Abstract

Newcastle disease virus (NDV)-induced membrane fusion requires an interaction between the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (HN) attachment and the fusion (F) proteins, triggered by HN′s binding to receptors. NDV HN has two sialic acid binding sites: site I, which also mediates neuraminidase activity, and site II, which straddles the membrane-distal end of the dimer interface. By characterizing the effect on receptor binding avidity and F-interactive capability of HN dimer interface mutations, we present evidence consistent with (i) receptor engagement by site I triggering the interaction with F and (ii) site II functioning to maintain high-avidity receptor binding during the fusion process.

TEXT

Newcastle disease virus (NDV) is a member of the Paramyxoviridae family of negative-strand RNA viruses (12). These viruses enter and spread between cells by virus-cell and cell-cell fusion, respectively, triggered by receptor binding. However, receptor binding and fusion are mediated by two different glycoproteins, the attachment and fusion (F) proteins, respectively, requiring a mechanism by which the two processes can be linked. This is accomplished by a virus-specific interaction between the two proteins (9, 10, 13, 19).

The ectodomain of paramyxovirus attachment proteins, including the NDV hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (HN), consists of a long stalk connected to a terminal globular domain (12). Whereas the HN globular domain mediates binding to sialic acid receptors, the stalk mediates the interaction with the homologous F protein (5, 15, 16). However, the mechanism by which receptor binding triggers fusion is not well understood. The globular head consists of a six-bladed β-sheet propeller with a centrally located sialic acid binding site (site I) that also mediates neuraminidase (NA) activity (4). Many mutations in this site, including K236R, abolish receptor binding, NA, and fusion (7), as well as the ability of HN to interact with F at the cell surface (14). These findings, along with the results of bimolecular complementation studies (2), are consistent with HN and F promoting fusion by the provocateur (2) mechanism, which asserts that the HN-F interaction is triggered at the surface by receptor binding.

Takimoto et al. (20) identified several mutations in the dimer interface of NDV HN that severely compromised fusion promotion. Subsequently, we showed that the fusion deficiency resulting from many of these mutations in the membrane-proximal region of the interface, e.g., F220A and -N and S222A, -K, -N, and -T, correlated with impaired hemadsorption (HAd) activity at 37°C, despite wild-type (wt) NA activity (3). Modeling of this domain indicated that these mutations disrupted intermonomeric hydrogen bonds critical to the integrity of the dimer interface (3).

A second sialic acid binding site (site II) was subsequently identified at the membrane-distal end of the interface that is composed of residues from both monomers (21) and is proposed (1) to maintain the target membrane in close proximity during fusion. Here, we test the hypothesis that the HAd/fusion-deficient phenotype of these mutants results not from an inability to interact with F but from perturbation of the second binding site, resulting in an inability of HN to remain attached to the target cell.

To examine the relationship between receptor binding avidity, the F interaction, and fusion promotion, we determined the relative avidities of some of the interface mutants that exhibit reduced HAd at 37°C (3). wt and mutated HN proteins were expressed in BHK-21F cells (3), using the vaccinia virus-T7 RNA polymerase expression system (6). Guinea pig erythrocytes (Bio-Link Laboratories, Liverpool, NY) were treated with various concentrations of Vibrio cholerae neuraminidase (VCNA) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) for 1 h at 37°C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) to deplete them of sialic acid receptors to various extents (8). This generated a set of erythrocyte preparations having a gradient of receptor densities on their surfaces. The HN-expressing monolayers were washed with cold DMEM, incubated with the erythrocytes on ice for 30 min, and washed three times with cold DMEM. HAd activity was quantified at pH 7.2 spectrophotometrically (3).

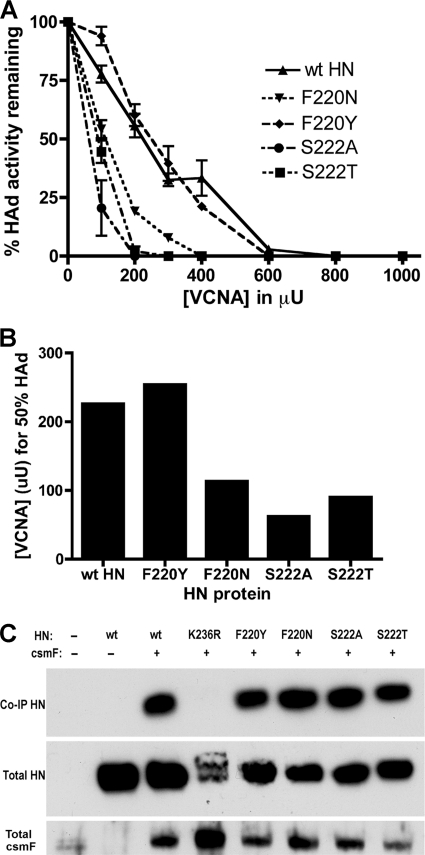

HN proteins carrying one of the interface mutations that cause the HAd/fusion-deficient phenotype (F220N, S222A, or S222T) and, as a control, one that is wt for these properties (F220Y) (3) were tested for the sensitivity of their HAd activities at 4°C to VCNA. Representative VCNA sensitivity curves for each mutated protein and wt HN are shown in Fig. 1A. Relative receptor binding avidity can be expressed as the concentration of VCNA that reduces HAd by 50% of the mock-treated control value (Fig. 1B). For wt HN, this is achieved with 226 μU of VCNA. For the control F220Y-mutated HN, the 50% point is reached after treatment with 254 μU of enzyme. However, the HAd activities of the fusion-deficient, F220N-, S222A-, and S222T-mutated proteins are reduced to 50% of the mock-treated control value at 113, 62, and 90 μU, respectively, a 2- to 4-fold increase in sensitivity, confirming that the fusion-deficient mutants bind sialic acid receptors with significantly reduced avidity.

Fig. 1.

Receptor binding avidity and F-interactive ability of HN dimer interface mutants. (A) Ability of wt HN and HN carrying an F220N, F220Y, S222A, or S222T mutation to mediate HAd of guinea pig erythrocytes pretreated with various concentrations of VCNA. Error bars represent the standard deviations from three data points from at least two experiments. (B) The concentration of VCNA that reduces the HAd activity of the HN protein to 50% of the mock-treated control value. (C) Ability of the interface mutants to interact with csmF at the cell surface as detected by a biotinylated co-IP-Western blotting assay. As a negative control, K236R-mutated HN does not bind receptors and does not interact with csmF (14). Total cell surface HN and csmF are also shown.

To determine the relationship between receptor binding avidity and the HN-F interaction, we examined the ability of the mutated HN proteins to interact with a cleavage site mutant form of F (csmF) at the surface of transfected BHK-21F cells, using a modification of a cell surface coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assay (15). Briefly, at 16 h posttransfection, surface proteins were biotinylated using membrane-impermeable sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) and the cells were lysed in DH buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.2], 10 mM dodecyl-β-d-maltoside [Affymetrix, Inc., Maumee, OH], 150 mM NaCl, Complete Mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN]). HN was immunoprecipitated through its interaction with csmF by using an F-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) (called Fbc) and detected by Western blotting using a MAb (called HN14f) that recognizes a linear epitope in HN (11). Total surface HN and F were quantitated by immunoprecipitation from aliquots of the lysate with HN14f and Fbc, respectively, and streptavidin beads followed by Western blotting using HN14f and a polyclonal antiserum to the cytoplasmic tail of F, for HN and F, respectively. All three fusion-deficient mutants retain the ability to interact with csmF in amounts comparable to those of wt HN, indicating that the mutations that likely disrupt the integrity of the dimer interface do not affect the ability of HN to interact with F (Fig. 1C). As a negative control, HN carrying a K236R mutation in site I fails to co-IP with F, as previously demonstrated (14).

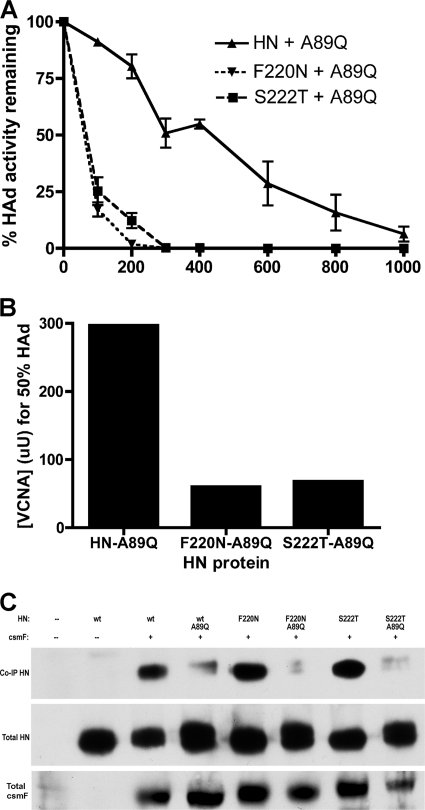

We have previously identified mutations for residues A89, L90, and L94 in the stalk of NDV HN, which modulate proportionately fusion and HN-F complex formation, consistent with this domain mediating the interaction with F (15). To confirm that this domain also mediates the interaction of the dimer interface mutants with F, we have prepared A89Q-F220N- and A89Q-S222T-mutated proteins and evaluated them in avidity (Fig. 2A and B) and co-IP (Fig. 2C) assays. First, we verified that the A89Q mutation did not alter the expression or HAd properties of the interface mutants, and as expected, the doubly mutated proteins exhibited negligible or no fusion-promoting activity (data not shown). Importantly, similarly to the individual F220N- and S222T-mutated proteins (Fig. 1A), the HAd activities of both double mutants exhibit markedly enhanced VCNA sensitivity (Fig. 2A) with the 50% point for A89Q-F220N achieved at 60 μU VCNA and that for A89Q-S222T achieved at 68 μU, compared to 297 μU for A89Q-mutated HN (Fig. 2B). The latter protein exhibited severely compromised fusion-promoting activity (16.7% of wt value) and no detectable co-IP with F (15). Similarly, the double mutants also co-IP negligibly with F at the cell surface (Fig. 2C), confirming that the interaction of the interface mutants with F is mediated by the same domain as it is in wt HN.

Fig. 2.

Receptor binding avidity and F-interactive capability of HN dimer interface mutants carrying a stalk mutation that interferes with the ability of the protein to interact with the F protein. (A) Ability of HN and F220N and S222T mutants carrying an A89Q mutation in the stalk to mediate HAd of guinea pig erythrocytes previously treated with various concentrations of VCNA (x axis, in microunits). Error bars represent the standard deviations from three data points from at least two experiments. (B) The concentration of VCNA that reduces the HAd activity of the HN protein to 50% of the mock-treated control value. (C) Ability of the same proteins to interact with csmF at the cell surface. Total cell surface HN and csmF are also shown in aliquots from each sample.

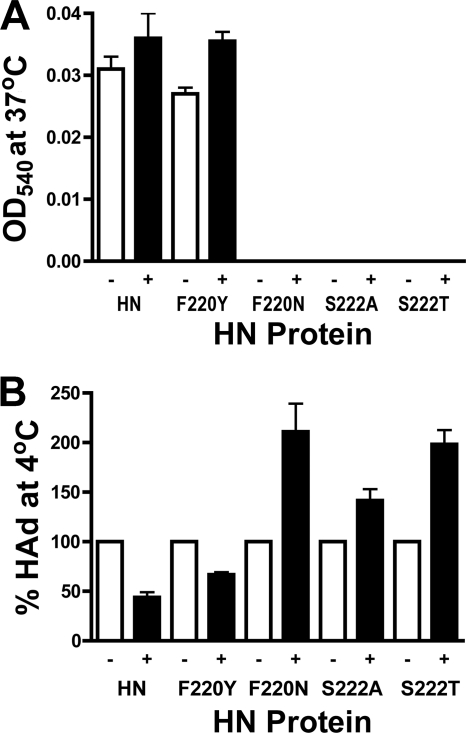

Based on these findings, we propose that the HAd deficiency of the dimer interface mutants at 37°C is due to perturbation of the second sialic acid binding site. To probe the status of this site in the mutants, we compared the effects of the NA inhibitor 4-guanidino-NeuAc2en (zanamivir) on the HAd activities of each of the mutants with that of wt HN. Zanamivir binds in the NA active site and blocks its ability to act as a binding site but has negligible affinity for site II (18). Indeed, it has been shown that binding of zanamivir to the first site activates the second site for binding (17). Zanamivir was prepared from Relenza Rotadisks (5 mg zanamivir with lactose). A 50 mM stock solution was prepared by dissolving the capsule in 285 μl of DMEM, and the stock solution was stored at −20°C. HN-expressing cells were treated with 5 mM zanamivir for 30 min at room temperature. After removal of zanamivir, HAd activity was determined at 37°C (Fig. 3A) and 4°C (Fig. 3B) and compared to the mock-treated controls. At 37°C, the HAd activity of the wt and F220Y-mutated proteins is enhanced by treatment with zanamivir, consistent with activation of site II (17). However, the F220N-, S222A-, and S222T-mutated proteins are null for HAd at this temperature even after zanamivir treatment (Fig. 3A), consistent with these mutants lacking a functional second site at 37°C.

Fig. 3.

Effect of zanamivir on the HAd activity of wt HN and the dimer interface mutants at 37°C and at 4°C. Cells were treated with 5 mM zanamivir in DMEM or mock treated for 30 min at room temperature. After removal of the inhibitor, HAd activity was assayed. (A) The HAd activity at 37°C expressed as optical density at 540 nm (OD540) is shown with and without pretreatment with zanamivir. Error bars represent the standard deviations from two data points from a representative experiment. (B) The percent HAd activity at 4°C following treatment with zanamivir relative to that of the mock-treated control. Error bars represent the standard deviations from four data points from a representative experiment.

However, at 4°C, at which there is no NA activity, whereas zanamivir inhibited the HAd activity of both wt and F220Y-mutated HN, it significantly enhanced that of all three fusion-deficient interface mutants, two of them more than 2-fold (Fig. 3B). We propose that, at 4°C, the intact dimer interface in wt and F220Y-mutated HN is hyperstabilized and restricts the changes necessary for activation of site II and these proteins exhibit decreased HAd relative to the mock-treated control. In this case, zanamivir is competing with receptor for binding to the first site. Paradoxically, the mutants with a weakened dimer interface are restabilized enough in the cold to be capable of undergoing the necessary conformational changes to activate the second site such that the protein binds receptors more efficiently than the mock-treated control. Thus, it appears that the interface mutations destabilize the second binding site at 37°C, although it is intact at 4°C.

Our findings suggest that the HAd/fusion deficiency of the dimer interface mutants is due to disruption of the second sialic acid binding site at the opposite end of the interface and support a mechanism of fusion in which (i) engagement of receptor by site I triggers the interaction with F and (ii) site II functions to maintain contact with the target cell during fusion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rebecca Dutch for the BHK-21F cells, Bernard Moss for the vTF7-3 virus, Robert Lamb for the NDV F gene, Trudy Morrison for the NDV HN gene, and Mark Peeples for the antiserum to the F cytoplasmic tail.

This work was supported by grant AI-49268 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 August 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bousse T. L., et al. 2004. Biological significance of the second receptor binding site of Newcastle disease virus hemagglutinin-neuraminidase protein. J. Virol. 78: 13351–13355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Connolly S. A., Leser G. P., Jardetzky T. S., Lamb R. A. 2009. Bimolecular complementation of paramyxovirus fusion and hemagglutinin-neuraminidase proteins enhances fusion: implications for the mechanism of fusion triggering. J. Virol. 83: 10857–10868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Corey E. A., Mirza A. M., Levandowsky E., Iorio R. M. 2003. Fusion deficiency induced by mutations at the dimer interface in the Newcastle disease virus hemagglutinin-neuraminidase is due to a temperature-dependent defect in receptor binding. J. Virol. 77: 6913–6922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crennell S., Takimoto T., Portner A., Taylor G. 2000. Crystal structure of the multifunctional paramyxovirus hemagglutinin-neuraminidase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7: 1068–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deng R., Wang Z., Mirza A. M., Iorio R. M. 1995. Localization of a domain on the paramyxovirus attachment protein required for the promotion of cellular fusion by its homologous fusion protein spike. Virology 209: 457–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fuerst T. R., Niles E. G., Studier F. W., Moss B. 1986. Eucaryotic transient expression system based on recombinant vaccinia virus that synthesizes bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83: 8122–8126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iorio R. M., et al. 2001. Structural and functional relationship between the receptor recognition and neuraminidase activities of the Newcastle disease virus hemagglutinin-neuraminidase protein: receptor recognition is dependent on neuraminidase activity. J. Virol. 75: 1918–1927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iorio R. M., Glickman R. L. 1992. Fusion mutants of Newcastle disease virus selected with monoclonal antibodies to the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase. J. Virol. 66: 6626–6633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iorio R. M., Mahon P. J. 2008. Paramyxoviruses: different receptors—different mechanisms of fusion. Trends Microbiol. 16: 135–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iorio R. M., Melanson V. R., Mahon P. J. 2009. Glycoprotein interactions in paramyxovirus fusion. Future Virol. 4: 335–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iorio R. M., et al. 1991. Neutralization map of the HN glycoprotein of Newcastle disease virus: domains recognized by monoclonal antibodies that prevent receptor recognition activity. J. Virol. 65: 4999–5006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lamb R. A., Parks G. D. 2007. Paramyxoviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 1449–1496 In Knipe D. M., et al. (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee B., Ataman Z. A. 2011. Modes of paramyxovirus fusion; a Henipavirus perspective. Trends Microbiol. 19: 389–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li J., Quinlan E., Mirza A., Iorio R. M. 2004. Mutated form of the Newcastle disease virus hemagglutinin-neuraminidase interacts with the homologous fusion protein despite deficiencies in both receptor recognition and fusion promotion. J. Virol. 78: 5299–5310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Melanson V. R., Iorio R. M. 2004. Amino acid substitutions in the F-specific domain in the stalk of the Newcastle disease virus HN protein modulate fusion and interfere with its interaction with the F protein. J. Virol. 78: 13053–13061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Melanson V. R., Iorio R. M. 2006. Addition of N-glycans in the stalk of the Newcastle disease virus HN protein blocks its interaction with the F protein and prevents fusion. J. Virol. 80: 623–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Porotto M., et al. 2006. Paramyxovirus receptor-binding molecules: engagement of one site on the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase protein modulates activity at the second site. J. Virol. 80: 1204–1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Porotto M., et al. 2004. Inhibition of parainfluenza virus type 3 and Newcastle disease virus hemagglutinin-neuraminidase receptor binding: effect of receptor avidity and steric hindrance at the inhibitor binding sites. J. Virol. 78: 13911–13919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith E. C., Popa A., Chang A., Masante C., Dutch R. E. 2009. Viral entry mechanisms; the increasing diversity of paramyxovirus entry. FEBS J. 276: 7217–7227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Takimoto T., Taylor G. L., Connaris H. C., Crennell S. J., Portner A. 2002. Role of the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase protein in the mechanism of paramyxovirus-cell membrane fusion. J. Virol. 76: 13028–13033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zaitsev V., et al. 2004. Second sialic acid binding site in Newcastle disease virus hemagglutinin-neuraminidase: implications for fusion. J. Virol. 78: 3733–3741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]