Abstract

We report the production of two types of siderophores namely catecholate and hydroxamate in modified succinic acid medium (SM) from Alcaligenes faecalis. Two fractions of siderophores were purified on amberlite XAD, major fraction was hydroxamate type having a λmax at 224 nm and minor fraction appeared as catecholate with a λmax of 264 nm. The recovery yield obtained from major and minor fractions was 297 and 50 mg ml−1 respectively. The IEF pattern of XAD-4 purified siderophore suggested the pI value of 6.5. Cross feeding studies revealed that A. faecalis accepts heterologous as well as self (hydroxamate) siderophore in both free and iron complexed forms however; the rate of siderophore uptake was more in case of siderophores complexed to iron. Siderophore iron uptake studies indicated the differences between hydroxamate siderophore of A. faecalis and Alc E, a siderophore of Alcaligenes eutrophus.

Keywords: Siderophores, IEF, Crossfeeding, Iron uptake

Introduction

Siderophores are iron-scavenging ligands synthesized under low iron stress for the solubilization and transport of iron (Fe III) inside the microbial cell [1]. Siderophore producing PGPR have been widely used for plant growth promotion in various crops [2–5] and for the biocontrol of phytopathogenic fungi [6–9].

They exhibit requisite; hydrophilic, lipophilic and hydro-lipo-phile properties for chelating the extracellular iron respectively from aqueous environment, through the lipoprotenaceous membrane receptors of the cell and from fatty environment [7].

Till to date hundreds of different siderophores have been characterized and all of them contain either of hydroxamate (C=O, N-(OH) and catecholate (derivates of 2,3 dihydroxy benzoic acid) groups [1]. Great variation occurs in physico-chemical properties of siderophores, one organism may produce a variety of siderophores therefore for the extraction of different siderophores different recovery methods and identification approaches have been used [10, 11]. Iso-electric-focussing (IEF) is emerging as a promising tool for the identification of siderophore based on the diversity in the structure of peptide molecules of siderophores [9, 12, 13]. This diversity confers the strict specificity of recognition usually observed between a given strain and its siderophore [14, 15].

Some PGPR possess the multiple receptors or share the identical receptor recognition site and can utilize siderophores produced by other microbes (heterologous siderophores) [16–18]. Utilization of heterologous siderophores by PGPR offer them added advantage of growth under iron limiting conditions in presence of large number of competing microorganisms and it determines the persistence of PGPR in soil [11].

In earlier studies [6, 7] we reported potent antifungal activity of A. faecalis, considering this biofungicidal potential of organism, the present work was aimed towards chemical characterization of siderophore and ability of organism to utilize heterologous siderophores.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Culture and Screening for Siderophore Production

From local rhizospheric soil of banana plant of research farm of North Maharashtra University, Jalgaon, a bacterium was isolated. The culture was screened for siderophore production by Chrome Azurol Sulphonate (CAS) agar method [19] and Universal Chemical Assay [20].

Biochemical Characterization and Identification of Isolate

For the partial identification, isolate was subjected to various biochemical tests (Table 1) as mentioned in Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology [21]. This partially identified culture was subjected to confirmation on the basis of BIOLOG-GN microtitre plate analysis for which the organism was grown on Biological Universal Growth Medium (BUGM) (Biolog Inc., California, USA) plates at 28 ± 2°C for 24 h and observed for the ability of isolate to oxidize 95 different carbon sources as given in Table 2.

Table 1.

Biochemical characteristics of isolate

| Characteristics | Observation | Characteristics | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram reaction | Gram negative rods | PHB accumulation | Accumulated |

| Motility | Motile | Carbon source utilized | Acetate, propionate succinate and citrate |

| Catalase reaction | Positive | Oxidase reaction | Positive |

| DNAase | Negative | Amylase | Positive |

| Isolated from | Soil | Growth in nutrient broth MacConkey’s broth |

Luxuriant and fruity odor Luxuriant |

Table 2.

Biolog breath print showing oxidation of different carbon sources by A. feacalis

| Substrate | Results |

|---|---|

| α-Cyclodextrin | − |

| Dextrin | − |

| Glycogen | − |

| Tween 40 | ± |

| Tween 80 | ± |

| N-Acetyl-d-galactosamine | − |

| N-Acetyl-d-glaucosamine | − |

| Adonitol | − |

| l-Arabinose | − |

| α-Lactose | − |

| Lactulose | − |

| Maltose | − |

| d-Mannitol | − |

| d-Mannose | − |

| d-Melibiose | − |

| β-Methylglucoside | − |

| Psicose | − |

| d-Raffinose | − |

| l-Rhamnose | − |

| d-Trehalose | − |

| Turanose | − |

| Xylitol | − |

| Methylpyruvate | + |

| Acetic acid | ± |

| Cis-aconitic acid | ± |

| Citric acid | + |

| Formic acid | + |

| d-Galacotinic acid lactone | − |

| α-Ketovaleric acid | ± |

| d,l-Lactic acid | − |

| Malonic acid | − |

| Propionic acid | + |

| Quinic acid | − |

| d-Saccharic acid | + |

| Sebacic acid | − |

| Succinic acid | + |

| Bromosuccinic acid | ± |

| d-Sorbitol | − |

| l-Alanine | ± |

| l-Alanyl-glycine | − |

| l-Asparagine | ± |

| l-Aspartic acid | − |

| l-Glutamic acid | + |

| Glycyl-l-aspartic acid | − |

| Glycyl-l-glutamic acid | − |

| l-Histidine | − |

| Hydroxyl-l-proline | − |

| l-Leucine | + |

| l-Phenylalanine | + |

| l-Proline | + |

| l-Pyroglutamic acid | + |

| d-Serine | − |

| l-Serine | − |

| l-Threonine | − |

| Phenylethylamine | − |

| Succinamic acid | − |

| Sucrose | − |

| d-Arabitol | − |

| Cellobiose | − |

| i-Erythol | − |

| d-Fructose | − |

| d-Fucose | − |

| d-Galactose | − |

| Gentibiose | − |

| α-d-Glucose | − |

| m-Inositol | − |

| Glucoranamide | − |

| Putresceine | − |

| 2-Aminoethanol | − |

| 2,3-Butanediol | − |

| Glycerol | − |

| d,l-α-Glycerophosphate | − |

| Glucose-1-phosphate | − |

| Inosine | + |

| d-Galactorinic acid | − |

| d-Gluconic acid | − |

| d-Glucosamanic acid | − |

| d-Glucoronic acid | − |

| β-Hydroxybutyric acid | + |

| γ-Hydroxybutyric acid | − |

| Itaconic acid | − |

| α-Ketobutyric acid | ± |

| α-Ketoglutaric acid | − |

| Glucose-6-phosphate | + |

| Thymidine | − |

| Uridine | − |

| d,l-Carnitine | − |

| γ-Aminobutyric acid | − |

| Urocanic acid | − |

| Aalaninamide | + |

+ Positive, − negative, ± variable

Siderophore Production, Detection and Estimation

Siderophore production was carried out by submerged process at two levels namely shake flask and bioreactor level. A. faecalis (6 × 107 cells ml−1) was inoculated in succinic acid medium consisting of gl−1 K2HPO4: 6, KH2PO4: 3, MgSO4·7H2O: 0.2, NH4SO4: 1, succinic acid: 4 [17], incubated at 28 ± 2°C with constant shaking at 120 rpm for 24 h. Followed by centrifugation (15 min 4000×g) and subjecting cell free supernatant to CAS assay for the detection of siderophores [19]. For determining the hydroxamate and catecholate nature of siderophores, Csaky [22] and Arnow tests [23] were performed respectively.

Recovery of Siderophore

CAS positive cell free supernatant was concentrated (10×) on rotary vacuum evaporator (Buchi, R-124, Switzerland) at 40°C at 100 rpm, pH of the concentrated supernatant was set to 6.0 with 12 N HCl and it was loaded on XAD [10, 24]. CAS positive fractions obtained from the columns were evaporated to dryness.

Iso-Electric Focusing (IEF) of Siderophores

The method of Koedam et al. [25] was adapted to the Mini–IEF cell, model 111 (Bio-Rad, USA). Casting of the gels (125 by 65 by 0.4 mm) made of 5% polyacrylamide with 2% Bio-Lyte 3-10 ampholines was done. About 20 μl of tenfold concentrated and lyophilized hydroxamate siderophore of A. faecalis sample along with various standard siderophores were deposited in the wells made on gel. IEF was performed at 100 V for 15 min, at 200 V for 15 min and at 450 V for 1 min at 4°C. Electrophoresed gel was visualized under UV light at 563 nm to locate the bands and their iso-electric pH (pI). pI were determined by comparing with standard known purified siderophores.

Cross Feeding Studies

Nutrient agar plates supplemented with EDTA [1 mg ml−1] [NAEDTA] previously refrigerated for 24 h for the chelation of contaminating iron by EDTA were used. A. faecalis was plated on NAEDTA plates containing different siderophores (10 μl each impregnated on sterile filter paper disc) viz. PAO II, Quinolobactin, Desferrioxamine-B, Aerobactin, Azotobactin, Desferriciprogen, Schizobactin, Rhizobactin, Enterobactin, coprogen, desferribrubin, ferrichrysin, salicylic acid, desferriferrichrome and siderophores of Enterobacter cloacae, and Chryseobacterium indologenes. Plates were kept for diffusion at 4°C for 30 min followed by incubation at 29°C for 24 h and results were recorded as no growth (−), slight growth (+) and good growth (+++, usually >10 mm).

Siderophore-Iron Uptake Studies

For checking the capacity of A. faecalis to synthesize uptake system and to uptake the iron chelate complexed to self siderophores and Alc E (a siderophore produced by A. eutrophus), a 24 h old biomass of A. faecalis obtained after centrifugation of SM, was re-suspended at an optical density of 0.33 at 600 nm in SM. Label mixture consisting of 5 μl 59Fe3+ solution (FeCl3 in 0.1 M HCl, specific activity 110–925 MBq/mg of iron) was diluted with distilled water and then mixed with 10 μl of a 4 mg ml−1 of XAD purified hydroxamate siderophore of A. faecalis, another label mixture consisted of Alc E, after 30 min. of incubation at 28 ± 2°C, the final volume of both label mix was adjusted to 1 ml with incubation medium. Bacterial suspension (1.8 ml) was mixed at time zero with 0.2 ml of label mix. After 20 min of incubation in water bath at 25°C, 1 ml of bacterial suspension was filtered through Whatman nitrocellulose filter paper (0.45 μm porosity) each filter was washed twice with 2 ml of fresh incubation medium and wrapped in aluminum foil [26]. Kinetic uptake measurements were performed by measuring the radioactivity on a Gamma 4000 counter (Beckman, Palo, Alto, California) [26].

Results and Discussion

Screening for Siderophore Production

After 24 h incubation at room temperature, change in color of CAS agar from blue to orange red confirmed the ability of organism to produce and excrete siderophores.

Biochemical Characterization and Identification of Isolate

In the microscopic study of 24 h old culture of isolate, Gram negative, motile, non-spore forming rods of 0.8 × 1.5–2 μm were observed. The isolate capable of producing different enzymes like amylase, oxidase and catalase but not DNAase and coagulase, and growing luxuriantly in nutrient, MacConkey’s and enrichment broth in the temperature range of 27–37°C and at wide pH range (6.5–8.5). After 18 h growth in nutrient broth, uniform turbidity and pleasant fruity odor with the formation of yellow colored pigment resembled very well with the characteristics of A. faecalis as mentioned in Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology [21] (Table 1). Microtitre plate analysis revealed the ability of isolate to oxidize number of carbon sources (Table 2). The metabolic (oxidation) pattern of these carbon sources when compared with corresponding database; it yielded a very good identification of the isolate as Alcaligenes faecalis with similarity index [SI] value of 0.784.

Siderophore Production, Detection and Estimation

Siderophore production was carried out at two levels namely shake flask and bioreactor level. In the shake flask studies change in the color of SM from colorless to golden yellow and an instant change in the color of CAS reagent from blue to orange red after the addition of cell free supernatant revealed the presence of siderophores in SM.

Recovery of Siderophore

From XAD column two CAS positive fractions were obtained with a λmax at 224 (major fraction) and 264 nm (minor fraction). Major fraction was found to contain hydroxamate type while minor fraction contained catecholate type of siderophore. It is known that hydroxamate type siderophores are comparatively stable, strong iron chelators and possesses antifungal activity [13]. Siderophore yield obtained from these fractions was 297 and 50 respectively mg l−1.

Iso-Electric Focusing (IEF) of Siderophore

IEF pattern of siderophore sample revealed an iso-electric point in acidic range with a pI value of 6.5 which is similar to that of Alcaligin E a siderophore produced by Alcaligenes eutrophus [27].

Cross Feeding Studies

Cross feeding studies revealed that A. faecalis is capable of utilizing PAO II, Quinolobactin, Desferrioxamine-B, Aerobactin, Azotobactin, Desferriciprogen, Schizobactin, Rhizobactin, Enterobactin, coprogen, desferribrubin, ferrichrysin, salicylic acid, desferriferrichrome A and the siderophores produced by Chryseobacterium indologenes, Enterobacter cloacae and self hydroxamate siderophore (Table 3). Although the rate of iron uptake differ from siderophore to siderophore, it seems that A. faecalis can utilize wide range of heterologous siderophore as a source of iron. This indicated the potential of organism to utilize heterologous siderophores during iron competition in the environment [28] which is expected to increase the competitive and survival potential of the organism under natural environment.

Table 3.

Cross feeding studies—uptake of various siderophores by A. faecalis

| Source | Siderophore | Zone of A. faecalis growth (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | PAO II | 15 |

| Quinolobactin | 11 | |

| Streptomyces viridosporus | Desferrioxamine-B | 11 |

| Erwinia carotovora | Aerobactin | 15 |

| Rhizobium meliloti | Azotobactin | 14 |

| Desferriciprogen | 16 | |

| Schizobactin | 16 | |

| Rhizobium meliloti | Rhizobactin | 13 |

| E. coli | Enterobactin | 16 |

| Curvularia lunata | Coprogen | 13 |

| Rhizobium meliloti | Desferribrubin | 15 |

| Ferrichrysin | 14 | |

| Salicylic acid | 13 | |

| Desferrichrome A | 12 | |

| Chryseobacterium indologenes | Catecholate | 15 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | Hydroxamate | 15 |

| A. faecalis | Hydroxamate | 20 |

Siderophore-Iron Uptake Studies

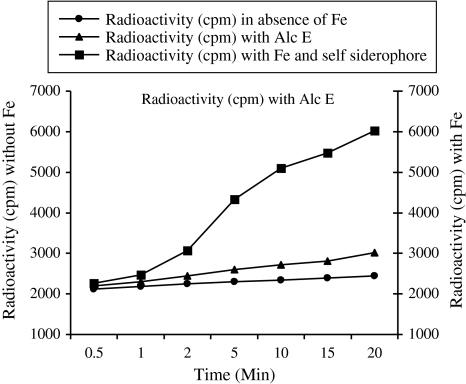

During iron uptake study (59Fe3+) it was found that A. faecalis accepted the iron, which was indicated by increase in radioactivity (growth) (Fig. 1) of the sample when compared with control (without Fe). The rate of uptake of iron complexed siderophore was increasing with increase in incubation time, optimum (6026 cpm) being at 20 min. Uptake values for label-mix with XAD purified hydroxamate siderophore of A. faecalis were in increasing order stating from 2261 at 5 min incubation time and 6026 at the end of 20 min incubation. Label-mix with Alc E showed only small increase in radioactivity. This indicated that A. faecalis was not able to utilize Alc E and that suggesting that although these two siderophores have similar pI but their uptake is different which may be because of the differences in receptor systems and differences in their chemical structure, because if two siderophores bear chemical resemblance they are taken up by same receptor system.

Fig. 1.

Radioactivity of A. feacalis cells incubated with and without iron (59Fe3+)

Conclusion

A. faecalis possesses the competitive potential of survival during iron competition in the environment. Although the pI values of siderophore of A. faecalis and Alc E were similar, inability of A. faecalis to uptake Alc E indicated that these two siderophores differ from each other.

Acknowledgments

Financial assistance to the corresponding author from BRNS, DAE, Government of India, New Delhi is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Sayyed RZ, Badgujar MD, Sonwane HM, Mhaske MM, Chincholkar SB. Production of microbial iron chelators (siderophores) by fluorescent pseudomonads. Ind J Biotechnol. 2005;4:486–490. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sayyed RZ, Naphade BS, Chincholkar SB. Ecologically competent rhizobacteria for plant growth promotion and disease management. In: Rai MK, Thakare PV, Chikhale NJ, Wadegaonkar PA, Ramteke AP, editors. Recent trends in biotechnology. Jodhpur: Scientific Publisher; 2005. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sayyed RZ, Naphade BS, Joshi SA, Gangurde NS, Bhamare HM, Chincholkar SB. Consortium of A. faecalis and P. fluorescens promoted the growth of Arachis hypogea (Groundnut) Asian J Microbiol Biotech Environ Sci. 2009;11(1):83–86. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sayyed RZ, Patel PR, Patel DC. Plant growth promoting potential of P solubilizing Pseudomonas sp occurring in acidic soil of Jalgaon. Asian J Microbiol Biotech Environ Sci. 2007;9(4):925–928. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sayyed RZ, Naphade BS, Chincholkar SB. Siderophore producing Alcaligenes faecalis promoted the growth of medicinal plants. J Med Aromat Plant Sci. 2007;29:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sayyed RZ, Chincholkar SB. Siderophore producing A. faecalis more biocontrol potential vis-avis chemical fungicide. Curr Microbiol. 2009;58(1):47–51. doi: 10.1007/s00284-008-9264-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sayyed RZ, Patil AS, Gangurde NS, Joshi SA, Fulpagare UG, Bhamare HM. Siderophore producing A. faecalis: a potent fungicide for sustainable biocontrol of groundnut phytopathogens. Res J Biotechnol. 2008;3:411–414. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stintzi A, Mayer JM (1994) Search for siderophores in microorganisms. In: Manja KR, Shankaran R (ed) Microbes for better living. MICON 94 proceedings of AMI conference, CFTRI, Mysore, India

- 9.Kintu K, Dave BP, Dube HC. Detection and chemical characterization of siderophores produced by certain fungi. Ind J Microbiol. 2001;41:87–91. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budzikiewicz W. Secondary metabolites from fluorescent pseudomonads. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;204:209–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb05868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plessner O, Klapatch T, Guerinot ML. Siderophore utilization by Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1688–1690. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1688-1690.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazzola M. Mechanism of natural soil suppressiveness to soil borne diseases. Anton Leeuw. 2002;81:557–564. doi: 10.1023/A:1020557523557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer JM, Stintzi A, Poole K. The ferripyoverdine receptor of Pseudomonasaeruginosa PAOI recognizes the ferripyoverdines of Pseudomonasaeruginosa PAOI and Pseudomonasfluorescens ATCC 13525. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;170:145–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerinot ML. Microbial iron transport. Ann Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:742–743. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.003523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page WJ (1993) Growth conditions the demonstration of siderophores and iron-repressible outer membrane proteins in soil bacteria with an emphasis on free-living soil diazotrophs. In: Barton LL, Heming BC (ed) Iron chelation in plants and soil microorganisms, San Diego, pp 75–109

- 16.Koster M, Ovaa W, Bitter W, Weisbeck PJ. Multiple outer membrane receptors for uptake of ferric pseudobactin in Pseudomonas putida WCS358. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;248:735–743. doi: 10.1007/BF02191714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer JM, Abdallah MA. The Fluorescent pigments of Fluorescent pseudomonas: biosynthesis, purification and physicochemical properties. J Gen Microbiol. 1978;107:319–328. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer JM, Goeffroy VA, Baida N, Gardan L, Izard D, Limanceau P, Achouak W, Pellorini NJ. Siderotyping typing a powerful tool for the identification of fluorescent and nonfluorescent pseudomonads. Appl Env Microbiol. 2002;68:2745–2753. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.6.2745-2753.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milagres AMF, Machuca A, Napoleao D. Detection of siderophore production from several fungi and bacteria by a modification of chrome Azurol S (CAS) agar plate assay. J Microbiol Methods. 1999;37:1–6. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(99)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwyn R, Neilands JB. Universal chemical assay for detection and determination of siderophores. Anal Biochem. 1987;160:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kersters K, Ley J. Genuc Alcaligenes. In: Krieg NR, Holt JG, editors. Bergy’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Baltimore: William and Wilkins; 1984. pp. 361–373. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Csaky TZ. An estimation of bound hydroxylamine in biological materials. Acta Chem Scand. 1948;2:450–454. doi: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.02-0450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnow LE. Colorimetric determination of the components of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine tyrosine mixtures. J Biol Chem. 1937;118:531–537. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sayyed RZ, Chincholkar SB. Purification of siderophores of Alcaligenes faecalis on Amberlite XAD. Bioresour Technol. 2006;97:1026–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koedam N, Witttouk E, Gaballa A, Gills A, Hofte M, Cornelis P. Detection and differentiation of microbial siderophores by isoelectric focusing and Chrome Azurol S agar overlay. Biometals. 1994;7:287–291. doi: 10.1007/BF00144123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munsch P, Geoffroy V, Altassova T, Mayer JM. Application of siderotyping for characterization of Pseudomonas tolaasii and Pseudomonas reactans, isolates associated with brown blotch disease of cultivated mushrooms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:4834–4841. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.11.4834-4841.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fusch RM, Schaffer M, Goffery V, Meyer JM. Siderotyping—a powerful tool for the characterization of pyoverdine. Curr Top Med Chem. 2001;1:31–35. doi: 10.2174/1568026013395542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crowley DE, Reid CPP, Szaniszlo PJ. Modeling of iron availability in the plant rhizosphere. In: Manthey JA, Crowely DE, Luster DG, editors. Biochemistry of metal micronutrient in the rhizosphere. Boca Raton: CRC press Inc; 1987. pp. 401–425. [Google Scholar]