Abstract

This qualitative descriptive study explored grand multiparous women’s perceptions of the evolving changes in birthing, nursing care, and technology. A purposive sample of grand multiparous women (N = 13) from rural, eastern Washington State were interviewed as they shared their 105 birth stories. Eight themes were identified: (1) providing welcome care, (2) offering choices, (3) following birth plans, (4) establishing trust and rapport, (5) being an advocate, (6) providing reassurance and support, (7) relying on electronic fetal monitors and assessments versus nursing presence, and (8) having epidurals coupled with loss of bodily cues. Results from this study may be used to educate women, intrapartum nurses, and childbirth educators on nursing care and on the evolving use of technology to better manage intrapartum care in hospitals. The results can also add to the extant knowledge of childbirth nursing practices.

Keywords: childbirth, nurse–patient relationship, obstetric care, qualitative research, technology

Childbirth can be a momentous and pivotal life experience for women. Life has changed as they had known it when they take on the new and vital role of being a “mother.” Grand multiparous women are mothers who have experienced—on average—five or more births (Varney, Kriebs, & Gegor, 2004). With their numerous birth experiences in hospitals over many years, grand multiparous women may have gained valuable birthing expertise and insight. Their birthing experiences throughout the years can provide rich descriptions and perceptions of the evolving integration of technology with professional labor support by intrapartum nurses in hospitals.

Mothers often enjoy sharing their birth stories. Indeed, while conducting the Listening to Mothers II survey in the United States, researchers found that mothers were “exceptionally engaged,” eager to share their birth stories, and willing to spend more time during the survey interviews than is typically expected (Declercq, Sakala, Corry, & Applebaum, 2006, p. 2). Mothers have the ability to recall sentinel experiences of childbirth many years later, with incredible accuracy, as they retell their stories (Simkin, 2002).

This qualitative study explored grand multiparous women’s perceptions and descriptions of the evolving change in birthing practices, the nursing care (professional labor support), and the use of technology in the hospital environment. The study’s interviews offered a rare opportunity for grand multiparous women to share their individual birthing experiences that occurred over many years, during their childbearing years.

Grand multiparous women, who have experienced five or more birthing experiences, may have given birth over a period of 2–4 decades, which reflect the ongoing changes of the hospital birthing environment. Mothers who have given birth to five or more children may have strong intentions of preserving the integrity of the uterus. Thus, they develop and commit to birthing practices that favor vaginal births (Smart, 2004). In addition, grand multiparous women can share what they perceive as changes in institutional, nursing, and obstetrical practices over many years. Furthermore, they can offer insight into the meanings attributed to the use of technology and their relationship with nurses during childbirth.

PURPOSE AND SIGNIFICANCE

The purpose of this qualitative descriptive study was to explore grand multiparous women’s perceptions and descriptions of birthing, nursing care, and the interplay of technology during childbirth in hospitals. Their perceptions and descriptions can uncover the essence of women’s birth experiences, their relationship with intrapartum nurses, and the use of technology during birth. The findings from this study may be used to educate women, intrapartum nurses, and childbirth educators on nursing care and the influence of technology on laboring women to better manage intrapartum care in hospitals. The study’s findings can also add to the extant knowledge of childbirth practices.

Mothers have the ability to recall sentinel experiences of childbirth many years later, with incredible accuracy, as they retell their stories.

LITERATURE SEARCH

Parity

A preliminary literature search via the Cochrane and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) databases using the terms “grand multip,” “grand mulitipara,” “grand multiparity,” and “grand multiparous” revealed 12 quantitative studies. Ten of the studies were conducted outside of the United States: three in Israel; two in Finland; and one each in Jordan, Belgium, France, Nigeria, and the United Arab Emirates. These quantitative studies of mothers who gave birth to five or more babies focused on labor outcomes, birth weights, and maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. When adding the terms “labor support” and “labor technology” to our literature search on grand multiparous women, no additional literature was retrieved. Thus, there is an inference that a gap exists in the literature on interviewing grand multiparous women and their descriptions of birth, the essence of the care by nurses, and the interplay of technology during childbirth.

An additional search for the definitions of “grand multiparous” and “parity” was conducted. Characteristically, grand multiparous women are described as mothers who have given birth to more than five to seven babies (Varney et al., 2004; Venes, 2009). Parity is often described as the number of pregnancies that result in a live birth (Varney et al., 2004).

Labor Support

Labor support describes the care that is provided to women during childbirth (Adams & Bianchi, 2008; Hodnett, Gates, Hofmeyr, & Sakala, 2007; Payant, Davies, Graham, Peterson, & Clinch, 2008; Sauls, 2006; Simkin, 2002). Labor support is essentially “mothering the mother” and has been described as the supportive care given by others (e.g., doulas, husbands or partners, and nurses) to pregnant women during the birthing process. One-to-one labor support, in which one person provides continuous care to one mother during labor, can reduce laboring women’s anxiety and decrease stress hormones that have a vasoconstrictive effect leading to decreased uterine blood flow (Romano & Lothian, 2008). Labor support can be provided by numerous members of the health-care team as well as the woman’s personal support system.

Professional Labor Support

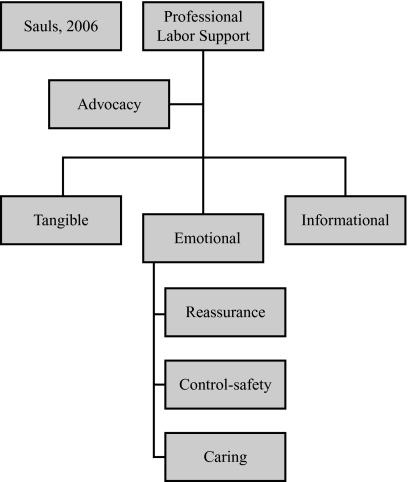

Labor support given by nurses encompasses an array of interventions that include advocacy, social support, emotional support, instructional care, partner support, physical comfort measures, safety, and technical care (Adams & Bianchi, 2008; Hodnett et al., 2007; Sauls, 2006). For this study, the term “professional labor support” was used to refer to nurses who give labor support. Sauls (2000) described professional labor support as the “intentional human interaction between intrapartum nurses and the laboring client that assists her to cope in a positive manner during the process of giving birth” (p. 124). Sauls (2006) identified the following six dimensions to describe professional labor support from the perspective of intrapartum nurses: (1) advocacy; (2) tangible support; (3) emotional support that provides reassurance; (4) emotional support that promotes control, security, and comfort; (5) emotional support that requires the nurse’s caring behavior; and (6) informational support (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Professional Labor Support

Note. The six dimensions of professional labor support, based on Sauls, D. J. (2006). Dimensions of professional labor support for intrapartum practice Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 38(1), 36–41.

Technology

Today, many mothers in the United States expect the hospital birth experience to be procedure-intensive. Procedures such as the use of synthetic pitocin inductions, continuous electronic fetal monitoring, intravenous fluids, and epidurals are commonly administered to women giving birth in U.S. hospitals (Declercq et al., 2006). Declercq and colleagues confirmed that a high-tech birth environment is customary in U.S. hospitals, which demonstrate a 34% rate of induction, a 94% rate in the use of electronic fetal monitoring, and a 76% rate in the use of epidural analgesia. Women often desire, or at least accept, these procedures; however, negative consequences are associated with the abundant use of technological procedures. Although technology can enhance labor outcomes, the demands of technology can supersede the supportive care given by nurses. Zwelling (2008) suggested using a balanced combination of high-technology and high-touch care practices that include allowing labor to begin on its own, allowing freedom of movement during labor, and providing continuous labor support.

Today, nursing care during the birthing process encompasses various interventions, including interpreting data from the high-technology environment often seen in U.S. hospitals. In the United States, as the implementation of technology during labor has increased, nurses’ emotional and physical comfort measures provided for laboring women have decreased (Declercq et al., 2006). Therefore, the intrapartum nurse’s role presents a dichotomy between performing an increasingly high-technological practice of care and providing face-to-face comfort and support for laboring women. Historically, a crucial element in the birthing experience for women has been the relationship formed with the professional nurse; unfortunately, technology can hamper this relationship. Numerous experts in the health-care disciplines perceive that technology is a dehumanizing aspect of the natural birth experience (Hodnett et al., 2007; Romano & Lothian, 2008; Sauls, 2006).

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS

This study used a qualitative descriptive approach, which is a fundamental, eclectic method of inquiry (Sandelowski, 2000). Grand multiparous women were interviewed to elicit their perceptions of the birthing process, the role of professional labor support (nursing care) in hospitals, and the use of childbirth-related technology in hospitals.

Research Questions

The primary research question in our study was, “What are grand multiparous women’s perceptions and descriptions of nursing care during childbirth?” The study’s secondary research question was, “What are grand multiparous women’s perceptions of nurses’ use of technology during childbirth?”

Participants and Setting

A target sample of 13 grand multiparous women was obtained, using a purposive convenience sampling method. Sampling was discontinued when no new themes emerged from the data and data saturation occurred. The participants were recruited from our professional and personal contacts; in addition, we employed a snowball-recruitment method (in which women referred other women).

Participants were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: English-speaking women who had given birth to five or more babies, had given birth in a hospital to at least four babies, and had not given birth in the last 12 months. Although all of the 13 participants currently resided in rural, eastern Washington State, they had given birth in hospitals located in other U.S. states and in other countries (see Table 1). Each participant averaged 8.08 births, which represented 105 birthing experiences among the study’s sample. The participants exhibited an epidural rate of 23% and a cesarean surgery rate of 6.7%.

TABLE 1. Grand Multiparous Women’s Demographics (N = 13).

| Age (in Years) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 47.85 | |

| Range | 36–63 | |

| Educational Level | ||

| High school | 8 | |

| Postsecondary | 4 | |

| Graduate degree | 1 | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 12 | |

| Divorced | 1 | |

| Birth Place, Number of Births, and Birth Location | ||

| Country/State | Number of Births (Total: 105) | Location |

| Alberta, Canada | 1 | Community hospital |

| Vladikavkaz, Russia | 9 | Urban hospital |

| United States (95) | ||

| Alaska | 1 | Home birth |

| Arizona (5) | 3 | Urban hospital |

| 2 | Community hospital | |

| California (6) | 5 | Community hospital |

| 1 | Urban hospital | |

| Idaho | 2 | Rural hospital |

| Illinois | 1 | Military hospital |

| Iowa | 4 | Community hospital |

| Montana | 1 | Rural hospital |

| New Mexico | 5 | Community hospital |

| Utah | 5 | Community hospital |

| Washington (65) | 7 | Home birth |

| 18 | Rural hospital | |

| 22 | Community hospital | |

| 16 | Urban hospital | |

| 2 | Military hospital | |

Procedures

Washington State University’s institutional review board granted approval for our study. All participants volunteered and offered their consent. They agreed to be interviewed for 60–90 minutes in their home or at a mutually convenient location (e.g., school, church, or hospital). The participants were given the opportunity to self-select a pseudonym for this study or to use their given first name. The initial interview question was, “I am interested in the childbirth experiences of grand multiparous women with nurses and the interplay of technology during childbirth. Will you tell me about your experiences?” This open-ended, initial question was augmented with probes, as needed, regarding the women’s birthing experiences, childbirth history, nursing care during their birth experiences, and the use of technology during their birth experiences. The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim for analysis.

Data Analysis

We conducted a thematic analysis on the audiotapes, transcriptions, and field notes. Field notes and demographic information provided an additional source of data for analysis. Themes were identified and categorized between the two research questions of our study: (1) “What are grand multiparous women’s perceptions and descriptions of nursing care during childbirth?” and (2) “What are grand multiparous women’s perceptions of nurses’ use of technology during childbirth?”

To confirm our study’s trustworthiness, a team of nurse researchers who were familiar with the study’s content (perinatal) and/or design (qualitative descriptive) reviewed the study’s data. To establish our study’s validity, we chose the following evaluation criteria developed by Whittemore, Chase, and Mandle (2001): the primary criteria of credibility, authenticity, criticality, and integrity. These criteria are the standards that are upheld and represent the truthfulness of a study’s findings. The secondary criteria of explicitness, vividness, creativity, thoroughness, congruence, and sensitivity provided supplementary guiding principles to the primary criteria for validity (Whittemore et al., 2001).

RESULTS

Themes

Eight themes emerged from the data and were divided into the two aims of this study. The following six themes emerged from the first aim of the study, which was to explore grand multiparous women’s perceptions of nursing care during childbirth: (1) providing welcome care, (2) offering choices, (3) following birth plans, (4) establishing trust and rapport, (5) being an advocate, and (6) providing reassurance and support. The following two themes emerged from the second aim of the study, which was to explore grand multiparous women’s perceptions of nurses’ use of technology during childbirth: (1) relying on electronic fetal monitors (EFMs) and assessments versus nursing presence and (2) having epidurals coupled with loss of bodily cues.

Perceptions of Nursing Care During Childbirth

Providing welcome care.

The mothers of this study overwhelmingly welcomed professional labor support from intrapartum nurses. The mothers articulated that their knowledge had grown and developed as each birth of a child was added to their repertoire of birth experiences. They were eager to seek out a relationship with a nurse because, as Jean (mother of six children) noted, “She [the nurse] knew what she was doing and I could call on her when the labor got tough.” The participants’ perception of nurses providing welcome care is further exemplified in Jean’s additional comments:

[Labor] was a scary experience, but she [the nurse] helped it. It was like having my mom there, she was that good . . . I preferred having her there and my mom outside in the hall. The nurse kept her cool during the whole time.

The women also described their perceptions of the presence of their husband and family members as it changed over the course of their numerous births. Although the women were grateful for their husbands’ and families’ help, they preferred a nurse’s care when their labor progressed to a more intense point. Having more children did not make a difference in their preference for a nurse’s care; in fact, a nurse’s welcome care often made the husband or family members more relaxed about the experience and placed less emphasis on the birth as a novel experience. As most of the study participants described, when their labor became intense, they welcomed the nurse’s care because the nurse knew what to do. These perceptions are illustrated in the following comments from participants:

[It] was more effective to have the nurse coach than my husband . . . She really knew what she was doing, she got right down to my level, not in my face but right there . . . kept me calm, kept me breathing . . . I think he [husband] got more laid back [with each successive birth]. (Cindy, mother of eight children)

My husband is a very supportive husband, and we went through all the birthing classes together. He learned everything and paid really close attention, and I can remember when we went in to have our first baby, the nurse commented that she had never seen such an attentive husband doing what he was supposed to do. But, even though he was very good at that, it would get to a point in the labor when it was starting to get serious. I wanted the nurse. (Loree, mother of six children)

No, he [husband] didn’t get better [in providing labor support for subsequent births]. It was my fifth baby. He was going to school and he kept reading a book between [my] breathing [techniques to manage the pain of labor], and I said, “If you don’t put that book down, it’s going to be out in the hallway.” He did put it down. (Margene, mother of 11 children)

Offering choices.

The mothers described wanting a nurse who offered them choices during labor, a time during which the mothers often felt they had little control. As Cindy (mother of eight children) noted, “[I was] doing the natural birth, trying to get comfortable. You know. Sometimes, I remember having really good nurses that would check on you often, seeing if you need anything, bringing you crushed ice.”

One of the participants was a Russian immigrant and had given birth in both Russian and U.S. hospitals. The tangible support of being offered choices during labor was meaningful for Velena (mother of 11 children; nine babies born in Russia and two babies born in the United States). She reported, “In America, nurses treated me like I was a queen.” In response to this statement, we asked Velena, “What did an American nurse do for you that made you feel like a queen?” She replied, “They asked me if I would like water.” Being offered even such a simple choice as a glass of water to drink was significant to Velena. She described how, in Russia, where she gave birth to nine of her children, she was not allowed any choices. She said, “With each of my deliveries, they locked me in the hospital as I said good-bye to my husband.” Her husband then waited outside of the building while she labored without any support from family. “After the birth,” Velena described, “I would walk to the window from a very high floor and where I might say, ‘Vladimir, it’s a boy!’ It was like Romeo and Juliet.”

Following birth plans.

The women valued their birth plans and, during the study’s interviews, frequently referred to their plans. Most of the women reported that the nurses were aware of and followed their birth plans. Jean (mother of six children) described her appreciation for the nurses who supported her birth plan:

I could hear talking about the birth plan in the hallway . . . they followed it pretty well . . . . The nurse was there, she was another great nurse. She was an excellent coach . . . . I realized that the nurses do more work than the doctors. Wow, the nurses need to sign the baby’s birth certificate.

According to one of Lamaze International’s six healthy birth practices, walking, moving around, and changing positions throughout labor increase the baby’s ability to rotate and descend.

Establishing trust and rapport.

The mothers reported they were eager to develop a rapport and a trusting relationship early with the nurse, so that when their labor intensified, they could rely on the nurse’s personal care and expertise. The mothers who trusted their nurses also said they relied on the nurses for nonverbal cues that helped direct the mothers when doctors or other health-care providers made suggestions. For example, as Loree (mother of six children) described:

While the doctor was gone, the nurse said, “Honey, do you want to have this baby?” I said, “Yeah.” She said, “Trust me, then.” I said, “Okay, I trust you,” because at this point, my husband was doing no good. She goes, “I want you to turn around and get on your hands and knees,” . . . and instantly, I could feel him [the baby] move somehow . . . after that, when the doctor made suggestions, I looked at the nurse for her reaction . . . because I trusted her.

Loree’s experience not only supports laboring mothers’ need for a trusting relationship with nurses, but also reinforces the importance of nurses encouraging laboring mothers to move and change positions. According to one of Lamaze International’s (2009) six healthy birth practices, walking, moving around, and changing positions throughout labor increase the baby’s ability to rotate and descend. The Lamaze care practices are supported by research evidence and are based on recommendations from the World Health Organization.

However, some of the mothers in our study described a particular situation in which they distrusted or were displeased with the nurses. These mothers related how they believed that if they called the hospital ahead of time, soon after they went into labor and decided to go to the hospital, the doctor would be waiting there for them. They reported feeling disappointed with the nurses when they arrived at the hospital and the doctor was not there because the nurses had not yet notified the doctor. As Jean (mother of six children) described:

We called ahead and the nurses hadn’t bothered to call the doctor, and my labors go very fast, not much warning. I called in . . . they didn’t call [the doctor] . . . that one [birth experience] was kind of a mess . . . They wouldn’t believe me when I said, “Hey, this baby is coming quickly,” and when we got in there, they hadn’t called anybody.

Apparently, the mothers who called the hospital before their arrival did not know that most nurses typically do not call in the doctor until after the laboring woman has arrived and registered as a patient. This misunderstanding led to a distrust of the nurses.

Being an advocate.

The participants believed that it was important for nurses to advocate for mothers, particularly if the obstetric practitioner was unable or chose not to follow the women’s birth plan. Lorene (mother of six children) described an experience in which she was frightened and knew that the doctor was busy. However, her nurse advocated for her in the birthing room and served as the communication link between Lorene and her doctor. Lorene noted, “My nurse was a real blessing at that time she went to bat for me. She could tell the doctor what I needed. She was there looking at me, checking me, and listening to me.”

Providing reassurance and support.

Nearly all of the participants expressed fear of experiencing pain and of being alone during labor, even though they had had family members with them at all times during their births. They wanted nurses to be present to relieve their family members and to offer the mothers reassurance. The participants were grateful for the nurses’ reassuring messages such as, “You can do it.” They also believed that having a sense of security was imperative to manage labor and birth. For example, Micki (mother of eight children) described her perception of the need for a nurse’s reassurance:

A really good nurse will let you know that you are going to be fine . . . . That is the type of nurse a person wants . . . [a nurse who provides] reassurance that you are a completely capable individual even if you are not prepared . . . you can do it . . . . The very first time you are in labor, you are not sure that you are going [to] live through that experience.

A few of the mothers shared that Lamaze childbirth classes were helpful and provided the support they needed during labor. For example, Karen (mother of eight children) said:

When you feel secure and supported, then you are allowed to have those other [spiritual] feelings. If you are frightened or tense, how much diminished that feeling would be. So I think that is critical to learn ahead. I really enjoyed going to L and D [labor and delivery] classes like Lamaze.

Perceptions of Nurses’ Use of Technology During Childbirth

Relying on electronic fetal monitors and assessments versus nursing presence.

The mothers expressed varying viewpoints on the use of EFMs. The younger mothers expressed positive views toward the use of EFMs. For example, Lorene (mother of six children) said, “They [EFMs] were reassuring; I could hear my baby’s heartbeat.” In contrast, the older mothers expressed a negative view toward the use of EFMs. For example, Louise (mother of seven children) described the use of EFMs as annoying. Louise had given birth to her first two children in the 1960s and, after receiving anesthesia gas and experiencing the accompanied dry heaves, she was eager to experience natural childbirth for her subsequent births. In reply to our interview question about monitors, Louise said, “This [the use of EFMs] isn’t natural. I thought ‘natural’ was like you didn’t have anything. Because my deliveries were fairly short, I felt like they [EFMs] were meaningless to me, just an annoyance. They [EFMs] were in the way.”

Another participant, Kim (mother of eight children and grandmother of 22 grandchildren) said she had a favorable view of the use of EFMs until she witnessed the adverse effects of nurses’ sole reliance on EFMs to monitor the progress of labor. Kim had given birth to three children prior to the use of monitors. During her subsequent births in the 1970s and 1980s, when EFMs were placed at the bedside, Kim had a positive view of the monitor because it “brought the nurse in more often.” However, when her daughter recently gave birth, Kim noticed that EFMs were also placed at the nurses’ station, which, she believed, prevented the nurses from personally monitoring her daughter’s labor progress and from providing adequate care. Consequently, Kim’s perception of the use of EFMs changed to a negative viewpoint, as conveyed in her following narrative:

[I said to the nurses,] “Are you looking at my daughter’s face, seeing her squinting? Breathing heavy? Tossing and turning? Are you watching this? You are watching the monitor but you are not watching her.” The monitor didn’t pick it up when she started bleeding during labor. But her face sure showed it when she went completely pale in the face. She started hemorrhaging, and her face showed it before the monitor did . . . She went white, and all of a sudden, here comes a blood clot under her bed—and I am not exaggerating, her blood clot was this big—the size of a chicken . . . [It’s] great to have monitors, but don’t just sit at the desk and watch the monitor.

Having epidurals coupled with loss of bodily cues.

The mothers in our study experienced a low epidural rate of 23% and a low cesarean surgery rate of 6.7% during their birthing experiences. Although the women valued the importance of epidurals in reducing pain and often giving laboring women the ability to relax and give birth, they differed in their views of the use of epidurals. Several mothers had initially experienced giving birth naturally and, for their subsequent births, had received an epidural. These mothers felt that, compared to their natural births, having an epidural led to the nurse attending to them less often. They also experienced the loss of a sense of control and of bodily cues. Three subthemes emerged from the narratives of these mothers who had received an epidural and compared the experience to their natural births: (1) a loss of independence, because they relied on the nurse to tell them what stage of labor they were in and what to do; (2) difficulty pushing, because they could not synchronize with their body’s cues, such as pain and contractions, as they pushed; (3) the nurse did not attend to them as often. These three subthemes are evident in the following narratives from participants:

[For the birth of my] sixth baby, I am not feeling anything [because of the epidural] . . . . I had to rely on the nurse to tell me where I was at [in my stage of labor] . . . I couldn’t gauge where I was anymore. (Lorene, mother of six children)

[For the birth of my] fifth baby . . . I didn’t like it [the epidural]. I wasn’t in control. I didn’t know what was going on. It felt like I was pushing 10 times harder, because to me the bearing-down pain [during my previous natural childbirth experiences] helped give that “hmmm” with the contractions, but with this [the epidural] I couldn’t feel . . . I had to push longer. With the other kids, I pushed once or twice . . . they were out. With this one, I had to push 15 or 20 minutes. It was harder to push, and I felt like I was more exhausted. (Kim, mother of eight children)

Less [labor support] with an epidural, they leave you alone because they don’t need to worry about you anymore. (Margene, mother of 11 children)

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

This study revealed many helpful findings. One of the most interesting and unexpected finding was that the participants believed that most of their nurses were aware of and followed their birth plan. Nurses often have a “strong aversion” to birth plans and often feel mothers with birth plans come with a “jinx” or a curse, which will lead to a bad birth outcome (Carlton, Callister, Christiaens, & Walker, 2009, p 52). It is possible that, although most of the mothers in our study claimed that the nurses followed their birth plan, the nurses were merely following the hospital’s routine, which aligned with the mothers’ birth plan. Childbirth educators can advocate for mothers by speaking with intrapartum nurses and encouraging them to follow mothers’ birth plans.

Some of the mothers’ negative perceptions of the use of EFMs illustrate the need for intrapartum nurses to balance caring labor support and keen assessment skills with labor technology. However, most hospitals only require certification in EFM, which is not evidence-based and does not require labor-support activities that are evidence-based (Kardong-Edgren, 2001). This practice may cause nurses to place more emphasis on what their employer requires than on what the laboring woman needs. Benner, Sutphen, Leonard, and Day (2010) noted that “in all aspects of nursing care, nurses are expected to perform complex, precise, and diverse technological interventions, keeping track of many machines and other devices” (p. 21). Benner et al. (2010) also noted that nurses must use attentiveness and clinical judgment to manage care. This care approach presents new challenges for all nurses, including labor and delivery nurses, who must “integrate nursing science and caring practices” as well as manage the technological aspects of care (p. 23). Instead of solely relying on technology, intrapartum nurses can be encouraged to use technology to augment their clinical skills to provide quality, face-to-face labor support.

Although the participants in this study understood the helpful aspect of epidurals in reducing labor pain, several of the women had a negative view of the use of epidurals because it restricted their feeling of control during labor, made it difficult to push during labor, and often led to the nurse not attending to them as often. When epidurals have dispersed into the spinal column and a favorable maternal and fetal status has been established, laboring women should be encouraged to move in bed as often as every 30–45 minutes (Zwelling, 2010). Nevertheless, nurses often believe that caring for a laboring woman who has an epidural is less intensive and easier to predict the birth of the newborn than caring for a woman who does not have an epidural. Nurses may perceive that the mother who has an epidural is not in pain and, therefore, may attend to her less frequently (Carlton et al., 2009). This study’s findings can offer nurses and educators ideas for discussion in their efforts to encourage and promote care practices that support laboring mothers.

Implications for Clinical Nursing Practice

The grand multiparous women in our study considered intrapartum nurses “knowledgeable,” and they valued their nurses’ expertise during the birth process as well as the routine of the hospital, even in the presence of supportive family members. Most of the participants expressed satisfaction and gratitude for the many hours nurses stood by their sides during their birthing experiences. This finding corresponds to the current literature, which states that women have greater satisfaction in labor when nurses give labor support (Hodnett et al., 2007).

Laboring women, including women who have previously experienced birth, desire to form a relationship with the nurse so that they can rely on the nurse to provide assistance when their labor intensifies. During labor, women often sense a loss of control; when nurses offer choices to women during labor, the women’s sense of control is enhanced. Nurses can be encouraged to advocate for laboring mothers to ensure adherence to the women’s birthing choice and birth plan. Intrapartum nurses can also coordinate perinatal activities with local childbirth educators and obstetric providers so that the information they give to patients is congruent.

The evolving technological demands during birth require a new paradigm of bedside care and labor support. As intrapartum nurses become aware of this new paradigm, they can diligently incorporate effective bedside assessments into their practice, integrating technological procedures with face-to-face assessments, without relying solely on technology.

During labor, women often sense a loss of control; when nurses offer choices to women during labor, the women’s sense of control is enhanced.

Implications for Childbirth Educators

Most of the grand multiparous women in our study shared positive memories of preparing for their first births by attending childbirth classes such as Lamaze. Indeed, many of the mothers were interested in and knowledgeable about Lamaze’s (2009) recommended healthy birth practices, such as walking, moving around, and changing positions throughout labor to help advance the descent of the baby. The mothers perceived that their preparation in childbirth classes was crucial in helping them delve into unknown territory such as birthing rooms. They appreciated learning about birth plans and using their plans during their birth experiences. However, research findings suggest intrapartum nurses have an aversion to birth plans (Carlton et al., 2009). To reverse nurses’ negative viewpoint of birth plans, childbirth educators can offer an in-service program to intrapartum nurses at the hospital where they serve. During the in-service programs, childbirth educators and intrapartum nurses can discuss topics such as birth plans and hospital routines. By increasing the consistency of information and care practices provided to women by childbirth educators, nurses, and health-care providers, expectant mothers will be able to reduce their fears and embrace the experience of birth.

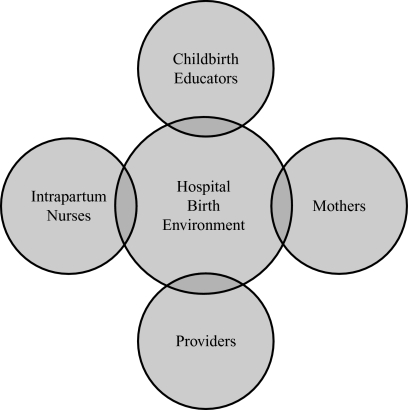

A common misunderstanding among the women in our study was the belief that if they called the hospital ahead of time, after they went into labor and before they arrived at the hospital, the doctor would be waiting there for them. Again, through hospital in-service programs and curriculum offered in childbirth classes, childbirth educators can provide a common link in ensuring consistent, reliable information and communication among expectant mothers, health-care providers, and hospital nurses (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Congruent communication links.

Note. Congruent communication links to ensure consistent, reliable information and communication among expectant mothers, childbirth educators, intrapartum nurses, and obstetric providers in the hospital environment.

CONCLUSION

In summary, grand multiparous women can offer a wealth of information regarding their accumulated years’ worth of birthing in hospitals. The grand multiparous women in our study shared many birthing experiences that illuminated the evolving use of technology and nursing care in U.S. hospitals over the years. Advances in the increasing use of technology in intrapartum care need to be carefully examined. Often, the demands of tending to labor technology can draw the nurse away from the laboring mother. To improve intrapartum-nursing practice, it is imperative to understand the nature of the hospital birth environment, where technology and nursing care intersect. The interview data retrieved from the grand multiparous women in our study offer valuable insights into the current state of intrapartum care in today’s high-technology hospital environments. Intrapartum nurses and childbirth educators can be instrumental in promoting natural, safe, and healthy births and providing congruent communication links in today’s high-technology birth environments in hospitals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to Roxanne Vandermause, PhD, RN, CARN, for sharing her expertise in qualitative methodologies and the resemblances associated with several of the qualitative traditions.

Biography

SUSAN E. FLEMING is a doctoral candidate in the College of Nursing at Washington State University in Spokane, Washington. Her research focuses on technology and the American birth experience. DENISE SMART is an assistant professor in the College of Nursing at Washington State University. She is also a lieutenant colonel in the Air National Guard with more than 21 years in the military, serving as a public health officer and chief of nursing services with the 141st Medical Group in Fairchild, Washington. Her research focuses on mother–baby care and lactation-related issues. PHYLLIS EIDE, a native of the Pacific Northwest, has been with the College of Nursing at Washington State University since 2002. In 2000, she earned a doctoral degree in nursing from the University of Colorado.

REFERENCES

- Adams E. D., Bianchi A. L.2008A practical approach to labor support Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 371106–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00213.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner P., Sutphen M., Leonard V., Day L. Educating nurses: A call for radical transformation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Carlton T., Callister L. C., Christiaens G., Walker D.2009Labor and delivery nurses’ perceptions of caring for childbearing women in nurse-managed birthing units MCN: The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing 34150–56. doi: 10.1097/01.NMC.0000343866.95108.fa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declercq E. R., Sakala C., Corry M. P., Applebaum S. Listening to Mothers II: Report of the second national U.S. survey of women’s childbearing experiences. New York, NY: Childbirth Connection; 2006. Retrieved from http://www.childbirthconnection.org/pdfs/LTMII_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hodnett E. D., Gates S., Hofmeyr G. J., Sakala C.2007Continuous support for women during childbirth Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 31–37. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardong-Edgren S. Using evidence-based practice to improve intrapartum care. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2001;30(4):371–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2001.tb01555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamaze International. Lamaze healthy birth practices. 2009. Jul, Retrieved from http://www.lamaze.org/ChildbirthEducators/ResourcesforEducators/CarePracticePapers/tabid/90/Default.aspx.

- Payant L., Davies B., Graham I. D., Peterson W. E., Clinch J.2008Nurses’ intentions to provide continuous labor support to women Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 374405–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano A. M., Lothian J. A.2008Promoting, protecting, and supporting normal birth: A look at the evidence Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 37194–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health. 2000;23(4):334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauls D. J. Measurement of perceptions of intrapartum nurses regarding professional labor support. Dissertation Abstracts International. 2000;61:5802. (Doctoral dissertation, Texas Woman’s University) [Google Scholar]

- Sauls D. J. Dimensions of professional labor support for intrapartum practice. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2006;38(1):36–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin P. Supportive care during labor: A guide for busy nurses. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2002;31(6):721–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart D. Attitudes, social support, and self-efficacy (ASE): A predictive model for vaginal birth intentions. Loma Linda, CA: Loma Linda University; 2004. (Doctoral dissertation) [Google Scholar]

- Varney H., Kriebs J. M., Gegor C. L. Varney’s midwifery. 4th ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Venes D., editor. Ed.Taber’s cyclopedia medical dictionary. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis (21st ed.) 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R., Chase S. K., Mandle C. L. Validity in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research. 2001;11(4):522–537. doi: 10.1177/104973201129119299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwelling E.2008The emergence of high-tech birthing Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 37185–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwelling E. Overcoming the challenges: Maternal movement and positioning to facilitate labor progress. Journal of Maternal-Child Health Nursing. 2010;35(2):72–78. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0b013e3181caeab3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]