Abstract

High affinity and selective S1P4 receptor (S1P4–R) small molecule agonists may be important proof-of-principle tools used to clarify the receptor biological function and effects to assess the therapeutic potential of the S1P4–R in diverse disease areas including treatment of viral infections and thrombocytopenia. A high-throughput screening campaign of the Molecular Libraries-Small Molecule Repository was carried out by our laboratories and identified (2Z,5Z)-5-((1-(2-fluorophenyl)-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrol-3-yl)methylene)-3-methyl-2-(methylimino) thiazolidin-4-one as a promising S1P4–R agonist hit distinct from literature S1P4–R modulators. Rational chemical modifications of the hit allowed the identification of a promising lead molecule with low nanomolar S1P4–R agonist activity and exquisite selectivity over the other S1P1-3,5–Rs family members. The lead molecule herein disclosed constitutes a valuable pharmacological tool to explore the effects of the S1P4–R signaling cascade and elucidate the molecular basis of the receptor function.

Keywords: S1P4 receptor, selective small molecule S1P4–R agonists, thrombocytopenia, viral infections

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) is a bioactive lysophospholipid metabolite formed from ceramide and sphingosine in various cells including mast cells, platelets, and macrophages in response to diverse stimuli such as growth factors, cytokines, G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) agonists and antigens. S1P regulates a broad variety of cellular signaling pathways resulting in calcium homeostasis, actin polymerization, cell proliferation, motility and survival. The biological responses of S1P are mediated by the activation of cell membrane GPCRs as well as by the modulation of incompletely characterized intracellular targets. The GPCRs responsive to S1P include GPR3,6,12 receptor family, and five receptor subtypes of the endothelial differentiation genes (Edg) family termed S1P1-5 (formally Edg-1, -5, -3, -6, and -8).1-5

Recently, S1P1-5 receptor (S1P1-5–Rs) family has gained growing attention due to its physiological and pathophysiological role in immune function, cardiovascular system and cancer invasion.2 S1P receptor agonists have been demonstrated to alter immunological responses and inhibit lymphocyte recirculation.3-8 Noteworthy, numerous high affinity S1P1–R molecule agonists are currently in preclinical and clinical trials as immunosuppressive drug candidates for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Amongst them, S1P1,3-5–Rs pan-agonist Fingolimod (FTY720) has been recently approved by the FDA as orally active prodrug for the treatment of multiple sclerosis.9-10

Understanding S1P-modulated pathways in the endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells is a critical ongoing area of investigation. Importantly, S1P-dependent activation of vascular endothelial S1P1,3–Rs promotes vasorelaxation responses and antagonizes vasoconstriction by activation of the endothelial isoform of nitric oxide synthase and subsequent production of nitric oxide via the small GTP-binding cytoskeleton signaling protein Rac1. In contrast, S1P2,3–Rs in smooth muscle cells can elicit vasoconstriction responses through the activation of the small G-protein RhoA signaling cascade, particularly at high concentrations of S1P.4,11

Interestingly, molecules targeting S1P-metabolizing enzymes have been recently proposed as innovative potential therapeutics for viral infections.12

Additionally, sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1)/S1P signaling cascade has been recently linked to the transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (H1F-1α) in distinct tumor cell lines. Given the key role of H1F-1α in the adaptive changes to hypoxia including angiogenesis and metastasis, SphK1/S1P pathway has been proposed as an innovative target for therapeutic intervention in oncology, thus demanding further studies to fully elucidate the function of S1P and its target receptors upon Sphk1 activation.13

Amongst S1P1-5–Rs, the S1P4–R couples to Gαi, Gαo and Gα12/13 proteins leading to the stimulation of MAPK/ERK signaling pathways, as well as PLC and Rho-Cdc42 activation.14-15

S1P4–R is predominantly expressed in lymphocyte-containing tissues including the thymus, spleen, bone marrow, appendix, peripheral leukocytes, lung, and shows approximately 100–600-fold reduced binding affinity for S1P compared to the other S1P-R family members.16

Although poorly characterized, the contribution of S1P4–R to the immune response is becoming increasingly evident. It has been demonstrated that S1P induces migratory response of murine T-cell lines expressing both S1P1–R and S1P4–R mRNA; in D10.G4.1 and EL-4.IL-2 murine cells, S1P-induced migration was significantly inhibited by treatment with (S)-FTY720-phosphate, a potent agonist at S1P1–R and S1P4–R Additionally, S1P-induced T-cell migration involved the activation of Rho family small GTPase, Cdc 42 and Rac, in murine CHO cells co-expressing S1P4–R and S1P1–R on the cell surface. These results have suggested that the association of S1P4–R and S1P1–R may play an important role in the migratory and recirculation response of T-cells toward S1P.1 Additional studies demonstrated that the intratracheal delivery of the synthetic sphingosine analogs with mixed activity over S1P1,3-5–Rs efficiently inhibited the T-cell response to influenza virus infection by impeding the accumulation of dendritic cells (DCs) in draining lymph nodes. The inhibitory effects were not observed upon specific chemical activation of S1P1–R, and persisted in S1P3–R null mice. Based on these findings and on the evidence that S1P4–R is highly expressed in DCs in contrast to S1P5–R expression, it has been hypothesized that the S1P4–R modulation in the lung may be effective at controlling the immunopathological response to viral infections.17,18

Moreover, while the S1P effects on the systemic vasoregulation are predominantly mediated by S1P1,2,3–Rs subtypes, the S1P4–R has been demonstrated to have a key role in S1P-induced vasoconstriction in the rat pulmonary circulation by activating Rho kinase.19

Both in vitro and in vivo experiments in animal models have recently indicated an additional potential therapeutic application of S1P4–R molecule modulators in the terminal differentiation of megakaryocytes. Notably, the application of S1P4–R antagonist might be exploited for inhibiting potentially detrimental reactive thrombocytosis, whereas S1P4–R agonists represent a potential therapeutic approach for stimulating platelet repopulation after thrombocytopenia.20

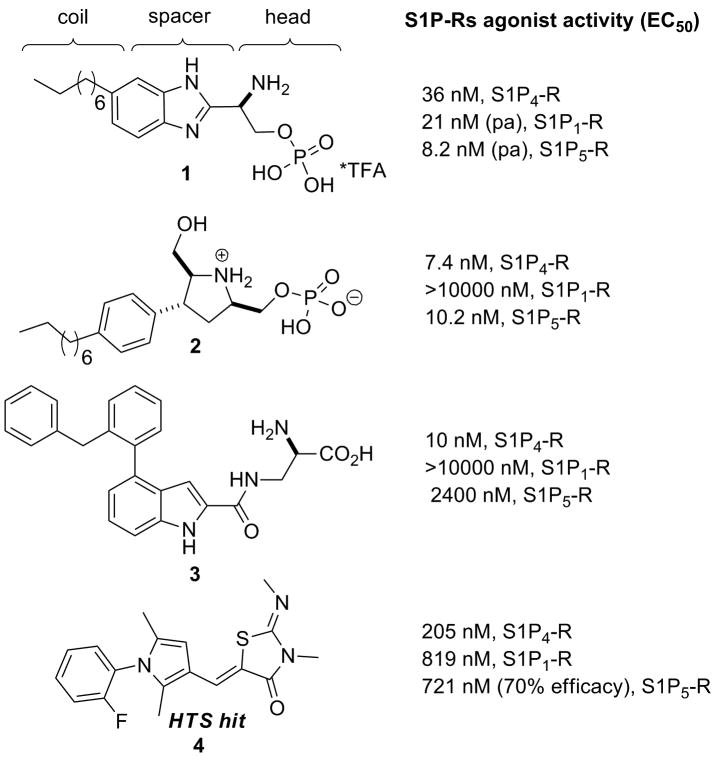

To date, despite the S1P4–R therapeutic potential, the in vivo function of the target receptor remains largely unknown. Indeed, the limited number of known selective S1P4–R small molecule antagonists is restricted to the molecules recently disclosed by our research group,21,22 whereas promiscuous selectivity profile is found for the S1P4–R agonists reported in the literature. Amongst them, benzymidazole derivative 1 was reported as a potent S1P4–R agonist with low nanomolar partial agonist (pa) activity on S1P1,5–Rs subtypes (Figure 1).23 The constrained azacyclic analog of FTY720 2 was described as a potent non selective S1P4,5–Rs agonist (Figure 1).24 Remarkably, the indole-alanine derivative 3 has been reported as a potent S1P4–R agonist with good selectivity against the other S1P family receptors (Figure 1).25 However, 3 and its structurally related compounds have been also studied as high affinity modulators of glycine recognition site on the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor complex.26

Figure 1. S1P4–R agonist modulators.

In an effort to discover novel and selective S1P4–R agonists, a high-throughput screening (HTS) campaign of the Molecular Libraries-Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR) was carried out by our laboratories and identified the hit (2Z,5Z)-5-((1-(2-fluorophenyl)-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrol-3-yl)methylene)-3-methyl-2-(methylimino) thiazolidin-4-one 4 endowed with moderate S1P4–R agonist activity, modest selectivity against S1P1,5–Rs and no activity over S1P2,3–Rs at concentrations up to 25 μM (Figure 1).

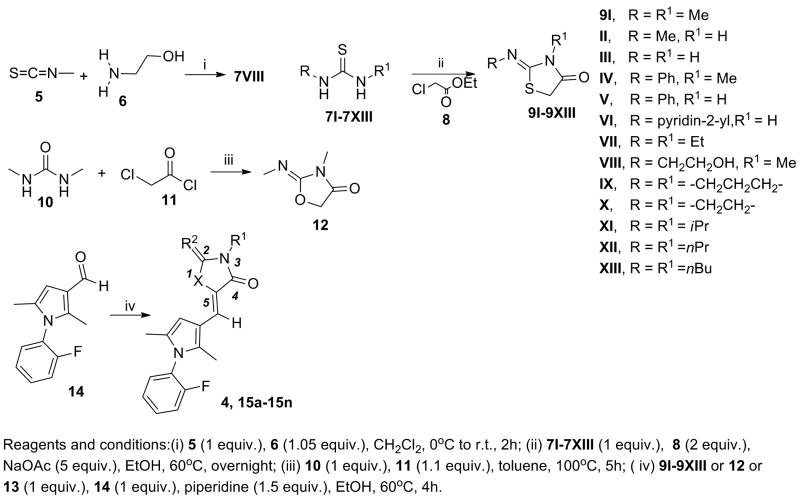

The structural integrity and biological activity of the original hit 4 were confirmed by re-synthesizing the title compound (Scheme 1). Reaction of commercially available dimethylthiourea 7I with ethylchloroacetate 8 provided 3-methyl-2-(methylimino)-thiazolidin-4-one 9I which was then reacted with pyrrole-3-carbaldehyde 14. The (2Z,5Z)-configuration of 2-methylimino and the olefinic bond of 4 was verified by 1H,1H-NOESY experiment.27

Scheme 1. Synthesis of analogs 15a-15n.

To start our SAR studies on 4, we prepared a series of derivatives varying the polar thiazolidin-4-one head while maintaining the 2-fluorophenyl coil and the 2,5-dimethylpyrrol-3-yl spacer as constant moieties. Representative examples of the explored modifications are represented by compounds 15a-15n (Scheme 1, Table 1). 15a-15e, 15g, 15j-15n were synthesized using the appropriate commercially available thioureas (7II-7VII, 7IX-7XIII) and 8 to give the corresponding thizolidin-4-ones (9II-9VII, 9IX-9XIII). The synthesis of compound 15h involved the preparation of the thiourea precursor (7VIII) from methyl isothiocyanate (5) and 2-ethanolamine (6), followed by the synthesis of the corresponding thiazolidin-4-one (9VIII). 15i was synthesized from oxazolidin-4-one (12) obtained by reaction of dimethyl urea (10) with chloro acetylchloride (11), while compound 15f was easily obtained from commercially available 3-methylthiazolidine-2,4-dione (13). Final condensation of the aforementioned 5-membered ring intermediates (9II-9XIII, 12, 13) with 14 furnished the desired products 15a-15n.

Table 1. S1P4–R agonist activity of compounds 15a-15n (EC50 nM).

| cpd | R2 | R1 | X | EC50 (nm)α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15a | NMe | H | S | 3600 |

| 15b | NH | H | S | NA |

| 15c | NPh | Me | S | 2800 |

| 15d | NPh | H | S | NA |

| 15e | N(pyridin-2-yl) | H | S | 2100 (70%) β |

| 15f | O | Me | S | NA |

| 15g | NEt | Et | S | 250 |

| 15h | NCH2CH2OH | Me | S | 306 |

| 15i | NMe | Me | O | NA |

| 15j | NCH2CH2CH2 | S | NA | |

| 15k | NCH2CH2 | S | NA | |

| 15l | NiPr | iPr | S | NA |

| 15m | NnPr | nPr | S | NA |

| 15n | NnBu | nBu | S | NA |

Data are reported as mean of n = 3 determinations.

Percentage of response.

NA = not active at concentrations up to 25 μM.

The biological results of the obtained molecules are listed in Table 1.28

When the methyl group was removed from either position 3 (15a) or both positions 2 and 3 (15b), the potency decreased substantially. Moreover, the 3-unsubstituted 2-phenylimino analog (15d) was devoid of activity, and significantly reduced potency was found for the corresponding 2-(pyridin-2-yl) derivative (15e) as well as for the 3-methyl-2-phenylimino analog (15c). Compounds containing bulky alkylic groups at both positions 2 and 3 were devoid of potency (15l-15n). By contrast, similar activity to the hit was found in the presence of ethyl groups at the same positions (15g). Noteworthy, the analog containing the polar 2-hydroxyethyl substituent at position 2 (15h) was only 1.5-less potent than the hit. Taken all together, these data suggest that bulky alkylic groups with different polarity are tolerated at position 2, while position 3 may be involved in a lipophilic interaction within a smaller binding pocket. Replacement of the 2-(methylimino)thiazolidin-4-one head with thiazolidine-2,4-dione (15f) or oxazolidin-4-one (15i) led to complete loss of activity. Interestingly, conformationally restricted analogs (15j, 15k) were also inactive. To note, the 2-alkylimino functionality of 15j and 15k is locked into the E-geometry suggesting that the Z-configuration at position 2 may be a binding requirement.

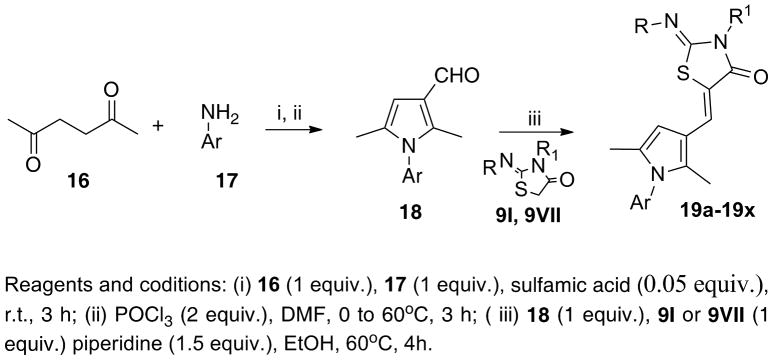

Successively, we synthesized compounds 19a-19x (Scheme 2, Table 2) in order to optimize the lipophilic aryl coil while keeping the thiazolidin-4-one polar head and the 2,5-dimethylpyrrol-3-yl spacer as in the hit and 15g. The synthesis of these derivatives is depicted in Scheme 2. Condensation of hexadione 16 with the appropriate amine 17 furnished the corresponding N-substituted-2,5-dimethylpyrrole, which yielded the pyrrol-3-carbaldehyde derivative 18 via Vilsmeier-Haack reaction. Condensation of 18 with the opportune thiazolidin-4-one (9I or 9VII) afforded the desired products 19a-19x. The biological responses of the obtained compounds are listed in Table 2.28

Scheme 2. Synthesis of analogs 19a-19x.

Table 2. S1P4–R agonist activity of compounds 19a-19x (EC50 nM).

| cpd | Ar | R | R1 | EC50 (nm) α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19a | 2-chlorophenyl | Me | Me | NA |

| 19b | 2-bromophenyl | Me | Me | NA |

| 19c | 2-methylphenyl | Me | Me | NA |

| 19d | 3-fluorophenyl | Me | Me | 1600 (60%) β |

| 19e | 4-fluorophenyl | Me | Me | 433 |

| 19f | 3-cyano-4-fluoro-phenyl | Me | Me | 3200 (50%) β |

| 19g | 4-methoxy-3-(trifluoromethyl) phenyl | Me | Me | NA |

| 19h | 2-methoxy-5-methyl phenyl | Me | Me | NA |

| 19i | 2,4-difluorophenyl | Me | Me | 210 |

| 19j | 2,4-dimethylphenyl | Me | Me | NA |

| 19k | 4-chloro-2-fluorophenyl | Me | Me | 440 |

| 19l | phenyl | Et | Et | 602 |

| 19m | pyridin-2-yl | Me | Me | 1800 |

| 19n | naphthalen-1-yl | Me | Me | NA |

| 19o | naphthalen-1-yl | Et | Et | NA |

| 19p | 3-fluoro-pyridin-2-yl | Me | Me | 3100 (70%) β |

| 19q | 3-fluoro-pyridin-2-yl | Et | Et | 5400 (70%) β |

| 19r | benzyl | Me | Me | 262 |

| 19s | 2-flurobenzyl | Me | Me | 72 |

| 19t | 2,6-difluorobenzyl | Me | Me | 92 |

| 19u | 2,6-difluorobenzyl | Et | Et | 314 |

| 19v | 2,4-diflurobenzyl | Me | Me | 147 |

| 19w | 1-phenyleth-1-yl | Me | Me | 660 (20%) β |

| 19x | 1-phenyleth-1-yl | Et | Et | NA |

Data are reported as mean of n = 3 determinations.

Percentage of response.

NA = not active at concentrations up to 25 μM.

When the ortho-fluorine of the hit was replaced with either chlorine, bromine or methyl group (19a, 19b, 19c), no activity was observed. Interestingly, the 3-fluorophenyl isomer (19d) was 8-fold less potent, while the 4-fluorophenyl derivative (19e) showed only 2-fold lower potency than the hit. Compounds containing variously disubstituted phenyl rings including but not limited to the examples herein reported (19f-h, 19j) were found to be inactive or have significantly reduced activity, thus suggesting that polar and bulky groups in this region are detrimental for the activity. Consistent with this hypothesis, naphthalenyl derivatives (19n, 19o) were inactive. Interestingly, amongst the disubstituted phenyl rings, the 4-chloro-2-fluorophenyl analog (19k) was only 2-fold less potent and the 2,4-difluorophenyl analog (19i) was equipotent to the hit, while the unsubstituted phenyl derivative (19l) was only 2-3-fold less potent than 15g. The fluorine was therefore identified as suitable bioisoster of the hydrogen atom at positions 2,4 of the phenyl ring. By contrast, replacement of 2-fluophenyl with the basic pyridinyl ring (19m) resulted in 9-fold decreased potency than the hit; reduced activity compared to the hit and 15g, was also found for 3-fluoropyridinyl derivatives (19p-19q). Elongation of the hydrophobic coil by insertion of a methylene at the pyrrole nitrogen was tolerated as observed for the benzyl (19r), 2-flurobenzyl (19s), 2,6-difluorobenzyl (19t-19u) and 2,4-difluorobenzyl (19v) analogs. However, the introduction of a methyl group at the benzylic carbon negatively affected the potency (19w, 19x) probably as a result of a steric clash within the binding site or due to conformational changes in the molecule.

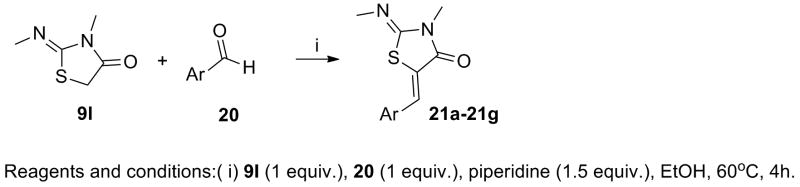

The study of the 2,5-dimethylpyrrol-3-yl spacer was carried out conserving the head 3-methyl-2-(methylimino)thiazolidin-4-one as in the hit, and selecting the easily accessible coil fragments from the active molecules. The synthesis of these derivatives is outlined in Scheme 3. The condensation of thiazolidin-4-one 9I with commercially available carbaldehydes 20 under the conditions previously described furnished the desired products 21a-21g that were submitted for biological activity (Table 3).28

Scheme 3. Synthesis of analogs 21a-21g.

Table 3. S1P4–R agonist activity of compounds 21a-21g (EC50 nM).

| cpd | Ar | EC50 (nm) α |

|---|---|---|

| 21a |

|

NA |

| 21b |

|

NA |

| 21c |

|

3800 |

| 21d |

|

NA |

| 21e |

|

NA |

| 21f |

|

NA |

| 21g |

|

NA |

Data are reported as mean of n = 3 determinations.

NA = not active at concentrations up to 25 μM.

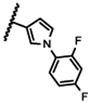

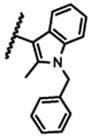

The 5-methylpyrazol-4-yl derivative (21c) was 18-fold less potent than the hit. Complete loss of activity was observed for the 3,5-dimethyl and the unsubstituted pyrazol-4-yl analogs (21a-b) as well as for the 2,5-unsubstituted pyrrol-3-yl (21d-21f) and the 2-methyl indol-3-yl (21g) analogs, thus indicating that the 2,5-dimethylpyrrol-3-yl moiety is an essential molecular feature for the receptor binding.

The functional activity of the most active compounds was tested against S1P1-3,5–Rs subtypes (Table 4). The phenyl 3-ethyl-2-(ethylimino)thiazolidin-4-one derivative 19l showed increased S1P1,5–Rs activity, while retaining selectivity towards S1P2-3–Rs compared to the hit. Interestingly, the benzyl derivatives 19r-19v showed high to low nanomolar activity for S1P1,5–Rs; some activity versus S1P2–R and S1P3–R was also observed for compounds 19r-19t. The 4-fluorophenyl derivative 19e displayed 2-fold decreased potency against S1P1–R, while keeping similar activity pattern for S1P2,3,5–Rs compared to the hit. Significantly improved selectivity profile was found for the 2-fluorophenyl 3-methyl-2-((2-hydroxyethyl)imino) derivative 15h which showed only a weak activity for S1P1–R and S1P5–R subtypes. Similarly, the 4-chloro-2-fluorophenyl derivative 19k showed only modest activity against S1P1,5–Rs. Interestingly, the introduction of ethyl groups at the thiazolidin-4-one head of the hit conferred to 15g exquisite selectivity against all S1P1-3,5–Rs subtypes. Additionally, a good potency/selectivity profile was observed in the presence of 2,4-difluorophenyl as lipophilic coil with 19i displaying high selectivity against S1P1–R (21-fold), and no activity against S1P2-3,5-Rs up to 25 μM.

Table 4. S1P1-5–Rs selectivity counter screen of selected compounds.

| cpd | EC50 nM α | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1P4 | S1P1 | S1P2 | S1P3 | S1P5 | |

| 4 | 205 | 819 | NA | NA | 721 (70%) β |

| 15g | 250 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 15h | 306 | 20% (8.3μM) χ | NA | NA | 60% (8.3μM) χ |

| 19e | 433 | 1800 (70%) β | NA | NA | 652 (50%) β |

| 19i | 210 | 4470 | NA | NA | NA |

| 19k | 440 | 3010 | NA | NA | 3400 |

| 19l | 602 | 68 | NA | NA | 237 |

| 19r | 262 | 720 | 3650 | NA | 144 |

| 19s | 72 | 250 | 60% (25μM) χ | 25%(25μM) χ | 51 |

| 19t | 92 | 34 | 120% (25μM) χ | 70%(25μM) χ | 34 |

| 19u | 314 | 18 | NA | NA | 22 |

| 19v | 147 | 287 | NA | NA | 37 |

Data are reported as mean of n = 3 determinations.

Percentage of response.

Concentration producing the reported percentage of response.

NA = not active at concentrations up to 25 μM.

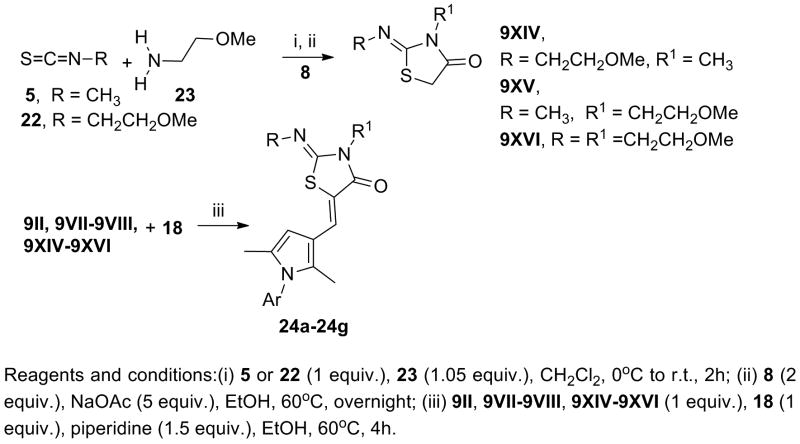

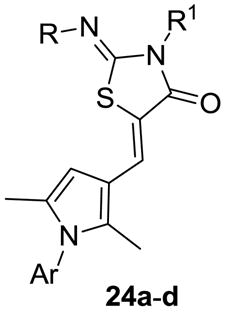

The SAR at the polar head were further investigated by the synthesis of derivatives 24a-24g (Scheme 4, Table 5) containing the 2,5-dimethylpyrrol-3-yl moiety and either the benzyl or 2,4-difluorophenyl nucleus, the latter selected as the most suitable lipophilic coil in terms of receptor biological profile. Compounds 24a-24c were synthesized as previously described starting from the opportune thiazolidin-4-ones (9II, 9VII-9VIII, Scheme 1) and the pyrrol-3-carbaldehydes (18, Scheme 2). Analogously, the synthesis of 24d-24g was accomplished starting from the appropriate isothiocyanate (5, 22) and 2-methoxyethanamine (23) to provide the corresponding thiazolidin-4-ones 9XIV-9XVI which were successively reacted with appropriate pyrrol-3-carbaldehyde (18) to give the final products (Scheme 4). The S1P4–R functional activity of the monomethyl 24a and the diethyl 24b 2,4-difluorophenyl derivatives paralleled those of the 2-fluorophenyl series 15a and 15g. The benzyl 2-(2-hydroxyethyl)imino derivative 24c had similar potency compared to the corresponding 2-fluorophenyl analog 15h. Interestingly, the 2-(2-methoxyethyl)imino analog 24d showed 6-fold increased activity compared to 24c, thus prompting us to synthesize the 2,4-difluorophenyl analog 24f (CYM50308).29 Notably, 24f was respectively 4- and 30-fold more potent than 19i and the regioisomer 24g.30 These findings support our working hypothesis that larger polar groups are better tolerated at position 2 of the thizolidin-4-one head, as further corroborated by the lack of activity shown by the di-substituted 3-(2-methoxyethyl)-2-(2-methoxyethyl)imino derivative 24e. To test for selectivity, 24b, 24d and 24f were assayed on S1P1-3, 5–Rs subtypes (Table 6). The 2,4-difluorophenyl 3-ethyl-2-(ethylimino) derivative 24b showed decreased selectivity against S1P1,5–Rs compared to the dimethyl (19i) and the 2-fluorophenyl (15g) counterparts. The benzyl 3-methyl-2-(2-methoxyethyl)imino derivative 24d was selective against S1P1-3–Rs but displayed only 3-fold selectivity versus S1P5–R. Remarkably, the 2,4-difluorophenyl 2-(2-methoxyethyl)imino derivative 24f elicited exquisite selectivity profile displaying 37-fold selectivity against S1P5–R and no appreciable activity over S1P1-3–Rs subtypes at concentrations up to 25 μM.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of analogs 24a-24g.

Table 5. S1P4–R agonist activity of compounds 24a-24g (EC50 nM).

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cpd | R | R1 | Ar | EC50 (nm) α |

| 24a | Me | H | 2,4-difluorophenyl | 1000 |

| 24b | Et | Et | 2,4-difluorophenyl | 104 |

| 24c | CH2CH2OH | Me | benzyl | 396 |

| 24d | CH2CH2OMe | Me | benzyl | 68 |

| 24e | CH2CH2OMe | CH2CH2OMe | benzyl | NA |

| 24f | CH2CH2OMe | Me | 2,4-difluorophenyl | 56 |

| 24g | Me | CH2CH2OMe | 2,4-difluorophenyl | 1700 |

Data are reported as mean of n = 3 determinations.

NA = not active at concentrations up to 25 μM.

Table 6. S1P1-5–Rs selectivity counter screen of compounds 24b, 24d, 24f (EC50 nM).

| cpd | EC50 (nm) α | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1P4 | S1P1 | S1P2 | S1P3 | S1P5 | |

| 24b | 104 | 816 | NA | NA | 6180 |

| 24d | 68 | 85% χ | NA | NA | 196 (80%) β |

| 24f | 56 | NA | NA | NA | 2100 |

Data are reported as mean for n = 3 determinations.

Percentage of response.

Percentage of inhibition at 25μM.

NA = not active at concentrations up to 25 μM.

In summary, we have reported the discovery, synthesis and SAR analysis of novel selective small molecule S1P4–R functional agonists based on a (2Z,5Z)-5-((pyrrol-3-yl)methylene)-3-alkyl-2-(alkylimino)thiazolidin-4-one chemotype structurally unrelated to the known S1P4–R modulators. Systematic SAR studies of the MLSMR hit 4, endowed with moderate S1P4–R potency, high selectivity over S1P2,3–Rs but submicromolar activity towards both S1P1,5–Rs, led to the identification of a full spectrum selective S1P4–R agonist compound 24f (CYM50308). Indeed, the disclosed lead molecule 24f displayed low nanomolar S1P4–R agonist activity and exquisite selectivity over the other S1P–Rs subtypes. Noteworthy, 24f provides a novel valuable pharmacological tool to explore the effects of the S1P4–R signaling cascade and elucidate the molecular basis of the in vivo receptor function. Details of further research efforts will be communicated in due course.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health Molecular Library Probe Production Center grant U54 MH084512 (Edward Roberts, Hugh Rosen) and AI074564 (Michael Oldstone, Hugh Rosen). We thank Mark Southern for data management with Pub Chem, Pierre Baillargeon and Lina DeLuca (Lead Identification Division, Scripps Florida) for compound management.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Matsuyuki H, Maeda Y, Yano K, Sugahara K, Chiba K, Kohno T, Igarashi Y. Cell Mol Immunol. 2006;3:429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inagaki Y, Pham T, Fujiwara Y, Kohno T, Osborne DS, Igarashi Y, Tigyi G, Parrill AL. Biochem J. 2005;389:187. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marsolais D, Rosen H. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:297. doi: 10.1038/nrd2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jo E, Sanna MG, Gonzalez-Cabrera PJ, Thangada S, Tigyi G, Osborne DA, Hla T, Parrill AL, Rosen H. Chem Biol. 2005;12:703. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanna G, Liao J, Jo E, Alfonso C, Ahn M, Peterson MS, Webb B, Lefebvre S, Chun J, Gray N, Rosen H. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marsolais D, Hahm B, Walsh KB, Edelmann KH, McGavern D, Hatta Y, Kawaoka Y, Rosen H, Oldstone MB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(5):1560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812689106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alfonso C, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Rosen H. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:149. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei SH, Rosen H, Matheu MP, Sanna MG, Wang S, Jo E, Wong C, Parker I, Cahalan M. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1228. doi: 10.1038/ni1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cusack K, Stoffel RH. Curr Opin Drug Discovery Dev. 2010;13:481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swedin H. FDA Advisory Committee Unanimously Recommends Approval of Novartis Investigational Treatment FTY720 to Treat Relapsing Remitting MS. Novartis Press Release, PR Newswire; Jun 10, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Igarashi J, Michel T. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82:212. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seo YJ, Blake C, Alexander S, Hahm B. J Virol. 2010;84:8124. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00510-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ader I, Malavaud B, Cuvillier O. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3723. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toman RE, Spiegel S. Neurochem Res. 2002;27:619. doi: 10.1023/a:1020219915922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohno T, Matsuyuki H, Inagaki Y, Igarashi Y. Genes Cells. 2003;8:685. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mandala S, Hajdu R, Bergstrom J, Quackenbush E, Xie J, Milligan J, Thornton R, Shei GJ, Card D, Keohane C, Rosenbach M, Hale J, Lynch CL, Rupprecht K, Persons W, Rosen H. Science. 2002;296:346. doi: 10.1126/science.1070238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maeda Y, Matsuyuki H, Shimano K, Kataoka H, Sugahara K, Kenji Chiba K. J Immunol. 2007;178:3437. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marsolais D, Hahm B, Edelmann KH, Walsh KB, Guerrero M, Hatta Y, Kawaoka Y, Roberts E, Oldstone MB, Rosen H. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:896. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.048769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ota H, Ito M, Beutz MA, Homma N, Holberg G, Abe K, Oka M, McMurtry IF. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:A6244. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golfier S, Kondo S, Schulze T, Takeuchi T, Vassileva G, Achtman AH, Gräler MH, Abbondanzo SJ, Wiekowski M, Kremmer E, Endo Y, Lira SA, Bacon KB, Lipp M. FASEB J. 2010;24:4701. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-141473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urbano M, Guerrero M, Zhao J, Velaparthi S, Schaeffer MT, Brown S, Rosen H, Roberts E. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:5470. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.06.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guerrero M, Urbano M, Velaparthi S, Zhao J, Schaeffer MT, Brown S, Rosen H, Roberts E. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:3632. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.04.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clements JJ, Davis MD, Lynch KR, Macdonald TL. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:4903. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanessian S, Charron G, Billich A, Guerini D. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:491. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azzaoui K, Bouhelal R, Buehlmayer P, Guerini D, Koller M. U.S. Patent 7,754,896. 2010 July 13;

- 26.Urwyler S, Floersheim P, Roy BL, Koller M. J Med Chem. 2009;52:5093. doi: 10.1021/jm900363q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.1H,1H-NOESY spectrum was acquired using spectrometer Bruker DRX-600 equipped with a 5 mm DCH cryoprobe. NOE interaction was not observed between the methyl groups located at position 2 and 3 of the thiazolidin-4-one nucleus, thus indicating Z configuration of the 2-methylimino bond (numeration as in Scheme 1). The H atom of the olefinic bond at position 5 (numeration as in Scheme 1) gave rise to a cross-peak with the methyl group at position 2 but not with the H atom at position 4 of the 2,5-dimethylpyrrol-3-yl nucleus; Z configuration was therefore assigned to the aforementioned bond.

- 28.The biological assays were performed using Tango S1P4-BLA U2OS cells containing the human Endothelial Differentiation Gene 6 (EDG6; S1P4–R) linked to a GAL4-VP16 transcription factor via a TEV protease site. The cells also express a beta-arrestin/TEV protease fusion protein and a beta-lactamase (BLA) reporter gene under the control of a UAS response element. Stimulation of the S1P4–R by agonist causes migration of the fusion protein to the GPCR, and through proteolysis liberates GAL4-VP16 from the receptor. The liberated VP16-GAL4 migrates to the nucleus, where it induces transcription of the BLA gene. BLA expression is monitored by measuring fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) of a cleavable, fluorogenic, cell-permeable BLA substrate. As designed, test compounds that act as S1P4–R agonists will activate S1P4–R and increase well FRET. Compounds were tested in triplicate at a final nominal concentration of 25 micromolar.

- 29.The regiochemistry and (2Z,5Z)-configuration of 24f were verified respectively by Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Coherence (HMBC) and 1H,1H-NOESY experiments performed on spectrometer Bruker DRX-600 equipped with a 5 mm DCH cryoprobe.In 1H,13C-HMBC spectrum the α-protons of the 2-(2-methoxyethyl)imino substituent only coupled to carbon C2 of the 3-methyl-2-((2-methoxyethyl)imino)thiazolidin-4-one scaffold. No NOE effects were observed between the α-protons of the 2-(2-methoxyethyl)imino and the 3-methyl substituent of the 3-methyl-2-(2-methoxyethyl)imino)thiazolidin-4-one core; the proton of the exocyclic olefinic bond at position 5 gave rise to a cross-peak only with the 2-methyl group of the pyrrol-3-yl ring (numeration as in Scheme 1).

- 30.The regiochemistry of 24g was verified by 1H,13C-HMBC experiment performed using spectrometer Bruker DRX-600 equipped with a 5 mm DCH cryoprobe: the α-protons of the 3-(2-methoxyethyl) substituent coupled to both carbons C2 and C4 of the 3-(2-methoxyethyl)-2-(methylimino)thiazolidin-4-one nucleus (numeration as in Scheme 1).