Abstract

Several food borne outbreaks have highlighted the importance of Listeria monocytogenes to the public health and have been recognized as an emerging, important food borne pathogen, and a causative agent of listerioses. A number of genes are involved in the manifestation of Listeria virulence, hlyA is one among them. In the present study, 111 marine fish samples including prawns, finfishes and bivalves were screened for the presence of Listeria species. The isolates were characterized biochemically and further L. monocytogenes were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique using the hlyA gene as a tool to differentiate between L. monocytogenes and other non-pathogenic Listeria species. Out of 111 samples 5 (4.5%) samples were positive for L. monocytogenes. Among the three different types of samples bivalves were found to have maximum percent (12.5) of L. monocytogenes followed by prawns (3.84) and finfishes (2.9). Among all the 111 samples, 15 (13.51%) samples were positive for other Listeria species. It was observed that Listeria occurrence is more in shellfishes than in fin fishes. All the isolates were sensitive towards five different antibiotics in sequence ciprofloxacin > sulphafurazole > norfloxacin > ampicillin and gentamicin.

Keywords: Listeria monocytogenes, Isolation, Seafood, PCR, Hly A gene

Listeriosis is an important bacterial infection caused by a gram positive facultative anaerobe, non-spore-forming, rod-shaped bacteria, and intracellular pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. L. monocytogenes has been recognized as an important opportunistic human pathogen since 1929 and as a food borne pathogen since 1981. Its public health significance lies in its ubiquitous nature that is manifested in its host range, which includes 40 mammals, 20 birds, crustaceans, ticks and fishes [1]. Multiple key virulence factors, such as internalins (encoded by inlA and inlB), hemolysin (hlyA), phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC, plcA), phosphatidylicholin-specific phospholipase C (PC-PLC, plcB) and actin polymerization protein (actA) are important in L. monocytogenes pathogenesis [2]. Although L. monocytogenes is a non sporulating bacterium, it is resistant to different environmental conditions, including acid pH, high NaCl concentration, microaerophilia and refrigeration temperatures [3] with mortality rates on an average approaching 30%, L. monocytogenes far exceeds other common foodborne pathogens, such as Salmonella enteritidis [4, 5]. L. monocytogenes can be transferred to human beings mainly through food contaminated with this organism. Hazard analysis critical control point (HACCP) approach has been suggested to control Listeria in the food supply [6, 7]. Because of the high fatality associated with this organism, U.S. regulatory agencies have established a ‘zero tolerance’ for ready to eat foods.

Several reports indicate that fish and fishery products can be frequently contaminated with L. monocytogenes as this organism has been isolated from fish and fishery products from different parts of the world [8–11]. In India, a few studies have been conducted for the detection and confirmation of L.monocytogenes from sea foods mainly bivalves and finfishes. Especially in Goa region there are no published reports on L. monocytogenes studies in sea foods. Goa being coastal area fish consumption is more and sea food forms the main diet for Goans. Fish can act as a major vector of L. monocytogenes and other pathogenic microbes to the local people. This brings the need for the screening of L. monocytogenes in seafoods in order to prevent the food poisoning and also to prevent the economic loss for different food industries. The rapid and reliable detection of L. monocytogenes has been suggested to be ideally based on the detection of virulence markers of Listeria species by molecular techniques [12]. PCR is a technique which possesses rapidity, sensitivity, and specificity and could therefore be employed to facilitate rapid diagnosis of L. monocytogenes contamination. Thus, it is considered that DNA extraction and PCR detection could become a viable alternative to the conventional methods for detection of L. monocytogenes. The present investigation deals with the isolation and confirmation of L. monocytogenes from sea foods by rapid, reliable and simple PCR technique.

Standard cultures of L. monocytogenes (MTCC 1143), Staphylococcus aureus (MTCC 1144), Rhodococcus equi (MTCC 1135) were obtained from Microbial Type Culture Collection and Gene Bank (MTCC), Institute of Microbial Technology (IMTECH), Chandigarh, India. One hundred and eleven marine fish samples, bivalves (16), prawns (26) and finfishes (69) were collected from local fish markets of Goa, West coast of India. The samples were collected in UV sterilized polyethylene sachets at the places of collection, and processed immediately (within 5 h of collection) for microbial analysis.

Isolation of Listeria was attempted as per the USDA method described by McClain and Lee [13] after some modifications. Grey green colonies with black sunken centers on Polymixin Acriflavin Lithium chloride Ceftazidime Asculin Mannitol (PALCAM) agar, of about 0.5 mm diameter surrounded by a diffused black zone of aesculin hydrolysis after 24 h of incubation at 37 ± 1°C were considered to be of Listeria and were further treated for the Gram’s staining and motility test and also were subjected to biochemical tests i.e. methyl red, Voges–Proskauer (MR, VP), Rhamnose, Mannitol, Xylose and catalase test, Christie Atkins Munch Petersen (CAMP) test which is specific for Listeria species was performed with 5% sheep blood agar using the cultures of Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 1144 and Rhodococcus equi MTCC 1135. The Listeria isolates confirmed by above tests were further analysed by PCR [14] technique for the detection of L. monocytogenes.

Oligonucleotide primers used in the study were synthesized by Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO. The sequences of oligonucleotide primers used were 5′-GCA GTT GCA AGC GCT TGG AGT GAA-3′—Forward and 5′-GCA ACG TAT CCT CCA GAG TGA TCG-3′—Reverse for the hlyA gene.

DNA template for PCR was prepared by simple boiling and snaps chilling method [15]. Briefly, a loopful of cells grown overnight in BHI broth at 37°C. The obtained culture was centrifuged in a microfuge at 6000 rpm for 10 min. The recovered pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of sterilized DNAs and RNAs free milliQ water, followed by heating it in boiling water bath for 10 min and then snap chilling in crushed ice and used for the PCR reaction mixture.

The PCR was set for 50 μl reaction volume containing 5.0 μl of 10X PCR buffer (consisting of 100 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.3; 500 mM KCl; 15 mM MgCl2 and 0.01% gelatin), 0.2 mM dNTP mix, 2 mM MgCl2 and 10.1 μM of forward and reverse primer of each set, 1 unit of Taq DNA Polymerase, 5 μl of cell lysate and sterilized milliQ water to make up the reaction volume. The reaction was performed in Gradient Thermocycler (Thermohybaid, UK) with a preheated lid. PCR product (15 μl) after mixing with 2 μl bromophenol blue dye was analysed by gel electrophoresis by using 1.5% agarose gel containing 3 μl ethidium bromide. A reaction mix without DNA and one with 1 ng of L. monocytogenes MTCC 1143 total DNA were included as controls. All the isolates were also tested for antibiotics (ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, sulphafurazole, and gentamycin) sensitivity by standard disc diffusion method [16]. The results were interpreted as per the NCCLS criteria [17] (data not shown).

Out of 111 samples screened 23 samples showing black colonies with centered halo on PALCAM agar due to its ability of aesculin hydrolysis [18].

Out of these the 20 catalase positive isolates showed tumbling motility at 25 ± 1°C were subjected to biochemical and CAMP test (Table 1) as these two tests help to differentiate between the Listeria species. Listeria species utilize dextrose, esculin, and maltose, and some species utilize mannitol, rhamnose, and xylose with production of acid. An isolate utilizing mannitol with acid production is L. grayi. L. monocytogenes, L. ivanovii, and L. seeligeri produce hemolysis on sheep blood agar. Of the three, only L. monocytogenes fails to utilize xylose and is positive for rhamnose utilization. The difficulty in differentiating L. ivanovii from L. seeligeri can be resolved by the CAMP test. L. seeligeri shows enhanced hemolysis at the S. aureus streak. L. ivanovii shows enhanced hemolysis at the R. equi streak. Of the non-hemolytic species, L. innocua may provide the same rhamnose-xylose reactions as L. monocytogenes but it is negative for the CAMP test [18]. L. innocua sometimes gives negative results for utilization of rhamnose. A L. welshimeri isolate that is rhamnose-negative may be confused with a weakly hemolytic L. seeligeri isolate unless resolved by the CAMP test. Positive control (L. monocytogenes MTCC 1143) showed methyl red, Voges–Proskauer, rhamnose and catalase tests positive after 24 h incubation at 28 ± 1°C, whereas xylose, mannitol and nitrate tests were negative. Negative control was kept without the culture which did not show any change in the medium after 24 h also. Out of 20 catalase positive isolates 15 were showing same biochemical reactions as that of positive control and among these 15 isolates, 5 were showing the Christie Atkins Munch–Peterson (CAMP) test positive with S. aureus at 28 ± 1°C after 24 h incubation. Isolates which were showing positive CAMP test towards the S. aureus MTCC 1144 strain with intense β haemolysis and negative CAMP test with R. equi MTCC 1135 were considered to be L. monocytogenes. L. seeligeri is also CAMP-positive to the S. aureus strain and CAMP-negative to R. equi. All the 5 CAMP positive cultures were subjected to PCR test for the confirmation of L. monocytogenes using hlyA gene as target. The hlyA gene codes for listeriolysin, a thiol activated cytolysin which is essential for the release of the organism after initial phagocytosis and after actin-mediated transport to neighbouring cells [19] and one of the virulence factors for pathogenesis.

Table 1.

Biochemical and CAMP test for the presumed (23) isolates

| Sr. no. | Fish samples | MR | VP | Nitrate | Rhamnose | Xylose | Mannitol | Catalase | Gram character | Motility | CAMP | Morphology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rostreliger Kanaguret | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | Cocci |

| 2 | Gerrus oblongus | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | Cocco bacilli |

| 3 | Caranx melampygus | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | Rods |

| 4 | Caranx Melampygus | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | Rods |

| 5 | Etroplus suratensis | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | Cocci |

| 6 | Opisthopterus tartoor | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | Rods |

| 7 | Gerrus oblongus | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | Cocci |

| 8 | Engraulis hamiltonii | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | Cocci |

| 9 | Cynoglossus macrolepidotus | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | Rods |

| 10 | Sunetta species | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | Rods |

| 11 | Meretrix meretrix | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | Rods |

| 12 | Caranx boops | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | Cocci |

| 13 | Equula dussumieri | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | Cocci |

| 14 | Mercenaria species | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | Rods |

| 15 | Engraulis commersonianus | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | Rods |

| 16 | Fenneropenaeus indicus | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | Cocco bacilli |

| 17 | Gerrus lucids | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | Rods |

| 18 | Engraulis hamiltonii | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | Cocci |

| 19 | Vellorita cyprinoids | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | Rods |

| 20 | Gerruas oblongus | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | Rods |

| 21 | Sunetta species | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | Cocci |

| 22 | Vellorita cyprinoids | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | Rods |

| 23 | Penaeus indicus | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | Cocco bacilli |

| 24 | Positive control L. monocytogenes MTCC 1143 | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | Rods |

| 25 | Negative control (blank) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | Cocci |

VP Voges–Proskauer test, CAMP Christie Atkins Munch–Peterson test, + positive test, − negative test, MR methyl red test

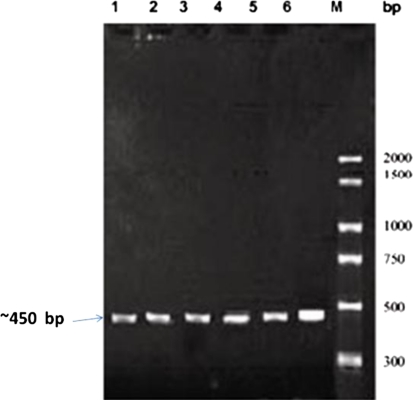

Based on all the above tests performed, we found the 18.01% occurrence of Listeria. Maximum numbers of Listeria isolates were found in bivalves followed by finfishes and prawns. Out of 20 Listeria isolates 5 (4.5%) isolates were confirmed as L. monocytogene since they showed the presence of hlyA gene when subjected to PCR assay represented by a single band of ~450 bp (Fig. 1) similar to that of positive control. Regarding primer specificity a primer that involve targeted gene hlyA was selected.

Fig. 1.

PCR profile of the isolates showing hlyA (~450 bp) virulence associated gene of L. monocytogenes.Lane M PCR marker (300 bp to 2000 bp), Lane 1L. monocytogenes MTCC1143, Lanes2–6 isolates from the samples

The highest incidence of L. monocytogenes was recorded from bivalves followed by finfishes and prawns (Table 2). All other Listeria isolates were found to be negative for hlyA gene. In present study the percentage occurrence of L. monocytogenes is less than that reported by Jayasekaran et al. [20], as 12.1% in fresh shell fishes and 17.2% in fresh finfishes where as it is higher than the 3% occurrence in European fish [21]. Compared to fresh water fishes [20] (13%), there is low L. monocytogenes occurrence in marine finfishes (2.9%). Also the prevalence is more in tropical region than temperate [20, 22]. Bivalve molluscs showed high occurrence of L. monocytogenes (12.5%) among all three varieties of samples and compared to (7.5%) findings of Simon et al. [10]. Since bivalves are filter feeders they can accumulate more microorganisms than fishes, from waters impacted by sewage pollution etc. Compared to the 3.84% occurrence of L. monocytogenes in prawns, earlier studies [23] shows 44% frequency of L. monocytogenes in raw samples and 22% in ready to eat prawns. Overall occurrence of L. monocytogenes in present study was higher than the values reported in the fish squid and bivalve mollusks samples in San, Luis Argentina [24]. The antibiotic sensitivity of all the Listeria isolates towards five antibiotic discs was in the sequence ciprofloxacin > sulphafurazole > norfloxacin > ampicillin and gentamicin.

Table 2.

Isolation of Listeria species from seafood

| Samples | Samples tested no. | Listeria spp. | L. monocytogenes | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | % | ||

| Bivalves | 16 | 2 (12.5) | 2 (12.5) | 25 |

| Prawns | 26 | 2 (7.69) | 1 (3.84) | 11.53 |

| Finfishes | 69 | 11 (15.94) | 2 (2.9) | 18.84 |

| Overall | 111 | 15 (13.51) | 5 (4.5) | 18.01 |

Isolation of L. monocytogenes and other Listeria spp. from the raw seafood indicates the potential public health hazard. Diligent enforcement of sanitary conditions of food contact surface and handling areas, and personal hygiene practices should reduce the potential contamination of fishery products by L. monocytogenes at the retails level. Earlier studies show the low occurrence of L. monocytogenes in fresh water fishes than in marine water [20, 25]. Since the climatic conditions were also different for some studies, study should be conducted in the same region in order to check the variation in occurrence of this organism both in fresh and marine fishes. The PCR method used in the present study can be used for the rapid identification of the L. monocytogenes, as the traditional practice of biochemical tests can be time consuming and sometimes confusing within the species.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Director, ICAR Research Complex for Goa, Ela, Old Goa for providing necessary facilities.

References

- 1.Sonnenwirth AC. Listeria monocytogenes. In: Sonnenwirth AC, Jarret L, editors. Gradwohls clinical laboratory methods and diagnosis. London: CV Mosby co; 1980. pp. 1673–1692. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rocourt L, Jacquet Ch, Reilly A. Epidemiology of human listeriosis and seafoods. Int J Food Microbiol. 2000;62:197–209. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00336-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Recur J, Bille J. Food borne listeriosis. Wls Health Stat Quart. 1997;50:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu D, Ainsworth AJ, Austin FW, Lawrence ML. Characterization of virulent and avirulent Listeria monocytogenes strains by PCR amplification of putative transcriptional regulator and internalin genes. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52:1066–1070. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05358-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roche SM, Gracieux P, Albert I, Gouali M, Jacquet C, Martin PM, Velge P. Experimental validation of low virulence in field strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3429–3436. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3429-3436.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huss HH. Development and use of the HACCP concept in fish processing. Int J Food Microbiol. 1992;15:33–44. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(92)90133-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huss HH. Globalization of fish products and processing standards: a microbiologist’s point of view. Bull Aquac Assoc Can. 1994;94:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karunasagar I, Karunasagar I. Listeria in tropical fish and fishery products. Int J Food Microbiol. 2000;62:177–181. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura H, Hatanaka M, Ochi K, Nagao M, Ogasawara J, Hase A, Kitase T, Haruki K, Nishikawa Y. Listeria monocytogenes isolated from cold-smoked fish products in Osaka City, Japan. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;94:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon M, Tarrago C, Ferrer MD. Incidence of Listeria monocytogenes in fresh foods in Barcelona (Spain) Int J Food Microbiol. 1992;16:153–156. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(92)90008-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coillie E, Werbrouck H, Heyndrickx M, Herman L, Rijpens N. Prevalence and typing of Listeria monocytogenes in ready to eat food products on Belgian market. J Food Prot. 2004;67:2480–2487. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-67.11.2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalpana K, Mitra S, Muriam PM (2004) Subtyping of Listeria monocytogenes by Multilocus Sequence Typing. Animal science research report. Oklahoma State University Publication no. 1008

- 13.McClain D, Lee WH. Development of USDA-FSIS method for isolation of Listeria monocytogenes from raw meat and poultry. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1998;71:660–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Notermans SH, Dufrenne J, Leimeister-Wachter M, Domann E, Chakraborty T. Phosphatidylinositol specific phospholipase C activity as a marker to distinguish between pathogenic and nonpathogenic Listeria species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:2666–2670. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.9.2666-2670.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shakuntala I, Malik SVS, Barbuddhe SB, Rawool DB. Isolation of Listeria monocytogenes from buffaloes with reproductive disorders and its confirmation by polymerase chain reaction. Int J Food Microbiol. 2006;117:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bauer AW, Kirby WM, Sherris JC. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standard single disc method. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;45:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests. Approved standard. NCCLS document M2–A5. Wayne: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hitchins AD (2003) Bacteriological analytical manual chapter 10, detection and enumeration of Listeria monocytogens in foods (Online) available from United States Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/food/scienceResearch/LaboratoryMethods/Bacteriological Analytical Manual BAM/ucm071400.htm

- 19.Vines A, Swaminathan B. Nucleotide sequence analysis of two virulence associated genes in Listeria monocytogenes serotype 1/2b and comparison with the same genes in other serotypes important in human disease. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1997;24:166–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.1997.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jayasekaran G, Karunasagar I, Karunasagaar I. Incidence of Listeria species in tropical fish. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996;31:333–340. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(96)00980-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies AR, Capell C, Jehanno D, Nychas GJE, Kirby RM. Incidence of foodborne pathogens on European fishes. Food Control. 2001;12:67–71. doi: 10.1016/S0956-7135(00)00022-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Embarek PKB. Presence, detection and growth of Listeria monocytogenes in seafoods: a review. Int J Food Microbiol. 1994;23:17–34. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)90219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arumugaswamy RK, Rahamat Ali GR, Siti Nadzriah BAH. Prevalence of Listeria monoctogenes in foods in Malaysia. Int J Food Microbiol. 1994;23:117–121. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)90227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laciar AL, Centorbi ONP. Listeria species in seafood: isolation and characterization of Listeria spp. from seafood in San Luis, Argentina. Food Microbiol. 2002;19:645–651. doi: 10.1006/fmic.2002.0454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jallewar PK, Kalorey DR, Kurkure NV, Pande VV, Barbuddhe SB. Genotypic characterization of Listeria isolated from fresh water fish. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;114:120–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]