Abstract

Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors establish persistent transgene expression in the skeletal muscle of mice. How dendritic cells acquire encoded antigens for CD8+ T-cell priming is unknown. Here we document CD8+ T-cell priming after lethal irradiation and bone marrow reconstitution of mice treated with an AAV vector several weeks earlier. Temporal separation of vector delivery and successful class I antigen presentation indicated that T-cell priming does not necessarily require antigen synthesis in AAV-transduced dendritic cells. An apparent cross-presentation of antigen acquired from muscle suggests that strategies to limit transgene expression in dendritic cells will not prevent unwanted CD8+ T-cell responses.

TEXT

The delivery of recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) gene therapy vectors to muscle can result in long-term expression of transgenes that encode nonself proteins (12). CD8+ T cells targeting these proteins are maintained at low frequencies in the spleens and draining lymph nodes of mice (8, 9) but continuously infiltrate transduced muscle, where they undergo programmed death (14). Stable CD8+ T-cell frequencies can be maintained only if those that infiltrate and die in the muscle are replaced. Little is known, however, about mechanisms of class I antigen presentation and CD8+ T-cell priming after persistent transgene expression is established. Vector transduction and antigen synthesis by dendritic cells is thought to be required for CD8+ T-cell priming (2, 6, 10, 15–17). Because transduced dendritic cells have a limited life span and rAAV gene therapy vectors do not replicate or spread to new cells, this mechanism cannot satisfy an apparent requirement for ongoing antigen presentation to CD8+ T cells. Here we demonstrate that vector-transduced dendritic cells were not involved in CD8+ T-cell priming. Instead, CD8+ T cells were primed by dendritic cells that acquired antigen from rAAV-transduced muscle cells, suggesting that strategies to restrict transgene expression to nonprofessional antigen-presenting cells will not prevent T-cell immunity.

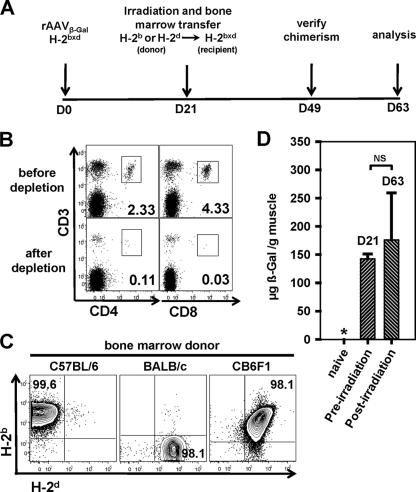

Evidence that dendritic cells cross-present antigens encoded by recombinant DNA or viral vaccine vectors was first obtained by examining patterns of CD8+ T-cell priming in mice transplanted with bone marrow that was partially mismatched at H-2 class I loci (1, 3–5). We adapted this approach to determine if dendritic cells acquire antigen from rAAV-transduced muscle to continuously prime CD8+ T cells. As shown in Fig. 1A, DNase-resistant particles (5 × 1010) of serotype 1 or 2 rAAV vectors that encode β-galactosidase (β-Gal) (rAAV1β-Gal and rAAV2β-Gal, respectively) were delivered to the quadriceps muscles of CB6F1 mice. Three weeks later, the mice were irradiated (two doses of 6 Gy separated by a 4-hour interval) and reconstituted with parental (H-2b or H-2d) bone marrow that was depleted of T lymphocytes to prevent graft-versus-host disease (Fig. 1B). Transduced myocytes of CB6F1 recipient mice express H-2b and H-2d class I molecules, but bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells, including dendritic cells, should express only parental (H-2b or H-2d) class I molecules after successful bone marrow reconstitution. Chimerism was confirmed days after the transfer of BALB/c or C57BL/6 bone marrow, when greater than 98% of mononuclear cells stained with monoclonal antibodies directed against H-2d or H-2b class I molecules, respectively (Fig. 1C, left or middle panel, respectively). Costaining with both antibodies was observed after the transfer of CB6F1 bone marrow (Fig. 1C, right panel). Very importantly, β-Gal expression persisted in muscle through lethal irradiation and bone marrow reconstitution. As an example, similar levels of β-Gal protein were detected in the muscles of CB6F1 mice 21 and 63 days after vector delivery (Fig. 1D). The later time point was 42 days after reconstitution with H-2b bone marrow, so there was no substantial loss of transduced myocytes due to lethal irradiation that might facilitate the cross-presentation of antigen.

Fig. 1.

Vector treatment and immune reconstitution. (A) Experimental timeline for vector treatment, bone marrow reconstitution, and analysis of cellular immunity. D, day. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of parental bone marrow cells before (top panels) and after (bottom panels) T-cell depletion using a cocktail of anti-CD90.2, -CD4, and -CD8 antibodies with rabbit complement. Numbers are the percentages of CD3-positive cells that coexpressed CD4 or CD8. Plots were gated on live (propidium iodide-negative) cells. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of peripheral mononuclear cells from CB6F1 mice that were reconstituted with bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 (left panel), BALB/c (middle panel), or CB6F1 (right panel) mice at day 49 (as shown on the experimental timeline in panel A), 4 weeks after lethal irradiation and bone marrow reconstitution. The cells were stained with anti-mouse H-2d and H-2b antibodies. Numbers are the percentages of cells of donor origin. (D) β-Galactosidase was quantified in muscle by an antigen-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) before (21 days after rAAV1β-Gal vector delivery) and after (63 days after rAAV1β-Gal vector delivery) bone marrow reconstitution. The asterisk indicates that the expression level was below the detection limit. The statistical difference was calculated using Student's t test. NS, not reaching statistical significance (P = 0.458). Data are results from at least 3 independent experiments.

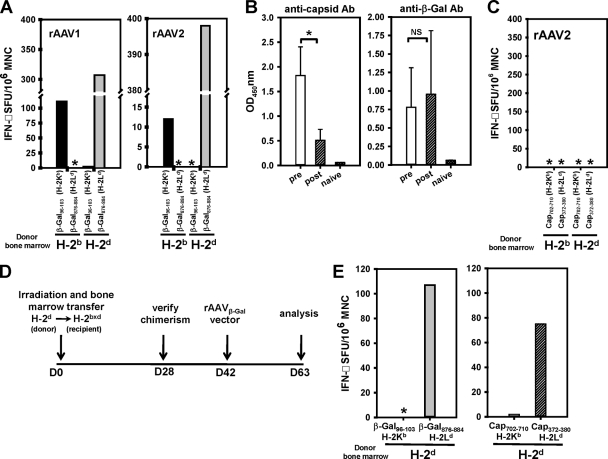

The temporal separation of rAAV vector delivery to muscle and immune system reconstitution by bone marrow transfer (Fig. 1A) was an important feature of the experimental design. The process permitted a direct test of the hypothesis that CD8+ T-cell priming occurs continuously in animals with persistent transgene expression and does not depend on antigen presentation by vector-transduced dendritic cells. CD8+ T-cell priming was assessed by a gamma interferon (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) assay after stimulation of mononuclear cells with H-2Ld- or H-2Kb-restricted β-Gal epitopes. In this model, the H-2Ld epitope (β-Gal876–884, consisting of residues 876 to 884 of β-Gal) was consistently more dominant than the H-2Kb epitope (β-Gal96–103) (Fig. 2A), but patterns of CD8+ T-cell priming and class I restriction could nonetheless be mapped in CB6F1 mice reconstituted with H-2d or H-2b bone marrow. Our observations in mice treated with the rAAV1β-Gal and rAAV2β-Gal vectors were consistent with CD8+ T-cell priming by parental dendritic cells but not by transduced F1 cells, such as myocytes. For instance, a response was detected against the H-2Ld-restricted β-Gal epitope, but not the H-2Kb-restricted epitope, in F1 mice reconstituted with H-2d bone marrow (Fig. 2A). The opposite pattern of epitope recognition was observed in animals that received the H-2b bone marrow (Fig. 2A). Mice that received autologous (H-2bxd) bone marrow responded to both epitopes, as expected (data not shown). It is unlikely that the absence of a response restricted by the mismatched parental class I molecule was due to the skewing of the T-cell repertoire, as the same pattern of responsiveness was observed in both recipient mouse strains after a reciprocal bone marrow transplantation. Moreover, T-cell repertoires appeared normal in chimeric mice used in studies of plasmid DNA vaccines (5).

Fig. 2.

Cellular and humoral immune responses in bone marrow-chimeric CB6F1 mice. (A) IFN-γ ELISpot analysis of mononuclear cells (MNC) isolated from draining lymph nodes of bone marrow-chimeric CB6F1 mice immunized previously with the rAAV1β-Gal (left panel) or rAAV2β-Gal (right panel) vector. Cells isolated from mice reconstituted with H-2b or H-2d bone marrow were stimulated in parallel with β-Gal96-103 (H-2Kb-restricted) (black bars) and β-Gal876–884 (H-2Ld-restricted) (gray bars) peptides. Asterisks indicate levels below the detection limit. SFU, spot-forming units. (B) Antibody (Ab) capture ELISA measuring serum levels of anti-capsid (left panel) and anti-β-Gal (right panel) antibodies in rAAV2β-Gal-immunized CB6F1 mice before and after bone marrow reconstitution. Open bars, prior to bone marrow reconstitution at D21; hatched bars, after bone marrow reconstitution at D63. Error bars represent standard errors of the means. Statistical difference was calculated using Student's t test. *, P = 0.001; NS, not reaching statistical significance (P = 0.706); OD450nm, optical density at 450 nm. (C) IFN-γ ELISpot analysis of mononuclear cells isolated from draining lymph nodes of bone marrow-chimeric CB6F1 mice previously immunized with rAAV2β-Gal vectors. Cells isolated from H-2b and H-2d bone marrow chimeras were stimulated with epitopic peptides derived from rAAV2 capsid, including rAAV2 cap702–710 (H-2Kb restricted) and rAAV2 cap372–380 (H-2Ld restricted). Asterisks indicate levels below the detection limit. (D) Experimental timeline for testing capsid responses in animals reconstituted with bone marrow before vector treatment. (E) IFN-γ ELISpot analysis of mononuclear cells isolated from draining lymph nodes of H-2d bone marrow-chimeric CB6F1 mice that were subsequently immunized with rAAV2β-Gal vectors. Cells were stimulated with 4 epitopic peptides in parallel, including β-Gal96–103 (H-2Kb restricted), β-Gal876–884 (H-2Ld restricted) (gray bar), rAAV2cap702–710 (H-2Kb restricted) (open bar), and rAAV2cap372–380 (H-2Ld restricted) (hatched bar). The asterisk indicates levels below the detection limit. Data are results from at least 3 independent experiments, each with cells pooled from 6 mice.

These results indicate that CD8+ T cells are primed after persistent antigen production is established with an rAAV vector, providing an explanation for how the response is maintained despite the programmed death of effector populations that infiltrate transduced muscle (14). Our failure to detect responses against both β-Gal epitopes in mice reconstituted with H-2b or H-2d bone marrow excluded the possibility that transduced F1 (H-2bxd) myocytes presented antigen directly to CD8+ T cells. For this reason, antigen presentation by myocytes that lack the capacity for costimulatory signaling cannot explain a defective CD8+ T-cell response that failed to eliminate transduced myocytes. CD8+ T cells were primed even when vector delivery to muscle preceded reconstitution of the immune system by 3 weeks. It is very unlikely that parental dendritic cells were transduced with vector particles introduced into muscle 3 weeks earlier. In support of this argument, capsid-specific antibodies present at high titers in serum after vector delivery declined substantially following irradiation and immune reconstitution, suggesting that capsid antigens were not available to regenerate the response (Fig. 2B, left panel). Antibodies to β-Gal were maintained before and after immune reconstitution, reflecting the persistence of antigen expression in muscle (Fig. 2B, right panel). Moreover, T-cell responses against two well-defined AAV capsid epitopes presented by H-2Kb (capsid with amino acids 702 to 710 [cap702-710]) and H-2Ld (cap372-380) class I molecules were not detected in F1 mice after reconstitution with H-2b or H-2d bone marrow (Fig. 2C). Capsid-specific CD8+ T-cell responses were readily generated when an H-2d immune system was transferred to F1 mice before vector delivery (Fig. 2D and E). CD8+ T-cell responses were detected against the H-2d- but not the H-2b-restricted β-Gal (Fig. 2E, left panel) and capsid (Fig. 2E, right panel) epitopes. The opposite pattern of capsid-specific CD8+ T-cell reactivity was observed after H-2b bone marrow reconstitution (data not shown). These results are consistent with a requirement for dendritic cells to generate a response to particle-associated capsid proteins (11, 13).

Intramuscular delivery of rAAV1β-Gal and rAAV2β-Gal induced CD8+ T-cell responses, even though the latter vector is thought to transduce dendritic cells inefficiently (7, 13). Indeed, direct transduction of dendritic cells by rAAV vectors was not required for T-cell priming once persistent antigen expression was established in this model. The pattern of CD8+ T-cell priming in bone marrow-reconstituted F1 mice is best explained by dendritic cell cross-presentation of antigen acquired from rAAV1β-Gal- and rAAV2β-Gal-transduced myocytes. Our observations also indicate that the use of cell-type-specific promoters that permit transgene expression in myocytes, but not dendritic cells, is unlikely to prevent CD8+ T-cell priming, as was previously proposed (2). Finally, the model described here may be generally useful to identify the defects in antigen presentation that reinforce priming of an ineffective CD8+ T-cell response and may be important for successful gene therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian K. Kaspar for kindly providing us with the rAAV1β-Gal vector and David V. Schaffer for his collaborative efforts toward the completion of this study. We are also grateful for Melinda A. Chanley's technical assistance with animal care.

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants R01AI60388-5 to C.M.W. and 5R01HL081527-02 to David V. Schaffer and C.M.W.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 August 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bassett J. D., et al. 2011. CD8+ T-cell expansion and maintenance after recombinant adenovirus immunization rely upon cooperation between hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic antigen-presenting cells. Blood 117: 1146–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cordier L., et al. 2001. Muscle-specific promoters may be necessary for adeno-associated virus-mediated gene transfer in the treatment of muscular dystrophies. Hum. Gene Ther. 12: 205–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Corr M., Lee D. J., Carson D. A., Tighe H. 1996. Gene vaccination with naked plasmid DNA: mechanism of CTL priming. J. Exp. Med. 184: 1555–1560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Doe B., Selby M., Barnett S., Baenziger J., Walker C. M. 1996. Induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes by intramuscular immunization with plasmid DNA is facilitated by bone marrow-derived cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93: 8578–8583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fu T. M., et al. 1997. Priming of cytotoxic T lymphocytes by DNA vaccines: requirement for professional antigen presenting cells and evidence for antigen transfer from myocytes. Mol. Med. 3: 362–371 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jooss K., Yang Y., Fisher K. J., Wilson J. M. 1998. Transduction of dendritic cells by DNA viral vectors directs the immune response to transgene products in muscle fibers. J. Virol. 72: 4212–4223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li C., et al. 2007. Adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) capsid-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes eliminate only vector-transduced cells coexpressing the AAV2 capsid in vivo. J. Virol. 81: 7540–7547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lin J., Zhi Y., Mays L., Wilson J. M. 2007. Vaccines based on novel adeno-associated virus vectors elicit aberrant CD8+ T-cell responses in mice. J. Virol. 81: 11840–11849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lin S. W., Hensley S. E., Tatsis N., Lasaro M. O., Ertl H. C. 2007. Recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors induce functionally impaired transgene product-specific CD8+ T cells in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 117: 3958–3970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lu Y., Song S. 2009. Distinct immune responses to transgene products from rAAV1 and rAAV8 vectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106: 17158–17162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mays L. E., et al. 2009. Adeno-associated virus capsid structure drives CD4-dependent CD8+ T cell response to vector encoded proteins. J. Immunol. 182: 6051–6060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mays L. E., Wilson J. M. 2011. The complex and evolving story of T cell activation to AAV vector-encoded transgene products. Mol. Ther. 19: 16–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vandenberghe L. H., et al. 2006. Heparin binding directs activation of T cells against adeno-associated virus serotype 2 capsid. Nat. Med. 12: 967–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Velazquez V. M., Bowen D. G., Walker C. M. 2009. Silencing of T lymphocytes by antigen-driven programmed death in recombinant adeno-associated virus vector-mediated gene therapy. Blood 113: 538–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xin K.-Q., et al. 2006. Induction of robust immune responses against human immunodeficiency virus is supported by the inherent tropism of adeno-associated virus type 5 for dendritic cells. J. Virol. 80: 11899–11910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang Y., Chirmule N., Gao G.-P., Wilson J. 2000. CD40 ligand-dependent activation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes by adeno-associated virus vectors in vivo: role of immature dendritic cells. J. Virol. 74: 8003–8010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ziegler R. J., et al. 2004. AAV2 vector harboring a liver-restricted promoter facilitates sustained expression of therapeutic levels of alpha-galactosidase A and the induction of immune tolerance in Fabry mice. Mol. Ther. 9: 231–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]