Abstract

Lassa virus (LASV) causing hemorrhagic Lassa fever in West Africa, Mopeia virus (MOPV) from East Africa, and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) are the main representatives of the Old World arenaviruses. Little is known about how the components of the arenavirus replication machinery, i.e., the genome, nucleoprotein (NP), and L protein, interact. In addition, it is unknown whether these components can function across species boundaries. We established minireplicon systems for MOPV and LCMV in analogy to the existing LASV system and exchanged the components among the three systems. The functional and physical integrity of the resulting complexes was tested by reporter gene assay, Northern blotting, and coimmunoprecipitation studies. The minigenomes, NPs, and L proteins of LASV and MOPV could be exchanged without loss of function. LASV and MOPV L protein was also active in conjunction with LCMV NP, while the LCMV L protein required homologous NP for activity. Analysis of LASV/LCMV NP chimeras identified a single LCMV-specific NP residue (Ile-53) and the C terminus of NP (residues 340 to 558) as being essential for LCMV L protein function. The defect of LASV and MOPV NP in supporting transcriptional activity of LCMV L protein was not caused by a defect in physical NP-L protein interaction. In conclusion, components of the replication complex of Old World arenaviruses have the potential to functionally and physically interact across species boundaries. Residue 53 and the C-terminal domain of NP are important for function of L protein during genome replication and transcription.

INTRODUCTION

The family Arenaviridae comprises more than 20 virus species and is divided into the Old World and the New World complexes (9). Main representatives of the Old World complex are the prototype arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), Lassa virus (LASV) causing hemorrhagic Lassa fever in West Africa (14), and Mopeia virus (MOPV) from East Africa. MOPV is closely related to LASV but, in contrast to the latter, is neither associated with human disease nor pathogenic in animal models (39).

The genomes of arenaviruses consist of two negative-strand RNA segments. The large (L) segment and the small (S) segment each contain two genes in opposite orientation separated by an intergenic region (IGR). During genome replication, full-length copies of S and L RNA are synthesized. Viral transcripts contain a cap structure and terminate within the IGR (1). The IGR contains a stable secondary structure and plays a role in both transcription termination and virus assembly (31). The L RNA encodes the small Z protein and the 220-kDa L protein (26). The latter is a multidomain protein (5, 20) that harbors the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) (13, 17) and a cap-snatching endonuclease (22, 29). It oligomerizes (34) and interacts with the viral promoter sequences (16, 20). Z protein functions as a matrix protein (30, 37) and interacts with L protein (19, 40). The S RNA encodes the glycoprotein precursor (GPC) and the nucleoprotein (NP). The virus genome, NP, and L protein represent the minimal cis- and trans-acting components required for replication and transcription (15, 21, 24). NP is the major component of the viral ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. It physically associates with itself as well as with L and Z proteins (7, 19, 23, 35). Association with Z protein and with the ALIX/AIP1, an ESCRT-associated host protein, is important for incorporation of NP into virus-like particles (7, 23, 35, 36). In addition, NP acts as an interferon antagonist (27, 28). Recently published X-ray crystallographic data revealed a nucleotide binding site in the N terminus and a 3′-5′ exoribonuclease in the C terminus of NP; the latter is critical for NP to function as an interferon antagonist (18, 32).

While a substantial amount of information has been accumulated on the individual components of the replication machinery, specifically NP and L protein, little is known about how these components physically and functionally interact during replication and transcription. In addition, it is not known whether these components are functional across species boundaries. To tackle these questions, we have established minireplicon systems for MOPV and LCMV in analogy to the LASV system (15) and have exchanged the components among the three systems and tested for functional and physical integrity of the resulting complexes. On the one hand, this strategy revealed that components of the replication machineries of various arenavirus species are able to functionally and physically interact. On the other hand, barriers preventing the functional cooperation of L protein and NP between more distantly related viruses were identified. Generation of a large set of chimeric NPs to overcome this species-specific block led to the identification of two sites in NP that are important for L protein function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus propagation.

Vero cells in 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks were inoculated with MOPV strain AN 21366-BNI (seed stock was obtained from National Collection of Pathogenic Viruses, United Kingdom) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01. After 4 days, the supernatant was cleared by low-speed centrifugation and virus was pelleted from the cleared material by ultracentrifugation. The pellet was resuspended in water, and virus RNA was purified by using the QIAamp viral RNA kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Direct sequencing of MOPV AN 21366-BNI.

Overlapping fragments of S and L RNAs of MOPV strain AN 21366-BNI were amplified by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) and directly sequenced. The conserved L RNA termini were sequenced as described previously (15). In brief, purified virus RNA was treated with 5 U of tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (Epicentre) to generate 5′ monophosphorylated termini. These were ligated with the 3′ termini with 10 U of T4 RNA ligase (Biolabs) at 17°C for 16 h. Reverse transcription and PCR were done across the 5′-3′ junction, and the resulting PCR products were sequenced.

Construction of plasmids for MOPV and LCMV minireplicon systems.

Purified RNA was reverse transcribed by using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with virus-specific primers, and the cDNA was amplified with the Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) or the Expand high-fidelity PCR system (Roche). MOPV genes were cloned into expression vector pCITE-2a containing a T7 RNA polymerase promoter, an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES), and a favorable Kozak sequence. Differences from the consensus sequence of strain AN 21366-BNI were removed by site-directed mutagenesis or by combining fragments of different clones. The final NP gene sequence in pCITE-Mop-NP matched the consensus sequence except for a silent A-G exchange at position 198. Prior to construction of pCITE-Mop-L, the pCITE-2a expression vector was modified by introducing a unique MluI restriction site into the ampicillin resistance gene via PCR mutagenesis. Three overlapping fragments of the L gene were amplified and cloned into pCITE-2-(MluI) via a PCR-based cloning strategy: L1 (start codon to SpeI site), L2 (SpeI to AvaI site), and L3 (AvaI site to stop codon). Differences from the consensus sequence of strain AN 21366-BNI were removed by site-directed mutagenesis or by combining fragments of different clones. Fragments L2 and L3 were assembled by ligation of the MluI-AvaI fragment of pCITE-Mop-L2 with the AvaI-MluI fragment of pCITE-Mop-L3, resulting in pCITE-Mop-L2/3. Subsequently, fragment L1 was joined with fragment L2/3 by ligation of the MluI-SpeI fragment of pCITE-Mop-L1 with the SpeI-MluI fragment of pCITE-L2/3, resulting in pCITE-Mop-L. The final L gene sequence in pCITE-Mop-L matched the consensus sequence except for a silent A-G exchange at position 2892 and a silent G-A exchange at position 3684. Complete LCMV NP and L genes were amplified from pC-NP and pC-Cl13-L (12), respectively, using Phusion DNA polymerase and subcloned into pCITE-2a, yielding pCITE-LCM-NP and pCITE-LCM-L. Constructs for expression of LASV NP and L protein have been described previously (15) and are designated pCITE-Las-NP and pCITE-Las-L. For transfection, the functional cassettes of pCITE-L constructs (T7 RNA polymerase promoter, IRES, and L gene) were amplified with Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes), purified by using a PCR purification kit (Macherey & Nagel), and quantified spectrophotometrically. For immunoblot and immunoprecipitation studies, hemagglutinin (HA) tags were fused to the C termini of NP genes integrated in pCITE vector via PCR mutagenesis. L genes were tagged with 3× FLAG sequences.

MOPV and LCMV minigenome (MG) plasmids were constructed in analogy to and on the basis of the genomic S RNA MG of LASV (pLAS-MG) integrated in vector pX12ΔT (16). pLAS-MG comprises the following elements: T7 RNA polymerase promoter followed by a single G residue, 5′ untranslated region (5′-UTR), chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene, IGR, Renilla luciferase (Ren-Luc) gene in reverse orientation, and 3′-UTR. In several PCR-mediated cloning steps, regulatory elements of LASV S RNA were replaced by the corresponding elements of MOPV or LCMV, resulting in pMOP-MG and pLCM-MG. In addition, various LASV/MOPV MG chimeras (pLAS/MOP-MG) were generated. For transfection, the MG, including T7 RNA polymerase promoter, was amplified for 30 cycles with Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes), 10 ng of pLAS-MG, pMOP-MG, pLAS/MOP-MG, or pLCM-MG as a template, vector-specific primer pUC-fwd, and a virus-specific reverse primer binding to the 3′ terminus of the MG to generate a functional 3′ end as described previously (16). Amplified MGs were purified by using a PCR purification kit (Macherey & Nagel) and quantified spectrophotometrically.

LASV/LCMV NP chimeras and mutants.

NP chimeras and mutants were generated via a classical two-step PCR mutagenesis approach (17). First, an N-terminal fragment including the T7 RNA polymerase promoter and IRES was amplified with Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) for 30 cycles by using 10 ng of pCITE-Las-NP (or pCITE-LCM-NP as appropriate) as a template and the primer combination pUC-fwd/NP-mut-rev. The corresponding C-terminal fragment was amplified by using pCITE-LCM-NP (or pCITE-Las-NP as appropriate) as a template and primers NP-mut-fwd/pUC-rev. The template NP genes contained a C-terminal HA tag to facilitate detection of the chimeras. Primer NP-mut-rev was reverse complementary to the corresponding NP-mut-fwd primer. One half of the primer sequence was LASV specific, while the other half was LCMV specific for generation of chimeras; both primers contained a mutation in the middle of the primer sequence for introduction of point mutations. N- and C-terminal PCR products were gel purified and fused together in a second PCR with aliquots of both fragments as a template and primers pUC-fwd and pUC-rev. The resulting PCR products were purified using a PCR purification kit (Macherey & Nagel), quantified spectrophotometrically, and used for transfection without prior cloning as described previously (17). Selected PCR products were cloned, and the chimeric NP gene was used as a template for generation of more complex chimeras. The presence of the fusion site or artificial mutation was ascertained by sequencing the final PCR product. The wild-type NP gene expression cassette was amplified using primers pUC-fwd/pUC-rev and served as a control for the transfection experiment.

Cells and transfections.

BSR-T7/5 cells stably expressing T7 RNA polymerase (6) were grown in Glasgow's minimal essential medium (GMEM) (GIBCO) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS). Every second passage, 1 mg Geneticin (GIBCO) per ml of medium was added to the cells. BHK-21/J cells were grown in minimal essential medium (MEM) with Earle's salts (PAA Laboratories) supplemented with 7.5% FCS. All transfections were performed with 3 μl Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) per μg DNA in cell culture medium without supplements. Medium was replaced at 4 h after transfection by fresh medium complemented with FCS.

Replicon assay.

BSR-T7/5 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well of a 24-well plate at 1 day prior to transfection. Cells in a well were transfected with 300 ng of MG PCR product, 300 ng of L gene PCR product, 300 ng of pCITE-NP or NP gene PCR product, and 10 ng of pCITE-FF-luc (expression construct for firefly luciferase) as a transfection control. The amount of transfected DNA was kept constant within an experiment by adding empty pCITE-2a vector. One day after transfection, total RNA was prepared for Northern blotting or cells were lysed in 100 μl of passive lysis buffer (Promega) per well, and 20 μl of the lysate was assayed for firefly luciferase and Ren-Luc activity using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) as described by the manufacturer. Ren-Luc levels were corrected with the firefly luciferase levels (resulting in standardized relative light units [sRLU]) to compensate for differences in transfection efficiency or cell density.

Expression of NP and L protein.

BSR-T7/5 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well of a 24-well plate at 1 day prior to transfection. To enhance the expression levels of NP and L protein and facilitate detection of potentially less stable mutants, the cells were additionally inoculated with modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing T7 RNA polymerase (MVA-T7) (38) at an MOI of 5 for 1 h before transfection. Cells in a well of a 24-well plate were transfected with 500 ng of PCR product for expression of HA- or FLAG-tagged NP or L protein and lysed in 50 μl passive lysis buffer (Promega) containing complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) at 24 h after transfection. Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation, and the cytoplasmic lysate was mixed with 4× NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) complemented with dithiothreitol (DTT). Proteins were separated by 4 to 12% Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell), and detected by immunoblotting (see below).

Coimmunoprecipitation studies.

BHK-21/J cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well of a 24-well plate at 1 day before transfection and inoculated with MVA-T7 (38) at an MOI of 5 for 1 h before transfection. Cells in two wells of a 24-well plate were transfected with 1 μg pCITE-NP-HA and 1 μg pCITE-L-3xFLAG and lysed at 24 h posttransfection in 200 μl lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 40 μl complete protease inhibitor cocktail/ml [Roche]). Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation, and 150 μl supernatant was mixed with 300 μl 2× binding buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 400 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 2 mg bovine serum albumin/ml), 150 μl water, and 1 μl of anti-HA antibody solution (0.5 to 0.7 mg/ml) (H6908; Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated at 4°C overnight with gentle agitation. Protein G- or nProtein A-Sepharose 4 Fast Flow solution (30 μl as supplied by GE Healthcare) was added, and the mix was incubated for 1 h at 4°C with gentle agitation. Sepharose-coupled antibody-protein complexes were precipitated by centrifugation and washed four times with ice-cold 1× binding buffer and once with ice-cold 1× TNE buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA). Precipitated proteins were mixed with 4× NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) and DTT, separated by 4 to 12% Bis-Tris PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell), and detected by immunoblotting (see below).

Immunoblot analysis.

Nitrocellulose membranes were stained with Fast Green FCF (Roth), blocked in 1× Roti-Block (Roth) overnight at room temperature, and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated anti-HA (1:1,000) (H6533; Sigma-Aldrich) or peroxidase-conjugated anti-FLAG M2 antibody (1:10,000) (A8592; Sigma-Aldrich) in phosphate-buffered saline–0.05% Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, protein bands were visualized by chemiluminescence using SuperSignal West Pico substrate (Pierce) and X-ray film (Kodak). Images were scanned and signals were quantified using TINA software (Raytest, Straubenhardt, Germany).

Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA of transfected or infected cells was purified by using TRIzol LS reagent (Invitrogen). RNA (5 to 10 μg) was separated in a 1.5% agarose–formaldehyde gel and transferred onto a Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Blots were prehybridized in 50% deionized formamide–0.5% SDS–5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–5× Denhardt's solution for 1 h at 68°C. Hybridization was done in the same buffer with an antisense 32P-labeled riboprobe targeting the Ren-Luc gene at 68°C for 16 h. The membrane was washed several times, and RNA bands were visualized by autoradiography using an FLA-7000 phosphorimager (Fujifilm).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The S and L RNA sequences for MOPV strain AN 21366-BNI have been submitted to GenBank and assigned accession numbers JN561684 and JN561685.

RESULTS

Establishment of minireplicon systems for LCMV and MOPV.

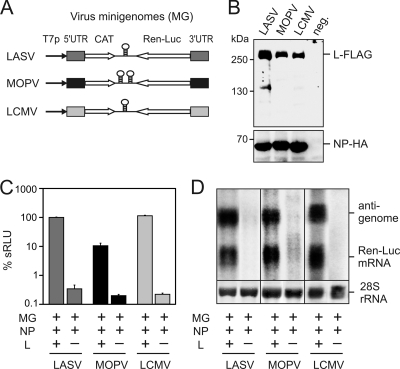

Minireplicon systems for LCMV strain Armstrong clone 13 and MOPV strain 21366 were constructed in analogy to the published replicon system for LASV (15). The MGs are based on the genomic S RNA segments of LCMV and MOPV, with the reporter genes for CAT and Ren-Luc replacing the viral genes for GPC and NP, respectively (Fig. 1A). Genes for the NPs and L proteins of LCMV and MOPV were cloned into the expression vector pCITE-2a under the control of a T7 RNA polymerase promoter and an IRES. Expression of both proteins was verified by immunoblotting (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Establishment of MOPV and LCMV minireplicon systems. (A) Schematic representation of MGs based on LASV, MOPV, and LCMV S RNAs. Stem-loop structures in the intergenic region are indicated. T7p, T7 RNA polymerase promoter; UTR, untranslated region; CAT, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene; Ren-Luc, Renilla luciferase gene. (B) Expression of NP and L proteins from the wild-type constructs used for the replicon assays. FLAG- and HA-tagged proteins were expressed in BHK-21/J cells, separated by PAGE, and detected by immunoblot analysis using antibodies against FLAG and HA tag, respectively. Negative control cells (neg.) were transfected with empty pCITE-2a. (C) Transcriptional activity of the replicon systems as measured by Ren-Luc reporter gene expression. Replicon assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Means and standard deviations from three independent transfection experiments are shown. Activity of the LASV system was set at 100%. sRLU, standardized relative light units. (D) Demonstration of antigenome and Ren-Luc mRNA synthesis by the replicon systems in Northern blotting. Transfection and Northern blotting were performed as described in Materials and Methods independently for each virus. The methylene blue-stained 28S rRNA is shown below the blot as a marker for gel loading and RNA transfer.

BSR-T7/5 cells were transfected with constructs for expression of the MGs, NPs, and L proteins of LASV, MOPV, and LCMV. Transcriptional replicon activity was measured via expression of the Ren-Luc reporter gene. Background activity was determined by replacing the L gene construct with empty vector. All three replicon systems showed Ren-Luc activity above background. Expression of the L genes of LASV and LCMV stimulated Ren-Luc activity by about 2.5 log units, while expression of the MOPV L gene stimulated Ren-Luc activity by only 1.5 log units (Fig. 1C). The 10-fold-reduced activity of the MOPV system compared to the LASV and LCMV systems was verified in several independent experiments and was not due to a reduced expression level of NP or L protein (Fig. 1B). To examine whether the MG is transcribed and replicated like an authentic virus genome, MG RNA was analyzed by Northern blotting. Both antigenome and mRNA were expressed by the three replicon systems (Fig. 1D), indicating that RNP complexes capable of mediating genome replication and transcription had been formed. In conclusion, functional replicon systems for LCMV and MOPV have been established, although the activity of the MOPV system is lower than those of the LCMV and LASV systems.

Relevance of cis-acting elements for the activity of MOPV and LASV systems.

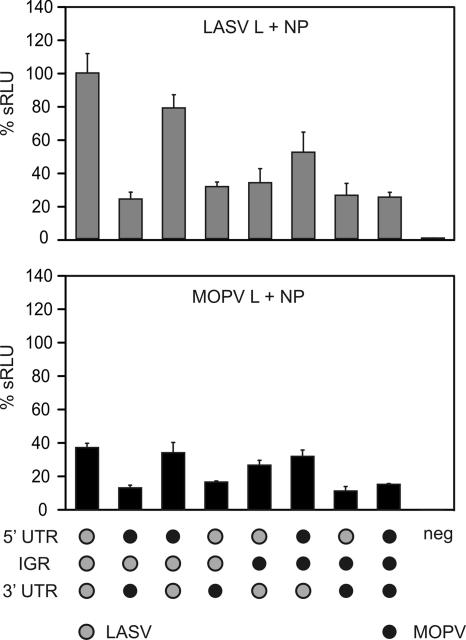

Except for the terminal 19 nucleotides of S and L RNAs, the UTRs and the IGR are variable in length and sequence among arenavirus species. Specifically, the IGR of MOPV S RNA contains two stem-loop structures (41), while those of most of the other arenaviruses, including LASV, contain only one stem-loop structure (2) (Fig. 1A). To test whether the differential activity of the MOPV and LASV replicon systems is due to cis-acting elements, MG chimeras containing 3′-UTRs, 5′-UTRs, and IGRs of the two viruses in all possible combinations were constructed. LASV MG, MOPV MG, and LASV/MOPV MG chimeras were cotransfected with expression constructs for NP and L of either LASV or MOPV. All MGs were transcriptionally active in both systems, indicating that the UTRs and IGR do not have a qualitative preference for the homologous cis- and trans-active components (Fig. 2). However, the MOPV MG was about 3-fold less active than the LASV MG, irrespective of whether NP and L protein of LASV or MOPV were used for the assay. Replacement of the MOPV 3′-UTR by that of LASV markedly increased MG activity in both systems. Despite the structural differences between the IGRs of the two viruses, replacement of this region showed only minor effects on transcriptional replicon activity. Taken together, the results indicate that cis-acting elements of LASV and MOPV S RNA can be exchanged without loss of function in the minireplicon system. The MG sequence, in particular the 3′-UTR, contributes to the reduced activity of the MOPV system compared to the LASV system.

Fig. 2.

Exchange of cis-acting elements between LASV and MOPV MGs. BSR T7/5 cells were cotransfected with LASV/MOPV MG chimeras together with wild-type NP and L protein of LASV (upper panel) or MOPV (lower panel). Transcriptional activity of the replicon systems was measured via Ren-Luc reporter gene expression. Activity of the LASV system was set at 100%. Means and standard deviations from three independent transfection experiments are shown. Compositions of the MG chimeras are indicated below the plots. In the negative control (neg), the L protein construct was replaced by empty pCITE-2a. sRLU, standardized relative light units.

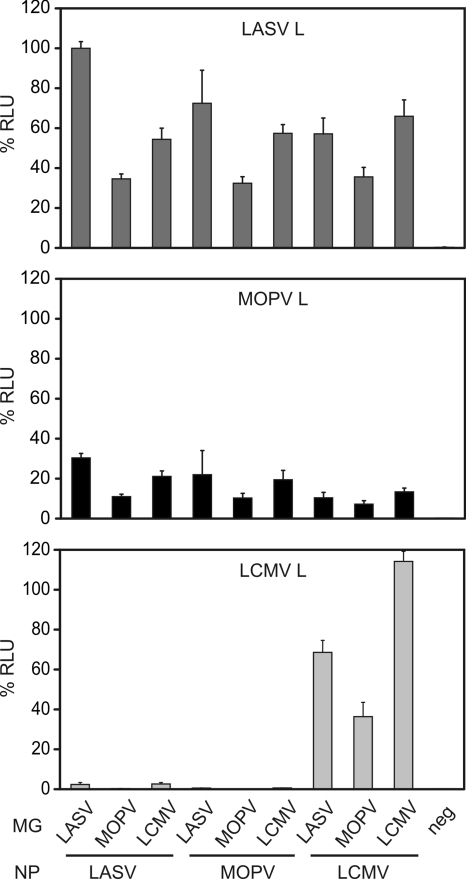

Cross-species functionality of trans-acting factors.

To determine the extent to which the trans-acting factors of the transcription machinery, that is NP and L protein, are interchangeable among LASV, MOPV, and LCMV, all possible cross-species combinations of MG, NP, and L protein were tested in the replicon systems. Transcriptional activity was measured by luciferase reporter assay. NP and L protein could be exchanged between the LASV and MOPV replicon systems without loss of function (Fig. 3, upper and middle panels). However, transcriptional activity was increased 3-fold by replacing MOPV L protein by that of LASV, irrespective of the origin of NP or MG. Exchange of NP between these two systems had no major influence. Thus, MOPV L protein rather than NP contributes to the reduced activity of the MOPV replicon system, besides the MG. The experiments with the LCMV replicon system revealed a strikingly different pattern. Replacing LCMV NP by that of LASV or MOPV led to a complete loss of function as long as the LCMV L protein was used in the experiments (Fig. 3, lower panel). This indicates that NP of LCMV displays specific features, which are missing in the NPs of LASV and MOPV, that are essential for function of LCMV L protein.

Fig. 3.

Exchange of NP, L protein, and MG among LASV, MOPV, and LCMV replicon systems. BSR T7/5 cells were cotransfected with MG and NP of LASV, MOPV, or LCMV together with L protein of LASV (upper panel), MOPV (middle panel), or LCMV (lower panel). Transcriptional activity of the replicons was measured via Ren-Luc reporter gene expression. Activity of the LASV system was set at 100%. Means and standard deviations from three independent transfection experiments are shown. In the negative control (neg), the L protein construct was replaced by empty pCITE-2a. sRLU, standardized relative light units.

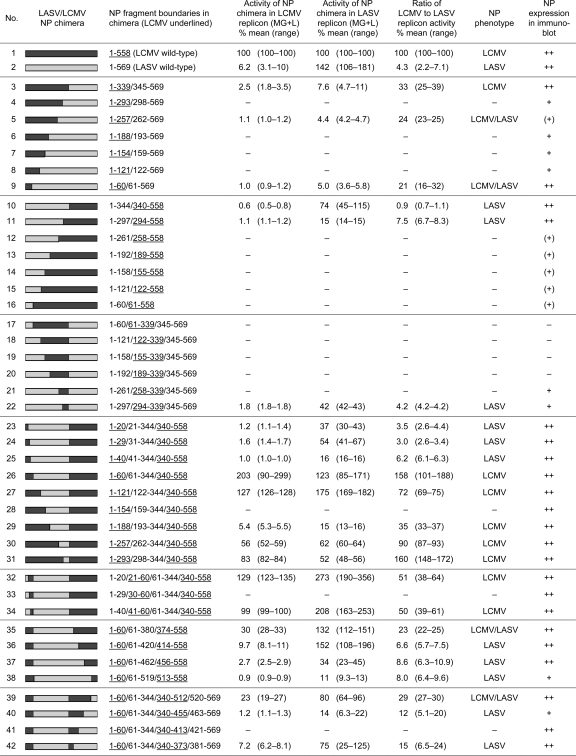

Analysis of LASV/LCMV NP chimeras.

Based on the observation that NP of LASV is active in combination with L protein of LASV but not that of LCMV, while LCMV NP is functional with both L proteins, we hypothesized that there might be specific regions in LCMV NP that are critical for functional cooperation with LCMV L protein. To map these regions, series of chimeric LASV/LCMV NP mutants were generated and analyzed in the replicon context (Fig. 4, columns 1 to 3). To avoid folding problems within the NP chimeras, fusion sites were placed in predicted loop regions. To this end, the secondary structures of the LASV and LCMV NPs were predicted by using the Jpred 3 server (10). All NPs contained a C-terminal HA tag to verify their expression in immunoblotting with an anti-HA antibody (Fig. 4, right column). Functionality of the NP chimeras was analyzed in parallel in the LASV and LCMV replicon systems. Depending on the luciferase expression values in the two systems, the NP phenotype was classified as LASV-like or LCMV-like (Fig. 4, columns 4 to 7). The phenotype was determined by measuring the ratio between the luciferase values in the LCMV versus the LASV system. An LCMV-like phenotype is characterized by comparable levels of activity of the chimera in both the LCMV and LASV replicon systems. The activity of LCMV wild-type NP in both systems and the corresponding activity ratio were set at 100% (Fig. 4, no. 1). Chimeras with a ratio of greater than 30% were considered LCMV-like. An LASV-like phenotype is characterized by low or background activity in the LCMV system but clearly measurable activity in the LASV system. The mean ratio obtained for LASV wild-type NP was 4.3% (Fig. 4, no. 2); chimeras with a ratio of between 0% and 15% were considered LASV-like. The phenotype of chimeras with an LCMV/LASV activity ratio of between 15% and 30% was defined as intermediate. Wild-type NPs of LCMV and LASV were included in each transfection experiment as controls.

Fig. 4.

Phenotype analysis of LASV/LCMV NP chimeras in replicon systems. Series of chimeric NP mutants were generated and tested in parallel in the LASV and LCMV replicon systems as described in Materials and Methods. A schematic representation of the chimeras is shown on the left, with LCMV and LASV parts depicted in dark and light gray, respectively. The NP phenotype was determined by measuring the ratio between the sRLU values in the LCMV versus the LASV system. Activity of LCMV wild-type NP was set at 100% in both systems (row 1). Accordingly, the activity ratio for LCMV wild-type NP was 1 (converted to 100% to simplify perception of the data). The limits for defining phenotypes of the chimeras were set in a proportional manner using a factor of 3.3 (upper limit, mean × 3.3; lower limit, mean/3.3). This factor covers the technical variability of the method and allows a clear discrimination between LCMV-like and LASV-like phenotypes. As LCMV wild-type NP was set at 100%, the lower limit for defining LCMV-like chimeras is 100%/3.3 = 30%. As LASV wild-type NP has a mean ratio of 4.3% (row 2), the upper limit is 3.3 × 4.3% = 15%. The phenotype of chimeras with a LCMV/LASV activity ratio of between 15% and 30% was defined as intermediate. Wild-type NPs of LCMV and LASV were included in each transfection experiment as positive controls. Means and ranges for ≥2 replicates are shown. A dash indicates that the mutant is inactive in both replicon systems. All NPs contained a C-terminal HA tag to verify their expression in immunoblotting using an anti-HA antibody. Signals on the immunoblot were quantified relative to LCMV wild-type NP (100%), and the results are given semiquantitatively on the right according to the following criteria: −, 0% to <5%; (+), 5% to <20%; +, 20% to <50%; ++, ≥50%.

In the first set of experiments (Fig. 4, chimeras no. 3 to 16), various N and C-terminal parts of LCMV and LASV NP were fused. A fusion at position 340 resulted in NPs with reduced, though measurable, activity (chimeras no. 3 and 10), with the phenotypes of these chimeras being determined by the N-terminal part. Therefore, chimeras 3 and 10 were used as a basis for further modification of the N terminus with the aim to induce a phenotype change. Replacing the N-terminal LCMV sequences in chimera no. 3 with LASV sequences led to mostly inactive mutants with poor stability as judged from the protein level in immunoblotting (Fig. 4, no. 17 to 22). However, replacement in chimera no. 10 of the N-terminal LASV sequences with LCMV sequences led to mostly stable mutants with activity in the replicon systems (Fig. 4, no. 23 to 31). Chimeras 23, 24, and 25, with up to 40 LCMV-specific N-terminal residues, still showed the LASV phenotype like the parental chimera no. 10. However, introduction of 60 or more LCMV-specific N-terminal residues completely changed the phenotype from LASV-like to LCMV-like (chimeras 26, 27, 29, 30, and 31). Thus, residues 41 to 60 appear to contain important determinants for the LCMV-like phenotype. To provide additional evidence that this region determines the phenotype, LCMV-specific residues 21 to 60, 30 to 60, and 41 to 60 were introduced into chimera 10 (Fig. 4, no. 32 to 34). The introduction of the latter sequence was sufficient to change the phenotype of chimera 10 from LASV-like to LCMV-like (chimera 34), clearly demonstrating the relevance of residues 41 to 60. To elucidate whether the LCMV-specific C terminus (positions 340 to 558) also plays a role in determining the LCMV-like phenotype, it was modified using chimera no. 26 as a basis. Any change in the C-terminal part reverted the phenotype from LCMV-like to LASV-like (Fig. 4, no. 35 to 42), indicating that positions 340 to 558 are important for the LCMV-like phenotype as well. Taken together, analyses of the chimeras revealed that residues 41 to 60 and 340 to 558 mediate the LCMV-like phenotype and that chimeric NPs containing these LCMV sequences within the LASV NP backbone are stable and fully functional in the replicon system (see chimera 34).

Amino acid residues in LCMV NP important for L protein function.

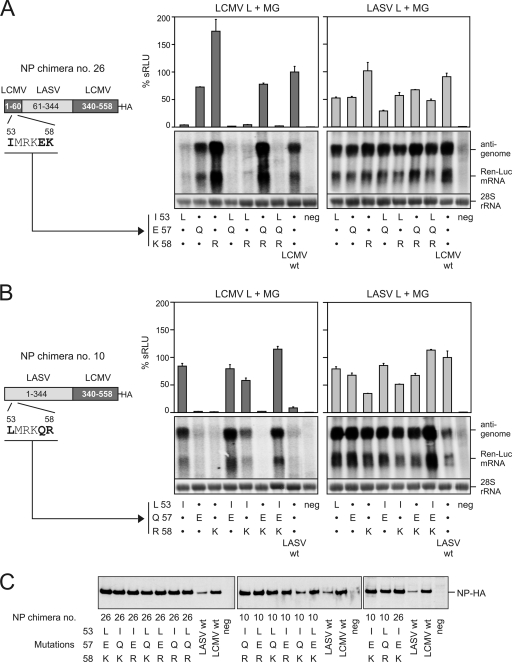

Additional experiments were set up to precisely define the amino acid residue(s) in NP that is critical for functional cooperation with LCMV L protein. The search was confined to the N-terminal region from residue 41 to 60. The C-terminal region from residue 340 to 558 was not amenable to scanning mutagenesis because of the large number of amino acid differences between LASV and LCMV. A sequence alignment of residues 41 to 60 revealed three amino acid differences between the sequences of LASV and LCMV NP used in this study (positions 53, 57, and 58) (Fig. 5). However, if all known sequences were taken into account, only the residue at position 53 consistently discriminated LASV (leucine 53) from LCMV (isoleucine 53). The residues at positions 53, 57, and 58 were exchanged individually and in all possible combinations. NP chimera 26, representing the LCMV-like phenotype, was used as a backbone for substitutions I53L, E57Q, and K58R. Reciprocal amino acid exchanges were introduced into NP chimera 10, representing the LASV-like phenotype. Activity of the NP mutants was analyzed in both the LASV and LCMV replicon systems. Ren-Luc expression was measured at 1 day posttransfection. To visualize the influence of the mutations on replication and transcription, total cellular RNA was prepared, and antigenomic RNA and Ren-Luc mRNA were detected by Northern blotting. All derivatives of chimera 26 with the LCMV-specific isoleucine at position 53 were fully competent in replication and transcription in the context of both the LCMV and LASV systems (Fig. 6A). Changing isoleucine to leucine abolished transcription and replication competence in the LCMV system, while the leucine mutants remained fully functional in the LASV system. Vice versa, all derivatives of chimera 10 with the LASV-specific leucine at position 53 were not functional in the LCMV system but were fully functional in the LASV system (Fig. 6B). Changing leucine to isoleucine restored transcription and replication competence in the LCMV system. Mutants with I53 were also functional in the LASV system. The phenotype shifts due to L53I or I53L exchanges were independent of additional mutations at positions 57 and 58. No major phenotypic changes were observed if positions 57 and 58 were changed individually. Expression of all mutant NPs was verified in immunoblotting (Fig. 6C). Taken together, these experiments demonstrate that isoleucine at position 53 of NP is essential for functional cooperation with LCMV L protein in a minireplicon assay.

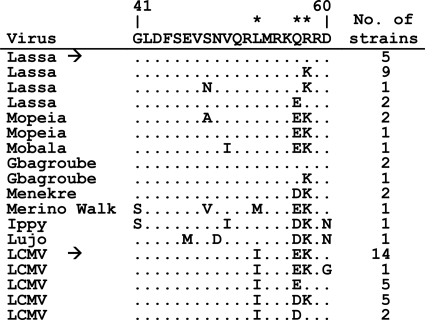

Fig. 5.

Alignment of Old World arenavirus NP sequences. The NP sequences from position 41 to 60 of all Old World arenaviruses available in the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank/index.html) by April 2011 were aligned. The sequences of the LASV and LCMV NPs used in this study are indicated by arrows. Positions differing between these two sequences are indicated by asterisks above the sequence.

Fig. 6.

Functional analysis of LASV/LCMV NP chimeras with amino acid substitutions at positions 53, 57, and 58. (A and B) Single or multiple amino acid substitutions were introduced into chimeras 26 (A) and 10 (B). A schematic representation of the parental NPs is shown at the left. The resulting mutants were tested in both the LCMV and LASV replicon systems. Transcriptional activity was measured via Ren-Luc reporter gene expression. The standardized relative light units (sRLU) are shown in the bar charts. Synthesis of antigenome and Ren-Luc mRNA was evaluated in Northern blotting (shown below the sRLU charts). Transfection and Northern blotting were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The methylene blue-stained 28S rRNA is shown below the blot as a marker for gel loading and RNA transfer. The compositions of the mutants are indicated below the diagrams. A dot indicates identity to the sequence of the parental NP chimera as shown at the left. In the negative control (neg), the L protein construct was replaced by empty pCITE-2a. (C) Expression of NP mutants. All NPs contained a C-terminal HA tag to facilitate detection by anti-HA antibody in immunoblotting. Control cells (neg) were infected with MVA-T7 but not transfected. wt, wild-type NP.

The I53L and L53I exchanges were also introduced into wild-type NPs of LCMV and LASV, respectively. The LCMV NP-I53L mutant was still active in both the LASV (69%) and LCMV (36%) replicon systems, while the LASV NP-L53I mutant was completely defective in both systems. Thus, the individual substitution of residue 53 in wild-type NP does not lead to phenotypic changes as observed in the context of the chimeric NPs. These experiments confirm the data obtained from analysis of the chimeras (Fig. 4) demonstrating that residues in the N- and C-terminal domains of NP support L protein function in a cooperative manner.

Coimmunoprecipitation studies with NP and L protein.

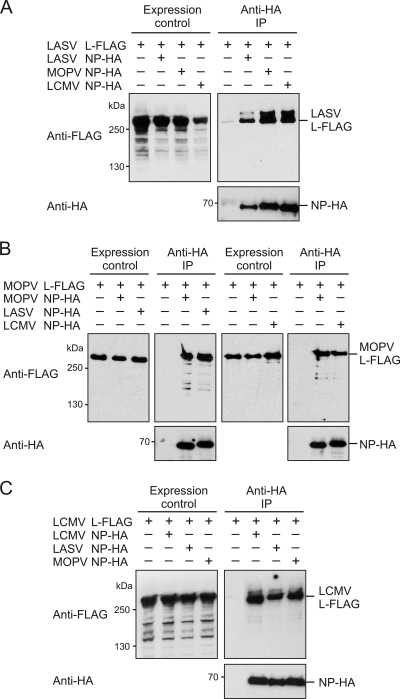

The defect of LASV and MOPV NPs in supporting LCMV L protein function in the replicon system could be due to a defect in physical NP-L protein interaction. To test this hypothesis, the interaction between homologous and heterologous NP and L proteins was studied by coimmunoprecipitation. L proteins of LASV, MOPV, and LCMV were expressed as fusion with a 3× FLAG tag, while NPs was expressed with an HA tag. Cells were cotransfected with various combinations of NP and L protein expression plasmids, and complexes were precipitated with anti-HA antibodies via the HA-tagged NP. Coimmunoprecipitated L protein was detected in immunoblotting using anti-FLAG antibodies.

LASV L protein was coprecipitated by the NPs of LASV, MOPV, and LCMV (Fig. 7A). Similarly, MOPV L protein was coprecipitated by the homologous NP as well as heterologous NPs (Fig. 7B). These results were anticipated, as L proteins of both LASV and MOPV were able to functionally interact with the heterologous NPs in the replicon system. LCMV L protein was coprecipitated by the homologous NP, as expected (Fig. 7C). However, it was also coprecipitated by the NPs of LASV and MOPV, despite the fact that these heterologous NPs do not support L protein function in the context of the replicon system. These data indicate that the defect of LASV and MOPV NPs in supporting transcriptional activity of LCMV L protein is not due to a defect in physical association of the proteins. Furthermore, the data indicate that the NP and L protein can physically interact across species boundaries.

Fig. 7.

Physical interaction between L protein and NP of LASV, MOPV, and LCMV. FLAG-tagged L protein of LASV (A), MOPV (B), or LCMV (C) was coexpressed with HA-tagged NPs of all three viruses in BHK-21/J cells. NP-L complexes were coimmunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies. Proteins in cytoplasmic lysate (expression control) and in immunoprecipitate (anti-HA IP) were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted, and detected with anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies.

DISCUSSION

This study investigated to what extent components of the replication complex of LASV, MOPV, and LCMV are able to function across species boundaries. To this end, we established a replicon system for MOPV, which exhibited lower transcriptional activity than the LASV and LCMV systems. MG, NP, and L protein could be exchanged between the replicon systems of LASV and MOPV without loss of function. The 10-fold-lower activity of the MOPV replicon system was attributable to features residing in MG and L protein of MOPV. In contrast to the case for LASV and MOPV, the LCMV L protein required the homologous NP for activity. Analysis of LASV/LCMV NP chimeras demonstrated that the LCMV-specific isoleucine residue at NP position 53 and the C-terminal region of NP spanning residues 340 to 558 are essential for function of LCMV L protein in the replicon assay. However, the defect of LASV and MOPV NP in supporting transcriptional activity of LCMV L protein is not due to a defect in physical NP-L protein interaction.

Reassortment and recombination are common mechanisms in the evolution of RNA viruses, facilitating rapid adaptation to new conditions. Reassortment, which is the exchange of complete genome segments, is common among influenza A viruses (Orthomyxoviridae). There are also examples of natural reassortment among orthobunyaviruses (3, 4, 43). So far, natural reassortants of arenaviruses have not been discovered, although there is evidence that recombination within the S RNA segment has taken place during evolution of the New World arenaviruses (8). A prerequisite for generation of a viable reassortant or recombinant virus is the compatibility of the proteins and genetic elements originating from the parental viruses. The experiments conducted here involving three important species of the Old World arenaviruses demonstrate the potential for generation of recombinant viruses within this clade. However, the range of possible recombinants may be constrained on the level of virus entry and release, which is not covered by the replicon system. Between the phylogenetically closely related LASV and MOPV, proteins and genetic elements such as UTRs and IGR could readily be exchanged without obvious loss of function. The characteristic difference between LASV and MOPV S RNA structure, the existence of two stem-loops in the IGR of MOPV (41), apparently did not affect the transcriptional activity of LASV L protein. The possibility of generating in cell culture viable MOPV/LASV reassortants containing the L RNA of MOPV and the S RNA of LASV (25) is consistent with the results obtained with the replicon systems. Another interesting observation is the reduced activity of the MOPV replicon system compared to the LASV and LCMV systems. This phenotype has been confirmed in several repeat experiments and could be attributed to L protein and MG sequences. In particular, the substitution of the MOPV 3′-UTR by that of LASV increased the expression of Ren-Luc from the MG. As the 3′-UTR lies upstream of the start codon of the Ren-Luc gene, it is conceivable that translation initiates less efficiently at the MOPV 3′-UTR than at the LASV 3′-UTR. Preliminary Northern blot data showing that the level of Ren-Luc mRNA expressed from the MOPV MG was about 60% of the level expressed from the LASV MG, while the corresponding Ren-Luc protein level as measured by luciferase assay was only 13% (unpublished data), support the hypothesis that differences in translation efficacy account at least in part for the observed differences between the two MGs.

Another factor accounting for the reduced activity of the MOPV system was L protein. Whether MOPV L protein has an intrinsically lower enzymatic activity and whether the lower pathogenicity of MOPV compared to LASV (39) is associated with the reduced replicon activity is a matter for further investigation. Rather unexpectedly, there was even the possibility of exchanging genetic elements and proteins between the African arenaviruses and the more distantly related LCMV. At least the components of the LASV and MOPV replicon systems were able to utilize MG, NP, or L protein of LCMV. However, the reciprocal experiments revealed a clear block in the functional cooperation between LCMV L protein and heterologous NPs.

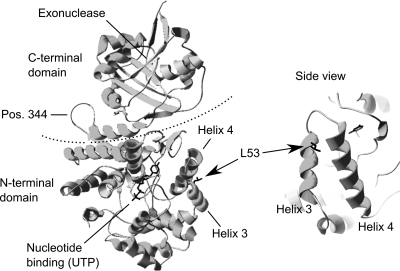

Studies on the New World arenavirus Tacaribe virus demonstrated physical association of NP and L protein (19), yet little detail is known about the interaction between the two main proteins of the arenavirus replication complex. The observation that LASV L protein is able to interact with both LASV and LCMV NPs while LCMV L protein function requires the homologous NP provided us with the unique opportunity to map residues in NP that are important for L protein function via analysis of chimeric NPs. This analysis disclosed two regions in LCMV NP that are important for the functional cooperation with the homologous L protein. Despite 38% divergence in NP amino acid sequence between LASV strain AV and LCMV Armstrong clone 13, a large number of chimeric NPs were partially or fully functional. Some of them, such as chimeras 26, 32, and 34 with the LASV/LCMV fusion site at positions 344/340, were as active as the parental wild-type proteins. The C-terminal domain of LCMV NP, spanning residues 340 to 558, has also been found to be a major determinant for function of the homologous L protein. These observations predicted the presence of functionally and structurally independent N- and C-terminal domains in NP, with the interdomain boundary being located around position 340. This prediction has been precisely confirmed by recently published X-ray crystallography studies of LASV NP (32) (Fig. 8). The second site in LCMV NP that determined the function of the homologous L protein was a single isoleucine residue at position 53. To our surprise, the very subtle change from isoleucine to leucine as found in LASV NP was sufficient to completely prevent LCMV L protein from synthesizing both antigenome and mRNA. How this residue functions during RNA synthesis is speculative. Its position on the surface of the N-terminal domain (32) (Fig. 8) suggests that it directly interacts with L protein. However, the observation that LCMV L protein physically interacts with both LCMV and LASV NP as shown by coimmunoprecipitation indicates either that the residue at position 53 is involved in only weak or temporary interaction or that several redundant sites of interaction between the proteins exist. Additional immunoprecipitation experiments performed to determine whether LCMV and LASV L proteins interact with the isolated N- or C-terminal domains of LCMV and LASV NP were not conclusive due to a low expression levels of the individual domains (data not shown).

Fig. 8.

Localization of residue 53 on the surface of the LASV NP structure. The ribbon diagram shows the X-ray structure 3MX5 (32). The side chain of L53 at the C terminus of helix 3 is shown in black. The dotted line represents the boundary between the N- and C-terminal domains.

Previously published data and our data indicate multiple interactions and functions of NP during the virus life cycle. Besides being the building block of the RNPs, NP physically interacts with other virus and cellular proteins, plays a role in budding of virus particles (7, 19, 23, 35, 36), interferes with the interferon response (27, 28), and shows exoribonuclease and nucleotide binding activity (18, 32). In particular, the C-terminal domain appears to act at various levels, specifically by interacting with L protein during RNA synthesis as shown here, by binding Z protein and the cellular transport factor ALIX/AIP1 presumably during budding (23, 35, 36), and by antagonizing interferon induction which is associated with the exoribonuclease activity (18, 27, 28, 32). These multiple functions may be regulated by phosphorylation, binding of other virus or cellular factors, or conformational changes in NP's tertiary or quaternary structure. NP of Rift Valley fever virus has recently been shown to exist in different conformations, only one of which would allow the formation of RNP complexes (11, 33).

While the experiments presented here were aimed at mapping the sites in NP that are relevant for L protein activity during RNA synthesis, future experiments may also disclose the corresponding sites on L protein. Since LASV L protein was able to function in conjunction with both LASV and LCMV NPs, while LCMV L protein was inactive with LASV NP, it may be feasible to identify regions or residues in the L proteins which determine these features by using an experimental strategy similar to that used here for the NP.

In conclusion, this study describes two regions in NP that are important for function of L protein during genome replication and transcription. The interaction between L protein and these NP sites may be a target for antiviral intervention (42). Among the Old World arenaviruses, the main components of the replication complex have the potential to functionally and physically interact across species boundaries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant GU 883/1-1 from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and grant 228292 (European Virus Archive) from the European Community. The Department of Virology of the Bernhard Nocht Institute is a WHO Collaborating Centre for Arbovirus and Haemorrhagic Fever Reference and Research (DEU-000115).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 September 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Auperin D. D., Romanowski V., Galinski M., Bishop D. H. 1984. Sequencing studies of pichinde arenavirus S RNA indicate a novel coding strategy, an ambisense viral S RNA. J. Virol. 52:897–904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Auperin D. D., Sasso D. R., McCormick J. B. 1986. Nucleotide sequence of the glycoprotein gene and intergenic region of the Lassa virus S genome RNA. Virology 154:155–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Briese T., Bird B., Kapoor V., Nichol S. T., Lipkin W. I. 2006. Batai and Ngari viruses: M segment reassortment and association with severe febrile disease outbreaks in East Africa. J. Virol. 80:5627–5630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Briese T., Kapoor V., Lipkin W. I. 2007. Natural M-segment reassortment in Potosi and Main Drain viruses: implications for the evolution of orthobunyaviruses. Arch. Virol. 152:2237–2247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brunotte L., et al. 2011. Domain structure of Lassa virus L protein. J. Virol. 85:324–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buchholz U. J., Finke S., Conzelmann K. K. 1999. Generation of bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) from cDNA: BRSV NS2 is not essential for virus replication in tissue culture, and the human RSV leader region acts as a functional BRSV genome promoter. J. Virol. 73:251–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Casabona J. C., Levingston Macleod J. M., Loureiro M. E., Gomez G. A., Lopez N. 2009. The RING domain and the L79 residue of Z protein are involved in both the rescue of nucleocapsids and the incorporation of glycoproteins into infectious chimeric arenavirus-like particles. J. Virol. 83:7029–7039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Charrel R. N., de Lamballerie X., Fulhorst C. F. 2001. The Whitewater Arroyo virus: natural evidence for genetic recombination among Tacaribe serocomplex viruses (family Arenaviridae). Virology 283:161–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Charrel R. N., de Lamballerie X., Emonet S. 2008. Phylogeny of the genus Arenavirus. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11:362–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cole C., Barber J. D., Barton G. J. 2008. The Jpred 3 secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:W197–W201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferron F., et al. 2011. The hexamer structure of the Rift Valley fever virus nucleoprotein suggests a mechanism for its assembly into ribonucleoprotein complexes. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Flatz L., Bergthaler A., de la Torre J. C., Pinschewer D. D. 2006. Recovery of an arenavirus entirely from RNA polymerase I/II-driven cDNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:4663–4668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Garcin D., Kolakofsky D. 1992. Tacaribe arenavirus RNA synthesis in vitro is primer dependent and suggests an unusual model for the initiation of genome replication. J. Virol. 66:1370–1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Günther S., Lenz O. 2004. Lassa virus. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 41:339–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hass M., Gölnitz U., Müller S., Becker-Ziaja B., Günther S. 2004. Replicon system for Lassa virus. J. Virol. 78:13793–13803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hass M., et al. 2006. Mutational analysis of the Lassa virus promoter. J. Virol. 80:12414–12419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hass M., Lelke M., Busch C., Becker-Ziaja B., Günther S. 2008. Mutational evidence for a structural model of the Lassa virus RNA polymerase domain and identification of two residues, Gly1394 and Asp1395, that are critical for transcription but not replication of the genome. J. Virol. 82:10207–10217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hastie K. M., Kimberlin C. R., Zandonatti M. A., MacRae I. J., Saphire E. O. 2011. Structure of the Lassa virus nucleoprotein reveals a dsRNA-specific 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity essential for immune suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:2396–2401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jacamo R., Lopez N., Wilda M., Franze-Fernandez M. T. 2003. Tacaribe virus Z protein interacts with the L polymerase protein to inhibit viral RNA synthesis. J. Virol. 77:10383–10393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kranzusch P. J., et al. 2010. Assembly of a functional Machupo virus polymerase complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:20069–20074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee K. J., Novella I. S., Teng M. N., Oldstone M. B., de La Torre J. C. 2000. NP and L proteins of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) are sufficient for efficient transcription and replication of LCMV genomic RNA analogs. J. Virol. 74:3470–3477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lelke M., Brunotte L., Busch C., Günther S. 2010. An N-terminal region of Lassa virus L protein plays a critical role in transcription but not replication of the virus genome. J. Virol. 84:1934–1944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levingston Macleod J. M., et al. 2011. Identification of two functional domains within the arenavirus nucleoprotein. J. Virol. 85:2012–2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lopez N., Jacamo R., Franze-Fernandez M. T. 2001. Transcription and RNA replication of Tacaribe virus genome and antigenome analogs require N and L proteins: Z protein is an inhibitor of these processes. J. Virol. 75:12241–12251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lukashevich I. S. 1992. Generation of reassortants between African arenaviruses. Virology 188:600–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lukashevich I. S., et al. 1997. The Lassa fever virus L gene: nucleotide sequence, comparison, and precipitation of a predicted 250 kDa protein with monospecific antiserum. J. Gen. Virol. 78:547–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Martinez-Sobrido L., Zuniga E. I., Rosario D., Garcia-Sastre A., de la Torre J. C. 2006. Inhibition of the type I interferon response by the nucleoprotein of the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Virol. 80:9192–9199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martinez-Sobrido L., et al. 2009. Identification of amino acid residues critical for the anti-interferon activity of the nucleoprotein of the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Virol. 83:11330–11340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morin B., et al. 2010. The N-terminal domain of the arenavirus L protein is an RNA endonuclease essential in mRNA transcription. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Perez M., Craven R. C., de la Torre J. C. 2003. The small RING finger protein Z drives arenavirus budding: implications for antiviral strategies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:12978–12983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pinschewer D. D., Perez M., de la Torre J. C. 2005. Dual role of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus intergenic region in transcription termination and virus propagation. J. Virol. 79:4519–4526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Qi X., et al. 2010. Cap binding and immune evasion revealed by Lassa nucleoprotein structure. Nature 468:779–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Raymond D. D., Piper M. E., Gerrard S. R., Smith J. L. 2010. Structure of the Rift Valley fever virus nucleocapsid protein reveals another architecture for RNA encapsidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:11769–11774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sanchez A. B., de la Torre J. C. 2005. Genetic and biochemical evidence for an oligomeric structure of the functional L polymerase of the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Virol. 79:7262–7268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shtanko O., et al. 2010. A role for the C terminus of Mopeia virus nucleoprotein in its incorporation into Z protein-induced virus-like particles. J. Virol. 84:5415–5422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shtanko O., Watanabe S., Jasenosky L. D., Watanabe T., Kawaoka Y. 2011. ALIX/AIP1 is required for NP incorporation into Mopeia virus Z-induced virus-like particles. J. Virol. 85:3631–3641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Strecker T., et al. 2003. Lassa virus Z protein is a matrix protein sufficient for the release of virus-like particles. J. Virol. 77:10700–10705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sutter G., Ohlmann M., Erfle V. 1995. Non-replicating vaccinia vector efficiently expresses bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. FEBS Lett. 371:9–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Walker D. H., et al. 1982. Experimental infection of rhesus monkeys with Lassa virus and a closely related arenavirus, Mozambique virus. J. Infect. Dis. 146:360–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wilda M., Lopez N., Casabona J. C., Franze-Fernandez M. T. 2008. Mapping of the Tacaribe arenavirus Z-protein binding sites on the L protein identified both amino acids within the putative polymerase domain and a region at the N terminus of L that are critically involved in binding. J. Virol. 82:11454–11460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wilson S. M., Clegg J. C. 1991. Sequence analysis of the S RNA of the African arenavirus Mopeia: an unusual secondary structure feature in the intergenic region. Virology 180:543–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wunderlich K., et al. 2009. Identification of a PA-binding peptide with inhibitory activity against influenza A and B virus replication. PLoS One 4:e7517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yanase T., et al. 2006. Genetic characterization of Batai virus indicates a genomic reassortment between orthobunyaviruses in nature. Arch. Virol. 151:2253–2260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]