Abstract

Prior studies have documented a range of brain changes that occur as a result of healthy aging as well as neural alterations due to profound dysregulation in vascular health such as extreme hypertension, cerebrovascular disease and stroke. In contrast, little information exists about the more transitionary state between the normal and abnormal physiology that contributes to vascular disease and cognitive decline. Specifically, little information exists with regard to the influence of systemic vascular physiology on brain tissue structure in older individuals with low risk for cerebrovascular disease and with no evidence of cognitive impairment. We examined the association between resting blood pressure and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) indices of white matter microstructure in 128 healthy older adults (43–87 years) spanning the normotensive to moderate-severe hypertensive range. Mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) was related to diffusion measures in several regions of the brain with greatest associations in the anterior corpus callosum and lateral frontal, precentral, superior frontal, lateral parietal and precuneus white matter. Associations between white matter integrity and blood pressure remained when controlling for age, when controlling for white matter lesions, and when limiting the analyses to only normotensive, pharmacologically controlled and prehypertensive individuals. Of the diffusion measures examined, associations were strongest between MABP and radial diffusivity which may indicate that blood pressure has an influence on myelin structure. Associations between MABP and white matter integrity followed spatial patterns resembling those often attributed to the effects of chronological age, suggesting that systemic cerebrovascular health may play a role in neural tissue degeneration classically ascribed to aging. These results demonstrate the importance of the consideration of vascular physiology in studies of cognitive and neural aging, and that this significance extends to even the normotensive and medically controlled population. These data additionally suggest that optimal management of blood pressure may require consideration of the more subtle influence of vascular health on neural health in addition to the primary goal of prevention of a major cerebrovascular event.

INTRODUCTION

A substantial literature exists describing the consequences of healthy aging (Kennedy and Raz, 2009a, b; O'Sullivan et al., 2001; Pfefferbaum et al., 2000; Salat et al., 2005a; Salat et al., 2005b; Sullivan et al., 2001; Virta et al., 1999) as well as the impact of age-associated degenerative conditions including cerebrovascular disease, small vessel disease and stroke (de Laat et al., 2011; Gons et al., 2010; O'Sullivan, 2010; Pierpaoli et al., 1996; Pierpaoli et al., 1993) on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measures of cerebral white matter structure. Similarly, important work has attempted to differentiate the effects of aging, vascular disease, and dementia on white matter structure (Lee et al., 2009; Yoshita et al., 2006). Although the effects of age and the effects of vascular disease are typically considered distinct, accumulating evidence suggests that biological factors that simply increase the risk for a cerebrovascular event also exert their own influence on brain tissue. For example, various composite metrics of stroke risk, most notably, the Framingham Stroke Risk Profile (D'Agostino et al., 1994) have been shown to be associated with brain tissue damage (Jeerakathil et al., 2004; Seshadri et al., 2004). The FSRP is a calculated score comprised of several health factors and predicts an individual’s 10 year risk of stroke. Of the risk factors contributing to the FSRP, hypertension is a highly prevalent condition in older adults. Recent estimates suggest that 11% of individuals 65–74 years of age, and 17% of individuals 75 and over are hypertensive (He et al., 2005). Hypertension alone is associated with a range of histopathologic damage (for review see (Manolio et al., 2003)) as well as increased white matter lesion volume measured on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) by white matter signal abnormalities (Longstreth et al., 1996). Given these intersecting factors, the dynamics between age and dementia-associated white matter lesions and microstructural damage has been an active area of investigation (Bastin et al., 2009; Benedetti et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2009). The diagnostic category of hypertension was conceptualized as a metric of risk for a cerebrovascular event. However, the specific diagnostic criteria for hypertension are somewhat arbitrary and more recent consensus groups have created additional classifications such as ‘prehypertension’ (Chobanian et al., 2003), an earlier stage of risk. It is thus unclear if hypertension per se is necessary for blood pressure to affect tissue structure, or if inter-individual variation in blood pressure is alone sufficient to impact neural health. Mild hypertension, controlled hypertension, and normal variation in blood and pulse pressure have all been shown to impact neural tissue (Breteler et al., 1994; DeCarli et al., 1995; Goldstein et al., 1998; Hoptman et al., 2009; Kennedy and Raz, 2009b; Leritz et al.; Raz et al., 2005; Raz et al., 2003). It is possible that this effect is due to slow progressive degenerative processes, as prior studies have demonstrated that blood pressure measured in mid-life is associated with late life white matter lesions (Swan et al., 1998). Overall, these studies are of great interest because they demonstrate that subtle inter-individual variation in systemic physiology may influence neural health in the absence of overt damage due to stroke or other large-scale cerebrovascular incident.

Prior studies have examined the association between blood pressure and white matter integrity in clinical populations (Barrick et al., 2010; Gons et al., 2010; Hannesdottir et al., 2009; Patel and Markus, 2011). However, to date, few studies have reported direct associations between blood pressure and white matter tissue structure measured with imaging procedures such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) in a normative sample. Kennedy and Raz (2009) found an association between pulse pressure and anterior white matter integrity in older normotensive individuals (Kennedy and Raz, 2009b). Similarly, Leritz and colleagues (Leritz et al., 2010a) demonstrated an association between mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) and white matter integrity in the anterior but not posterior corpus callosum in a population of subclinical to mildly hypertensive older African Americans. These findings demonstrate that DTI may provide a sensitive metric of regionally specific tissue damage due to variation in vascular integrity. To date, no studies have described the whole-brain regional associations between blood pressure and white matter tissue structure. Thus, it is unclear whether blood pressure may influence white matter structure outside of the anterior regions described in prior work.

We examined the relationship between MABP and white matter integrity in 128 generally healthy older adults with a focus on individuals in the normotensive to moderately hypertensive range. In contrast to prior work examining individuals categorized as ‘hypertensive’ or ‘normotensive’, we examined MABP as a quantitative variable across the full range of inter-individual variation in this population. We mapped the association between blood pressure and DTI based measures of white matter integrity using complementary voxel-based and region of interest (ROI) procedures. Given the high prevalence of hypertension in older adults, it was hypothesized that blood pressure would be associated with white matter integrity in anterior brain regions, and that patterns would resemble those that have been traditionally ascribed to normal aging such as profound frontal white matter deterioration (O'Sullivan et al., 2001; Pfefferbaum et al., 2000; Salat et al., 2005a; Salat et al., 2005b; Sullivan et al., 2001). In particular, it is possible that myelin damage due to minor ischaemic events would manifest in an association between MABP and radial diffusivity, a putitive marker of myelin damage (Sun et al., 2006). The results demonstrate strong associations between blood pressure and diffusion measures in several regions of the brain that are independent of age and apparent in even mild, controlled hypertensive individuals with a particular sensitivity of the radial diffusivity.

METHODS

Participants

DTI and blood pressure data were acquired on 128 participants (78F/50M). Participants were recruited from two separate but overlapping studies examining how common cerebrovascular risk factors impact brain structure and cognition (Leritz et al., 2010b). Thirty-four participants were recruited through the Harvard Cooperative Program on Aging (HCPA) Claude Pepper Older American Independence Center (OAIC). Participants in this program were recruited from the community in response to an advertisement appearing in the HCPA newsletter asking for healthy community-dwelling older African Americans. Eighty-one participants were recruited through the Understanding Cerebrovascular and Alzheimer’s Risk in the Elderly (UCARE) program, a study investigating how factors relating to cerebrovascular health impact brain structure and cognition, and contribute to the risk for dementia (Leritz et al., 2010b). Participants in this study were recruited through the Boston University Alzheimer’s Disease Center (BUADC) based on the initial criteria of having a first-degree family relative with dementia. Participants were excluded if they had a history of head trauma of mild severity or greater according to the criteria of Fortuny et al. (Fortuny et al., 1980) (e.g., loss of consciousness for greater than 10 minutes), any history of more than one head injury, diagnosis of any form of dementia (i.e., Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia), any severe psychiatric illness, or any history of brain surgery. All participants were literate with at least a 6th grade education. Ninety-two of the participants were right-handed. Mini-mental state examination (MMSE) scores ranged from 23 to 30. These scores are in a range outside of a dementia diagnosis according to normative data for the demographic composition of the sample (Bohnstedt et al., 1994). Demographic and health characteristics of all participants are presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic and Physiological Data

| n = 128 |

Mean (Standard Deviation) |

|---|---|

| Demographic | |

| Age (years) | 67.94 (9.38) |

| Education (years) | 14.83 (2.64) |

| MMSE * | 27.82 (1.82) |

| Blood Pressure | |

| Mean Systolic – Sitting (mm Hg) | 133.09 (18.16) |

| Mean Systolic – Standing (mm Hg) | 128.27 (20.29) |

| Mean Diastolic – Sitting (mm Hg) | 76.20 (9.07) |

| Mean Diastolic - Standing (mm Hg) | 74.57 (10.00) |

| Mean Arterial Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 95.16 (10.73) |

| Serum Cholesterol | |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 202.44 (41.37) |

| Low Density Lipoprotein (mg/dL) | 118.61 (32.89) |

| High Density Lipoprotein (mg/dL) | 61.60 (17.70) |

| Glucose | |

| Glycosylated Hemoglobin - HA1c (%) | 5.8 (0.7) |

| Percent of sample with HA1c above 7.0 | 8/128 (6.25%) |

| Tobacco Use | |

| Smokers/Non Smokers ** | 12/115 (9.45%) |

MMSE = mini-mental status examination (MMSE data were not available on 8 participants)

Smoking status was unavailable for 1 participant.

Table 2.

Demographic and blood pressure measure by medication group*.

| Medicated (N=61) Mean (SD) |

Not Medicated (N=65) Mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age | 70.23 (7.64) | 65.94 (10.49) |

| MMSE score | 27.84 (1.74) | 27.85 (1.91) |

| Mean Systolic – Sitting (mm Hg) | 136.54 (16.06) | 130.08 (19.75) |

| Mean Systolic – Standing (mm Hg) | 133.24 (20.12) | 123.81 (19.80) |

| Mean Diastolic – Sitting (mm Hg) | 77.21 (8.08) | 75.22 (9.99) |

| Mean Diastolic - Standing (mm Hg) | 75.42 (9.94) | 73.80 (10.13) |

| Mean Arterial Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 96.99 (8.97) | 93.50 (12.12) |

2 participants have unknown BP medication status.

Blood pressure measurements

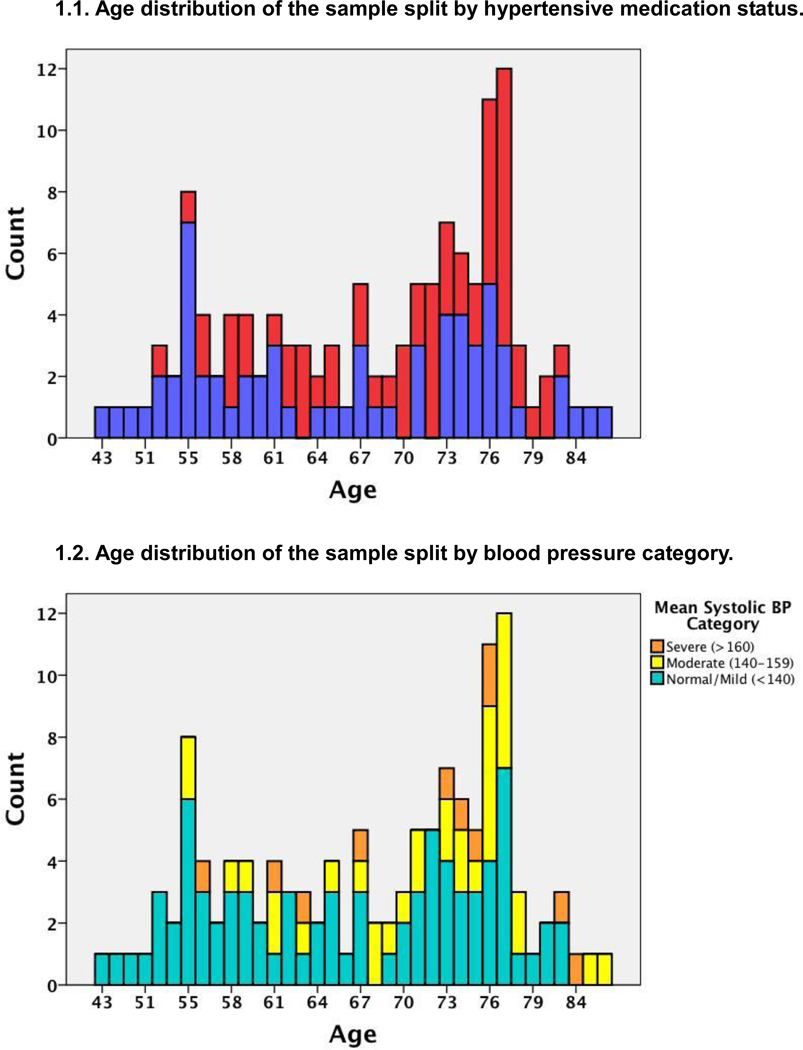

Systolic and diastolic blood pressures (BP) were carefully recorded as the average of four separate measurements to enhance the reliability of the metric. The first measure was acquired in seated position after five minutes of rest with the arm at rest at the level of the heart using a sphygmomanometer. A second measurement was obtained five minutes later and the average of two values was recorded. This same procedure was then repeated in standing position, yielding a total of four BP measurements: seated systolic and diastolic, as well as standing systolic and diastolic. Diagnostic categories followed current conventions of a systolic blood pressure of 120–139 as indicative of “mild” or “pre” hypertension, a systolic BP of 140–159 to be “Stage 1” hypertension, and a systolic BP of 160 or greater to be indicative of “Stage 2” (severe) hypertension. In our sample, thirty (25%) individuals maintained normal systolic levels, and fifty (39%) individuals would be classified as “pre-hypertension”. Thirty-five (27%) would be classified as “Stage 1,” and eleven (9%) would be classified as “Stage 2”. Thus, 82 (64%) would be considered to have normal-mild BP readings (Figure 1). Data were examined across the full range of variation, as well as in subgroups of the non-hypertensive and controlled and mild hypertensive individuals only. Data were examined as the mean arterial blood pressure (MABP = diastolic + (1/3(systolic-diastolic)), as this measure is considered to be the perfusion pressure experienced by organs of the body and thus could be influential in tissue integrity. The distribution of relevant participant demographics is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Age distribution of individuals in the sample split by hypertensive medication usage (1.1) and by blood pressure status (1.2). Medication usage and diagnosis of hypertension was well distributed across the age-range examined.

Medication Usage

Sixty-one individuals (48%) in our sample were taking BP medications (such as beta blockers, ace inhibitors, or calcium channel blockers). To examine the potential influence of medication on the results presented, individuals on and off medication were differentially represented in scatterplots, and medication use was considered in secondary analyses.

DTI acquisition

Global and regional WM integrity was assessed using DTI measures of fractional anisotropy (FA) and axial [L1] and radial [(L2+L3)/2] diffusivity (the parallel and perpendicular diffusivities, respectively). The axial and radial diffusivities were examined as animal models suggest that these different diffusion parameters may be differentially sensitive to myelin and fiber pathology (Budde et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2006). DTI acquisitions were performed with a twice-refocused spin echo single shot echo planar sequence to minimize eddy current-induced image distortions (Reese et al., 2003) (Siemens Avanto; TR/TE=7200/77 ms, b=700 s/mm , acquisition matrix = 128 × 128, 256×256 mm FOV, 2 mm slice thickness with 0-mm gap, 10 T2 + 60 DWI; 64 oblique slices; total acquisition time 8 min 38 sec) in 116 participants. The 60 diffusion weighted directions were obtained using the electrostatic shell method (Jones et al., 1999), providing a high signal-to-noise diffusion volume. Twelve of the participants were imaged early in the study on a Siemens Sonata scanner (TR/TE=9000/68 ms, b=700 s/mm , acquisition matrix = 128 × 128, 256×256 mm FOV, 2 mm slice thickness with 0-mm gap, 8 T2 + 8 averages of 6 DWI). These participants were not found to substantially affect the findings or conclusions from the work and were therefore included in the overall analyses. For all scans, the diffusion tensor was calculated on a voxel-by-voxel basis with conventional reconstruction methods (Basser et al., 1994).

DTI preprocessing and analysis: motion and eddy current correction

Preprocessing was performed with diffusion tools developed at the Martinos Center as part of the Freesurfer software package (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu) as well as tools provided with the FSL processing suite (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/fsl). Diffusion volumes were eddy current and motion corrected using FSL's Eddy Correct tool. The diffusion tensor was calculated for each voxel using a least-squares fit to the diffusion signal. The T2 weighted lowb volume was then skull stripped using FSL's Brain Extraction Tool (BET) (Smith, 2002), and this volume served as a brain-mask for all other diffusion maps. The lowb structural volume was collected using identical sequence parameters as the directional volumes with no diffusion weighting, and was thus in complete register with the final diffusion maps. Maps for fractional anisotropy (FA), axial (DA) and radial (RD) diffusivity were entered in voxel based analyses using the Tract Based Spatial Statistics (TBSS) procedure for inter-participant spatial normalization (Smith et al., 2006).

Nonlinear registration and tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS)

Voxelwise processing of the FA data was carried out using TBSS (Tract-Based Spatial Statistics)(Smith et al., 2006), part of FSL (Smith et al., 2004). In this procedure, all subjects’ FA data were aligned into a common space using the nonlinear registration tool FNIRT (Andersson et al., 2007a; Andersson et al., 2007b) , which uses a b-spline representation of the registration warp field (Rueckert et al., 1999). The TBSS procedure next creates a mean FA image by averaging all participants’ aligned FA maps, and then thresholds this average for voxels with an FA ≥ 0.2 to generate a mean FA skeleton which represents the centers of all tracts common to the group. This use of the FA skeleton helps avoid inclusion of regions that are likely composed of multiple tissue types or fiber orientations and may be susceptible to partial volume contamination. The next step in the TBSS processing is a projection of each participant’s regional diffusion values to the appropriate location on the template skeleton, and this information was entered into voxelwise group statistics. Data along the skeleton were smoothed utilizing an anatomical constraint to limit the smoothing to neighboring data within adjacent voxels along the skeleton. The exact transformations derived for the FA maps were applied to the other diffusion contrast volumes (axial/radial diffusivities) for matched processing of image volumes for each participant. Statistical maps were dilated from the TBSS skeleton for visualization purposes.

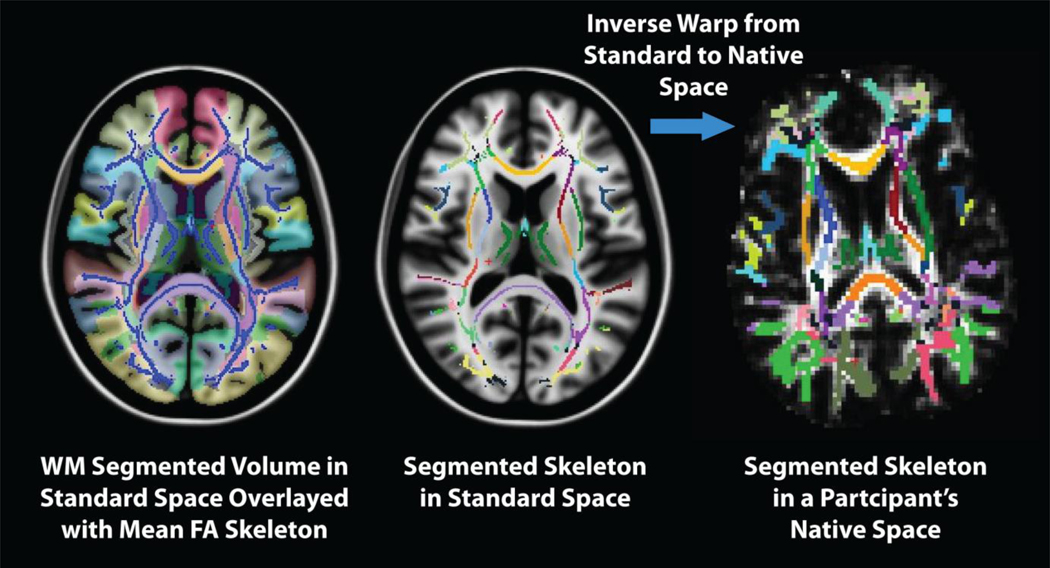

ROI Analysis

Regions of interest (ROIs) limited to the TBSS skeleton were created using the combination of two white matter atlases. The first set of ROIs was generated using the Johns Hopkins University white matter labels, available as part of the FSL suite. The second ROI approach employed T1 -based WM parcellations automatically created during the FreeSurfer processing stream (Salat et al., 2009)(Figure 2). These regional measures were based on gyral folding patterns (Desikan et al., 2006) which were subsequently diffused from the cortex into the subjacent white matter, resulting in a white matter parcellation for each gyral label, unique to each individual's anatomy. Registration of the T1 image to the lowb volume was performed using the FreeSurfer bbregister tool (Greve and Fischl, 2009), a novel procedure that utilizes tissue contrast (gray/white matter) as the basis of the registration cost function. White matter ROI values were extracted from voxels limited to the TBSS skeleton to correspond with voxel based analyses and to reduce the influence of partial volume contamination. The ROI-segmented mean skeleton was deprojected from TBSS standard space to each participant’s native diffusion volume using the inverse of the participant’s transform to standard space to extract native values. An example of this procedure is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Tract based spatial statistics (TBSS) based ROI analysis procedure. A region of interest (ROI) template was co-registered with each individual’s diffusion skeleton for the creation of multiple anatomically defined ROIs. Data extraction was performed in native voxel space and was limited to the voxels contributing to the TBSS skeleton to minimize the confounding effect of partial volume contamination on the regional measurements.

White matter hypointensity labeling

White matter hypointensities were labeled on T1 images using procedures for whole brain labeling described in prior work (Fischl et al., 2002), extended to the labeling of white matter lesions as applied in our previous work (Salat et al., 2010). A frequency map of regional hypointensity distribution was created in TBSS space to qualitatively assess the spatial distribution of effects of MABP relative to the distribution of overt white matter lesions.

Data Analysis

Voxelwise general linear models (GLM) were performed to examine regional associations between MABP and white matter microstructure measures. Additional analyses examined the same associations in normotensive to mildly hypertensive individuals, as well as the association between MABP and white matter microstructure controlling for age. Secondary analyses examined the effects of several potentially important covariates on the associations measured in the anterior corpus callosum, including smoking, sex, education, body mass index, and total white matter lesion volume.

RESULTS

Associations between blood pressure and DTI measures: TBSS Voxel-based GLMs

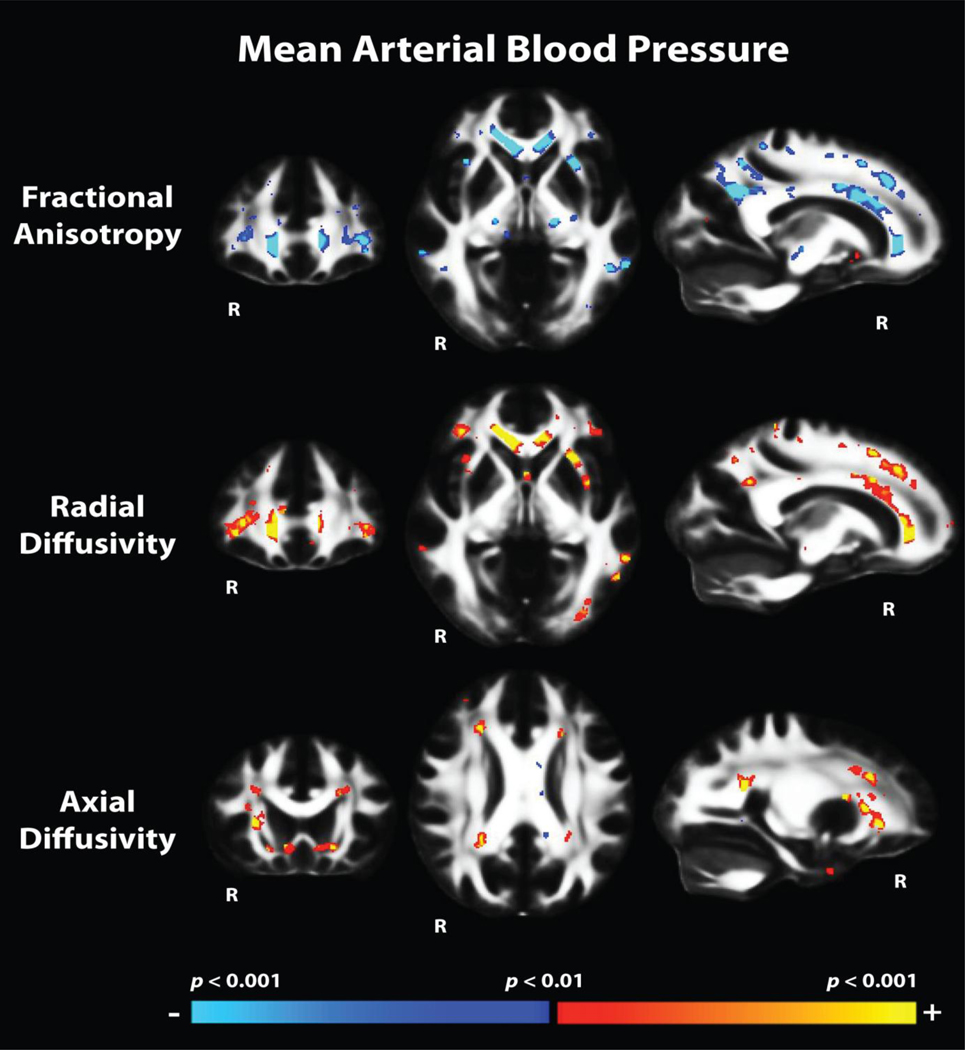

Associations were found between MABP and FA in several regions throughout the cerebral white matter with strong bilateral effects in the corpus callosum (particularly anterior regions), parietal white matter (particularly inferior and superior lateral parietal and precuneus), and superior and lateral frontal white matter (Figure 3). Regional definitions of significance clusters are presented in Table 3, with the size and minimum p value for each cluster, and a weighting score for each region that takes both cluster size and statistical significance into account. While FA and radial diffusivity had a similar spatial distribution of regional associations with MABP, axial diffusivity was associated with MABP to a lesser degree and in different regions including more posterior and periventricular white matter. The majority of regional associations remained when controlling for age, which only minimally affected the overall results.

Figure 3.

Tract-Based Spatial Statistics (TBSS) maps demonstrating regions with associations between mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) and white matter microstructural measures. The heat scale represents statistical p values as described in the figure color scale-bar. Associations were found throughout the cerebral white matter with prominent associations between MABP and white matter integrity in frontal and parietal areas for fractional anisotropy (FA) and redial diffusivity. In contrast, associations between MABP and axial diffusivity were found primarily in perventricular regions and orbitofrontal and medial temporal regions.

Table 3.

Anatomic assignment of significance clusters from the TBSS voxel-based analysis of the association between MABP and FA (Figure 3; p< 0.01; minimum cluster size 40mm3).

| Region | Size (mm3) | Minimum p value (10−x) | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal | |||

| Rh-superior temporal | 136 | 5.03 | 684.08 |

| Lh-middle temporal | 73 | 4.64 | 338.72 |

| Lh-inferior temporal | 43 | 3.51 | 150.93 |

| Rh-middle temporal | 40 | 3.58 | 143.20 |

| Parietal | |||

| Lh-inferior/superior parietal | 489 | 5.83 | 2850.87 |

| Rh-precuneus | 370 | 6.94 | 2567.80 |

| Rh-postcentral | 374 | 5.81 | 2172.94 |

| Rh-inferior parietal/supramarginal | 390 | 5.47 | 2133.30 |

| Lh-superior parietal | 158 | 5.78 | 913.24 |

| Lh-precuneus | 132 | 4.72 | 623.04 |

| Rh-precuneus | 131 | 4.09 | 535.79 |

| Lh-postcentral | 95 | 4.11 | 390.45 |

| Lh-precuneus | 66 | 3.45 | 227.70 |

| Lh-superior parietal | 65 | 3.31 | 215.15 |

| Rh-superior parietal | 57 | 3.69 | 210.33 |

| Rh-inferior parietal | 56 | 3.44 | 192.64 |

| Lh-supramarginal | 42 | 4.29 | 180.18 |

| Frontal | |||

| Lh-parsopercularis | 168 | 5.22 | 876.96 |

| Rh-parstriangularis | 174 | 4.05 | 704.70 |

| Lh-rostral middle frontal | 135 | 4.60 | 621.00 |

| Rh-superior frontal | 137 | 4.19 | 574.03 |

| Lh-superior frontal | 135 | 3.89 | 525.15 |

| Rh-precentral | 164 | 3.13 | 513.32 |

| Lh-parstriangularis | 125 | 3.99 | 498.75 |

| Lh-precentral | 88 | 5.09 | 447.92 |

| Rh-parsopercularis | 94 | 3.84 | 360.96 |

| Rh-superior frontal | 89 | 3.92 | 348.88 |

| Lh-precentral | 79 | 3.37 | 266.23 |

| Rh-caudal middle frontal | 69 | 3.27 | 225.63 |

| Rh-precentral | 57 | 3.87 | 220.59 |

| Lh-paracentral | 45 | 3.84 | 172.80 |

| Rh-precentral | 57 | 2.96 | 168.72 |

| Lh-parsopercularis | 57 | 2.91 | 165.87 |

| Rh-superior frontal | 56 | 2.77 | 155.12 |

| Rh-parsopercularis | 53 | 2.81 | 148.93 |

| Rh-rostral middle frontal | 40 | 3.13 | 125.20 |

| Occipital | |||

| Rh-lateral occipital | 82 | 4.25 | 348.50 |

| Lh-lateral occipital | 106 | 2.68 | 284.08 |

| Lh-lateral occipital | 57 | 3.93 | 224.01 |

| Lh-posterior thalamic radiation | 75 | 2.93 | 219.75 |

| Rh-lateral occipital | 41 | 3.72 | 152.52 |

| Lh-posterior thalamic radiation | 45 | 2.79 | 125.55 |

| Deep/other | |||

| Body/Genu of corpus callosum | 3295 | 6.89 | 22702.55 |

| Rh-posterior thalamic radiation | 296 | 3.92 | 1160.32 |

| Lh-anterior corona radiate | 215 | 5.39 | 1158.85 |

| Lh-external capsule | 181 | 6.13 | 1109.53 |

| Lh-Bankssts | 169 | 4.58 | 774.02 |

| Lh-posterior cingulated | 151 | 3.64 | 549.64 |

| Lh-anterior limb of internal capsule | 150 | 3.63 | 544.50 |

| Splenium of corpus callosum | 112 | 3.78 | 423.36 |

| Body of corpus callosum | 111 | 3.16 | 350.76 |

| Rh-posterior corona radiate | 77 | 4.46 | 343.42 |

| Rh-tapetum | 59 | 4.65 | 274.35 |

| Lh-cerebral peduncle | 54 | 3.79 | 204.66 |

| Lh-corticospinal tract/cerebral peduncle | 49 | 2.86 | 140.14 |

| Body of corpus callosum | 48 | 2.80 | 134.40 |

| Lh-superior corona radiate | 46 | 2.59 | 119.14 |

Weighting column calculated by multiplication of the cluster size by minimum p value in the cluster, and used as a comparative metric among regional effects.

Associations between blood pressure and DTI measures: Atlas-based ROI analysis

Table 4 presents associations between MABP and diffusion measures in anatomically defined ROIs using the JHU and Freesurfer white matter atlases. These analyses matched the voxel-based results demonstrating strong, bilateral regional associations between MABP and FA and radial diffusivity in several large portions of frontal and parietal white matter. However, the anatomical ROI analysis demonstrated several additional regions throughout the cerebrum showing associations between MABP and white matter integrity including occipital, temporal, and deep white matter.

Table 4.

Region of interest analyses using atlas-based labels.

| Region | FA | Radial Diff. | Axial Diff. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | P- value |

F | P-value | F | P- value |

|

| Frontal | ||||||

| Lh-Parstriangularis | 21.016 | .000 | 14.261 | .000 | NS | NS |

| Lh-Parsopercularis | 15.161 | .000 | 8.164 | .005 | NS | NS |

| Rh-Parstriangularis | 14.454 | .000 | 14.746 | .000 | 4.976 | .027 |

| Lh-Precentral | 12.862 | .000 | 6.062 | .015 | NS | NS |

| Rh-Parsopercularis | 11.666 | .001 | 10.981 | .001 | NS | NS |

| Lh-Caudalmiddlefrontal | 11.198 | .001 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Rh-Caudalmiddlefrontal | 10.658 | .001 | 7.694 | .006 | NS | NS |

| Rh-Precentral | 10.320 | .002 | 7.696 | .006 | NS | NS |

| Lh-Rostralmiddlefrontal | 9.414 | .003 | 8.958 | .003 | NS | NS |

| Lh-Lateralorbitofrontal | 8.171 | .005 | 7.056 | .009 | NS | NS |

| Rh-Superiorfrontal | 7.922 | .006 | 7.819 | .006 | NS | NS |

| Rh-Paracentral | 7.733 | .006 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Lh-Superiorfrontal | 7.033 | .009 | 5.113 | .025 | NS | NS |

| Rh-Rostralmiddlefrontal | 6.089 | .015 | 7.953 | .006 | 4.078 | .046 |

| Lh-Paracentral | 5.373 | .022 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Lh-Parsorbitalis | NS | NS | 5.613 | .019 | 5.411 | .022 |

| Rh-Lateralorbitofrontal | NS | NS | 7.623 | .007 | 4.036 | .047 |

| Rh-Medialorbitofrontal | NS | NS | 7.732 | .006 | 7.588 | .007 |

| Rh-Parsorbitalis | NS | NS | 5.570 | .020 | 4.020 | .047 |

| Cingulum | ||||||

| Lh-Isthmuscingulate | 8.003 | .005 | 4.902 | .029 | NS | NS |

| Lh-Posteriorcingulate | 6.149 | .014 | NS | NS | 5.313 | .023 |

| Rh-Caudalanteriorcingulate | 5.571 | .020 | 8.370 | .004 | NS | NS |

| Lh-Rostralanteriorcingulate | NS | NS | 5.107 | .026 | NS | NS |

| Rh-Rostralanteriorcingulate | NS | NS | 10.199 | .002 | 8.290 | .005 |

| Parietal | ||||||

| Rh-Inferiorparietal | 19.087 | .000 | 6.250 | .014 | NS | NS |

| Rh-Precuneus | 18.945 | .000 | 7.227 | .008 | NS | NS |

| Lh-Inferiorparietal | 17.796 | .000 | 7.306 | .008 | NS | NS |

| Lh-Superiorparietal | 17.526 | .000 | 5.762 | .018 | NS | NS |

| Lh-Precuneus | 15.077 | .000 | 5.657 | .019 | NS | NS |

| Rh-Postcentral | 15.023 | .000 | 11.964 | .001 | NS | NS |

| Rh-Supramarginal | 13.669 | .000 | 5.527 | .020 | NS | NS |

| Lh-Postcentral | 11.440 | .001 | 10.252 | .002 | NS | NS |

| Lh-Supramarginal | 10.710 | .001 | 6.705 | .011 | NS | NS |

| Rh-Superiorparietal | 9.714 | .002 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Deep/Other | ||||||

| Genu-of-corpus-callosum | 26.462 | .000 | 26.583 | .000 | NS | NS |

| Body-of-corpus-callosum | 11.542 | .001 | 7.959 | .006 | NS | NS |

| Rh-Inferior-cerebellar-peduncle | 9.219 | .003 | 4.734 | .031 | NS | NS |

| Lh-Inferior-cerebellar-peduncle | 6.261 | .014 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Fornix-column-and-body | 6.256 | .014 | 4.727 | .032 | 4.137 | .044 |

| Lh-Anterior-corona-radiata | 6.018 | .016 | 6.749 | .010 | NS | NS |

| Rh-Anterior-corona-radiata | 5.567 | .020 | 8.482 | .004 | 6.158 | .014 |

| Lh-Uncinate-fasciculus | 5.200 | .024 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Rh-Uncinate-fasciculus | 5.078 | .026 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Lh-Superior-fronto-occipital-fasciculus | 4.450 | .037 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Lh-External-capsule | 4.195 | .043 | 5.949 | .016 | NS | NS |

| Rh-External-capsule | NS | NS | 4.109 | .045 | NS | NS |

| Temporal | ||||||

| Lh-Bankssts | 18.880 | .000 | 5.848 | .017 | NS | NS |

| Lh-Middletemporal | 8.695 | .004 | 5.439 | .021 | NS | NS |

| Rh-Bankssts | 7.904 | .006 | 4.544 | .035 | NS | NS |

| Rh-Middletemporal | 6.933 | .010 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Lh-Entorhinal | NS | NS | 7.327 | .008 | 5.118 | .025 |

| Rh-Temporalpole | NS | NS | NS | NS | 5.698 | .018 |

| Rh-Entorhinal | NS | NS | NS | NS | 10.277 | .002 |

| Occipital | ||||||

| Rh-Lateraloccipital | 8.560 | .004 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Lh-Lateraloccipital | 5.410 | .022 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

Influence of health and demographic variables

To examine the influence of health and demographic parameters on the associations between MABP and white matter microstructure, gender, body mass index (BMI), education, smoking status, and total white matter hypointensity volume were entered as nuisance covariates in individual general linear models of the association between MABP and DTI measures. Use of these covariates had minimal effect on the overall statistical effects demonstrated in Figure 3 except for total white matter hypointensity volume which reduced but did not eliminate the regional associations between MABP and white matter microstructure. The influence of each of these parameters on FA within the anterior callosum is presented in Figure 4 along with the whole brain maps demonstrating the effect of including white matter hypointensities as a nuisance covariate in the model of the association between MABP and DTI measures (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Influence of health and demographic variables on the association between MABP and white matter microstructural measures. Scatterplots in the left panel demonstrate the association between mean fractional anisotropy in the anterior corpus callosum and MABP, total white matter hypointensity volume, smoking status, gender, body mass index, and education. When entered into the model as nuisance variables, only white matter hypointensity volume had an impressionable impact on the association between MABP and white matter microstructure as demonstrated in the right panel compared to the results in Figure 3.

Spatial overlap of MABP effects with white matter hypointensities (WMH)

White matter lesions are a common feature in individuals with hypertension and cerebrovascular disease and statistically controlling for white matter hypointensity volume influenced the association between MABP and DTI measures (Figure 4). In order to determine whether the associations between MABP and white matter integrity had a similar spatial distribution to white matter lesions, the spatial frequencies of white matter hypointensities were mapped to the TBSS standard space, allowing a simple qualitative co-visualization of the lesions with the MABP significance maps to determine whether the effects measured were simply within regions of high lesion frequency. Spatial frequencies of WMH can be seen in Figure 5. WMH frequency maps were thresholded to demonstrate regions where ≥ 30 participants demonstrated labeling. These maps demonstrate that, although there was some overlap between regions with white matter lesions and the regions impacted by MABP, many of the regional associations were outside of this zone of overlap. A portion of the significance regions directly bordered white matter lesions; however, other clusters were remote to the common periventricular location of white matter damage. This finding plus the finding that associations remain between MABP and DTI measures when controlling for hypointensity volume support the unique association between blood pressure and microstructural alterations.

Figure 5.

Spatial overlap between white matter signal abnormalities (WMSA) and regions showing associations between mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) and diffusion metrics. Although spatial overlap was apparent, the majority of regions showing associations between MABP and fractional anisotropy (FA) were located outside of WMSA in regions bordering white matter lesions as well as more peripheral white matter.

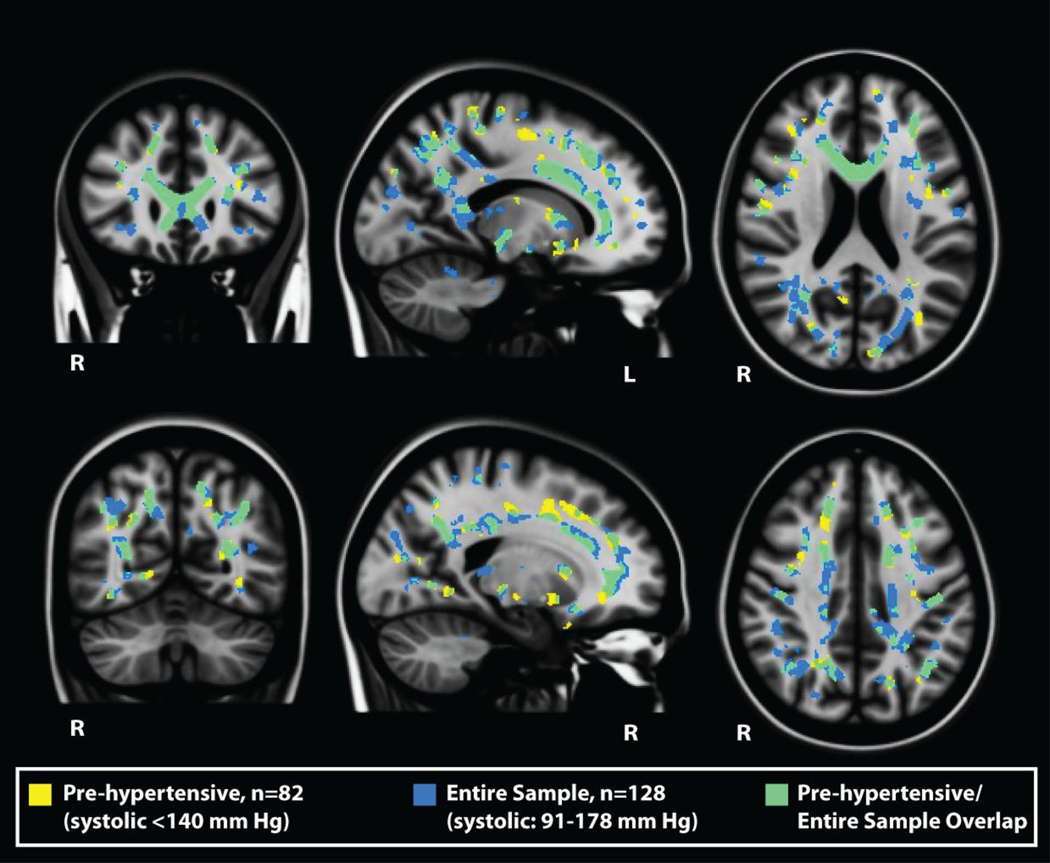

Associations in normotensive and controlled/pre-hypertensive individuals

We performed the same analyses as described above while limiting the sample to those participants who were normotensive and controlled/pre-hypertensive only. Figure 6 demonstrates the spatial overlap of the analyses performed in these two samples (p < 0.05). There was strong overlap in the significance maps of the full sample and the truncated MABP sample. Significance clusters in the larger sample were expanded relative to the truncated sample, and extended more posteriorly than the effects seen in the truncated sample. Additionally, of the 37 identified clusters for the full sample analysis, all cluster remained significant when examining the association between MABP and FA for each cluster in the sample limited to individuals with a systolic blood pressure of > 140. A minimal set of regions showed an effect in the MABP restricted range that was not apparent in the full sample.

Figure 6.

The association between MABP and FA in a sample limited to normotensive and controlled/mildly hypertensive individuals. Regions showing significance in low risk individuals (yellow/green) were similar to analyses including the entire sample (blue/green), demonstrating that the effects observed were not primarily driven by individuals in the extreme ranges of blood pressure. Thus, blood pressure may exert an influence on neural tissue within ranges considered within normal variation.

Effect of medication on MABP associations

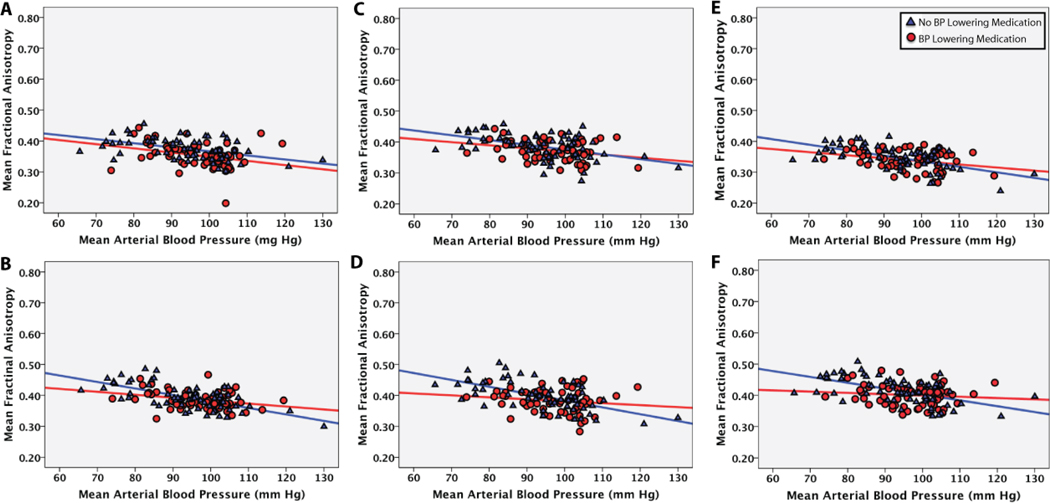

Figure 7 presents a transparent representation of the brain to demonstrate the location of major clusters from the voxel based analyses showing significant associations between MABP and FA (p < 0.01; min cluster size of 60mm3) as well as the raw data from selected clusters with the sample differentially represented based on medication usage. This representation highlights the potential vulnerability of frontal and parietal white matter to elevated blood pressure. Additionally, as demonstrated in the scatterplots, individuals on medication had similar slopes compared to individuals that were not on medication in some regions, however, there were significant MABP by medication status interactions in other regions, with some effects suggesting a reduced association in individuals on blood pressure medication compared to those that were not. A total of 37 clusters showing significant effects of MABP on FA were examined and approximately 30% of these clusters demonstrated a significant interaction for medication (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Selected regional associations between white matter measures and MABP. 6.1 Regional cluster showing greatest statistical associations between MABP and fractional anisotropy (FA) are displayed in a translucent representation of the brain. Associations were found through widespread regions of the cerebral white matter with prominent effects in frontal and parietal white matter. 6.2. Selected regional scatterplots showing the association between MABP and FA. The sample is divided based on medication useage with medicated individuals represented by red circles, and non-medicated individuals represented by blue triangles. Regions: A. left precentral white matter; B. left lateral parietal white matter; C. left precuneus white matter; D. right lateral parietal white matter; E. right postcentral white matter.

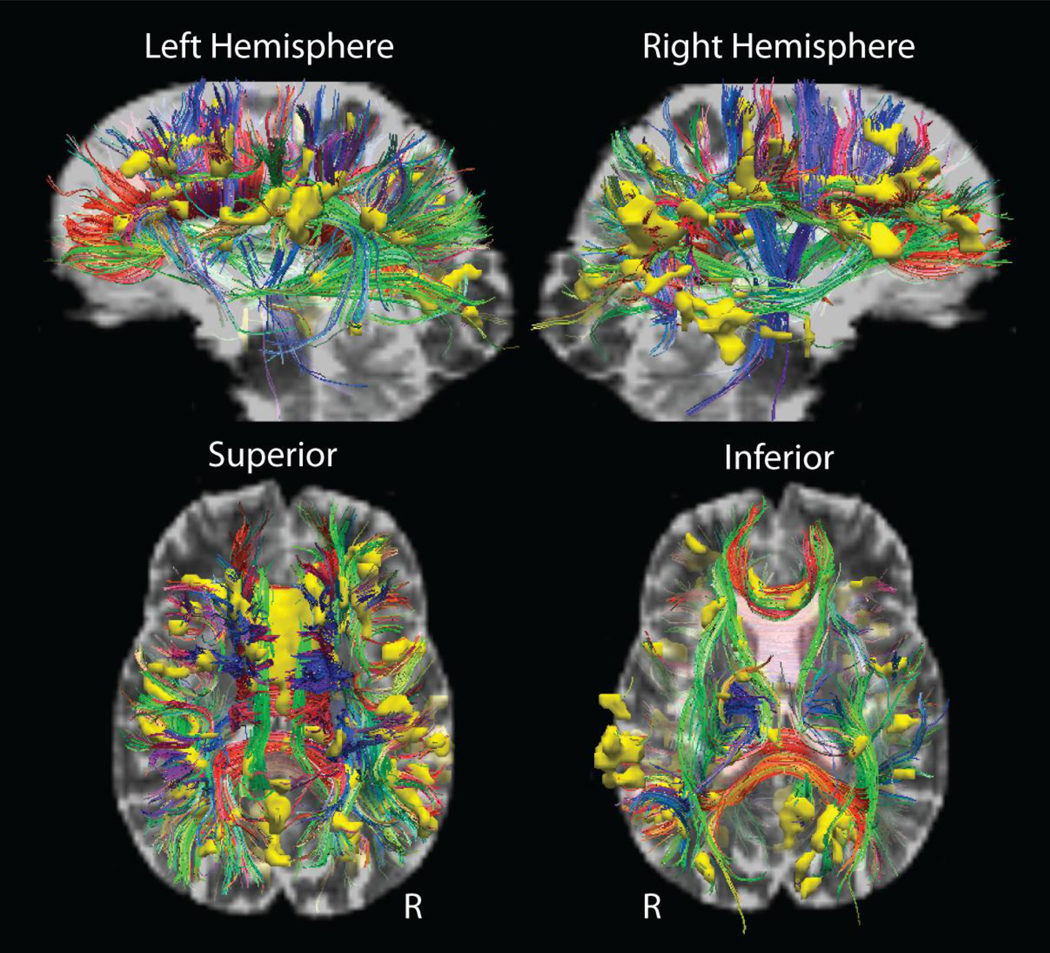

Fiber anatomy of regions associated with MABP

To determine the white matter fascicles intersecting regions demonstrating an association between MABP and FA, we utilized significance clusters from the TBSS based maps as streamline tractography seeds in a representative healthy brain. Figure 8 is the result of this modeling and demonstrates fibers intersecting regions showing significant associations including the corona radiata, the pyramidal tracts, the cingulum, and the optic radiations. This representation highlights the wide-spread complex fiber architecture that may be impacted by vascular health, as well as the relative sparing of temporal lobe fiber integrity.

Figure 8.

Diffusion tractography qualitatively demonstrating white matter fascicles potentially affected by blood pressure. Regions of demonstrating a statistically significant association between MABP and FA were clustered and entered into streamline tractography procedures to qualitatively demonstrate the fiber populations that intersected with regions showing an association between MABP and FA. This image demonstrates the potential widespread effects of blood pressure on cerebral health, however it is also of note that fibers within the temporal lobe may be relatively spared compared to fibers in frontal and parietal cortices.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated regional associations between inter-individual variation in MABP and diffusion metrics of white matter integrity throughout the cerebral white matter in a large sample of generally healthy older adults. Effects were prominent in frontal and parietal white matter, were independent of age, remained after controlling for white matter lesions, and were apparent when the sample was limited to individuals who were either normotensive or controlled and/or pre-hypertensive. It is of note that, although much of the effect was apparent in individuals within the mild risk range, the regional distribution of effects of MABP on DTI measures was expanded with the inclusion of individuals in the more severe range. These results are significant on two major levels. First, they demonstrate that vascular health may have a substantial impact on neural health, even in individuals outside of the hypertensive range, emphasizing the importance of considering measures like MABP more generally in studies of cognitive and neural aging. Second, these data may provide essential information about the optimal clinical management of blood pressure with regard to neural health in older adults. Few prior studies have explored the quantitative association between blood pressure and white matter integrity in a normative population (Kennedy and Raz, 2009b; Leritz et al., 2010a). Additionally, recent work demonstrated specific regional patterns by which blood pressure may affect white matter to contribute to geriatric depression (Hoptman et al., 2009). The current data are in concordance with these prior studies demonstrating that systemic measures of vascular function are associated with the integrity of anterior white matter. We extend these results to demonstrate the full spatial patterns of associations between blood pressure and white matter integrity measured by DTI, and the spatial associations relative to the more overt periventricular white matter lesions typically apparent in high risk and disease populations. Similarly, controlling for total white matter lesion volume reduced the effects measured, yet regional effects remained, for example, in the anterior corpus callosum. We note, however, that white matter lesions were measured as hypointensities from T1 weighted images and therefore may not account for the full spatial distribution of white matter lesions in this sample. Taken together, these studies express the importance of continued work to determine the unique mechanisms by which blood pressure variation may influence neural tissue degradation.

Our study found associations between MABP and the axial as well as the radial components of diffusivity in the current study. Axial diffusivity represents diffusion along the primary directional vector, and has been suggested to be sensitive to axonal disruption (Budde et al., 2009). This metric was associated with MABP to a lesser degree than FA, and primarily showed associations in periventricular, orbitofrontal, and medial temporal regions. In contrast, radial diffusivity represents diffusion in the non-primary directional vectors, and has been suggested to be altered more selectively with damage to myelin (Sun et al., 2006). Associations between MABP and radial diffusivity had a similar spatial pattern to the regions showing associations between MABP and FA with additional results in orbitofrontal regions. These findings may suggest that vascular health influences white matter microstructure through multiple pathologic mechanisms. For example, damage to the myelin could be due to ischemic perturbations, while fibers may only be affected with more substantial pathologies that occur with greater vascular risk. However, limitations of the interpretation of results from diffusion imaging have been noted (Wheeler-Kingshott and Cercignani, 2009). Additionally, examination of the effects of MABP on the distinct diffusivities suggests some differential sensitivity based on initial anatomy, with axial diffusivity potentially being more sensitive to changes in regions with low native FA. It is thus unclear what mechanisms may contribute to associations between MABP and DTI-based white matter integrity at this time.

MABP was related to diffusion measures in regions that bordered on the well described periventricular white matter lesions that have been found to be related hypertension. Associations were also found in more peripheral regions of white matter, outside of common locations of white matter damage. Additionally, associations between MABP and DTI measures remained when controlling for white matter hypointensity volume. The lack of a bimodal distribution of white matter values in our selected regions suggests that MABP influences white matter in a manner that is distinct to a more large-scale event such as a micro hemorrhage, stroke or other lesion. These findings suggest that a portion of the associations found in the current work represent a pre-lesional state of tissue bordering on lesion locations that will potentially expand with continued changes in health status and that these regional effects may differ from effects in areas remote to the periventricular zone that are much less likely to become overtly lesioned. Such effects have been discussed in prior work with regard to lesions form multiple sclerosis (Werring et al., 2000). Ongoing work will examine in greater detail the relationship between the manifestation of white matter lesions and the health of white matter outside of lesion locations as well as the pathologic heterogeneity of white matter lesions in older adults.

The present data demonstrate a reduction in white matter integrity with increasing blood pressure, regardless of overt hypertension. It is possible that increased blood pressure influences white matter regionally through the increased likelihood of local ischemia (Pantoni and Garcia, 1997), and that although one may not be in the range of high risk for a cerebrovascular event, increased blood pressure can still have this more subtle influence on neural tissue. Effects were found in regions intersecting several major fiber fascicles including the several regions along the corona radiata, the pyramidal tracts, the cingulum, and the optic radiations with a relative sparing of temporal lobe fibers (Figure 8). Similar systems have been suggested to be most vulnerable to the effects of aging in contrast to the more limbic effects of Alzheimer’s disease, and these findings lend greater support to the idea that vascular health is a major component of general neural aging. These data demonstrate the potentially broad, yet selective neural implications of elevated blood pressure on brain structure, and the neurophysiologic and cognitive consequences of elevated blood pressure in the low-risk population are yet to be elucidated.

The current data are limited and must be interpreted with caution. The cohort examined was not a normative population. The majority of participants had a first degree relative with dementia, and a substantial portion of the cohort was comprised of African Americans, a population known to be at increased risk for cerebrovascular disease. It is therefore possible that, blood pressure may have an amplified effect in this population, regardless of the fact that individuals are normotensive. If this were true, this finding would be of great interest in that the sample provides a unique population to uncover effects that may have been missed in prior analyses due to the subtle but significant impact on white matter structure. Additionally, although this was partially an ‘at risk’ population, the sample was recruited through advertisement and was comprised of a majority of individuals from the Boston metropolitan area who may differ in their blood pressure and MMSE scores compared to similar cohorts. The generalization of such results to other studies can therefore not be assumed. A portion of the effects measured were replicated across two independent samples examined with similar demographic profiles, and we note that our recent data demonstrates associations between MABP and DTI-based white matter measures in a more general community sample of older adults. Additionally, medication was determined not to have a major influence on specific regional associations in this work, however, a portion of the effects showed statistical interactions with those on medication showing less of an association than those that were not taking medication. This trend could be due to the fact that individuals on medication had MABP values that were less reflective of their lifetime exposure compared to those that were not. Alternatively and potentially more interesting, it is possible that blood pressure medication has a therapeutic influence on white matter damage, therefore reducing the association between MABP and tissue structure. The influence of medication and pre-medication blood pressure will therefore need to be further examined in a larger sample of participants. It is important to note that the effects described here are only associational and cross-sectional. It is therefore not possible to determine if there is a causal link between elevated blood pressure and white matter damage. Ongoing work is examining how baseline MABP predicts future changes in white matter integrity, and these analyses should provide valuable information in this regard.

In summary, these data demonstrate the association between blood pressure, a measure of systemic vascular health, and diffusion metrics of white matter integrity. Associations were independent of age and medication status, were replicable across two independent samples, and were apparent when limiting the sample to individuals with only mildly elevated blood pressure. These findings suggest that dysregulation of blood pressure may have an important impact on neural integrity in older adults, even when in the normal range with regard to cerebrovascular risk. Future work will examine the clinical implications of these findings.

Blood pressure is associated with white matter microstructure in generally healthy older adults

Associations are apparent in white matter well outside of lesioned tissue

Associations are apparent in even very low risk individuals

Variation in vascular physiology contributes to age-associated white matter degeneration

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Nursing Research (R01NR010827), National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (K23NS062148 and ARRA funds K23NS062148S1), grants from the National Institute on Aging (P60AG08812 and K01AG24898), and by Medical Research Service VA Merit Review Awards to William Milberg and Regina McGlinchey. The authors would like to thank Marge Ahlquist for her assistance with blood pressure collection on all participants and Juli Dolzhenko for assistance in preparation of this manuscript. We also thank Ruopeng Wang, Van J. Wedeen, TrackVis.org, Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital for the development of TrackVis software used for tractography procedures.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Andersson JLR, Jenkinson M, Smith S. Non-linear optimisation. 2007a FMRIB technical report TR07JA1 from www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/analysis/techrep.

- Andersson JLR, Jenkinson M, Smith S. 2007b Non-linear registration, aka Spatial normalisation FMRIB technical report TR07JA2 from www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/analysis/techrep.

- Barrick TR, Charlton RA, Clark CA, Markus HS. White matter structural decline in normal ageing: a prospective longitudinal study using tract-based spatial statistics. Neuroimage. 2010;51:565–577. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basser PJ, Mattiello J, LeBihan D. Estimation of the effective self-diffusion tensor from the NMR spin echo. J Magn Reson B. 1994;103:247–254. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1994.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastin ME, Clayden JD, Pattie A, Gerrish IF, Wardlaw JM, Deary IJ. Diffusion tensor and magnetization transfer MRI measurements of periventricular white matter hyperintensities in old age. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti B, Charil A, Rovaris M, Judica E, Valsasina P, Sormani MP, Filippi M. Influence of aging on brain gray and white matter changes assessed by conventional, MT, and DT MRI. Neurology. 2006;66:535–539. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000198510.73363.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnstedt M, Fox PJ, Kohatsu ND. Correlates of Mini-Mental Status Examination scores among elderly demented patients: the influence of race-ethnicity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:1381–1387. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breteler MM, van Swieten JC, Bots ML, Grobbee DE, Claus JJ, van den Hout JH, van Harskamp F, Tanghe HL, de Jong PT, van Gijn J, et al. Cerebral white matter lesions, vascular risk factors, and cognitive function in a population-based study: the Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 1994;44:1246–1252. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.7.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde MD, Xie M, Cross AH, Song SK. Axial diffusivity is the primary correlate of axonal injury in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis spinal cord: a quantitative pixelwise analysis. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2805–2813. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4605-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. Jama. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Agostino RB, Wolf PA, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Stroke risk profile: adjustment for antihypertensive medication. The Framingham Study. Stroke. 1994;25:40–43. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Laat KF, van Norden AG, Gons RA, van Oudheusden LJ, van Uden IW, Norris DG, Zwiers MP, de Leeuw FE. Diffusion tensor imaging and gait in elderly persons with cerebral small vessel disease. Stroke. 2011;42:373–379. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.596502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCarli C, Murphy DG, Tranh M, Grady CL, Haxby JV, Gillette JA, Salerno JA, Gonzales-Aviles A, Horwitz B, Rapoport SI, et al. The effect of white matter hyperintensity volume on brain structure, cognitive performance, and cerebral metabolism of glucose in 51 healthy adults. Neurology. 1995;45:2077–2084. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.11.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, Buckner RL, Dale AM, Maguire RP, Hyman BT, Albert MS, Killiany RJ. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31:968–980. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C, van der Kouwe A, Killiany R, Kennedy D, Klaveness S, Montillo A, Makris N, Rosen B, Dale AM. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33:341–355. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuny LA, Briggs M, Newcombe F, Ratcliff G, Thomas C. Measuring the duration of post traumatic amnesia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1980;43:377–379. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.43.5.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein IB, Bartzokis G, Hance DB, Shapiro D. Relationship between blood pressure and subcortical lesions in healthy elderly people. Stroke. 1998;29:765–772. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.4.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gons RA, de Laat KF, van Norden AG, van Oudheusden LJ, van Uden IW, Norris DG, Zwiers MP, de Leeuw FE. Hypertension and cerebral diffusion tensor imaging in small vessel disease. Stroke. 2010;41:2801–2806. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.597237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve DN, Fischl B. Accurate and robust brain image alignment using boundary-based registration. Neuroimage. 2009;48:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannesdottir K, Nitkunan A, Charlton RA, Barrick TR, MacGregor GA, Markus HS. Cognitive impairment and white matter damage in hypertension: a pilot study. Acta Neurol Scand. 2009;119:261–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Sengupta M, Velkoff VA, DeBarros KA. Current Population Reports. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health, National Institutes on Aging; 2005. 65+ in the United States: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hoptman MJ, Gunning-Dixon FM, Murphy CF, Ardekani BA, Hrabe J, Lim KO, Etwaroo GR, Kanellopoulos D, Alexopoulos GS. Blood pressure and white matter integrity in geriatric depression. J Affect Disord. 2009;115:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeerakathil T, Wolf PA, Beiser A, Massaro J, Seshadri S, D'Agostino RB, DeCarli C. Stroke risk profile predicts white matter hyperintensity volume: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 2004;35:1857–1861. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000135226.53499.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DK, Horsfield MA, Simmons A. Optimal strategies for measuring diffusion in anisotropic systems by magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:515–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy KM, Raz N. Aging white matter and cognition: differential effects of regional variations in diffusion properties on memory, executive functions, and speed. Neuropsychologia. 2009a;47:916–927. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy KM, Raz N. Pattern of normal age-related regional differences in white matter microstructure is modified by vascular risk. Brain Res. 2009b;1297:41–56. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DY, Fletcher E, Martinez O, Ortega M, Zozulya N, Kim J, Tran J, Buonocore M, Carmichael O, DeCarli C. Regional pattern of white matter microstructural changes in normal aging, MCI, and AD. Neurology. 2009;73:1722–1728. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c33afb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leritz EC, Salat DH, Milberg WP, Williams VJ, Chapman CE, Grande LJ, Rudolph JL, Schnyer DM, Barber CE, Lipsitz LA, McGlinchey RE. Variation in blood pressure is associated with white matter microstructure but not cognition in African Americans. Neuropsychology. 2010a;24:199–208. doi: 10.1037/a0018108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leritz EC, Salat DH, Williams VJ, Schnyer DM, Rudolph JL, Lipsitz L, Fischl B, McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP. Thickness of the human cerebral cortex is associated with metrics of cerebrovascular health in a normative sample of community dwelling older adults. Neuroimage. 2010b doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longstreth WT, Jr, Manolio TA, Arnold A, Burke GL, Bryan N, Jungreis CA, Enright PL, O'Leary D, Fried L. Clinical correlates of white matter findings on cranial magnetic resonance imaging of 3301 elderly people. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke. 1996;27:1274–1282. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.8.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolio TA, Olson J, Longstreth WT. Hypertension and cognitive function: pathophysiologic effects of hypertension on the brain. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2003;5:255–261. doi: 10.1007/s11906-003-0029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan M. Imaging small vessel disease: lesion topography, networks, and cognitive deficits investigated with MRI. Stroke. 2010;41:S154–S158. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan M, Jones DK, Summers PE, Morris RG, Williams SC, Markus HS. Evidence for cortical “disconnection” as a mechanism of age-related cognitive decline. Neurology. 2001;57:632–638. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.4.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel B, Markus HS. Magnetic resonance imaging in cerebral small vessel disease and its use as a surrogate disease marker. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:47–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV, Hedehus M, Lim KO, Adalsteinsson E, Moseley M. Age-related decline in brain white matter anisotropy measured with spatially corrected echo-planar diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:259–268. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200008)44:2<259::aid-mrm13>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierpaoli C, Alger JR, Righini A, Mattiello J, Dickerson R, Des Pres D, Barnett A, Di Chiro G. High temporal resolution diffusion MRI of global cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:892–905. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierpaoli C, Righini A, Linfante I, Tao-Cheng JH, Alger JR, Di Chiro G. Histopathologic correlates of abnormal water diffusion in cerebral ischemia: diffusion-weighted MR imaging and light and electron microscopic study. Radiology. 1993;189:439–448. doi: 10.1148/radiology.189.2.8210373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Lindenberger U, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Head D, Williamson A, Dahle C, Gerstorf D, Acker JD. Regional brain changes in aging healthy adults: general trends, individual differences and modifiers. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1676–1689. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Rodrigue KM, Acker JD. Hypertension and the brain: vulnerability of the prefrontal regions and executive functions. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:1169–1180. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.6.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese TG, Heid O, Weisskoff RM, Wedeen VJ. Reduction of eddy-current-induced distortion in diffusion MRI using a twice-refocused spin echo. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:177–182. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueckert D, Sonoda LI, Hayes C, Hill DL, Leach MO, Hawkes DJ. Nonrigid registration using free-form deformations: application to breast MR images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1999;18:712–721. doi: 10.1109/42.796284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salat DH, Greve DN, Pacheco JL, Quinn BT, Helmer KG, Buckner RL, Fischl B. Regional white matter volume differences in nondemented aging and Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage. 2009;44:1247–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salat DH, Tuch DS, Greve DN, van der Kouwe AJ, Hevelone ND, Zaleta AK, Rosen BR, Fischl B, Corkin S, Rosas HD, Dale AM. Age-related alterations in white matter microstructure measured by diffusion tensor imaging. Neurobiol Aging. 2005a;26:1215–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salat DH, Tuch DS, Hevelone ND, Fischl B, Corkin S, Rosas HD, Dale AM. Age-related changes in prefrontal white matter measured by diffusion tensor imaging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005b;1064:37–49. doi: 10.1196/annals.1340.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salat DH, Tuch DS, van der Kouwe AJ, Greve DN, Pappu V, Lee SY, Hevelone ND, Zaleta AK, Growdon JH, Corkin S, Fischl B, Rosas HD. White matter pathology isolates the hippocampal formation in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:244–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Beiser A, Elias MF, Au R, Kase CS, D'Agostino RB, DeCarli C. Stroke risk profile, brain volume, and cognitive function: the Framingham Offspring Study. Neurology. 2004;63:1591–1599. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000142968.22691.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp. 2002;17:143–155. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols TE, Mackay CE, Watkins KE, Ciccarelli O, Cader MZ, Matthews PM, Behrens TE. Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1487–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, De Stefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23 Suppl 1:S208–S219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Adalsteinsson E, Hedehus M, Ju C, Moseley M, Lim KO, Pfefferbaum A. Equivalent disruption of regional white matter microstructure in ageing healthy men and women. Neuroreport. 2001;12:99–104. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200101220-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun SW, Liang HF, Trinkaus K, Cross AH, Armstrong RC, Song SK. Noninvasive detection of cuprizone induced axonal damage and demyelination in the mouse corpus callosum. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:302–308. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan GE, DeCarli C, Miller BL, Reed T, Wolf PA, Jack LM, Carmelli D. Association of midlife blood pressure to late-life cognitive decline and brain morphology. Neurology. 1998;51:986–993. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.4.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virta A, Barnett A, Pierpaoli C. Visualizing and characterizing white matter fiber structure and architecture in the human pyramidal tract using diffusion tensor MRI. Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;17:1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(99)00048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werring DJ, Brassat D, Droogan AG, Clark CA, Symms MR, Barker GJ, MacManus DG, Thompson AJ, Miller DH. The pathogenesis of lesions and normal-appearing white matter changes in multiple sclerosis: a serial diffusion MRI study. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 8):1667–1676. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.8.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Cercignani M. About “axial” and “radial” diffusivities. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:1255–1260. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshita M, Fletcher E, Harvey D, Ortega M, Martinez O, Mungas DM, Reed BR, DeCarli CS. Extent and distribution of white matter hyperintensities in normal aging, MCI, and AD. Neurology. 2006;67:2192–2198. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000249119.95747.1f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]