Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the variation and trends in neuroimaging among children evaluated for minor head injury at major U.S. pediatric emergency departments (ED).

Study design

We conducted a retrospective study of children < 19 years of age with mild head injury who were evaluated and discharged home from the ED at 40 pediatric hospitals from 2005–2009 using the Pediatric Health Information Systems™ database. Variation in CT rates between hospitals was assessed for correlation with hospital specific rates of intracranial hemorrhage, admission and return visits. Age adjusted trends in CT utilization were calculated over the 5 years.

Results

Over the 5 years, the median rate of imaging for minor head injured patients was 36% [IQR 29–42%, range 19–58%]. There was no correlation between institution-specific rates of CT imaging and intracranial hemorrhage, admission or return visit rates. Age-adjusted rates of CT utilization decreased over the 5-year period on CT rates (OR 0.94 [95% CI 0.92, 0.97], p<0.001).

Conclusions

In this study, we found significant practice variation in CT utilization at pediatric hospitals evaluating children with minor head injury. These data may help guide national benchmarks for the appropriate use of CT imaging in pediatric minor head injury patients.

Keywords: Trauma, Radiology, Computed Tomography

Pediatric head trauma results in more than 650,000 emergency department (ED) visits and 64,000 hospitalizations in the United States (U.S.) every year 1. However, even though pediatric head injury is relatively common, pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI) requiring neurosurgical intervention is far less frequent 2, 3. Although pediatric TBI can be readily diagnosed with computed tomography (CT), such evaluations carry a heavy public health burden of cost and radiation exposure 4, 5. Recently, efforts have been made to develop reliable clinical decision rules for mild TBI 2, 6, 7, but it remains uncertain how these rules will impact clinical practice. Prior studies have described significant practice variation in the use of imaging after pediatric head injury, with rates ranging from 5–70% 6, 8, 9. There is some evidence to suggest that pediatric EDs have lower rates of diagnostic imaging than general EDs 10. The goal of this study was to investigate CT utilization of children with minor head injury discharged home after evaluation at pediatric hospitals.

METHODS

We used the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database, an administrative database maintained by Child Health Corporation of America (CHCA; Shawnee Mission, KS). The PHIS database (data from the National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions, Alexandria, VA) includes patient-level data from 40 hospitals that are located in 17 of the 20 major metropolitan areas in the United States and that account for more than 70% of all freestanding children’s hospitals in the United States. Participating hospitals electronically submit detailed patient data, including demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity), payer source, episode of care information (admission date, disposition, repeat hospitalization), up to 21 International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes, and resource utilization information, including imaging procedure codes, to the database. Maintaining and validating the quality of the PHIS data is a joint effort among CHCA, the participating hospitals, and Thomson Reuters (the data warehouse vendor for PHIS). Validity and reliability checks of the data are performed. Data are included in the database only when classified errors occur in less than 2% of a hospital’s quarterly data.

The study was approved by the institutional review board and the administrators of the PHIS database. In accordance with PHIS policies, the identity of the institutions will not be reported.

Study Population

Over a 5-year study period (2005–2009), we identified patient visits for minor head injury in children < 19 years discharged home from the emergency department using the ICD-9-CM codes for skull fracture (800.xx to 804.xx), concussion (850.xx), other brain injury (854.xx), and head injury not otherwise specified (959.01). Because the database does not include any clinical data, discharge from the emergency department was used as a proxy for our definition of “minor” head injury. For comparison purposes, we ascertained rates of intracranial hemorrhage (851.xx to 853.xx) for all patients (discharged and admitted) treated at the pediatric hospitals over the 5-year period. These patients were classified as having “significant” head injury.

Outcome

The primary outcome was CT imaging of the head among patients with minor head injury. The secondary outcome was a repeat ED visit within one week.

Analysis

We used simple statistics to describe the hospital specific rates of minor head injury, significant head injury and the use of diagnostic studies among patients with minor head injury. Because the decision to obtain a head CT might be balanced against admission for observation, we tested the correlation between hospital specific rate of imaging for patients with minor head injury and hospital specific admission rates for the same patient population. To test for trends of age-adjusted imaging utilization over time, we estimated logistic regression models with imaging rate as the dependent variable and year (2005 to 2009, inclusive) and categorical age as the independent variables.

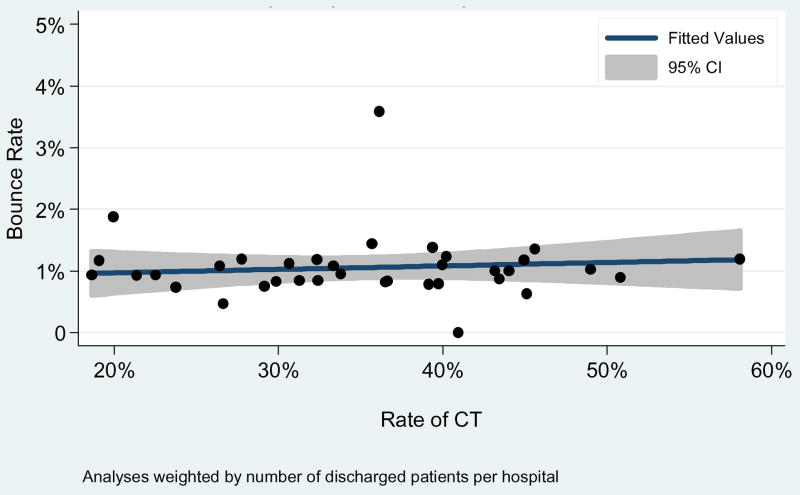

Also, for each hospital, we calculated the rate of return visits for head injury diagnoses including significant head injury within one week of an index visit, where an initial diagnosis consistent with our definition of minor heads injury was made (i.e., “bounce” rate). We estimated a linear regression model with hospital-specific bounce rate as the dependent variable and rate of imaging as the independent variable, weighted by the hospital-specific number of minor head injury patients. In this model, each hospital served as an observation (n=40), and each observation was weighted by the hospital’s total number of discharged patients. All statistical tests were two-tailed and alpha was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

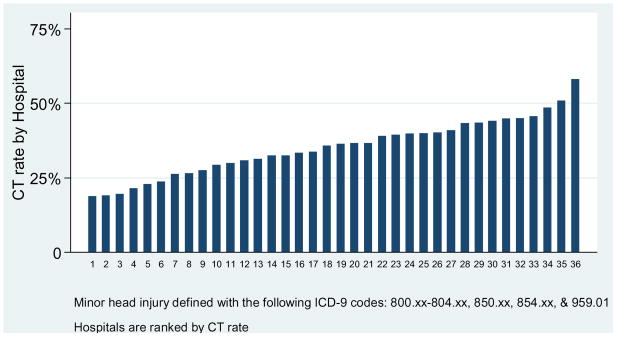

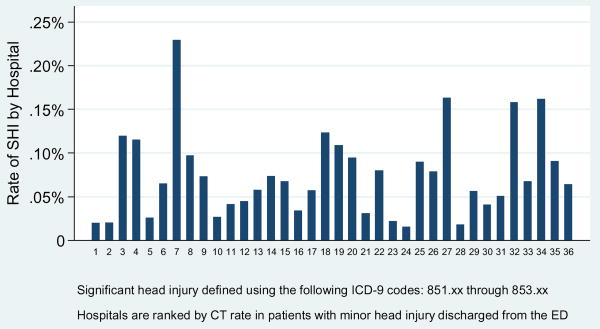

Of the 8,976,378 pediatric ED visits from 2005–2009, 161,319 (1.8%) were discharged home with minor head injury, and 6,494 (0.07%) where diagnosed with significant head injury. Hospital specific rates of minor head injury and significant head injury ranged from 0% to 3.1% and 0.02% to 1.03%, respectively (Table I; available at www.jpeds.com). Over the 5 years, the median rate of imaging for minor head injured patients was 36% (IQR 29–42%, range 19–58%; Figure 1). The hospital specific rate of imaging for minor head injured patients was not associated with hospital specific admission rates for the same patient population (r=−0.06, p=0.71). There was no significant association between institution specific rates of significant head injury patients and the rate of CT utilization among minor head injury patients (r=0.13, p=0.44, weighted by total ED volume per hospital)(Figure 2) nor was there an association between institution specific CT rates among minor head injury patients and return visits within a week after initial assessment (r=0.10, p=0.55, weighted by total ED volume per hospital)(Figure 3).

Table 1.

Imaging studies of patients presenting to the ED with head injury across a sample of pediatric hospitals in the US, 2005–2009

| Hospital | Total ED visits | Minor head injury cases discharged from the ED | Percent of all ED visits(95% CI) | Significant head injury cases | Percent of all ED visits (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 199602 | 5011 | 2.5% | (2.4, 2.6) | 247 | 0.12% | (0.11, 0.14) |

| B | 284008 | 7442 | 2.6% | (2.6, 2.7) | 329 | 0.12% | (0.10, 0.13) |

| C | 274658 | 4603 | 1.7% | (1.6, 1.7) | 261 | 0.10% | (0.08, 0.11) |

| D | 322018 | 4432 | 1.4% | (1.3, 1.4) | 219 | 0.07% | (0.06, 0.08) |

| E | 330343 | 5652 | 1.7% | (1.7, 1.8) | 216 | 0.07% | (0.06, 0.07) |

| F | 313778 | 9602 | 3.1% | (3.0, 3.1) | 283 | 0.09% | (0.08, 0.10) |

| G | 290684 | 4350 | 1.5% | (1.5, 1.5) | 169 | 0.06% | (0.05, 0.07) |

| H | 297695 | 8075 | 2.7% | (2.7, 2.8) | 171 | 0.06% | (0.05, 0.07) |

| I | 269001 | 4656 | 1.7% | (1.7, 1.8) | 138 | 0.05% | (0.04, 0.06) |

| J | 218177 | 3311 | 1.5% | (1.5, 1.6) | 75 | 0.03% | (0.03, 0.04) |

| K | 177998 | 3517 | 2.0% | (1.9, 2.0) | 162 | 0.09% | (0.08, 0.11) |

| L | 202541 | 3338 | 1.6% | (1.6, 1.7) | 221 | 0.11% | (0.09, 0.12) |

| M | 234411 | 3314 | 1.4% | (1.4, 1.5) | 52 | 0.02% | (0.02, 0.03) |

| N | 186536 | 1829 | 1.0% | (.9, 1.0) | 77 | 0.04% | (0.03, 0.05) |

| O | 420750 | 4699 | 1.1% | (1.1, 1.1) | 110 | 0.03% | (0.02, 0.03) |

| P | 388803 | 6542 | 1.7% | (1.6, 1.7) | 176 | 0.05% | (0.04, 0.05) |

| Q | 377602 | 6063 | 1.6% | (1.6, 1.6) | 244 | 0.06% | (0.06, 0.07) |

| R | 208125 | 3085 | 1.5% | (1.4, 1.5) | 56 | 0.03% | (0.02, 0.03) |

| S | 238032 | 5603 | 2.4% | (2.3, 2.4) | 135 | 0.06% | (0.05, 0.07) |

| T | 125730 | 1534 | 1.2% | (1.2, 1.3) | 23 | 0.02% | (0.01, 0.03) |

| U | 298005 | 4259 | 1.4% | (1.4, 1.5) | 239 | 0.08% | (0.07, 0.09) |

| V | 83870 | 295 | 0.4% | (0.3, 0.4) | 137 | 0.16% | (0.14, 0.19) |

| W | 494824 | 9159 | 1.9% | (1.8, 1.9) | 207 | 0.04% | (0.04, 0.05) |

| X | 263864 | 3774 | 1.4% | (1.4, 1.5) | 195 | 0.07% | (0.06, 0.08) |

| Y | 23144 | 0 | 0 | n/a | 139 | 0.6% | (0.50, 0.70) |

| Z | 563328 | 14569 | 2.6% | (2.5, 2.6) | 382 | 0.07% | (0.06, 0.07) |

| AA | 169992 | 3998 | 2.4% | (2.3, 2.4) | 35 | 0.02% | (0.01, 0.03) |

| BB | 76584 | 216 | 0.3% | (0.2, 0.3) | 176 | 0.23% | (0.20, 0.26) |

| CC | 400851 | 11479 | 2.9% | (2.8, 2.9) | 125 | 0.03% | (0.03, 0.04) |

| DD | 65788 | 270 | 0.4% | (0.4, 0.5) | 79 | 0.12% | (0.09, 0.15) |

| EE | 199023 | 4974 | 2.5% | (2.4, 2.6) | 315 | 0.16% | (0.14, 0.18) |

| FF | 74241 | 1087 | 1.5% | (1.4, 1.6) | 15 | 0.02% | (0.01, 0.03) |

| GG | 411915 | 4446 | 1.1% | (1.0, 1.1) | 326 | 0.08% | (0.07, 0.09) |

| HH | 210653 | 1783 | 0.8% | (0.8, 0.9) | 155 | 0.07% | (0.06, 0.09) |

| II | 43180 | 298 | 0.7% | (0.6, 0.8) | 70 | 0.16% | (0.12, 0.20) |

| JJ | 155434 | 3673 | 2.4% | (2.3, 2.4) | 152 | 0.10% | (0.08, 0.11) |

| KK | 27691 | 0 | 0 | n/a | 108 | 0.39% | (0.32, 0.46) |

| LL | 11619 | 0 | 0 | n/a | 34 | 0.29% | (0.19, 0.39) |

| MM | 23065 | 0 | 0 | n/a | 238 | 1.03% | (0.90, 1.16) |

| NN | 18815 | 381 | 2.0% | (1.8, 2.2) | 3 | 0.02% | (0.00, 0.03) |

|

| |||||||

| Summary1 | 8,976,378 | 161,319 | 1.8% | (1.79, 1.81) | 6,494 | 0.072% (0.071, 0.074) | |

Head injury defined using the following ICD-9 codes: 800.xx-804.xx, 850.xx-854.xx, and 959.01 Significant head injury defined using the following ICD-9 codes: 851.xx-853.xx

Values represent the sum over all hospitals

Figure 1.

Rates of CT in pediatric patients with minor head injury discharged from the ED (n=161,319), across a sample of pediatric hospitals in the US from 2005–2009

Figure 2.

Significant head injury (SHI) as a proportion of all ED visits across a sample of pediatric hospitals in the US from 2005–2009

Figure 3.

Association between rates of imaging of pediatric patients discharged from the ED with minor head injury (n=159,322) and rates of subsequent ED visits across a sample of pediatric hospitals in the U.S., 2005–2009

Rates of imaging were greatest in teenagers (48% for teenagers compared with 35% in infants, 28% in preschool children and 37% in school aged children) (Table II). Age-adjusted rates of CT decreased over the study time period (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 0.94 (95% CI 0.92, 0.97), test of linear trend p<0.001) but there was no evidence that the association between rates of CT and year differed by age (p=0.401).

Table 2.

Rates of imaging studies in pediatric patients with minor head injury discharged from the ED (n=161,319) across a sample of pediatric hospitals in the US from 2005–2009, stratified by age

| Rate (95% Confidence Interval) of CT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | Total | |

| <1 year | 35.4% (33.9, 36.9) | 37.9% (36.5, 39.3) | 35.8% (34.5, 37.1) | 35.1% (33.8, 36.3) | 32.2% (31.1, 33.4) | 35.0% (34.4, 35.6) |

| 1–5 years | 28.5% (27.6, 29.4) | 30.3% (29.4, 31.2) | 29.4% (28.6, 30.2) | 27.1% (26.4, 27.9) | 24.7% (24.1, 25.4) | 27.6% (27.3, 28.0) |

| 6–11 years | 39.6% (38.3, 41.0) | 39.9% (38.6, 41.2) | 39.5% (38.4, 40.7) | 37.2% (36.1, 38.4) | 33.3% (32.4, 34.3) | 37.4% (36.9, 37.9) |

| ≥12 years | 49.2% (47.8, 50.6) | 49.8% (48.5, 51.0) | 50.0% (48.8, 51.2) | 47.4% (46.2, 48.6) | 44.7% (43.7, 45.7) | 47.9% (47.3, 48.4) |

|

| ||||||

| Total 1 | 36.5% (35.9, 37.1) | 38.0% (37.4, 38.6) | 37.2% (36.6, 37.7) | 35.0% (34.5, 35.5) | 32.1% (31.7, 32.5) | 35.4% (35.1, 35.6) |

Minor head injury defined using the following ICD-9 codes: 800.xx-804.xx, 850.xx, 854.xx, and 959.01

Test for linear trend of time on CT rates, adjusting for age: OR (95% CI) = 0.94 (0.92, 0.97), p<0.001

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that there is significant variation in rates of CT after minor head injury in children, even among major pediatric emergency departments. Although mild head injury is frequent in children, there is still controversy and variability in the use of neuroimaging for head injury. This is the first large scale study to demonstrate variability and recent trends in CT utilization for minor head injury at major U.S. pediatric emergency departments.

Unlike prior studies looking at overall rates of CT use, we found a trend to decreased age-adjusted head CT utilization with over the 5 years of our study 8, 11. Although not studied, possible explanations for this encouraging trend may be heightened awareness of the potential long-term consequences of radiation exposure and the adoption of more judicious recommendations supported by recent decision rules 2, 3, 7. In this regard, our findings are similar to those of prior studies, which demonstrate lower rates of imaging at pediatric versus general emergency departments 8, 10. The rates found in our study are similar to those reported by Kuppermann et al, who found in a large prospective cohort that 35.3% of pediatric patients with mild TBI undergo head imaging 2. The data in our study may be useful for national benchmarking of CT utilization for minor head injury.

However, our study shows that there is still significant improvement to be made, even at pediatric institutions. We found that despite relatively low rates of identified intracranial hemorrhage, CT rates of minor head injury patients at pediatric hospitals ranged from 19 to 58%. This type of variation in management has been described in pediatric emergency departments compared with general emergency departments. Until now, however, such variation has not been described between pediatric emergency departments themselves. It is unclear how hospital specific factors, such as case mix, relate to this variability. The rates of intracranial hemorrhage do not appear to correlate with the rates of imaging across institutions.

Another area for improvement is in the imaging of teenagers. It is unclear why neuroimaging is increased in this age group, even after controlling for injury severity by analyzing only discharged patients with presumed minor head injury. We hypothesize that ease of imaging in the teenage population (i.e., lack of need for sedation or restraint) may explain part of this phenomenon. The mechanisms of injury in this age group may be more concerning, which may also influence the decision to obtain a head CT.

Our study has several limitations. First, data are limited to tertiary-care, freestanding children’s hospitals that are part of the PHIS system. Thus, our conclusions may not be generalizable to other academic or community hospitals. However, given the variability described in prior studies of head CT utilization in pediatric head injury, this small subset of hospitals likely provides important data for national benchmarks. Second, there may be important confounders that influence the variability of imaging rates in the PHIS hospitals, although we can only speculate on the nature of these confounders. Third, our diagnosis classifications rely on the ICD-9-CM coding system, which has the potential for inaccuracy. Fourth, our definition of minor head injury (based on discharge from ED) should not be equated with other clinical studies that use mechanisms of injury or neurologic findings or scores to classify the head injury as minor. However, we believe this definition of mild is more conservative than those utilized in recent studies clinical studies which also include admitted patients. Although our definition of TBI may significantly underestimate the proportion of mild TBI patients who both undergo CT evaluation and who have findings on CT, in the absence of clinical measures, we feel our approach is most conservative and avoids misclassifying patients as mild TBI who in fact had more significant injuries. Fifth, although we looked at return visit rates to the PHIS hospitals, we do not have data as to whether patients went to other hospitals for a second visit. However, the PHIS hospitals represent the major pediatric centers for many regions and therefore are more likely the referral centers for neurosurgical emergencies, even if the child was initially seen at a different local hospital. Finally, the database does not include clinical outcome. Therefore, we were unable to demonstrate the impact of imaging on head injury outcomes. However, by limiting our analysis to discharged patients, we suspect that outcomes were not fundamentally altered by the use of advanced imaging in this subset of pediatric head injury patients.

Acknowledgments

Supported by K12 HD052896-01A1 (to R.M.) and NIH T32 HD040128-06A1(to W.M.).

Abbreviations

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

- CT

computed tomography

- ED

emergency department

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kuppermann N. Pediatric head trauma: the evidence regarding indications for emergent neuroimaging. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38 (Suppl 4):S670–674. doi: 10.1007/s00247-008-0996-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, Hoyle JD, Jr, Atabaki SM, Holubkov R, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374(9696):1160–1170. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61558-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palchak MJ, Holmes JF, Vance CW, Gelber RE, Schauer BA, Harrison MJ, et al. A decision rule for identifying children at low risk for brain injuries after blunt head trauma. Ann of Emerg Med. 2003;42:492–506. doi: 10.1067/s0196-0644(03)00425-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner D, Elliston C, Hall E, Berdon W. Estimated risks of radiation-induced fatal cancer from pediatric CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176(2):289–296. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.2.1760289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner DJ. Estimating cancer risks from pediatric CT: going from the qualitative to the quantitative. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32(4):228–223. doi: 10.1007/s00247-002-0671-1. discussion 242–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maguire JL, Boutis K, Uleryk EM, Laupacis A, Parkin PC. Should a head-injured child receive a head CT scan? A systematic review of clinical prediction rules. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):e145–154. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atabaki SM, Stiell IG, Bazarian JJ, Sadow KE, Vu TT, Camarca MA, et al. A clinical decision rule for cranial computed tomography in minor pediatric head trauma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(5):439–445. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.5.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blackwell CD, Gorelick M, Holmes JF, Bandyopadhyay S, Kuppermann N. Pediatric head trauma: changes in use of computed tomography in emergency departments in the United States over time. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(3):320–324. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klassen TP, Reed MH, Stiell IG, Nijssen-Jordan C, Tenenbein M, Joubert G, et al. Variation in utilization of computed tomography scanning for the investigation of minor head trauma in children: a Canadian experience. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(7):739–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mannix R, Bourgeois FT, Schutzman SA, Bernstein A, Lee LK. Neuroimaging for pediatric head trauma: do patient and hospital characteristics influence who gets imaged? Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(7):694–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korley FK, Pham JC, Kirsch TD. Use of advanced radiology during visits to US emergency departments for injury-related conditions, 1998–2007. JAMA. 2010;304(13):1465–1471. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]