Abstract

The TAR RNA binding protein, TRBP, is a cellular double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) binding protein that can promote the replication of HIV-1 through interactions with the viral TAR element as well as with cellular proteins that affect the efficiency of translation of viral transcripts. The structured TAR element, present on all viral transcripts, can impede efficient translation either by sterically blocking access of translation initiation factors to the 5′-cap or by activating the dsRNA-dependent kinase, PKR. Several mechanisms by which TRBP can facilitate translation of viral transcripts have been proposed, including the binding and unwinding of TAR and the suppression of PKR activation. Further, TRBP has been identified as a cofactor of Dicer in the processing of microRNAs (miRNAs), and sequestration of TRBP by TAR in infected cells has been proposed as a viral countermeasure to potential host cell RNA interference-based antiviral activities. Here, we have addressed the relative importance of these various roles for TRBP in HIV-1 replication. Using Jurkat T cells, primary human CD4+ T cells, and additional cultured cell lines, we show that depletion of TRBP has no effect on viral replication when PKR activation is otherwise blocked. Moreover, the presence of TAR-containing mRNAs does not affect the efficacy of cellular miRNA silencing pathways. These results establish that TRBP, when expressed at physiological levels, promotes HIV-1 replication mainly by suppressing the PKR-mediated antiviral response, while its contribution to HIV-1 replication through PKR-independent pathways is minimal.

INTRODUCTION

The TAR (transactivation response) RNA binding protein, TRBP, is a cellular double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) binding protein that has been shown to promote the replication of human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 (HIV-1 and -2) (9, 22). TRBP was originally isolated on the basis of its high-affinity binding to the 59-nucleotide (nt) conserved and structured TAR element found at the 5′ and 3′ ends of all HIV-1 transcripts (21), and it has subsequently been identified as a cofactor for the cellular RNase III enzyme, Dicer, in the microRNA (miRNA) processing pathway (8, 28). Initially it was suggested that TRBP, when recruited to TAR, could facilitate HIV-1 replication by acting synergistically with the viral protein Tat to increase long terminal repeat (LTR) transcriptional transactivation (21). Since then, however, studies have pointed to a predominantly posttranscriptional role for TRBP, and it is now thought to act to relieve TAR-related barriers to translation of viral transcripts. For instance, the bulged stem-loop structure of TAR at the very 5′ end of mRNAs can serve to block accessibility of the 5′-methylated guanosine cap to factors necessary for translation initiation (23, 44). TAR has also been reported to bind and activate the dsRNA-dependent protein kinase, PKR, resulting in phosphorylation of the α-subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2α), with subsequent inhibition of translation (6, 29, 31, 39). TRBP can alleviate these translational blocks by binding and unwinding the TAR structure, increasing access to the 5′ cap and enhancing cap-dependent translational initiation (16), or by binding to TAR and competitively inhibiting the binding and activation of PKR (43). TRBP has also been shown to interact directly with PKR in an RNA-independent manner to suppress its activation (2, 13).

In addition to promoting the translation of TAR-containing viral transcripts, TRBP has been suggested to affect HIV-1 replication through its role in RNA interference (RNAi). TRBP is a binding partner of Dicer and a component of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), and reductions in the level of TRBP lead to lower efficacy of RNA silencing (8, 28). It has been proposed that TRBP can be sequestered by binding to TAR in HIV-1-infected cells, leading to a global suppression of RNAi and serving as a viral strategy to defeat cellular RNAi-based antiviral defenses (3, 22). However, the importance of viral suppression of RNAi in providing an environment that will support robust viral replication remains controversial (38, 48).

It is evident that TRBP can contribute to the efficiency of HIV-1 gene expression, and it has been proposed as a cellular target for antiviral therapies (9, 17). However, it is still unclear which of several potential mechanisms of action is most important in mediating the effects of TRBP when it is expressed at physiological levels and in cells that serve as natural hosts for HIV-1 infection. Here, we have examined the extent to which TRBP can regulate HIV-1 replication through its ability to inhibit PKR, unwind TAR, or contribute to RNA silencing, under conditions where it is not overexpressed and in T cell lines that support HIV-1 infection and replication. Additionally, we have assessed the ability of TRBP to promote HIV-1 replication in primary CD4+ T cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and plasmids.

P4R5-MAGI cells (32) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), sodium bicarbonate (0.05%), antibiotics (penicillin, streptomycin, and kanamycin at 40 μg/ml each), and puromycin (1 μg/ml). The growth medium for HeLa cells was the same as for P4R5 cells but without puromycin. HEK-293T cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. Jurkat cells were grown in RPMI supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, antibiotics (penicillin, streptomycin, and kanamycin at 40 μg/ml each), 4.5 g/liter glucose, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 10 mM HEPES. Primary CD4+ T cells were separated by negative selection from total peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from healthy donors and were obtained from the University of Pennsylvania Cell Center. They were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, antibiotics (penicillin, streptomycin, and kanamycin at 40 μg/ml each), and interleukin-2 (IL-2; 20 U/ml). When indicated, T cells were activated by treatment with phytohemagglutinin (PHA; 1 μg/ml) for 3 days.

Plasmid carrying a dominant negative inhibitor of PKR, pPKR-Δ6, was a kind gift from Thomas Dever (NIH). The LAI TAR element used to construct pCMV-TAR-Rluc (pTAR-Rluc) was assembled by annealing complementary oligonucleotides (47) and then inserted between a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and Renilla luciferase coding sequence. pCMV-Rluc (pRluc) was similar but contained no TAR element. The TRBP expression plasmid was constructed by inserting TRBP cDNA from the Open Biosystems clone 2960701 between AflII and NotI restriction sites in pcDNA3.1/hygro (Invitrogen). All plasmid constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Nonspecific and three TRBP-specific small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) used in this study were obtained from Sigma (nonspecific [NS] siRNA [SIC001], siTRBP-1 [SASI_Hs01_00171749], siTRBP-2 [SASI_Hs01_00171750], and siTRBP-3 [SASI_Hs01_00171751]), while siPKR was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-36263). The efficacy of siPKR in knocking down PKR was confirmed by immunoblot analysis of transfected 293T cells (data not shown). In experiments testing the effects of siTRBP, with and without the addition of siPKR, the total amount of siRNA added was kept constant by the addition of NS siRNA to cells receiving siTRBP without siPKR.

Transfections and P4R5 infection assays.

HeLa cells were transfected with GenDrill transfection reagent (BamaGen) and following the manufacturer's instructions. A calcium phosphate precipitation procedure was used to transfect HEK-293T cells, while Trans-IT Jurkat (Mirus) was used to transfect Jurkat cells following the manufacturer's instructions. Primary T cells were transfected by using the Amaxa human primary T cell transfection kit following the manufacturer's protocol. For infection, primary cells were harvested 24 h after siRNA transfection and infected for 4 h in 200 μl viral supernatant containing HIV-1 LAI (4 ng p24) and 8 μg/ml Polybrene. After infection, cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated for a further 24 h in fresh medium. P4R5 infection assays were performed as described previously (47).

Immunoblot assays.

Cell extracts for immunoblotting were prepared by lysis in 0.5 × radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer supplemented with Complete protease inhibitor (Roche), phosphatase inhibitor cocktails I and II (Sigma), and the kinase inhibitor 2-aminopurine (10 mM). Following treatment with benzonase nuclease (Sigma), 20 to 50 μg total protein was size fractionated on a 12% PAGE–SDS gel and electrotransferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon). Primary antibodies used in this study were anti-enhanced GFP (anti-EGFP; Chemicon), anti-actin, anti-total eIF2α, anti-PKR (Santa Cruz), anti-phosphoryated eIF2α (anti-P-eIF2α; BioSource), and anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH; GenScript). The polyclonal antibody against TRBP was raised in rabbits immunized with keyhole limpet hemocyanin-conjugated RSPPMELQPPVSPQQSECNPVGALQ peptide (35) (GenScript). The immunoblots were analyzed by detecting the binding of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma) secondary antibody using Super Signal West Dura Extended reagent (Pierce) and imaged using a FluorChem SP digital camera (Alpha Innotech). When required, the membranes were stripped by treating with 0.1 M NaOH for 5 min at room temperature. Where indicated, the blots were quantitated by spot densitometry analysis using the FluorChem SP software.

RNA isolation, primer extension, and RT-PCR.

For reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), total RNA was isolated 2 days posttransfection using TRI reagent (Sigma). Following treatment with Turbo DNase (Roche), RNA was subjected to oligo(dT)-primed reverse transcription using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (New England BioLabs). Primers used to amplify TAR from transfected HeLa cells were HeLaF, GGGTCTCTCTGGTTAGACCAGATCTGAGC, and HeLaR, TCAGTCTAGAAGCCATGGTCTCTGTTTGA. To amplify TAR from ACH2 cells, the same forward primer was used in combination with ACH2R, AGTCCCTGTTCGGGCGCCA. Other gene-specific primers used in this study were as follows: Tat (F, CATCCCGGGTCTCTCTGGTTAGACC; R, CGCTCTAGAAGCCATGGCGGTCTCTCCTCTG); TRBP (F, GCAGGAGTATGGGACCAGAA; R, GTCATCATCAGGCTCCACCT); β-actin (F, GGACTTCGAGCAAGAGATGG; R, CACCTTCACCGTTCCAGTTT). The PCR products were resolved on 2% agarose and analyzed by ethidium bromide staining. For quantitative PCR, total RNA was isolated from primary cells using the PrepEase RNA isolation kit (USB) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Following oligo(dT)-primed reverse transcription, real-time PCR was performed by using gene-specific primers for TRBP (F, GCCAGCCCACCGCAAAGAAT; R, TGCCACTCCCAATCTCAATG) and actin (F, CCTGGCACCCAGCACAAT; R, GCCGATCCACACGGAGTACT) and utilizing Sybr green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). The data were normalized to actin mRNA and analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

RESULTS

Inhibition of PKR activity abrogates the ability of TRBP to enhance HIV-1 replication.

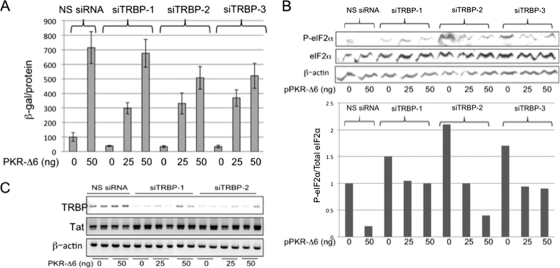

Many studies have demonstrated that TRBP can promote the expression of HIV-1 gene products, and several mechanisms have been proposed to explain this effect. To assess the relative importance of its role in the suppression of PKR activation, we first sought to confirm that physiological levels of TRBP are sufficient to affect viral gene expression. Three different siTRBPs were individually cotransfected into 293T cells together with the HIV-1 infectious molecular clone pLAI, and release of virus into the culture supernatant was assayed using reporter P4R5-MAGI cells. These cells are susceptible to infection by both X4 and R5 viruses, and infection is indicated by activation of LTR-driven β-galactosidase expression from an integrated reporter gene (32). In each case, the production of infectious virus was suppressed by approximately 60% in the presence of siTRBP, compared to cells transfected with an NS siRNA (Fig. 1A, compare bars corresponding to transfections with siTRBPs to that with NS siRNA, in the absence of pPKR-Δ6). We reasoned that the extent to which the decrease seen in viral replication upon TRBP depletion could be restored by concurrent inhibition of PKR activation would reflect the PKR-dependent role of TRBP in HIV-1 replication. In the absence of TRBP knockdown, cotransfection of cells with pLAI and a plasmid carrying a dominant negative PKR inhibitor, pPKR-Δ6 (33), viral replication was increased by almost 7-fold (Fig. 1A, compare NS siRNA transfections with and without cotransfected PKR-Δ6), highlighting the efficacy of PKR in suppressing viral replication. Notably, when PKR activity was inhibited by PKR-Δ6, TRBP knockdown did not diminish HIV-1 replication. As shown in Fig. 1A, in the presence of 50 ng pPKR-Δ6, there was no significant reduction in HIV-1 replication in cells cotransfected with siTRBP-1 compared to cells with similar amounts of NS siRNA. At the highest dose tested for PKR-Δ6, the inhibition of viral replication in the presence of siTRBP-2 and -3 was only ∼25%, compared to 60% inhibition in the absence of suppression of PKR by PKR-Δ6.

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of PKR activation prevents the suppression of HIV-1 replication by TRBP knockdown in 293T cells. (A) 293T cells were transfected with NS siRNA, siTRBP-1, siTRBP-2, or siTRBP-3, together with a constant amount of pLAI and different amounts of pPKR-Δ6, as indicated. Two days posttransfection, infectious virus released into the supernatant was determined in a P4R5 infection assay. Data are represented as β-galactosidase specific activity in the P4R5 indicator cells and shown as a percentage of control (NS siRNA, no pPKR-Δ6). Error bars represent standard deviations, derived from a total of 4 replicates. (B, upper panel) Total protein extracts prepared from transfected cells shown in panel A were immunoblotted for detection of P-eIF2α, total eIF2α, and actin. (Lower panel) Relative expression of P-eIF2α to total eIF2α as determined by densitometry analysis of the immunoblot shown in the upper panel. (C) Total RNA isolated from transfected cells as in panel A was analyzed by RT-PCR using primers specific for HIV-1 Tat mRNA, TRBP mRNA, and β-actin mRNA, with a limited number of PCR cycles to enable detection of quantitative differences in input RNA. Replicate samples are shown for each experimental condition.

Next, we assessed the effect of TRBP depletion, in the presence and absence of PKR-Δ6 expression, on phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor, eIF2α, a substrate for activated PKR. As shown in Fig. 1B (cells with no added pPKR-Δ6), the decrease in viral replication observed upon depletion of TRBP was accompanied by an increase in phosphorylation of eIF2α relative to total eIF2α. Further, the increase in P-eIF2α seen upon depletion of TRBP was reduced by coexpression of the PKR inhibitor PKR-Δ6, and this correlated with increased viral replication. Since each of the siTRBPs produced similar levels of reduction on HIV-1 replication, siTRBP-1 and -2 were used in further experiments. To confirm that the effects of TRBP depletion and PKR inhibition on viral replication occurred at the posttranscriptional level, we examined the level of HIV-1 Tat mRNA by RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 1C, there were no measurable changes in the level of Tat mRNA in cells that were either transfected with pPKR-Δ6, depleted of endogenous TRBP, or both, as would be expected for posttranscriptional regulation. The reduction in TRBP mRNA was confirmed in cells transfected with either siTRBP-1 or -2 (Fig. 1C). Taken together, the results shown in Fig. 1 suggest that TRBP, when expressed at physiological levels, acts to enhance HIV-1 replication primarily through its ability to inhibit the activation of PKR and the subsequent phosphorylation of eIF2α.

HIV-1 replication is not suppressed in Jurkat cells depleted of TRBP.

Jurkat CD4+ T cells readily support HIV-1 infection and replication but are relatively unresponsive to the anti-HIV-1 effects of alpha interferon (IFN-α), despite the induction of numerous interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) (26). IFN-α induction of PKR can be a major component of the cellular antiviral defense; however, in Jurkat cells, the production of relatively high levels of a truncated form of PKR, which can serve as a dominant negative inhibitor of its activation, may contribute to the poor antiviral response of these cells to IFN-α treatment (36, 37). The diminished ability of Jurkat cells to activate PKR makes them a good system in which to study the extent to which TRBP effects on HIV-1 gene expression are mediated through PKR in cells that more closely resemble the natural host of this virus than 293T cells.

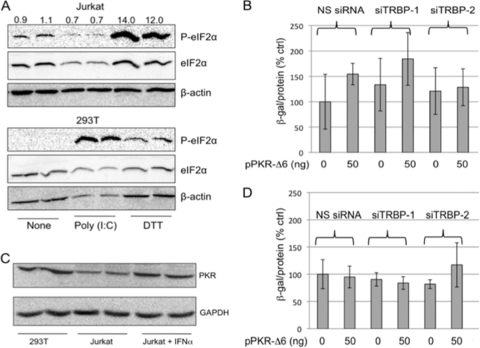

In order to confirm poor PKR activation in Jurkat cells, we monitored the phosphorylation of eIF2α in response to treatment with poly(I:C). As shown in Fig. 2A, eIF2α was not phosphorylated in Jurkat cells transfected with poly(I:C), although phosphorylaton of eIF2α was strongly induced by poly(I:C) transfection of control 293T cells. P-eIF2α was increased in both Jurkat and 293T cells after treatment with dithiothreitol (DTT), which induces phosphorylation by the endoplasmic reticulum-resident eIF2α kinase PERK (54), indicating that other stress-related eIF2α phosphorylation pathways are intact.

Fig. 2.

TRBP depletion does not reduce HIV-1 replication in Jurkat cells. (A) Jurkat cells (upper panels) or 293T cells (lower panels) were transfected with poly(I:C) (2.5 μg/ml) or treated with DTT (10 mM for 1 h), as indicated. Protein extracts were analyzed by 12% PAGE–SDS and immunoblotting with antibodies specific to P-eIF2α, total eIF2α, and β-actin. Numbers show the relative ratio of P-eIF2α to eIF2α, with the value for untreated cells set to 1.0. (B) Jurkat cells were transfected with NS or TRBP-specific siRNAs together with pLAI and different amounts of pPKR-Δ6, as indicated. The release of infectious virus into the supernatant was measured 2 days posttransfection by P4R5 infection assays. β-Galactosidase specific activity is shown as a percentage of the NS siRNA/no-PKR-Δ6 control. Error bars represent standard deviations from four replicates. (C) Protein lysates from 293T cells and Jurkat cells untreated or treated for 24 h with 1,000 U/ml IFN-α, as indicated, were immunoblotted using antibodies to detect PKR and GAPDH. (D) Jurkat cells were transfected as described for panel B, and after 18 h, cells were treated with 1,000 U/ml IFN-α for 24 h. Supernatant was collected, and P4R5 infection assays were performed and analyzed as for panel B. Error bars represent standard deviations from four replicates. In panels A and C, replicate samples are shown for each experimental condition.

The effects of TRBP knockdown and PKR-Δ6 expression on HIV-1 replication were then tested in Jurkat cells. As shown in Fig. 2B, neither overexpression of PKR-Δ6 nor knockdown of TRBP had a significant effect on the ability of HIV-1 to replicate in Jurkat cells, in sharp contrast to the effects seen in 293T cells. This result is consistent with predictions based on the inherent inability of Jurkat cells to activate PKR and the role for TRBP that is primarily to inhibit activation of PKR.

The basal level of expression of PKR is lower in Jurkat cells than in 293T cells, but its expression was induced by interferon treatment (Fig. 2C). If PKR is induced by IFN-α but its kinase activity cannot be fully activated due to the presence of the truncated dominant negative form (36, 37), we would expect to see little effect of either TRBP depletion or PKR-Δ6 overexpression on the replication of HIV-1 in Jurkat cells treated with IFN-α. Consistent with this prediction, PKR-Δ6 overexpression did not increase HIV-1 replication, and TRBP depletion did not suppress HIV-1 replication in IFN-α-treated Jurkat cells (Fig. 2D). These results, together with those obtained in 293T cells (Fig. 1), support the role of TRBP primarily as a suppressor of PKR activation during viral replication.

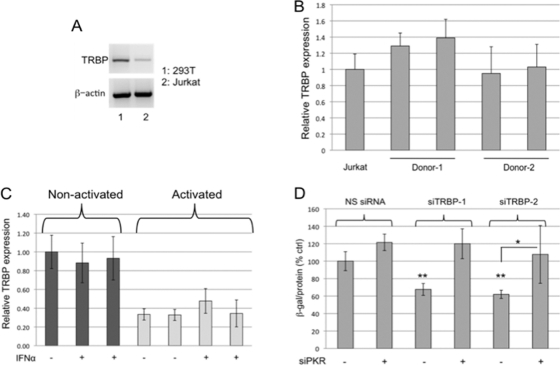

Reduced HIV-1 replication in TRBP-depleted primary CD4+ T cells is restored by knockdown of PKR.

Differences in the effects of TRBP depletion on HIV-1 replication in 293T cells and Jurkat cells serve to emphasize the fact that the role of TRBP will depend on its level of expression relative to its interaction partners, including PKR, in any given cell type. Notably, TRBP mRNA is expressed at lower basal levels in Jurkat cells than in 293T cells (Fig. 3A). In seeking to establish the effects of TRBP on HIV-1 replication in primary CD4+ T cells, we first analyzed the level of expression of TRBP mRNA in those cells and found it similar to the relatively low levels detected in Jurkat cells (Fig. 3B). Activation of the cells by treatment with IL-2 and PHA led to a further reduction of approximately 70% in the expression of TRBP mRNA (Fig. 3C). TRBP expression was not induced by treatment with IFN-α in either activated or nonactivated cells (Fig. 3C). Paradoxically, these data suggest that TRBP expression is reduced in activated cells that most strongly support HIV-1 replication, although PKR expression can be induced by IFN in those cells.

Fig. 3.

TRBP promotes HIV-1 replication in primary CD4+ T cells only when the cells express functional PKR. (A) RNA isolated from 293T and Jurkat cells was subjected to RT-PCR using primers specific for either TRBP mRNA or actin mRNA. (B) TRBP expression was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR in nonactivated primary CD4+ T cells isolated from two different donors. Data were normalized to actin and are represented as the fold change relative to TRBP mRNA expression in Jurkat cells. (C) Total RNA was isolated from nonactivated and activated CD4+ T cells, treated or not treated with 1,000 U/ml IFN-α for 24 h, and subjected to quantitative RT-PCR analysis to examine TRBP expression. Data were normalized to actin and are represented as the fold change relative to nonactivated, untreated T cells. (D) Activated primary CD4+ T cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, and 24 h posttransfection, cells were infected with HIV-LAI (4 ng p24). Production of infectious virus was determined by P4R5 infection assays 2 days postinfection. β-Galactosidase specific activity is shown as a percentage of the NS siRNA/no-siPKR control. Error bars represent standard deviations from four replicates. **, P < 0.005 (relative to NS siRNA/no-siPKR control); *, P < 0.05.

To test the effects of TRBP depletion on HIV-1 replication in activated primary CD4+ T cells, the cells were transfected with siTRBP-1 or -2, either with or without siRNA designed to target PKR mRNA, and then infected with HIV-1. As shown in Fig. 3D, depletion of TRBP by siRNAs 1 and 2 in activated T cells resulted in a reduction of approximately 40% in the production of infectious virus. As in 293T cells, the simultaneous knockdown of PKR abolished the effects of TRBP knockdown on HIV-1 replication. In addition, quantitative RT-PCR of viral RNA from these infected primary CD4+ T cells showed that viral RNA levels do not significantly change upon depletion of TRBP alone or in combination with PKR compared to NS siRNA controls (data not shown). Notably, the knockdown of PKR alone did not substantially increase HIV-1 replication, as it did in 293T cells. Moreover, the decrease in HIV-1 replication seen with TRBP knockdown was lower in primary T cells than that observed in 293T cells (40% versus 60%), possibly due to lower basal expression of PKR in primary T cells or to an inherent inability of T cells to fully activate PKR (37). To some degree, the decreased effects of knockdown of TRBP or PKR in these experiments relative to those seen using 293T cells could also reflect a lower transfection efficiency and a smaller overlap in the population of cells that are both transfected with the siRNAs and infected with the virus, compared to the cotransfection experiments performed in 293T and Jurkat cells. Nevertheless, it is evident that cotransfection of siPKR reduces the antiviral effects of siTRBP.

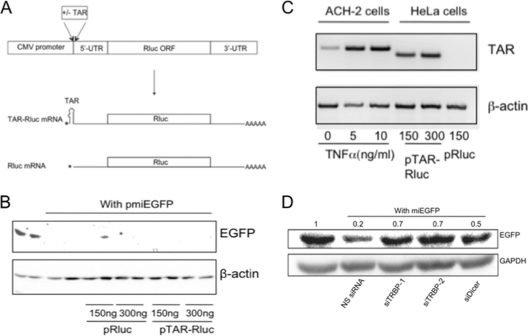

Expression of TAR-containing mRNAs does not affect the efficacy of RNA silencing.

A potential consequence of the TAR-TRBP interaction in HIV-1-infected cells is the diversion of TRBP away from its function in miRNA processing pathways, with the subsequent global suppression of RNAi. Since HIV-1 can be subject to restriction by cellular miRNAs (7, 30, 41, 48, 52), this has been suggested to be a mechanism by which the virus avoids RNAi-based antiviral defenses (22). Consistent with this idea, the introduction of in vitro-transcribed TAR RNA into cells has been reported to suppress the efficacy of RNAi silencing (3). However, our subsequent efforts to extend this finding using bona fide HIV-1 transcripts as a source of TAR failed to produce any inhibitory effect on RNAi silencing (48). To eliminate possible complications from other viral components that could potentially mask suppressive effects of TAR on RNAi, we utilized reporter plasmids that encodes Renilla luciferase (Rluc) driven from a CMV promoter. The plasmid pTAR-Rluc encodes a transcript with a TAR element at the very 5′ end of the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR), and the plasmid pRluc does not contain the TAR region (Fig. 4A). The precise transcriptional start site and the presence or absence of the entire TAR sequence at the 5′ end of the luciferase transcripts was confirmed by primer extension analysis of RNA isolated from HeLa cells transfected with these plasmids (data not shown). The plasmids were then used to test the effect of expression of TAR-containing mRNAs on the potency of silencing of an EGFP reporter by a cotransfected miEGFP construct (pmiEGFP). HeLa cells were used in these experiments to model them after those reported initially (3) and because of their high transfection efficiency. As shown in Fig. 4B, EGFP expression was substantially silenced by miEGFP, and there was no difference in the efficacy of silencing observed in the presence of increasing amounts of pRluc or pTAR-Rluc. Importantly, the cotransfection of pRluc or pTAR-Rluc with the EGFP reporter plasmid did not affect the expression of EGFP in the absence of miEGFP (data not shown). To confirm that sufficient TAR can be produced from pTAR-Rluc to mimic conditions in infected cells, RT-PCR was used to compare the amount of TAR RNA present in cells with replicating HIV-1 to that in cells transfected with pTAR-Ruc. As shown in Fig. 4C, the level of TAR produced in the pTAR-Rluc-transfected cell population was similar to that found in TNF-α-stimulated ACH-2 cells (19), while no TAR RNA was detected in HeLa cells transfected with the control plasmid, pRluc. Further, as shown in Fig. 4D, depletion of TRBP by siRNAs can prevent the silencing of EGFP by miEGFP, confirming that TRBP is required for RNA silencing in these cells. Results from these experiments support our earlier findings that TRBP binding to TAR in infected cells is unlikely to affect global levels of RNA interference (48).

Fig. 4.

The presence of TAR-containing mRNA does not reduce the silencing capacity of cells. (A) Schematic depicting the plasmid constructs pTAR-Rluc and pRluc and the corresponding Renilla luciferase transcripts. (B) Total protein extracts from HeLa cells transfected with the indicated plasmids were immunoblotted and analyzed for EGFP expression. Actin served as a loading control. Replicate samples are shown for each experimental condition. (C) RT-PCR was performed on total RNA obtained from either TNF-α-stimulated ACH-2 cells or transfected HeLa cells, as indicated, using primers specific for the HIV-1 TAR-containing 5′-UTR (upper panel) or actin mRNA (lower panel). (D) HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids encoding EGFP and miEGFP along with siRNAs, as indicated, and EGFP silencing was assayed by immunoblotting of total protein lysates obtained 2 days posttransfection using antibodies against EGFP and GAPDH. Numbers indicate silencing relative to the no-miEGFP control, which was set at 1.0.

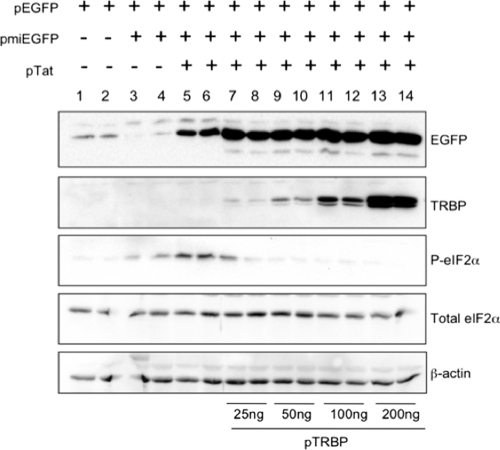

Overexpression of TRBP inhibits TAR-mediated activation of PKR.

To further examine the effects of TAR-TRBP interactions on PKR activation and on the efficacy of RNA silencing, we used P4R5 cells, a HeLa-derived HIV-1 indicator cell line in which an integrated copy of the HIV-1 LTR drives expression of a β-galactosidase gene (32). Transfection of these cells with a plasmid expressing the viral transactivator protein Tat induces transcription of TAR-containing β-galactosidase mRNA from the LTR. Results in Fig. 5 show that in the absence of Tat, the expression of EGFP from a reporter plasmid was efficiently silenced in these cells by cotransfection with p-miEGFP. Cotransfection with pTat rescued the expression of EGFP (Fig. 5, compare lanes 3 and 4 to lanes 5 and 6). This increase in EGFP expression could either represent transcriptional activation of the EGFP reporter by overexpressed Tat, an effect demonstrated previously that is independent of RNAi (38, 48), or true suppression of RNAi due to sequestration of TRBP by the TAR element associated with β-galactosidase mRNAs. If the latter were indeed the case, overexpression of TRBP should restore the silencing efficacy of miEGFP that is lost in the presence of Tat. Instead, we observed a further increase in EGFP levels when TRBP was overexpressed, which we attributed to TRBP inhibition of PKR. Transfection with pTat, in the absence of TRBP overexpression, resulted in an increase in phosphorylation of eIF2α, most likely due to the activation of PKR by the structured TAR RNA, as has been shown previously (Fig. 2, lanes 5 and 6) (39). The increase in P-eIF2α was completely abolished upon overexpression of TRBP, which is consistent with previous observations that overexpression of TRBP can prevent the TAR-mediated activation of PKR (Fig. 2, lanes 7 to 14) (2, 13). It is important to note that the steady-state levels of total eIF2α did not change significantly, indicating that neither Tat nor TAR affects global levels of eIF2α. Overall, these results support the conclusion that the role of TRBP in RNAi is unaffected by the expression of TAR-containing RNAs, but instead, TRBP is important in preventing the activation of PKR by TAR RNA.

Fig. 5.

Overexpression of TRBP prevents the TAR-dependent phosphorylation of eIF2α. P4R5 cells were transfected with 150 ng of p-ds-EGFP along with 50 ng p-miEGFP and 50 ng pTat, as specified, and total protein extracts prepared 2 days posttransfection were separated on a 12% PAGE–SDS gel and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Paired lanes are loaded with protein from replicate samples, as indicated.

DISCUSSION

TRBP is recognized as a cellular protein that can help to promote HIV-1 replication in infected cells, although its mechanism of action remains incompletely understood. The strong binding affinity of TRBP for the conserved and structured TAR element at the very 5′ end of HIV-1 transcripts has led to investigations of its role in facilitating translation of viral mRNAs through unwinding of the TAR structure or by preventing the activation of PKR (9, 13, 16). Since TRBP is a cofactor for Dicer in the assembly and maturation of RISC during RNA interference (8, 28), it has also been suggested that binding to TAR could serve to sequester TRBP, thereby diminishing a cellular RNAi-mediated antiviral response (3). We present evidence here that, when expressed at physiological levels, TRBP only promotes HIV-1 gene expression to the extent that cells are capable of activating PKR, and there is no limitation of the silencing capacity of cells expressing TAR-containing RNAs.

The induction of PKR by type I interferons and the activation of its kinase activity by dsRNA is a potent source of eukaryotic innate antiviral immunity, and many viruses have evolved countermeasures to this host cell defense (reviewed in references 4, 25, and 34). It is clear that activated PKR can severely restrict HIV-1 replication (14, 42), and early work on HIV-1 identified several viral strategies that might prevent a full PKR-mediated antiviral response in infected cells. For instance, the viral transactivator protein Tat was shown to downregulate PKR expression and prevent its induction by IFN treatment (46, 51). Tat was also shown to bind directly to PKR, thus either inhibiting the activation of PKR (5, 40) or acting as a pseudosubstrate for PKR with consequent increases in the affinity of phosphorylated Tat for TAR and transactivation of the LTR (18). The viral TAR element can also interact with PKR, and this has variously been reported to promote or inhibit PKR activation (27, 39). TAR, like other dsRNAs, may act in a dose-dependent manner to promote PKR dimerization, autophosphorylation, and activation when present at low levels or, when present in excess relative to PKR, to prevent dimerization and subsequent kinase activation (27, 39).

PKR plays an important role in growth and differentiation, and its activity is closely regulated by a number of cellular proteins, including TRBP (20). Our results confirmed that TRPB can help to establish a cellular environment favorable to HIV-1 replication, since knockdown of TRBP correlated with reduced production of infectious virus in both 293T and primary human CD4+ T cells. However, the ability of TRBP to promote HIV-1 replication was directly related to the ability of host cells to mount a PKR-mediated antiviral response, and when PKR activation was otherwise prevented, TRBP had no further role in promoting viral replication. This is consistent with earlier studies where naturally low levels of TRBP in astrocytes were shown to allow the activation of PKR by HIV-1, resulting in highly restricted viral replication in those cells (1, 42). However, in other experiments where TRBP was depleted by knockdown in HeLa cells, the decrease in viral replication did not correlate with a significant activation of PKR, leading the authors to conclude that TRBP had PKR-independent effects on viral replication, perhaps acting to unwind the TAR structure (9, 16). We cannot explain this discrepancy, although it may be due to differences in the efficiency of knockdown of TRBP or to other differences in the cell systems used.

While our studies indicate the importance of preventing the activation of PKR to robust replication of the HIV-1 virus, they do not specifically address the mechanism by which PKR is controlled by TRBP in infected cells. Additional cellular proteins with potential effects on viral replication, including ADAR (adenosine deaminase acting on dsRNA) and PACT (protein activator of PKR), have been reported to interact with both PKR and TRBP, modulating their function (10–12, 24, 49). The final outcome of these sometimes competing events will depend on the balance of the different interacting partners present in cells throughout the course of infection, as well as the extent of posttranslational modifications that can affect their relative affinities for different binding partners (11, 45, 49). To fully understand how HIV-1 counters the antiviral effects of PKR activation, it will be essential to study the physiological levels, modifications, and interactions of numerous components of this regulatory network as viral replication proceeds in primary human lymphocytes.

Beyond its function as an inhibitor of PKR, TRBP has been implicated in the restriction of HIV-1 gene expression by mechanisms that depend on its role as a Dicer cofactor in RNA interference. Although RNAi is well documented as an antiviral defense in plants and invertebrates (15), the significance of this mechanism in higher eukaryotes has been controversial, and its potential as a defense, particularly against retroviruses, has been strongly questioned (50, 53). Therefore, we asked whether the TAR element, when present in the context of its position at the 5′ end of an mRNA, could bind TRBP and suppress silencing. We found no evidence of a reduced capacity for processing or function of miRNAs in cells that expressed reporter TAR mRNAs synthesized from either a CMV promoter or the viral LTR. Our results argue against a role for TRBP sequestration by TAR RNAs produced during virus replication and reinforce our earlier work and that of others that showed no effect of HIV-1 gene products on the cellular RNA interference machinery (38, 48). In contrast to TRBP, the depletion of other members of the miRNA machinery, such as Dicer, Drosha, GW182, and Ago2, has been shown to increase HIV-1 replication in several cell systems (7, 41, 48, 52). This implies that any antiviral effects that TRBP may exert on HIV-1 through the RNAi pathway can be masked by its ability to inhibit PKR activation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tom Dever (NIH) for kindly providing pPKR-Δ6 and Michele Kutzler (Drexel University College of Medicine) for her help with primary cell experiments. The following reagent was obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: pLAI.2 from Keith Peden, courtesy of the MRC AIDS Directed Program.

This work was supported by a grant to L.F.S. from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Health, Tobacco Formula Funds.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 September 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bannwarth S., et al. 2001. Organization of the human tarbp2 gene reveals two promoters that are repressed in an astrocytic cell line. J. Biol. Chem. 276:48803–48813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Benkirane M., et al. 1997. Oncogenic potential of TAR RNA binding protein TRBP and its regulatory interaction with RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR. EMBO J. 16:611–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bennasser Y., Yeung M. L., Jeang K. T. 2006. HIV-1 TAR RNA subverts RNA interference in transfected cells through sequestration of TAR RNA-binding protein, TRBP. J. Biol. Chem. 281:27674–27678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boo K. H., Yang J. S. 2010. Intrinsic cellular defenses against virus infection by antiviral type I interferon. Yonsei Med. J. 51:9–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brand S. R., Kobayashi R., Mathews M. B. 1997. The Tat protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is a substrate and inhibitor of the interferon-induced, virally activated protein kinase, PKR. J. Biol. Chem. 272:8388–8395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carpick B. W., et al. 1997. Characterization of the solution complex between the interferon-induced, double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase and HIV-I trans-activating region RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 272:9510–9516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chable-Bessia C., et al. 2009. Suppression of HIV-1 replication by microRNA effectors. Retrovirology 6:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chendrimada T. P., et al. 2005. TRBP recruits the Dicer complex to Ago2 for microRNA processing and gene silencing. Nature 436:740–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Christensen H. S., et al. 2007. Small interfering RNAs against the TAR RNA binding protein, TRBP, a Dicer cofactor, inhibit human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat expression and viral production. J. Virol. 81:5121–5131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clerzius G., et al. 2009. ADAR1 interacts with PKR during human immunodeficiency virus infection of lymphocytes and contributes to viral replication. J. Virol. 83:10119–10128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clerzius G., Gelinas J. F., Gatignol A. 2011. Multiple levels of PKR inhibition during HIV-1 replication. Rev. Med. Virol. 21:42–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Daher A., et al. 2009. TRBP control of PACT-induced phosphorylation of protein kinase R is reversed by stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:254–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Daher A., et al. 2001. Two dimerization domains in the trans-activation response RNA-binding protein (TRBP) individually reverse the protein kinase R inhibition of HIV-1 long terminal repeat expression. J. Biol. Chem. 276:33899–33905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dimitrova D. I., et al. 2005. Lentivirus-mediated transduction of PKR into CD34(+) hematopoietic stem cells inhibits HIV-1 replication in differentiated T cell progeny. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 25:345–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ding S. W. 2010. RNA-based antiviral immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10:632–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dorin D., et al. 2003. The TAR RNA-binding protein, TRBP, stimulates the expression of TAR-containing RNAs in vitro and in vivo independently of its ability to inhibit the dsRNA-dependent kinase PKR. J. Biol. Chem. 278:4440–4448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eekels J. J., Geerts D., Jeeninga R. E., Berkhout B. 2010. Long-term inhibition of HIV-1 replication with RNA interference against cellular co-factors. Antiviral Res. 89:43–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Endo-Munoz L., Warby T., Harrich D., McMillan N. A. 2005. Phosphorylation of HIV Tat by PKR increases interaction with TAR RNA and enhances transcription. Virol. J. 2:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Folks T. M., et al. 1989. Tumor necrosis factor alpha induces expression of human immunodeficiency virus in a chronically infected T-cell clone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:2365–2368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Garcia M. A., Meurs E. F., Esteban M. 2007. The dsRNA protein kinase PKR: virus and cell control. Biochimie 89:799–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gatignol A., Buckler-White A., Berkhout B., Jeang K. T. 1991. Characterization of a human TAR RNA-binding protein that activates the HIV-1 LTR. Science 251:1597–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gatignol A., Laine S., Clerzius G. 2005. Dual role of TRBP in HIV replication and RNA interference: viral diversion of a cellular pathway or evasion from antiviral immunity? Retrovirology 2:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Geballe A. P., Gray M. K. 1992. Variable inhibition of cell-free translation by HIV-1 transcript leader sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:4291–4297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gelinas J. F., Clerzius G., Shaw E., Gatignol A. 2011. Enhancement of replication of RNA viruses by ADAR1 via RNA editing and inhibition of RNA-activated protein kinase. J. Virol. 85:8460–8466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. George C. X., et al. 2009. Tipping the balance: antagonism of PKR kinase and ADAR1 deaminase functions by virus gene products. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 29:477–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goujon C., Malim M. H. 2010. Characterization of the alpha interferon-induced postentry block to HIV-1 infection in primary human macrophages and T cells. J. Virol. 84:9254–9266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gunnery S., Rice A. P., Robertson H. D., Mathews M. B. 1990. Tat-responsive region RNA of human immunodeficiency virus 1 can prevent activation of the double-stranded-RNA-activated protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:8687–8691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haase A. D., et al. 2005. TRBP, a regulator of cellular PKR and HIV-1 virus expression, interacts with Dicer and functions in RNA silencing. EMBO Rep. 6:961–967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heinicke L. A., et al. 2009. RNA dimerization promotes PKR dimerization and activation. J. Mol. Biol. 390:319–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huang J., et al. 2007. Cellular microRNAs contribute to HIV-1 latency in resting primary CD4+ T lymphocytes. Nat. Med. 13:1241–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim I., Liu C. W., Puglisi J. D. 2006. Specific recognition of HIV TAR RNA by the dsRNA binding domains (dsRBD1-dsRBD2) of PKR. J. Mol. Biol. 358:430–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kimpton J., Emerman M. 1992. Detection of replication-competent and pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus with a sensitive cell line on the basis of activation of an integrated beta-galactosidase gene. J. Virol. 66:2232–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Koromilas A. E., Roy S., Barber G. N., Katze M. G., Sonenberg N. 1992. Malignant transformation by a mutant of the IFN-inducible dsRNA-dependent protein kinase. Science 257:1685–1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Langland J. O., Cameron J. M., Heck M. C., Jancovich J. K., Jacobs B. L. 2006. Inhibition of PKR by RNA and DNA viruses. Virus Res. 119:100–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee J. Y., et al. 2004. Merlin, a tumor suppressor, interacts with transactivation-responsive RNA-binding protein and inhibits its oncogenic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 279:30265–30273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li S., Koromilas A. E. 2001. Dominant negative function by an alternatively spliced form of the interferon-inducible protein kinase PKR. J. Biol. Chem. 276:13881–13890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li S., Nagai K., Koromilas A. E. 2000. A diminished activation capacity of the interferon-inducible protein kinase PKR in human T lymphocytes. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:1598–1606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lin J., Cullen B. R. 2007. Analysis of the interaction of primate retroviruses with the human RNA interference machinery. J. Virol. 81:12218–12226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maitra R. K., et al. 1994. HIV-1 TAR RNA has an intrinsic ability to activate interferon-inducible enzymes. Virology 204:823–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McMillan N. A., et al. 1995. HIV-1 Tat directly interacts with the interferon-induced, double-stranded RNA-dependent kinase, PKR. Virology 213:413–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nathans R., et al. 2009. Cellular microRNA and P bodies modulate host-HIV-1 interactions. Mol. Cell 34:696–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ong C. L., et al. 2005. Low TRBP levels support an innate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance in astrocytes by enhancing the PKR antiviral response. J. Virol. 79:12763–12772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Park H., et al. 1994. TAR RNA-binding protein is an inhibitor of the interferon-induced protein kinase PKR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:4713–4717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Parkin N. T., et al. 1988. Mutational analysis of the 5′ non-coding region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: effects of secondary structure on translation. EMBO J. 7:2831–2837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Paroo Z., Ye X., Chen S., Liu Q. 2009. Phosphorylation of the human microRNA-generating complex mediates MAPK/Erk signaling. Cell 139:112–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Roy S., et al. 1990. Control of the interferon-induced 68-kilodalton protein kinase by the HIV-1 tat gene product. Science 247:1216–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sanghvi V. R., Steel L. F. 2011. Expression of interfering RNAs from an HIV-1 Tat-inducible chimeric promoter. Virus Res. 155:106–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sanghvi V. R., Steel L. F. 2011. A re-examination of global suppression of RNA interference by HIV-1. PLoS One 6:e17246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Singh M., Castillo D., Patel C. V., Patel R. C. 2011. Stress-induced phosphorylation of PACT reduces its interaction with TRBP and leads to PKR activation. Biochemistry 50:4550–4560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Skalsky R. L., Cullen B. R. 2010. Viruses, microRNAs, and host interactions. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64:123–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Soumelis V., et al. 2001. Depletion of circulating natural type 1 interferon-producing cells in HIV-infected AIDS patients. Blood 98:906–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Triboulet R., et al. 2007. Suppression of microRNA-silencing pathway by HIV-1 during virus replication. Science 315:1579–1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Umbach J. L., Cullen B. R. 2009. The role of RNAi and microRNAs in animal virus replication and antiviral immunity. Genes Dev. 23:1151–1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wek R. C., Jiang H. Y., Anthony T. G. 2006. Coping with stress: eIF2 kinases and translational control. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34:7–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]