Abstract

While human leukocyte antigen B57 (HLA-B57) is associated with the spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus (HCV), the mechanisms behind this control remain unclear. Immunodominant CD8+ T cell responses against the B57-restricted epitopes comprised of residues 2629 to 2637 of nonstructural protein 5B (NS5B2629–2637) (KSKKTPMGF) and E2541–549 (NTRPPLGNW) were recently shown to be crucial in the control of HCV infection. Here, we investigated whether the selection of deleterious cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) escape mutations in the NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope might impair viral replication and contribute to the B57-mediated control of HCV. Common CTL escape mutations in this epitope were identified from a cohort of 374 HCV genotype 1a-infected subjects, and their impact on HCV replication assessed using a transient HCV replicon system. We demonstrate that while escape mutations at residue 2633 (position 5) of the epitope had little or no impact on HCV replication in vitro, mutations at residue 2629 (position 1) substantially impaired replication. Notably, the deleterious mutations at position 2629 were tightly linked in vivo to upstream mutations at residue 2626, which functioned to restore the replicative defects imparted by the deleterious escape mutations. These data suggest that the selection of costly escape mutations within the immunodominant NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope may contribute in part to the control of HCV replication in B57-positive individuals and that persistence of HCV in B57-positive individuals may involve the development of specific secondary compensatory mutations. These findings are reminiscent of the selection of deleterious CTL escape and compensatory mutations by HLA-B57 in HIV-1 infection and, thus, may suggest a common mechanism by which alleles like HLA-B57 mediate protection against these highly variable pathogens.

INTRODUCTION

Although the mechanisms of spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus (HCV) remain poorly understood, the carriage of certain human leukocyte antigen class I (HLA-I) alleles, such as HLA-A03, -A11, -B27, -B57, and -Cw01, has been strongly associated with viral control (22, 31, 35, 45). HLA class I alleles function to present virally derived peptides to circulating CD8+ T cells, which have been independently shown to play a critical role in the control and clearance of HCV infections (24, 44). However, the ability of HCV to frequently evade these responses through the development of cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) escape mutations represents an important mechanism contributing to HCV persistence (11, 43, 46).

Interestingly, certain HLA alleles, such as HLA-B57 and -B27, have been associated with the control of both HCV and HIV type 1 (HIV-1) infections, suggesting a possible shared mechanism of control of highly variable pathogens (1, 2, 9, 17, 33, 35). In the case of HIV-1, these alleles are associated with the targeting of highly conserved regions of the virus by CD8+ T cell responses, whereupon viral escape leads to the selection of deleterious mutations which substantially impair viral replication capacity (30, 34). Moreover, CTL escape from these responses is unique in that it requires the development of secondary compensatory mutations which function to restore the severe impact of the primary mutations on replication capacity (6, 12, 40). In the case of HLA-B27, this strict requirement for compensation results in the inability of HIV-1 to escape from this response until many years after infection (18, 40). Thus, the selection of mutations that impair viral fitness contributes, in part, to the propensity of HLA-B57 and -B27 to control a highly variable pathogen like HIV-1.

In HCV infection, thus far, only a few studies have addressed the impact of CTL escape mutations on the replication capacity of HCV (13, 39, 42, 50). Limitations on research in this area have been imposed by two major factors: the lack of a robust cell culture system for the most prevalent genotypes of HCV (genotypes 1a and 1b) and limited knowledge of HLA-I-associated viral polymorphisms. Recent efforts to characterize the adaptation of HCV to host immune responses have now significantly increased our knowledge of the location and frequency of CTL escape mutations across the HCV proteome (15, 16, 37, 38, 47). This has opened new avenues to study the influence of CTL escape mutations on HCV replication fitness and their possible contribution to the control of HCV. Although robust cell culture systems for genotypes 1a and 1b of HCV are not yet available, corresponding replicon systems have proven very useful in addressing the impact of drug resistance mutations on HCV replicative fitness (20, 25, 26, 29, 48, 52) and, thus, can be applied to study the influence of CTL escape mutations on HCV.

In a recent study by Kim et al. (21), immunodominant CD8+ T cell responses toward the HLA-B57-restricted epitopes comprised of residues 2629 to 2637 of nonstructural protein 5B (NS5B2629–2637) (KSKKTPMGF) and E2541–549 (NTRPPLGNW) were shown to be associated with the control of HCV. To investigate whether this control might be mediated through the selection of uniquely deleterious CTL escape mutations, we examined the impact of immune-selected mutations in the NS5B polymerase epitope on HCV replication in a transient replicon system. Our results demonstrate that CTL escape mutations in the NS5B2629-2637 (KSKKTPMGF) epitope can substantially impair HCV replication in vitro and that these defects can be restored in vivo through the development of unique compensatory mutations in patients with persistent HCV infection. These data suggest that the selection of deleterious CTL escape mutations may play a role in the initial control of HCV by HLA-B57 and that, in some individuals, this protective effect can be mitigated through compensatory mutations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and viral sequences.

Full-length HCV genome sequence data were derived from 374 patients with chronic genotype 1a HCV infection as previously described (23). All subjects gave informed consent to participate in an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocol at each institution.

Construction of a subgenomic replicon chimera and point mutant replicons.

The HCV genotype 1b subgenomic replicon construct I341PILuc_ns3_3ET (14) was modified to generate a chimera expressing the polymerase gene of HCV genotype 1a strain H77 (GenBank accession number M67463). Primers 5′-CTCCAAGCGGAGGAGGATG-3′ (nucleotides [nt] 7020 to 7038) and 5′-CATGATCCCCCATGTTGTG-3′ (nt 10200 to 10219) were used to amplify the fragment located within the XhoI and PvuI restriction sites (nt 7080 to 10180) from I341PILuc_ns3_3ET. An intermediate vector was generated by subcloning the amplified fragment into the commercially available vector pCR4.topo (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Mutagenesis was then performed on the intermediate vector using a QuikChange Lightning site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to remove a recognition site for BamHI (substitution A to G at nt 7381 in I341PILuc_ns3_3ET) and to create a recognition site for AgeI (substitution A to G at nt 9275) using primer pairs 5′-GACGGCGACGCGGGGTCCGACGTTGAGTC-3′ and 5′-GACTCAACGTCGGACCCCGCGTCGCCGTC-3′ and 5′-CATCTATCTACTCCCCAACCGGTGAACGGGGAGCTAAACACTC-3′ and 5′-GAGTGTTTAGCTCCCCGTTCACCGGTTGGGGAGTAGATAGATG-3′, respectively. Mutated nucleotides are highlighted in bold, and unchanged amino acid residues are underlined. Note, during the cloning of the H77 polymerase gene into the Con1 backbone, the last 23 amino acids of NS5A were transferred along with NS5B, since an endonuclease restriction site between NS5A and NS5B of both Con1 and H77 was not available. This region contains 3 amino acid polymorphisms (residues 2410, 2411, and 2413) between the two strains, in addition to a threonine insertion at residue 2414 (T2414) (see Fig. 3A). The gene encoding HCV genotype 1a polymerase was amplified from the H/FL plasmid (5) with Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using primers 5′-GGAGCCTGGGGATCCGGATC-3′ and 5′-CCTTCACCGGTTGGGGAGGAGG-3′ (recognition sites for BamHI and AgeI are underlined). This fragment was then subcloned into the intermediate vector cut with BamHI and AgeI (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA), resulting in the generation of a chimeric intermediate vector. Finally, we generated the chimeric subgenomic replicon by transferring the XhoI-PvuI fragment from the chimeric intermediate vector into the I341PILuc_ns3_3ET plasmid restricted with XhoI and PvuI (New England BioLabs). The resulting plasmid, termed the Con1/H77 chimera, was then confirmed by sequencing its complete NS5B and NS3 genes. To generate Con1/H77 variants, CTL escape mutations were engineered into the chimeric intermediate vector using a QuikChange Lightning site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Mutated NS5B regions were confirmed by DNA sequencing and then back cloned into Con1/H77 using XhoI and BglII (New England BioLabs), with the final constructs confirmed through additional sequencing.

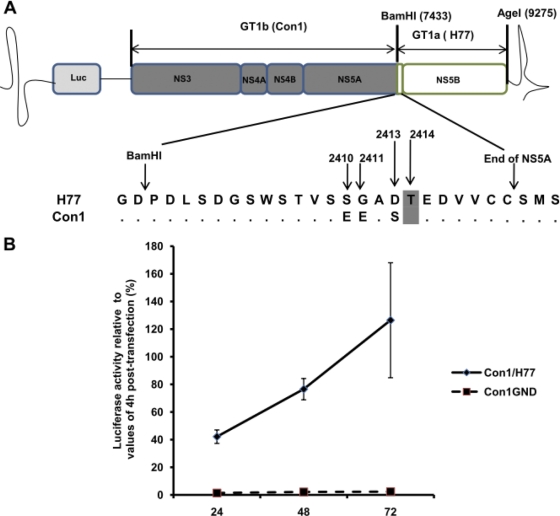

Fig. 3.

Structure and replication ability of the transient chimeric Con1/H77 replicon system. (A) The chimeric replicon Con1/H77 (genotype 1b) construct was generated by swapping the polymerase gene of the subgenomic replicon construct I341PILuc_ns3_3ET with the polymerase gene of the H77 (genotype 1a) strain. HCV genes derived from I341PILuc_ns3_3ET are depicted in gray, and the one derived from H77 is depicted in white. Restriction sites used for cloning strategy are shown. During cloning of H77, the last 23 amino acids of NS5A were also transferred; this sequence contains 3 amino acid polymorphisms (2410, 2411, and 2413) between Con1 and H77, in addition to a threonine insertion at residue 2414 (T2414), which is highlighted in gray. Luc, luciferase. (B) The replication of the Con/H77 chimera was assessed in Huh7-Lunet cells and was compared to that of Con1GND (replication-defective mutant of Con1). Replication efficiency is represented as relative luciferase activity calculated by normalizing values of luciferase at 24, 48, and 72 h to values of luciferase at 4 h after transfection. Error bars represent the standard deviations of the relative luciferase activities from 3 independent experiments at 24, 48, and 72 h after transfection.

Cell lines and cell culture.

Huh7-Lunet cells (27) were cultivated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco-BRL/Invitrogen), nonessential amino acids (Gibco-BRL/Invitrogen), 100 U penicillin per ml, 100 μg streptomycin per ml (Gibco-BRL), 10 mM HEPES buffer (Mediatech Cellgro, Manassas, VA), and 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum (Sigma-Aldrich).

RNA synthesis.

Con1/H77 and the derivate mutant plasmids were linearized using PvuI and ScaI (New England BioLabs). Linearized plasmids were purified by phenol (Ambion, Austin, TX) and chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich) treatment and then precipitated in isopropanol (Sigma-Aldrich). Aliquots of linearized DNA were prepared in diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water, and 1 μg of the purified plasmid was used as a template for synthesis of RNA by in vitro transcription using a MEGAscript T7 high-yield transcription kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The resulting RNA was purified by TRIzol (Invitrogen) treatment, precipitated in isopropanol, and dissolved in DEPC-treated water (Ambion).

Transfection and replication assays.

Huh7-Lunet cells were transfected as previously described (27). Briefly, 4 × 106 cells were suspended in Cytomix, mixed with 5 μg of in vitro-transcribed replicon RNA, and then pulsed at 270 V, 950 μF, and 100 Ω with the Gene Pulser Xcell apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Transfected cells were suspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, nonessential amino acids, 100 U penicillin per ml, 100 μg streptomycin per ml, 10 mM HEPES buffer, and 10% fetal calf serum) and then seeded onto 6-well plates. Luciferase activity was assayed at 4 and 48 h after transfection in the lysates of transfected cells by using the Steadylite plus luminescence reporter gene assay system (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT) with the microplate scintillation and luminescence counter Top Count NTX (PerkinElmer). Replication relative to that of the wild type (WT) was calculated by normalizing the relative luciferase activity (48 h/4 h) of each construct to that of the parental Con1/H77 chimeric replicon (set as 100%).

Polyclonal antigen-specific expansion of T cells.

A peptide-specific T cell line specific to the NS5B2629–2637 epitope was expanded using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from an HLA-B57-positive (HLA-B57+) individual chronically infected with HCV GT1a. Responses were measured by gamma interferon (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay (ELISpot) assay and considered positive if the number of spots per well minus the background was >50 spot-forming cells (SFC)/106 PBMC, with a background of <15 SFC/106 PBMC. Any response yielding 400 or more spots per well was set as a maximal response. To determine the impact of specific mutations on T cell recognition, responses were measured against log10 dilutions of both WT and variant peptides. Decreased recognition was defined as a greater-than-2-fold reduction in the ELISpot response at two or more concentrations of the variant peptide (11). Phytohemagglutinin (PHA) was used as a positive control.

Structure analysis.

Analysis of the structural interaction between residues 2626 and 2629 within the HLA-B57 epitope KSKKTPMGF of strain H77 (GenBank accession number M67463) was performed using PyMol (www.pymol.org).

Statistical analysis.

HLA-B57-associated sequence polymorphisms were identified using Fisher's exact test. The significance of any increase or decrease in replicon fitness conferred by mutation(s) was calculated using Student's t test, with a P value of <0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

CTL escape from the immunodominant HLA-B57-restricted NS5B2629–2637 epitope.

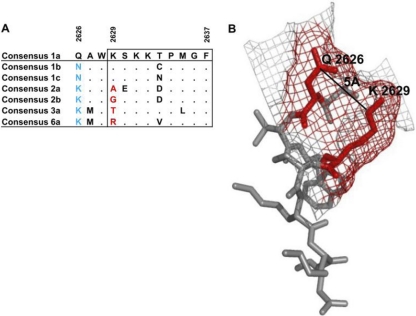

The ability of HCV to escape responses mediated by HLA-B57 was previously addressed in a small cohort of patients (21). To extend this work and to more broadly examine viral sequence diversity in the immunodominant NS5B2629–2637 (KSKKTPMGF) epitope, we took advantage of a larger cohort of patients and sequenced 374 NS5B genes derived from individuals infected with genotype 1a (23). Analysis of the sequence data revealed five polymorphic residues, with mutations at position 1 (2629) and position 5 (2633) of the epitope predominating in HLA-B57-positive subjects (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Three distinct variants (K2629N/Q/S) arose at position 1 and were significantly associated with the expression of HLA-B57 (odds ratio [OR] = 16.73; P = 0.0001) (Table 1), with substitution K2629N representing the major variant. Mutations at position 5, where four different variants (T2633A/S/V/N) were observed, were also significantly associated with the expression of the HLA-B57 allele (OR = 5; P = 0.0055) (Table 1). Notably, mutations at residues 2629 and 2633 were mutually exclusive, with no double 2629/2633 mutations observed in any of the 374 sequences examined (Fig. 1). Taken together, these data support the strong selection of specific mutations in the NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope in HLA-B57-positive subjects.

Fig. 1.

Identification of HLA-B57-associated mutations in the B57-restricted NS5B epitope KSKKTPMGF. Viral sequences derived from 18 HLA-B57-positive individuals and 356 HLA-B57-negative individuals were aligned against a consensus HCV genotype 1a sequence to identify polymorphisms within the HLA-B57-restricted epitope KSKKTPMGF. Dots represent sequence similarity between the reference sequence and patient's derived sequences, while letters denote amino acid differences. Mutations at position 1 are highlighted in red, while those at position 5 are highlighted in green, and the frequency of each viral variant is shown.

Table 1.

Mutations within the HLA-B57-restricted epitope NS5B2629-2633 are significantly associated with the carriage of an HLA-B57 allele

| HLA-B57 status of subjects | No. of subjects with polymorphism at indicated NS5B2629-2633 epitope residue(s)/total no. of subjects (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| K2629X | T2633X | Residue 2629 to 2637 windowa | |

| HLA-B57+ | 5/18 (28) | 6/18 (33) | 11/18 (61) |

| HLA-B57− | 8/356 (2) | 32/356 (9) | 38/356 (10) |

| Total | 13/374 (3) | 38/374 (10) | 49/374 (13) |

| ORb | 17 | 5 | 13 |

| P value | 0.0001 | 0.0055 | 0.0001 |

Polymorphism is exhibited across the KSKKTPMGF epitope.

Odds ratio for the association of mutations at positions 2629 and 2633 with the expression of HLA-B57. A positive odds ratio indicates the selection of mutations in the presence of HLA-B57.

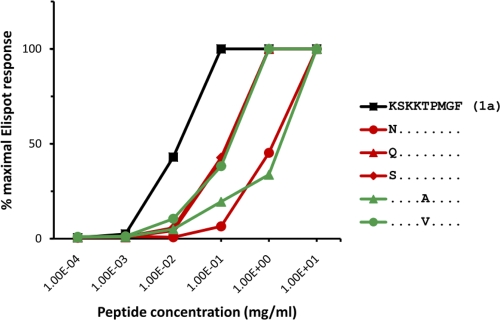

HLA-B57-associated mutations in the NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope impair T cell recognition.

We next investigated whether any of the mutations at position 1 (2629) and position 5 (2633) of the NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope impaired CD8+ T cell recognition. To accomplish this, an NS5B KSKKTPMGF-specific T cell line was derived from an individual chronically infected with genotype 1a and the impacts of the dominant mutations at positions 2629 and 2633 on T cell recognition were assessed using an IFN-γ ELISpot assay. Variant peptides containing mutations K2629N and T2633A were found to exhibit the greatest impact on T cell recognition (Fig. 2). Notably, these represented the most frequently observed mutations in HLA-B57-positive individuals. Responses against three other common variants (K2629Q, K2629S, and T2633V) were also impaired, though to a lesser degree. These data extend our previous findings (21), which illustrated similarly impaired recognition of the K2629N escape variant, as well as the T2633A and T2633V escape variants, in a second independent subject. Indeed, these three mutations represented the most poorly recognized variants in each of the assays and illustrate that these mutations represent highly effective escape mutations in two different HLA-B57+ subjects. These data also now support that the majority of CTL escape mutations arising in the NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope convey T cell escape. Therefore, each of the predominant B57-associated mutations in the NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope impaired CD8+ T cell recognition, revealing various abilities to impair T cell recognition.

Fig. 2.

Impact of CTL escape mutations on CD8+ T cell recognition. A CD8+ T cell line specific for the NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope was tested for recognition of the wild-type and variant peptides. Peptide titration curves illustrate the different impacts of the predominant CTL escape mutations on T cell recognition.

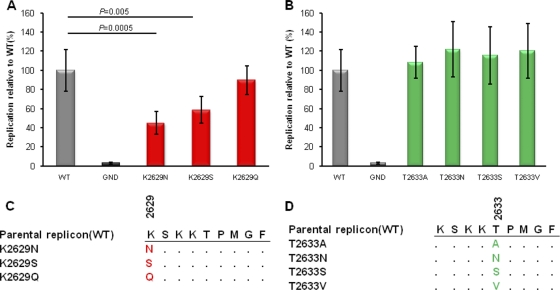

CTL escape mutations in the NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope impair viral replication capacity.

Since various studies have illustrated the impact of specific drug resistance mutations on viral replication using the replicon system (28), we next sought to examine the impact of HLA-B57-associated escape mutations on replication capacity. Since a transient replicon system for HCV genotype 1a is not yet available and the use of genotype 1a selectable replicon systems could limit the ability to accurately quantify the impact of mutations on HCV replication, we generated a chimeric transient replicon expressing the polymerase of HCV genotype 1a in the background of the Con1 (genotype 1b) replicon to quantify the impact of these genotype 1a-specific NS5B mutations. To accomplish this, we replaced the polymerase gene of Con1 (genotype 1b) with the corresponding gene of H77 (genotype 1a) (Fig. 3A). As shown in Fig. 3B, the chimeric replicon was capable of effectively replicating in Huh7-Lunet cells, exhibiting only a 3- to 4-fold-lower level of replication than the parental Con1 replicon (data not shown). We then individually engineered each of the position 1 (K2629N/Q/S) and position 5 (T2633A/S/V/N) mutations into the chimera Con1/H77 replicon and assessed their relative levels of replication. Notably, while mutations at position 2633 had no significant impact on the replication of the Con1/H77 replicon, mutations K2629N and K2629S significantly impaired replication, to 45% and 59%, respectively, of the WT level (Fig. 4A and 4B). The third mutation, K2629Q, exhibited a small decrease in replication (89.93% of the WT level), although this was not statistically significant (P = 0.52). Taken together, these data suggest that mutations at position 1 (residue 2629) of the NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope substantially impair replication of HCV. These data are supported by their near absence in vivo in viruses derived from subjects who do not express HLA-B57.

Fig. 4.

Replication capacities of variant replicons compared to that of the parental Con1/H77 chimera. Replication of each of the variant constructs containing the CTL escape mutations. Relative luciferase activity (48 h/4 h) of each construct was calculated by normalizing to that of the parental Con1/H77 chimeric replicon (set as 100%). Error bars represent the standard deviations of the relative luciferase activities from 6 independent experiments. P values were calculated using Student's t test to compare the relative luciferase activity of each mutant to that of the wild type (WT). (A) Replication of K2629X mutants. (B) Replication of T2633X mutants. (C) Sequence alignment of K2629X mutants. (D) Sequence alignment of K2633X mutants. GND represents a replication-defective mutant of the parental replicon Con1.

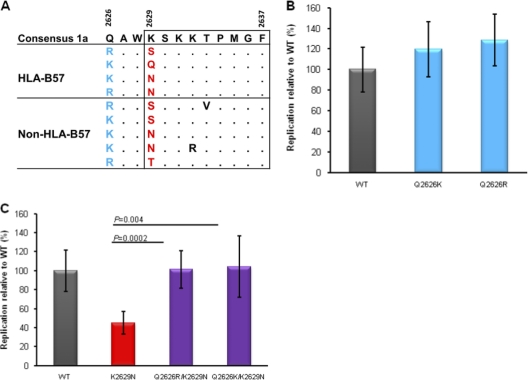

Compensatory mutations restore the replication defects of mutations K2629N/S.

The presence of these deleterious CTL escape mutations at position 1 (2629) of the NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope in circulating strains of HCV (Fig. 1) raised the possibility that secondary compensatory mutations, functioning to restore these replicative defects, might be required (6, 12, 40). Examination of patient-derived sequences flanking the NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope revealed the presence of mutations at residue 2626 tightly linked to mutations at residue 2629, notably in both B57-positive and B57-negative subjects (P = 0.0001) (Fig. 5A). Notably, loss of the positively charged lysine residue at position 2629 in the epitope was consistently accompanied by replacement with a positive charged arginine or lysine residue at position 2626. As such, we hypothesized that mutations at residue 2626 might restore the substantial replicative defects of mutations at residue 2629. To test this hypothesis, variant replicons bearing the mutation Q2626K or Q2626R, alone or in combination with the predominant K2629N escape mutation, were generated and tested for replication efficiency. When tested alone, mutation Q2626K or Q2626R slightly improved the replication of Con1/H77 (P = 0.25 and P = 0.095, respectively) (Fig. 5B). Importantly, however, coexpression of Q2626K or Q2626R in combination with the predominant K2629N mutation significantly restored the replication defect of K2629N, to near wild-type levels (P = 0.004 and P = 0.0002, respectively) (Fig. 5C), supporting the role of polymorphisms at residue 2626 functioning as compensatory mutations.

Fig. 5.

Coevolution of mutations at residues 2626 and 2629 of HCV polymerase and their effect on the replicon. Alignment of viral sequences flanking the NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope reveals coevolution of sequence polymorphisms at residues 2626 and 2629. (A) All patient-derived sequences exhibiting polymorphisms at residues 2626 and 2629 are shown, with those derived from HLA-B57-positive subjects at the top and those of B57-negative individuals at the bottom. Mutations distinct from the consensus genotype 1a are shown, with dots representing sequence similarity to the consensus sequence. Amino acids at residue 2626 are highlighted in blue, while amino acids at residue 2629 are highlighted in red. (B) Replication capacities of replicon variants bearing substitution Q2626K or Q2626R alone relative to that of the parental Con1/H77 construct (WT). (C) Replication capacities of replicon variants bearing substitutions K2629N, Q2626R/K2629N, and Q2626K/K2629N. Error bars represent the standard deviations of relative luciferase values from 6 independent experiments.

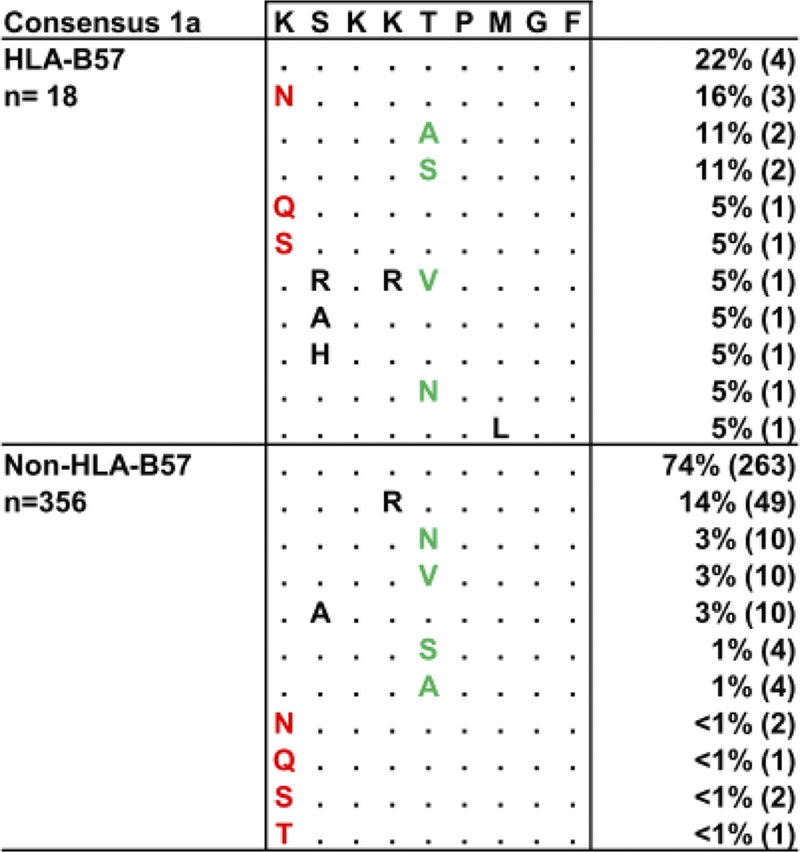

Interestingly, analysis of the consensus sequences of other HCV genotypes illustrated that residues 2626 and 2629 strongly coevolve, with a requirement of maintenance of a mutually exclusive positively charged amino acid at either position 2626 or 2629 (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, a structural analysis of this region of the polymerase protein revealed that the distance between the side chains of residues Q2626 and K2629 was less than 5Å, supporting the requirement for the tight coevolution of these two residues (Fig. 6B). Taken together, these data suggest that the maintenance of a positive charge in this region of NS5B is critical for the interaction of the polymerase protein with HCV RNA or an unknown host protein required for the optimal replication of HCV. Overall, 39% (7/18) of sequences derived from B57-positive individuals expressed mutations Q2626K/R, with 57% (4/7) associated with mutations at K2629. In contrast, only 15% (53/356) of sequences derived from B57-negative individuals expressed mutations Q2626K/R, with 9% (5/53) associated with mutations at K2629. The relatively low frequency of the Q2626K/R mutations in the absence of HLA-B57 is suggestive of initial selection for mutations at K2629 followed by compensation through mutations at Q2626.

Fig. 6.

Structural analysis of the interaction between costly CTL escape and compensatory mutations. (A) Alignment of viral sequences flanking the NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope reveals the coevolution of residues 2626 and 2629 among different genotypes of HCV. Note the requirement for a positively charged and a neutral amino acid at 2626 and 2629 across different genotypes. (B) Depicted in gray is the region of amino acids 2626 to 2638 of the polymerase of H77 strain. Amino acid residues Q2626 and K2629 are highlighted in red. As indicated, the distance between the side chains of the two residues is less than 5 Å. The web structure depicted in red highlights the localization of Q2626 and K2629 on the surface of the polymerase of strain H77.

DISCUSSION

HLA-B57 has been strongly associated with the control of both HIV-1 and HCV (1, 9, 10, 32). The mechanisms for such control still remain unclear; however, it is likely that CD8+ T cell responses play a crucial role in that process (44). Recently, CD8+ T cell responses against the immunodominant B57-restricted epitopes in polymerase (NS5B) and envelope (E2) of HCV were shown to be associated with spontaneous clearance of HCV genotype 1a (21). Our data extend these findings to suggest that the ability of the NS5B-specific CD8+ T cell response to select for highly deleterious escape mutations may contribute to the immune-mediated control of HCV exhibited in B57-positive subjects infected with HCV genotype 1a. Furthermore, the ability of HCV to in some cases compensate for the fitness cost of these mutations may contribute to persistence of HCV in a portion of HLA-B57-positive subjects.

While multiple amino acid substitutions were observed within the NS5B KKKTPMGF epitope in circulating strains from HLA-B57-negative subjects, the majority of these were notably found to be HLA-B57-associated mutations restricted to residues 2629 and 2633. This suggests that selection upon this conserved region of NS5B may be predominantly mediated by HLA-B57. Interestingly, however, the HLA-B57-associated polymorphisms at residues 2629 and 2633 were found to be mutually exclusive. Ueno and colleagues recently reported a similar phenomenon in an HLA-A24-restricted epitope in HIV-1 Nef, where mutually exclusive CTL escape mutations within this epitope significantly impaired HIV-1 replication when coexpressed (51). Thus, our data may suggest strong structural constraints against viral evolution within this region of HCV polymerase. This phenomenon of multiple escape pathways within a targeted HCV CD8 epitope is reminiscent of CTL escape in the HLA-B27-restricted epitope AF9 (ARMILMTHF2841–2849) in NS5B, a response believed to be critical to the immune control of HCV associated with HLA-B27 (35). Thus, complex CTL escape patterns may be more broadly indicative of the inability of certain regions of the virus to effectively escape from strong selection pressures, with no single CTL escape mutation being uniquely effective at evading the immune response without a substantial cost to viral replication. This appears in stark contrast to viral escape in the commonly targeted HLA-A01-restricted epitope AY9 (ATDALMTGY1436–1444) in NS3, where viral escape occurs nearly uniformly through a single C-terminal Y1444F anchor mutation (47).

To assess the impact of genotype 1a-specific CTL escape mutations on viral fitness, we developed a Con1/H77 (1b/1a) replicon chimera, since a transient replicon-based assay for genotype 1a was not available. Other chimeric HCV replicons have been successfully generated (4, 19, 29) and used to study replicative properties of HCV, as well as to assess the impact of antiviral compounds. Our genotype 1b/1a NS5B chimera was found to replicate robustly and was suitable to distinguish the impact of the various mutations in the NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope, as well as the ability of mutations at position 2626 to restore these replication defects. Our results indicate that HLA-B57-associated mutations at residue 2629 substantially impair the replication of the replicon. Thus far, only a few studies have addressed the impact of CTL escape mutations in HCV infection on viral fitness, including mutations in the B08-HL9 (HSKKKCDEL1359–1367) and B27-AF9 (ARMILMTHF2841–2849) epitopes (13, 39). Notably, CTL escape mutations in the B08 epitope were substantially less frequently selected and appeared to impair replication to a lesser degree than those observed here, which may account for the lack of association of HLA-B08 with clearance. Thus, a growing number of studies now support the ability of immune-selected mutations in HCV to incur an impact on viral fitness, suggesting a possible role for such mutations in the ability of some HLA alleles to mediate control.

A growing body of literature now supports the ability of some CTL escape mutations in HIV-1 infection to impair viral replication. HLA-B57- and -B27-associated CTL escape mutations in the HIV-1 Gag protein (6, 30, 41) in particular have been found to impair viral replication to a greater degree than CTL escape mutations restricted by other HLA alleles (8, 49). Moreover, those deleterious escape mutations have been linked to the requirement for compensatory mutations that rescue these substantial replicative defects (3, 7, 40). In the context of infection with HCV, however, compensatory mutations to commonly described CTL escape mutations have not yet been reported. Our description of viral escape and compensation in the NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope suggests that strong CTL pressures against HCV can also select for highly deleterious CTL escape mutations that require compensatory mutations. Notably, we have also now observed the requirement for compensatory mutations to facilitate escape from an HLA-B27-restricted response in HCV polymerase (36a). However, it is important to note that mutations at position 2629 already predominate in genotypes 2a, 2b, 3a, and 6a, which might suggest that the protective effect of HLA-B57 could be genotype specific. This interpretation would be in line with recent reports of genotype-dependent effects on the HLA-mediated control of HCV (21, 22, 36). A recent study by Chuang et al. (9) indicates the protective effect of HLA-B57 on the control of HCV genotype 2 infections, which could therefore suggest that in genotype 2 infections, the K2629A variant (not tested here) is capable of being recognized or that this protective effect is not related to the targeting of the NS5B KSKKTPMGF epitope. Taken together, these data suggest that fitness costs associated with CTL escape may also contribute importantly to the control of HCV mediated by alleles such as HLA-B57 and -B27 and support an important role of CD8+ T cells immunodominantly targeting critical epitopes such as the B57 KSKKTPMGF epitope in NS5B.

In conclusion, we have shown that CD8+ T cell-mediated escape mutations in a dominant HLA-B57-restricted epitope located in HCV polymerase substantially impair HCV replication. The observation that the deleterious effects of those mutations can be reversed through the development of compensatory mutations suggests a possible mechanism of persistence in some B57-positive individuals. Understanding the mechanisms by which particular CD8+ T cell responses mediate control of HCV is important to the design of an effective HCV vaccine capable of recapitulating these protective effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was funded in part with federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) under grants R01-AI067926 (T.M.A.), U19-AI066345 (T.M.A. and G.M.L.), and U19-AI082630 (T.M.A. and G.M.L.).

We thank R. Bartenschlager (University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany) for providing plasmids H77/JFH-1(C3) and I341PILuc_ns3_3ET, as well as Huh7-Lunet cells, and Charles Rice (Rockefeller University, New York City, NY) for providing Huh7.5 cells and the H77 (H/FL) plasmid. We also thank the study subjects for their participation in the study, clinical collaborators for sample collection, and the collaborators at the Broad Institute who conducted the virus sequencing.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 August 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Altfeld M., et al. 2003. Influence of HLA-B57 on clinical presentation and viral control during acute HIV-1 infection. AIDS 17: 2581–2591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Altfeld M., et al. 2006. HLA alleles associated with delayed progression to AIDS contribute strongly to the initial CD8(+) T cell response against HIV-1. PLoS Med. 3: e403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bailey J. R., Williams T. M., Siliciano R. F., Blankson J. N. 2006. Maintenance of viral suppression in HIV-1-infected HLA-B*57+ elite suppressors despite CTL escape mutations. J. Exp. Med. 203: 1357–1369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Binder M., et al. 2007. Identification of determinants involved in initiation of hepatitis C virus RNA synthesis by using intergenotypic replicase chimeras. J. Virol. 81: 5270–5283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blight K. J., McKeating J. A., Marcotrigiano J., Rice C. M. 2003. Efficient replication of hepatitis C virus genotype 1a RNAs in cell culture. J. Virol. 77: 3181–3190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brockman M. A., et al. 2007. Escape and compensation from early HLA-B57-mediated cytotoxic T-lymphocyte pressure on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag alter capsid interactions with cyclophilin A. J. Virol. 81: 12608–12618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chopera D. R., et al. 2008. Transmission of HIV-1 CTL escape variants provides HLA mismatched recipients with a survival advantage. PLoS Pathog. 4.e1000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Christie N. M., et al. 2009. Viral fitness implications of variation within an immunodominant CD8+ T-cell epitope of HIV-1. Virology 388: 137–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chuang W. C., et al. 2007. Protective effect of HLA-B57 on HCV genotype 2 infection in a West African population. J. Med. Virol. 79: 724–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Costello C., et al. 1999. HLA-B*5703 independently associated with slower HIV-1 disease progression in Rwandan women. AIDS 13: 1990–1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cox A. L., et al. 2005. Comprehensive analyses of CD8+ T cell responses during longitudinal study of acute human hepatitis C. Hepatology 42: 104–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Crawford H., et al. 2007. Compensatory mutation partially restores fitness and delays reversion of escape mutation within the immunodominant HLA-B*5703-restricted Gag epitope in chronic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 81: 8346–8351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dazert E., et al. 2009. Loss of viral fitness and cross-recognition by CD8+ T cells limit HCV escape from a protective HLA-B27-restricted human immune response. J. Clin. Invest. 119: 376–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Friebe P., Lohmann V., Krieger N., Bartenschlager R. 2001. Sequences in the 5′ nontranslated region of hepatitis C virus required for RNA replication. J. Virol. 75: 12047–12057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gaudieri S., et al. 2006. Evidence of viral adaptation to HLA class I-restricted immune pressure in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J. Virol. 80: 11094–11104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gaudieri S., et al. 2009. Hepatitis C virus drug resistance and immune-driven adaptations: relevance to new antiviral therapy. Hepatology 49: 1069–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goulder P. J., et al. 1996. Novel, cross-restricted, conserved, and immunodominant cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitopes in slow progressors in HIV type 1 infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 12: 1691–1698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goulder P. J. R., et al. 1997. Late escape from an immunodominant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response associated with progression to AIDS. Nat. Med. 3: 212–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Graham D. J., et al. 2006. A genotype 2b NS5B polymerase with novel substitutions supports replication of a chimeric HCV 1b:2b replicon containing a genotype 1b NS3-5A background. Antiviral Res. 69: 24–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Howe A. Y., et al. 2008. Molecular mechanism of hepatitis C virus replicon variants with reduced susceptibility to a benzofuran inhibitor, HCV-796. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52: 3327–3338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim A. Y., et al. 2011. Spontaneous control of HCV is associated with expression of HLA-B 57 and preservation of targeted epitopes. Gastroenterology 140: 686–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kuniholm M. H., et al. 2010. Specific human leukocyte antigen class I and II alleles associated with hepatitis C virus viremia. Hepatology 51: 1514–1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kuntzen T., et al. 2008. Naturally occurring dominant resistance mutations to hepatitis C virus protease and polymerase inhibitors in treatment-naive patients. Hepatology 48: 1769–1778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lechner F., et al. 2000. Analysis of successful immune responses in persons infected with hepatitis C virus. J. Exp. Med. 191: 1499–1512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Le Pogam S., et al. 2006. Selection and characterization of replicon variants dually resistant to thumb- and palm-binding nonnucleoside polymerase inhibitors of the hepatitis C virus. J. Virol. 80: 6146–6154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lin C., et al. 2005. In vitro studies of cross-resistance mutations against two hepatitis C virus serine protease inhibitors, VX-950 and BILN 2061. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 36784–36791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lohmann V., Hoffmann S., Herian U., Penin F., Bartenschlager R. 2003. Viral and cellular determinants of hepatitis C virus RNA replication in cell culture. J. Virol. 77: 3007–3019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lu L., Mo H., Pilot-Matias T. J., Molla A. 2007. Evolution of resistant M414T mutants among hepatitis C virus replicon cells treated with polymerase inhibitor A-782759. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51: 1889–1896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ludmerer S. W., et al. 2005. Replication fitness and NS5B drug sensitivity of diverse hepatitis C virus isolates characterized by using a transient replication assay. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49: 2059–2069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martinez-Picado J., et al. 2006. Fitness cost of escape mutations in p24 Gag in association with control of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 80: 3617–3623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McKiernan S. M., et al. 2004. Distinct MHC class I and II alleles are associated with hepatitis C viral clearance, originating from a single source. Hepatology 40: 108–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Migueles S. A., et al. 2003. The differential ability of HLA B*5701+ long-term nonprogressors and progressors to restrict human immunodeficiency virus replication is not caused by loss of recognition of autologous viral gag sequences. J. Virol. 77: 6889–6898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Migueles S. A., et al. 2000. HLA B*5701 is highly associated with restriction of virus replication in a subgroup of HIV-infected long term nonprogressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97: 2709–2714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Miura T., et al. 2009. HLA-B57/B*5801 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 elite controllers select for rare gag variants associated with reduced viral replication capacity and strong cytotoxic T-lymphocyte [corrected] recognition. J. Virol. 83: 2743–2755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Neumann-Haefelin C., et al. 2006. Dominant influence of an HLA-B27 restricted CD8+ T cell response in mediating HCV clearance and evolution. Hepatology 43: 563–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Neumann-Haefelin C., et al. 2010. Protective effect of human leukocyte antigen B27 in hepatitis C virus infection requires the presence of a genotype-specific immunodominant CD8+ T-cell epitope. Hepatology 51: 54–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36a. Neumann-Haefelin C., et al. HLA-B27 selects for rare escape mutations that significantly impair hepatitis C virus replication and require compensatory mutations. Hepatology, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Poon A. F., et al. 2007. Adaptation to human populations is revealed by within-host polymorphisms in HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus. PLoS Pathog. 3: e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rauch A., et al. 2009. Divergent adaptation of hepatitis C virus genotypes 1 and 3 to human leukocyte antigen-restricted immune pressure. Hepatology 50: 1017–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Salloum S., et al. 2008. Escape from HLA-B*08-restricted CD8 T cells by hepatitis C virus is associated with fitness costs. J. Virol. 82: 11803–11812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schneidewind A., et al. 2008. Structural and functional constraints limit options for cytotoxic T-lymphocyte escape in the immunodominant HLA-B27-restricted epitope in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid. J. Virol. 82: 5594–5605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schneidewind A., et al. 2007. Escape from the dominant HLA-B27-restricted cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response in Gag is associated with a dramatic reduction in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J. Virol. 81: 12382–12393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Soderholm J., et al. 2006. Relation between viral fitness and immune escape within the hepatitis C virus protease. Gut 55: 266–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tester I., et al. 2005. Immune evasion versus recovery after acute hepatitis C virus infection from a shared source. J. Exp. Med. 201: 1725–1731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thimme R., et al. 2002. Viral and immunological determinants of hepatitis C virus clearance, persistence, and disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99: 15661–15668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Thio C. L., et al. 2002. HLA-Cw*04 and hepatitis C virus persistence. J. Virol. 76: 4792–4797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Timm J., et al. 2004. CD8 epitope escape and reversion in acute HCV infection. J. Exp. Med. 200: 1593–1604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Timm J., et al. 2007. Human leukocyte antigen-associated sequence polymorphisms in hepatitis C virus reveal reproducible immune responses and constraints on viral evolution. Hepatology 46: 339–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tong X., et al. 2006. Identification and analysis of fitness of resistance mutations against the HCV protease inhibitor SCH 503034. Antiviral Res. 70: 28–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Troyer R. M., et al. 2009. Variable fitness impact of HIV-1 escape mutations to cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response. PLoS Pathog. 5: e1000365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Uebelhoer L., et al. 2008. Stable cytotoxic T cell escape mutation in hepatitis C virus is linked to maintenance of viral fitness. PLoS Pathog. 4: e1000143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ueno T., et al. 2008. CTL-mediated selective pressure influences dynamic evolution and pathogenic functions of HIV-1 Nef. J. Immunol. 180: 1107–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Welsch C., et al. 2008. Molecular basis of telaprevir resistance due to V36 and T54 mutations in the NS3-4A protease of the hepatitis C virus. Genome Biol. 9: R16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]