Abstract

This investigation first examined the incremental validity of distress tolerance in terms of alcohol use coping motives within a trauma-exposed community sample of adults, beyond the variance contributed by posttraumatic stress symptom severity, difficulties in emotion regulation, alcohol consumption, and other (noncriterion) alcohol use motives. Secondly, the potential mediating role of distress tolerance in the association between posttraumatic stress symptom severity and alcohol use coping motives was tested. Participants were 83 community-recruited individuals (63.8% women; Mage = 22.98, SD = 9.24) who endorsed exposure to at least one traumatic life event and past-month alcohol use. Participants were assessed using structured diagnostic interviews and a series of self-report inventories. Results were consistent with hypotheses, because distress tolerance was significantly and incrementally associated with alcohol use coping motives; and distress tolerance at least partially mediated the association between posttraumatic stress and alcohol use coping motives. Theoretical and clinical implications as well as future directions regarding the association between distress tolerance and alcohol use motives among trauma-exposed persons are discussed.

Keywords: distress tolerance, alcohol, trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder

The frequent co-occurrence of trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)with alcohol use problems has been well documented (Langeland & Hartgers, 1998; McFarlane, 1998; McFarlane et al., 2009; Stewart, 1996). Epidemiological studies have found that approximately 51.9% of men and 27.9% of women with lifetime PTSD also meet criteria for lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence, as compared to 24.7% of men and 10.5% of women without lifetime PTSD (Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995). Conversely, alcohol use disorders have been related to more severe posttraumatic stress symptoms in trauma-exposed samples both with and without the PTSD diagnosis (Back, Sonne, Killeen, Dansky, & Brady, 2003; Stewart, Conrod, Pihl, & Dongier, 1999).

One initial line of work, focused on better understanding the mechanisms underlying the co-occurrence of these clinical problems, has indicated that trauma-exposed individuals with and without PTSD may demonstrate an enhanced motivation to drink alcohol to cope with negative affective states (Dixon, Leen-Feldner, Ham, Feldner, & Lewis, 2009; Stewart, Conrod, Samoluk, Pihl, & Dongier, 2000; Stewart, Mitchell, Wright, & Loba, 2004; Ullman, Filipas, Townsend, & Starzynski, 2006). Consistent with this perspective, self-reported drinking to cope with negative affect is significantly associated with severity of PTSD symptoms (Ullman et al., 2005). Other work has found that trauma-exposed individuals with alcohol dependence report increased alcohol cravings in the presence of trauma cues (Coffey et al., 2002), suggesting that trauma cues and related negative affect may serve as conditioned stimuli for alcohol use. Despite evidence of relations between posttraumatic stress symptoms, defined broadly, and coping motives for alcohol use, the potential mechanisms underlying this association remain unclear.

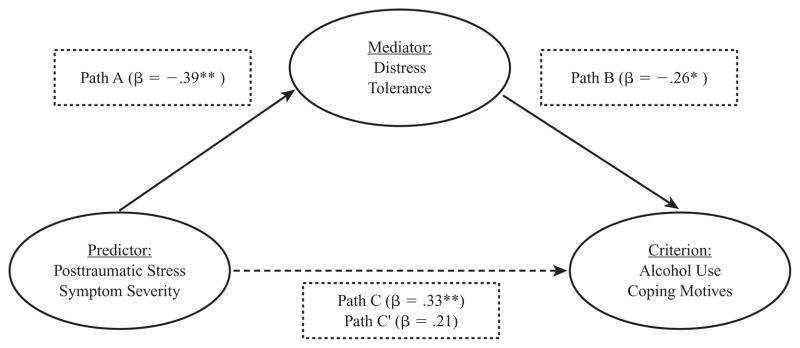

Distress tolerance is a promising construct worthy of further empirical attention within this realm because of its documented associations with both alcohol use (Daughters, Lejuez, Kahler, Strong, & Brown, 2005; Simons & Gaher, 2005) and posttraumatic stress (Vujanovic, Bernstein, & Litz, 2011). Distress tolerance is defined as the perceived ability to withstand emotional distress (Simons & Gaher). Distress tolerance has been inversely associated with (a) increased alcohol use and related coping motives (Buckner, Keough, & Schmidt, 2007; Simons & Gaher; Simons, Gaher, Oliver, Bush, & Palmer, 2005) as well as (b) elevated post-traumatic stress symptoms (Marshall-Berenz, Vujanovic, Bonn-Miller, Bernstein, & Zvolensky, 2010; Vujanovic, Bernstein, et al., 2011; Vujanovic, Bonn-Miller, Potter, Marshall-Berenz, & Zvolensky, 2011). Although empirically unclear, it is possible that greater posttraumatic stress symptoms may contribute to lower levels of tolerance for distressing emotions. Such lower distress tolerance, in turn, may contribute to increased motivation to use alcohol to cope with negative mood states. As of yet, it is empirically uncertain whether distress tolerance is related to coping motives for alcohol use among trauma-exposed individuals, or whether such a relation is better explained by other factors known to co-occur with alcohol use problems and posttraumatic stress (e.g., difficulties in regulating emotion). Furthermore, no empirical work has attempted to investigate the mediational model described previously wherein distress tolerance partially explains the association between posttraumatic stress symptom severity and coping motives for alcohol use (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed model: Distress tolerance as mediator of the association between posttraumatic stress symptom severity and alcohol use coping motives.

Note. Path A: association between predictor and mediator; Path B: association between mediator and criterion; Path C: association between predictor and criterion; Path C′: association between predictor and criterion, after controlling for the mediator. Path A: no covariates were included; Path B/C′: covariates included alcohol consumption level and the noncriterion alcohol use motives; Path C: covariates included alcohol consumption level and the noncriterion alcohol use motives.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

Together, the present investigation sought to extend the existing literature with two lines of related inquiry. First, the incremental validity of distress tolerance in terms of alcohol use coping motives, within a trauma-exposed community sample of adults, was examined. It was hypothesized that distress tolerance, as indexed by the Distress Tolerance Scale (Simons & Gaher, 2005), would be incrementally (inversely) associated with alcohol use coping motives, beyond the variance contributed by posttraumatic stress symptom severity, difficulties in emotion regulation, alcohol consumption, and other (noncriterion) alcohol use motives. Alcohol consumption (cf. alcohol use problem severity) was selected as a covariate because the sample was not composed of individuals with alcohol use problems, exclusively. Moreover, this approach to measuring alcohol is consistent with past research and therefore facilitates greater comparability across extant work (Stewart et al., 1999). Based on past work (e.g., Simons & Gaher), significant associations were not expected between distress tolerance and noncoping alcohol use motives (i.e., Social, Enhancement, Conformity motives). Second, contingent on a significant incremental association between distress tolerance and alcohol use coping motives, the potential mediating role of distress tolerance in the relation between posttraumatic stress symptom severity and alcohol use coping motives was explored. Here, it was hypothesized that distress tolerance would mediate the association between posttraumatic stress symptom severity and alcohol use coping motives.

Method

Participants

Eighty-three individuals (63.8% women; Mage = 22.98, SD = 9.24), recruited from the community of greater Burlington, Vermont, participated in the study. All participants reported exposure to at least one traumatic life event, meeting PTSD Criteria A1 and A2 (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000), as indexed by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al., 1995). All participants also reported alcohol use within the past month to ascertain current drinking behavior. The racial/ethnic composition of the sample was consistent with that of the state of Vermont (State of Vermont, Department of Health, 2007): Approximately 96.4% of participants identified as White, 1.2% identified as Asian, 1.2% identified as Hispanic/Latino, and 1.2% identified as biracial. Two-thirds of the sample completed some college, 19.3% completed high school/GED, 9.6% completed college, and 4.8% completed a graduate degree.

Participants endorsed at least one traumatic event on the CAPS Life Events Checklist (Blake et al., 1995), reporting an average of 7.81 (SD = 6.14) lifetime traumatic events (please see CAPS description in the “Measures” section for definition of “traumatic event”). The CAPS was administered with reference to participants’ self-reported “worst” traumatic event, which also met DSM-IV PTSD Criterion A. With regard to participants’ reports of “worst” traumatic event, 20.5% reported a sudden, unexpected death; 14.5% reported a sexual assault; 14.5% reported a transportation accident; 9.6% reported a life-threatening illness/injury; 7.2% reported a sudden, violent death; 6.0% reported a physical assault; 6.0% reported a serious accident; 4.8% reported an unwanted sexual experience; 3.6% reported a natural disaster; 1.2% reported a fire/explosion; 1.2% reported assault with a weapon; and 9.6% reported “other” (e.g., unexpected death of a family member or friend). Data related to trauma type were coded as missing for one participant (1.2%).

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders–Nonpatient Version (SCID-I/NP; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995) was administered to index current (past month) Axis I psychopathology. Approximately 47% of participants met diagnostic criteria for a current Axis I disorder, as determined by SCID-I/NP and CAPS administrations. On average, participants met diagnostic criteria for 1.59 (SD = 1.87) current (past month) disorders. According to the CAPS, approximately 4.8% (n = 4) of participants met criteria for PTSD.

As assessed by the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor, de la Fuente, Saunders, & Grant, 1992), 60.3% of the total sample reported drinking at least two to three times per week, with 34.9% reporting drinking at least five to six drinks, on average, per occasion. Participants scored an average of 10.27 (SD = 6.61) on the AUDIT, indicating at least moderate alcohol problems (i.e., AUDIT score of 8 or greater; Babor et al., 1992).

The current study data were collected as part of a larger laboratory investigation focused on emotion. Exclusionary criteria for the primary investigation included current psychotropic medication use, lifetime panic disorder diagnosis, psychosis, current suicidal ideation, limited mental competency, and the inability to provide written informed consent.

Measures

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV—Nonpatient Version

The SCID-I/NP (First et al., 1995) was administered to assess current (past month) Axis I psychopathology, current (past 6 months) substance use disorders, and current (past month) suicidal ideation (see exclusionary criteria). In this study, each SCID administration was reviewed by the principal investigator to ensure interrater agreement.

Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale

The CAPS (Blake et al., 1995) was employed to measure the frequency and intensity of current (past month) posttraumatic stress symptoms as well as to assess current (past month) PTSD diagnostic status. All individuals met the DSM-IV-TR PTSD Criterion A (i.e., the event “involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others,” and the trauma response “involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror”; APA, 2000, p. 467). The CAPS Life Events Checklist was used to index number of traumatic events; all degrees of exposure (i.e., “happened to me,” “witnessed it,” “learned about it”) were included to include a comprehensive index of past life stressors. Consistent with prior research (Weathers, Ruscio, & Keane, 1999), symptom severity was defined as the sum of the frequency and intensity ratings. The CAPS is considered a “gold standard” for indexing PTSD diagnostic status as well as symptom severity and has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties (Weathers et al., 1999). In this study, each CAPS administration was conducted by trained clinical assessors and reviewed by the principal investigator to ensure agreement on posttraumatic stress symptom ratings and diagnosis. No disagreements between the CAPS interviewers and the principal investigator were observed.

Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS)

The DTS (Simons & Gaher, 2005) is a 15-item self-report measure on which respondents indicate, on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree ), the extent to which they believe they can experience and withstand distressing emotional states. The DTS encompasses four types of emotional distress items including (a) perceived ability to tolerate emotional distress (e.g., “I can’t handle feeling distressed or upset”), (b) subjective appraisal of distress (e.g., “My feelings of distress or being upset are not acceptable”), (c) attention absorption by negative emotions (e.g., “When I feel distressed or upset, I cannot help but concentrate on how bad the distress actually feels”), and (d) regulation efforts to alleviate distress (e.g., “When I feel distressed or upset I must do something about it immediately”). High levels of distress tolerance are indicated by higher scores on the DTS (Simons & Gaher). As in past work (e.g., Anestis, Selby, Fink, & Joiner, 2007), the DTS total score was employed as a global index of perceived distress tolerance.

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS)

The DERS (Gratz & Roemer, 2004) is a 36-item self-report measure on which respondents indicate, on a 5-point Likert-style scale (1 = almost never to 5 = almost always), how often each item applies to them. The DERS is multidimensional in that it is comprised of six factors in addition to a total score. These factors are (a) nonacceptance of emotional responses, (b) difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior, (c) impulse control difficulties, (d) lack of emotional awareness, (e) limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and (f) lack of emotional clarity. The DERS has high levels of internal inconsistency (α = .93) and adequate test–retest reliability over a 4–8 week period (r = .88; Gratz & Roemer). Similar to past work (Vujanovic, Zvolensky, & Bernstein, 2008), in the present investigation, we used the DERS total score, a sum of all the items, because this represents a global composite index of difficulties regulating emotion (Gratz & Roemer).

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

The AUDIT (Babor et al., 1992) is a 10-item self-report screening measure developed by the World Health Organization to identify individuals with alcohol use problems. There is a large body of literature attesting to the psychometric properties of the AUDIT (e.g., Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993). The current study used (a) a composite of the frequency and quantity items (items 1 and 2) to index alcohol consumption, and (b) the total score to measure alcohol use problems (Babor et al.). Individuals scoring an 8 or higher on the AUDIT total likely meet criteria for at least “moderate” alcohol problems (Babor et al.).

Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (DMQ-R)

The DMQ-R (Cooper, 1994) is a 20-item self-report measure designed to index reasons why people might be motivated to drink alcohol. Participants rate, on a 5-point Likert-style scale (1 = almost never/never to 5 = almost always/always), how frequently each of the listed reasons motivate them to drink alcohol. Participants estimate relative frequency of drinking, over the past 90 days, for each listed reason. Each subscale score reflects one motive that is tapped by five summated items. The measure yields four scale scores reflecting different motives for drinking alcohol: (a) Coping (i.e., “to forget your worries”), (b) Social (i.e., “because it improves parties and celebrations”), (c) Enhancement (i.e., “because you like the feeling”), and (d) Conformity (i.e., “because your friends pressure you to drink”). The DMQ-R demonstrates good structural and criterion validity, as well as high internal consistency, with alpha values for each subscale ranging from .81 to .94 (Cooper, 1994; MacLean & Lecci, 2000).

Procedure

Individuals who responded to advertisements about a study on emotion were scheduled for a session in the laboratory to determine eligibility and to collect study data. Upon arrival to the laboratory, interested participants first provided verbal and written informed consent. The SCID-I/NP was then administered to determine eligibility based on the criteria identified earlier. Eligible participants were then administered the CAPS and completed a battery of self-report measures. Participants were then compensated $10 for completion of the clinical interviews and self-report measures.

Data Analytic Plan

First, a series of zero-order correlations were conducted to examine associations among variables of primary theoretical interest. Because distress tolerance was not associated with other alcohol use motives at the zero-order level (see Table 1), no corresponding hierarchical regression analyses were conducted. Second, hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine the incremental validity of distress tolerance in terms of coping alcohol use motives, specifically. At Step 1, posttraumatic stress symptom severity (CAPS total score), difficulties in emotion regulation (DERS total score), and alcohol consumption (AUDIT frequency × quantity composite) were entered. At Step 2, the noncriterion alcohol use motives were entered. At Step 3, distress tolerance (DTS total score) was entered. The criterion variable was Coping alcohol use motives (DMQ-R: Coping scale). The purpose of the present model was to document the incremental power of distress tolerance in terms of alcohol use coping motives.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Zero-Order Correlations

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | Mean (SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CAPS total scores | 1 | .42** | .28* | .41** | 2.39** | .45** | .16 | .02 | .10 | 13.48 (16. |

| 2. DERS total scores | — | 1 | 2.07 | .07 | 2.78** | .37** | .22* | .05 | .16 | 82.79 (24. |

| 3. Alcohol consumption | — | — | 1 | .78** | .15 | .18 | 2.36** | .36** | 2.10 | 6.08 (4.13) |

| 4. AUDIT total scores | — | — | — | 1 | 2.04 | .38** | .27* | .33** | .08 | 10.27 (6.61) |

| 5. DTS total scores | — | — | — | — | 1 | 2.45** | 2.18 | 2.13 | 2.18 | 3.38 (.91) |

| 6. DMQ-Coping | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | .34** | .31** | .30** | 10.06 (4.96) |

| 7. DMQ-Social | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | .68** | .20 | 16.71 (5.16) |

| 8. DMQ-Enhancement | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | .06 | 14.68 (5.02) |

| 9. DMQ-Conformity | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 6.89 (2.77) |

Note. CAPS = total posttraumatic stress symptom severity score (frequency + intensity; Blake et al., 1995); DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale total score (Gratz & Roemer, 2004); alcohol consumption = quantity × frequency (AUDIT; Babor et al., 1992); AUDIT total scores = alcohol use problems (Babor et al.); DTS = Total Distress Tolerance Scale score (Simons & Gaher, 2005); DMQ-Social = Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (Social motives subscale); DMQ-Coping = Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (Coping motives subscale); DMQ-Enhancement = Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (Enhancement motives subscale); DMQ-Conformity = Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (Conformity motives subscale; Cooper, 1994).

p < .05.

p < .01.

Third, the mediating role of distress tolerance in the relation between posttraumatic stress symptoms and alcohol use coping motives was examined, using Baron and Kenny’s (1986) recommended test of mediation. Specifically, the test requires the following series of multiple regressions: (a) the predictor variable (i.e., CAPS total score) must significantly predict the criterion variable (i.e., Coping motives); (b) the predictor variable must significantly predict the mediator (i.e., DTS total score); and (c) when the predictor and mediator are entered simultaneously into a third multiple regression, the mediator must significantly predict the criterion variable, and the relation between the predictor and criterion variables is either diminished (partial mediation) or nonexistent (full mediation). In the current mediational test, alcohol consumption level and noncriterion alcohol use motives were entered at Step 1 of the regression equations when Coping alcohol use motives was the criterion variable. No other covariates were employed in this mediational model because they were not theoretically pertinent to the relevant tests.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Zero-Order Correlations

See Table 1 for descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations among study variables. CAPS total symptom severity was significantly positively related to Coping alcohol use motives (r = .45, p < .01), but not to other alcohol use motives. DERS total score was significantly positively related to Social (r = .22, p < .05) and Coping (r = .37, p < .01) alcohol use motives. Additionally, DERS total score was significantly negatively related to DTS total score (r = −.78, p < .01; 60% shared variance). Alcohol consumption was significantly positively related to Social (r = .36, p < .01) and Enhancement (r = .36, p < .01) alcohol use motives. As expected, DTS total score was significantly negatively related to Coping motives (r = −.45, p < .01), but not to other alcohol use motives. Given the nonsignificant zero-order associations between DTS total score and Social, Enhancement, and Conformity motives (ps > .05), corresponding hierarchical regressions analyses, with each motive entered as a criterion variable, were not conducted.

Incremental Association Between Distress Tolerance Scale and Alcohol Use Coping Motives

The model significantly accounted for 40.7% of variance with regard to Coping alcohol use motives, F(7, 82) = 7.35, p < .001. Step 1 of the model significantly accounted for 25.2% of variance in Coping alcohol use motives (p < .001), with CAPS total symptom severity (t = 2.83, β = .32, sr2 = .08, p < .01) and DERS total score (t = 2.19, β = .24, sr2 = .04, p < .05) demonstrating significant associations. Step 2 of the model significantly contributed an additional 11.9% of variance (p < .01), with Conformity alcohol use motives (t = 2.26, β = .22, sr2 = .04, p < .05) demonstrating a significant association. Step 3 of the model significantly accounted for an additional 3.5% of variance in Coping alcohol use motives (p < .05), with DTS total score (t = −2.11, β = −.32, sr2 = .04, p < .05) demonstrating a significant incremental association.

Distress Tolerance as Mediator of the Association Between Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms and Alcohol Use Coping Motives

Path C

A linear regression was conducted with CAPS total score predicting alcohol use coping motives (Figure 1, Path C). Alcohol consumption level and noncriterion alcohol use motives were entered into Step 1 of the regression model as covariates; and CAPS total score was entered into Step 2 of the regression model. The proposed model for the first step of mediation testing (see earlier discussion) was significant, F(5, 84) = 7.87, p < .001. Step 1 of the model contributed a significant 24.1% of variance in Coping motives (p < .001), with the covariate of Conformity alcohol use motives being a significant predictor (t = 2.65, β = .27, sr2 = .07, p < .05). Step 2 of the model accounted for an additional 9.1% of variance (p < .01), with CAPS total score being a significant predictor (t = 3.29, β = .33, sr2= .09, p < .01).

Path A

A linear regression was conducted with CAPS total score predicting DTS total score (Figure 1, Path A). The proposed model for the second step of mediation testing (see earlier discussion) was significant, F1, 80 = 14.28, p < .001. CAPS total score accounted for a significant 15.3% of variance in DTS total score, such that the CAPS total score was inversely related to the DTS total score (t = −3.78, β = −.39, sr2= .15, p < .001).

Path B/C′

A linear regression was conducted to determine both the relation between the DTS total score and alcohol use Coping motives (Figure 1, Path B), as well as to determine the mediating role of DTS total score in the relation between CAPS total score (predictor) and alcohol use Coping motives (criterion; Figure 1, Path C). Here, alcohol consumption level and the non-criterion alcohol use motives were entered into Step 1 of the regression, and CAPS total score and DTS total score were entered simultaneously at Step 2. The proposed model significantly predicted alcohol use Coping motives, F(6, 79) = 8.03, p < .001. Step 1 of the model significantly accounted for 25.2% of variance (p < .001), with alcohol use Conformity motives being a significant predictor (t = 2.93, β = .31, sr2 = .08, p < .01). Step 2 of the model significantly accounted for an additional 14.5% of variance (p < .001), with DTS total score being a significant predictor (t = −2.49, β = −.26, sr2 = .05, p < .05) and CAPS total score evidencing a trend toward statistical significance (t = 1.90, β = .21, sr2 = .03, p = .06). Notably, DTS total score (the mediator) was significantly related to alcohol use coping motives even after taking CAPS total score into account. In addition, the relation between CAPS total score and alcohol use coping motives diminished substantially with the inclusion of DTS total score in the model (sr2 decreased from .09 to .03). CAPS total score evidenced only a trend toward statistical significance when entered simultaneously with DTS total score (p = .06). These findings suggest that DTS total score at least partially mediated the relation between CAPS total score and Coping alcohol use motives. The Sobel test demonstrated consistency with this effect (z = −2.21, p < .05).

One method of further strengthening the interpretation of meditational analyses conducted with cross-sectional data is to conduct an additional analysis reversing the proposed mediator and criterion variable (Preacher & Hayes, 2004; Sheets & Braver, 1999; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Here, we evaluated whether alcohol use Coping motives mediated the relation between CAPS total score and DTS total score. Results were not consistent with mediation in this direction as CAPS total score remained a significant predictor of DTS total score after controlling for both alcohol consumption and other alcohol use motives (t = −3.30, β = −.37, sr2= .10, p < .01).

Discussion

The present investigation sought to examine two related lines of inquiry. First, the incremental validity of distress tolerance was examined with regard to alcohol use coping motives. Second, the possible mediating role of distress tolerance in the association between posttraumatic stress symptom severity and alcohol use coping motives was examined.

As predicted, distress tolerance was significantly and incrementally associated with alcohol use coping motives and no other motives for alcohol use. Here, the effect for distress tolerance was evident beyond the approximately 53% of variance contributed by posttraumatic stress symptom severity, difficulties in emotion regulation, alcohol consumption, and other (noncriterion) alcohol use motives. This novel finding therefore documents a concurrent incremental association between distress tolerance and alcohol use coping motives among a trauma-exposed sample, which is not better explained by other variables known to co-occur with alcohol use problems and post-traumatic stress (Simons & Gaher, 2005). Such results may indicate that trauma-exposed alcohol users with a lower perceived ability to withstand emotional distress may be especially likely to use alcohol to cope with negative affective states. The specificity of the effect for alcohol use coping motives is consistent with hypothesis and replicates past work (e.g., Simons & Gaher).

A second set of analyses added further support to the putative role of distress tolerance as an explanatory mechanism in posttraumatic stress–alcohol relations. Namely, consistent with hypotheses, distress tolerance at least partially mediated the association between posttraumatic stress symptom severity and alcohol use coping motives. Although past research has documented the relations between posttraumatic stress symptoms and alcohol use and related coping motives (Dixon et al., 2009; Stewart et al., 2000; Stewart et al., 2004; Ullman et al., 2006)—replicated in this study—no studies to date have documented the role of distress tolerance in this association. This finding indicates that, among trauma-exposed individuals, a lower perceived ability to tolerate emotional distress may at least partially account for the established association between posttraumatic stress symptoms and alcohol use coping motives. Because of the cross-sectional nature of the finding, the temporal order implicit to the mediational model cannot be ascertained. Therefore, prospective replication and extension of this finding is a necessary next scientific step.

Although not a primary aim of the investigation, it is notable that distress tolerance and difficulties in emotion regulation were distinct—although related—factors; they shared 60% of variance with one another. Although past literature has often discussed distress tolerance as a component of emotion regulation (Amstadter, 2008), this investigation at least suggests that the constructs, as assessed by the DTS and DERS, are empirically distinguishable in terms of alcohol use coping motives. Notably, the relations of these two factors with alcohol use coping motives were comparable (sr2 = .04, respectively), suggesting that both emotion regulation difficulties and distress tolerance may be important (malleable) factors to consider with regard to alcohol use coping motives among trauma survivors.

The present findings may have several direct clinical implications. For example, it may be worth investigating whether trauma-exposed individuals with alcohol use problems benefit from targeted intervention strategies that incorporate distress tolerance skills (e.g., distress tolerance component of dialectical behavior therapy; Linehan, 1993). Such interventions might specifically aim to improve an individual’s ability to cope with posttraumatic stress symptoms and related negative mood states without using alcohol. Additionally, given the observed results, it may be useful to explore the role of distress tolerance in other onset and maintenance of alcohol use problems. For instance, it may be advisable to explore the role of distress tolerance among trauma-exposed persons with alcohol use problems in terms of the nature of the abstinence process. If distress tolerance is fundamentally linked to emotional vulnerability, as implied by the alcohol coping motives effect observed here, it might similarly be associated with other emotionally salient aspects of alcohol use (e.g., perception of withdrawal symptoms, abstinence duration).

Several limitations of the current investigation warrant comment. First, the investigation was based on a racially/ethnically homogeneous sample of community-recruited trauma-exposed participants who consumed alcohol to varying degrees. It is important for future work to extend these findings with more diverse samples and clinical populations of trauma survivors (e.g., PTSD patients) struggling with a diverse spectrum of alcohol problems (e.g., alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence). Second, the sample was composed of individuals who experienced various types of trauma; therefore, the specificity of the documented distress tolerance-alcohol use coping motives association concerning certain types of trauma (e.g., sexual assault, military combat) cannot be determined. Replicating this findings with samples recruited using various strategies is therefore warranted. Third, the study used a cross-sectional design and relied on verbal and written self-reports of each of the variables examined. Therefore, temporal order and causality cannot be inferred, and the potential influence of method–variance effects must be considered. This line of inquiry could be strengthened by the implementation of multimethod assessments, such as experimental paradigms and prospective, longitudinal designs, to establish causal relations and more comprehensively index the studied constructs. Finally, although the present mediational test suggests that there may be explanatory merit for a distress tolerance mechanism linking posttraumatic stress symptoms and alcohol use coping motives, it is not necessarily mutually exclusive compared to other pathways. For example, posttraumatic stress symptoms could possibly mediate the relation between distress tolerance and alcohol use coping motives among trauma-exposed persons. This alternative model was not tested in the present report because the present approach was predicated on one specific theoretical perspective and the limited empirical knowledge base in this domain. Future work, building from the present results, may benefit by testing alternative mediational models in efforts to better understand coping-oriented drinking among trauma-exposed individuals. In addition, it may be advisable to explore moderational models wherein the role of distress tolerance may serve to demarcate trauma-exposed individuals at particularly high risk for coping-oriented alcohol use.

Overall, distress tolerance demonstrated both a unique, incremental role in terms of alcohol use coping motives in a trauma-exposed sample, as well as a (partial) mediating role with regard to the relation between posttraumatic stress symptoms and coping motives for alcohol use. This study replicated preliminary findings of the relations between posttraumatic stress symptoms and distress tolerance (Marshall-Berenz et al., 2010; Vujanovic, Bonn-Miller, et al., 2011), and furthermore, underscored the significance of examining the complex roles that distress tolerance may play in the context of posttraumatic stress and substance use disorders (Richards, Daughters, Bornovalova, Brown, & Lejuez, in press; Vujanovic, Bernstein, et al., 2011). Indeed, distress tolerance has emerged as a factor of clinical importance to better understand the associations between posttraumatic stress and alcohol use coping motives among trauma-exposed adults.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted in accordance with all guidelines set forth by Review Board at the University of Vermont. The views expressed here are those of the authors sarily represent those of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

This work was supported, in part, by a National Institute on Mental Health National Award [1 F31 MH080453-01A1] awarded to Erin C. Marshall-Berenz, and several grants [1 R01 DA027533-0, 1 R01 MH076629-01] awarded to Dr. Zvolensky.

Contributor Information

Anka A. Vujanovic, National Center for PTSD-Behavioral Science Division, VA Boston Healthcare System and Boston University School of Medicine.

Erin C. Marshall-Berenz, University of Mississippi Medical Center and University of Vermont.

Michael J. Zvolensky, University of Vermont.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. textdisorders revision. [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter A. Emotion regulation and anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22(2):211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Selby EA, Fink EL, Joiner TE. The multifaceted role of distress tolerance in dysregulated eating behaviors. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(8):718–726. doi: 10.1002/eat.20471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders J, Grant M. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary (WHO Publication No. 92.4) Geneva, Switzerland: World Healthcare Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Back SE, Sonne SC, Killeen T, Dansky BS, Brady KT. Comparative profiles of women with PTSD and comorbid cocaine or alcohol dependence. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29(1):169–189. doi: 10.1081/ada-120018845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, et al. The development of a Clinician-Administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic, Stress. 1995;8(1):75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Keough ME, Schmidt NB. Problematic alcohol and cannabis use among young adults: The roles of depression and discomfort and distress tolerance. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(9):1957–1963. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Saladin ME, Drobes DJ, Brady KT, Dansky BS, Kilpatrick DG. Trauma and substance cue reactivity in individuals with comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and cocaine or alcohol dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;65(2):115–127. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(2):117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Brown RA. Psychological distress tolerance and duration of most recent abstinence attempt among residential treatment-seeking substance abusers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19(2):208–211. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon LJ, Leen-Feldner EW, Ham LS, Feldner MT, Lewis SF. Alcohol use motives among traumatic event-exposed, treatment-seeking adolescents: Associations with posttraumatic stress. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(12):1065–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (nonpatient edition) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26(1):41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langeland W, Hartgers C. Child sexual and physical abuse and alcoholism: A review. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59(3):336–348. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality. disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- MacLean MG, Lecci L. A comparison of models of drinking motives in a university sample. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14(1):83–87. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall-Berenz EC, Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ. Multi-method study of distress tolerance and PTSD symptom severity in a trauma-exposed community sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23:623–630. doi: 10.1002/jts.20568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane AC. Epidemiological evidence about the relationship between PTSD and alcohol abuse: The nature of the association. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23(6):813–825. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane AC, Browne D, Bryant RA, O’Donnell M, Silove D, Creamer M, et al. A longitudinal analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of posttraumatic symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;118(1–3):166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JM, Daughters SB, Bornovalova MA, Brown RA, Lejuez CW. Distress tolerance and substance use disorders. In: Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A, Vujanovic AA, editors. Distress tolerance. New York: Guilford Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption—II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets VL, Braver SL. Organizational status and perceived sexual harassment: Detecting the mediators of a null effect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999;25(9):1159–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(4):422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM. The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motivation and Emotion. 2005;29(2):83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Oliver MNI, Bush JA, Palmer MA. An experience sampling study of associations between affect and alcohol use and problems among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(4):459–469. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State of Vermont, Department of Health. 2007 Retrieved June 30, 2007, from http://www.healthyvermonters.info/

- Stewart SH. Alcohol abuse in individuals exposed to trauma: A critical review. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;120(1):83–112. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Conrod PJ, Pihl RO, Dongier M. Relations between posttraumatic stress symptom dimensions and substance dependence in a community-recruited sample of substance-abusing women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13(2):78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Conrod PJ, Samoluk SB, Pihl RO, Dongier M. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and situation-specific drinking in women substance abusers. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2000;18(3):31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Mitchell TL, Wright KD, Loba P. The relations of PTSD symptoms to alcohol use and coping drinking in volunteers who responded to the Swissair Flight 111 airline disaster. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2004;18(1):51–68. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski LL. Trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder and problem drinking in sexual assault survivors. Journal of Studies on, Alcohol. 2005;66(5):610–619. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski LL. Correlates of comorbid PTSD and drinking problems among sexual assault survivors. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(1):128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Bernstein A, Litz BT. Traumatic stress. In: Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A, Vujanovic AA, editors. Distress tolerance: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. pp. 126–148. [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Potter CM, Marshall-Berenz EC, Zvolensky MJ. An evaluation of the association between distress tolerance and posttraumatic stress within a trauma-exposed sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2011;33:129–135. doi: 10.1007/s10862-010-9209-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. The interactive effects of anxiety sensitivity and emotion dysregulation in predicting anxiety-related cognitive and affective symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32(6):803–817. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Ruscio AM, Keane TM. Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11(2):124–133. [Google Scholar]