Abstract

Thirty-one Tocklai vegetative (TV) tea clones contained caffeine and total catechin 44.39 and 227.55 mg/g dry weight of leaves, respectively. The (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) was the most abundant (109.60 mg/g) followed by -(−)-epigallocatechin (EGC, 44.54 mg/g), (−)-epicatechin gallate (ECG, 41.74 mg/g), (−)-epicatechin (EC, 27.42 mg/g) and +catechin (4.25 mg/g). Total catechins were highest in TV 20 (509.7 mg/g) and lowest in TV 6 (71.7 mg/g). The tea clones that contain high level of total catechin exhibited the strongest antimicrobial activity. Among caffeine and flavanol compounds, theaflavins (TF) present in black tea possess a similar antimicrobial potency as EC present in fresh leaves, and that the conversion of catechins to TF during fermentation in making black tea tends to alter their antimicrobial activities. The bioactive molecules other than catechins present in tea leaves may also contribute towards antimicrobial activity.

Keywords: Antimicrobial activity, Catechins, Tea extract, TV tea clones

Introduction

The search for components with antimicrobial activity has gained increasing importance in recent years due to growing worldwide concern about the alarming increase in the rate of infection by antibiotic-resistant microorganisms. For a long period of time, plants have been a valuable source of natural products for maintaining human health, especially in the last decade, with more intensive studies for natural therapies. Higher green plants (Spermatophyta), gymnosperms and angiosperms alike, are able to produce structurally unique secondary metabolites (alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, etc.) exhibiting antimicrobial and/or antitumor/antiviral activities, covering close to 12,000 antibiotic compounds [1]. In the widest sense, all the plant secondary metabolites with biological activity may also be considered as antibiotics [1].

Camellia sinensis (L) O. Kuntze, the most distinguished member of the family Theaceae as a beverage has been consumed worldwide. Tea has been a plant of interest from the prehistoric days and there is a growing awareness during the past few years about its medicinal values attributed to some of the phenolic compounds present in the leaves of this plant used for the manufacture of tea. There are four main catechins found in tea leaves, including (−)-epicatechin (EC), 3-(−)-epigallocatechin (EGC), (−)-epicatechin gallate (ECG) and (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and may be present at concentrations of up to 1 mg/ml in a cup of tea [2]. Catechins account for 6–16% of the dry green tea leaves [3] and EGCG is the major catechin in tea leaves [4]. The catechin content in tea leaves varies with season. The average catechin content in tea leaves was 22.0, 20.1, 19.4 and 19.2% in summer, spring, fall, and winter, respectively [5]. Theaflavins (TF) are another group of polyphenol pigments found in both black and oolong tea. TF are formed from polymerization of catechins at the fermentation or semifermentation stage during the manufacture of black or oolong tea [6]. Both catechins and TF have recently received much attention as protective agents against cardiovascular disease and cancer [7]. Numerous pharmaceutical experiments on human, animal, and in vitro studies suggest that tea may have various types of beneficial biological activities, including antioxidant [8], anticarcinogenic [9], anti-inflammatory [10], inhibition of tooth decay [11], reduction of blood pressure [12], controlling obesity [13] and antimicrobial properties [14].

Since 1949, 31 Tocklai vegetative (TV) tea clones have been developed at Tocklai Experimental Station, Jorhat, Assam, India, for commercial cultivation. This investigation deals with the screening of in vitro antimicrobial activities in the leaf extracts of 31 TV tea clones and to identify the principal bioactive components (catechins) in the tea extracts.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Extract Preparation

Fresh mature leaves of 31 TV tea clones were collected in April, 2008, from the germplasm preservation plots of Tocklai Experimental Station, Jorhat, Assam, India. The tea clones were grown under similar agro-climatic conditions without shade. Tea leaves were dried in open air at room temperature, 20 g of leaves were finely ground in a homogenizer, and extracted overnight with 100 ml methanol shaking gently. The extracts were filtered through filter paper, dried in a rotary evaporator at 40°C, and again extracted with ethyl acetate and evaporated to dryness. Dry, brown coloured crude extract of most of the tea clones were found to be water soluble, weighed and dissolved in sterile water to 5 mg/ml, and sterilized by passing through a 0.45-μm cellulose acetate membrane. DMSO 2% was used to dissolve the extracts in the culture media when necessary. All extracts were maintained in amber glass vials at −20°C.

Total TF from black tea were extracted according to Mahanta [15]. Extracted TF spectral data were compared with authentic samples.

Microorganisms and Chemicals

The test strains Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 737, Bacillus subtilis MTCC 441, Proteus vulgaris MTCC 426, Escherichia coli MTCC 443, Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 741, Candida albicans MTCC 227 and Aspergillus niger MTCC 282 used for screening antimicrobial activities were procured from Microbial Type Culture Collection and Gene Bank (IMTECH, Chandigarh, India). All the bacterial strains were maintained at −20°C in containing 15% (v/v) glycerol. Before testing, the suspensions were transferred to nutrient broth and cultivated overnight at 37°C (bacteria) and potato dextrose broth (fungi and yeast) at 25 and 28°C.

Chemicals used for this study (caffeine, gallic acid, ECG, EC, EGCG, and +catechins) were procured from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Nutrient, potato-dextrose and Czapeks-Dox media for antimicrobial tests were purchased from Hi-Media Lab. (Mumbai, India).

In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity and MIC of the Extract

For in vitro screening of antimicrobial activity, the crude extract of each tea clone, sterilized by filtration, and used for assaying antimicrobial activity by agar well diffusion method against test microorganisms [16]. The inoculum (100 μl) containing 1 × 104 colony-forming units (CFU) of each microbial strain were used and 100 μl of crude extract (500 μg) of each tea clone were dispensed into agar cup. Pure caffeine and catechins were also tested in the same way at 100 μg/agar cup. Standard antibiotic discs were used as positive controls. The diameters of inhibition zones were recorded after 24 h of incubation at 37°C for bacteria, 28°C for C. albicans and after 48 h at 25°C for A.niger. Each experiment was repeated thrice and inhibition zones were calculated.

The extracts of TV clones that showed highest total catechins/antimicrobial activity was tested by agar dilution method to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) against S. aureus and P. aeroginosa according to NCCLS [17]. Ampicillin was used as the standard to compare the antimicrobial activity (MIC) of the extracts. The microbes were grown in nutrient broth, and the overnight culture was spot-inoculated on the nutrient agar plates such that the inoculum contained 2 × 106 CFU. The plates were incubated at 37°C, examined after 24 h and incubated further for 72 h, wherever necessary. The MIC determination was performed in triplicate, and the experiment was repeated wherever necessary.

Analysis of Caffeine and Catechins by HPLC

The solvent extract of tea leaves were analyzed for catechins and caffeine, and quantitatively estimated by HPLC with Luna 5μ phenyl-hexyl-phenomenax column (4.5 × 250 mm) and UV–Visible detector at 278 nm. The solvent system used was solvent “A” (2.0% acetic acid and 9.0% acetic acetonitrile); solvent “B” (80% acetonitrile) as described in ISO (ISO committee draft, 1999). The chromatographic peaks were identified and estimated by comparing the retention times and areas of the standard catechins expressed as mg/g dry weight of tea leaves.

Results and Discussion

Antimicrobial Spectrum of the Extracts

The complete list and types of the 31 TV tea clones tested in this work is shown in Table 1. All the TV clones showed antibacterial activity against at least one of the test organisms except tea clone TV 6. Among the microorganisms tested S. aureus and P. aeroginosa were most susceptible to the inhibitory effect of TV clone extracts (500 μg crude extract/agar cup), whereas Klebsiellapneumoniae was least sensitive. E. coli and B.subtilis were inhibited to a similar extent (data not shown). On the other hand, C. albicans MTCC 227 and A. niger MTCC 282 were resistant to fresh tea leaf extracts tested (data not shown). Okubo et al. [18] had also reported that Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Trichophyton rubrum were inhibited by tea, but not C. albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans.

Table 1.

Caffeine and catechins content in solvent extracts of matured leaves of TV tea clones (values are in mg/g dry weight of tea leaves)

| TV clone | Caffeine | Catechins | Total catechin | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGC | +C | EC | EGCG | ECG | |||

| TV1 (AC hybrid) | 26.00 | 23.8 | 9.1 | 25.6 | 211.9 | 116.0 | 386.4 |

| TV2 (A) | 11.00 | 21.5 | 2.2 | 8.9 | 91.1 | 43.9 | 167.6 |

| TV3 (A) | 9.00 | 37.7 | 2.6 | 14.1 | 96.1 | 33.9 | 184.4 |

| TV4 (A) | 13.00 | 21.4 | 3.8 | 13.9 | 54.6 | 24.3 | 118.0 |

| TV5 (A) | 9.00 | 21.2 | 4.7 | 13.8 | 60.1 | 20.7 | 120.5 |

| TV6 (A) | 12.00 | 5.6 | 2.4 | 14.4 | 34.8 | 14.5 | 71.7 |

| TV7 (Ch. hyb) | 40.00 | 11.5 | 6.5 | 17.5 | 254.5 | 40.6 | 330.6 |

| TV8 (A) | 14.00 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 15.3 | 53.0 | 23.8 | 103.1 |

| TV9 (Cam) | 23.00 | 30.4 | 4.2 | 12.8 | 88.8 | 27.6 | 163.8 |

| TV10 (A) | 46.00 | 57.6 | 4.0 | 35.2 | 245.3 | 80.6 | 422.7 |

| TV11 (A) | 27.00 | 93.9 | 4.7 | 44.6 | 225.1 | 73.1 | 441.4 |

| TV12 (A) | 13.00 | 26.8 | 4.6 | 17.1 | 77.5 | 28.0 | 154.0 |

| TV13 (A) | 39.00 | 24.8 | 4.0 | 20.3 | 106.6 | 41.7 | 197.4 |

| TV14 (Ass. hyb) | 30.00 | 49.1 | 4.9 | 40.4 | 116.8 | 70.7 | 281.9 |

| TV15 (A) | 41.00 | 80.6 | 5.8 | 51.2 | 101.4 | 60.3 | 299.3 |

| TV16 (Ass. hyb) | 38.00 | 49.0 | 2.7 | 23.8 | 155.1 | 5.5 | 236.1 |

| TV17 (Ass. hyb) | 19.00 | 47.0 | 4.6 | 36.4 | 41.2 | 37.9 | 167.1 |

| TV18 (Cam) | 75.00 | 83.0 | 4.0 | 24.4 | 144.0 | 42.1 | 297.5 |

| TV19 (Cam) | 68.00 | 47.2 | 3.0 | 30.8 | 137.0 | 79.4 | 297.4 |

| TV20 (Cam) | 54.00 | 142.8 | 3.2 | 55.7 | 229.5 | 78.5 | 509.7 |

| TV21 (A) | 73.00 | 54.8 | 4.9 | 48.3 | 88.0 | 20.9 | 216.9 |

| TV22 (Cam) | 132.00 | 48.0 | 4.3 | 31.6 | 71.7 | 35.3 | 190.9 |

| TV23 (Cam) | 64.00 | 29.7 | 4.8 | 24.3 | 60.2 | 30.4 | 149.4 |

| TV24 (Cam/spp. hyb) | 50.00 | 61.1 | 4.5 | 30.9 | 148.1 | 35.8 | 280.4 |

| TV25 (Cam) | 62.00 | 55.5 | 7.1 | 44.3 | 101.3 | 44.6 | 252.8 |

| TV26 (Cam) | 65.00 | 51.6 | 1.6 | 16.0 | 86.2 | 23.9 | 179.3 |

| TV27 (Cam) | 65.00 | 45.9 | 2.4 | 14.2 | 48.3 | 14.7 | 125.5 |

| TV28 (Cam) | 101.00 | 27.6 | 3.3 | 34.0 | 46.1 | 60.7 | 171.7 |

| TV29 (Cam,Triploid) | 64.00 | 76.8 | 3.2 | 36.2 | 108.2 | 40.5 | 264.9 |

| TV30 (Cam) | 40.00 | 19.9 | 4.8 | 27.2 | 62.9 | 30.1 | 144.9 |

| TV31 (AC-Cam hyb) | 53.00 | 29.3 | 4.6 | 26.7 | 52.1 | 14.0 | 126.7 |

| Mean ± SE | 44.39 ± 5.18 | 44.54 ± 5.20 | 4.25 ± 0.28 | 27.42 ± 2.29 | 109.60 ± 11.47 | 41.74 ± 4.46 | 227.55 ± 19.27 |

The analysis was done by HPLC

AC hybrid Assam × China, A Assam, Ass. hyb Assam hybrid, Cam Cambod, Cam/spp. hyb Cambod/species hybrid, Ch. hyb China hybrid and AC-Cam hyb Assam China-Cambod hybrid

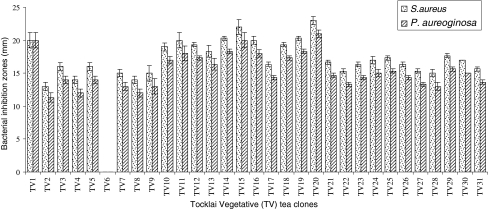

Variations in bioactivities shown by the TV tea clone extracts against S. aureus and P. aeroginosa are shown in Fig. 1. It was confirmed that all the extracts have interesting antimicrobial activities. In vitro screening of some of the TV clone extracts viz. 1, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19 and 20 showed higher antibacterial activities (≥20 mm inhibition zones against S. aureus and ≥17 mm zone against P. aureginosa) than the other TV clones (Fig. 1). The extracts of Cambod clone TV 20 exhibited highest zone of inhibition against S. aureus and P. aeroginosa (Fig. 1). The MIC of solvent extracts of TV 20 against S. aureus and P. aeroginosa were 190 and 220 μg crude extract/ml, respectively. The MIC of the standard ampicillin against S. aureus and P. aeroginosa were 0.50 and 32.0 μg/ml, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Antibacterial activity of TV tea clone leaf extracts against S. aureus and P. aeroginosa. Antimicrobial activity was assayed following agar cup diffusion method. 500 μg Crude extract of each tea clone were dispensed into agar cups. Data are expressed as means ± SE, n = 3. The significance of differences in inhibition zones shown by TV clones was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) by Students’ t test. The significance level for all analysis was P = 0.05. CD at 0.05 = 1.76, 1.84, for S. aureus and P. aeroginasa respectively

The average caffeine and total catechin in solvent extracts of TV clones were 44.39 and 227.55 mg/g, respectively (Table 1). EGCG was the most abundant (109.60 mg/g) followed by EGC (44.54 mg/g), ECG (41.74 mg/g), EC (27.42 mg/g) and +Catechin (4.25 mg/g). The amount of total catechins registered high values in TV 20 (509.7 mg/ml) and lowest by 71.7 mg/g in TV 6 (Table 1). The level of total catechins, EGCG and ECG of tea clone TV 6 solvent extract was much lower than the other TV clones and it may not be sufficient to inhibit test organisms (Table 1). Although the Assam variety of tea plants registered high values in most of the catechins forms, the catechin index was highest in the extracts of TV 20 (Cambod type) followed by Assam type clone TV 11, TV 10 and TV 1 (Table 1). Most of the tea clone extracts containing high total catechins exhibited strong antimicrobial activities (Table 1; Fig. 1). Therefore, the decreased antimicrobial activity of the extracts as shown in Table 1 may be attributed to the least amount of catechins in these TV tea clones. All the TV clones developed by Tocklai Experimental station were by selection and conventional breeding between selected parents of three varieties (Assam, China and Cambod). A few clones are either Assam-China hybrid or China hybrid. All the TV clones are diploid (2n = 30) except TV 29 (triploid, 2n = 45) and combine all the qualities of tea as a beverage. Among these tea clones, TV 20 (Cambod) extract exerted strong antimicrobial activity with highest catechin content (Table 1; Fig. 1). Though some of the Cambod clone solvent extracts (TV 22, 23, 24, 25 and TV 26) showed promising antimicrobial activity in vitro; their parental combinations are different from TV 20. It is generally considered that Cambod variety is not preferred for quality, but used as the yield clone. From the experimental data, it appears that these clones are equally important as Assam or China type in terms of medicinal value.

Some tea clone extracts (TV 7 and TV 10) contained higher EGCG content (254 and 245 mg/g, respectively) than the extracts of TV 20 (229 mg/g), but with less antimicrobial activity than TV 20 (Table 1; Fig. 1). This may be due to some bioactive molecule present in tea leaves other than catechins or synergistic effect of individual catechins in the extracts. El-Gammal and Mansour [19] reported that the flavonols quercitin, kaempferol, and myricetin exhibited activity against gram-positive bacteria and Quercitin had MIC of 37 μg/ml for S. aureus and was not active against E. coli. Also more than 300 volatile flavour components have been reported in black tea [20], and more than 100 such components have been reported in green tea and found some of these to be microbiologically active [21]. Some combinations of catechins with antibiotics also exhibit synergistic activities and/or are effective against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. EGCG is an excellent candidate because the extensive research has revealed that β-lactams and EGCG have synergic effects against multidrug-resistant bacteria [22]. EGCG synergizes the activity of β-lactams against MRSA because both EGCG and β-lactams directly or indirectly attack the same target: peptidoglycan synthesis [22]. Theasinensin A, a decomposition product of EGCG, reduced antibiotic resistance of methicillin-resistant S. aureus [23].

Antimicrobial Activity of Individual Catechin

Growth inhibition zones of commercial tea phytochemicals and standard antibiotics against S. aureus and P. aeroginosa are shown in Table 2. The bacterial strain S. aureus was inhibited by all the eight standard antibiotics tested and P. aeruginosa was sensitive to chloramphenicol, erythromycin and gentamicin (Table 2). Tea catechins EGCG, ECG, EGC, gallic acid and TF showed inhibition of both the test organisms. Several studies have suggested that the purified catechin fractions from green and black tea, and ECG and EGCG in particular, inhibit the growth of many bacterial species [14, 21, 24]. We found that little information exists concerning the relative antibacterial activity among individual catechins gallic acid and TF. The present observations suggested that the antibacterial activity was in decreasing order (EGCG > ECG > EC ≥ TF ≥ gallic acid > EGC) against S. aureus and P. aeroginosa as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Antibacterial activities of tea caffeine and flavanols

| Inhibition zone (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | P. aeroginosa | |

| Compound (100 μg/agar cup) | ||

| Caffeine | NIa | NI |

| Gallic acid | 15 (±1.15)b | 13 (±0.577) |

| EGC | 10 (±1.15) | 8 (±0.577) |

| (+)-Catechin | NI | NI |

| EC | 15 (±0.33) | NI |

| EGCG | 26 (±1.15) | 23 (±0.577) |

| ECG | 22 (±0.58) | 20 (±0.577) |

| Theophylline | NI | NI |

| TF | 15 (±0.33) | 15 (±0.577) |

| Standard antibiotic (concentration μg/disc) | ||

| Ampicillin (10) | 17 (±0.33) | NI |

| Cephalothin (30) | 32 (±0.577) | NI |

| Chloramphenicol (2) | 20 (±0.577) | 25 (±0.33) |

| Clindamycin (15) | 25 (±0.33) | NI |

| Erythromycin (15) | 30 (±0.33) | 15 (±0.58) |

| Gentamicin (10) | 20 (±1.15) | 30 (±0.33) |

| Oxacillin (1) | 30 (±0.33) | NI |

| Vancomycin (30) | 12 (±0.33) | NI |

The antibacterial activities have been determined by agar well diffusion assay

aNo inhibition

bMean ± SE

Ikigai et al. [24] had also reported that EC was much less active than EGCG [24]. S. aureus was more susceptible than gram-negative E. coli, consistent with a much greater binding of EGCG to Staphylococci. Higher levels (MIC = 800 μg/ml) were needed to inhibit gram-negative bacteria (E. coli, K. pneumoniae, S. typhi, P. mirabilis, P. aeruginosa, and S. marcescens) than MIC of 50–100 μg/ml of EGCG against several strains of Staphylococci (S. aureus, S. epidermis, S. hominis, and S. haemolyticus) [25]. The structure of the cell wall as well as the variable affinities of ECGC to cell wall components (peptidoglycans) may govern susceptibilities of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria to EGCG. The EGCG-induced damage of the cell wall and interference with its biosynthesis through direct binding with peptidoglycan are the major reasons for the susceptibility of Staphylococcus to EGCG [26]. Detailed physicochemical studies suggested that the bactericidal activities of galloylated tea catechins at the cell membrane level might be due to their specific perturbations of the ordered structure of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine present in bacterial cell wall membranes [27]. Fukai et al. [28] reported that the activities of the TF were similar to those of the simple catechins. TF are the products formed when catechins are oxidized and dimerized. The antibacterial activity of TF was similar to that of EC but it was lower than that of ECG and EGCG (Table 2).

Conclusions

The antimicrobial activity of tea leaves could be correlated with the catechin content, which is dependent on the choice of planting material and clonal variation. The antimicrobial activity shown by fresh tea leaf extracts is mainly due to the catechins EGCG and ECG. Other components may also play a role in the antimicrobial synergy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Director, Tocklai Experimental Station, TRA, Assam, India, for providing necessary facilities for this work. The authors gratefully acknowledge the In-charge, Statistical Department, TES, TRA, for carrying the statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Berdy J. Bioactive microbial metabolites: a personal view. J Antibiot. 2005;58:1–26. doi: 10.1038/ja.2005.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakanaka S, Kim M, Taniguchi M, Yamamoto T. Antibacterial substances in Japanese green tea extract against Streptococcus mutans, a cariogenic bacterium. Agric Biol Chem. 1989;53:2307–2311. doi: 10.1271/bbb1961.53.2307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu QY, Chen ZY. Isolation and analysis of green tea polyphenols by HPLC. Anal Lab. 1999;18:70–72. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirk RE, Othmer DF. Encyclopedia of chemical technology. 3. New York: Wiley; 1980. pp. 628–648. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kan N. Formation of aroma during the manufacture of black tea. Sci Agric. 1980;28:338–342. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Subramanian N, Venkatesh P, Ganguli S, Sinkar VP, Subramanian N, Venkatesh P, Ganguli S, Sinkar VP. Role of polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase in the generation of black tea theaflavins. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:2571–2578. doi: 10.1021/jf981042y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buschman JL. Green tea and cancer in humans: a review of the literature. Nutr Cancer. 1998;31:51–57. doi: 10.1080/01635589809514697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ichihashi M, Ahmed NU, Budiyanto A, et al. Preventive effect of antioxidant on ultraviolet-induced skin cancer in mice. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;23:45–50. doi: 10.1016/S0923-1811(00)00083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nihal A, Hasan M. Green tea polyphenols and cancer: biological mechanisms and practical implications. Nutr Rev. 1999;57:78–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1999.tb06927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katiyar SK, Matsui MS, Elmets CA, Mukhtar H. Polyphenolic antioxidant (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate from green tea reduces UVB-induced inflammatory responses and infiltration of leukocytes in human skin. Photochem Photobiol. 1999;69:148–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeo SG, Ahn CW, Lee YW, Yeo SG, Ahn CW, Lee YW, Lee TG, Park YH, Kim SB. Antioxidative effect of tea extracts from green tea, oolong tea and black tea. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 1995;24:229–304. [Google Scholar]

- 12.An BJ. Chemical structure and isolated of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor from the Korean green tea. Life Resour Ind. 1998;2:67–80. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dulloo AG, Duret C, Rohrer D, et al. Efficacy of a green tea extract rich in catechin polyphenols and caffeine in increasing 24-h energy expenditure and fat oxidation in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:1040–1045. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.6.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou CC, Lin LL, Chung KT. Antimicrobial activity of tea as affected by the degree of fermentation and manufacturing season. Int J Food Microbiol. 1999;48:125–130. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(99)00034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahanta PK (1988) Colour and flavour characteristics of made tea. In: Linskens HF, Jackson JF (eds) Modern methods of plant analysis. Analysis of nonalcoholic beverages, vol 8. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, p 223

- 16.Grammer A. Antibiotic sensitivity and assay test. In: Collins CH, Lyne PN, editors. Microbiological methods. London: Butterworths; 1976. p. 235. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Methods for dilution in antimicrobial susceptibility tests, approved standard M2-A5. Villanova: NCCLS; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okubo S, Toda M, Hara Y, Shimamura T. Antifungal and fungicidal activities of tea extract and catechin. Jpn J Bacteriol. 1991;46:509–514. doi: 10.3412/jsb.46.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Gammal AA, Mansour RMA. Antimicrobial activities of some flavonoid compounds. Z Mikrobiol. 1986;141:561–565. doi: 10.1016/s0232-4393(86)80010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stagg GV. Tea—the elements of a cuppa. Nutr Bull. 1980;29:233–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-3010.1980.tb00435.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubo I, Muroi H, Himejima M. Antimicrobial activity of green tea flavor components and their combination effects. J Agric Food Chem. 1992;40:245–248. doi: 10.1021/jf00014a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao WH, Hu ZQ, Okubo S, Hara Y, Shimamura T. Mechanism of synergy between epigallocatechin gallate and beta-lactams against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1737–1742. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.6.1737-1742.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hatano T, Kusuda M, Hori M, Shiota S, et al. Theasinensin A, a tea polyphenol formed from (−)-epigallocatechin gallate, suppresses antibiotic resistance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Planta Med. 2003;69:984–989. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-45142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikigai H, Nakae T, Hara YT, Shimamura T. Bactericidal catechins damage the lipid bilayer. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1993;1147:132–136. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(93)90323-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoda Y, Hu ZQ, Zhao WH, Shimamura T. Different susceptibilities of Staphylococcus and Gram-negative rods to epigallocatechin gallate. J Infect Chemother. 2004;10:55–58. doi: 10.1007/s10156-003-0284-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimamura T, Zhao WH, Hu ZQ. Mechanism of action and potential for use of tea catechin as an antiinfective agent. Antiinfect Agents Med Chem. 2007;6:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caturla N, Vera-Samper E, Villalain J, Mateo CR, Micol V. The relationship between the antioxidant and the antibacterial properties of galloylated catechins and the structure of phospholipid model membranes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:648–662. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)01366-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukai K, Ishigami T, Hara Y. Antibacterial activity of tea polyphenols against phytopathogenic bacteria. Agric Biol Chem. 1991;55:1895–1897. doi: 10.1271/bbb1961.55.1895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]