the identity of the RNA-protein complex, we used an antibody specific for eIF4B in supershift experiments. We found that the addition of this antibody to a reaction mixture containing BC1 RNA and recombinant eIF4B resulted in an RNA-protein complex band with further-retarded mobility (Fig. 2E). An irrelevant antibody, directed against β3-tubulin, did not produce a supershift. To probe interactions between BC1 RNA and eIF4B in a cytoplasmic environment, we performed supershift assays with rabbit reticulocyte lysates (RRL). We used antibodies against eIF4B, against PABP, a protein that has previously been shown to bind to BC1 RNA (14, 43, 44), and against GST, an irrelevant protein. Supershifts were observed with anti-eIF4B and anti-PABP but not with anti-GST (Fig. 2F). The results indicate that BC1 RNA is recognized by eIF4B in a cytoplasmic environment.

In summary, we conclude that eIF4B specifically binds BC1 and BC200 RNAs by interacting with a C-loop motif structure in the 3′ stem-loop domains of these RNAs.

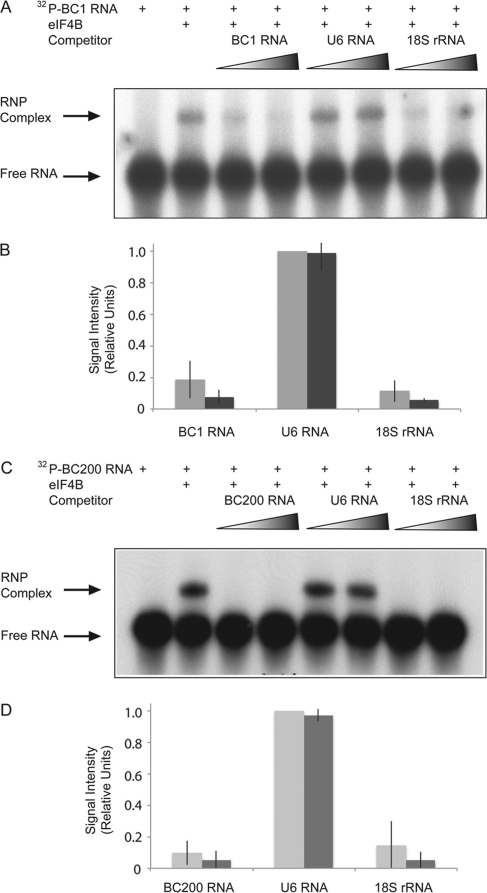

eIF4B binds 18S rRNA, thus effectively forming a bridge between the 5′ end of an mRNA and the 40S small ribosomal subunit (27). Using in vitro RNA selection approaches, Méthot et al. (27) identified RNA stem-loop structures that specifically bound to the eIF4B RNA recognition motif (RRM), and they further showed that these stem-loops competed directly with the binding of 18S rRNA to eIF4B. A remarkable structural similarity is apparent between these in vitro-selected stem-loop RNAs and the 3′ BC RNA C-loop motifs (Fig. 1) (27). We found that the in vitro-selected RNAs of Méthot et al. (27) and BC RNAs compete with each other for binding to eIF4B (data not shown), and we therefore reasoned that BC RNA binding to eIF4B may compete with 18S rRNA binding to the factor. The results shown in Fig. 3 confirmed that this was indeed the case. Increasing concentrations of unlabeled 18S rRNA or of unlabeled BC1 RNA effectively abolished the binding of radiolabeled BC1 RNA to eIF4B (Fig. 3A and B). Analogous results were obtained with BC200 RNA (Fig. 3C and D). In contrast, unlabeled U6 RNA, used at identical concentrations, failed to compete with BC1 RNA for binding to eIF4B (Fig. 3A and B).

Fig. 3.

BC1 RNA and BC200 RNA compete with 18S rRNA for binding to eIF4B. (A) Formation of RNA-protein complexes between BC1 RNA and eIF4B was significantly inhibited by increasing amounts of unlabeled BC1 RNA (3rd and 4th lanes). Unlabeled U6 RNA did not inhibit the formation of BC1 RNA-eIF4B complexes (5th and 6th lanes). In contrast, unlabeled 18S rRNA inhibited the formation of BC1 RNA-eIF4B complexes (7th and 8th lanes). The 1st lane shows labeled BC 1 RNA in the absence of protein, and the 2nd lane shows the formation of BC1 RNA-eIF4B complexes in the absence of competitor RNA. (B) Quantitative analysis confirmed competition of BC1 RNA with 18S rRNA for eIF4B binding. Competitor RNA concentrations were 1.7 nM (light gray) or 3.4 nM (dark gray). Error bars show SEM; n = 4, one-way ANOVA, P < 0.001; Tukey post hoc analysis, comparison with U6 RNA, P < 0.001 for BC1 RNA and 18S rRNA. (C) Formation of BC200 RNA-eIF4B complexes was reduced by unlabeled competitor BC200 RNA (3rd and 4th lanes) and by unlabeled 18S rRNA (7th and 8th lanes). Unlabeled U6 RNA did not inhibit complex formation (5th and 6th lanes). The 1st lane shows labeled BC200 RNA, and the 2nd lane shows the formation of BC200 RNA-eIF4B complexes in the absence of competitor RNA. (D) Quantitative analysis confirmed competition of BC200 RNA with 18S rRNA for eIF4B binding. Competitor RNA concentrations were 1.7 nM (light gray) or 3.4 nM (dark gray). Error bars show SEM; n = 4, one-way ANOVA, P < 0.001; Tukey post hoc analysis, comparison with U6 RNA, P < 0.001 for BC200 RNA and 18S rRNA.

The combined results thus indicate that C-loop motifs in the 3′ BC RNA stem-loop structures specifically interact with eIF4B and that BC RNAs effectively compete with 18S rRNA for binding to the factor.

BC RNAs target eIF4A helicase activity: role of the central A-rich domain.

In addition to its role in 40S ribosomal subunit recruitment, eIF4B is also known to stimulate the helicase activity of eIF4A (7, 31). Because BC RNAs inhibit the helicase activity of eIF4A (19), the possibility is raised that eIF4B may affect the ability of BC RNAs to target the catalytic activity of eIF4A. To address this question, we performed two sets of experiments.

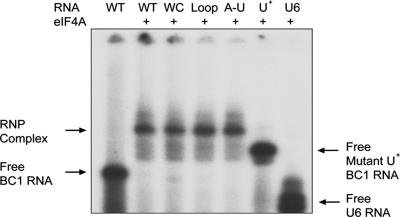

In the first approach, we examined BC RNA motif interactions with eIF4A by EMSA analysis. As shown in Fig. 4, WT BC1 RNA but not U6 RNA is specifically shifted to lower mobility by eIF4A. Remarkably, all of the BC1 RNA C-loop motif mutants described above bound to eIF4A in a manner indistinguishable from WT BC1 RNA (Fig. 4). Analogous results were obtained with BC200 RNA (not shown). The data indicate that the 3′ BC RNA C-loop motifs do not mediate binding to eIF4A. In clear contrast, however, conversion of the central A-rich domain to a central U-rich domain (mutant U+) completely abolished the binding of BC RNAs to eIF4A (Fig. 4; also data not shown). Thus, the BC RNA central domains are important for binding to eIF4A, while in contrast, the 3′ C-loop motifs are irrelevant in this regard.

Fig. 4.

The central A-rich domain of BC1 RNA mediates binding to eIF4A. Labeled RNAs were incubated with eIF4A (820 nM). WT BC1 RNA produced a band shift with eIF4A (2nd lane) relative to the position of BC1 RNA in the absence of protein (1st lane). RNA-protein complexes were also observed with BC1 RNA C-loop mutants WC (3rd lane), Loop (4th lane), and A-U (5th lane). In contrast, central domain mutant U+ failed to produce a band shift (6th lane). Similarly, U6 RNA failed to interact with eIF4A (7th lane).

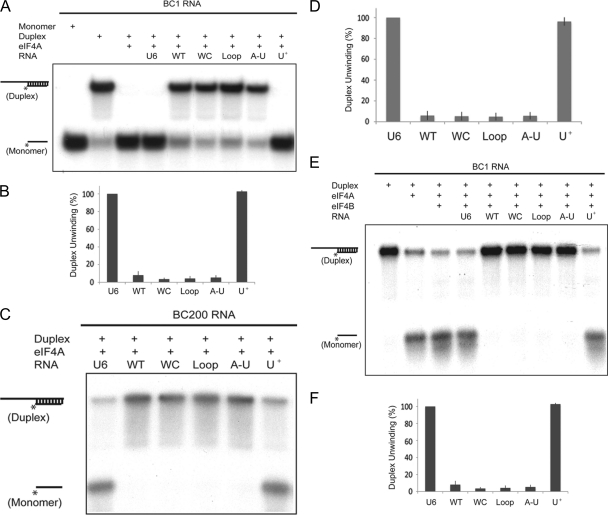

In the second approach, we focused on the helicase activity of eIF4A and its inhibition by BC RNAs. Figure 5A shows that eIF4A effectively converted a double-stranded RNA duplex into its constituent monomers. This helicase activity was significantly repressed in the presence of BC1 RNA but not in the presence of U6 RNA, as reported previously (19). All three C-loop motif mutants were indistinguishable from WT BC1 RNA in their ability to repress eIF4A helicase activity (Fig. 5A). Conversely, the central domain mutation that abolished binding of BC1 RNA to eIF4A also abolished the capacity of BC1 RNA to inhibit the helicase activity of the factor. Evidently, eIF4A's helicase-repressive functionality is mediated by the central A-rich domain of BC1 RNA, while the 3′ C-loop motif, in contrast, does not contribute (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

The BC RNA A-rich central domains mediate repression of eIF4A helicase activity. RNA duplexes (12/44 nt, 32P-labeled on the 12-nt short strand) were used as helicase substrates in the presence of 1 mM ATP. (A and B) The BC1 RNA central domain mediates repression of eIF4A helicase activity. Labeled RNA monomer and RNA duplexes in the absence of eIF4A were run in the 1st and 2nd lanes, and eIF4A-unwound duplexes were run in the 3rd lane. U6 RNA did not significantly inhibit unwinding (4th lane). WT BC1 RNA inhibited RNA duplex unwinding (5th lane). BC1 RNA C-loop mutants WC, Loop, and A-U (6th to 8th lanes) all inhibited unwinding in a manner indistinguishable from the results for WT BC1 RNA. In contrast, central domain mutant U+ did not inhibit unwinding (9th lane). (B) Quantitative analysis confirmed the above-described results. Error bars show SEM; n = 4, one-way ANOVA, P < 0.001; Tukey post hoc analysis, comparison with U6 RNA, P < 0.001 for WT BC1 RNA and mutants WC, Loop, and A-U and P = 0.970 for mutant U+; comparison with WT BC1 RNA, P < 0.001 for U6 RNA and mutant U+, P = 0.803 for WC, P = 0.891 for Loop, and P = 0.969 for A-U. (C and D) The BC200 RNA central domain mediates repression of eIF4A helicase activity. WT BC200 RNA significantly repressed eIF4A helicase activity (2nd lane) while U6 RNA did not (1st lane). BC200 RNA C-loop mutants WC, Loop, and A-U (3rd to 5th lanes) inhibited eIF4A helicase activity in a manner indistinguishable from the results for WT BC200 RNA. In contrast, central domain mutant U+ (6th lane) did not significantly inhibit duplex unwinding (indistinguishable from the results for U6 RNA in the 1st lane). (D) The above-described results were confirmed by quantitative analysis. Error bars show SEM; n = 4, one-way ANOVA, P < 0.001; Tukey post hoc analysis, comparison with U6 RNA, P < 0.001 for WT BC200 RNA and mutants WC, Loop, and A-U and P = 0.976 for mutant U+; comparison with WT BC200 RNA, P < 0.001 for U6 RNA and mutant U+ and P = 1.0 for mutants WC, Loop, and A-U. (E and F) eIF4B-stimulated eIF4A helicase activity is repressed by BC1 RNA via its central A-rich domain. Labeled RNA duplexes in the absence of protein were run in the 1st lane. eIF4A (2nd lane) or eIF4A and eIF4B in combination (3rd lane) were added. WT BC1 RNA and BC1 RNA C-loop mutants WC, Loop, and A-U inhibited RNA duplex unwinding (5th to 8th lanes) in a manner indistinguishable from each other. In contrast, neither BC1 RNA central domain mutant U+ (9th lane) nor U6 RNA (4th lane) inhibited unwinding. (F) Quantitative analysis confirmed the above-described results. Error bars show SEM; n = 4, one-way ANOVA, P < 0.001; Tukey post hoc analysis, comparison with U6 RNA, P < 0.001 for WT BC1 RNA and C-loop mutants WC, Loop, and A-U and P = 0.998 for mutant U+; comparison with WT BC1 RNA, P < 0.001 for U6 RNA and mutant U+ and P = 1.0 for mutants WC, Loop, and A-U.

The above-described experiments were repeated with BC200 RNA, and analogous results were obtained (Fig. 5C). As with BC1 RNA, conversion of the central region from A-rich to U-rich abolished the functional ability of BC200 RNA to repress eIF4A helicase activity. In contrast, BC200 RNA C-loop mutants were indistinguishable from WT BC200 RNA in this respect (Fig. 5C and D). These data provide further corroboration of the notion that BC1 and BC200 RNAs, although not orthologs, are functional analogs.

In a further set of experiments, we investigated whether the interaction of BC1 RNA with eIF4A-stimulating eIF4B would have any impact on BC1 repression of eIF4A helicase activity. In agreement with earlier data (12, 19, 31), we observed a helicase-stimulatory effect of eIF4B (Fig. 5E). Such eIF4B-stimulated eIF4A helicase activity was significantly repressed by BC1 RNA, in a manner similar to eIF4A helicase repression in the absence of eIF4B (Fig. 5E and F). The eIF4A/4B helicase-repressive capacity of BC1 RNA was not observed with a BC1 RNA central domain mutant that does not bind eIF4A. Notably, however, all BC1 RNA C-loop motif mutants were fully effective in repressing eIF4B-stimulated eIF4A helicase activity and were indistinguishable in this activity from WT BC1 RNA (Fig. 5E and F). Because the 3′ domain C-loop motif is required for interactions with eIF4B, the combined results indicate that direct interactions with eIF4A, mediated through the central A-rich domain, underlie the eIF4A helicase inhibitory competence of BC1 RNA. In contrast, interactions of the 3′ domain C-loop motif with eIF4B do not affect the eIF4A helicase inhibitory functionality of BC1 RNA, i.e., they are entirely dispensable in this regard. Thus, taken together, the data suggest that interactions of the RNA with eIF4A and eIF4B are physically and functionally segregated.

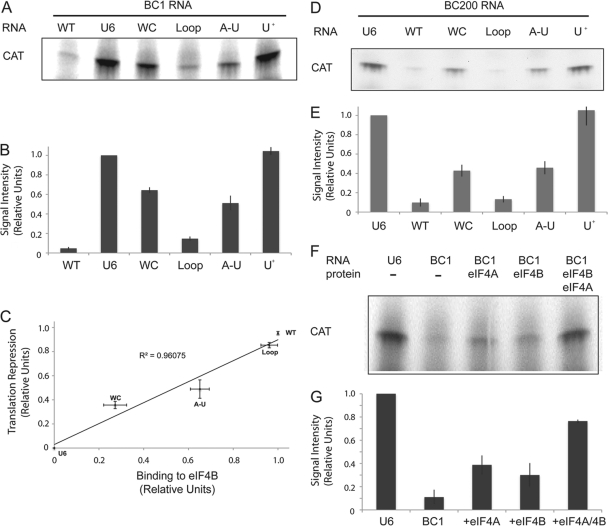

A dual mode of action underlies translational repression by BC RNAs.

The above-described data show that BC RNAs engage in distinctly segregated interactions with eIF4A and eIF4B. What are the functional consequences of these interactions in BC RNA-mediated translational control? We addressed this question using in vitro translation assays with rabbit reticulocyte lysates (RRL) (43, 44). As a control for BC RNAs, we used U6 RNA, an snRNA that we have shown not to affect translation in the RRL or other systems (19, 43, 44; also data not shown). CAT mRNA was used as a reporter for BC RNA-mediated regulation of translational activity. CAT mRNA was chosen because its 5′ UTR is predicted to assume a structured conformation that requires unwinding for efficient translation (19). As a further control, we used pateamine, a specific inhibitor of eIF4A helicase activity (3), to verify that translation of CAT mRNA in the RRL system is in fact eIF4A dependent (not shown).

We first verified that BC1 RNA, used in the nanomolar concentration range, effectively inhibited translation of CAT mRNA in the RRL system (Fig. 6A and B). U6 RNA, in contrast, had no effect (Fig. 6A and B). We next probed translational repression by BC1 RNA C-loop mutants. C-loop mutations that inhibited binding of BC1 RNA to eIF4B (Fig. 2) also displayed reduced translational repression competence (Fig. 6A and B). Subsequently, to examine the extent to which the ability to bind to eIF4B correlated with repression competence, we subjected quantitative data obtained for eIF4B binding (Fig. 2B) and for translational repression (Fig. 6B) to linear regression analysis (Fig. 6C). Such analysis revealed that for the WT and mutant RNAs tested, eIF4B binding and translational repression are tightly correlated (R2 = 0.96075). Thus, an inability to bind to eIF4B is reflected in a quantitatively corresponding inability to repress translation (Fig. 6C). In conclusion, the data suggest that BC1 RNA's translational repression competence relies on interactions with eIF4B.

Fig. 6.

Translational repression by BC RNAs is dualistic and mediated both by their 3′ domain C-loop motifs, interacting with eIF4B, and by their central A-rich domains, interacting with eIF4A. (A) WT BC1 RNA inhibited translation of CAT mRNA in RRL, whereas U6 RNA did not. The translation repression competence of BC1 RNA C-loop mutants was diminished to various degrees (compared to that of WT BC1 RNA), whereas BC1 RNA central domain mutant U+ (lane 6) was completely ineffective in repressing translation, in a manner that was indistinguishable from the results for U6 RNA. (B) For quantitative analysis, the intensities of the protein product bands were normalized against the one obtained in the presence of U6 RNA, as described previously (19). Error bars show SEM; n = 4, one-way ANOVA, P < 0.001; Tukey post hoc analysis, comparison with U6 RNA, P < 0.001 for WT BC1 RNA and mutants WC, Loop, and A-U and P = 0.965 for mutant U+; comparison with WT BC1 RNA, P < 0.001 for U6 RNA and mutants WC, A-U, and U+ and P = 0.485 for mutant Loop. (C) Regression analysis showed that binding to eIF4B and translational repression by BC1 RNA are tightly correlated, indicating that complete binding inability results in complete inability to mediate repression. Relative quantitative repression competence (from the experiments whose results are shown in panels A and B) was plotted against relative quantitative binding to eIF4B (from the experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 2) for the RNAs indicated. A correlation coefficient of R2 = 0.96075 was obtained. Error bars show SEM. (D) Analogous to BC1 RNA, BC200 RNA inhibited translation of CAT mRNA in RRL. The repression competence of BC200 RNA C-loop and central domain mutants was diminished to degrees similar to the results for the respective BC1 RNA mutants. (E) BC200 RNA quantitative analysis results are as follows. Error bars show SEM; n = 4, one-way ANOVA, P < 0.001; Tukey post hoc analysis, comparison with U6 RNA, P < 0.001 for WT BC200 RNA and mutants WC, Loop, and A-U and P = 0.996 for mutant U+; comparison with WT BC200 RNA, P < 0.001 for U6 RNA and mutant U+, P < 0.01 for mutants WC and A-U, and P = 1.0 for mutant Loop. (F) Recombinant eIFs 4A and 4B restored in vitro translation in RRL. No protein was added in the 1st and 2nd lanes. Recombinant eIF4A was added in the 3rd lane, recombinant eIF4B protein in the 4th lane, and both recombinant factors in the 5th lane. (G) Quantitative analysis results are as follows. Error bars show SEM; n = 4, one-way ANOVA, P < 0.001; Tukey post hoc analysis, comparison with U6 RNA, P < 0.001 for WT BC1 RNA, addition of eIF4A, addition of eIF4B, and addition of eIFs 4A and 4B in combination.

In addition, we examined translational repression by BC1 RNA central domain mutant U+ (conversion from A rich to U rich). As mentioned above, for the central domain, we were able to generate a single mutant that completely abrogated the binding of BC1 RNA to eIF4A (Fig. 4) without affecting binding to eIF4B (Fig. 2). BC1 RNA mutant U+ also quantitatively blocked the helicase activity of eIF4A (Fig. 5A and B). We now show that this central domain mutant was also completely ineffective as a translational repressor (Fig. 6A and B). Thus, the ability of the central A-rich domain to bind to eIF4A and inhibit its helicase activity is expressed in the ability of BC1 RNA to repress translation. In summary, we conclude that interactions of BC1 RNA with eIF4B and with eIF4A are equally requisite for translational repression competence.

In a further set of experiments, we probed translational repression by primate BC200 RNA in RRL. The results obtained (Fig. 6D and E) were analogous to those described above that were obtained with BC1 RNA (Fig. 6A and B). As with BC1 RNA, the translational repression competence of BC200 RNA was significantly reduced in C-loop mutants WC and A-U but not in C-loop mutant Loop in comparison to that of the WT (Fig. 6D and E). BC200 RNA central domain mutant U+ was repression incompetent in a manner indistinguishable from U6 RNA. Thus, in conclusion, both BC RNAs use the same dual mode of action to target eIF4B and eIF4A for translational repression, again supporting the notion of functional analogy of these nonorthologous regulatory RNAs.

For an independent assessment of the roles of eIFs 4A and 4B as targets of BC1-mediated translational repression, we performed rescue experiments in which recombinant eIF4A, recombinant eIF4B, or both factors in combination were added to the RRL translation system (Fig. 6F and G). While the translation of CAT mRNA was reduced by BC1 RNA to 11% of the translational efficiency of unrepressed RRL, the combined presence of both eIFs restored translation efficiency in the presence of BC1 RNA to 76% of control levels. The translational efficiency was restored to 39% by eIF4A alone and to 30% by eIF4B alone. Thus, the restoration appears to be additive, indicating that translational repression by BC1 RNA occurs via independent interactions with these two factors.

In summary, the data indicate that BC RNAs use distinctly segregated dual-motif interactions to repress translation. In the first mechanism, 3′ C-loop motif interactions with eIF4B result in a reduced ability of the factor to bind 18S rRNA. In the second mechanism, central A-rich domain interactions with eIF4A result in reduced catalytic activity of the helicase. Both mechanisms operate individually as mediators of BC RNA translational control competence.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we introduce a novel mode of action in RNA translational control. Previous work has shown that neuronal regulatory BC RNAs repress translation by targeting components of the eIF4 family of initiation factors (19, 43, 44). We now report that within this family, eIF4B is a direct target of the translational repression mediated by BC RNAs. Interacting with eIF4B through their 3′ C-loop motifs, BC RNAs interfere with the ability of this factor to bind 18S rRNA. In addition, BC RNAs interact with eIF4A and inhibit its helicase activity. Thus, by interacting with two members of the eIF4 family, BC RNAs employ a dual mode of action by targeting two distinct but complementary mechanisms that are required for translation initiation.

BC RNA interactions with eIF4B: the 3′ C-loop motif domain and 18S rRNA competition.

eIF4B is a multifunctional translation factor. It has been reported to promote translation initiation by using three independent mechanisms (6, 12, 27, 31, 35), i.e., (i) by stimulation of the helicase activity of eIF4A, (ii) by binding to eIF3 (which in turn interacts with eIF4G and the small ribosomal subunit, thus linking it with the mRNA), and (iii) by interacting with the small ribosomal subunit by binding to 18S rRNA. eIF4B features two RNA binding domains, an RNA recognition motif (RRM) located near the N terminus and two arginine-rich motifs (ARMs) located in the C-terminal half (4, 26, 27). While the ARMs bind RNA (i.e., mRNA) unspecifically but with high affinity, the RRM specifically binds 18S rRNA (27). Thus, by interacting simultaneously with an mRNA and with the 40S small ribosomal subunit via 18S rRNA, eIF4B provides a bridging mechanism for the recruitment of the 40S small ribosomal subunit to the mRNA during 48S initiation complex formation.

We now show that eIF4B specifically interacts with C-loop motifs in the 3′ stem-loop domains of BC1 and BC200 RNAs. The C-loop motifs are identical in these nonorthologous RNAs. C-loops are RNA motifs in which an asymmetric internal loop is flanked by standard WC base pairs and stabilized by cross-strand noncanonical interactions of the trans-WC/H and cis-WC/SE types (16, 18). Our analysis revealed that interactions between BC RNAs and eIF4B are intolerant of nucleotide alterations that are motif disruptive (e.g., conversion of noncanonical nucleotide interactions into standard WC interactions or inversion of motif-essential U-A pair orientation). Thus, nucleotide immutability in these positions is a reflection of their essential roles in motif architecture.

eIF4B has previously been shown to interact with 18S rRNA through its RRM (27). Using in vitro RNA selection, these authors identified a number of stem-loop structures that specifically bound to the eIF4B RRM. Subsequent structural work further corroborated these data (4). The selected stem-loops featured asymmetric internal loops with flanking WC pairs, often of the U-A type (e.g., A2, A13, and B6) (27). We assumed that these stem-loop structures were selected because they mimic C-loop motifs, and we found that they do compete with BC RNAs for binding to eIF4B. In turn, BC RNAs and in vitro-selected stem-loops all compete with 18S rRNA for binding to eIF4B (Fig. 3) (27). The combined data lead us to the conclusion that BC RNA C-loop motifs are specifically recognized by the eIF4B RRM and that this interaction is in direct competition with 18S rRNA binding to the same RRM. Thus, taken together, the data support the notion that BC RNAs repress translation initiation by preventing interactions of eIF4B with 18S rRNA and, thus, with the small ribosomal subunit. This notion is also consistent with earlier data showing that BC RNAs repress 48S initiation complex formation, i.e., small ribosomal subunit recruitment to the mRNA (43, 44).

BC RNA interactions with eIF4A: the central A-rich domain and helicase repression.

eIF4A is an ATP-dependent RNA helicase (6, 12, 31). mRNAs with significant double-stranded-structure content in their 5′ UTRs require the helicase activity of eIF4A for efficient initiation (31, 39). Previous work has shown that BC1 and BC200 RNAs inhibit the helicase activity of eIF4A (19). Here, we performed differential mutagenesis analysis to dissect the respective functional contributions and potential mutual interactions of the eIF4A and eIF4B branches of BC RNA translational repression competence.

We verified that both BC1 RNA and BC200 RNA effectively repressed eIF4A helicase activity. Such repression was not overcome by the helicase-stimulatory activity of eIF4B. BC RNA repression of eIF4A helicase activity was effectively abolished by conversion of the BC RNA A-rich central domain into a U-rich central domain. Conversely, none of the alterations in the 3′ domain that disrupt the C-loop motif structure had any effect on the helicase repression capacity of BC RNAs. These data have two relevant functional implications.

(i) Indispensable for eIF4A helicase repression are the A residues in the central, single-stranded BC RNA domain. The nature of some non-A residues interspersed in this domain appears to be irrelevant for helicase repression competence: for instance, a GAC motif that is common to both BC1 RNA and BC200 RNA can be altered without affecting eIF4A helicase repression (not shown). Helicase repression is thus mediated by a single-stranded A-rich domain that is bordered at the 3′ end by a stem-loop structure. It is, however, immaterial for the helicase repression competence of BC RNAs whether the 3′ stem-loop is of a canonical A-form helical type or of a noncanonical C-loop motif type. Thus, with respect to their helicase-inhibiting activity, BC RNAs seem to take advantage of a key functional property within the group of DEAD-box RNA helicases (of which eIF4A is a prototypical member): the requirement that the helicase first bind to a single-stranded region before it can be loaded onto a double-stranded region to initiate strand separation (10).

(ii) eIF4B, on the other hand, does not seem to play any significant role in BC RNA helicase repression. The degree to which the helicase activity of eIF4A is repressed by BC RNAs is not dependent on whether eIF4B is present to stimulate eIF4A. Furthermore, BC RNA C-loop motif mutants, unable to bind to eIF4B, nevertheless repress eIF4A helicase activity in a manner indistinguishable from that of WT BC RNAs. We therefore conclude that the interactions of BC RNAs with eIF4A and eIF4B result in dualistic functional consequences that are mechanistically distinct and independent from each other.

BC RNAs: dualistic mode of action in translational control.

BC RNA translational control uses a two-pronged approach to target two initiation mechanisms that are mediated by eIFs 4A and 4B, respectively. Consequently, translation in RRL, repressed by BC1 RNA, is partially restored by either recombinant eIF4A or recombinant eIF4B and almost completely restored (to nearly 80%) by both factors in combination. These data suggest that the translational repression by BC RNAs occurs via two modular branches. A third branch is possible, as BC1 RNA has previously been shown to interact with PABP (14, 43, 44). The PABP branch, however, appears to contribute at most 20% to the repression competence of BC1 RNA (19), a degree that is in agreement with the above-mentioned observation that eIFs 4A and 4B in combination are able to restore translation to within about 20% of control levels.

The two main mechanisms that are targeted by BC RNAs enable recruitment of the 40S ribosomal subunit to the mRNA by (i) bridging of the mRNA to 18S rRNA by eIF4B and (ii) unwinding of the 5′ UTR mRNA duplex content by eIF4A. Although these two mechanisms are functionally independent of each other, their dual repression by BC RNAs appears to be interlocked. Incapacitation of one branch of the dual BC RNA translational repression competence is dominant, i.e., is not rescued by the respective other branch. The underlying molecular basis for this coupling is unknown and remains to be explored in future work. It is known, however, that eIFs 4A and 4B bind synergistically to BC1 RNA (19). Also, eIFs 4A and 4B interact with other initiation factors, e.g., eIF4A with eIF4G, which at the same time interacts with PABP, which in turn interacts with eIF4B (1, 6, 12, 31). In a cytoplasmic environment (e.g., in RRL), such additional protein-protein interactions may be responsible for the observed repression coupling. We speculate that a nascent “initiation” complex may assemble on BC RNAs. However, such a complex, which may include a to-be-initiated mRNA, will be nonproductive as it will be prevented from recruiting the 40S small ribosomal subunit. We also note that eIF4B is a downstream effector target of two signaling pathways (37). Future work will address the question of whether signaling-induced phosphorylation of eIF4B is a modulating factor in BC RNA translational repression.

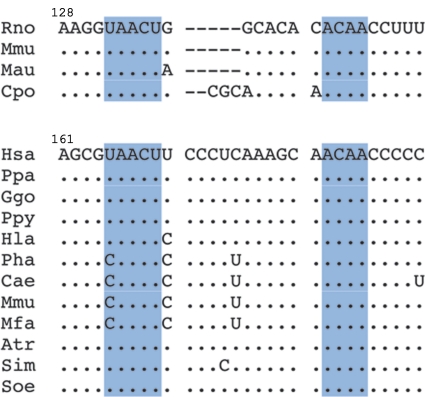

In all experimental approaches used in this work, the nonorthologous BC1 and BC200 RNAs proved functionally analogous. This functional equivalence is determined by common architectural RNA motifs, not by shared nucleotide sequences. Thus, BC RNA C-loop motifs are maintained in evolution: the C-loop motifs are invariant between BC1 RNA and BC200 RNA (despite the nonorthologous origin of these two RNAs), as well as among different BC1 RNA species in rodents and among different BC200 RNA species in primates (Fig. 7). However, notwithstanding the fact that our data are consistent with C-loop motifs as functional elements in BC RNAs, additional structural studies are desirable for further corroboration.

Fig. 7.

Conservation of BC1 C-loop motifs in rodents and BC200 C-loop motifs in primates (Anthropoidea). The 3′ domains of BC1 RNA (top) and BC200 RNA (bottom) are given for all published sequences. C-loop motif nucleotides, shaded in light blue, are invariant across all species shown with the exception of a U-to-C transition in four primate species. This transition results in the replacement of standard WC U-A pairs with wobble WC C · A pairs. This pair (U165-A185 in human BC200 RNA) is the basal C-loop WC pair. While U-A pairs are most frequently observed in this position in eukaryotic C-loops, C · A pairs are not uncommon (16). A second U-A to C · A transition occurs at position 170 to 181, i.e., outside the C-loop motif. (Sequence data are from references 21 and 38.) Species: Rattus norvegicus (Rno), Mus musculus (Mmu), Mesocrietus auratus (Mau), Cavia porcellus (Cpo), Homo sapiens (Hsa), Pan paniscus (Ppa), Gorilla gorilla (Ggo), Pongo pygmaeus (Ppy), Hylobates lar (Hla), Papio hamadryas (Pha), Chlorocebus aethiops (Cae), Macaca mulatta (Mmu), Macaca fascicularis (Mfa), Aotus trivirgatus (Atr), Saguinus imperator (Sim), and Saguinus oedipus (Soe). Nucleotide numbering is given for Rno (BC1 RNA) and Hsa (BC200 RNA).

Our data support the notion that, in contrast to regulatory RNAs that base pair with target nucleic acids (and therefore require sequence conservation), regulatory RNAs such as BC1 and BC200 RNAs that interact with proteins will typically exhibit analogous higher-order motif structures (30). BC1 RNA and BC200 RNA have evolved independently during mammalian phylogenetic development, the former in the rodent lineage and the latter in the primate lineage (20, 21). We posit that BC1 and BC200 RNAs were selected in vivo, during the course of mammalian evolution, for their ability to interact specifically with eIFs 4A and 4B and, thus, to control neuronal translation at the level of initiation.

We further posit that RNA selection and recruitment became necessary as a result of the ever-increasing complexities of mammalian brains. Increasing brain complexity necessitated higher numbers of molecular regulators that could contribute to the long-term control of neuronal function and plasticity. Because the limited repertoire of protein regulators was probably exhausted in early eukaryotic evolution (23–25), the new brain regulators were recruited from the much larger pool of non-protein-coding RNAs. Thus, while mammalian neuronal function remains protein executed, it has to a significant degree become RNA regulated. We propose that RNA control of gene expression has become a phylogenetic driving force in the development of neural systems and organismal complexity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Anna Iacoangeli, Daisy Lin, Christopher Hellen, and Tatyana Pestova for advice and discussion and Jeremy Weedon (SUNY Brooklyn Scientific Computing Center) for statistical consultation. We also thank Jerry Pelletier, who provided pateamine, and Nahum Sonnenberg, who provided the antibody against eIF4B. The thesis work of V.B. was conducted under the joint tutorship of G.R. and H.T. according to an interinstitutional agreement between Sapienza Università di Roma and SUNY Brooklyn.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants NS046769 and DA026110 (H.T.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 September 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bushell M., et al. 2001. Disruption of the interaction of mammalian protein synthesis eukaryotic initiation factor 4B with the poly(A)-binding protein by caspase- and viral protease-mediated cleavages. J. Biol. Chem. 276:23922–23928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cao X., Yeo G., Muotri A. R., Kuwabara T., Gage F. H. 2006. Noncoding RNAs in the mammalian central nervous system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 29:77–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cristofanilli M., Thanos S., Brosius J., Kindler S., Tiedge H. 2004. Neuronal MAP2 mRNA: species-dependent differential dendritic targeting competence. J. Mol. Biol. 341:927–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fleming K., et al. 2003. Solution structure and RNA interactions of the RNA recognition motif from eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4B. Biochemistry 42:8966–8975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gebauer F., Hentze M. W. 2004. Molecular mechanisms of translational control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5:827–835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gingras A.-C., Raught B., Sonenberg N. 1999. eIF4 initiation factors: effectors of mRNA recruitment to ribosomes and regulators of translation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68:913–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hershey J. W. B., Merrick W. C. 2000. The pathway and mechanism of initiation of protein synthesis, p. 33–88. In Sonenberg N., Hershey J. W. B., Mathews M. B. (ed.), Translational control of gene expression. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iacoangeli A., Bianchi R., Tiedge H. 2010. Regulatory RNAs in brain function and disorders. Brain Res. 1338:36–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jackson R. J., Hellen C. U., Pestova T. V. 2010. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11:113–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jankowsky E., Fairman M. E. 2007. RNA helicases—one fold for many functions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 17:316–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Job C., Eberwine J. 2001. Localization and translation of mRNA in dendrites and axons. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2:889–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kapp L. D., Lorsch J. R. 2004. The molecular mechanics of eukaryotic translation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73:657–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kindler S., Wang H., Richter D., Tiedge H. 2005. RNA transport and local control of translation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21:223–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kondrashov A. V., et al. 2005. Inhibitory effect of naked neural BC1 RNA or BC200 RNA on eukaryotic in vitro translation systems is reversed by poly(A)-binding protein (PABP). J. Mol. Biol. 353:88–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leontis N. B., Stombaugh J., Westhof E. 2002. The non-Watson-Crick base pairs and their associated isostericity matrices. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:3497–3531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leontis N. B., Westhof E. 2003. Analysis of RNA motifs. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13:300–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leontis N. B., Westhof E. 2001. Geometric nomenclature and classification of RNA base pairs. RNA 7:499–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lescoute A., Leontis N. B., Massire C., Westhof E. 2005. Recurrent structural RNA motifs, isostericity matrices and sequence alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:2395–2409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lin D., Pestova T. V., Hellen C. U., Tiedge H. 2008. Translational control by a small RNA: dendritic BC1 RNA targets the eukaryotic initiation factor 4A helicase mechanism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28:3008–3019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martignetti J. A., Brosius J. 1993. BC200 RNA: a neural RNA polymerase III product encoded by a monomeric Alu element. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:11563–11567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martignetti J. A., Brosius J. 1993. Neural BC1 RNA as an evolutionary marker: guinea pig remains a rodent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:9698–9702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mathews M. B., Sonenberg N., Hershey J. W. B. (ed.). 2007. Translational control in biology and medicine. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mattick J. S. 2009. The genetic signatures of noncoding RNAs. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mattick J. S. 2004. RNA regulation: a new genetics? Nat. Rev. Genet. 5:316–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mattick J. S., Makunin I. V. 2006. Non-coding RNA. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15(spec. no. 1):R17–R29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Méthot N., Pause A., Hershey J. W., Sonenberg N. 1994. The translation initiation factor eIF-4B contains an RNA-binding region that is distinct and independent from its ribonucleoprotein consensus sequence. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:2307–2316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Méthot N., Pickett G., Keene J. D., Sonenberg N. 1996. In vitro RNA selection identifies RNA ligands that specifically bind to eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4B: the role of the RNA recognition motif. RNA 2:38–50 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miyashiro K. Y., Bell T. J., Sul J. Y., Eberwine J. 2009. Subcellular neuropharmacology: the importance of intracellular targeting. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 30:203–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Muslimov I. A., Iacoangeli A., Brosius J., Tiedge H. 2006. Spatial codes in dendritic BC1 RNA. J. Cell Biol. 175:427–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pang K. C., Frith M. C., Mattick J. S. 2006. Rapid evolution of noncoding RNAs: lack of conservation does not mean lack of function. Trends Genet. 22:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pestova T., Lorsch J. R., Hellen C. U. T. 2007. The mechanism of translation initiation in eukaryotes, p. 87–128. In Mathews M. B., Sonenberg N., Hershey J. W. B. (ed.), Translational Control in Biology and Medicine. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pestova T. V., Hellen C. U., Shatsky I. N. 1996. Canonical eukaryotic initiation factors determine initiation of translation by internal ribosomal entry. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:6859–6869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pfeiffer B. E., Huber K. M. 2006. Current advances in local protein synthesis and synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 26:7147–7150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rozhdestvensky T. S., Kopylov A. M., Brosius J., Huttenhofer A. 2001. Neuronal BC1 RNA structure: evolutionary conversion of a tRNAAla domain into an extended stem-loop structure. RNA 7:722–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rozovsky N., Butterworth A. C., Moore M. J. 2008. Interactions between eIF4AI and its accessory factors eIF4B and eIF4H. RNA 14:2136–2148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ryder S. P., Recht M. I., Williamson J. R. 2008. Quantitative analysis of protein-RNA interactions by gel mobility shift. Methods Mol. Biol. 488:99–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shahbazian D., et al. 2006. The mTOR/PI3K and MAPK pathways converge on eIF4B to control its phosphorylation and activity. EMBO J. 25:2781–2791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Skryabin B. V., et al. 1998. The BC200 RNA gene and its neural expression are conserved in Anthropoidea (Primates). J. Mol. Evol. 47:677–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Svitkin Y. V., et al. 2001. The requirement for eukaryotic initiation factor 4A (elF4A) in translation is in direct proportion to the degree of mRNA 5′ secondary structure. RNA 7:382–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tiedge H., Chen W., Brosius J. 1993. Primary structure, neural-specific expression, and dendritic location of human BC200 RNA. J. Neurosci. 13:2382–2390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tiedge H., Fremeau R. T., Jr., Weinstock P. H., Arancio O., Brosius J. 1991. Dendritic location of neural BC1 RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:2093–2097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ule J., Darnell R. B. 2006. RNA binding proteins and the regulation of neuronal synaptic plasticity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 16:102–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang H., et al. 2005. Dendritic BC1 RNA in translational control mechanisms. J. Cell Biol. 171:811–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang H., et al. 2002. Dendritic BC1 RNA: functional role in regulation of translation initiation. J. Neurosci. 22:10232–10241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang H., Tiedge H. 2009. Dendrites: localized translation, p. 431–435. In Squire L. R., et al. (ed.), Encyclopedia of neuroscience, vol. 3 Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang H., Tiedge H. 2004. Translational control at the synapse. Neuroscientist 10:456–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhong J., et al. 2009. BC1 regulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated neuronal excitability. J. Neurosci. 29:9977–9986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhong J., et al. 2010. Regulatory BC1 RNA and the fragile X mental retardation protein: convergent functionality in brain. PLoS One 5:e15509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]