Sir — Separation of the mitotic spindle at the poles during cell division depends on the action of members of the bimC family of proteins. These proteins are part of the kinesin superfamily of ‘motor’ proteins; molecules that bind microtubules and produce mechanical from chemical energy1. The mechanism of action of bimC motors is not yet known. We report here that the bimC-related KLP61F gene, an essential mitotic gene of the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster, encodes subunits of the bipolar kinesin, KRP130, a homotetrameric complex of four motor subunits, each of relative molecular mass 130,000 (Mr 130K), assembled into a bipolar ‘minifilament’2. This result suggests that bipolar bimC motors work by crosslinking and sliding apart antiparallel microtubules, causing the separation of duplicated spindle poles and allowing bipolar spindle assembly.

To identify the gene encoding the KRP130 subunit, we performed protein microsequencing of purified Drosophila embryonic KRP130 (refs 2, 3). Proteolysis of KRP130 yielded tryptic peptides, which we fractionated, and we selected the seven best-resolved fractions for further analysis. One of these fractions contained a 17-residue peptide, whose sequence we determined. A database search revealed a 100% match of this peptide with a segment of the nonconserved stalk of a previously identified Drosophila bimC-related protein, KLP61F (see figure).

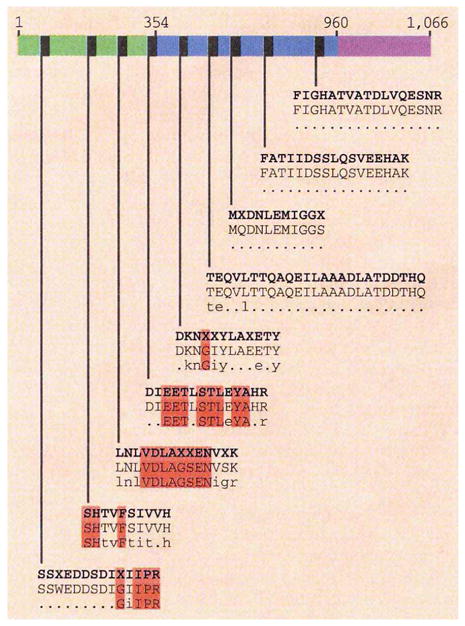

Map based on the amino-acid sequence of Drosophila KLP61F (ref. 5), indicating positions (grey boxes) and amino-acid sequences of KRP130-derived peptides (top rows of sequences), corresponding regions of KLP61F (middle rows), and bimC family consensus sequence (bottom rows). Numbers above indicate amino-acid residues bordering the motor (residues 1-354), stalk (354-960) and tail (960-1,066). Single-letter amino-acid code; X indicates unresolved residues. The indicated peptide sequences correspond to residues 123-136, 231-242, 257-270, 339-352, 391-402, 492-516, 542-552, 669-685 and 880-896 for KLP61F. We found 100% identity between KRP130 and KLP61F sequences, but little or no homology with the bimC family consensus sequence. Residues highlighted in red are identical in all bimC motors. We immobilized sucrose gradient-purified KRP130 on membranes and performed in situ proteolysis with trypsin7. We analysed selected peptides by matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization time-of-flight mass analysis, using α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid as the matrix. The nine unique peptides thus identified matched the predicted masses of KLP61F tryptic fragments (using the MSFIT program at the UCSF mass spectrometry facility to search Drosophila melanogaster proteins in the SwissProt.r33 database). These peptides were analysed by automated Edman degradation, yielding reliable sequences (illustrated). bimC consensus sequences in the indicated regions were determined by lineup comparison of Drosophila KLP61F, Xenopus Eg5, human HsEg5, Aspergillus bimC, Saccharomyces pombe Cut7 and S. cerevisiae CIN8 and KIP1. Full methodological details available on request from J. M. S.

Further analysis of the peptide fractions revealed that they contain a total of nine peptides whose masses match exactly those of the predicted tryptic fragments derived from the Drosophila KLP61F protein sequence4,5. To confirm that KRP130 is identical to KLP61F, we sequenced all nine of these peptides and found that they display 100% identity with the corresponding segments of the deduced KLP61F protein sequence, but differ in many positions from the bimC family consensus sequence (figure). We therefore conclude that a KLP61F polypeptide is identical to a subunit of the bipolar kinesin, KRP130.

This discovery contradicts the hypothesis that KLP61F and KRP130 differ6, and bridges the gap between genetic evidence concerning the biological function of KLP61F (ref. 5), studies of its expression and localization on spindle microtubules5,6, and biochemical and electron-microscope studies of the recombinant polypeptide6 and the native bipolar holoenzyme2,3. For example, in Drosophila KLP61F mutants, the absence of KLP61F function leads to the formation of monopolar spindles with unseparated spindle poles5. This observation, together with the results described here, indicates that the essential mitotic KLP61F gene might encode a slow plus-end-directed microtubule motor polypeptide3,6 that self-assembles into a bipolar homotetrameric holoenzyme2 capable of crosslinking and sliding apart antiparallel microtubules, thereby pushing apart the associated spindle poles during spindle assembly and function.

Contributor Information

A. S. Kashina, Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, University of California, Davis, California 95616, USA

J. M. Scholey, Email: jmscholey@ucdavis.edu, Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, University of California, Davis, California 95616, USA

J. D. Leszyk, Worcester Foundation for Biomedical Research, Shrewsbury, Massachusetts 01545, USA

W. M. Saxton, Department of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana 47405, USA

References

- 1.Walczak CE, Mitchison TJ. Cell. 1996;85:943–946. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kashina AS, et al. Nature. 1996;379:270–272. doi: 10.1038/379270a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cole DG, Saxton WM, Sheehan KB, Scholey JM. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22913–22916. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart RJ, Pesavento PA, Woerpel DN, Goldstein LSB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8470–8474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heck MS, et al. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:665–679. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barton NR, Pereira A, Goldstein LSB. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1563–1574. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.11.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez J, Andrews L, Mische SM. Anal Biochem. 1994;218:112–117. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]