Abstract

The Mre11 complex is a central component of the DNA damage response, with roles in damage sensing, molecular bridging, and end resection. We have previously shown that in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Ku70 (yKu70) deficiency reduces the ionizing radiation sensitivity of mre11Δ mutants. In this study, we show that yKu70 deficiency suppressed the camptothecin (CPT) and methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) sensitivity of nuclease-deficient mre11-3 and sae2Δ mutants in an Exo1-dependent manner. CPT-induced G2/M arrest, γ-H2AX persistence, and chromosome breaks were elevated in mre11-3 mutants. These outcomes were reduced by yKu70 deficiency. Given that the genotoxic effects of CPT are manifest during DNA replication, these data suggest that Ku limits Exo1-dependent double-strand break (DSB) resection during DNA replication, inhibiting the initial processing steps required for homology-directed repair. We propose that Mre11 nuclease- and Sae2-dependent DNA end processing, which initiates DSB resection prevents Ku from engaging DSBs, thus promoting Exo1-dependent resection. In agreement with this idea, we show that Ku affinity for binding to short single-stranded overhangs is much lower than for blunt DNA ends. Collectively, the data define a nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ)-independent, S-phase-specific function of the Ku heterodimer.

INTRODUCTION

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are repaired via two general mechanisms: nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) and homology-directed repair (HDR). HDR is initiated through processing and resection of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) ends to generate 3′ single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhangs that ultimately invade homologous duplex DNA, most often a sister chromatid. Recent in vivo data suggest a two-step mechanism for DSB resection in mitotic cells. First, 50- to 100-base 3′ ssDNA overhangs are generated by Sae2 and the Mre11 complex, which consists of Mre11, Rad50, and Xrs2. Both Mre11 and Sae2 specify nuclease activities capable of mediating the first incision to generate ssDNA overhangs (31, 54, 64, 66). In the second step, two pathways effect bulk resection: Sgs1, in conjunction with Dna2, and the Exo1 nuclease (17, 42, 72). The in vitro requirements for DSB resection are generally consistent with the in vivo data (7, 49, 50) although the initial incision step observed in vivo is not modeled in the in vitro reaction.

Mre11 nuclease activity and Sae2 influence the processing of complex DNA ends. Mre11 nuclease-deficient and sae2Δ diploids fail to sporulate due to a defect in the endonucleolytic removal of covalent Spo11 from meiotic DSBs (24, 25, 45, 48). mre11Δ, mre11 nuclease, and sae2Δ mutants exhibit sensitivity to camptothecin (CPT) (11, 32, 67), which traps covalent topoisomerase 1 (Top1)-DNA cleavable complexes and induces DNA replication-dependent cell death (15, 19, 56, 59), suggesting that Mre11 and Sae2 may promote the removal of Top1-DNA adducts (11). In addition, mre11 nuclease and sae2Δ mutants are sensitive to high levels of methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) and ionizing radiation (IR) (5, 21, 29, 38, 45), supporting the view that Mre11 and Sae2 may process chemically complex DNA termini to create appropriate substrates for DSB repair enzymes such as those required for DSB resection and ligation.

Additional aspects of Mre11 and Sae2 deficiency support the interpretation that their activities are relevant for the removal of aberrant DNA structures. For example, the Mre11 nuclease and Sae2 cleave hairpin structures in vivo and in vitro (31, 33, 54, 63, 70). Unlike Mre11, sae2 alleles separating hairpin opening and Spo11 removal by Sae2 have been identified, suggesting that Sae2 influences more than one activity at complex DNA ends (26). Mre11 nuclease or Sae2 deficiency also confers synthetic lethality with deletion of the gene encoding the Okazaki fragment processing nuclease, Rad27 (10, 45). Though the mechanism of toxicity is unclear, EXO1 overexpression partially restores mre11Δ rad27Δ viability (46), suggesting that lethality is associated with a lesion that can be repaired in an Exo1-dependent manner.

We report here that deficiency of budding yeast Ku70 (yKu70), a component of the yKu70-yKu80 heterodimer, which binds DNA ends and hairpins (2, 13, 52), suppresses the CPT and MMS sensitivity of mre11 nuclease and sae2Δ mutants. CPT treatment of mre11 nuclease mutants induces persistent G2/M arrest, γ-H2AX signal, chromosome breaks, and hyperrecombination, all of which are reduced by yKu70 deficiency. The yku70Δ-dependent rescue requires Exo1, suggesting that yKu70 normally antagonizes a DSB repair process in S-phase cells requiring Mre11 nuclease activity, Sae2, and Exo1. Supporting a role for Ku in S phase, we find that yKu70 deficiency also suppresses the synthetic lethality conferred by Mre11 nuclease and Rad27 deficiency. We show that Ku binds poorly to duplex DNA containing 30-base ssDNA overhangs, such as those created by Mre11 or Sae2, suggesting that the Mre11 nuclease and Sae2 process DSBs to prohibit Ku-mediated inhibition of HDR. Taken together, our data highlight two novel findings. First, Mre11 nuclease activity is critical for mitotic DSB repair. Second, by using agents and mutants that induce DSBs in S phase, our experiments support the idea that the Mre11 nuclease and Ku regulate the processing of DNA damage arising during DNA replication and thereby influence the mode by which these lesions are repaired.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and plasmids.

All strains used in this study are in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae W303 background (Table 1). Deletions of YKU70, DNL4, and EXO1 were generated by standard techniques of PCR-based disruption using pFA vectors (34). To generate mre11-3 strains (5), full-length mre11-3::URA3 (mre11-H125L/D126V) was generated by BamHI digestion of pTAP8-mre11-3::URA3 and integrated at the endogenous MRE11 locus. pRS304-top1-T722A-FLAG3 was generated by site-directed mutagenesis of pRS304-TOP1-FLAG3 (contains the 3′ coding region of TOP1) (37). The top1-T722A-FLAG3 strain was generated by integration at the endogenous TOP1 locus of SpeI-digested pRS304-top1-T722A-FLAG3. Plasmid and primer details are available upon request. Haploid strains containing two or more mutations were generated by sporulation and dissection of heterozygous diploids.

Table 1.

Yeast strains

| Strain | Genotype | Source; reference |

|---|---|---|

| JPY708 | MATa WT | Petrini laboratory |

| JPY1216 | MATaexo1Δ::KANMX6 | Petrini laboratory |

| JPY2252 | MATasae2Δ::KANMX6 | Petrini laboratory; 26 |

| JPY2258 | MATα sae2Δ::HYG | Petrini laboratory |

| JPY2421 | MATa/MATα rad50Δ/rad50Δ GAL-TEV/GAL-TEV ade2-n/ade2–I-SceI URA3-tetO112 LEU2-TetR-GFP | Petrini laboratory |

| JPY3166 | MATahta1-S129A hta2-S129A 3×HA-RAD9::URA3 hoΔ ade3::GAL::HO bar1::ADE3::bar1 hml1::ADE1 hmr::ADE1 | Petrini laboratory |

| JPY3653 | MATayku70Δ::KANMX6 | This study |

| JPY3663 | MATamre11-3::URA3 | This study |

| JPY3664 | MATα mre11-3::URA3 | This study |

| JPY4086 | MATα sae2Δ::KANMX6 yku70Δ::KANMX6 | This study |

| JPY4087 | MATamre11-3::URA3 yku70Δ::KANMX6 | This study |

| JPY4115 | MATα mre11-3::URA3 dnl4Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JPY4138 | MATα mre11-3::URA3 yku70Δ::KANMX6 | This study |

| JPY4139 | MATα yku70Δ::KANMX6 | This study |

| JPY4140 | MATamre11-3::URA3 yku70Δ::KANMX6 | This study |

| JPY4141 | mre11-3::URA3 | This study |

| JPY4142 | sgs1Δ::TRP1 yku70Δ::KANMX6 | This study |

| JPY4145 | mre11-3::URA3 sgs1Δ::TRP1 yku70Δ::KANMX6 | This study |

| JPY4150 | yku70Δ::KANMX6 | This study |

| JPY4243 | MATarad27::KANMX6 | This study |

| JPY4244 | MATamre11-3::URA3 | This study |

| JPY4245 | MATα sgs1Δ::TRP1 | This study |

| JPY4251 | MATamre11-3::URA3 sgs1Δ:TRP1 | This study |

| JPY4289 | MATamre11-3::URA3 bar1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JPY4290 | MATayku70Δ::KANMX6 bar1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JPY4291 | MATabar1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JPY4292 | MATayku70Δ::KANMX6 bar1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JPY4294 | MATamre11-3::URA3 yku70Δ::KANMX6 bar1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JPY4299 | MATα yku70Δ::KANMX6 exo1Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JPY4300 | MATamre11-3::URA3 exo1Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JPY4303 | MATα mre11-3::URA3 yku70Δ::KANMX6 exo1Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JPY4311 | MATamre11-3::URA3 sae2Δ::HYG yku70Δ::KANMX6 | This study |

| JPY4316 | MATamre11-3::URA3 sae2Δ::HYG | This study |

| JPY4318 | MATα mre11-3::URA3 yku70Δ::KANMX6 | |

| JPY4374 | MATatop1T722A-FLAG3::TRP1 bar1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JPY4417 | MATα mre11-3::URA3 yku70Δ::KANMX6 bar1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JPY4424 | MATamre11-3::URA3 yku70Δ::KANMX6 bar1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JPY4434 | MATα mre11-3::URA3 | This study |

| JPY4660b | MATa/MATα ade2-n/ade2–I-SceI | This study |

| JPY4662b | MATa/MATα ade2-n/ade2–I-SceI yku70Δ::KANMX6/yku70Δ::KANMX6 | This study |

| JPY4664b | MATa/MATα ade2-n/ade2–I-SceI mre11-3::URA3/mre11-3::URA3 | This study |

| JPY4665b | MATa/MATα ade2-n/ade2–I-SceI mre11-3::URA3/mre11-3::URA3 yku70Δ::KANMX6/yku70Δ::KANMX6 | This study |

| JPY5181 | MATamre11-3::URA3 bar1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JPY5184 | MATamre11-3::URA3 yku70Δ::KANMX6 bar1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JPY5195 | MATabar1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

Strains are in the W303 background (trp1-1 ura3-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 ade2-1 can1-100 RAD5).

Strains do not contain ade2-1.

DNA damage sensitivity analysis.

For spot tests, exponentially growing cultures at 30°C were serially diluted 5-fold and spotted onto solid 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose (YPD) medium containing the drug concentrations indicated on the figures and grown at 30°C for 1 to 2.5 days.

Determination of spore viability.

Diploids were sporulated in 1% potassium acetate, pH 7.0, for 3 days at 30°C. Spores were micromanipulated onto YPD medium and grown at 30°C for 3 to 6 days.

Cell cycle and Western blot analysis.

G1-arrested cultures at 2 × 107 cells/ml were split into the required number of smaller cultures and released at 30°C (25°C for flow cytometry) into YPD medium containing the drug doses indicated in the figure legends. For morphological cell cycle analysis, 5 × 106 cells were fixed at the time points indicated on the figures in 70% ethanol overnight at 4°C. Fixed cells were washed twice in water and sonicated, and the DNA was stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The percentage of large-budded mononucleated and binucleated cells was assessed as described previously (65). For analysis by flow cytometry, 1 × 106 fixed cells were incubated in 1 mg/ml RNase at 37°C overnight, followed by 5 mg/ml proteinase K treatment at 50°C for 60 min. Cells were washed once in water, briefly sonicated, resuspended in 10 μM SYTOX Green, and analyzed on a flow cytometer with 488-nm excitation. Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo. To prepare samples for Western blotting, protein was prepared from 2 × 107 cells by standard trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation. Samples were run on 15% gels and blotted with anti-H2A (phospho-S129A) (15083; Abcam), stripped, and blotted with anti-H2A (39689; Active Motif).

Heteroallelic recombination assay.

Diploids heterozygous for the ade2-n (20) and ade2–I-SceI (47) mutations were grown on YPD medium at 30°C for 4 days. Individual red colonies were diluted in sterile water and plated for single colonies on YPD medium containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 4 μM CPT. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 9 days, and the percentage of colonies containing one or more white sectors was determined. P values were calculated using a two-tailed Wilcoxon rank sum test (Mstat software [http://www.mcardle.wisc.edu/mstat/]).

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

G1-arrested cultures at 3 × 107 cells/ml were released at 25°C into either DMSO, 50 μM CPT, 0.035% MMS, or 20 μg/ml nocodazole. At the time points indicated on the figures, 1-ml samples were taken, and cell pellets were frozen until required. Agarose plug preparations and electrophoresis were carried out as previously described (36). The gels were stained with 1 μg/ml ethidium bromide overnight and visualized using UV transillumination. Quantitative densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ. For Southern blotting, DNA was transferred onto Hybond-XL membranes (GE Healthcare) by standard alkaline transfer and blotted with an ARS307 probe. Bands were visualized by a PhosphorImager (Fujifilm).

Band shift assay.

All DNA oligonucleotides were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) and PAGE purified before use. The oligonucleotides used to generate the dsDNA substrates with blunt ends (dsBE) (9) or 3′ overhangs (OH) (based on sequence from Burgreev and Mazin [6]) had the following sequences: dsBE-1, GGGTGAACCTGCAGGTGGGCAAAGATGTCCTAGCAATCCATTGGTGATCACTGGTAGCGG; dsBE-2, CCGCTACCAGTGATCACCAATGGATTGCTAGGACATCTTTGCCCACCTGCAGGTTCACCC; 3′ OH-1, ATCAGAGCAGATTGTACTGAGAGTGCACCATATGCGGTGTGAAATACCGCACAGATGCGT; 3′ OH-2, TGGTGCACTCTCAGTACAATCTGCTCTGATCGGCGTATCAATTCGGTCGGGGCTGTGGGC.

dsBE-1 and 3′ OH-1 were labeled at 5′ ends using T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB). Briefly, 10 pmol of DNA was incubated with 50 U of T4 kinase and 20 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP at 37°C for 1 h. Labeled DNA was purified through a QIAquick kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Equimolar amounts of complementary single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides were annealed in a buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and 5 mM MgCl2 at 95°C for 1 min, at 65°C for 10 min, at 37°C for 10 min, and at 22°C for 10 min in a PCR Thermocycler. Ku70-Ku80 purified complex (200 pmol) was incubated in the presence of 5′ labeled dsBE (50 fmol) and increasing amounts of unlabeled dsBE or 3′ OH as indicated in Fig. 6A. Binding reactions were carried out in 20 μl of gel retardation buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.8, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], and 10% glycerol). After incubation at 4°C for 30 min, reaction mixtures were loaded on a 5% neutral polyacrylamide gel prepared in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer. Gels were run in 0.5× TBE buffer at 70 V for 9 h at 4°C. Labeled DNA products were visualized in the dried gel by a PhosphorImager (Fujifilm) and quantified with the ImageGauge program.

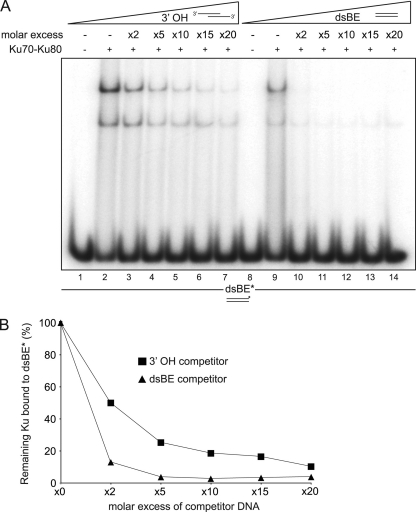

Fig. 6.

Ku preferentially binds blunt DNA ends over short ssDNA overhangs. (A) Ku70-Ku80 purified complex (200 pmol) was incubated with 50 fmol of 5′ labeled dsDNA (dsBE*, 60 bp of dsDNA with blunts ends) and increasing amounts of unlabeled dsBE DNA or a substrate containing 30 bp of dsDNA with 30-base 3′ overhangs (3′ OH). Lane numbers are indicated below the gel. (B) Quantification of gel in panel A. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

RESULTS

We previously showed that Ku deficiency mitigates the IR sensitivity of mre11Δ strains and that the suppressive effect was manifest primarily in S- and G2-phase cells (4). Based on these observations, we hypothesized that Ku and the Mre11 complex had antagonistic influences on HDR following IR. Loss of Ku has a similar effect on the MMS sensitivity of rad50Δ mutants in both budding and fission yeast (61, 68). In this study, given their opposing roles in DSB end resection (30, 42, 72), we examined the effect of yKu70 deficiency in mutants impaired for Mre11-dependent end processing upon challenge with an S phase-specific clastogen, CPT.

yku70Δ suppresses mre11-3 and sae2Δ DNA damage sensitivity.

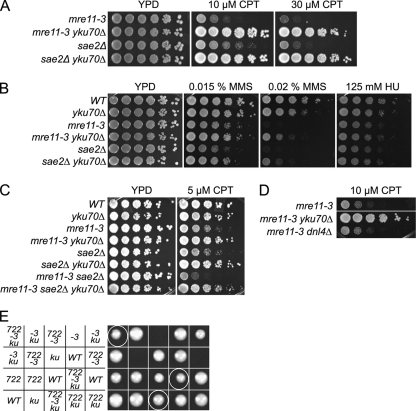

Ku-deficient strains harboring mre11-3 (nuclease dead) (5) or sae2Δ were established. Fivefold serially diluted cultures were plated onto solid medium containing CPT, MMS, or hydroxyurea (HU). mre11-3 and sae2Δ single mutants were sensitive to 10 μM CPT, whereas yKu70-deficient mre11-3 and sae2Δ mutants were resistant up to 30 μM CPT (Fig. 1A). The effect of Ku deficiency observed under conditions of chronic CPT exposure was recapitulated in response to acute treatment (data not shown). Similarly, yKu70 deficiency alleviated the sensitivity of mre11-3 and sae2Δ mutants to 0.015% and 0.02% MMS but conferred a minimal rescue of sensitivity to 125 mM HU (Fig. 1B). These data suggest that the basis of HU sensitivity in mre11-3 and sae2Δ mutants differs from that of CPT and MMS. Supporting this view, yKu70 deficiency did not alter the HU sensitivity of rad50Δ mutants but partially alleviated sensitivity to CPT and MMS (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

yKu70 deficiency alleviates the DNA damage sensitivity of mre11-3 and sae2Δ mutants. Growth of mre11-3 and sae2Δ mutants in the absence of yKu70 on CPT (A) and on MMS and HU (B). (C) Growth of sae2Δ mre11-3 mutant on CPT in the absence of yKu70. (D) CPT sensitivity of mre11-3 mutant in the absence of Dnl4. (E) Genetic interactions between top1-T722A (722), mre11-3 (-3) and yku70Δ (ku). Tetrads from a TOP1/top1-T722A MRE11/mre11-3 YKU70/yku70Δ sporulated diploid were dissected, and spore viability was assessed by growth.

That the CPT sensitivity of both mre11-3 and sae2Δ mutants is suppressed by yku70 deficiency suggests that the underlying basis of their respective CPT sensitivities is the same. However, mre11-3 sae2Δ double mutants exhibited higher CPT sensitivity than either single mutant (Fig. 1C), raising the possibility that they have nonredundant roles in responding to CPT-induced DNA damage. Nevertheless, deletion of YKU70 in mre11-3 sae2Δ mutants imparted CPT resistance to a similar degree as in either single mutant (Fig. 1C).

Recent reports demonstrate that mutations in DNA ligase IV and Ku mitigate the sensitivity of Fanconi anemia pathway mutants to DNA cross-linking agents, leading to the suggestion that NHEJ of DNA replication-associated lesions compromises cell viability (1, 51). This phenomenon does not underlie the rescue of CPT sensitivity in mre11-3 yku70Δ cells as DNA ligase IV deficiency in mre11-3 mutants did not alter CPT sensitivity at any dose tested (Fig. 1D and data not shown). These data indicate that yKu70 has an NHEJ-independent function that increases the toxicity of CPT-induced DNA lesions.

In the top1-T722A mutant, the half-life of the covalent Top1-DNA intermediate is increased, mimicking the effect of CPT (14, 39). Diploid strains harboring top1-T722A, mre11-3, and yku70Δ were generated, and spore viability was assessed. mre11-3 top1-T722A double mutant spores were largely inviable, whereas mre11-3 top1-T722A yku70Δ triple mutants did not exhibit strong growth defects (Fig. 1E). These data argue that Top1 defects, caused either by chemical or genetic inhibition, lead to the formation of DNA lesions that are substrates for the Mre11 nuclease and Sae2 as well as for yKu70 binding.

In S. cerevisiae, CPT treatment results in the accumulation of replication-dependent positive supercoiling in 2-μm circles in vivo (28). A similar accumulation of positive supercoiling may be exerted on the chromosomal level, potentially inhibiting replication fork progression. To address the possibility that this effect might partially underlie the CPT sensitivity, we expressed the catalytically active but CPT-resistant Top1-vac protein, which relieves positive supercoiling in yeast (27), in Mre11 nuclease- and Sae2-deficient mutants. Neither mre11-3 nor sae2Δ CPT sensitivity was altered by coexpression of endogenous S. cerevisiae Top1 and Top1-vac (data not shown), supporting the view that toxicity was primarily due to DSB induction.

Indices of DNA damage in CPT-treated mre11-3 cells.

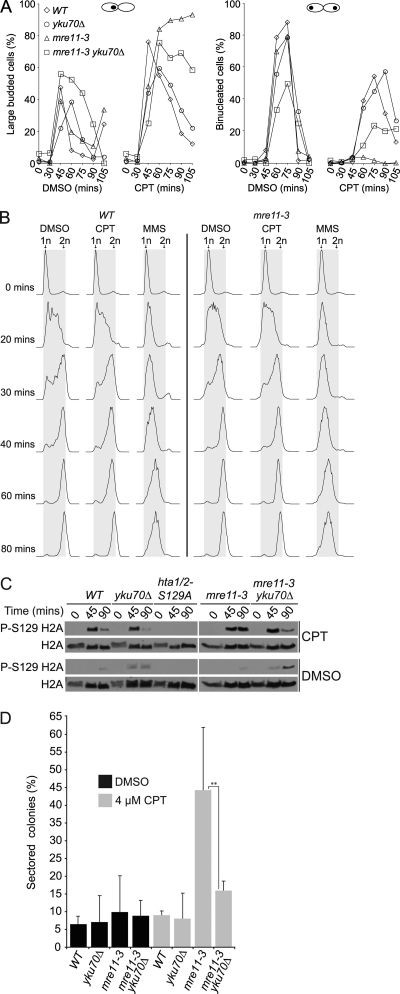

We tested the hypothesis that the yield of DSBs in CPT-treated mre11-3 cells was elevated using several criteria. First, cell cycle progression was assessed. G1-synchronized cultures were released into 40 μM CPT, and cell cycle position was assessed morphologically. A total of 93% of mre11-3 cells were scored as large-budded mononucleated cells, indicative of G2/M arrest, 105 min postrelease into CPT (Fig. 2A, second from left) and remained arrested up to 240 min (data not shown). This prolonged arrest was much less evident in the wild-type (WT), yku70Δ, or mre11-3 yku70Δ cells. In contrast to mre11-3, 55% of CPT-treated WT and 58% of yku70Δ cells were binucleated at by 75 and 90 min, respectively, whereas 24% of nuclei in mre11-3 yku70Δ mutants were divided at 75 min (Fig. 2A, far right).

Fig. 2.

CPT treatment induces G2/M arrest, γ-H2AX, and heteroallelic recombination in mre11-3 mutants. G1-arrested (0 min) cultures of the indicated strains were released into YPD medium containing DMSO, 40 μM CPT, or 0.035% MMS. (A) Cell cycle stage was determined by counting large-budded mononucleated (left-hand panels) and binucleated (right-hand panels) cells. (B) S-phase progression analyzed by flow cytometry. Experiments were each repeated three times. Representative data from single experiments are shown. (C) CPT-dependent γ-H2AX signal was determined in the indicated mutants by Western blotting. hta1/2-S129A indicates the H2A phosphorylation site mutant; P-S129 H2A indicates H2A-S129 phosphorylation. (D) Gene conversion in diploids heterozygous for the ade2-n and ade2–I-SceI mutations and harboring the indicated mutations. Heteroallelic recombination was assessed by determining the percentage of red colonies containing one or more white sectors. Data shown represent averages from four biological replicates. Error bars represent standard deviation (P = 0.0039).

Flow cytometric analysis indicated that CPT does not delay S phase and confirmed G2/M arrest in mre11-3 cells. It was previously shown that CPT does not induce a notable delay in replication in WT yeast cells (58). Similarly, DMSO- and CPT-treated WT and mre11-3 cells entered S phase by 20 min and contained diploid DNA content (2n) by 80 min (Fig. 2B). However, consistent with the morphological data, mre11-3 mutants remained arrested in G2/M up to 180 min post-G1 release (data not shown). In contrast, MMS-treated cells exhibited a notable delay within S phase (Fig. 2B), a response that has been shown to result from Mec1-dependent checkpoint activation (55). Given that both MMS and CPT are likely to induce DSBs, the lack of S-phase inhibition in response to CPT treatment may indicate that the checkpoint pathways do not sense the damage induced in mre11-3 cells until G2.

A second index of DSB induction was the formation of γ-H2AX. G1 cultures were released into 40 μM CPT, and γ-H2AX levels at time points following release were determined by Western blotting. As cells entered G2 (at 45 min, over 80% of cells in late-S/G2), γ-H2AX signal was detected in all strains (Fig. 2C). The γ-H2AX signal waned in WT, yku70Δ, and mre11-3 yku70Δ late-G2 cells (90 min), whereas in mre11-3 single mutants, signal persisted (Fig. 2C). These data confirm that CPT induces DSB accumulation as cells progress into G2, and these DSBs persist in mre11-3 cells, an outcome that is reduced in mre11-3 yku70Δ cells.

The third metric of DSB induction applied was the induction of DNA recombination. HDR-directed DSB repair exhibits a strong bias for using the sister chromatid as the repair template (23). We reasoned that if DSBs persisted in CPT-treated diploid mre11-3 cells, the frequency of inappropriate DSB repair from the homolog would be increased relative to WT cells in which DSBs did not persist. CPT-induced heteroallelic recombination was scored using diploid strains heterozygous for the ade2-n and ade2-I-SceI alleles. As a result of Ade2 deficiency, these strains grow as red colonies, and heteroallelic recombination leads to white sectoring (20).

Red colonies from WT, yku70Δ, mre11-3, and mre11-3 yku70Δ diploids heterozygous for the ade2 mutations were replated onto YPD plates containing either DMSO or 4 μM CPT. Induction of sectoring was negligible in WT and yku70Δ mutants. Growth on CPT increased the frequency of heteroallelic recombination in mre11-3 mutants 4.5-fold relative to DMSO-treated controls, whereas mre11-3 yku70Δ mutants exhibited only a 1.8-fold increase in CPT-induced recombination (Fig. 2D). A similar trend was observed at 2 μM CPT on synthetic complete medium (data not shown).

Finally, the effects of CPT were monitored by PFGE. With this technique, DSBs result in the diminution of full-length chromosome bands and the appearance of smears. In addition, replication intermediates are unable to enter the gel under the conditions used, providing a gross assessment of replication fork abundance at a given time point. Cells were released from G1 arrest into 50 μM CPT and harvested, and chromosomes were resolved by PFGE, with G1-arrested (n) and G2-arrested (2n) cultures serving as controls. At 25 min post-G1 release, the abundance of intact chromosomes in WT and mre11-3 cells was reduced irrespective of CPT treatment (Fig. 3A, lanes 3, 5, 10, and 12), consistent with the bulk of the cultures entering S phase (Fig. 3B). By 75 min, chromosome band intensities in DMSO-treated cultures approximated those of nocodazole-arrested G2 cells (Fig. 3A, lanes 2, 4, and 11). Chromosome band intensities in CPT-treated cultures did not recover by 75 min. The single band attributable to chromosomes VII and XV exhibited approximately 63% and 31% of the signal intensity relative to the corresponding DMSO band in WT and mre11-3 cells, respectively (Fig. 3A, lanes 4, 6, 11, and 13). However, by 90 min, chromosome band intensities were similar between DMSO- and CPT-treated WT G2 cultures (data not shown). In contrast, the intensity of chromosomal bands in CPT-treated mre11-3 cells did not recover to the level of G2 cells, and extensive smearing was evident (Fig. 3A, lane 6, and C, lanes 6 and 7). The smearing observed was markedly reduced in mre11-3 yku70Δ cells (Fig. 3C, lanes 13 and 14), and band intensities were indistinguishable between DMSO- and CPT-treated cultures (Fig. 3C, lanes 11 and 14).

Fig. 3.

CPT induces chromosome breakage in mre11-3 mutants. Chromosome integrity was monitored by PFGE analysis. (A) Analysis of WT and mre11-3 cells. G1-arrested cells were released into DMSO (D), 50 μM CPT (C), or 0.035% MMS (M). Numbers above the gel indicate time (in min) post-G1 release; P indicates plug; lane numbers appear below the gel. G1 (alpha-factor arrested) and G2 (nocodazole arrested) cells indicate 1n and 2n DNA controls, respectively. The ethidium bromide-stained gel was visualized using UV transillumination. A single representative gel is shown. Observations were confirmed with independent strains. (B) Cell cycle analysis of samples used in panel A. (C) Analysis of mre11-3 and mre11-3 yku70Δ cultures. (D) Cell cycle analysis of samples used in panel C.

Unlike CPT treatment, MMS caused the accumulation of cells in S phase (Fig. 3B), with virtually all of the chromosomes blocked from entering the gel by 75 min (Fig. 3A, lanes 8 and 15). Nevertheless, the possibility that CPT-treated mre11-3 cells had blocked replication intermediates in addition to DSBs was addressed. Southern blotting with a probe specific to chromosome III was carried out to detect persistent non-DSB complex DNA structures in CPT-arrested mre11-3 cells, which we reasoned would remain in the plug or migrate more slowly. The data obtained were consistent with the presence of lower-molecular-weight DNA, and the presence of aberrant DNA structures was not indicated in mre11-3 samples (data not shown). DSB formation, as inferred from PFGE, was not dependent upon Mus81 as mre11-3 mus81Δ mutants were indistinguishable from mre11-3 cells in that experimental setting (data not shown). Collectively, these data support the view that CPT induces DSBs in mre11-3 mutants although we cannot exclude the possibility that non-DSB structures also contribute to the phenotypes observed.

Exo1 is required for yku70Δ-dependent suppression of CPT sensitivity.

Given that yKu70 deficiency increases ssDNA generation at HO-induced DSBs and telomeres (30, 35), we hypothesized the yku70Δ-mediated rescue of Mre11 nuclease deficiency was attributable to increased resection of DSBs leading to the generation of substrates suitable for HDR. To test this, we assessed the requirement of Exo1 and Sgs1 in yku70Δ-dependent CPT resistance.

We found that Exo1 deficiency abolished yku70Δ-dependent suppression of mre11-3 CPT sensitivity (Fig. 4A). mre11-3 exo1Δ yku70Δ triple mutants exhibited a higher CPT sensitivity than either mre11-3 yku70Δ or mre11-3 cells. In addition, Exo1 deficiency partially increased the CPT sensitivity of both mre11-3 and yku70Δ single mutants, supporting the view that DNA end resection by Exo1 is the basis of the yku70Δ rescue (Fig. 4A). A similar phenotype was observed in fission yeast (69). These data are consistent with the view that Ku inhibits the ability of Exo1 to act at DSB ends.

Fig. 4.

The yku70Δ-dependent rescue of mre11-3 CPT sensitivity requires EXO1. CPT sensitivity of mre11-3 yku70Δ mutants in the absence of Exo1 (A) and Sgs1 (B).

Like Exo1, Sgs1 functions in the later stages of DSB resection (17, 42, 72); however, deletion of Sgs1 did not phenocopy exo1Δ. mre11-3 sgs1Δ and yku70Δ sgs1Δ cells exhibited sharply increased CPT sensitivity relative to mre11-3 and yku70Δ cells, respectively (Fig. 4B). Deletion of Ku to create mre11-3 sgs1Δ yku70Δ triple mutants increased CPT resistance relative to mre11-3 sgs1Δ double mutants, approximately to the level of sgs1Δ yku70Δ at 2 μM and 10 μM CPT. Given its antirecombinogenic role (16, 22), the CPT hypersensitivity of mre11-3 sgs1Δ and yku70Δ sgs1Δ mutants may be attributable to the accumulation of CPT-induced toxic recombination intermediates. Alternatively, the synergistic CPT sensitivity of mre11-3 sgs1Δ mutants may reflect additivity of their resection defects.

mre11-3 rad27Δ synthetic lethality is suppressed by yKu70 deficiency.

Nuclease-deficient mre11 mutants are synthetically lethal with rad27Δ (10, 45). rad27Δ strains exhibit a dramatic increase in gross chromosomal rearrangements (8), indicating that spontaneous chromosome breakage is elevated in those cells, presumably as a result of replication fork breakage. To test the hypothesis that synthetic lethality is attributable to defects in the repair of replication associated DSBs, MRE11/mre11-3 RAD27/rad27Δ YKU70/yku70Δ diploids were sporulated, and viability was assessed. As expected, all mre11-3 rad27Δ double mutants were inviable, but in the context of yKu70 deficiency, 14 out of 17 mre11-3 rad27Δ yku70Δ spores grew into a visible colony (Fig. 5). Spore viability in this context was not due to perdurance of the proteins from the heterozygous parents, as restreaks of the triple mutants remain viable (data not shown). Similarly, yKu70 deficiency was recently shown to alleviate the growth defect in sae2Δ rad27Δ mutants (41). These data support the interpretation that the mre11-3 rad27Δ synthetic lethality is attributable to the accumulation of a toxic DNA structure that would otherwise be engaged by Ku. Given that Exo1 overexpression also suppresses this synthetic lethality, a parsimonious interpretation would be that the toxic structure in question is a DSB. As with CPT-associated DSBs, suppression of this mre11-3 phenotype by yKu70 deficiency reflects an S-phase-specific, NHEJ-independent function of the Ku heterodimer.

Fig. 5.

yKu70 deficiency alleviates the mre11-3 rad27Δ synthetic lethality. Genetic interactions between mre11-3 (-3), rad27Δ (27), and yku70Δ (ku). Tetrads from an MRE11/mre11-3 RAD27/rad27Δ yku70Δ/YKU70 sporulated diploid were dissected, and spore viability was assessed by growth.

Ku binds poorly to ssDNA overhangs.

The data presented thus far indicated that yKu70 inhibited DSB repair in the absence of the Mre11 nuclease and Sae2 and led us to suggest that the generation of short ssDNA overhangs by the Mre11 nuclease and Sae2 is required to inhibit Ku binding at DSB ends, thereby priming ends for Exo1-dependent long-range resection and HDR. Alternatively, given its high affinity for DNA ends, Ku may rapidly bind at DSBs prior to end processing by Mre11/Sae2. This scenario would suggest that the Mre11 nuclease and Sae2 endonucleolytically clip DSBs to remove already bound Ku.

We tested the ability of Ku to bind ssDNA overhang ends analogous to those generated by Mre11/Sae2 using electrophoretic mobility shift assays. Incubation of Ku complex with a radioactively labeled 60-bp blunt-ended dsDNA substrate produced slowly migrating species (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 and 9), reflecting Ku's previously established DNA end binding function (3, 53). Addition of cold blunt-ended DNA prior to binding markedly reduced the abundance of the shifted species (Fig. 6A, lanes 10 to 14), resulting in a 27-fold decrease of labeled Ku-DNA complex when present at five times molar excess (Fig. 6B). In contrast, a five times molar excess of unlabeled duplex DNA containing 30-base overhangs diminished the shifted product by only 4-fold (Fig. 6A, lanes 3 to 7, and B). These data demonstrate that, relative to blunt ends, Ku binds poorly to DNA ends containing ssDNA overhangs, supporting the hypothesis that Mre11 nuclease- and Sae2-dependent processing of DSBs in vivo discourages engagement by the Ku heterodimer and promotes DSB resection.

DISCUSSION

In this study we investigated the interplay of Mre11 and Sae2, both required for early steps in the processing of DNA ends prior to DNA repair, and the DNA end binding factor yKu70. The data herein demonstrate a critical role for Mre11 nuclease activity in the repair of replication-dependent DSBs and highlight an NHEJ-independent role for yKu70 in antagonizing DSB repair in S phase and G2.

We show that Mre11 nuclease activity and Sae2 are largely dispensable for cell viability in yKu70-deficient cells while the requirement for Exo1 remains. On this basis, we propose that Ku binds to and excludes Exo1 from processing DNA structures that are formed in response to CPT-induced genotoxic stress. Given that Mre11 and Sae2 act upstream of Exo1 in DSB end resection (42, 72), we propose that initial endonucleolytic cleavage events are catalyzed by the Mre11 nuclease and Sae2 and serve to inhibit Ku binding, thereby potentiating Exo1-mediated resection and promoting HDR-dependent repair.

The model proposed above posits that Ku deficiency facilitates the resolution of toxic DNA adducts stabilized by Mre11 nuclease and Sae2 deficiency. Implicitly, this hypothesis requires that the DNA structures to which Ku binds are normally processed by the Mre11 nuclease and Sae2 and are thus more abundant in Mre11 nuclease- and Sae2-deficient cells.

Several lines of evidence support the view that these toxic DNA structures are DSBs. First, Ku exhibits a strong preference for binding to dsDNA ends over ssDNA or circular DNA (12, 43, 53). Second, CPT-induced cell cycle arrest, γ-H2AX signal, heteroallelic recombination, and chromosome breakage were all enhanced in mre11-3 cells and reduced to essentially wild-type levels in mre11-3 yku70Δ double mutant cells (Fig. 2 and 3). These endpoints are each sensitive indices of DSB abundance and support the interpretation that yKu70 antagonizes HDR-mediated DSB repair in S phase and G2 in the absence of Mre11 nuclease activity. The function of Ku in this regard is not simply to promote NHEJ over HDR as inactivating NHEJ via a DNA ligase IV deficiency had no effect on mre11-3 CPT sensitivity (Fig. 1D). These and other data support the view that DSB end binding by the Ku heterodimer influences mitotic DNA repair by limiting access of Exo1 for resection.

We propose that a role of the initial cleavage step at mitotic DSB ends by the Mre11 nuclease and Sae2 is to counterbalance this NHEJ-independent Ku function though the precise interaction between Mre11 and Sae2 during end processing remains unclear. In light of their role in this mechanism, the clastogen sensitivities observed in Mre11 nuclease and Sae2 deficiency are likely attributable to defects in HDR-mediated DNA repair. In this model, the initial Mre11 nuclease/Sae2-dependent cleavage step would inhibit or dismantle Ku binding at DSB ends and thereby promote resection by Exo1. Consistent with this view, Ku has a significantly higher affinity for blunt dsDNA ends over short ssDNA overhangs (Fig. 6). Accordingly, Ku deficiency effectively bypasses the need for the initial incision step and permits Exo1 to effect resection in mre11-3 and sae2Δ mutants. In further support of this idea, Ku deficiency was recently shown to alleviate the resection defect at an HO-induced DSB in rad50Δ and sae2Δ mutants (41, 60). On the other hand, mre11-3 and sae2Δ mutants, unlike mre11Δ cells, did not exhibit higher detectable levels of Ku bound at an HO-induced DSB when measured by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) (60, 71). This discrepancy may be attributable to differential processing requirements of HO- and CPT-induced DNA ends and additionally due to the S-phase specificity of CPT-induced lesions.

We consider two nonexclusive possibilities for the molecular basis of increased DSBs in CPT-treated mre11-3 mutants: defects in the resolution of topoisomerase adducts and defects in DSB repair. Several lines of evidence support the view that both the Mre11 complex and Sae2 promote the resolution of Top1-DNA cleavage complexes. Impaired resolution would increase the stability of adducts and accordingly increase the risk of collision with the replisome. Increased levels of Top1-DNA adducts have been detected in Schizosaccharomyces pombe rad32mre11-D65N nuclease and rad50S mutants (18), and S. cerevisiae mre11 and sae2Δ mutants and murine Rad50S/S cells are CPT sensitive (Fig. 1A) (11, 44). It is conceivable that the Ku heterodimer may bind to Top1-associated DSB ends. However, the flap endonuclease activity of Exo1 is the incorrect polarity to remove the Top1-associated ends (62). Hence, this could not account for the suppression of CPT sensitivity by yKu70 deficiency in mre11-3 and sae2Δ cells.

An alternative scenario is that the leading strand encounters the 5′ OH side of the nick created by the cleavage complex, leading to polymerase runoff and ultimately a single-ended DSB (57). These DSB ends would likely be substrates for Mre11 and Sae2, as well as Ku binding. These DSBs would accumulate in mre11-3 cells in a Ku-dependent, Mus81-independent manner and are possibly the basis of the mre11-3 CPT toxicity (Fig. 7). In this scenario, the Exo1-dependent suppression of mre11-3 CPT sensitivity by yku70Δ would reflect the promotion of DSB resection en route to HDR-mediated repair (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Antagonistic roles for Ku and Mre11 in S-phase DSB metabolism. We propose that the resection of DNA replication-associated DSBs is regulated negatively by the Ku heterodimer and positively by Mre11 nuclease- or Sae2-dependent activities. In this figure, DSBs associated with CPT lesions are depicted on the left, and those associated with fork breakage in rad27Δ are shown on the right. In both cases, the action of Mre11 or Sae2 ultimately promotes resection, potentiating HDR of the DSB.

Finally, a competitive relationship between Ku and the Mre11 complex has been suggested to provide a mechanism of DSB processing and repair pathway choice (41, 60, 61, 71). Limited resection in G1 cells promotes Ku- and DNA ligase IV-dependent NHEJ, whereas increased cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity leads to increased resection and promotion of HDR (40). However, the data presented herein clearly demonstrate a previously uncharacterized role for Ku in mediating DSB repair during DNA replication and the subsequent G2. The S/G2 functions of Ku are independent of NHEJ and suggest that the heterodimer exerts a relatively broad regulatory influence on the metabolism of toxic DNA structures formed in the course of DNA replication.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lorraine Symington for the ade2-n and ade2–I-SceI mutants, Alain Verreault for pRS-TOP1-FLAG3 vectors, Mary-Ann Bjornsti for YCp-ScTop1 vectors, Xiaolan Zhao for the mus81Δ mutant and advice, Alan Tomkinson for Ku protein, Marco Muzi-Falconi for anti-Rad53, Stewart Shuman for advice, and Marcel Hohl and other members of our laboratory for insightful discussion. We are particularly indebted to Massimo Lopes and Arnab Ray Chaudhuri for advice on this study.

This work was supported by the American Italian Cancer Foundation (A.B.) and NIH grants to J.H.J.P.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 August 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adamo A., et al. 2010. Preventing nonhomologous end joining suppresses DNA repair defects of Fanconi anemia. Mol. Cell 39:25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arosio D., et al. 2002. Studies on the mode of Ku interaction with DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 277:9741–9748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bianchi A., de Lange T. 1999. Ku binds telomeric DNA in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 274:21223–21227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bressan D. A., Baxter B. K., Petrini J. H. 1999. The Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 protein complex facilitates homologous recombination-based double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:7681–7687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bressan D. A., Olivares H. A., Nelms B. E., Petrini J. H. 1998. Alteration of N-terminal phosphoesterase signature motifs inactivates Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11. Genetics 150:591–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bugreev D. V., Mazin A. V. 2004. Ca2+ activates human homologous recombination protein Rad51 by modulating its ATPase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:9988–9993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cejka P., et al. 2010. DNA end resection by Dna2-Sgs1-RPA and its stimulation by Top3-Rmi1 and Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2. Nature 467:112–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen C., Kolodner R. D. 1999. Gross chromosomal rearrangements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae replication and recombination defective mutants. Nat. Genet. 23:81–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ciccia A., et al. 2007. Identification of FAAP24, a Fanconi anemia core complex protein that interacts with FANCM. Mol. Cell 25:331–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Debrauwere H., Loeillet S., Lin W., Lopes J., Nicolas A. 2001. Links between replication and recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a hypersensitive requirement for homologous recombination in the absence of Rad27 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:8263–8269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deng C., Brown J. A., You D., Brown J. M. 2005. Multiple endonucleases function to repair covalent topoisomerase I complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 170:591–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dynan W. S., Yoo S. 1998. Interaction of Ku protein and DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit with nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:1551–1559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feldmann H., Winnacker E. L. 1993. A putative homologue of the human autoantigen Ku from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 268:12895–12900 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fiorani P., Bjornsti M. A. 2000. Mechanisms of DNA topoisomerase I-induced cell killing in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 922:65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Furuta T., et al. 2003. Phosphorylation of histone H2AX and activation of Mre11, Rad50, and Nbs1 in response to replication-dependent DNA double-strand breaks induced by mammalian DNA topoisomerase I cleavage complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 278:20303–20312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gangloff S., Soustelle C., Fabre F. 2000. Homologous recombination is responsible for cell death in the absence of the Sgs1 and Srs2 helicases. Nat. Genet. 25:192–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gravel S., Chapman J. R., Magill C., Jackson S. P. 2008. DNA helicases Sgs1 and BLM promote DNA double-strand break resection. Genes Dev. 22:2767–2772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hartsuiker E., Neale M. J., Carr A. M. 2009. Distinct requirements for the Rad32(Mre11) nuclease and Ctp1(CtIP) in the removal of covalently bound topoisomerase I and II from DNA. Mol. Cell 33:117–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hsiang Y. H., Lihou M. G., Liu L. F. 1989. Arrest of replication forks by drug-stabilized topoisomerase I-DNA cleavable complexes as a mechanism of cell killing by camptothecin. Cancer Res. 49:5077–5082 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huang K. N., Symington L. S. 1994. Mutation of the gene encoding protein kinase C 1 stimulates mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:6039–6045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huertas P., Cortes-Ledesma F., Sartori A. A., Aguilera A., Jackson S. P. 2008. CDK targets Sae2 to control DNA-end resection and homologous recombination. Nature 455:689–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ira G., Malkova A., Liberi G., Foiani M., Haber J. E. 2003. Srs2 and Sgs1-Top3 suppress crossovers during double-strand break repair in yeast. Cell 115:401–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kadyk L. C., Hartwell L. H. 1992. Sister chromatids are preferred over homologs as substrates for recombinational repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 132:387–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Keeney S., Giroux C. N., Kleckner N. 1997. Meiosis-specific DNA double-strand breaks are catalyzed by Spo11, a member of a widely conserved protein family. Cell 88:375–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Keeney S., Kleckner N. 1995. Covalent protein-DNA complexes at the 5′ strand termini of meiosis-specific double-strand breaks in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:11274–11278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim H. S., et al. 2008. Functional interactions between Sae2 and the Mre11 complex. Genetics 178:711–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Knab A. M., Fertala J., Bjornsti M. A. 1993. Mechanisms of camptothecin resistance in yeast DNA topoisomerase I mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 268:22322–22330 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koster D. A., Palle K., Bot E. S., Bjornsti M. A., Dekker N. H. 2007. Antitumour drugs impede DNA uncoiling by topoisomerase I. Nature 448:213–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee S. E., Bressan D. A., Petrini J. H., Haber J. E. 2002. Complementation between N-terminal Saccharomyces cerevisiae mre11 alleles in DNA repair and telomere length maintenance. DNA Repair (Amst.) 1:27–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee S. E., et al. 1998. Saccharomyces Ku70, Mre11/Rad50, and RPA proteins regulate adaptation to G2/M arrest after DNA damage. Cell 94:399–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lengsfeld B. M., Rattray A. J., Bhaskara V., Ghirlando R., Paull T. T. 2007. Sae2 is an endonuclease that processes hairpin DNA cooperatively with the Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 complex. Mol. Cell 28:638–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu C., Pouliot J. J., Nash H. A. 2002. Repair of topoisomerase I covalent complexes in the absence of the tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase Tdp1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99:14970–14975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lobachev K. S., Gordenin D. A., Resnick M. A. 2002. The Mre11 complex is required for repair of hairpin-capped double-strand breaks and prevention of chromosome rearrangements. Cell 108:183–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Longtine M. S., et al. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maringele L., Lydall D. 2002. EXO1-dependent single-stranded DNA at telomeres activates subsets of DNA damage and spindle checkpoint pathways in budding yeast yku70Δ mutants. Genes Dev. 16:1919–1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maringele L., Lydall D. 2006. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of budding yeast chromosomes. Methods Mol. Biol. 313:65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Masumoto H., Hawke D., Kobayashi R., Verreault A. 2005. A role for cell-cycle-regulated histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation in the DNA damage response. Nature 436:294–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McKee A. H., Kleckner N. 1997. A general method for identifying recessive diploid-specific mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, its application to the isolation of mutants blocked at intermediate stages of meiotic prophase and characterization of a new gene SAE2. Genetics 146:797–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Megonigal M. D., Fertala J., Bjornsti M. A. 1997. Alterations in the catalytic activity of yeast DNA topoisomerase I result in cell cycle arrest and cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 272:12801–12808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mimitou E. P., Symington L. S. 2009. DNA end resection: many nucleases make light work. DNA Repair (Amst.) 8:983–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mimitou E. P., Symington L. S. 2010. Ku prevents Exo1 and Sgs1-dependent resection of DNA ends in the absence of a functional MRX complex or Sae2. EMBO J. 29:3358–3369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mimitou E. P., Symington L. S. 2008. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature 455:770–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mimori T., Hardin J. A. 1986. Mechanism of interaction between Ku protein and DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 261:10375–10379 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Morales M., et al. 2008. DNA damage signaling in hematopoietic cells: a role for Mre11 complex repair of topoisomerase lesions. Cancer Res. 68:2186–2193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Moreau S., Ferguson J. R., Symington L. S. 1999. The nuclease activity of Mre11 Is required for meiosis but not for mating type switching, end joining, or telomere maintenance. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:556–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Moreau S., Morgan E. A., Symington L. S. 2001. Overlapping Functions of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11, Exo1 and Rad27 Nucleases in DNA Metabolism. Genetics 159:1423–1433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mozlin A. M., Fung C. W., Symington L. S. 2008. Role of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad51 paralogs in sister chromatid recombination. Genetics 178:113–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Neale M. J., Pan J., Keeney S. 2005. Endonucleolytic processing of covalent protein-linked DNA double-strand breaks. Nature 436:1053–1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nicolette M. L., et al. 2010. Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 and Sae2 promote 5′ strand resection of DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17:1478–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Niu H., et al. 2010. Mechanism of the ATP-dependent DNA end-resection machinery from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 467:108–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pace P., et al. 2010. Ku70 corrupts DNA repair in the absence of the Fanconi anemia pathway. Science 329:219–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Paillard S., Strauss F. 1991. Analysis of the mechanism of interaction of simian Ku protein with DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:5619–5624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pang D., Yoo S., Dynan W. S., Jung M., Dritschilo A. 1997. Ku proteins join DNA fragments as shown by atomic force microscopy. Cancer Res. 57:1412–1415 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Paull T. T., Gellert M. 1998. The 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity of Mre 11 facilitates repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Mol. Cell 1:969–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Paulovich A. G., Hartwell L. H. 1995. A checkpoint regulates the rate of progression through S phase in S. cerevisiae in response to DNA damage. Cell 82:841–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pommier Y. 2006. Topoisomerase I inhibitors: camptothecins and beyond. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 6:789–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pommier Y., et al. 2006. Repair of topoisomerase I-mediated DNA damage. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 81:179–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Redon C., et al. 2003. Yeast histone 2A serine 129 is essential for the efficient repair of checkpoint-blind DNA damage. EMBO Rep. 4:678–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Seiler J. A., Conti C., Syed A., Aladjem M. I., Pommier Y. 2007. The intra-S-phase checkpoint affects both DNA replication initiation and elongation: single-cell and -DNA fiber analyses. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:5806–5818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Shim E. Y., et al. 2010. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 and Ku proteins regulate association of Exo1 and Dna2 with DNA breaks. EMBO J. 29:3370–3380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tomita K., et al. 2003. Competition between the Rad50 complex and the Ku heterodimer reveals a role for Exo1 in processing double-strand breaks but not telomeres. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:5186–5197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tran P. T., Erdeniz N., Dudley S., Liskay R. M. 2002. Characterization of nuclease-dependent functions of Exo1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair (Amst.) 1:895–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Trujillo K. M., Sung P. 2001. DNA structure-specific nuclease activities in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad50*Mre11 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 276:35458–35464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Trujillo K. M., Yuan S.-S., Lee E. Y., Sung P. 1998. Nuclease activities in a complex of human recombination and DNA repair factors Rad50, Mre11, and p95. J. Biol. Chem. 273:21447–21450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Usui T., Ogawa H., Petrini J. H. 2001. A DNA damage response pathway controlled by Tel1 and the Mre11 complex. Mol. Cell 7:1255–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Usui T., et al. 1998. Complex formation and functional versatility of Mre11 of budding yeast in recombination. Cell 95:705–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Vance J. R., Wilson T. E. 2002. Yeast Tdp1 and Rad1-Rad10 function as redundant pathways for repairing Top1 replicative damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:13669–13674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wasko B. M., Holland C. L., Resnick M. A., Lewis L. K. 2009. Inhibition of DNA double-strand break repair by the Ku heterodimer in mrx mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair (Amst.) 8:162–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Williams R. S., et al. 2008. Mre11 dimers coordinate DNA end bridging and nuclease processing in double-strand-break repair. Cell 135:97–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yu J., Marshall K., Yamaguchi M., Haber J. E., Weil C. F. 2004. Microhomology-dependent end joining and repair of transposon-induced DNA hairpins by host factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:1351–1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhang Y., et al. 2007. Role of Dnl4-Lif1 in nonhomologous end-joining repair complex assembly and suppression of homologous recombination. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14:639–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhu Z., Chung W. H., Shim E. Y., Lee S. E., Ira G. 2008. Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell 134:981–994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]