Abstract

The ventral tegmental area (VTA) is thought to play an important role in reward function. Two populations of neurons, containing either dopamine (DA) or γ-amino butyric acid (GABA), have been extensively characterized in this area. However, recent electrophysiological studies are consistent with the notion that neurons that utilize neurotransmitters other than DA or GABA are likely to be present in the VTA. Given the pronounced phenotypic diversity of neurons in this region, we have proposed that additional cell types, such as those that express the neurotransmitter glutamate may also be present in this area. Thus, by using in situ hybridization histochemistry we investigated whether transcripts encoded by genes for the two vesicular glutamate transporters, VGluT1 or VGluT2, were expressed in the VTA. We found that VGluT2 mRNA but not VGluT1 mRNA is expressed in the VTA. Neurons expressing VGluT2 mRNA were differentially distributed throughout the rostro-caudal and medio-lateral aspects of the VTA, with the highest concentration detected in rostro-medial areas. Phenotypic characterization with double in situ hybridization of these neurons indicated that they rarely co–expressed mRNAs for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, marker for DAergic neurons) or glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD, marker for GABAergic neurons). Based on the results described here, we concluded that the VTA contains glutamatergic neurons that in their vast majority are clearly non-DAergic and non-GABAergic.

Keywords: dopamine, midbrain, reward, Sprague–Dawley rat, substantia nigra, VGluT2

Introduction

The ventral tegmental area (VTA) is thought to play a role in goal-directed behaviour and in the reward processing of natural rewards and of several drugs of abuse (Schultz, 2002; Wise, 2004). Two populations of VTA neurons, dopaminergic (DAergic) neurons and GABAergic neurons, have been extensively characterized, but evidence is accumulating that other subpopulations may also exist in this area containing a pronounced diversity of neurons (Phillipson, 1979b). Based on electrophysiological and pharmacological properties, VTA neurons have been classified as primary, secondary and tertiary (Grace & Onn, 1989; Johnson & North, 1992; Cameron et al., 1997; Ungless et al., 2004). Primary neurons are DAergic (Cameron et al., 1997), and target cortical and limbic structures. Both primary and tertiary neurons exhibit a hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) and long duration action potentials. Secondary neurons are GABAergic, lack Ih, and have shorter duration potentials. Neurons previously classified as tertiary are hyperpolarized by serotonin and enkephalin but are apparently not homogeneous as to their neurotransmitter; only one-third of these cells are DAergic in the guinea pig VTA (Cameron et al., 1997). Moreover, recent studies have shown that VTA neurons lacking dopamine and Ih could be excited by aversive stimuli in anaesthetized rats (Ungless et al., 2004). These observations indicate that neurons that use neurotransmitters other than DA and GABA are likely to be present in VTA.

We investigated whether glutamatergic neurons are present in the rat VTA. Glutamate, a major excitatory neurotransmitter in the mammalian central nervous system (CNS), is transported into synaptic vesicles at presynaptic terminals by a distinct family of proteins known as vesicular glutamate transporters (VGluTs). Three isoforms of the vesicular glutamate transporter, VGluT1, VGluT2 and VGluT3, are present in the CNS. VGluT1 and VGluT2 are expressed in glutamatergic neurons (Bellocchio et al., 1998, 2000; Takamori et al., 2000, 2001; Bai et al., 2001;Fremeau et al., 2001; Fujiyama et al., 2001; Hayashi et al., 2001; Herzog et al., 2001; Varoqui et al., 2002). On the other hand, VGluT3 is found in GABAergic neurons as well as in cholinergic interneurons, monoamine neurons and glia (Gras et al., 2002; Fremeau et al., 2002; Schafer et al., 2002). As VGluT1 and VGluT2 are glutamate transporters restricted to known glutamatergic neurons, their presence has become a reliable molecular phenotypic marker to identify glutamatergic neurons. VGluT1 and VGluT2 are highly concentrated in synaptic vesicles in axonal terminals of glutamatergic neurons (Fremeau et al., 2001; Fujiyama et al., 2001; Herzog et al., 2001). However, these proteins haven’t been detected in other neuronal compartments, such as cell bodies, dendrites, and axons. Thus, cellular detection of transcripts encoding VGluT1 or VGluT2 is so far the only available and reliable method to label cell bodies of glutamatergic neurons. In the present study we investigated whether glutamatergic neurons are present in the VTA by detecting cellular expression of VGluT1 or VGluT2 mRNAs in this brain structure.

Materials and methods

Tissue preparation

Adult Sprague–Dawley male rats (300–350 g body weight) were anaesthetized with chloral hydrate (35 mg/100 g) and perfused transcardially with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.3. Brains were left in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 h at 4 °C, rinsed with PB and transferred sequentially to 12%, 14% and 18% sucrose solutions in PB. Coronal serial sections of 20-µm thickness were prepared. All animal procedures were approved by the NIDA Animal Care and Use Committee.

Single in situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as described previously (Morales & Bloom, 1997). Cryosections were incubated for 10 min in PB containing 0.5% Triton X-100, rinsed 2 × 5 min with PB, treated with 0.2 m HCl for 10 min, rinsed 2 × 5 min with PB and then acetylated in 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1 m triethanolamine, pH 8.0 for 10 min. Sections were rinsed 2 × 5 min with PB, postfixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, and after a final rinse with PB, were hybridized for 16 h at 55 °C in hybridization buffer (50% formamide; 10% dextran sulphate; 5 × Denhardt’s solution; 0.62 m NaCl; 50 mm DTT; 10 mm EDTA; 20 mm PIPES, pH 6.8; 0.2% SDS; 250 µg/mL salmon sperm DNA; 250 µg/mL tRNA) containing [35S]- and [33P]-labelled single-stranded antisense or sense of rat VGluT1 (nucleotides 1391–1976, Accession # NM-053859.1) or VGluT2 (nucleotides 1704–2437, Accession # NM-053427) probes at 107 cpm/mL. Plasmids that contained the VGluT1 and VGluT2 were generously provided by Dr Robert H. Edwards (University of California, San Francisco). Sections were treated with 4 µg/mL RNaseA at 37 °C for 1 h, washed with 1 × SSC, 50% formamide at 55 °C for 1 h, and with 0.1 × SSC at 68 °C for 1 h. After the last SSC wash, sections were rinsed with TBS buffer (20 mm Tris HCl, 0.5 m NaCl, pH 8.2). Sections were mounted on coated slides, air dried, dipped in nuclear track emulsion and exposed for several weeks prior to development.

Double in situ hybridization

For double hybridization, cryosections were processed as indicated for single hybridization but hybridization was performed with buffer containing [35S]- and [33P]-labelled single-stranded antisense rat VGluT2 (nucleotides 1704–2437, Accession # NM-053427) probes at 107 cpm/mL together with the single-stranded rat digoxigenin-labelled antisense probe for TH (nucleotides 14–1165, Accession # NM012740) or the digoxigenin-labelled antisense probes for the two isoforms of rat glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD65 and GAD67). Plasmids that contained GAD65 and GAD67 were generously provided by Dr Allan Tobin (University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA). Sections were treated with 4 µg/mL RNaseA at 37 °C for 1 h, washed with 1 × SSC, 50% formamide at 55 °C for 1 h, and with 0.1 × SSC at 68 °C for 1 h. After the last SSC wash, sections were rinsed with TBS buffer (20 mm Tris HCl, 0.5 m NaCl, pH 8.2). Afterwards, sections were incubated with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibody against digoxigenin (Roache Applied Science; Indianapolis, IN) overnight at 4 °C; alkaline phosphatase reaction was developed with nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (Life Technologies; Gaithersburg, MD) yielding a purple reaction product. Sections were mounted on coated slides, air dried, and photographed under bright field microscopy. Lastly, slides were dipped in nuclear track emulsion and left for several weeks prior to development.

Combination of in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry

After radioactive single in situ hybridization, sections were rinsed with PB and incubated for 1 h in PB supplemented with 4% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.3% Triton X-100. Sections were then incubated with anti-TH mouse monoclonal antibody (1 : 500, Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) overnight at 4 °C. After rinsing 3 × 10 min in PB, sections were processed with an ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The material was incubated for 1 h at room temperature (RT) in a 1 : 200 dilution of the biotinylated secondary antibody, rinsed with PB, and incubated with avidinbiotinylated horseradish peroxidase for 1 h. Sections were rinsed and the peroxidase reaction was then developed with 0.05% 3,3-diaminobenzidine-4 HCl (DAB) and 0.003% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Sections were mounted on coated slides, air dried, dipped in nuclear track emulsion and exposed for several weeks prior to development.

Data analysis

Sections were viewed, analysed and photographed with bright field or epiluminescence microscopy using a Nikon Eclipse E 800 microscope fitted with a 4× and 20× objective lens. VTA subdivisions were traced according to Paxinos & Watson (2005). Single and double-labelled neurons were observed within each traced region at high power (20× objective lens) and marked electronically. The cells expressing VGluT2, TH, GAD, VGluT2/TH and VGluT2/GAD transcripts were counted separately. A neuron was considered to express TH mRNA or GAD mRNA when its soma was clearly labelled as purple. A TH- or GAD-expressing neuron was included in the calculation of total population of TH- or GAD-expressing cells when the stained cell was at least 5 µm in diameter and the silver grains were observed in the same focal plane. A neuron was considered double labelled when its soma was purple and contained an aggregation of silver particles over the purple cell but in the same focal field. Three observers counted labelled cells. The background was evaluated from slides hybridized with sense probes. Images were opened and processed with an Adobe Photoshop 7 program (Adobe Systems Incorporated, Seattle, WA).

Results

Neurons expressing VGluT2 mRNA are present in the VTA and in some of its surrounding areas

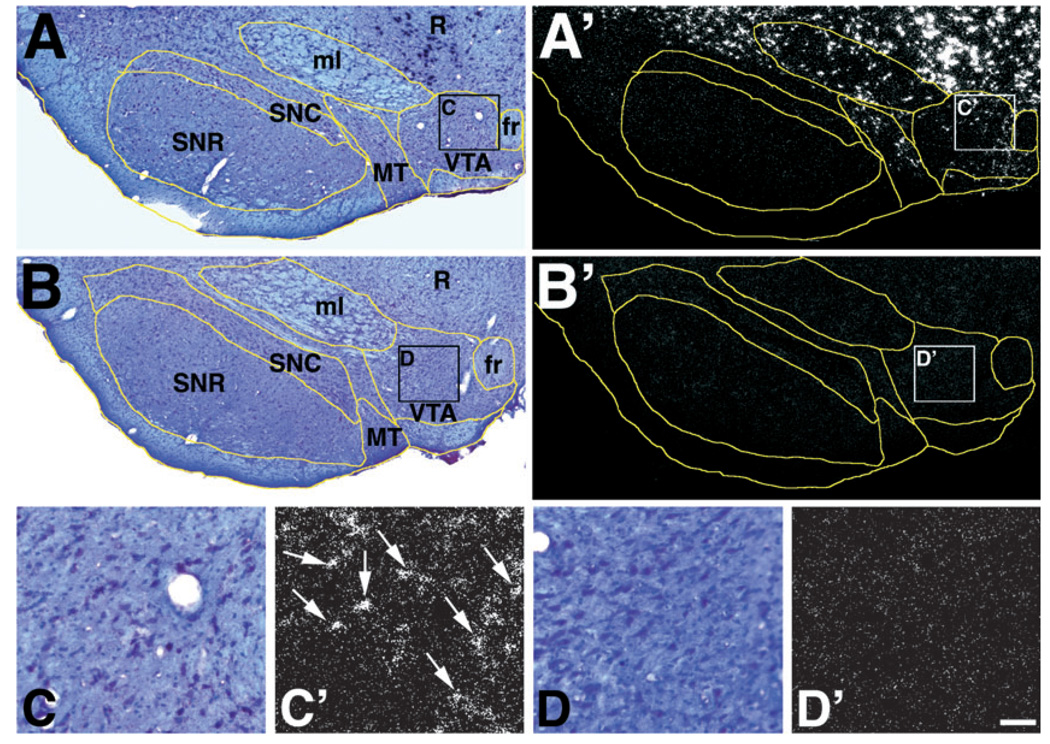

By using VGluT2 radioactive antisense riboprobes, we detected expression of VGluT2 mRNA in the VTA as well as in several of its surrounding areas (Fig. 1A′ and C′). Signal for VGluT2 mRNA was not detected when brain sections were hybridized with the corresponding VGluT2 sense riboprobe (Fig. 1B′ and D′). Within the VTA, neurons expressing VGluT2 mRNA were differentially distributed throughout its various subregions (Figs 2A′, B′ and C′, and 3A′ and C′). Several areas in the vicinity of the VTA consistently showed high levels of VGluT2 mRNA expression. These areas included the medial terminal nucleus of the accessory optic tract (Fig. 1A′), areas adjacent to the medial portion of the VTA (interfascicular nucleus and caudal linear nucleus, Fig. 3A′), areas medio-ventral to the VTA (supramammilary nucleus and interpeduncular nucleus, Fig. 3A′) and the red nucleus (Figs 1A′ and 3′). In contrast, we hardly ever observed expression of VGluT2 mRNA in the substantia nigra compacta (SNC) or substantia nigra reticulata (SNR; Figs 1A′, 2A′ and B′, and 3A′). While we found high levels of VGluT1 mRNA expression in cortical and limbic structures, VGluT1 was not detected in the VTA.

FIG. 1.

Expression of VGluT2 mRNA in the VTA. (A and A′) Frames A (bright field microscopy) and A′ (epiluminescence microscopy) of a section hybridized with the antisense radioactive VGluT2 riboprobe. At low magnification in frame A′ notice positive signal for the detection of VGluT2 mRNA in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), medial terminal nucleus of the accessory optic tract (MT), medial lemniscus (ml) and red nucleus (R). Signal for VGluT2 mRNA is not seen in the substatia nigra compacta (SNC), substantia nigra reticulata (SNR) or fasciculus retroflexus (fr). (B and B′) Frames B (bright field microscopy) and B′ (epiluminescence microscopy) of a section hybridized with sense radioactive VGluT2 riboprobe showing lack of signal. (C and D′) Frames C, C′, D and D′ are high magnification micrographs of the VTA shown at low magnification in A, A′, B and B′. Arrows in C′ indicate cells expressing mRNA within the VTA. Bregma −5.16 mm. Scale bar shown in D′ represents 230 µm for A, A′, B and B′; 42 µm for C, C′, D and D′.

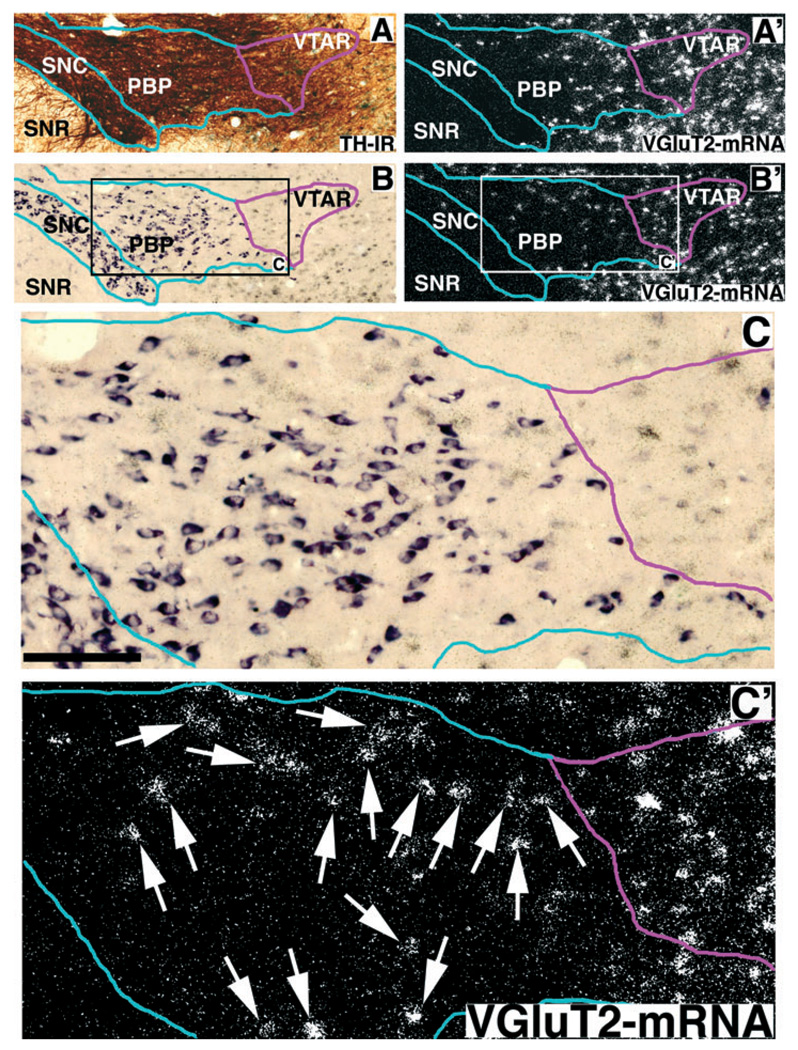

FIG. 2.

Expression of VGluT2 mRNA (white grains in A′, B′, and C′), TH immunoreactivity (dark brown label in A) and TH mRNA (purple label in B and C) in the rostral VTA. Frames A and B are adjacent sections at low power in bright field. The blue outline delimits the VTA (parabrachial pigmental area, PBP) and substantia nigra compacta (SNC) dopamine groups as defined by the extent of their cell bodies (purple cells in B and C). The magenta outline delimits the ventral tegmental area rostral (VTAR), which is rich in TH immunoreactive dendrites (dark brown label in A) but contains very few neurons expressing TH mRNA (B and C). Neurons expressing VGluT2 mRNA in the PBP and VTAR appear as aggregates of white grains in frames A′, B′ and C′. Note the high concentration of neurons expressing VGluT2 mRNA in the VTAR, an area having only occasional neurons expressing TH mRNA (compare B with B′), but with high levels of TH immunoreactive dendrites (compare A with B). Arrows in C′ indicate VGluT2 mRNA expressing neurons in the PBP. Frames C (bright field microscopy) and C′ (epiluminescence microscopy) are enlargement of the area delimited by rectangles in B and B′. Bregma −4.80 mm. Scale bar shown in C represents 480 µm for A, A′, B and B′ and 125 µm for C and C′.

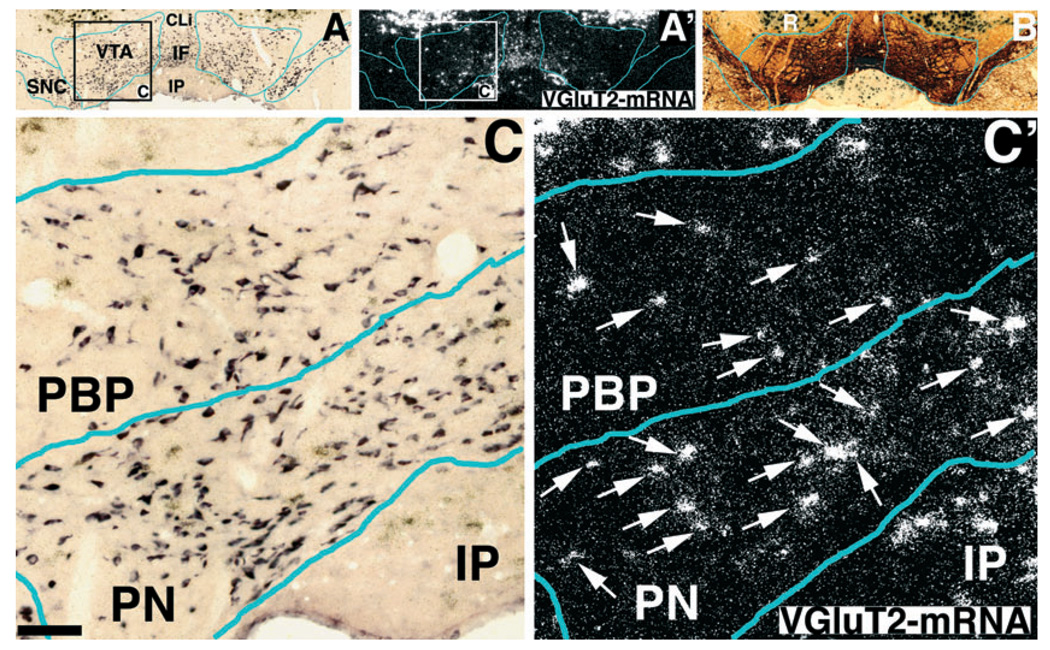

FIG. 3.

Expression of VGluT2 mRNA (white grains in A′ and C′), TH mRNA (purple label in A and C) and TH immunoreactivity (dark brown label in B) in the medial VTA. Frames A and B are adjacent sections at low power in bright field. In frame A′ the cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA are seen in the VTA, red nucleus (R), caudal linear nucleus of the raphe (CLi), interfascicular nucleus (IF) and interpeduncular nucleus (IP). Note high levels of VGluT2 mRNA expression in red nucleus clearly seen as black dots under bright field (A and B) and white grains under epiluminescence microscopy (A′). Squares in A and A′ delimitate low magnification areas shown at higher magnifications in C and C′. (C′) Note higher concentration of cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA (arrows) in the paranigral nucleus (PN) than in the parabrachial pigmented nucleus (PBP). Bregma −5.40 mm. Scale bar shown in C represents 800 µm for A, A′ and B, and 80 µm for C and C′.

Neurons expressing VGluT2 mRNA have different patterns of distribution in the VTA subregions

To define the boundaries of the VTA and to determine the distribution of cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA in relation to TH containing cells, we prepared two sets of serial coronal brain sections and processed them with two types of double-labelling techniques. The first set of sections was used to simultaneously label by double in situ hybridization neurons expressing either VGluT2 mRNA or TH mRNA (Figs 2 and 3). The second set of sections was processed by in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry to label cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA (detected by in situ hybridization) and cell bodies and dendrites containing TH protein (detected by immunohistochemistry; Figs 2 and 3). The subregional distribution of the cells expressing VGluT2 and TH was analysed at the rostral, medial and caudal levels of the VTA.

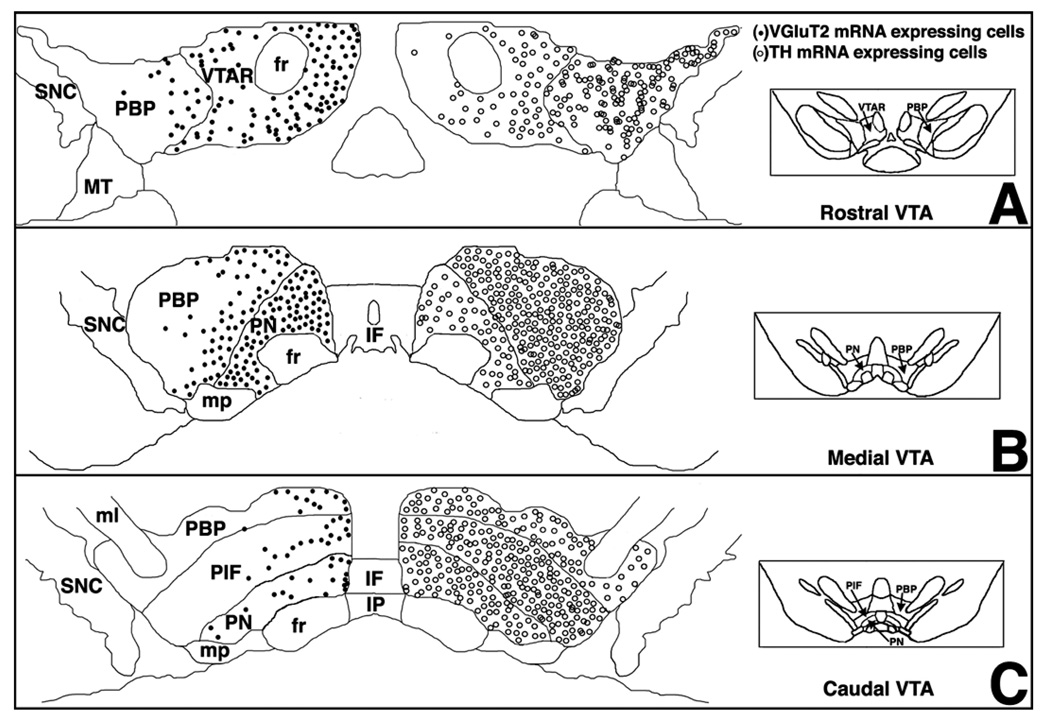

Distribution of VGluT2 and TH neurons at the rostral level of the VTA

We observed cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA in the parabrachial pigmental area (PBP, a subregion in the rostro-lateral portion of the VTA) and in the ventral tegmental area rostral (VTAR, a subregion in the rostro-medial region of the VTA) (Figs 2A′, B′ and C′, and 4A). The highest density of VGluT2 cells was found in the VTAR (338 cells/mm2, Table 1), in comparison, we detected approximately five times fewer of these cells in the PBP (62 cells/mm2, Table 1). Out of the total population of cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA at the rostral level of the VTA, the majority were found in the VTAR (85%, Table 2), and only 15% (Table 2) in the PBP.

FIG. 4.

(A–C) Summary diagram of rostro-caudal distribution of cells expressing VGluT2 (closed circles) or TH (open circles) mRNAs in the VTA. Note that cells expressing TH mRNA are most densely aggregated in the caudal VTA, where cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA are sparse. Also, in the rostral and medial VTATH neurons are more densely aggregated in the PBP than in the PN or VTAR, where the converse is true for VGluT2 cells. Cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA or TH mRNA in neighbouring areas of the VTA are not included in the diagram. MT, medial terminal nucleus of the accessory optic tract; ml, medial lemniscus. Subregions of the VTA are named according to Paxinos & Watson (2005). Bregma −5.04 mm for A, −5.28 mm for B and −5.52 mm for C.

TABLE 1.

Density of neurons expressing VGluT2 or TH mRNAs in the rostro-caudal sub-regions of the VTA

| Density of neurons (per mm2) expressing VGluT2 mRNA cells* |

Density of neurons (per mm2) expressing TH mRNA cells† |

|

|---|---|---|

| Rostral VTA‡ | ||

| Ventral tegmental area rostral | 338 ± 26 | 280 ± 81 |

| Parabrachial pigmental area | 62 ± 8 | 702 ± 45 |

| Medial VTA§ | ||

| Parabrachial pigmental area | 112 ± 5 | 432 ± 46 |

| Paranigral nucleus | 282 ± 34 | 183 ± 31 |

| Caudal VTA¶ | ||

| Parabrachial pigmental area | 38 ± 9 | 349 ± 25 |

| Parainterfasicular nucleus | 75 ± 16 | 651 ± 51 |

| Paranigral nucleus | 140 ± 19 | 724 ± 172 |

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Quantitative analysis at three levels of the VTA (rostral, medial and caudal) was conducted to determine the rostro-caudal density of neurons expressing VGluT2 mRNA or TH mRNA within the different subregions of the VTA (ventral tegmental area rostral, parabrachial pigmental area, parainterfasicular nucleus and paranigral nucleus). Density of cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA and density of cells expressing TH mRNA were calculated at the

rostral (ten sections, six rats),

medial (nine sections, five rats) and

caudal (four sections, three rats) levels of the VTA. Rostral VTA, −4.68 mm to −5.15 mm from Bregma; medial VTA, −5.16 mm to −5.51 mm from Bregma; caudal, −5.52 mm to −5.75 mm from Bregma.

Number of neurons expressing VGluT2 mRNA per area (density) within each VTA subregion.

Number of neurons expressing TH mRNA per area (density) within each VTA subregion.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of neurons expressing VGluT2 or TH mRNAs in the rostro-caudal sub-regions of the VTA

| Neurons expressing VGluT2 mRNA* |

(n) | Neurons expressing TH mRNA† |

(n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rostral VTA‡ | 100 | (1204) | 100 | (2314) |

| Ventral tegmental area rostral | 84.8 ± 0.7 | (1032) | 26.9 ± 1.1 | (584) |

| Parabrachial pigmental area | 15.2 ± 0.7 | (172) | 73.1 ± 1.1 | (1730) |

| Medial VTA§ | 100 | (1278) | 100 | (2498) |

| Parabrachial pigmental area | 44.5 ± 1.5 | (531) | 82.9 ± 1.3 | (2070) |

| Paranigral nucleus | 55.5 ± 1.5 | (747) | 17.1 ± 1.3 | (428) |

| Caudal VTA¶ | 100 | (216) | 100 | (141) |

| Parabrachial pigmental area | 24.6 ± 3.1 | (54) | 38.8 ± 2.1 | (522) |

| Parainterfasicular nucleus | 40.9 ± 2.6 | (88) | 41.7 ± 1.0 | (599) |

| Paranigral nucleus | 35.5 ± 1.4 | (74) | 19.4 ± 1.8 | (294) |

Data are presented as mean percentages ±SEM. Quantitative analysis at three levels of the VTA (rostral, medial and caudal) was conducted to determine the rostro-caudal distribution of neurons expressing VGluT2 mRNA or TH mRNA within the different subregions of the VTA (ventral tegmental area rostral, parabrachial pigmental area, parainterfasicular nucleus and paranigral nucleus). Density of cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA and density of cells expressing TH mRNA were calculated at the

rostral (ten sections, six rats),

medial (nine sections, five rats) and

caudal (four sections, three rats) levels of the VTA. Rostral VTA = −4.68 mm to −5.15 mm from Bregma; medial VTA, −5.16 mm to −5.51 mm from Bregma; caudal, −5.52 mm to −5.75 mm from Bregma.

At each VTA level, the percentage of neurons expressing VGluT2 mRNA within each VTA subregion was calculated from the total population of cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA.

At each VTA level, the percentage of neurons expressing TH mRNA within each VTA subregion was calculated from the total population of cells expressing TH mRNA.

The density of neurons expressing TH mRNA varied across the rostral level of the VTA; the highest density of these neurons was observed in the PBP with an average density of 702 cells/mm2 (Table 1; Fig. 2B and C). This subregion contains 73% of all cells expressing TH mRNA at the rostral level of the VTA (Table 2). On the other hand, in the VTAR the average density of neurons containing TH mRNA was 280 cells/mm2 (Table 1), and contains only 27% of all cells expressing TH mRNA at the rostral VTA (Table 2). In contrast to the distribution of TH mRNA, TH immunoreactivity was strong in the VTAR (Fig. 2A), thus indicating that much of the TH immunolabel signal seen in this subregion is from dendrites.

We concluded that at the rostral level of the VTA, the amount of neurons containing either VGluT2 mRNA or TH mRNA was similar in the VTAR. In contrast, in the PBP we found ten times more cells expressing TH mRNA than VGluT2 mRNA.

Distribution of VGluT2 and TH neurons at the medial level of the VTA

Cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA were also differentially distributed across the medial VTA (Fig. 3A′ and C′). The density of VGluT2 containing cells was 112 cells/mm2 in the PBP (Table 1), a higher density was found in the paranigral nucleus, (PN, 282 cells/mm2, Table 1). Within the PN, the VGluT2 cells were more concentrated towards the medial VTA; fewer cells were found in the lateral portion (Fig. 2C). Rather than the cellular distribution found at the rostral level of the VTA (85% of the VGluT2 cells were in the VTAR and 15% in the PBP), the VGluT2 cells were more evenly distributed (44% in the PBP and 55% in the PN) in the two subregions of the medial VTA.

Density of neurons expressing TH mRNA also differed across the PBP and PN (Figs 3A and C, and 4B). The density of cells expressing TH mRNA was approximately twice as high in the PBP (432 cells/mm2, Table 1) than in the in the PN (183 cells/mm2, Table 1). The PBP contained an average of 83% of the total population of neurons expressing TH mRNA in the medial VTA (Table 2); whereas 17% were located in the PN (Table 2).

We concluded that at the medial level of the VTA, the quantity of neurons containing VGluT2 mRNA in the PN was 1.5 times higher than that of neurons expressing TH mRNA. In contrast, in the PBP we found four times more cells expressing TH mRNA than VGluT2 mRNA.

Distribution of VGluT2 and TH neurons at the caudal level of the VTA

Cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA were identified in the three subregions of the caudal VTA, the PBP, the parainterfasicular nucleus (PIF) and the PN. VGluT2 cells were twice as concentrated in the PIF (75 cells/mm2, Table 1) than in the PBP (38 cells/mm2, Table 1). The highest density of VGluT2 cells was detected in the PN (140 cells/mm2, Table 1). Out of the total population of cells expressing VGluT2 in the caudal VTA, 41% was detected in the PIF and 35% in the PN, and the lowest percentage was found in the PBP (24%, Table 2).

Cells expressing TH mRNA were less concentrated in the PBP (349 cells/mm2, Table 1) than in the PIF (651 cells/mm2, Table 1), and the PN (724 cells/mm2, Table 1). Out of the total population of cells expressing TH mRNA in the caudal VTA, 39% were found in the PBP and 42% in the PIF and fewer in the PN (19%, Table 2). Thus, the caudal PN is the VTA subregion with the highest number of TH cells per area but contains only 19% of the total population of TH neurons of the caudal VTA.

We concluded that neurons expressing the VGluT2 mRNA in the caudal VTA, similar to those at the medial level of the VTA, were mainly concentrated in the PN. Each of the subregions of the caudal VTA has 5–10 times more cells expressing TH mRNA than VGluT2 mRNA.

Neurons expressing VGluT2 mRNA constitute a third phenotype of neurons in the VTA

As DAergic and GABAergic cells are the established neuronal populations in the VTA, we used double in situ hybridization to determine if neurons expressing VGluT2 mRNA belong to any of these VTA cellular populations. We prepared serial coronal brain sections and used one set of sections to process with double in situ hybridization histochemistry for the simultaneous detection of TH mRNA with a digoxigenin sense riboprobe (Figs 5A, B and C, and 6A′ and B′) and VGluT2 mRNA with a radioactive sense riboprobe (Figs 5A′ and B′, and 6A and B). We processed the other set of serial sections with double in situ hybridization histochemistry to simultaneously detect GAD mRNA with a digoxigenin sense riboprobe (Figs 7A, B and C, and 8A′ and B′) and VGluT2 mRNA with a radioactive sense riboprobe (Figs 7A′ and B′, and 8A and B). We evaluated coexpression of TH mRNA and VGluT2 mRNA at the cellular level (Fig. 6B and B′) and determined that coexpression of both transcripts was very rare; we found only seven cells coexpressing VGluT2 and TH mRNAs out of 2583 cells that expressed VGluT2 mRNA and out of 6357 cells that expressed TH mRNA. Similarly, our analysis of coexpression of VGluT2 mRNA and GAD mRNA at the cellular level (Fig. 8B and B′) indicated that coexpression of both transcripts was rare. For example, we found only 22 cells coexpressing VGluT2 and GAD mRNAs out of 1014 cells that expressed VGluT2 mRNA and of 547 cells that expressed GAD mRNA. Thus, neurons that express VGluT2 mRNA comprise a third and relatively distinct cellular population in the VTA.

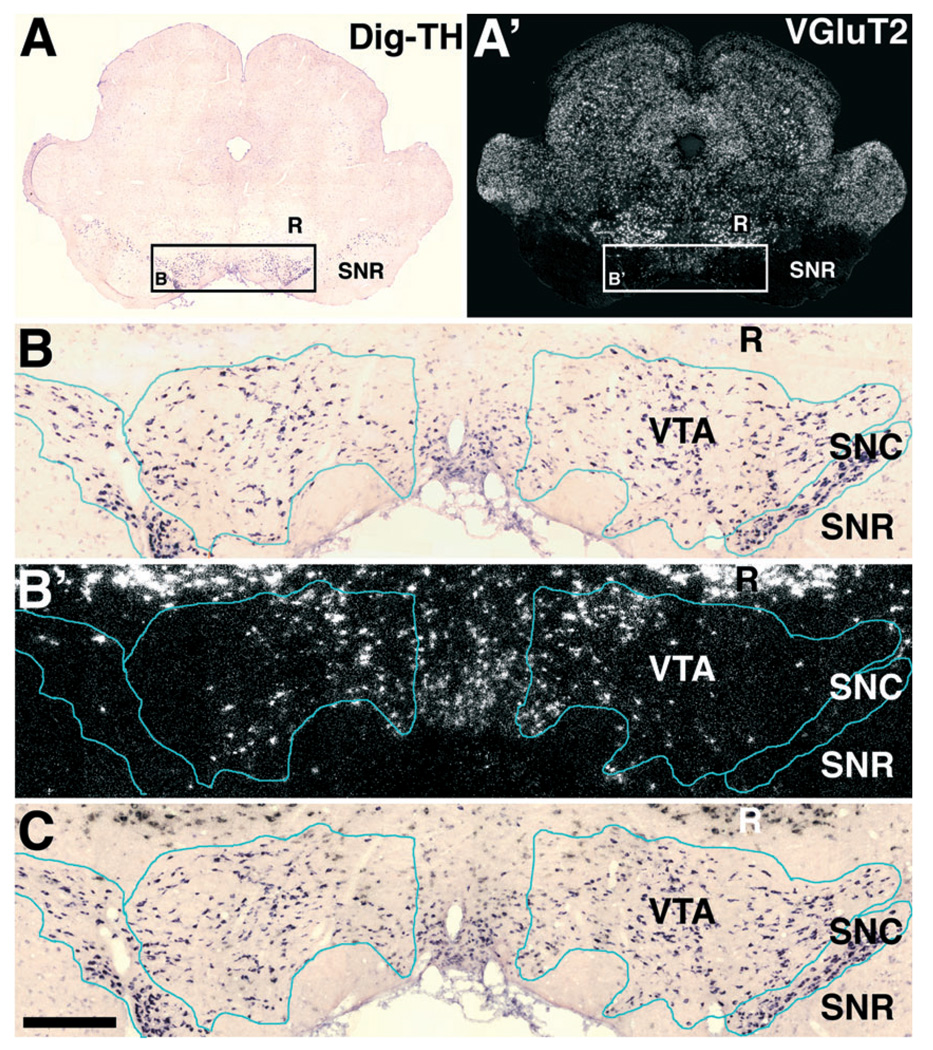

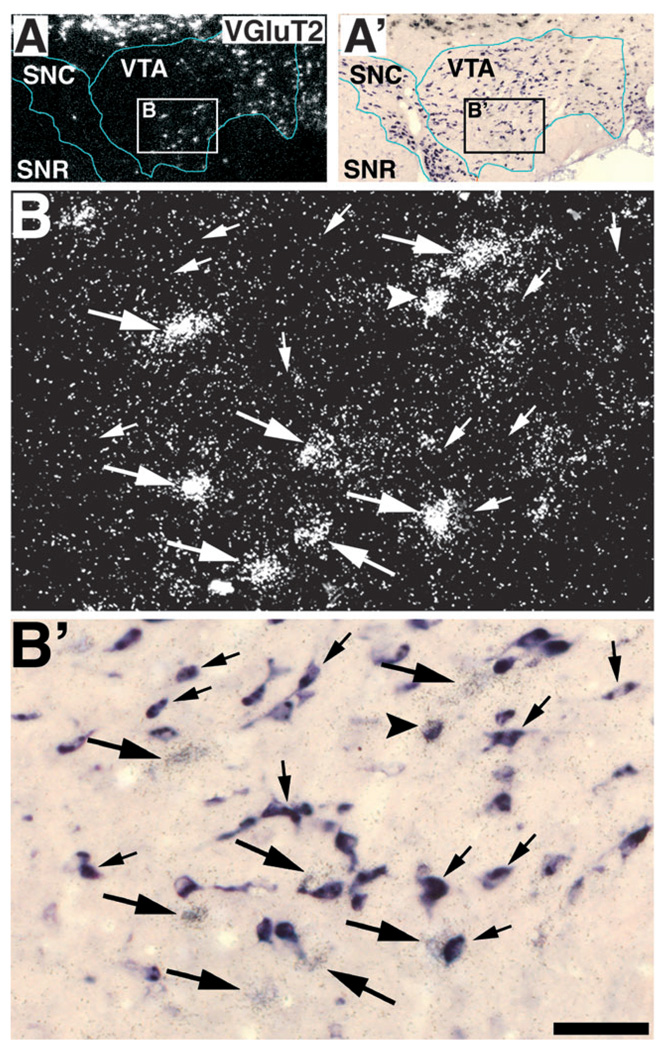

FIG. 5.

Expression of VGluT2 mRNA in the VTA. (A and A′) Low magnification of a section simultaneously hybridized with Dig-TH (A) and radioactive VGluT2 (A′) antisense riboprobes. Rectangle in A delimitates low magnification area shown at higher magnification in C and C. Rectangle in A′ delimitates low magnification area shown at higher magnification in B′. (B) Bright field microscopy of TH expressing cells seen before developing silver grains. (B′) Epiluminescence microscopy of the same section showing cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA. (C) Bright field microscopy of the same section after developing silver grains, note cells expressing either TH mRNA (purple cells) or VGluT2 mRNA (black grains). Bregma −5.40 mm. Scale bar shown in C represents 3.8 mm for A and A′ and 700 µm for B, B′ and C.

FIG. 6.

VGluT2 mRNA is mainly expressed in cells lacking expression of TH mRNA. (A and A′) Low magnification of a section simultaneously hybridized with Dig-TH (A) and radioactive VGluT2 (A′) antisense riboprobes. Rectangle in A delimitates low magnification area shown at higher magnification in B and B′. (B and B′) Pair of micrographs showing TH mRNA expressing cells in purple lacking VGluT2 mRNA (small arrows), and cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA lacking TH mRNA (large arrows). One cell appears to coexpress VGluT2 and TH transcripts (arrow-head). Bregma −5.40 mm. Scale bar shown in B′ represents 1 mm for A and A′, and 130 µm for B and B′.

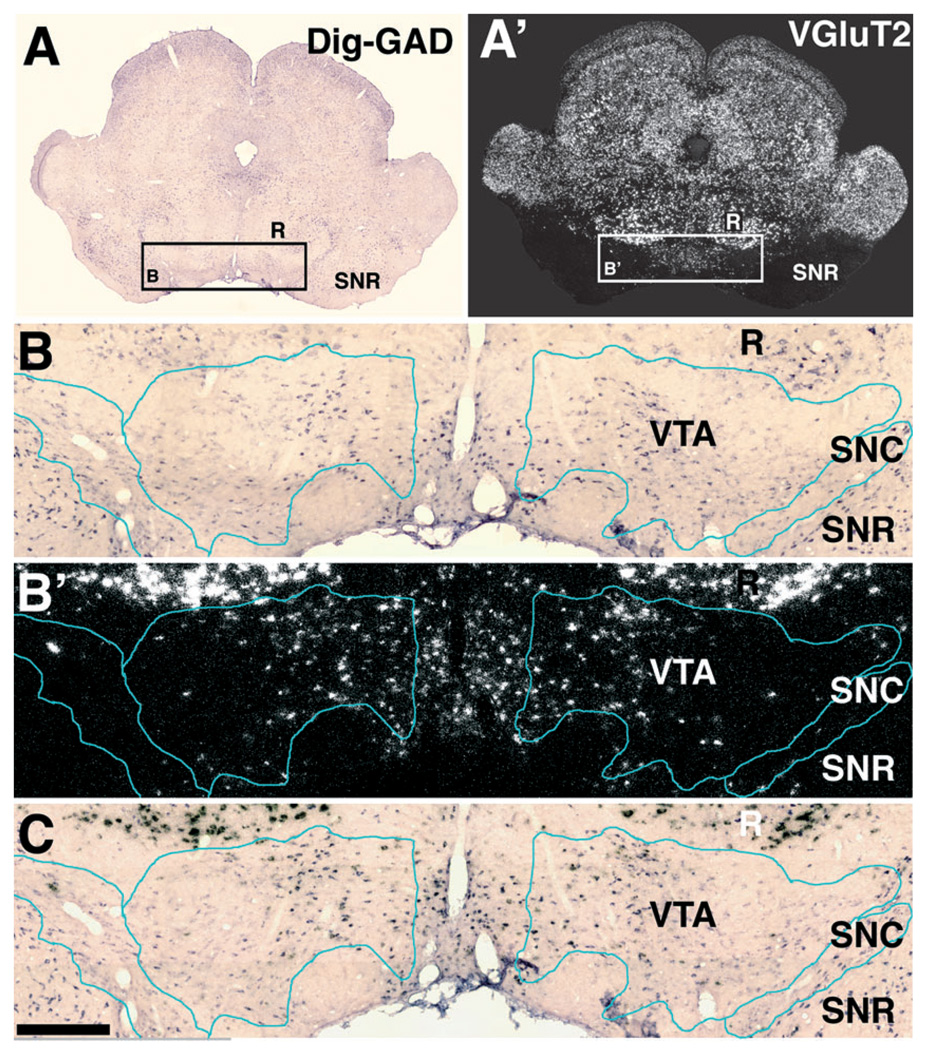

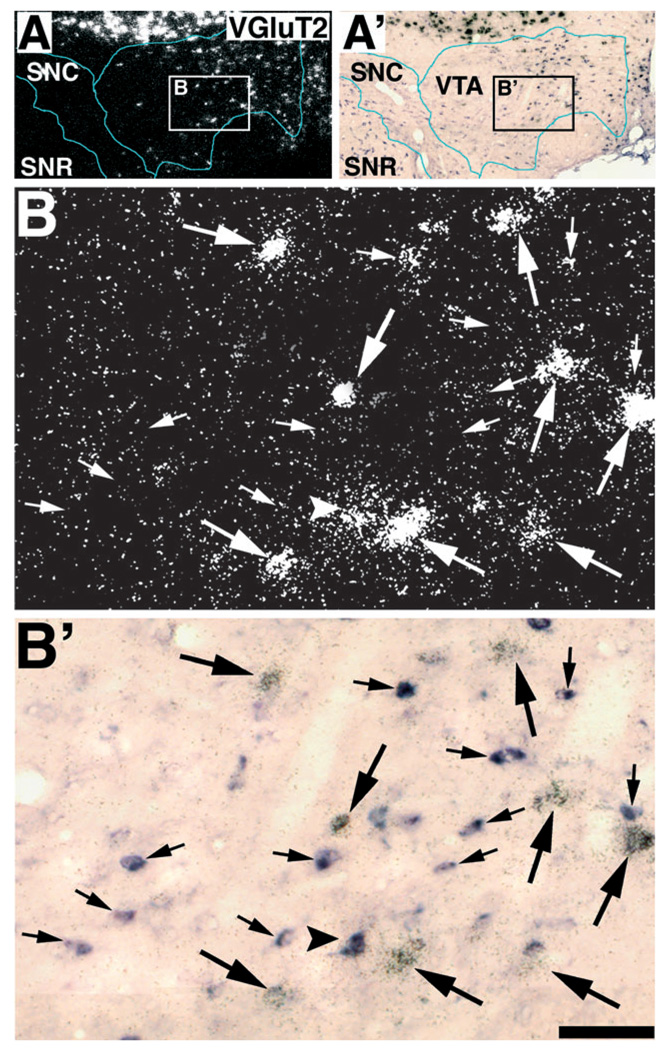

FIG. 7.

Expression of VGluT2 mRNA in the VTA. (A and A′) Low magnification of a section simultaneously hybridized with Dig-GAD (A) and radioactive VGluT2 (A′) antisense riboprobes. Rectangle in A delimitates low magnification area shown at higher magnification in C and C. Rectangle in A′ delimitates low magnification area shown at higher magnification in B′. (B) Bright field microscopy of GAD expressing cells seen before developing silver grains. (B′) Epiluminescence microscopy of the same section showing cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA. (C) Bright field microscopy of the same section after developing silver grains, note cells expressing either GAD mRNA (purple cells) or VGluT2 mRNA (black grains). Bregma −5.40 mm. Scale bar shown in C represents 3.8 mm for A and A′ and 700 µm for B, B′ and C.

FIG. 8.

VGluT2 mRNA is mainly expressed in cells lacking expression of GAD mRNA. (A and A′) Low magnification of a section simultaneously hybridized with Dig-GAD (A) and radioactive VGluT2 (A′) antisense riboprobes. Rectangle in A delimitates low magnification area shown at higher magnification in B and B′. (B and B′) Pair of micrographs showing GAD mRNA expressing cells in purple lacking VGluT2 mRNA (small arrows), and cells expressing VGluT2 mRNA lacking GAD mRNA (large arrows). One cell appears to coexpress VGluT2 and GAD transcripts (arrow-head). Bregma −5.40 mm. Scale bar shown in B′ represents 1 mm for A and A′, and 130 µm for B and B′.

Discussion

Cellular detection of VGluT2 mRNA in the VTA and adjacent regions

We detected cellular expression of VGluT2 mRNA, but not of VGluT1, in many cells in the VTA. While we hardly ever observed expression of VGluT2 mRNA in the substantia nigra compacta or substantia nigra reticulata, we consistently found high levels of VGluT2 mRNA expression in other brain areas adjacent to the VTA, such as supramammilary nucleus, the medial terminal nucleus of the accessory optic tract, interfascicular nucleus, caudal linear nucleus, and the red nucleus. We were not able to detect radioactive signal for VGluT2 mRNA in the VTA using photographic film or phosphor plates. The false negative expression of VGluT2 mRNA in the VTA was due to the high levels of VGluT2 mRNA present in many cells of the thalamus, and some of the surroundings areas of the VTA, that saturates the signal and consequently masks detection of the radioactive signal in the VTA. To overcome this problem, we analysed brain sections that were hybridized with radioactive riboprobes and then exposed for a month to photographic emulsion. By applying this approach, we were able to detect cellular expression of VGluT2 mRNA in the different subregions of the VTA.

Neurons expressing VGluT2 mRNA have different patterns of distribution in the VTA subregions. Glutamatergic neurons are not homogeneously distributed in the VTA. The highest density of glutamatergic neurons was found in the rostral VTA in the subregion known as the ventral tegmental region rostral (VTAR), and at the medial level of the VTA in the paranigral nucleus (PN). From the rostral to the caudal aspects of the VTA, the lowest density of glutamatergic neurons was found in the parabriachial pigmental area (PBP). In general, whereas glutamatergic neurons were often seen in the rostral and medial VTA, the caudal VTA contains very few glutamatergic neurons (Fig. 4). Several studies have established functional differences between rostral and ventral aspects of the VTA (Ikemoto et al., 1998; Zangen et al., 2002; Olson et al., 2005; Rodd et al., 2005). Factors such as neuronal connectivity and selective distribution of cells with specific phenotype may contribute to functional differences between the rostral (anterior) and caudal (posterior) VTA. Thus, glutamatergic neurons with a rostral-caudal gradient distribution in the VTA may play a role in the rostro-caudal functional differences in the VTA by exercising an excitatory control on local DAergic or GABAergic neurons targeting different brain areas.

Glutamatergic and DAergic neurons in the subregions of the VTA

DAergic neurons are the best characterized and most abundant cell type in the VTA. Their distribution is frequently used (Phillipson, 1979a) to define the boundaries of this brain region. Thus, we compared here the cellular distribution of VTA glutamatergic neurons and DAergic neurons in the different subregions at rostro-caudal levels of the VTA. We calculated that at the rostral level of the VTA within the VTAR the density of glutamatergic neurons is slightly higher than that of DAergic neurons, but the PN at the medial level contains approximately three glutamatergic neurons for every two DAergic, the PBP is the subregion with the lowest density of glutamatergic neurons throughout the entire VTA. Based on the subregional distribution of glutamatergic neurons alone, it is not possible to infer the participation of these neurons in specific brain functions. Nevertheless, it has been suggested that DAergic cells of the paranigral nucleus project to the nucleus accumbens (Phillipson, 1979a) and are associated with reward and locomotor activity (Le Moal&Simon, 1991; Schultz, 1998; Spanagel& Weiss, 1999), whereas DAergic cells of the parabrachial nucleus project to the cortical structures, and are involved in the modulation of cognitive functions (Le Moal & Simon, 1991; Williams & Goldman-Rakic, 1998). Although we found the highest density of glutamatergic neurons in the paranigral nucleus, it remains to be established if VTA glutamatergic neurons interact with DAergic neurons that project to the nucleus accumbens or cortical structures. Alternatively, VTA glutamatergic neurons may target the same terminal fields as DAergic neurons, and thus affect excitatory neurotransmission in these brain structures.

Glutamatergic cells constitute a third phenotype of neurons in the VTA

We found minimal expression of VGluT2 mRNA in DAergic or GABAergic neurons, indicating that VGluT2 expressing neurons constitute a population of VTA glutamatergic neurons different to the previously identified DAergic and GABAergic neurons. In vitro (Cameron et al., 1997) and in vivo (Ungless et al., 2004) studies combining electrophysiological and phenotypic characterization of VTA cells indicate that neurons with a neurochemical composition other than those that express DA and GABA are expected to be present in the VTA. It is likely that some, if not all, of these other neurons are glutamatergic.

Although we demonstrated that glutamatergic and DAergic neurons constitute separate populations of cells in the VTA of adult rats, several lines of evidence indicate that some midbrain DAergic neurons in culture (Sulzer et al., 1998; Bourque & Trudeau, 2000; Joyce & Rayport, 2000; Sulzer & Rayport, 2000; Rayport, 2001; Congar et al., 2002; Dal Bo et al., 2004) and DAergic neurons in the caudal linear nucleus (Kawano et al., 2006) may display a glutamatergic phenotype. Moreover, based on recent results by Trudeau and coworkers showing that VGluT2 mRNA and protein are expressed in midbrain DAergic neurons in culture (Dal Bo et al., 2004), it was hypothesized that changes in regulation of expression of VGluT2 in DAergic neurons may play a role in pathophysiological processes in schizophrenia, Parkinson’s disease and drug abuse.

Functional significance of VTA glutamatergic neurons

To determine the role that the glutamatergic neurons located in the VTA may play in brain function, it is necessary to identify the synaptic circuitries in which these neurons participate and to determine whether they regulate excitatory neurotransmission within the VTA as interneurons or outside the VTA as projection neurons.

VTA glutamatergic neurons as interneurons

While here we demonstrated that glutamatergic neurons are present in the VTA, further studies are necessary to determine if local DAergic or GABAergic neurons regulate VTA glutamatergic neurons. Alternatively, VTA glutamatergic neurons may participate in the excitatory regulation of local DAergic or GABAergic neurons. The VTA receives glutamatergic innervations from different sources (reviewed in Meltzer et al., 1997), such as the prefrontal cortex (Carter, 1982; Kornhuber et al., 1984; Sesack & Pickel, 1992), subthalamic nucleus (Kita & Kitai, 1987; Rinvik & Ottersen, 1993), pedunculopontine nucleus (Tokuno et al., 1988) and the ventral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (Georges & Aston-Jones, 2002). While electrophysiological studies show that VTA principal neurons have spontaneous burst firing in the intact animal, this property is not found in principal neurons on in vitro slide preparations (Johnson & North, 1992). Thus these studies underscore the importance of glutamatergic inputs to principal neurons in the control of firing, which is lost as a result of slide preparation. However, these observations do not eliminate the possibility that a subset of VTA neurons receive glutamatergic inputs from local glutamatergic neurons.

VTA glutamatergic neurons as projection neurons

A detailed anatomical study by Swanson (1982) establishes that a large number of nondopaminergic VTA cells usually project to the same terminal fields as DAergic neurons. With the exception of GABAergic projections from the VTA to nucleus accumbens (Van Bockstaele & Pickel, 1995) and to prefrontal cortex (Carr & Sesack, 2000;), the nature of VTA nondopaminergic neurons projecting to other brain areas has yet to be established. Based on our findings, we suggest that some of the nondopaminergic projection neurons from the VTA, described by Swanson, are likely to be glutamatergic.

Conclusion

We provide here compelling evidence that glutamatergic neurons are present in the VTA. Moreover, they comprise a third population of neurons that differ from those previously identified as either DAergic or GABAergic. The density of glutamatergic neurons varies across the VTA subregions. The observed differential distribution of glutamatergic neurons in the VTA further indicates that this area is complex in its cell type composition and organization.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Abbreviations

- DA

dopamine

- GABA

γ-amino butyric acid

- GAD

glutamic acid decarboxylase

- PB

phosphate buffer

- PBP

parabrachial pigmental area

- PIF

parainterfasicular nucleus

- PN

paranigral nucleus

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- VgluT

vesicular glutamate transporter

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

- VTAR

ventral tegmental area rostral.

References

- Bai L, Xu H, Collins JF, Ghishan FK. Molecular and functional analysis of a novel neuronal vesicular glutamate transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:36764–36769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104578200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellocchio EE, Hu H, Pohorille A, Chan J, Pickel VM, Edwards RH. The localization of the brain-specific inorganic phosphate transporter suggests a specific presynaptic role in glutamatergic transmission. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:8648–8659. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08648.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellocchio EE, Reimer RJ, Fremeau RT, Jr, Edwards RH. Uptake of glutamate into synaptic vesicles by an inorganic phosphate transporter. Science. 2000;289:957–960. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourque MJ, Trudeau LE. GDNF enhances the synaptic efficacy of dopaminergic neurons in culture. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12:3172–3180. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron DL, Wessendorf MW, Williams JT. A subset of ventral tegmental area neurons is inhibited by dopamine, 5-hydroxytryptamine and opioids. Neuroscience. 1997;77:155–166. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00444-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DB, Sesack SR. GABA-containing neurons in the rat ventral tegmental area project to the prefrontal cortex. Synapse. 2000;38:114–123. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(200011)38:2<114::AID-SYN2>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CJ. Topographical distribution of possible glutamatergic pathways from the frontal cortex to the striatum and substantia nigra in rats. Neuropharmacology. 1982;21:379–383. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(82)90019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congar P, Bergevin A, Trudeau LE. D2 receptors inhibit the secretory process downstream from calcium influx in dopaminergic neurons: implication of K+ channels. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;87:1046–1056. doi: 10.1152/jn.00459.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Bo G, St-Gelais F, Danik M, Williams S, Cotton M, Trudeau LE. Dopamine neurons in culture express VGLUT2 explaining their capacity to release glutamate at synapses in addition to dopamine. J. Neurochem. 2004;88:1398–1405. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremeau RT, Jr, Burman J, Qureshi T, Tran CH, Proctor J, Johnson J, Zhang H, Sulzer D, Copenhagen DR, Storm-Mathisen J, Reimer RJ, Chaudhry FA, Edwards RH. The identification of vesicular glutamate transporter 3 suggests novel modes of signaling by glutamate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:14488–14493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222546799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremeau RT, Jr, Troyer MD, Pahner I, Nygaard GO, Tran CH, Reimer RJ, Bellocchio EE, Fortin D, Storm-Mathisen J, Edwards RH. The expression of vesicular glutamate transporters defines two classes of excitatory synapse. Neuron. 2001;31:247–260. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiyama F, Furuta T, Kaneko T. Immunocytochemical localization of candidates for vesicular glutamate transporters in the rat cerebral cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 2001;435:379–387. doi: 10.1002/cne.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georges F, Aston-Jones G. Activation of ventral tegmental area cells by the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis: a novel excitatory amino acid input to midbrain dopamine neurons. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:5173–5187. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-05173.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA, Onn SP. Morphology and electrophysiological properties of immunocytochemically identified rat dopamine neurons recorded in vitro. J. Neurosci. 1989;9:3463–3481. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-10-03463.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gras C, Herzog E, Bellenchi GC, Bernard V, Ravassard P, Pohl M, Gasnier B, Giros B, El Mestikawy S. A third vesicular glutamate transporter expressed by cholinergic and serotoninergic neurons. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:5442–5451. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05442.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M, Otsuka M, Morimoto R, Hirota S, Yatsushiro S, Takeda J, Yamamoto A, Moriyama Y. Differentiation-associated Na+-dependent inorganic phosphate cotransporter (DNPI) is a vesicular glutamate transporter in endocrine glutamatergic systems. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:43400–43406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106244200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog E, Bellenchi GC, Gras C, Bernard V, Ravassard P, Bedet C, Gasnier B, Giros B, El Mestikawy S. The existence of a second vesicular glutamate transporter specifies subpopulations of glutamatergic neurons. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:RC181. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-j0001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. Regional differences within the rat ventral tegmental area for muscimol self-infusions. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1998;61:87–92. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SW, North RA. Two types of neurone in the rat ventral tegmental area and their synaptic inputs. J. Physiol. 1992;450:455–468. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce MP, Rayport S. Mesoaccumbens dopamine neuron synapses reconstructed in vitro are glutamatergic. Neuroscience. 2000;99:445–456. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano M, Kawasaki A, Sakata-Haga H, Fukui Y, Kawano H, Nogami H, Hisano S. Particular subpopulations of midbrain and hypothalamic dopamine neurons express vesicular glutamate transporter 2 in the rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2006;498:581–592. doi: 10.1002/cne.21054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita H, Kitai ST. Efferent projections of the subthalamic nucleus in the rat: light and electron microscopic analysis with the PHA-L method. J. Comp. Neurol. 1987;260:435–452. doi: 10.1002/cne.902600309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornhuber J, Kim JS, Kornhuber ME, Kornhuber HH. The cortico-nigral projection: reduced glutamate content in the substantia nigra following frontal cortex ablation in the rat. Brain Res. 1984;322:124–126. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)91189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Moal M, Simon H. Mesocorticolimbic dopaminergic network: functional and regulatory roles. Physiol. Rev. 1991;71:155–234. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer LT, Christoffersen CL, Serpa KA. Modulation of dopamine neuronal activity by glutamate receptor subtypes. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1997;21:511–518. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales M, Bloom F. The 5-HT3 receptor is present in defferent subpopulations of GABAergic neurons in the rat telencephalon. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:3157–3167. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-09-03157.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson VG, Zabetian CP, Bolanos CA, Edwards S, Barrot M, Eisch AJ, Hughes T, Self DW, Neve RL, Nestler EJ. Regulation of drug reward by cAMP response element-binding protein: evidence for two functionally distinct subregions of the ventral tegmental area. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:5553–5562. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0345-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Amsterdam; Boston: Elsevier Academic Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson OT. The cytoarchitecture of the interfascicular nucleus and ventral tegmental area of Tsai in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1979a;187:85–98. doi: 10.1002/cne.901870106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson OT. A Golgi study of the ventral tegmental area of Tsai and interfascicular nucleus in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1979b;187:99–115. doi: 10.1002/cne.901870107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayport S. Glutamate is a cotransmitter in ventral midbrain dopamine neurons. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2001;7:261–264. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8020(00)00068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinvik E, Ottersen OP. Terminals of subthalamonigral fibres are enriched with glutamate-like immunoreactivity: an electron microscopic, immunogold analysis in the cat. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 1993;6:19–30. doi: 10.1016/0891-0618(93)90004-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd ZA, Bell RL, Kuc KA, Zhang Y, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. Intracranial self-administration of cocaine within the posterior ventral tegmental area of Wistar rats: evidence for involvement of serotonin-3 receptors and dopamine neurons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005;313:134–145. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.075952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer MK, Varoqui H, Defamie N, Weihe E, Erickson JD. Molecular cloning and functional identification of mouse vesicular glutamate transporter 3 and its expression in subsets of novel excitatory neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:50734–50748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206738200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1–27. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Getting formal with dopamine and reward. Neuron. 2002;36:241–263. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00967-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesack SR, Pickel VM. Prefrontal cortical efferents in the rat synapse on unlabeled neuronal targets of catecholamine terminals in the nucleus accumbens septi and on dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area. J. Comp. Neurol. 1992;320:145–160. doi: 10.1002/cne.903200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Weiss F. The dopamine hypothesis of reward: past and current status. TINS. 1999;22:521–527. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Joyce MP, Lin L, Geldwert D, Haber SN, Hattori T, Rayport S. Dopamine neurons make glutamatergic synapses in vitro. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:4588–4602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04588.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Rayport S. Dale’s principle and glutamate corelease from ventral midbrain dopamine neurons. Amino Acids. 2000;19:45–52. doi: 10.1007/s007260070032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW. The projections of the ventral tegmental area and adjacent regions: a combined fluorescent retrograde tracer and immunofluorescence study in the rat. Brain Res. Bull. 1982;9:321–353. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(82)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamori S, Rhee JS, Rosenmund C, Jahn R. Identification of a vesicular glutamate transporter that defines a glutamatergic phenotype in neurons. Nature. 2000;407:189–194. doi: 10.1038/35025070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamori S, Rhee JS, Rosenmund C, Jahn R. Identification of differentiation-associated brain-specific phosphate transporter as a second vesicular glutamate transporter (VGLUT2) J. Neurosci. 2001;21:RC182. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuno H, Moriizumi T, Kudo M, Nakamura Y. A morphological evidence for monosynaptic projections from the nucleus tegmenti pedunculopontinus pars compacta (TPC) to nigrostriatal projection neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 1988;85:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90417-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungless MA, Magill PJ, Bolam JP. Uniform inhibition of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area by aversive stimuli. Science. 2004;303:2040–2042. doi: 10.1126/science.1093360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Pickel VM. GABA-containing neurons in the ventral tegmental area project to the nucleus accumbens in rat brain. Brain Res. 1995;682:215–221. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00334-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varoqui H, Schafer MK, Zhu H, Weihe E, Erickson JD. Identification of the differentiation-associated Na+/PI transporter as a novel vesicular glutamate transporter expressed in a distinct set of glutamatergic synapses. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:142–155. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00142.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SM, Goldman-Rakic PS. Widespread origin of the primate mesofrontal dopamine system. Cereb. Cortex. 1998;8:321–345. doi: 10.1093/cercor/8.4.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:483–494. doi: 10.1038/nrn1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangen A, Ikemoto S, Zadina JE, Wise RA. Rewarding and psychomotor stimulant effects of endomorphin-1: anteroposterior differences within the ventral tegmental area and lack of effect in nucleus accumbens. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:7225–7233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-07225.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]