Abstract

Introduction

In 2005, the American Heart Association (AHA) released guidelines to improve survival rates from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA).

Objective

To determine if, and when, emergency medical services (EMS) agencies participating in the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (ROC) implemented these guidelines.

Methods

We contacted 178 EMS agencies and completed structured telephone interviews with 176 agencies. The survey collected data on specific treatment protocols before and after implementation of the 2005 guidelines as well as the date of implementation crossover (the “crossover date”). The crossover date was then linked to a database describing the size, type, and structure of each agency. Descriptive statistics and regression were used to examine patterns in time to crossover.

Results

The 2005 guidelines were implemented by 174 agencies (99%). The number of days from guideline release to implementation was as follows: mean 416 (standard deviation 172), median 415 (range 49–750). There was no difference in time to implementation in fire-based agencies (mean 432), nonfire municipal agencies (mean 365), and private agencies (mean 389, p = 0.31). Agencies not providing transport took longer to implement than agencies that transported patients (463 vs. 384 days, p = 0.004). Agencies providing only basic life support (BLS) care took longer to implement than agencies who provided advanced life support (ALS) care (mean 462 vs. 397 days, p = 0.03). Larger agencies (>10 vehicles) were able to implement the guidelines more quickly than smaller agencies (mean 386 vs. 442 days, p = 0.03). On average, it took 8.9 fewer days to implement the guidelines for every 50% increase in EMS-treated runs/year to which an agency responded.

Conclusion

ROC EMS agencies required an average of 416 days to implement the 2005 AHA guidelines for OHCA. Small EMS agencies, BLS-only agencies, and nontransport agencies took longer than large agencies, agencies providing ALS care, and transport agencies, respectively, to implement the guidelines. Causes of delays to guideline implementation and effective methods for rapid EMS knowledge translation deserve investigation.

Keywords: heart arrest, emergency medical services, knowledge translation, prehospital care, guidelines, implementation

Introduction

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is common and deadly.1 It is estimated that more than 300,000 people suffer from OHCA each year in the United States, with a survival rate of approximately 8%.1 To guide emergency providers in the treatment of OHCA, the American Heart Association (AHA) releases evidence-based guidelines derived from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation Consensus on Science and Treatment Recommendations. On December 13, 2005, the AHA published “Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care” for use by emergency medical services (EMS),2 with the goal that application of these guidelines will improve outcomes.3,4 The Utstein statement on survival suggests that science, education, and implementation interact to affect survival from cardiac arrest.5

It has been estimated that only 55% of patients in the United States receive medical care adhering to scientific evidence-based guidelines.6 Further, it is thought that cancer outcomes could improve 30% if current knowledge were consistently applied,7 reducing mortality by up to 10%.8 Research suggests that best practices are not always implemented. Four studies have described delays to the implementation of therapeutic hypothermia for patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest despite recommendations from the AHA.9–12 Another study demonstrated that fewer than 30% of EMS providers were aware of pediatric defibrillation guidelines and only one third had access to pediatric defibrillation pads.13

Very little knowledge-translation research has been conducted in the out-of-hospital setting.14 We sought to determine whether EMS implemented the 2005 AHA cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiac care (ECC) guidelines, and when this implementation occurred. We examined characteristics of EMS agencies that were associated with faster implementation.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (ROC) consists of 10 clinical centers covering 11 regions across North America and was created to study OHCA and life-threatening trauma.15 Three of the regions are Canadian and eight are American. These 10 centers have 264 separate EMS agencies participating in a population-based registry and clinical trials. We excluded two sites because their EMS agencies were employing cardiac arrest protocols similar to the 2005 guidelines prior to the release of the guidelines. We also excluded air transport agencies that did not primarily respond to 9-1-1 calls. We invited 178 EMS agencies in the remaining eight centers to participate in a brief telephone survey regarding implementation of the cardiac arrest guidelines. Data from the ROC Epistry database were used with research ethics board (REB) approval (No. 435–2005). Additional descriptive/infrastructure data were obtained using a telephone survey methodology not considered part of human subject research and not requiring REB approval under the directing REB. Verbal consent was obtained and no compensation or incentives were offered to respondents.

Survey Methodology

A structured telephone survey was developed using the Total Design Method.16 Representatives from each ROC center participated in the selection of questions for the survey. The survey was pilot tested using non-ROC agencies prior to being administered. A data dictionary was compiled to manage dissimilar regional terminology and to ensure clarity when administering the survey. The principal investigator from each ROC site was asked to send a letter to each agency introducing the survey and the rationale in an effort to engage the potential respondents. The survey was administered during a five-month period from November 2007 to March 2008 by the principal investigator (BLB) and a research assistant who was trained at a dedicated training session by the principal investigator. Responses were recorded by the interviewer by checking boxes or filling in fields with standard formats.

Respondents were asked to provide implementation dates that best reflected when all providers were utilizing new guidelines in the field. Most agencies reported a “go-live” date on which new protocols came into effect, whereas some reported the end of a “rolling start” period during which some providers were utilizing new protocols while untrained providers were using old protocols. Standard of care prior to the adoption of the 2005 guidelines was established using seven questions. Implementation of key components of the 2005 guidelines was then established using eight questions. These key features included immediate CPR as opposed to immediate analysis, single defibrillation attempts as opposed to three stacked shocks, 2 minutes of CPR between each defibrillation attempt, rather than 1 minute, and placing an emphasis on CPR quality, including rate and depth of compressions, complete chest recoil, minimizing interruptions, and avoiding hyperventilation.

Definition of Crossover Time

We measured the crossover date from the date on which the guidelines were published in print, December 13, 2005, to the date an agency reported that comprehensive implementation of the 2005 AHA guidelines for CPR and ECC had occurred (either the go-live date or the end of a rolling start). When the agency chose not to implement 2 minutes of chest compressions before analysis in unwitnessed cardiac arrest, we accepted the date of all other guideline components as the crossover date. We conservatively chose the first day of the month when only a month was given by the respondent.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present the primary results. Measures of central tendency (mean and median) and measures of dispersion (range and standard deviation) were described for crossover time. A priori comparisons sought to explain variation in the number of days to crossover. We chose to compare three measures of agency size and three descriptions of agency type because they could potentially affect the implementation of guidelines. For agency size, annual call volume, number of vehicles as a proxy measure for the number of defibrillators requiring software reprogramming, and total number of providers who would require training were examined. For type of EMS system, we included care level (advanced life support [ALS] or basic life support [BLS]), transport capability (yes/no), and organizational structure (fire-based service, government nonfire service, or private service). These data were available for each agency using the ROC EMS Structures Database, which houses agency responses to a “structures survey,” and was consistent with data from previous ROC publications.15

Descriptive statistics are presented for all variables. For testing we used Bonferroni-corrected two-sample t-tests, one-way analysis of variance testing, and linear regression. Assumptions for these tests were assessed using graphs. An alpha of 0.05 was considered statistically significant; no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. The data analysis for this paper was generated using SAS software, version 9.1 of the SAS System for Windows (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

The survey was completed by 176 of 178 agencies (response rate of 99%). One agency refused to complete the survey, citing “not enough time.” One agency was unable to obtain the information required. Two agencies had not crossed over when surveyed at the end of the survey period in March 2008. Thus, 174 agencies were included in the final analysis (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of the ROC Agencies (n = 174).

| n(%) | |

|---|---|

| Organizational structure | |

| Fire department | 118 (69%) |

| Governmental, nonfire | 27 (16%) |

| Private, nonhospital | 12 (7%) |

| Other | 14 (8%) |

| Missing | 3 (2%) |

| Number of vehicles | |

| 1–5 | 53 (31%) |

| 6–10 | 39 (23%) |

| 11–50 | 70 (41%) |

| 51+ | 10 (6%) |

| Missing | 2 (1%) |

| Service | |

| ALS/BLS | 122 (71%) |

| BLS only | 50 (29%) |

| Missing | 2 (1%) |

The characteristics of the included agencies were obtained from the ROC EMS Structures Database, which houses the responses to a “structures survey” that each EMS agency submitted at the start of the consortium.

ALS = advanced life support; BLS = basic life support; EMS = emergency medical services; ROC = Research Outcomes Consortium.

All included ROC EMS agencies were previously adhering to the 2000 AHA guidelines. The 2005 guidelines were subsequently implemented by 174 of 176 (99%) of the agencies. The remaining 1% intended to implement the 2005 guidelines in the near future. The mean number of days from guideline release to guideline implementation was 416 days (standard deviation [SD] 172 days) and the median was 415 days (range: 49 to 750 days) (Figs. 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Boxplot showing the number of days from guideline release to guideline implementation (crossover time). The white box represents one standard deviation (172 days). The mean is 416 days; the median is 415 (range: 49 to 750 days).

Figure 2.

Variation in the length of time required to implement the 2005 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines in 176 emergency medical services (EMS) agencies.

We examined agency size in relation to crossover time and found that larger agencies implemented the guidelines more quickly than smaller agencies. Agencies with more than 10 vehicles implemented the guidelines faster than agencies with 10 or fewer vehicles (386 days vs. 442 days, p = 0.03). For every 50% increase in EMS-treated runs per year, it took an average of 8.9 fewer days to implement the 2005 guidelines (p = 0.01); however, these data were heavily skewed by a small number of large-volume agencies (Fig. 3). The number of staff employed by an agency did not significantly affect crossover time.

Figure 3.

The y-axis is crossover time and the x-axis is emergency medical services (EMS)-treated runs per year. The line of best fit shows that for every 50% increase in EMS-treated runs per year, crossover time decreases by 8.9 days (p = 0.01). The data are skewed by a small number of agencies with a high number of runs per year.

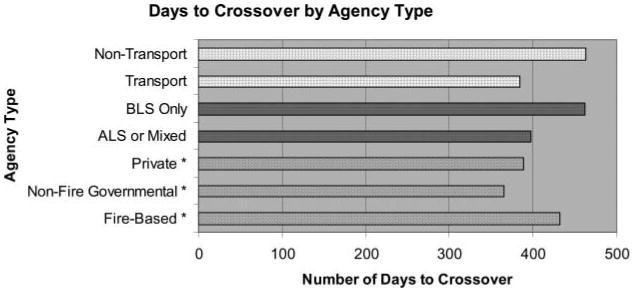

Examination of agency type identified no statistically significant difference in implementation time between fire-based agencies, nonfire governmental agencies, and private agencies (432, 365, and 389 days, respectively, p = 0.31). Agencies that provided only BLS services required longer to implement the guidelines than did agencies that provided all-ALS or mixed ALS/BLS services (462 days vs. 397 days, respectively, p = 0.03). Agencies that did not transport patients required more days to implement the guidelines than did agencies that transported patients (463 days vs. 384 days, respectively, p = 0.004) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Days to crossover are presented for various types of emergency medical services (EMS) agencies including transport/nontransport, basic life support (BLS)/advanced life support (ALS), and organizational structure (private/nonfire governmental/fire-based). *p-Value not significant.

Discussion

The 2005 guidelines were published on December 13, 2005, and, by March 2008, 99% of the ROC EMS agencies had implemented the new guidelines, with a mean time delay of 416 days (SD 172 days). The length of time required to implement the 2005 AHA guidelines in EMS agencies was highly variable, ranging from 49 to 750 days. Some EMS agencies were able to implement the guidelines in less than two months; others took over two years. There may be EMS system factors that facilitated prompt knowledge translation as well as factors acting as barriers to rapid implementation of guidelines.

Larger agencies might be thought to require more time to train their providers in new guidelines and update equipment. However, this study found the opposite. Smaller agencies required more time to implement the guidelines than did larger agencies. Large agencies may have been able to implement the guidelines more quickly because of educational commitment and supportive infrastructure. Medical oversight in large agencies may focus on providing the latest medical directives, have established training departments and personnel, and have more experienced administrators when compared with smaller agencies. Smaller agencies may have less staff, no committed training personnel, and smaller budgets. Medical directors, regulators, and EMS administrators have the opportunity to be opinion leaders and agents of change and should maximize their position to enhance knowledge translation.

Formal training departments, common to larger agencies, often have special training facilities, dedicated educators, and relatively frequent training cycles. These advantages may have allowed for more timely training and quicker implementation of guidelines.

Defibrillation and other electrical therapies were changed in the 2005 guidelines.2 Modern defibrillators have software algorithms that aid and guide rescuers in care. As such, it is important that defibrillator software be easily upgradable to reflect current guidelines. Following the release of the 2005 guidelines, defibrillator software upgrades were delayed because of the complexity of the processes required. Industry partners and regulators, such as the Food and Drug Administration or Health Canada, play a role in guideline implementation. This barrier to rapid implementation may have been accentuated in smaller agencies because of lack of dedicated information technology support staff or access to capital funds.

The release dates of future guidelines should be advertised well ahead of their publication to allow EMS agencies to anticipate practice changes and should include implementation targets for these agencies to strive to meet. Effective implementation strategies, from marketing to incentives to tricks and tools, are an essential consideration when new clinical practice guidelines are released to improve the translation of knowledge into field practice and require urgent research and application to EMS settings.

Limitations

This telephone survey is limited by both self-reporting bias and recall bias. To address these biases, we used a standard survey tool, administered over the phone, allowed respondents the opportunity to postpone responses, and gave them advance notice of the phone call. We contacted all ROC agencies15 in the included sites; however, these agencies may not be generalizable to all EMS systems and many of the medical directors overseeing these sites are affiliated with academic health sciences centers, were involved in the guideline process, and had advanced knowledge prior the release date measured in this study. Further, we excluded two agencies that had not yet adopted the guidelines. These factors make it possible that non-ROC EMS agencies had delays to implementation that were greater than those we report. These limitations should be considered in the context of the many strengths of this study, including the population-based approach and the high level of survey completion.

Conclusion

The ROC EMS agencies required an average of 416 days (SD 172 days) to implement the 2005 AHA guidelines for OHCA. Small EMS agencies, BLS-only agencies, nontransport agencies, and fire-based agencies took longer than large agencies, agencies providing ALS care, transport agencies, and nonfire agencies, respectively, to implement the guidelines. Causes of EMS delays to guideline implementation and effective methods for rapid EMS knowledge translation deserve investigation.

Acknowledgments

The ROC is supported by a series of cooperative agreements to 10 regional clinical centers and one data coordinating center (5U01, HL077863, HL077881, HL077871, HL077872, HL077866, HL077908, HL077867, HL077885, HL077887, HL077873, and HL077865) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in partnership with the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, U.S. Army Medical Research & Material Command, The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)–Institute of Circulatory and Respiratory Health, Defense Research and Development Canada, the American Heart Association, and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.

We would like to thank the paramedics and first responders in the EMS agencies participating in this study. We are grateful to the EMS managers who donated their time to complete the study survey.

Footnotes

The ROC investigators can be found at https://roc.uwctc.org

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, with regard to the article.

References

- 1.Nichol G, Thomas E, Callaway CW, et al. Regional variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome. JAMA. 2008;300:1423–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.12.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2005;112(24 suppl):IV1–203. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.166550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anonymous. American Heart Association Guidelines for CPR and ECC. Part 1. Introduction. Circulation. 2005;112(22 suppl):III-1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anonymous. American Heart Association 2005 Guidelines for CPR and ECC. Part 3. Overview of CPR. Circulation. 2005;112(24 suppl):IV-12–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laerdal Foundation for Acute Medicine. [Accessed July 15, 2009];Utstein. Available at: http://www.laerdalfoundation.org/studier_hypoteser.html.

- 6.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canadian Cancer Control Strategy. Canadian strategy for cancer control. Synthesis report. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford L, Kalunzy A, Sondik E. Diffusion and adoption of state of the art therapy. Semin Oncol. 1990;4:485–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abella BS, Rhee JW, Huang KN, Vanden Hoek TL, Becker LB. Induced hypothermia is underused after resuscitation from cardiac arrest: a current practice survey. Resuscitation. 2005;64:181–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merchant R, Soar J, Skrifvars M, et al. Therapeutic hypothermia utilization among physicians after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2006;24:1935–40. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000220494.90290.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennedy J, Green R, Stenstrom R. The use of induced hypothermia after cardiac arrest: a survey of Canadian emergency physicians. Can J Emerg Med. 2008;10:125–30. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500009830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bigham BL, Dainty KN, Scales DC, Morrison LJ, Brooks SC. Predictors of adopting therapeutic hypothermia for post-cardiac arrest patients among Canadian emergency and critical care physicians. Resuscitation. 2010 Jan;81(1):20–4. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haskell SE, Kenney MA, Patel S, et al. Awareness of guidelines for use of automated external defibrillators in children within emergency medical services. Resuscitation. 2008;76:354–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cone DC. Knowledge translation in the emergency medical services: a research agenda for advancing prehospital care. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:1052–7. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis DP, Garberson LA, Andrusiek DL, et al. A descriptive analysis of emergency medical service systems participating in the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (ROC) network. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2007;11:369–82. doi: 10.1080/10903120701537147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dillman DA. Mail and telephone surveys: the Total Design Method. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1978. [Google Scholar]