Abstract

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a fatal sequela associated with measles and is caused by persistent infection of the brain with measles virus (MV). The SI strain was isolated in 1976 from a patient with SSPE and shows neurovirulence in animals. Genome nucleotide sequence analyses showed that the SI strain genome possesses typical genome alterations for SSPE-derived strains, namely, accumulated amino acid substitutions in the M protein and cytoplasmic tail truncation of the F protein. Through the establishment of an efficient reverse genetics system, a recombinant SI strain expressing a green fluorescent protein (rSI-AcGFP) was generated. The infection of various cell types with rSI-AcGFP was evaluated by fluorescence microscopy. rSI-AcGFP exhibited limited syncytium-forming activity and spread poorly in cells. Analyses using a recombinant MV possessing a chimeric genome between those of the SI strain and a wild-type MV strain indicated that the membrane-associated protein genes (M, F, and H) were responsible for the altered growth phenotype of the SI strain. Functional analyses of viral glycoproteins showed that the F protein of the SI strain exhibited reduced fusion activity because of an E300G substitution and that the H protein of the SI strain used CD46 efficiently but used the original MV receptors on immune and epithelial cells poorly because of L482F, S546G, and F555L substitutions. The data obtained in the present study provide a new platform for analyses of SSPE-derived strains as well as a clear example of an SSPE-derived strain that exhibits altered receptor specificity and limited fusion activity.

INTRODUCTION

Measles is an acute highly contagious disease characterized by high fever and a maculopapular rash. Acute measles is accompanied by temporary and severe immunosuppression, and pneumonia caused by secondary bacterial infections is a major cause of measles-related death in children. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a fatal sequela associated with measles. It occurs at a mean latency period of 7 to 10 years after the acute measles stage of development (3, 52). SSPE is caused by persistent infection of the central nervous system (CNS) with measles virus (MV), and suffering from acute measles at an early age is a risk factor for developing SSPE (17). A recent analysis indicated that the risk of developing SSPE was 22 cases per 100,000 reported cases of acute measles (3).

The causative agent, MV, is an enveloped virus that belongs to the genus Morbillivirus in the family Paramyxoviridae. MV possesses a nonsegmented, negative-sense RNA genome that includes six linked tandem genes, N, P/V/C, M, F, H, and L. The genome is encapsidated by the nucleocapsid (N) protein and is associated with a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase composed of phosphoproteins (P proteins) and large proteins (L proteins) that form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex (12). Two types of glycoprotein spikes, the hemagglutinin (H) and fusion (F) proteins, are expressed on the viral envelope. The H protein is responsible for binding to cellular receptors on the target host cells. The signaling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM) expressed on immune system cells functions as the principal receptor for MV (62, 69). We and another group recently demonstrated that certain epithelial cells that form tight junctions express an unidentified receptor for MV that is designated the epithelial cell receptor (ECR) (25, 50, 59). Binding of the H protein to a receptor triggers F protein-mediated membrane fusion of the virus envelope and the host cell plasma membrane (12). These proteins are also expressed on the cell surface and cause cell-to-cell fusion. The matrix (M) protein plays crucial roles in the process of virus assembly via its interaction with both the RNP and the cytoplasmic tails of the glycoproteins. MV strains derived from patients with SSPE (SSPE strains) generally do not express a functional M protein, becoming defective in producing infectious virus particles, and thus spread via cell-to-cell fusion (10, 14–16, 18). In addition, SSPE strains usually have a deletion or an alteration in the cytoplasmic tail of the F protein (4, 9, 31, 44).

The SI strain was isolated in 1976 from a patient with SSPE by cultivating brain tissue biopsy samples with Vero cells (29). The patient was 8 years of age and had suffered from acute measles at 4 years of age (29). The SI strain was found to show neurovirulence, and all animals (mice, hamsters, and guinea pigs) inoculated intracerebrally with the SI strain showed neurological manifestations at 3 to 6 days after inoculation and eventually died (29). Despite these significant characteristics, molecular analyses of the SI strain have been poorly conducted. In the present study, we identified unique characteristics of the SI strain and identified substitutions responsible for the modulated receptor specificity and reduced membrane fusion activity. The present study also obtained data using a genetic engineering system of the SI strain expressing a fluorescent protein. This system could be a new platform for analyses of the molecular bases and pathogenesis of SSPE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

BHK/T7-9 cells constitutively expressing T7 RNA polymerase (20) were maintained in Dulbecco's minimum essential medium (DMEM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 7% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Vero/hSLAM (36) and CV1/hSLAM (58), which constitutively express human SLAM (hSLAM), were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 7% FBS and 0.5 mg/ml Geneticin (G418; Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). CHO cells and A549 cells constitutively expressing human SLAM, CHO/hSLAM (62), and A549/hSLAM (57), respectively, were maintained in RPMI medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 7% FBS and 0.5 mg/ml G418. Vero cells and IMR-32 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 7% FBS and 10% FBS, respectively. H358 (59) and II-18 (49) cells were maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS. SH-SY5Y cells were maintained in DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS (49, 59).

Plasmid constructions.

The first-strand cDNA of the SI strain antigenome was synthesized by reverse transcription of total RNA isolated from Vero/hSLAM cells infected with the SI strain. Eight DNA fragments covering the entire region of the SI strain genome were then generated by PCR. These fragments were cloned into pBluescriptII KS(+) vector (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) in a stepwise manner, generating a plasmid carrying the full-length antigenomic cDNA of the SI strain (detailed procedure provided upon request). A hammerhead ribozyme sequence (HHRz) was added between the T7 promoter sequence and the MV genome cDNA by a combination of PCR procedures using the synthesized DNA (5′-GTGAATTGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTGTTTGGTCTGATGAGGCCGAAAGGCCGAAACTCCGTAAGGAGTCACCAAACA AA-3′; the T7 promoter and HHRz sequences are shown in boldface and italics, respectively, and the MV genome cDNA sequence is underlined). To generate an additional transcriptional unit for a green fluorescent protein (GFP) derived from Aequorea coerulescens (AcGFP; Clontech, Palo Alto, CA), a fragment containing the open reading frame (ORF) of AcGFP was amplified by PCR using primer pair 5′-GGCGCGCCATGGTGAGCAAG-3′ and 5′-GACGTCTTACTTGTACAGCTCGT-3′ (sequences corresponding to the AscI and AatII sites are shown in italics; sequences corresponding to the initiation and termination codons are shown in boldface). The fragment was combined with the synthesized cDNA fragments containing the region between the H and L protein open reading frames of the IC-B strain by a combination of PCR procedures. The nucleotide sequences of the synthesized cDNA fragments were 5′-ACTAGTGAAATAGACATCAGAATTAAGAAAAACGTAGGGTCCAAGTGGTTTCCCGTTGGCGCGCC-3′ and 5′-GACGTCTGCCAGTGAACCGATCACATGATGTCACCCAGACATCAGGCATACCCACTAGT-3′ (sequences corresponding to SpeI sites are shown in boldface, sequences corresponding to AscI and AatII sites are shown in italics, and sequences corresponding to the gene end [GE] of the H gene and gene start [GS] of the L gene are underlined). The fragment containing the transcriptional unit for AcGFP was then inserted into the SpeI site between the H and L genes. The generated construct was named pHHRz-SI-AcGFP. Using a similar procedure, the additional transcriptional unit for AcGFP was also inserted into the p(+)MV323 plasmid, which carries the full-length antigenomic cDNA of the IC-B strain (60). The resulting plasmid was named p(+)MV323-AcGFP. A SalI-AatII fragment containing a region of the M, F, and H genes of p(+)MV323-AcGFP was replaced with a corresponding fragment of pHHRz-SI-AcGFP, and the generated construct was named p(+)MV323/SI-MFH-AcGFP. A SalI-BstEII fragment containing a region of the M gene of the pHHRz-SI-AcGFP was replaced with a corresponding fragment of p(+)MV323, and the generated construct was named pHHRz-SI/ICM-AcGFP. To generate support plasmids for the rescue of recombinant MVs from cloned cDNAs, DNA fragments encoding the N, P, and L proteins of the wild-type (wt) MV strains (IC-B or 9301B) were cloned into the pCITE vector (Novagen, Madison, WI), generating pCITE-IC-N, pCITE-IC-PΔC, and pCITEko-9301B-L, respectively. DNA fragments encoding the M proteins of the IC-B and SI strains fused with a red fluorescent protein, mCherry (Clontech), at the carboxyl-terminal end were generated by a combination of PCR procedures and inserted into a mammalian expression vector, pCA7 (32, 57). The resulting plasmids were named pCA7-FR-IC-M-mCherry and pCA7-FR-SI-mCherry, respectively. DNA fragments encoding the F proteins of the IC-B and SI strains were also amplified by PCR and cloned into pCAGGS (32), generating pCAGGS-IC-F and pCAGGS-SI-F, respectively. Similarly, DNA fragments encoding the H proteins of the IC-B and SI strains were amplified and cloned into pCAGGS, generating pCAGGS-IC-H and pCAGGS-SI-H, respectively. By replacing the SalI-XhoI, EcoRI-SalI, KpnI-XhoI, and SalI-KpnI regions of pCAGGS-IC-F with the corresponding region of pCAGGS-SI-F, four plasmids encoding chimeric F proteins between the IC-B and SI strains, designated pCAGGS-IC/SI-F-1, -F-2, -F-3, and -F-4, respectively, were generated. An amino acid substitution, G300E, was introduced into pCAGGS-SI-F, and five other amino acid substitutions, N390M, L482F, S546G, F555L, and I564L, were introduced independently into pCAGGS-IC-H by site-directed mutagenesis using complementary primer pairs.

Antibodies.

A mouse monoclonal antibody (MAb) against CD46 (M75) was kindly provided by T. Seya (46). Mouse MAbs against the proteins encoded by MV H (B5), F (C527), and M (A23, A24, A27, A154, A157, A177, B46, A39, A41, A42, A51, and A133) were kindly provided by T. A. Sato (42).

Viruses.

BHK/T7-9 cells were transfected with full-length genome plasmids carrying the antigenomes of MV and three support plasmids, pCITE-IC-N, pCITE-IC-PΔC, and pCITEko-9301B-L, by the use of Lipofectamine LTX Plus reagent (Invitrogen). After 2 days, the transfected cells were cocultured with Vero/hSLAM cells. IC323-AcGFP, SI-AcGFP, IC/SI-MFH-AcGFP, and SI/ICM-AcGFP were generated from p(+)MV323-AcGFP, pHHRz-SI-AcGFP, p(+)MV323/SI-MFH-AcGFP, and pHHRz-SI/ICM-AcGFP, respectively. The generated MVs were propagated in Vero/hSLAM cells. Infectious virus-like particles of SI-AcGFP and IC/SI-MFH-AcGFP were prepared by incubating the cells with 5 μg/ml cytochalasin D (Sigma) at 35°C for 30 min, as described previously (19). The infectious virus-like particles were concentrated using PEG-it precipitation solution (System Biosciences Inc., Mountain View, CA). The cell infectious units (CIUs) of the recombinant MVs expressing a fluorescent protein were determined using Vero/hSLAM cells, as described previously (51). To analyze the cytopathic effects (CPEs), monolayers of cells in 6-well cluster plates were infected with 500 CIUs of MV and the cells were observed daily using an Axio Observer.D1 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Virus growth.

Monolayers of Vero/hSLAM cells in 24-well plates were infected with recombinant MVs at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 per cell. At various time intervals, cell-free virus was obtained from the culture supernatants, and cell-associated virus was recovered from infected cells in 0.5 ml of DMEM-supplemented 7% FBS by freezing and thawing.

Virus titration.

Monolayers of Vero/hSLAM cells in 6-well cluster plates were infected with serially diluted virus samples, incubated for 1 h at 37°C, and overlaid with DMEM containing 7% FBS and 1% agarose. PFU numbers were determined by counting the number of plaques.

Phylogenic tree analysis and Ka/Ks calculation.

Nucleotide and amino acid sequence alignments and a phylogenic distance analysis were performed with the ClustalW program (63) at the genomeNet website maintained by the Kyoto University Bioinformatics Center. A phylogenic tree constructed using SI, IC-B, 9301B, WA.USA/17.98, and reference strains (66) was drawn using FigTree software. Ka/Ks calculations were performed using KaKs Calculator version 2.0 software (64). Briefly, using the two nucleotide sequences of each protein-coding region, the nonsynonymous and synonymous substitution rates (Ka and Ks, respectively) were calculated by counting the numbers of nonsynonymous and synonymous sites (NA and NS, respectively) and the numbers of nonsynonymous and synonymous substitutions (MA and MS, respectively). MA/NA and MS/NS represent the Ka and Ks substitution rates, respectively.

Immunofluorescence staining.

Monolayers of Vero/hSLAM cells were seeded in 24-well plates or on coverslips in six-well cluster plates. Some monolayers were transfected with expression plasmids encoding M protein tagged with mCherry or not tagged. Other monolayers were infected with recombinant MVs and incubated with 50 μg/ml of a fusion-blocking peptide, Z-D-Phe-Phe-Gly (Peptide Institute Inc., Osaka, Japan), as described previously (41). At 24 h posttransfection or at 2 or 5 days postinoculation (p.i.) (using IC323-AcGFP or SI-AcGFP, respectively), the cells were fixed and permeabilized with phosphate-buffered saline containing 2.5% formaldehyde and 0.5% Triton X-100. The cells were then stained with a mouse MAb against the M protein for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with an Alexa Fluor 488- or 594-conjugated secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 1 h at room temperature. The nuclei of the infected cells were stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) at 0.2 μg/ml. The cells were observed using a FluoView FV1000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell-to-cell fusion assay.

CHO/hSLAM, CV1/hSLAM, Vero, H358, or II-18 cells were seeded in 24-well plates, transfected with the H protein-expressing plasmid (0.5 μg) together with the F protein-expressing plasmid (0.5 μg), and incubated in the presence or absence of an anti-CD46 antibody (M75). At 1, 2, or 3 days posttransfection, the cells were fixed with methanol and stained with Giemsa solution (Sigma). The stained cells were observed under an Axio Observer.D1 microscope. To quantify cell-to-cell fusion, monolayers of cells were transfected with H protein-expressing plasmid (0.3 μg) and F protein-expressing plasmid (0.3 μg) together with a red fluorescent protein (mCherry)-expressing plasmid (0.3 μg). At 48 h posttransfection, areas expressing mCherry autofluorescence were measured using an Axio Observer.D1 microscope and ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/index.html). Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel version 14.1.2 software.

Flow cytometry.

CHO/hSLAM cells were transfected with the H or F protein-expressing plasmid (0.5 μg). At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were incubated with mouse MAbs B5 and C527 specific for the H and F proteins, respectively, followed by incubation with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Molecular Probes). The cells were analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Minigenome assay.

BHK/T7-9 cells were transfected with 0.2 μg of p18MGFLuc01 minigenome plasmid (23) together with 0.2 μg of pCITE-IC-N and various amounts of pCITE-IC-PΔC and pCITEko-9301B-L. At 48 h posttransfection, the enzymatic activity of firefly luciferase was measured using a Dual Glo luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI) and a Mithras LB 940 luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the SI strain is available under GenBank accession number JF791787.

RESULTS

Characterization of the genome of the SI strain.

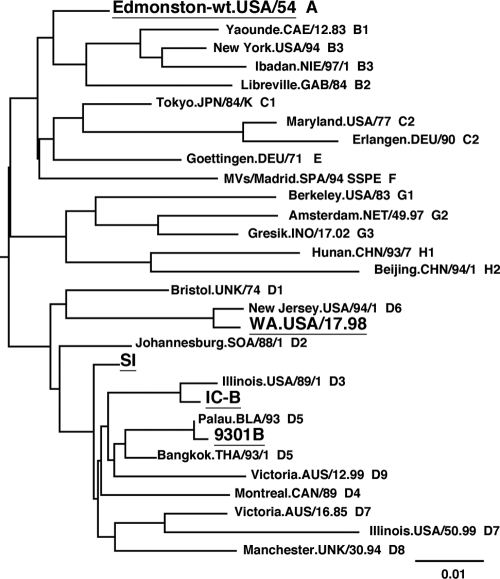

We determined the entire genome nucleotide sequence of the SI strain. A phylogenic tree drawn on the basis of the 450-nucleotide sequence that encodes the carboxyl-terminal 150 amino acids of the N protein showed that the SI strain was classified into clade D but did not belong to a specific genotype (Fig. 1). Genotype analyses performed using a program at a website for measles nucleotide surveillance (MeaNS) (http://www.hpa-bioinformatics.org.uk/Measles/Public/Web_Front/main.php) confirmed the data for the phylogenic tree analysis (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The entire genome nucleotide sequence of the SI strain was compared with those of three other strains in clade D, strain IC-B (genotype D3; GenBank accession number NC_001498), strain 9301B (genotype D5; GenBank accession number AB012948), and strain WA.USA/17.98 (genotype D6; GenBank accession number DQ227321) (2, 54, 61). The nucleotide sequences of the regulatory regions (i.e., the gene start, gene end, and integenic sequences) (38) were highly conserved in the SI strain genome. As indicated in previous reports (9, 11, 68), highly biased uracil-to-cystine substitutions were observed in the M gene (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). As also observed for other SSPE strains, nonsynonymous substitutions were accumulated in the M protein reading frame of the SI strain (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The data for the comparison between the SI and IC-B strains are shown in the present paper, but similar results were obtained in the comparisons between the SI and other clade D MV strains. The Ka/Ks ratios were analyzed to reveal differences between the SI and clade D MV strains (IC/SI, 9301/SI, and WA98/SI) and between the Edmonston wild-type (wt) strain (genotype A; GenBank accession number AF266288) and clade D MV strains (IC/Edwt, 9301/Edwt, and WA98/Edwt) (37) (the phylogenic tree in Fig. 1 shows the relationships among the SI, IC-B, 9301B, WA.USA/17.98, and Edmonston wt strains). The data of comparisons between the Edmonston wt and clade D MV strains mostly reflect the selection pressure that operated during the natural evolution of wt MVs, while the data showing comparisons between the SI and clade D MV strains reflect the selection pressure that operated during persistent infection in the brain in addition to the natural evolution of MV. Previously, a similar study was performed by Woelk et al. (67). For the M protein reading frame, the Ka/Ks ratios in the comparisons between the Edmonston wt and clade D MV strains were ∼0.03, whereas the ratios in the comparisons between the SI and clade D MV strains were 11 to 12 times greater than those observed in comparisons between the Edmonston wt and clade D MV strains (Table 1), confirming that a dynamic selection or a reduced stabilizing selection pressure operated for the M protein of the SI strain, as observed for other SSPE strains (67). Similarly, although the amino acid sequence of the F protein was highly conserved during the natural evolution of MV (Ka/Ks = 0.0000 ∼ 0.0359), this was not the case during persistent infection in the brain (Ka/Ks = 0.1825 ∼ 0.2504) (Table 1). Compared with those of IC-B, 12 amino acid changes were found in the F protein of the SI strain, including a nonsense mutation at amino acid position 532 (Table 2). These changes in the F protein are typical of SSPE strains (4, 9, 31, 44). For the N, H, and L protein reading frames, in contrast, the Ka/Ks ratios revealed by the comparisons between the SI and clade D MV strains were similar to those observed between the Edmonston wt and clade D MV strains (Table 1). These data indicated that similar levels of stabilizing selection pressure operated for the N, H, and L protein reading frames of the SI strain during the persistent infection in the brain. For the P gene, it was not simple to assess the data for the Ka and Ks values, since the gene contains overlapping reading frames. Nonetheless, it was evident that both the C and V nonstructural proteins were highly conserved during the persistent infection in the brain. For the C protein-reading frame, the Ka values for the IC/SI and WA93/SI comparisons were as much as 3 to 5 times lower than those for the IC/Edwt and WA93/SI comparisons (Table 1). Indeed, no amino acid substitution was found in the C protein of the SI strain compared with that of the 9301B strain. Similarly, no amino acid substitution was found in the V protein-unique region of the SI strain compared with that of the WA.USA/17.98. strain. The V protein-unique region of the 9301B strain also had the same amino acid sequence as those of the SI and WA.USA/17/98 strains except that the 9301B V protein possessed an additional single amino acid at the carboxyl-terminal end, because it terminated one codon later (since this additional codon was not included in calculation, the Ka of 9301/SI comparison was zero [Table 1]). These data suggested that both the C and V proteins played important roles in the survival of the SI strain in the brain.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenic tree drawn on the basis of the 450-nucleotide sequence that encodes the carboxyl-terminal 150 amino acids of the N protein. The names of the strains used for sequence comparisons in this study (Edmonston-wt, SI, IC-B, 9301B, and WA.USA/17.98) are underlined.

Table 1.

Ks, Ka, and Ka/Ks values from comparisons of Edmonston wild-type, IC-B, 9301B, WA.USA/17.98, and SI strainsa

| Protein reading frame | Gene region(s) | Nucleotidesb |

Ks |

Ka |

Ka/Ks |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC(D3)/Edwt, 9301(D5)/Edwt, WA98(D6)/Edwt | IC(D3)/SI, 9301(D5)/SI, WA98(D6)/SI | IC(D3)/Edwt, 9301(D5)/Edwt, WA98(D6)/Edwt | IC(D3)/SI, 9301(D5)/SI, WA98(D6)/SI | IC(D3)/Edwt, 9301(D5)/Edwt, WA98(D6)/Edwt | IC(D3)/SI, 9301(D5)/SI, WA98(D6)/SI | |||

| N | 1-1578 | 0.0790, 0.0960, 0.1033 | 0.0512, 0.0703, 0.1218 | 0.0117, 0.0113, 0.0092 | 0.0046, 0.0050, 0.0075 | 0.1486, 0.1178, 0.0892 | 0.0898, 0.0712, 0.0618 | |

| P | P | 1-1524 | 0.0416, 0.0443, 0.0330 | 0.0246, 0.0273, 0.0330 | 0.0114, 0.0176, 0.0132 | 0.0079, 0.0141, 0.0096 | 0.2740, 0.3981, 0.3982 | 0.3195, 0.5150, 0.2918 |

| P/C | 22-582 | 0.0222, 0.0223, 0.0297 | 0.0073, 0.0074, 0.0147 | 0.0191, 0.0239, 0.0215 | 0.0024, 0.0071, 0.0047 | 0.8596, 1.0739, 0.7241 | 0.3217, 0.9645, 0.3212 | |

| P/V | 691-903 | 0.0178, 0.0177, 0 | 0.0177, 0.0176, 0 | 0, 0.0064, 0.0129 | 0.0195, 0.0262, 0.0327 | 0, 0.3643, NAc | 1.0991, 1.4842, NA | |

| P′ | 1–21 + 583–690 + 904–1524 | 0.0648, 0.0704, 0.0465 | 0.0405, 0.0461, 0.0585 | 0.0088, 0.0160, 0.0071 | 0.0088, 0.0160, 0.0071 | 0.1361, 0.2272, 0.1516 | 0.2179, 0.3472, 0.1206 | |

| C | 1–561 | 0.0464, 0.0705, 0.0543 | 0.0075, 0.0305, 0.0151 | 0.0119, 0.0095, 0.0143 | 0.0024, 0, 0.0047 | 0.2561, 0.1345, 0.2629 | 0.3132, 0, 0.3127 | |

| V | V transd | 690–902 | 0, 0.0217, 0.0439 | 0.0434, 0.0667, 0.0902 | 0.0063, 0, 0 | 0.0063, 0, 0 | NA, 0, 0 | 0.1449, 0, 0 |

| M | 1–1008 | 0.0842, 0.0936, 0.0892 | 0.2135, 0.2134, 0.2141 | 0.0026, 0.0026, 0.0026 | 0.0758, 0.0758, 0.0772 | 0.0310, 0.0279, 0.0293 | 0.3551, 0.3552, 0.3606 | |

| F | 1–1653 | 0.0566, 0.0627, 0.0675 | 0.0355, 0.0459, 0.0621 | 0, 0.0024, 0.0024 | 0.0089, 0.0113, 0.0113 | 0, 0.0359, 0.0357 | 0.2504, 0.2470, 0.1825 | |

| H | 1–1854 | 0.0902, 0.0877, 0.0724 | 0.0675, 0.0651, 0.0907 | 0.0114, 0.0100, 0.0092 | 0.0085, 0.0071, 0.0135 | 0.1263, 0.1135, 0.1276 | 0.1262, 0.1089, 0.1490 | |

| L | 1–6549 | 0.0801, 0.0927, 0.0822 | 0.0601, 0.0687, 0.0781 | 0.0047, 0.0051, 0.0049 | 0.0050, 0.0054, 0.0058 | 0.0584, 0.0548, 0.0594 | 0.0828, 0.0782, 0.0739 | |

Edwt, Edmonston wild type; IC(D3), IC-B; 9301(D5), 9301B; WA98(D6), WA.USA/17.98.

The first nucleotide of the initiation codon for each open reading frame is taken as 1.

NA, not applicable.

V trans is the C-terminal region unique to the V protein.

Table 2.

Amino acid substitutions in the F proteins among the IC, SI, and Edmonston strains

| Amino acid no. | Amino acid substitution(s) or category |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| IC | SI | Ed | |

| 78 | R | G | R |

| 165 | R | K | R |

| 167 | A | T | A |

| 187 | I | V | I |

| 242 | I | T | I |

| 246 | L | F | L |

| 247 | E | K | E |

| 268 | G | D | G |

| 300 | E | G | E |

| 487 | M | I | M |

| 532 | R | Stop | R |

| 533–550 | 18 aaa | Deletion | 18 aa |

aa, amino acids.

Generation of a recombinant SI strain expressing a fluorescent protein by establishment of an efficient MV rescue system.

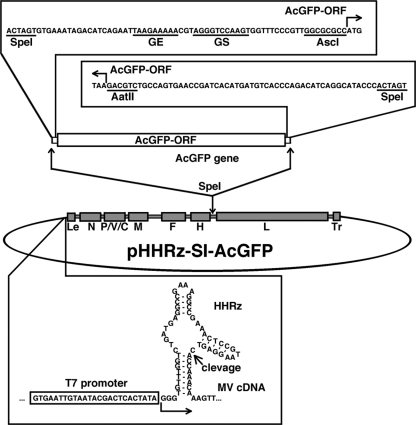

The SI strain did not produce cell-free infectious particles and spread poorly in cell cultures (data not shown). In addition, a CPE was barely detectable in some cultured cells, although the SI strain replicated in them (data not shown). Many studies have shown that the use of recombinant viruses genetically engineered to express a fluorescent protein is greatly advantageous for monitoring virus infections, especially when the virus infection shows a small or weak CPE. Therefore, we decided to generate a recombinant SI strain expressing a fluorescent protein. A full-length genome cDNA of the SI strain possessing an additional transcriptional unit encoding AcGFP between the H and L genes was generated and inserted into the pBluescript vector downstream of the T7 promoter (Fig. 2). The T7 promoter was followed by three guanines that enhance the transcription efficiency (Fig. 2). Since these guanines produce extra guanine residues at the 5′ end of the synthesized MV antigenome, a precise 5′ end for the MV antigenome was created by inserting HHRz between the three guanines and the first viral nucleotide (Fig. 2). The resulting full-length genome plasmid was designated pHHRz-SI-AcGFP. BHK/T7-9 cells, which represent a baby hamster kidney (BHK) cell-derived clone constitutively expressing T7 RNA polymerase (20) (kindly provided by M. Sugiyama and N. Ito), has been shown to be highly potent for initiating the replication cycles of other negative-strand RNA viruses from cloned cDNAs (20, 48). By the use of previously reported methods of studies employing BHK/T7-9 cells (48), the cDNAs of the N, P, and L genes of MV were inserted into the pCITE vector; the resulting plasmids were termed pCITE-IC-N, pCITE-IC-PΔC, and pCITEko-9301B-L, respectively. These plasmids were designed to create an internal ribosome entry site at the 5′ terminus of the N, P, and L mRNAs. Since the ratios of the plasmids expressing the N, P, and L proteins were previously reported to be critical for the initiation of infectious cycles of paramyxoviruses from cloned cDNAs (13, 21, 26), the optimal ratio for these plasmids was determined using a minireplicon assay for MV (23). The analyses indicated that 0.20, 0.15, and 0.40 μg of pCITE-IC-N, pCITE-IC-PΔC, and pCITEko-9301B-L, respectively, were optimal for the expression of the MV minireplicon gene (luciferase) in BHK/T7-9 cells cultured in a 24-well cluster plate (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). When BHK/T7-9 cells cultured in a 6-well cluster plate were transfected with 5.0 μg of pHHRz-SI-AcGFP together with three support plasmids (0.80, 0.60, and 1.60 μg of pCITE-IC-N, pCITE-IC-PΔC, and pCITEko-9301B-L, respectively), infectious cycles of rSI-AcGFP were efficiently initiated from pHHRz-SI-AcGFP. Subsequently, the recombinant SI strain expressing AcGFP (rSI-AcGFP) was maintained in Vero/hSLAM cells cocultured with BHK/T7-9 cells.

Fig. 2.

Diagram of the genome plasmid with insertion of an additional transcriptional unit and the HHRz sequence. Transcriptional regulatory regions (gene end [GE], intergenic, and gene start [GS] sequences) and the coding sequence for AcGFP (AcGFP-ORF) were inserted at the junction between the H and L genes by the use of appropriate restriction enzyme recognition sites (SpeI, AscI, and AatII). The recombinant genome also possesses an HHRz upstream the authentic virus genome.

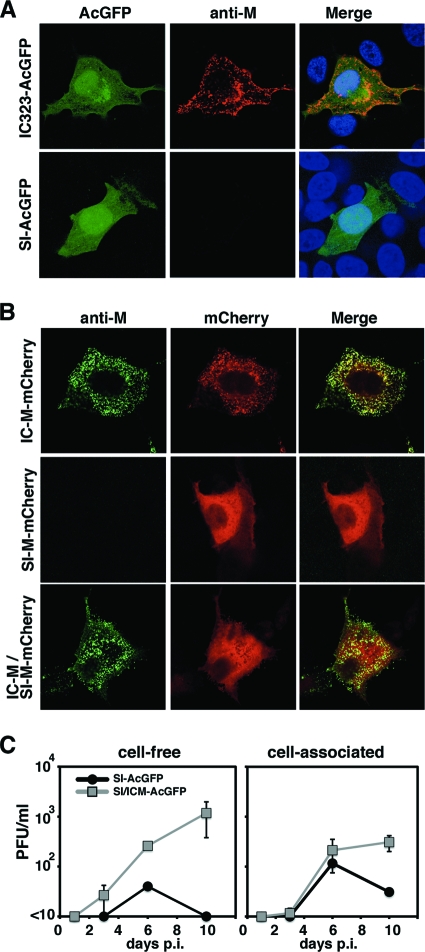

Properties of the M protein of the SI strain.

Using various MAbs against the M protein (42), an indirect immunofluorescence assay was performed. A total of 12 MAbs that have been shown to recognize antigenic sites II, III, and IV of the M protein were used (42) (Table 3). A recombinant IC323 strain expressing AcGFP (IC323-AcGFP) was generated and used as a control. The IC323 strain is a recombinant MV based on the wt IC-B strain (60). In cells infected with IC323-AcGFP, all the MAbs detected the M protein (Fig. 3A and Table 3). However, in cells infected with the SI or rSI-AcGFP strains, all the MAbs failed to detect the M protein (Fig. 3A and Table 3 and data not shown). These data suggested a lack of M protein expression in cells infected with the SI and rSI-AcGFP strains. Sato et al. (43) also previously showed that M protein expression was missing in cells infected with the SI strain. The M proteins of the SI and IC-B strains were expressed in cells by the use of expression plasmids. The carboxyl termini of the M proteins were tagged with mCherry red fluorescent protein. All the MAbs detected the IC-B strain-derived M protein despite the mCherry tag (Table 3). In contrast, none of the MAbs detected the SI strain-derived M protein, although bright mCherry fluorescence was detected in these cells (Fig. 3B and Table 3). These data indicated that the antigenicity of the M protein of the SI strain was totally different from that of the M protein of the IC-B strain and that none of the MAbs recognizing antigenic sites II, III, and IV reacted with the M protein of the SI strain. Therefore, we could not reach a conclusion as to whether the M protein was expressed in cells infected with the SI strain. However, analyses using the expression plasmids demonstrated that, unlike the M protein of the IC-B strain, the M protein of the SI strain was distributed homogeneously in cells (Fig. 3B). The M protein of the IC-B strain was distributed beneath the plasma membrane and formed small dots in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3B). To elucidate the functional difference between the IC-B and SI strains with respect to the M gene, we generated a recombinant MV with a modified SI strain genome in which the M gene was replaced with the M gene of the IC-B strain. The resulting recombinant MV was designated SI/ICM-AcGFP. A growth kinetics analysis showed that, unlike SI-AcGFP, SI/ICM-AcGFP produced cell-free virus well and the cell-free virus titer of SI/ICM-AcGFP was ∼1,000 times higher than that of the SI-AcGFP at 10 days p.i. (Fig. 3C). The result demonstrated that SI-M protein was less involved in the budding stage. With these data, we concluded that the SI strain does not express a functional M protein.

Table 3.

Detection of the M protein by an indirect immunofluorescence assay

| MAb clone no. | Antigenic site | Assay result |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC323-AcGFP | SI-AcGFP | IC-M-mCherry | SI-M-mCherry | ||

| A23 | II | + | − | + | − |

| A24 | II | + | − | + | − |

| A27 | II | + | − | + | − |

| A154 | II | + | − | + | − |

| A157 | II | + | − | + | − |

| A177 | II | + | − | + | − |

| B46 | II | + | − | + | − |

| A39 | III | + | − | + | − |

| A41 | III | + | − | + | − |

| A42 | III | + | − | + | − |

| A51 | III | + | − | + | − |

| A133 | IV | + | − | + | − |

Fig. 3.

Distribution of the M protein and effect on viral growth of strain SI possessing the IC-M gene. (A) Distribution of the M protein in cells infected with recombinant MV. Vero/hSLAM cells were infected with IC323-AcGFP or SI-AcGFP. At 2 (IC323-AcGFP) or 5 (SI-AcGFP) days postinfection, the cells were stained with an anti-M protein MAb (A42) and an Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (B) Distribution of the mCherry-fused M protein. Vero/hSLAM cells were transfected with the M protein-expressing plasmids IC-M–mCherry, SI-M–mCherry, and IC-M plus SI-M–mCherry. At 1 day posttransfection, the cells were stained with an anti-M protein MAb (A42) and an Alexa 488-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody. The cells were observed under a confocal microscope. (C) Replication kinetics of recombinant MVs. Vero/hSLAM cells were infected with recombinant MVs at an MOI of 0.01, and infectious titers in culture medium (cell-free) and cells (cell-associated) were determined at 1, 3, 6, and 10 days p.i. Data represent the means ± standard deviations (SD) of results from triplicate samples.

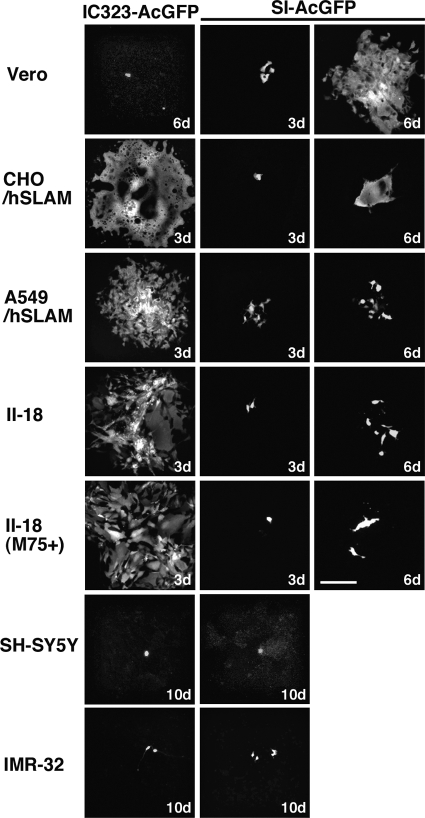

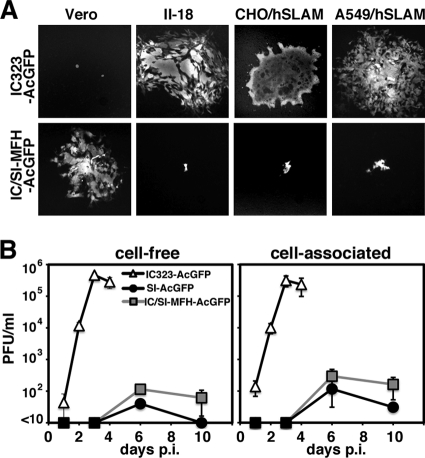

The SI strain exhibits limited syncytium-forming activity.

Various types of cells were infected with SI-AcGFP and IC323-AcGFP. IC323-AcGFP poorly entered Vero cells (SLAM−/CD46+) and did not produce a syncytium (Fig. 4). On the other hand, SI-AcGFP was able to produce syncytia in Vero cells (Fig. 4). Table 4 shows the amino acid substitutions in the H protein. Among them, the S546G substitution is the one that probably contributed to the ability of SI-AcGFP to produce syncytia in Vero cells, because this mutation allows MV to use CD46 as a receptor (69). On the other hand, SI-AcGFP failed to produce syncytia in II-18 cells (ECR+, CD46+), although IC323-AcGFP replicated and produced syncytia in these cells efficiently (Fig. 4). An MAb against CD46 (M75) had a neutral effect on the SI-AcGFP infection of II-18 cells. Similar results were obtained for the infection of SLAM-positive cells (CHO/hSLAM, A549/hSLAM). SI-AcGFP produced syncytia poorly in these cells, whereas IC323-AcGFP produced syncytia very efficiently. These data demonstrate that the SI strain has limited activity in inducing syncytia in SLAM- or ECR-expressing cells, although it has acquired the ability to use CD46 as an alternative receptor. Although three neural cell lines (SK-N-SH, IMR-32, and SH-SY5Y) were infected with SI-AcGFP and IC323-AcGFP, no syncytia were observed in these cells (Fig. 4 and data not shown).

Fig. 4.

AcGFP autofluorescence in cells infected with IC323-AcGFP and SI-AcGFP. Vero, CHO/hSLAM, A549/hSLAM, II-18, SH-SY5Y, and IMR-32 cells were infected with IC323-AcGFP or SI-AcGFP. Some II-18 cells were incubated with an anti-CD46 MAb (M75). The cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope at the indicated days (d). Bar, 0.20 mm.

Table 4.

Amino acid substitutions in the H proteins of the IC, SI, and Edmonston strains

| Amino acid no. | Amino acid substitution |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| IC | SIa | Edb | |

| 7 | R | Q* | R |

| 71 | H | R* | H |

| 174 | A | A | T |

| 176 | A | A | T |

| 211 | S | S | G |

| 235 | G | E | E |

| 243 | G | G | R |

| 252 | H | H | Y |

| 276 | F | F | L |

| 284 | F | F | L |

| 296 | F | F | L |

| 302 | R | R | G |

| 334 | R | Q | Q |

| 390 | N | M* | I |

| 416 | N | N | D |

| 446 | T | S | S |

| 481 | N | N | Y |

| 482 | L | F* | L |

| 484 | T | T | N |

| 546 | S | G* | S |

| 555 | F | L* | F |

| 564 | I | L* | I |

| 575 | K | Q | Q |

| 600 | V | V | E |

Asterisks indicate amino acids unique to the SI strain.

Edmonston strain; GenBank accession number K01711.

The membrane-associated protein genes (M, F, and H) determine the growth phenotype of the SI strain.

The amino acid sequences of the RNP component proteins (N, P, and L proteins) and nonstructural C and V proteins were well conserved in the SI strain (Table 1). We generated a recombinant MV possessing the IC323 genome in which the M, F, and H genes were replaced with those of the SI strain. The recombinant MV was designated IC/SI-MFH-AcGFP. The various types of cells shown in Fig. 4 were infected with IC/SI-MFH-AcGFP. IC/SI-MFH-AcGFP replicated poorly in SLAM- and ECR-positive cells and did not produce syncytia in these cells (Fig. 5A). A growth kinetics analysis of Vero/hSLAM cells, which were susceptible to all recombinant MVs, showed that IC/SI-MFH-AcGFP hardly produced cell-free viruses and exhibited a growth phenotype similar to that of SI-AcGFP (Fig. 4 and 5B). These data indicated that the membrane-associated protein-encoding genes (i.e., the M, F, and H genes) were responsible for the growth phenotype of the SI strain.

Fig. 5.

Effect on viral growth of strain IC possessing the SI-MFH gene in various cell lines. (A) AcGFP fluorescence in cells infected with recombinant MVs. Vero, II-18, CHO/hSLAM, and A549/hSLAM cells were infected with IC323-AcGFP or IC323/SI-MFH-AcGFP. The cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope at 3 (II-18, CHO/hSLAM, and A549/hSLAM) and 6 (Vero) days postinfection. (B) Replication kinetics of recombinant MVs. Vero/hSLAM cells were infected with recombinant MVs at an MOI of 0.01. At various time intervals, infectious titers in culture medium (cell-free) and cells (cell-associated) were determined. Data represent the means ± standard deviations (SD) of the results of experiments performed with triplicate samples.

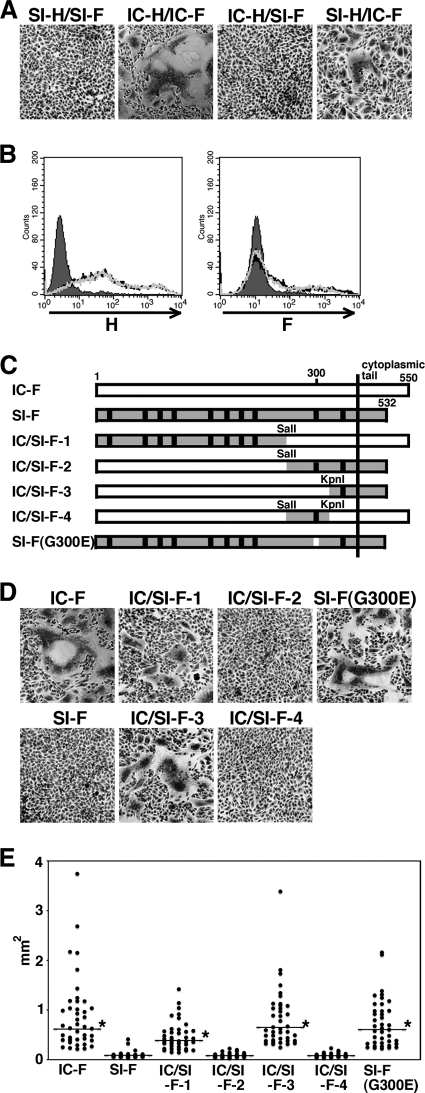

The E300G substitution in the F protein is responsible for the reduced membrane fusion activity.

Previous papers have indicated that the typical changes in SSPE strains, namely, the lack of M protein expression and cytoplasmic tail truncation of the F protein, enhance the syncytium-forming activity of MV (6, 7). Indeed, other previous papers have shown high fusogenic activities of SSPE strains (1, 4, 8). Despite exhibiting the changes typical in SSPE strains, SI-AcGFP and IC/SI-MFH-AcGFP showed limited syncytium-forming activities (Fig. 4 and 5B). Using expression plasmids, the syncytium-forming activities of the H and F proteins of the SI strain were analyzed in CHO/hSLAM cells (SLAM+). When the F protein of the SI strain (SI-F) was expressed together with the H protein of the SI strain (SI-H), no syncytia were detected (Fig. 6A; SI-H/SI-F). In contrast, many syncytia were observed when the F and H proteins of the IC-B strain (IC-F and IC-H, respectively) were expressed (Fig. 6A; IC-H/IC-F). Flow cytometry analyses indicated that the expression levels of SI-F and SI-H, respectively, were similar to those of IC-F and IC-H (Fig. 6B). The combination of SI-F and IC-H also showed poor syncytium-forming activity (Fig. 6A; IC-H/SI-F). On the other hand, when IC-F was coexpressed with SI-H, many syncytia, albeit smaller in size than the syncytia induced by IC-F and IC-H, were detected (Fig. 6A; SI-H/IC-F). These data indicated that both the SI-F and SI-H proteins exhibited lower activities than the IC-F and IC-H proteins in inducing syncytia in CHO/hSLAM cells. To identify the mutation(s) that impaired the syncytium-forming activity of SI-F, four chimeric F proteins (IC/SI-F-1, -F-2, -F-3, and -F-4) were generated using the SI and IC-B strains (Fig. 6C). These chimeric F proteins were coexpressed with IC-H. Two chimeric F proteins, IC/SI-F-2 and IC/SI-F-4, failed to produce syncytia (Fig. 6D and E). These data showed that a region between the SalI and KpnI recognition sites (amino acid positions 271 and 324) in SI-F severely restricted its membrane fusion activity (Fig. 6C). In this region, only a single amino acid substitution, E300G, was found in comparisons of SI-F and IC-F (Fig. 6C and Table 2). A glycine residue at amino acid position 300 in SI-F was replaced with a glutamic acid. The mutant F protein [Fig. 6C; SI-F(G300E)] was expressed with IC-H. The data indicated that SI-F(G300E) caused membrane fusion as well as IC-F did (P < 0.01) [Fig. 6D and E; SI-F(G300E)]. These findings indicated that the SI-F protein exhibited a restricted membrane fusion activity that was mainly caused by the E300G substitution.

Fig. 6.

Syncytium formation in cells expressing H and F proteins and identification of the amino acid residue in the F protein of the SI strain critical for reducing cell-to-cell fusion. (A) Syncytium formation in cells expressing H and F proteins of the IC-B or SI strains. CHO/hSLAM cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing the H protein of the IC-B or SI strain (IC-H or SI-H, respectively) together with a plasmid expressing the F protein of the IC-B or SI strain (IC-F or SI-F, respectively). At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were observed under a microscope after Giemsa staining. (B) Expression of the MV envelope proteins on the cells. CHO/hSLAM cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing IC-H, SI-H, IC-F, or SI-F. The cells expressing IC-H (black line) and SI-H (gray line) were stained with an anti-H protein MAb (left panel), and the cells expressing IC-F (black line) and SI-F (gray line) were stained with an anti-F protein MAb (right panel). All the cells were subsequently stained with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody. The cells without transfection were stained with an anti-H protein MAb or an anti-F protein MAb followed by an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (shaded regions). (C) Diagrams of the chimeric F proteins. There are 10 amino acid differences (shown by vertical lines) between IC-F and SI-F. The regions derived from SI-F are shaded, and those derived from IC-F are white. The restriction enzyme-replaced fragments are indicated. (D) Syncytium formation in cells expressing the chimeric or mutant F proteins. CHO/hSLAM cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing IC-H together with plasmids expressing IC-F protein, SI-F protein, chimeric F protein (IC/SI-F-1, -F-2, -F-3, or -F-4), or mutant SI-F protein (G300E). At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were observed under a phase-contrast imaging microscope after Giemsa staining. (E) Quantification of syncytium formation. CHO/hSLAM cells were transfected with IC-H-expressing plasmids and IC-F-, SI-F-, chimeric F-, or mutant F-expressing plasmids together with an mCherry-expressing plasmid. At 48 h posttransfection, areas of each syncytium with mCherry autofluorescence were measured using an Axio Observer.D1 microscope and ImageJ software. Forty syncytia were measured for each F protein. Asterisks indicate that the area of syncytia induced by IC-F, chimeric F, or mutant F was significantly larger than that induced by SI-F, based on the results of a t test (P < 0.001). The horizontal bars indicate the median values of the areas of syncytia.

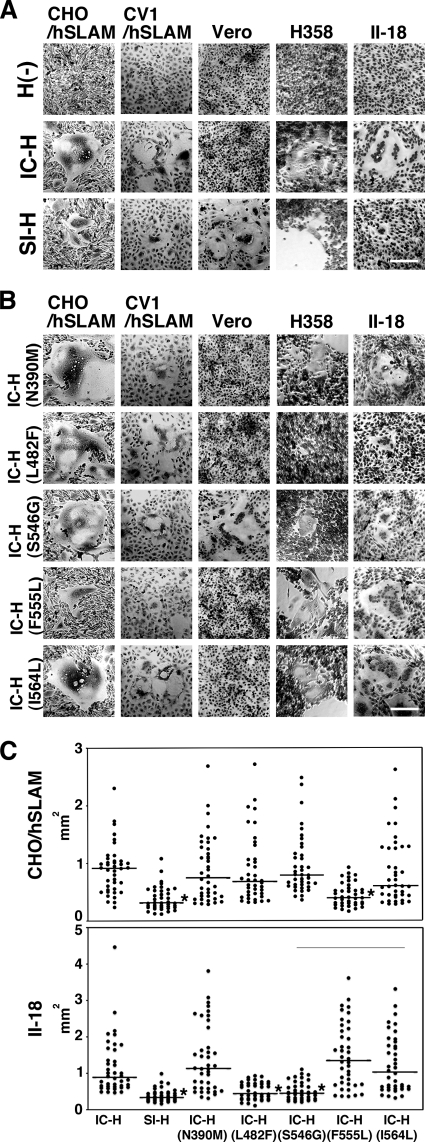

S546G, L482F, and F555L substitutions affected the fusion-helper function of the H protein.

To analyze the fusion-helper function of SI-H in different cell types, the protein was expressed in CHO/hSLAM (SLAM+), CV1/hSLAM (SLAM+, CD46+), Vero (CD46+), H358 (ECR+, CD46+), and II-18 (ECR+, CD46+) cells together with IC-F. CD46-dependent infection was blocked by an anti-CD46 antibody (M75) when CV1/hSLAM, H358, and II-18 cells were used for the assessment of SLAM- and ECR-dependent infection. IC-H was used as a control. When IC-F was expressed alone, no syncytia were observed in either cell line [Fig. 7A; H(−)]. As reported previously, IC-H supported cell-to-cell fusion efficiently in SLAM-positive (CHO/hSLAM) and ECR-positive (H358 and II-18) cells but not in Vero cells (Fig. 7A; IC-H) (45, 49, 59). SI-H exhibited a fusion-helper function in Vero cells (Fig. 7A; SI-H), probably because of the S546G substitution. However, SI-H supported cell-to-cell fusion less efficiently than IC-H in CHO/hSLAM, CV1/hSLAM, H358, and II-18 cells (Fig. 7A; SI-H). To identify the substitution(s) responsible for the altered fusion-helper function of SI-H, five substitutions were individually introduced into IC-H and the mutated proteins were expressed in cells together with IC-F. The five selected substitutions were N390M, L482F, S546G, F555L, and 564L, since these substitutions were unique to the SI strain and located in the receptor-binding globular head domain (Table 4). As expected, IC-H with S546G, but not the other mutant H proteins, supported cell-to-cell fusion in Vero cells (Fig. 7B). Instead, IC-H with S546G showed a reduced fusion-helper function in H358 and II-18 cells (Fig. 7B). No significant changes were observed in CHO/hSLAM and CV1/hSLAM cells after the introduction of the S546G substitution (Fig. 7B). Similarly, IC-H with L482F showed a reduced fusion-helper function in H358 and II-18 cells but showed activities similar to those seen with IC-H in CHO/hSLAM and CV1/hSLAM cells (Fig. 7B). Quantified and statistical analyses of cell-to-cell fusion in II-18 cells indicated that the areas of syncytia produced by IC-H(S546G) and IC-H(L482F) were significantly smaller than those produced by IC-H (P < 0.01) (Fig. 7C). None of the N390M, F555L, and I564L substitutions significantly affected the fusion-helper function in H358 and II-18 cells (Fig. 7B and C). These findings suggested that the L482F and S546G substitutions compromised the ability of the H protein to interact with ECR. It was also noted that the H protein with F555L showed a reduction in the fusion-helper function in CHO/hSLAM and CV1/hSLAM cells (Fig. 7B and C).

Fig. 7.

Characterization of the amino acid residues in the SI-H protein that support cell-to-cell fusion in cells expressing SLAM, CD46, or ECR. (A and B) CHO/hSLAM, CV1/hSLAM, Vero, H358, and II-18 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing the H protein of the IC-B or SI strain (IC-H or SI-H, respectively) or no H protein [H(−)] (A) or mutant IC-H protein (N390M, L482F, S546G, F555L, or I564L) (B) together with a plasmid expressing the F protein of the IC-B strain. The CV1/hSLAM, H358, and II-18 cells were then incubated with an anti-CD46 MAb (M75). At 1 (CHO/hSLAM and CV1/hSLAM), 2 (Vero and II-18), or 3 (H358) days posttransfection, the cells were observed under a phase-contrast imaging microscope after Giemsa staining. Bars, 0.2 mm. (C) Quantification of syncytium formation. CHO/hSLAM and II-18 cells were transfected with IC-F-expressing plasmids and IC-H-, SI-H-, or mutant H-expressing plasmids together with an mCherry-expressing plasmid. At 48 h posttransfection, areas of each syncytium with mCherry autoflurescence were measured using an Axio Observer.D1 microscope and ImageJ software. Forty syncytia were measured for each H protein. Asterisks indicate that the area of syncytia induced by SI-H or mutant H was significantly smaller than that induced by the IC-H, based on the results of a t test (P < 0.001). The horizontal bars indicate the median values of the areas of syncytia.

DISCUSSION

SLAM is expressed on cells of the immune system and functions as the principal receptor for MV infection (69). However, this molecule probably plays a minor role in MV growth in the CNS, because neural cells in the brain do not express SLAM (28). Indeed, the ability of the SI strain to use SLAM was compromised by the F555L substitution. We and another group recently demonstrated that certain epithelial cells that form tight junctions are highly susceptible to MV infection (25, 50, 59). These data demonstrated the existence of ECR on some epithelial cells (25, 50, 59). ECR probably contributes to the efficient transmission of MV from a patient to other individuals (53), but its roles in persistent infection of the brain with MV remain to be elucidated. ECR is a candidate for an MV receptor in the brain. However, our data indicated that the SI strain had mutated via the S546G and L482F substitutions to use ECR inefficiently. With these data, the idea that ECR functions as a receptor for MV in the brain seemed unconvincing. Instead, the SI-H protein had adapted to use CD46 via the S546G substitution. Woelk et al. identified several positive-selection amino acid sites in the SSPE strain (67), but S546G was absent from the list. It is possible that the S546G substitution was introduced into the SI strain genome during the propagation in Vero cells but not in the brain, since the SI strain was isolated using Vero cells (29). Vero cells are 100 to 1,000 times less sensitive than SLAM-positive B95a cells for the isolation of wt MV strains (22, 34), and wt MV strains readily adapt to use CD46 after several passages in Vero cells (69). However, Ogura et al. (34) indicated that Vero cells were more sensitive than B95a cells for the isolation of SSPE strains. Although their data demonstrated that SSPE strains show cell specificities different from those of wt MV strains, some SSPE strains were shown not to use CD46 as a receptor (47). Nevertheless, it is still possible that the acquisition of the ability to use CD46 contributes to the growth of some SSPE-derived strains in the brain, since various SSPE strains may employ different strategies to acquire the ability to spread in the brain. The SI strain used only CD46 efficiently. Much evidence obtained using CD46-transgenic mice has shown the contributions of CD46 in establishing MV infection of the brain. Analyses using human brain samples also showed that CD46 is a candidate molecule that contributes to the growth of some SSPE strains in the brain (5, 28, 33).

Analyses using animal models have demonstrated that MV uses a transsynaptic route to spread between neurons (24, 27, 35, 40). The data indicated that receptors for the H protein are not required for the transsynaptic transmission (27, 70). It has been suggested that the F protein causes microfusion between neurons without the support of the H protein (27, 70). Ayata et al. (1) demonstrated that the F proteins of some SSPE strains contribute to the exhibition of neurovirulence in animals by showing a hyperfusion activity. Cattaneo et al. (4, 8) also demonstrated that the F proteins of SSPE strains exhibit higher levels of fusion activities than the standard F protein. These data suggest an important role for the F protein in the propagation of SSPE strains in the brain. However, our data indicated that the F protein of the SI strain showed limited membrane fusion activity because of the E300G substitution. It is unlikely that the F protein of the SI strain had acquired the E300G substitution during the propagation in cultured cells, since viruses usually acquire mutations that confer better fitness. Consequently, our data suggest that a high level of membrane fusion activity of the F protein was not a prerequisite for this SSPE strain to spread in the brain. Watanabe et al. (65) suggested that a reduction in cell-to-cell fusion mediated by amino acid changes in the F protein contributes to the persistence of MV in the brain. Their observations are consistent with our data for the SI strain. Thus, the data obtained in the present study provide a clear example of an SSPE-derived strain that exhibits limited fusion activity.

In the present study, we also established a reverse genetics system for the SI strain. Although we previously reported very efficient reverse genetics systems for MV, as shown using recombinant vaccinia viruses encoding T7 RNA polymerase (VV-T7) (30, 55, 56), they were not applicable for rescue of the SI strain from cloned cDNAs. When the previous systems were used (30, 56), infectious cycles of rSI-AcGFP were efficiently initiated in CHO/hSLAM cells by the use of the full-length genome plasmid (data not shown). However, since rSI-AcGFP did not produce cell-free virus particles and replicated poorly, it was impossible to isolate rSI-AcGFP from VV-T7. We tried to use a VV-T7-free system reported by Radecke et al. (39), but neither syncytia nor AcGFP fluorescence was detected. Therefore, a new, efficient VV-T7-free system was required for the rescue of rSI-AcGFP from cloned cDNAs. We are convinced that this new system used for the SI strain would be applicable for other SSPE strains. The success in establishing a reverse genetics system for an SSPE strain is a significant step toward the elucidation of the molecular bases and pathogenesis of SSPE.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank T. A. Sato and T. Seya for providing MAbs and N. Ito and M. Sugiyama for providing the BHK/T7-9 cells. We also thank K. Maenaka and all the members of Department of Virology 3, NIID, Japan, for technical help and suggestions.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan and a grant from The Uehara Memorial Foundation.

Footnotes

Present address: Research Promotion Project, Oita University, Oita, Japan.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 14 September 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ayata M., et al. 2007. Effect of the alterations in the fusion protein of measles virus isolated from brains of patients with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis on syncytium formation. Virus Res. 130: 260–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baricevic M., Forcic D., Santak M., Mazuran R. 2007. A comparison of complete untranslated regions of measles virus genomes derived from wild-type viruses and SSPE brain tissues. Virus Genes 35: 17–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bellini W. J., et al. 2005. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: more cases of this fatal disease are prevented by measles immunization than was previously recognized. J. Infect. Dis. 192: 1686–1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Billeter M. A., et al. 1994. Generation and properties of measles virus mutations typically associated with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 724: 367–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buchholz C. J., et al. 1996. Selective expression of a subset of measles virus receptor-competent CD46 isoforms in human brain. Virology 217: 349–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cathomen T., et al. 1998. A matrix-less measles virus is infectious and elicits extensive cell fusion: consequences for propagation in the brain. EMBO J. 17: 3899–3908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cathomen T., Naim H. Y., Cattaneo R. 1998. Measles viruses with altered envelope protein cytoplasmic tails gain cell fusion competence. J. Virol. 72: 1224–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cattaneo R., Rose J. K. 1993. Cell fusion by the envelope glycoproteins of persistent measles viruses which caused lethal human brain disease. J. Virol. 67: 1493–1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cattaneo R., et al. 1988. Biased hypermutation and other genetic changes in defective measles viruses in human brain infections. Cell 55: 255–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cattaneo R., et al. 1986. Accumulated measles virus mutations in a case of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: interrupted matrix protein reading frame and transcription alteration. Virology 154: 97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cattaneo R., et al. 1989. Mutated and hypermutated genes of persistent measles viruses which caused lethal human brain diseases. Virology 173: 415–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Griffin D. E. 2007. Measles virus, p. 1551–1585. In Knipe D. M., et al. (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grosfeld H., Hill M. G., Collins P. L. 1995. RNA replication by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is directed by the N, P, and L proteins; transcription also occurs under these conditions but requires RSV superinfection for efficient synthesis of full-length mRNA. J. Virol. 69: 5677–5686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hall W. W., Choppin P. W. 1979. Evidence for lack of synthesis of the M polypeptide of measles virus in brain cells in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Virology 99: 443–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hall W. W., Choppin P. W. 1981. Measles-virus proteins in the brain tissue of patients with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: absence of the M protein. N. Engl. J. Med. 304: 1152–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hall W. W., Lamb R. A., Choppin P. W. 1979. Measles and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis virus proteins: lack of antibodies to the M protein in patients with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 76: 2047–2051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Halsey N. A., et al. 1980. Risk factors in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: a case-control study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 111: 415–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hirano A., Wang A. H., Gombart A. F., Wong T. C. 1992. The matrix proteins of neurovirulent subacute sclerosing panencephalitis virus and its acute measles virus progenitor are functionally different. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89: 8745–8749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ishida H., et al. 2004. Infection of different cell lines of neural origin with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) virus. Microbiol. Immunol. 48: 277–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ito N., et al. 2003. Improved recovery of rabies virus from cloned cDNA using a vaccinia virus-free reverse genetics system. Microbiol. Immunol. 47: 613–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kato A., et al. 1996. Initiation of Sendai virus multiplication from transfected cDNA or RNA with negative or positive sense. Genes Cells 1: 569–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kobune F., Sakata H., Sugiura A. 1990. Marmoset lymphoblastoid cells as a sensitive host for isolation of measles virus. J. Virol. 64: 700–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Komase K., et al. 2006. The phosphoprotein of attenuated measles AIK-C vaccine strain contributes to its temperature-sensitive phenotype. Vaccine 24: 826–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lawrence D. M., et al. 2000. Measles virus spread between neurons requires cell contact but not CD46 expression, syncytium formation, or extracellular virus production. J. Virol. 74: 1908–1918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leonard V. H., et al. 2008. Measles virus blind to its epithelial cell receptor remains virulent in rhesus monkeys but cannot cross the airway epithelium and is not shed. J. Clin. Invest. 118: 2448–2458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leyrer S., Neubert W. J., Sedlmeier R. 1998. Rapid and efficient recovery of Sendai virus from cDNA: factors influencing recombinant virus rescue. J. Virol. Methods 75: 47–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Makhortova N. R., et al. 2007. Neurokinin-1 enables measles virus trans-synaptic spread in neurons. Virology 362: 235–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McQuaid S., Cosby S. L. 2002. An immunohistochemical study of the distribution of the measles virus receptors, CD46 and SLAM, in normal human tissues and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Lab. Invest. 82: 403–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mirchamsy H., et al. 1978. Isolation and characterization of a defective measles virus from brain biopsies of three patients in Iran with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Intervirology 9: 106–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nakatsu Y., Takeda M., Kidokoro M., Kohara M., Yanagi Y. 2006. Rescue system for measles virus from cloned cDNA driven by vaccinia virus Lister vaccine strain. J. Virol. Methods 137: 152–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ning X., et al. 2002. Alterations and diversity in the cytoplasmic tail of the fusion protein of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis virus strains isolated in Osaka, Japan. Virus Res. 86: 123–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Niwa H., Yamamura K., Miyazaki J. 1991. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene 108: 193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ogata A., et al. 1997. Absence of measles virus receptor (CD46) in lesions of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis brains. Acta Neuropathol. 94: 444–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ogura H., et al. 1997. Efficient isolation of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis virus from patient brains by reference to magnetic resonance and computed tomographic images. J. Neurovirol. 3: 304–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oldstone M. B. A., et al. 1999. Measles virus infection in a transgenic model: virus-induced immunosuppression and central nervous system disease. Cell 98: 629–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ono N., et al. 2001. Measles viruses on throat swabs from measles patients use signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (CDw150) but not CD46 as a cellular receptor. J. Virol. 75: 4399–4401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Parks C. L., et al. 2001. Comparison of predicted amino acid sequences of measles virus strains in the Edmonston vaccine lineage. J. Virol. 75: 910–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Radecke F., Billeter M. A. 1995. Appendix: measles virus antigenome and protein consensus sequences. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 191: 181–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Radecke F., et al. 1995. Rescue of measles viruses from cloned DNA. EMBO J. 14: 5773–5784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rall G. F., et al. 1997. A transgenic mouse model for measles virus infection of the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94: 4659–4663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Richardson C. D., Scheid A., Choppin P. W. 1980. Specific inhibition of paramyxovirus and myxovirus replication by oligopeptides with amino acid sequences similar to those at the N-termini of the F1 or HA2 viral polypeptides. Virology 105: 205–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sato T. A., Fukuda A., Sugiura A. 1985. Characterization of major structural proteins of measles virus with monoclonal antibodies. J. Gen. Virol. 66: 1397–1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sato T. A., Hayami M., Yamanouchi K. 1981. Antibody response to structural proteins of measles virus in patients with natural measles and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Jpn. J. Med. Sci. Biol. 34: 365–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schmid A., et al. 1992. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis is typically characterized by alterations in the fusion protein cytoplasmic domain of the persisting measles virus. Virology 188: 910–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Seki F., Takeda M., Minagawa H., Yanagi Y. 2006. Recombinant wild-type measles virus containing a single N481Y substitution in its haemagglutinin cannot use receptor CD46 as efficiently as that having the haemagglutinin of the Edmonston laboratory strain. J. Gen. Virol. 87: 1643–1648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Seya T., et al. 1995. Blocking measles virus infection with a recombinant soluble from of, or monoclonal antibodies against, membrane cofactor protein of complement (CD46). Immunology 84: 619–625 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shingai M., et al. 2003. Receptor use by vesicular stomatitis virus pseudotypes with glycoproteins of defective variants of measles virus isolated from brains of patients with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. J. Gen. Virol. 84: 2133–2143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shirogane Y., et al. 2008. Efficient multiplication of human metapneumovirus in Vero cells expressing the transmembrane serine protease TMPRSS2. J. Virol. 82: 8942–8946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shirogane Y., et al. 2010. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition abolishes the susceptibility of polarized epithelial cell lines to measles virus. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 20882–20890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tahara M., et al. 2008. Measles virus infects both polarized epithelial and immune cells by using distinctive receptor-binding sites on its hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 82: 4630–4637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tahara M., Takeda M., Yanagi Y. 2005. Contributions of matrix and large protein genes of the measles virus Edmonston strain to growth in cultured cells as revealed by recombinant viruses. J. Virol. 79: 15218–15225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Takasu T., et al. 2003. A continuing high incidence of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) in the Eastern Highlands of Papua New Guinea. Epidemiol. Infect. 131: 887–898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Takeda M. 2008. Measles virus breaks through epithelial cell barriers to achieve transmission. J. Clin. Invest. 118: 2386–2389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Takeda M., et al. 1998. Measles virus attenuation associated with transcriptional impediment and a few amino acid changes in the polymerase and accessory proteins. J. Virol. 72: 8690–8696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Takeda M., et al. 2006. Generation of measles virus with a segmented RNA genome. J. Virol. 80: 4242–4248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Takeda M., et al. 2005. Efficient rescue of measles virus from cloned cDNA using SLAM-expressing Chinese hamster ovary cells. Virus Res. 108: 161–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Takeda M., et al. 2005. Long untranslated regions of the measles virus M and F genes control virus replication and cytopathogenicity. J. Virol. 79: 14346–14354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Takeda M. 2008. Measles viruses possessing the polymerase protein genes of the Edmonston vaccine strain exhibit attenuated gene expression and growth in cultured cells and SLAM knock-in mice. J. Virol. 82: 11979–11984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Takeda M., et al. 2007. A human lung carcinoma cell line supports efficient measles virus growth and syncytium formation via a SLAM- and CD46-independent mechanism. J. Virol. 81: 12091–12096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Takeda M., et al. 2000. Recovery of pathogenic measles virus from cloned cDNA. J. Virol. 74: 6643–6647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Takeuchi K., Miyajima N., Kobune F., Tashiro M. 2000. Comparative nucleotide sequence analysis of the entire genomes of B95a cell-isolated and Vero cell-isolated measles viruses from the same patient. Virus Genes 20: 253–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tatsuo H., Ono N., Tanaka K., Yanagi Y. 2000. SLAM (CDw150) is a cellular receptor for measles virus. Nature 406: 893–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22: 4673–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wang D., Zhang Y., Zhang Z., Zhu J., Yu J. 2010. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: a toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 8: 77–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Watanabe M., et al. 1995. Delayed activation of altered fusion glycoprotein in a chronic measles virus variant that causes subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. J. Neurovirol. 1: 177–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. WHO. 2003. Update of the nomenclature for describing the genetic characteristics of wild-type measles viruses: new genotypes and reference strains. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 78: 229–232 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Woelk C. H., Pybus O. G., Jin L., Brown D. W., Holmes E. C. 2002. Increased positive selection pressure in persistent (SSPE) versus acute measles virus infections. J. Gen. Virol. 83: 1419–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wong T. C., et al. 1989. Generalized and localized biased hypermutation affecting the matrix gene of a measles virus strain that causes subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. J. Virol. 63: 5464–5468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Yanagi Y., Takeda M., Ohno S., Hashiguchi T. 2009. Measles virus receptors. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 329: 13–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Young V. A., Rall G. F. 2009. Making it to the synapse: measles virus spread in and among neurons. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 330: 3–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.