Abstract

In this column, Kimmelin Hull, community manager of Science & Sensibility, Lamaze International’s research blog, reprints and discusses a recent blog post series by acclaimed writer, lecturer, doula, and normal birth advocate Penny Simkin. Examined here is the fruitful dialog that ensued—including testimonies from blog readers about their own experiences with traumatic birth and subsequent posttraumatic stress disorder. Hull further highlights the impact traumatic birth has not only on the birthing woman but also on the labor team—including doulas and childbirth educators—and the implied need for debriefing processes for birth workers. Succinct tools for assessing a laboring woman’s experience of pain versus suffering are offered by Simkin, along with Hull’s added suggestions for application during the labor and birth process.

Keywords: childbirth, labor pain, posttraumatic stress disorder

INTRODUCTION BY KIMMELIN HULL

In February 2011, Penny Simkin ran a two-part series of blog posts on Science & Sensibility, Lamaze International’s research blog, discussing childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).1 Integral to this discussion is the issue of pain in childbirth—but the discussion does not end there. In this article, Simkin delineates the difference between pain and suffering and how to recognize when a traumatic birth experience potentiates the development of PTSD or its less severe cousin, posttraumatic stress effects (PTSE).

One underrecognized element of pain experienced during childbirth is the effect it has on individuals witnessing the laboring woman in pain. As health-care providers, we are trained to treat—if not completely obliterate—pain. We are taught that neglecting a person’s pain (the sixth vital sign) is tantamount to undertreatment of our patients—a form of medical negligence. When not otherwise trained, our human nature drives us to feel psychologically uncomfortable in the presence of another’s pain—even pain that is a part of a normal, rather than pathological, process. And yet maternity care providers, doulas, and birth partners are often ill equipped to witness a woman’s birth pain and to differentiate between pain and suffering. In the first of her two-part post series, Simkin addresses the issue of pain, suffering, and trauma in relation to birth.

Lamaze International has created a continuing education home study based on this article. Visit the Online Education Store at the Lamaze Web site (www.lamaze.org) for detailed instructions regarding completion and submission of this home study module for Lamaze contact hours.

PAIN, SUFFERING, AND TRAUMA IN LABOR AND SUBSEQUENT POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER: FIRST OF TWO POSTS BY PENNY SIMKIN2

After the health of mother and baby, labor pain is the greatest concern of women, their partners, and their caregivers. Nurses and doctors promise little or no pain when their medications are used, and they feel frustrated and disappointed if a woman has pain. Most are also extremely uncomfortable with her expressions of pain during labor—moans, crying, tension, frustration—because they don’t know how to help her, except to give her medication.

An enormous industry exists in North America to manufacture and safely deliver pain-relieving medications for labor. Hospital maternity departments are designed with elimination of pain as a primary consideration, complete with numerous interventions and protocols to keep the pain management medications from causing serious harm. When staff believes that labor pain equals suffering, they convey that belief to the woman and her partner, and, instead of offering support and guidance for comfort, they offer pain medication. If that is the only option, women will grasp for it.

Definitions of Pain and Suffering

If we check the definitions of “pain” and “suffering” in lay dictionaries, the two are often offered as synonyms of one another, which helps explain the fear of labor pain. It is a fear of suffering. But if we consult the scientific literature, there is a distinction among pain, suffering, and trauma. Pain has been defined as “an unpleasant sensory or emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” (Merskey, 1979, p. 250). The emphasis is on the physical origins of pain.

Lowe (2002) points out that “suffering” can be distinguished from pain, because by definition, suffering describes negative emotional reactions and includes any of the following factors: perceived threat to body and/or psyche, helplessness and loss of control, distress, inability to cope with the distressing situation, and fear of death of mother or baby. If we think about it, one can have pain without suffering and suffering without pain. We all can recall times when we have been in pain but did not fear damage or death to ourselves or others, nor did we feel unable to cope with the pain. For many people, athletic effort, recovery from planned surgery, dental work, and labor are painful, but these people do not suffer with them. This is because the person has enough modifiers (knowledge, attention to other matters or goals, companionship, reassurance, touch, self-help measures, feelings of safety, and other positive factors) to keep her from interpreting the painful experience as suffering. All pain is not suffering.

Lamaze International’s research blog, Science & Sensibility, is intended to help childbirth educators and other birth professionals gain the skills necessary to deconstruct the evidence related to current birth practices. Visit the Science & Sensibility Web site (www.scienceandsensibility.com) to stay up to date and comment on the latest evidence that supports natural, safe, and healthy birth practices.

By the same token, I’m sure we can recall times when we have suffered without pain. Acute worry or anguish about oneself or a loved one, death of a loved one, cruel or insensitive treatment, deep shame, extreme fear, loneliness, depression, and other negative emotions do not necessarily include real or potential physical damage but certainly cause suffering. Therefore, all suffering is not caused by pain. In fact, it is these negative modifiers that turn labor pain into suffering.

Of course, the goal of childbirth education has always been to reduce the negative modifiers and increase the positive ones. The goal of anesthesiology has been to remove awareness of pain, on the assumption that when there is little or no pain, there will be no suffering.

Suffering and Trauma

The American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) definition of trauma comes very close to the definition of suffering. Trauma involves experiencing or witnessing an event in which there is actual or perceived death or serious injury or threat to the physical integrity of self or others, and/or the person’s response included fear, helplessness, or horror (APA, 1994). Neither suffering nor trauma necessarily includes actual physical damage, although it may do so.

One’s perception of the event is what defines it as traumatic or not. As it pertains to childbirth, “Birth trauma is in the eye of the beholder” (Beck, 2004), and whether others would agree is irrelevant to the diagnosis.

One’s perception of the event is what defines it as traumatic or not. As it pertains to childbirth, “Birth trauma is in the eye of the beholder.”

Birth Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder After Childbirth

A traumatic birth includes suffering and may lead to PTSD, which, according to the APA (1994), means that the sufferer has at least three of the following symptoms that continue for at least 1 month:

-

•

nightmares

-

•

flashbacks

-

•

fears of recurrence

-

•

staying away from the people or location involved

-

•

avoiding circumstances in which it can happen again

-

•

amnesia

-

•

emotional numbing

-

•

panic attacks

-

•

emotional distress

In a national survey, 18% of almost 1,000 new mothers (up to 18 months after childbirth) reported traumatic births, as assessed by the PTSD Symptom Scale, a highly respected diagnostic tool. Half of these women (9% of the sample) had high enough scores to be diagnosed with PTSD after childbirth (Declercq, Sakala, Corry, & Applebaum, 2008).

Other smaller surveys (using women’s reports as the criteria for diagnosis) have found that between 25% and 33% of women report that their births were traumatic. Of these women, between 12% and 24% developed PTSD. In other words, between 3% and 9% of all women surveyed developed PTSD after childbirth (Adewuya, Ologun, & Ibigbami, 2006; Beck, 2004; Creedy, Shochet, & Horsfall, 2000; Czarnocka & Slade, 2000).

As we can see, every woman who has a traumatic birth does not go on to develop the full syndrome of PTSD. If they have fewer symptoms than the three or more required for the diagnosis, they may be described as having PTSE. Although disturbing, the women with PTSE are more likely to recover spontaneously over time than women with PTSD. The question of why some women develop PTSD and others do not is intriguing and multifactorial: The propensity to develop postbirth PTSD has to do with how women felt they were treated in labor, whether they felt in control, whether they panicked or felt angry during labor, whether they dissociated, and whether they suffered “mental defeat” (i.e., they gave up, feeling overwhelmed, hopeless, and as if they could not go on; Ayers, 2007; Czarnocka & Slade, 2000). Another risk factor for developing birth-related PTSD is having a history of unresolved physical, sexual, and/or emotional trauma from earlier in their lives. Even though unresolved previous trauma is unlikely to be healed during pregnancy, most of the other variables associated with PTSD can be prevented “through care in labor that enhances perceptions of control and support” (Czarnocka & Slade, 2000, p. 50).

PRACTICAL SUGGESTIONS TO PREVENT POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER AFTER CHILDBIRTH: SECOND OF TWO POSTS BY PENNY SIMKIN3

Based on the research findings on variables associated with traumatic birth and PTSD, as described earlier, I propose several steps that maternity care providers, expectant families, doulas, and childbirth educators can take to reduce a woman’s risk of birth-related PTSD. These steps include suggestions for before, during, and after birth. Perhaps by empowering partners and support team members with the tools to decrease a woman’s experience of suffering and trauma during birth, a decrease in “vicarious traumatization” (Ogletree, 2011b) might be realized as well.

Checklist for Before Labor

Identify the woman’s issues or fears relating to childbirth.

The caregiver should elicit a psychosocial and medical history from the woman, and if there is evidence of previous unresolved trauma, discuss and strategize a course of care that maximizes the woman’s feelings of being supported, listened to, and in control of what is done to her, and that minimizes the likelihood of loneliness, disrespect, and excessive pain (Alehagen, Wijma, Lundberg, & Wijma, 2005; Lukasse et al., 2010).

The unique nonclinical relationship between the doula and the client requires that doulas do not ask specific questions regarding the woman’s psychosocial and medical history but rather ask an open-ended question such as, “Do you have any issues, concerns, or fears that you’d like to tell me to help me provide better care for you?” The woman then has the option of whether or not to disclose sensitive issues. Many doulas, however, can recognize strong emotions without knowing specifics. The doula tries to be sensitive and accommodating without discussing her client’s anxiety directly.

Rather than asking class members about their issues, childbirth educators may find it more appropriate to discuss the potential effects of anxiety or old trauma on women’s experiences of labor and to provide resources such as books and referrals to support groups or counselors (possibly including the educator himself or herself, if he or she can provide counseling) that can be helpful. Caution: If offering his or her services for counseling, the educator may be perceived as having a conflict of interest in raising these issues. To avoid such conflict, I advise against charging a fee (beyond the class fee) for counseling one’s students, or to avoid mentioning himself or herself as a resource.

The purposes of counseling a pregnant woman with negative feelings about childbirth or maternity care are to help her clarify and address these feelings and strategize ways to (a) reduce their negative impact (at least), (b) prevent further suffering or retraumatization, and (c) even result in empowerment and healing for the woman (Simkin & Klaus, 2004). In fact, I feel that there’s a great need to increase the numbers of birth counselors—people with a deep knowledge of birth and its accompanying emotions; maternity care practices and local options; excellent communication skills; and an understanding of trauma, PTSD, and other mood disorders related to childbearing. Wise childbirth educators and doulas with good communication skills should consider expanding their roles in this direction, along with nurses and midwives who have the time and skills to provide such counseling.

Recommend that the woman/couple learn about labor and maternity care practices and master coping techniques for labor.

Childbirth classes that emphasize these elements, especially when they assist women and couples in personalizing their preferences and ways of coping with pain and stress, can take many surprises out of labor and empower parents to participate in their care and help themselves deal with pain and stress, whether with or without pain medications or other interventions (Escott, Slade, & Spiby, 2009).

Recommend a birth plan.

A birth plan is a document that describes the woman’s personal values, preferences, emotional needs, or anxieties regarding her child’s birth and her maternity care. A birth plan is most useful if it is the result of collaborative discussion between the woman and her caregiver, and if it is placed in the woman’s medical chart to be accessible for all who are involved in her care (Simkin, Whalley, Keppler, Durham, & Bolding, 2010). Usually, in hospitals where there is a spirit of cooperation and good will between clients and staff, birth plans are easily accommodated. Sometimes, as in some cases of previous trauma or other adverse events, a woman will have a greater need for special considerations than other women. If the effort is made with careful planning to address those needs, the potential for a safe, satisfying birth experience is great, without causing harm or overwork for the staff. For example, simple requests (e.g., having people knock and identify themselves before entering the woman’s room, limiting the number of routine vaginal exams to those that are necessary for a clinical decision, allowing departure from a routine such as forceful breath holding and straining for birth) require flexibility but are not dangerous. A woman is likely to feel respected and understood if the staff gives serious consideration to her requests. The birth plan should include her preferences for the use of pain medications, not only “yes” or “no” but also the degree of strength of her preferences (Simkin et al., 2010).

Obviously, in her birth plan (or another term instead of “plan” may be used), the woman should use polite and flexible language (couching her preferences in language such as “as long as the baby is okay,” or “if no medical problems are apparent”). She might prepare a Plan A for a smooth uncomplicated labor and a Plan B for unexpected twists that make intervention necessary. A birth plan allows everyone to be on the same page and ensures that the woman has a voice in her care, even when she is in the throes of labor. Childbirth educators and doulas have a responsibility to guide parents in the language and options included in the birth plan to maximize the likelihood that the plan will be well received while still reflecting the woman’s needs and wishes. If prenatal discussions indicate that the birth plan is unrealistic or unreasonable, there is an opportunity to discuss, clarify, and settle the problems before labor when it’s too late.

Checklist for During Labor

Provide care that contributes to a woman’s lifelong memory of a positive birth experience.

Individuals caring for laboring women should remind themselves that the birth experience is a long-term memory (Waldenström & Irestedt, 2006) that can be devastating, negative, depressing, acceptable, positive, empowering, ecstatic, or orgasmic. The difference between negative and positive memories of the birth experience depends not only on a healthy outcome but also on a process in which the woman was respected, nurtured, and aided.

Individuals caring for laboring women should remind themselves that the birth experience is a long-term memory that can be devastating, negative, depressing, acceptable, positive, empowering, ecstatic, or orgasmic.

In a study that I published years ago, on the long-term impact of a woman’s birth experience, I found that the most influential element in women’s satisfaction (high or low) with their birth experience, as recalled 15 to 20 years later, is how they remember being cared for by their clinical care providers (Simkin, 1991). In fact, it was that study that motivated me to do what I could to ensure that women receive the kind of care that will give them lifelong satisfaction with their birth experiences. The answer became the doula.

“How will she remember this?” is a question that everyone who is with a laboring woman should ask himself or herself periodically in labor, and then be guided by the answer to say or do things that will contribute to a positive memory.

The doula.

The research findings of the benefits of the doula are well known; in fact, a newly updated Cochrane Review of the benefits of doulas once again demonstrates the unique contribution of continuous support by a doula in improving numerous birth outcomes (Hodnett, Gates, Hofmeyr, Sakala, & Weston, 2011). In addition to the benefits reported in the Cochrane Review, I’d like to suggest a benefit that doulas may confer when traumatic birth is occurring: The doula’s care may be instrumental in preventing a traumatic birth from developing into PTSD. In their study on normal births, Czarnocka and Slade (2000) found that 24% of the women had PTSE, and 3% had the full syndrome of PTSD. They found that the women with PTSD were more likely to have felt unsupported and out of control than those who had PTSE. PTSE is far less serious that PTSD in terms of duration and spontaneous recovery.

For more information on Hodnett et al.’s (2011) Cochrane Review, “Continuous Support for Women During Childbirth,” read the Childbirth Connection’s press release (http://www.childbirthconnection.org/pdfs/continuous_support_release_2-11.pdf) and full review with a summary (http://www.childbirthconnection.org/laborsupportreview/).

Ironically, doulas are often traumatized by what they witness in birth settings where individualized care and low-intervention rates for normal birth are not emphasized or supported (Block, 2007). They feel frustrated, demoralized, or burned out, especially when their clients who had originally expressed a preference for minimal intervention seem oblivious to the departure from their stated preferences and even grateful to the doctor who “saved their baby” after unnecessary interventions (which the woman had not wanted in the first place) led to the need for cesarean surgery. The woman has a traumatic birth, but later seems okay with everything that happened and has only a few leftover trauma symptoms (PTSE). I feel certain that in some of these cases of PTSE, the doula, by remaining with the woman, nurturing and helping her endure the physical helplessness, the fear and worry for her baby and herself, may have provided the positive factors identified by Czarnocka and Slade (2000) that protected her from PTSD. Prevention of PTSD is a worthy goal for a doula when birth is traumatic (Simkin, 2008b).

Code word to prevent suffering.

No one wants a woman to suffer during labor. On the other hand, no supportive caregiver wants a woman to have pain medication that she had hoped to avoid. A previously agreed-upon “code word” provides a safety net for a woman who is highly motivated to have an unmedicated birth. She says her code word only when she feels that she cannot go on without medical pain relief. The code word frees the woman to complain, vocalize, cry, and even to ask for medications, but her support team knows to continue their pep talks and encourage her to continue and suggest some other coping techniques. However, if she says her code word, her team quits all efforts to help her continue without pain medications and turns to helping her get them (Simkin, 2008a).

Why is a code word better than continuing to help her cope without medications when a woman (who had felt strongly about avoiding them) says she cannot go on or vocalizes her pain loudly? It is because some women cope better if they can express their pain rather than having to act as if it does not hurt. A code word also guides the team much more clearly than the woman’s behavior. As one of my students told me when describing her loud vocalizations during labor, “I shouted the pain down!” It is really important for the nurse to know and understand the purpose of the code word, or she will feel the team is being cruel. The code word should be included in the woman’s birth plan. If a supporter wonders if the woman forgot her code word, he or she can remind the woman, “You have a code word, you know.” After I did this with a client who was crying and saying, “I can’t do this!” she decided to continue. She later told me that when I reminded her, she asked herself, “Am I suffering?” She decided she was not and went on to have a natural birth. She added, “I’m just an overdramatic person.”

Obviously, a code word is unnecessary if the woman plans to use an epidural.

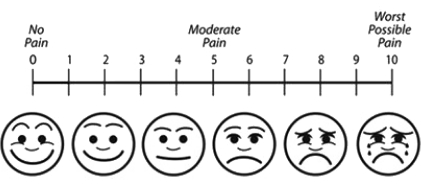

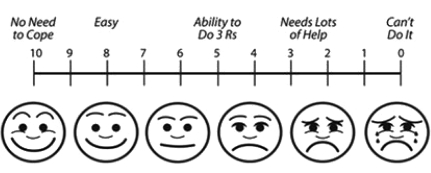

Pain rating scale and coping scale.

All hospitals use a Pain Intensity Scale to measure patients’ (including laboring women’s) pain. Figure 1 illustrates a version of the Pain Intensity Scale, similar to the scale used in most hospitals, to assess each patient’s (including laboring woman’s) pain. The goal, of course, is to ensure that no one suffers. The scale does not rate suffering, however, because pain and suffering are not the same, as explained in Part 1 of this blog post. Much more important is the woman’s ability to cope. Figure 2 illustrates the Pain Coping Scale, an adaptation of the Pain Intensity Scale that I developed to assess coping during labor and birth. If a woman rates her pain at 8 (very high) and her coping is also rated very high, she is not suffering. If pain is rated at 8 and coping is rated at 2, she could be suffering and obviously needs attention, assistance, and, very likely, pain medication.

Figure 1.

The Pain Intensity Scale: 0 to 10. Adapted from “Wong–Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale” in Clinical Handbook of Pediatric Nursing (2nd ed., p. 373), by D. Wong and L. Whaley, 1986, St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Company, for “Pain Medications for Labor & Birth” [PowerPoint slides], by P. Simkin, 2010, Waco, TX: Childbirth Graphics.

Figure 2.

The Pain Coping Scale: 10 to 0, developed to assess coping during labor and birth. Adapted from “Wong–Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale” in Clinical Handbook of Pediatric Nursing (2nd ed., p. 373), by D. Wong and L. Whaley, 1986, St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Company, for “Pain Medications for Labor & Birth” [PowerPoint slides], by P. Simkin, 2010, Waco, TX: Childbirth Graphics.

Assessing a woman’s coping is done differently than assessing her pain. Rather than asking her to rate her coping on a scale of 10 (coping most easily) to 0 (total inability to cope), the supporter observes her behavior for what I refer to as “the 3 Rs of coping with labor and birth”: relaxation (between, if not during, contractions); rhythm (in movements, breathing, moaning, and mental activity—counting breaths, song); and ritual (repeating the same rhythmic activity for many contractions in a row). If she does not maintain the 3 Rs, she might very well suffer and feel traumatized by her labor (Simkin, 2008a).

A second way to assess coping is to ask the woman, after a contraction, “What was going through your mind during that contraction?” If her answer focuses on positive, constructive thoughts or helpful activities, she is coping. If she focuses on how long or difficult the labor is, or how tired or discouraged she feels, or how much pain she feels, she is not coping well and may be suffering (Wuitchik, Bakal, & Lipshitz, 1989).

Intensive labor support may help a woman cope better and keep her from suffering, but pain medication may be the best way to relieve unmanageable pain that causes suffering. Help her obtain effective pain relief, whether it is pharmacological or nonpharmacological, according to her prior wishes and the present circumstances.

Provide continued support even when an epidural is used.

Caregivers must recognize that if a woman has an epidural, she still needs emotional support and assistance with measures to enhance labor progress and effective pushing. The absence of pain, usually accomplished so effectively by the epidural, does not mean absence of suffering. Nurses and caregivers in hospitals with high epidural rates are likely to make comments like, “There’s no need to suffer”; “You don’t have to be a martyr”; and “There’s nothing to prove here.” With this assumption that pain and suffering are the same, after the pain is eliminated, the woman’s emotional needs are often neglected. In their classic study of pain, coping, and distress in labor, with and without epidurals, Wuitchik, Bakal, and Lipshitz (1990) reported the following finding:

With epidurals, pain levels were reduced or eliminated. Despite having virtually no pain, these women also engaged in increased distress-related thought during active labor. The balance of coping and distress-related thought for women with epidurals was virtually identical to that of women with no analgesia. (p. 131)

What are women distressed about when they have no pain? Wuitchik and colleagues (1990) named many things (and I have added some that I have witnessed), including the length of labor, numbness, side effects such as itching and nausea, being left alone by supporters when the woman was “comfortable,” helplessness, passivity, worries over the baby’s well-being (especially with the sudden and dramatic reactions of staff when the mother’s blood pressure and fetal heart rates dropped), or feeling incompetent (when unable to push effectively despite loud directions to push long and hard).

The point is that women may suffer even if they have no pain, and their needs for continuing companionship, reassurance, kind treatment, assistance with position changes and pushing, and attention to their discomforts and their emotional state remain as important to the satisfaction and positive long-term memory of the woman with an epidural as they are to the unmedicated woman (Lally, Murtagh, Macphail, & Thomson, 2008).

Be aware of warning signs of birth trauma.

Take note if any variables occur during labor that are associated with traumatic births (listed and explained earlier). Warning signs of traumatic birth and potential PTSD include the following behaviors: feeling angry (blaming others); feeling alone, unsupported, helpless, overwhelmed, or out of control; panicking; dissociating; giving up; feeling hopeless and as if she cannot go on (“mental defeat”); and experiencing physical damage and a poor outcome. If a laboring woman exhibits some of these signs, her caregiver, doula, and others should do as much as possible to prevent the trauma from becoming PTSD later (remaining close to her; reassuring her when possible; helping her keep a rhythm through the tough times; explaining what is happening and why; holding her; making eye contact; and talking to her in a kind, firm, confident tone of voice, relieving her pain). The point is to help her maintain some sense that she is not totally alone, out of control, and overwhelmed.

Checklist for After the Birth

Seeds of accomplishment.

Before leaving the birth, a few specific, positive, and complimentary words from the “expert”—the woman’s doctor, midwife, or nurse—will remain in the woman’s mind as she ruminates on her traumatic birth. Caregivers can plant a seed of accomplishment in the woman’s mind by sharing constructive comments, such as the following: “I was so impressed when you said you wanted to try walking when the labor had stalled for so long”; or “. . . when you said you wanted to push a little longer”; or “. . . when you realized that we had to get the baby out right away, and you said, ‘Do whatever you have to do.’”

For additional articles, handouts, and references by Penny Simkin, visit her Web site (http://www.pennysimkin.com/articles.htm).

Anticipatory guidance for after birth.

When a woman’s labor and birth were traumatic, it is wise for the caregiver and her team to provide the following means of continued support and guidance:

-

1

Openly acknowledge the woman’s traumatic labor and birth experience: “You certainly did your part. I just wish it had gone more as you had hoped.”

-

2

Anticipate and address some ways she might feel later; for example, she may find herself thinking a lot about the birth and recalling her feelings at the time.

-

3

Give guidance on what to do: She can call her care provider, doula, childbirth educator, a good friend, or a counselor to review and debrief the experience (APA, 1994; Gamble et al., 2005; Gamble, Creedy, Webster, & Moyle, 2002; Hatfield & Robinson, 2002; Rowan, Bick, & Bastos, 2007). The process of debriefing cannot be rushed, and the counselor (caregiver, doula, or other) should be available when the woman is ready to discuss her traumatic birth experience.

-

4

Share resources that address traumatic birth experiences and may be helpful, such as books (e.g., Kendall-Tackett, 2009; Kitzinger, 2006; Madsen, 1994; Simkin and Klaus, 2004), articles (surf the Web!), and Internet support groups.

-

5

Believe the woman when she says her birth was traumatic, and accept her perceptions of the events before clarifying or correcting misinterpretations. Help her reframe the event more positively, if possible, or suggest therapeutic steps to recover from the trauma. If PTSD does result, a referral should be made to a traumatic birth support group or a trauma psychotherapist, preferably one with experience with maternal mental health issues.

In conclusion, this is a reminder that traumatic childbirth is all too common; but with personalized sensitive care, much birth trauma can be avoided. If birth is traumatic for the woman, steps can be taken before, during, and after childbirth to help ensure that the trauma does not become PTSD. In fact, processing a traumatic birth experience can even provide an opportunity to heal and thrive afterward.

Web Sites Offering Support Following Traumatic Birth Experiences.

-

•

The Birth Trauma Association

-

•

Solace for Mothers: Healing After Traumatic Childbirth

-

•

Trauma and Birth Stress—PTSD After Childbirth

CLOSING COMMENTARY BY KIMMELIN HULL

The idea of a traumatic childbirth experience turning into PTSD or PTSE greatly resonated with Science & Sensibility readers. Comments related to Simkin’s first blog post on PTSD began to stream in, full of personal birth stories and the postpartum mental health challenges that ensued. In fact, several respondents not only acknowledged their own struggles with birth-related PTSD, but also commented on its effects on birth-related care providers. For example, one reader, who is a doula, wrote:

Having suffered from my own PTSD as a result of traumatic births, I think it’s especially important for me to be reminded of where the pain comes from so that I’m clear whose birth I am actually attending. I do my best to empty my cup before working with a mama and allow her to have her own experience without the burden of my birth story brushing up against hers. (Ogletree, 2011a)

Most likely, a large percentage of childbirth educators and doulas have entered this profession in response to our own birth experiences—desiring to either guide other women through similarly empowering, normal, and healthy births or through a “better path” that we know and trust exists, as exemplified by this comment on Simkin’s blog post: “I became a doula, and am now a nursing student and a homebirth midwifery student BECAUSE of my own traumatic experience when having my son. I still suffer from PTSD because of it” (Stephanie, 2011).

Another respondent called for a separate blog post on “Vicarious Traumatization of the care team,” recognizing her own continued response to the difficult births she attends as a doula (Ogletree, 2011b). However, very little training in this arena exists today. Addressing our own personal experiences with birth is minimally discussed in the Lamaze Certified Childbirth Educator curriculum. Similarly, doulas with whom I have spoken often feel ill equipped when it comes to supporting women through extremely difficult births. In the medical field—particularly in high-stress settings such as emergency medicine—we have debriefing processes in place for all staff members involved in particularly traumatic cases. And yet, no such model exists for professionals who work in and around the childbirth arena.

Blog post respondents who were doulas agreed with Simkin’s emphasis on the importance of the doula’s role in helping women decrease their risk for PTSD. For example:

I discuss the difference between pain and suffering with my doula clients prenatally. Your presentation of this topic is concise and clear. . . . It is so valuable for someone who is at risk [for] PTSD, or even [experiencing] feelings of suffering in birth, to have good, knowledgeable support people at their side in birth. (Ferguson, 2011)

Several respondents recounted their own experiences in dealing with pain during labor. For example:

I’ve had four unmedicated births: two in hospital and two out-of-hospital with midwives. In my last labor, I suffered. I had good support from my husband, my midwife, and her assistant, yet the pain was overwhelmingly intense, quite different to my other labors. . . . I am not suffering from PTSD, yet I do find myself consumed with fear about my upcoming fifth delivery. (Becky, 2011)

In the second segment of her blog post series, Simkin introduces the technique of pairing the use of the Pain Intensity Scale with the Pain Coping Scale. In my clinical experience, some people have a difficult time rating their pain on a scale of 1 to 10. What constitutes a “10”? How little pain is consistent with a “1”? Not only is it difficult for some people to subjectively rate the intensity of their pain, but it is also difficult for maternity care providers and birth team members to objectively assess pain levels in a laboring woman. However, by combining the use of these assessment tools, we gain better insight as to when a woman’s experience of labor pain merges into suffering.

As perinatal mental health garners greater attention, issues such as childbirth-related PTSD will hopefully harness greater attention within the maternity care system. Acknowledging the lasting impact birth experiences can have on a woman and taking concerted steps to minimize practices that may be perceived as traumatic will greatly benefit not only the birthing woman but also the care providers and support persons who accompany her through birth. Summing up the gratitude for Simkin’s work in this arena, Tricia Pil (2011), a pediatrician and Science & Sensibility contributor, wrote:

Thank you so much, Penny, for your post raising awareness about postpartum PTSD, this sorely underrecognized, under- and misdiagnosed, and under- and mistreated condition. It is with sadness and chagrin that I admit that, even as a pediatrician, I had never even heard of postpartum PTSD—until it happened to me.

Penny Simkin’s original Science & Sensibility two-part blog posts on PTSD were published online on February 15, 2011, (http://www.scienceandsensibility.org/?p=2145) and on February 28, 2011 (http://www.scienceandsensibility.org/?p=2312). Simkin’s posts are reprinted here, with modifications for publication in The Journal of Perinatal Education and with additional commentary by Kimmelin Hull, community manager of the Science & Sensibility blog.

Originally posted by Penny Simkin on February 15, 2011, at http://www.scienceandsensibility.org/?p=2145

Originally posted by Penny Simkin on February 28, 2011, at http://www.scienceandsensibility.org/?p=2312

Biography

PENNY SIMKIN is a physical therapist who has specialized in childbirth education and labor support since 1968. Simkin is also the author of many books and articles on birth for parents and professionals, a cofounder of DONA International, and a member of the editorial staff of the journal, Birth. KIMMELIN HULL is a physician assistant, a Lamaze Certified Childbirth Educator, and the managing editor and chief writer for Lamaze International’s Science & Sensibility research blog. Hull teaches childbirth preparation and new-parenting classes in Bozeman, Montana, where she lives with her husband and three children.

REFERENCES

- Adewuya A. O., Ologun Y. A., & Ibigbami O. S. (2006). Post-traumatic stress disorder after childbirth in Nigerian women: Prevalence and risk factors. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 113(3), 284–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alehagen S., Wijma B., Lundberg U., & Wijma K. (2005). Fear, pain and stress hormones during childbirth. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 26(3), 153–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author [Google Scholar]

- Ayers S. (2007). Thoughts and emotions during traumatic birth: A qualitative study. Birth, 34(3), 253–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck C. T. (2004). Birth trauma: In the eye of the beholder. Nursing Research, 53(1), 28–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becky (2011, February16). Re: Pain, suffering, and trauma in labor and subsequent post-traumatic stress disorder: First of two posts by Penny Simkin, PT, CCE, CD(DONA) [Web log comment]. Retrieved from http://www.scienceandsensibility.org/?p=2145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Block J. (2007). Pushed: The painful truth about childbirth and modern maternity care. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press [Google Scholar]

- Creedy D. K., Shochet I. M., & Horsfall J. (2000). Childbirth and the development of acute trauma symptoms: Incidence and contributing factors. Birth, 27(2), 104–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarnocka J., & Slade P. (2000). Prevalence and predictors of post-traumatic stress symptoms following childbirth. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 39(Pt. 1), 35–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declercq E. R., Sakala C., Corry M. P., & Applebaum S. (2008, August). New mothers speak out: National survey results highlight women’s postpartum experiences. New York, NY: Childbirth Connection; Retrieved from http://www.childbirthconnection.org/pdfs/new-mothers-speak-out.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Escott D., Slade P., & Spiby H. (2009). Preparation for pain management during childbirth: The psychological aspects of coping strategy development in antenatal education. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(7), 617–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson M. (2011, February18). Re: Pain, suffering, and trauma in labor and subsequent post-traumatic stress disorder: First of two posts by Penny Simkin, PT, CCE, CD(DONA) [Web log message]. Retrieved from http://www.scienceandsensibility.org/?p=2145

- Gamble J., Creedy D., Moyle W., Webster J., McAllister M., & Dickson P. (2005). Effectiveness of a counseling intervention after a traumatic childbirth: A randomized controlled trial. Birth, 32(1), 11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble J. A., Creedy D. K., Webster J., & Moyle W. (2002). A review of the literature on debriefing or non-directive counseling to prevent postpartum emotional distress. Midwifery, 18(1), 72–79 doi: 10.1054/midw.2001.0287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield A., & Robinson E. (2002). The “debriefing” of clients following the birth of a baby. Practising Midwife, 5(5), 14–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodnett E. D., Gates S., Hofmeyr G. J., Sakala C., & Weston J. (2011). Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 2 Art. No.: CD003766. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall-Tackett K. A. (2009). Depression in new mothers: Causes, consequences, and treatment alternatives (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Haworth Press [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger S. (2006). Birth crisis. New York, NY: Routledge [Google Scholar]

- Lally J. E., Murtagh M. J., Macphail S., & Thomson R. (2008). More in hope than expectation: A systematic review of women’s expectations and experience of pain relief in labour. BMC Medicine, 6, 7 doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-6-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe N. K. (2002). The nature of labor pain. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 186(5 Suppl.), S16–S24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasse M., Vangen S., Øian P., Kumle M., Ryding E. L., & Schei B.; on behalf of the Bidens Study Group. (2010). Childhood abuse and fear of childbirth—A population-based study. Birth, 37(4), 267–274 doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00420.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen L. (1994). Rebounding from childbirth: Toward emotional recovery. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey [Google Scholar]

- Merskey H. (1979). Pain terms: A list with definitions and notes on usage. Recommended by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain, 6(3), 249–252 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogletree K. (2011a, February15, #3). Re: Pain, suffering, and trauma in labor and subsequent post-traumatic stress disorder: First of two posts by Penny Simkin, PT, CCE, CD(DONA) [Web log comment]. Retrieved from http://www.scienceandsensibility.org/?p=2145

- Ogletree K. (2011b, February15, #5). Re: Pain, suffering, and trauma in labor and subsequent post-traumatic stress disorder: First of two posts by Penny Simkin, PT, CCE, CD(DONA) [Web log comment]. Retrieved from http://www.scienceandsensibility.org/?p=2145

- Pil T. (2011, February15). Re: Pain, suffering, and trauma in labor and subsequent post-traumatic stress disorder: First of two posts by Penny Simkin, PT, CCE, CD(DONA) [Web log comment]. Retrieved from http://www.scienceandsensibility.org/?p=2145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rowan C., Bick D., & Bastos M. H. (2007). Postnatal debriefing interventions to prevent maternal mental health problems after birth: Exploring the gap between the evidence and UK policy and practice. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing / Sigma Theta Tau International, Honor Society of Nursing, 4(2), 97–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin P. (1991). Just another day in a woman’s life? Women’s long-term perceptions of their first birth experience. Part I. Birth, 18(4), 203–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin P. (2008a). The birth partner: A complete guide to childbirth for dads, doulas, and all other labor companions (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Harvard Common Press [Google Scholar]

- Simkin P. (2008b, September). Doulas under “friendly fire” from colleagues and birth activists. International Doula, 16(3), 26–28 [Google Scholar]

- Simkin P., & Klaus P. (2004). When survivors give birth: Understanding and healing effects of early sexual abuse for childbearing women. Seattle, WA: Classic Day Publishing [Google Scholar]

- Simkin P., Whalley J., Keppler A., Durham J., & Bolding A. (2010). Pregnancy, childbirth, and the newborn: The complete guide (4th ed.). Minnetonka, MN: Meadowbrook Press [Google Scholar]

- Stephanie (2011, February15). Re: Pain, suffering, and trauma in labor and subsequent post-traumatic stress disorder: First of two posts by Penny Simkin, PT, CCE, CD(DONA) [Web log comment]. Retrieved from http://www.scienceandsensibility.org/?p=2145

- Waldenström U., & Irestedt L. (2006). Obstetric pain relief and its association with remembrance of labor pain at two months and one year after birth. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 27(3), 147–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuitchik M., Bakal D., & Lipshitz J. (1989). The clinical significance of pain and cognitive activity in latent labor. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 73(1), 35–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuitchik M., Bakal D., & Lipshitz J. (1990). Relationships between pain, cognitive activity and epidural analgesia during labor. Pain, 41(2), 125–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]