Abstract

As host of the World Conference on Social Determinants of Health on 19–21 October 2011, Brazil has shown its commitment to tackling social factors to improve people’s health and well-being. Minister of Health Alexandre Padilha talks to the WHO Bulletin about what his country has done in this respect and his hopes for the conference.

“There is enough scientific evidence to show that it is possible to do things differently.”

“We cannot now move on into an era of neglecting people with well-known and well-studied diseases.”

Q: Why it is important for Brazil to tackle the social factors that affect health?

A: The new government believes that good health and quality of life can be achieved through the cooperation and collaboration of many government sectors and other partners. Assuring access to health care is a challenge, but since health is the right of each member of the Brazilian population (nearly 200 million people) the issue of access needs to be addressed. The Brazilian Constitution recognizes, under article 196, that “health is a right of all and a duty of the State.” That means that addressing the social determinants of health is both a conceptual and a legal imperative for our government. Brazil firmly believes in universal access and supports all initiatives that promote universal health care. This level of access to health care requires sustainable and predictable financing. The introduction of new technologies is also essential to providing access to treatment for all. There is enough evidence linking health indicators to social issues. On the basis of this evidence we also know, for example, that public policies are fundamental to addressing the social determinants of health.

Q: Brazil has a wide gap between rich and poor in economic terms but it also has a public health system providing a wide range of health services for free. What are the health inequities that Brazil is currently trying to tackle?

A: It is true that throughout history Brazil has been considered one of the most unequal countries in the world. However, many analysts recognize that there have been important advances in the reduction of inequalities in Brazilian society. In the last eight years alone, around 40 million Brazilians were lifted out of poverty and into better conditions. Now the government wants to act on “pockets of poverty”, which include remote areas that still have low visibility and who have little ability to voice their concerns. The goal is to lift these citizens out of extreme poverty and provide them with the conditions to advance in social terms, such as through cash transfers, better education, health care, and so on.

Q: What is the Brazilian government doing to remove social obstacles to health? How is Brazil trying to tackle these health inequalities and what are the challenges it faces? Please give concrete examples.

A: Brazil has been advancing in the development of more democratic and equitable social policies. I could mention the decentralization of health systems and the creation of the Sistema Único de Saúde (Unified Health System), as well as cash transfer policies, such as the Programa Bolsa Família (Family Stipend Programme) as well as an increase in the national minimum wage. Moreover, human and social rights take priority following the creation of the Special Secretariat on Human Rights. Investments have been made in socially inclusive policies that address vulnerable groups. Investments have also been made in initiatives that recognize regional culture, with the creation of the so-called Pontos de Cultura (Culture Spots) that aim to bridge historical discrepancies by linking social development with education, culture and healthy lifestyles. In addition, anti-discrimination policies related to gender, race, sexual orientation and ethnicity have been expanded and innovations in universal access to health services, such as HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention, have been implemented over the last 10 to 15 years. These socio-epidemiological achievements and investments in new technologies, which took place with the participation of civil society, are undeniable. With the new Programa Brasil sem Miséria (Brazil without Extreme Poverty Programme), the Brazilian government is positioning itself as an international actor able to discuss the future of global policies in the new millennium. This discussion is about actions to reduce social inequalities, to improve the quality of life of the population and to put an end to the gap that separates those with the ability to influence and shape public policies and those with no idea that these policies even exist. In our country health is at the centre of the national political agenda. It played a central role in the government plan of the current administration during the 2010 presidential election campaign and health matters constitute a key commitment of the president, Dilma Rousseff, from the moment she took office. As minister of health, I would argue that the health sector is decisive for sustainable development in our country. Brazil spends more than 8% of the national wealth within the health sector, which in addition accounts for some 30% of our research and development efforts. This demonstrates the importance of the health sector for maintaining economic growth, promoting social inclusion and the eradication of extreme poverty. The Brazilian model of public health is inclusive and the Sistema Único de Saúde is its embodiment. Through the Sistema Único de Saúde, every Brazilian is entitled to free health care from clinical care to complex surgical procedures such as organ transplants. This is why we can say with conviction that the Sistema Único de Saúde is an important tool for promoting human dignity.

Q: Is Brazil trying to get health considerations into all government policies? What are the challenges of trying to persuade diverse sectors, agriculture, trade etc. to take health into consideration when forming policies and implementing them? Are there conflicts of interest here?

A: The Programa Brasil sem Miséria has been a key approach to tackling social inequities. There are still great intersectoral challenges, such as fighting hunger, poverty, drug addiction, infant and maternal mortality, violence, environmental degradation and chronic diseases. The Programa Bolsa Família is an example of the collaboration between sectors that we have been seeking. It is a cash transfer programme and constitutes one of the largest and most successful poverty reduction policies in Brazil. This programme directly contributes to the improvement of the quality of life of the Brazilian people. To receive these payments, families must meet certain requirements, including keeping children up to date with vaccinations and ensuring that pregnant women attend at least six prenatal checkups. Another initiative relates to the purchase of food for schools. The incentive is for schools to purchase food from small farmers, who are covered by the Programa de Agricultura Familia (Family Farming Programme). This food is fresh and nutritious and, thus, the programme creates a virtuous cycle between agriculture, education, nutrition and health. Intersectoral public policies, as in many other parts of the world, are still an important challenge for all three spheres of the Brazilian government. We shall learn a lot from other countries at the Conference in Rio.

Q: What does Brazil hope to achieve by hosting the World Conference on Social Determinants of Health?

A: As a continent-wide country, Brazil would like to make a pact with other countries to eradicate poverty and hunger. The conference, whose motto is “all for equity”, seeks to promote a global agenda calling for a joint effort to change today’s alarming situation. There is enough scientific evidence to show that it is possible to do things differently. Political will and cooperation between countries are fundamental. We have to launch a proactive and rational agenda that encompasses the food, pharmaceutical, arms, tobacco and alcohol industries. We need action to develop and increase the wealth of peoples, setting ourselves the end of extreme poverty and environmental sustainability as our goals. This year is particularly important for global health. In September, we had the United Nations High-level Meeting on Non-Communicable Diseases. In Brazil, noncommunicable diseases are responsible for 72% of deaths and present the greatest challenge for the health sector. These are problems that particularly affect the poor and vulnerable. Obesity, hypertension, tobacco use, alcohol abuse and physical inactivity are predominant especially in populations with lower incomes and less education. The last two United Nations meetings on health – on polio and HIV/AIDS – point to the same direction in solving both challenges: equality in the access to prevention measures and treatment. Having fought neglected diseases in Brazil – a fight that continues to this day – we must remember the lessons from the past. We cannot now move on into an era of neglecting people with well-known and well-studied diseases. The Brazilian Ministry of Health has carried out a broad public consultation to prepare a plan to address noncommunicable diseases. The prevention and control of these diseases will be the subject of a set of political and governmental policies. Meanwhile, we are concerned that the global crisis – which has economic, social, environmental, food, energy, ethnic and health dimensions – could make global health inequalities even worse for poor countries. The Conference in Rio – like the United Nations meeting last month – will gather many different government sectors, as well as civil society, researchers in the field and United Nations agencies to produce a high-level political pact and to introduce effective tools to address the social determinants of health.

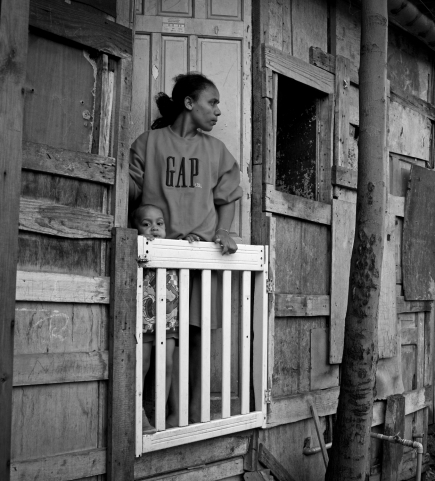

Mother and child in Sao Paulo slums

WHO/Anna Kari

Biography

Alexandre Padilha was appointed Minister of Health in the new Brazilian cabinet in January 2011. He earned his medical degree at the State University of Campinas, Brazil. From 1991 to 1993, he was coordinator of the Student's Union at his university and member of the governing council of the Workers' Party in the state of Sao Paulo. He held several positions in the government of the former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

Courtesy of the Ministry of Health, Brazil

Alexandre Padilha