Abstract

Objective

To carry out a descriptive analysis of mesothelioma deaths reported worldwide between 1994 and 2008.

Methods

We extracted data on mesothelioma deaths reported to the World Health Organization mortality database since 1994, when the disease was first recorded. We also sought information from other English-language sources. Crude and age-adjusted mortality rates were calculated and mortality trends were assessed from the annual percentage change in the age-adjusted mortality rate.

Findings

In total, 92 253 mesothelioma deaths were reported by 83 countries. Crude and age-adjusted mortality rates were 6.2 and 4.9 per million population, respectively. The age-adjusted mortality rate increased by 5.37% per year and consequently more than doubled during the study period. The mean age at death was 70 years and the male-to-female ratio was 3.6:1. The disease distribution by anatomical site was: pleura, 41.3%; peritoneum, 4.5%; pericardium, 0.3%; and unspecified sites, 43.1%. The geographical distribution of deaths was skewed towards high-income countries: the United States of America reported the highest number, while over 50% of all deaths occurred in Europe. In contrast, less than 12% occurred in middle- and low-income countries. The overall trend in the age-adjusted mortality rate was increasing in Europe and Japan but decreasing in the United States.

Conclusion

The number of mesothelioma deaths reported and the number of countries reporting deaths increased during the study period, probably due to better disease recognition and an increase in incidence. The different time trends observed between countries may be an early indication that the disease burden is slowly shifting towards those that have used asbestos more recently.

ملخص

الغرض

إجراء تحليل وصفي لوفيات ورم المتوسطة المُبلغ عنها على الصعيد العالمي بين عامي 1994 و 2008.

الطريقة

استخلص الباحثون معطيات وفيات ورم المتوسطة المُبلغ عنها من قاعدة معطيات الوفيات التابعة لمنظمة الصحة العالمية منذ عام 1994، حين بدأ تسجيل المرض لأول مرة. كما سعى الباحثون وراء المعلومات الموجودة في المصادر المكتوبة باللغة الإنكليزية. وحسبت معدلات الوفيات الخام والمعدلات المصححة بالعمر، وجرى تقييم لاتجاهات الوفيات عن طريق التغير في النسبة المئوية السنوية لمعدل الوفيات المصحح بالعمر.

النتائج

لقد أُبلغ عن وقوع 92253 وفاة من قبل 83 بلداً. وكان معدل الوفيات الخام 6.2 ومعدل الوفيات المصحح بالعمر 4.9 وفاة لكل مليون شخص من السكان. ازداد سنوياً معدل الوفيات المصحح بالعمر بمقدار 5.37%، ونتيجة لذلك ازداد إلى أكثر من الضعف في غضون فترة الدراسة. وكان متوسط العمر وقت الوفاة هو 70 عاماً، وكانت نسبة الذكور إلى الإناث هي 3.6:1. وتَوَزّع المرض حسب موقع حدوثه التشريحي في: الجنبة 41.3%؛ الصفاق 4.5%؛ التامور 0.3%؛ ومواقع غير محددة 43.1%. وتجانف التوزيع الجغرافي للوفيات نحو البلدان المرتفعة الدخل: وأبلغت الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية عن أعلى عدد، بينما وقعت أكثر من 50% من جميع الوفيات في أوروبا. وبالمقارنة، وقعت أقل من 12% من الوفيات في البلدان المتوسطة والمنخفضة الدخل. وفي المجمل تزايد اتجاه معدل الوفيات المصحح بالعمر في أوروبا واليابان، ولكنه كان يتراجع في الولايات المتحدة.

الاستنتاج

ازداد عدد وفيات ورم المتوسطة المُبْلَغ عنه وعدد البلدان التي تبلغ عنه أثناء فترة الدراسة، وقد يرجع ذلك إلى تحسّن سبل اكتشاف المرض وزيادة معدل وقوعه. وقد يكون التباين في الاتجاهات الزمنية الملاحظة بين البلدان إشارةً مبكرةً على أن عبء المرض ينتقل ببطء نحو البلدان الأكثر حداثة في استخدام الأسبست.

Resumen

Objetivo

Llevar a cabo un análisis descriptivo de las muertes por mesotelioma notificadas en todo el mundo entre los años 1994 y 2008.

Métodos

Hemos recopilado datos sobre muertes por mesotelioma notificadas a la base de datos de mortalidad de la Organización Mundial de la Salud desde 1994, cuando se registró por primera vez la enfermedad. También hemos obtenido información de otras fuentes de lengua inglesa. Se calcularon las tasas de mortalidad bruta y de mortalidad ajustada en función de la edad, y se evaluaron las tendencias de mortalidad a partir del cambio en el porcentaje anual de la tasa de mortalidad ajustada en función de la edad.

Resultados

En total, se notificaron 92 253 muertes por mesotelioma en 83 países. Las tasas de mortalidad bruta y de mortalidad ajustada en función de la edad fueron de 6,2 y 4,9 por millón de habitantes, respectivamente. La tasa anual de mortalidad ajustada en función de la edad aumentó en un 5,37% y, en consecuencia, se duplicó durante el periodo de estudio. La edad media en el momento del fallecimiento fue de 70 años y la proporción hombre-mujer fue de 3.6:1. La distribución de la enfermedad por regiones anatómicas fue: pleura, 41,3%; peritoneo, 4,5%; pericardio, 0,3%; y lugares no especificados, 43,1%. La distribución geográfica de las muertes mostró una mayor tendencia en los países de renta alta: los Estados Unidos de América registraron el número más elevado, mientras que más del 50% de todas las muertes se produjeron en Europa. Por el contrario, menos de un 12% de las muertes se produjeron en países de renta media o baja. La tendencia generalizada en la tasa de mortalidad ajustada en función de la edad fue aumentando en Europa y Japón, mientras que en los Estados Unidos fue descendiendo.

Conclusión

Durante el periodo de estudio, se observó un aumento en el número de muertes notificadas por mesotelioma y en el número de países que notificaron muertes por mesotelioma. Probablemente, esto se debe a una mejora en el reconocimiento de la enfermedad y a un aumento de su incidencia. Las diferentes tendencias entre países observadas en el tiempo, se pueden convertir en un indicador temprano de que la carga de la enfermedad está cambiando lentamente hacia aquellos países que han utilizado amianto más recientemente.

Résumé

Objectif

Réaliser une analyse descriptive des décès par mésothéliome, rapportés à l’échelle mondiale entre 1994 et 2008.

Méthodes

Nous avons extrait les données sur les décès par mésothéliome rapportés à la base de données de mortalité de l'Organisation mondiale de la Santé depuis 1994, lorsque la maladie a été enregistrée pour la première fois. Nous avons également cherché des informations à partir d'autres sources en langue anglaise. Les taux de mortalité brut et ajusté selon l'âge ont été calculés, et les tendances de la mortalité ont été évaluées à partir de la modification du pourcentage annuel du taux de mortalité ajusté selon l'âge.

Résultats

Au total, 92 253 décès par mésothéliome ont été signalés par 83 pays. Les taux de mortalité brut et ajusté selon l'âge étaient de 6,2 et 4,9 par million d'habitants, respectivement. Le taux de mortalité ajusté selon l'âge a augmenté de 5,37% par an et a, par conséquent, plus que doublé au cours de la période d'étude. L'âge moyen au décès était de 70 ans et le ratio hommes-femmes était de 3,6:1. La distribution de la maladie selon le site anatomique était la suivante: plèvre, 41,3%; péritoine, 4,5%; péricarde, 0,3%, et sites non précisés, 43,1%. La répartition géographique des décès était biaisée vers les pays à revenus élevés: les États-Unis d'Amérique en ont signalé le plus grand nombre, tandis que plus de 50% de tous les décès sont survenus en Europe. En revanche, moins de 12% des décès sont survenus dans les pays à revenus faible et moyen. La tendance générale du taux de mortalité ajusté selon l'âge était en augmentation en Europe et au Japon, mais en baisse aux États-Unis.

Conclusion

Le nombre de décès par mésothéliome rapportés et le nombre de pays rapportant des décès ont augmenté au cours de la période d'étude, probablement en raison d'une meilleure identification de la maladie et d'une augmentation de l'incidence. Les différentes tendances au cours du temps observées entre les pays peuvent être une indication précoce du fait que la charge de morbidité se déplace lentement vers les personnes qui ont plus récemment utilisé l'amiante.

Резюме

Цель

Провести описательный анализ случаев смерти от мезотелиомы в мире, зафиксированных в 1994–2008 гг.

Методы

Мы выделили данные по случаям смерти от мезотелиомы, зафиксированным в базе данных ВОЗ о смертности, начиная с 1994 года, когда сведения по данному заболеванию начали впервые учитываться в базе данных. Мы также провели поиск информации по другим англоязычным источникам. Рассчитывались общий и стандартизированный по возрасту коэффициенты смертности. Тенденции в изменении смертности оценивались как годовое процентное изменение в стандартизированной по возрасту смертности.

Результаты

Всего было зарегистрировано 92 253 случая смерти от мезотелиомы в 83 странах. Общий коэффициент и стандартизированная по возрасту смертность составили 6,2 и 4,9 случаев на один миллион населения соответственно. Стандартизированная по возрасту смертность растет на 5,37% в год, и в результате более чем удвоилась за изучаемый период времени. Средний возраст на момент смерти составлял 70 лет, и отношение показателя мужчин к показателю женщин было 3,6:1. Распределение заболевания по анатомической локализации: плевра – 41,3%, брюшная полость – 4,5%, перикард – 0,3%, неуточненная локализация – 43,1%. Географическое распределение случаев смерти смещалось в сторону стран с высоким доходом: о наибольшем числе смертей сообщили Соединенные Штаты Америки, в то время как 50% всех случаев смерти отмечено в Европе. Напротив, менее чем 12% случаев смерти произошли в странах со средним и низким доходом. Общая тенденция стандартизированного по возрасту коэффициента смертности увеличивалась в Европе и Японии, но уменьшалась в США.

Вывод

Количество сообщений о случаях смерти от мезотелиомы и число стран, предоставивших данные о смертности, за изучаемый период увеличились, вероятно, вследствие лучшего распознавания заболевания и увеличения заболеваемости. Различия во временных тенденциях, наблюдаемых в разных странах, могут быть опережающим индикатором смещения бремени заболеваемости в страны, вплоть до недавнего времени использовавшие асбест.

摘要

目的

旨在对1994-2008年间全球范围内报告的间皮瘤死亡人数进行描述性分析。

方法

我们提取了自1994年该疾病首次记录以来向世界卫生组织死亡数据库报告的间皮瘤死亡数据。我们还从其他的英语语言来源检索了相关信息。同时对粗死亡率和年龄调整死亡率进行计算,并从年龄调整死亡率的年度百分比变化评估死亡率趋势。

结果

总共有83个国家报告了92 253例间皮瘤死亡。粗死亡率和年龄调整死亡率分别为每百万人群6.2例和4.9例。年龄调整死亡率每年增加5.37%,而在整个研究期间则翻了一番。死亡的平均年龄是70岁,男女比例为3.6:1。从解剖部位看,疾病的分布为:胸膜,41.3%;腹膜,4.5%;心包,0.3%;非指定部位,43.1%。死亡的地理分布向高收入国家偏移:美国报告的死亡人数最多,而超过50%的死亡率发生在欧洲。相比之下,仅有低于12%的死亡发生在中低收入国家。年龄调整死亡率在欧洲和日本总体呈上升趋势,而在美国整体呈下降趋势。

结论

研究期间所报告的间皮瘤死亡人数和报告死亡人数的国家数量均有所增加,可能由于有更好的疾病识别能力,同时该病的发病率也再增加。所观察到的国家间的不同时间趋势可能表明疾病负担正在慢慢向那些近来使用石棉的国家转移的一个早期迹象。

Introduction

Malignant mesothelioma is a rare but fatal form of cancer which is difficult to diagnose. The disease is causally linked to asbestos exposure with an etiological fraction of 80% or more.1,2 It has been reported that the incidence is much higher in men than women.3 The latency period for mesothelioma after initial exposure to asbestos is typically longer than 30 years and the median survival time after diagnosis is 9–12 months.3 The World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized that asbestos is one of the most important occupational carcinogens and that the burden of asbestos-related disease is rising. Consequently, WHO has declared that asbestos-related diseases should be eliminated throughout the world.4

The global mesothelioma burden is unclear. Driscoll et al. estimated that as many as 43 000 people worldwide die from the disease each year.5 It has also been estimated that there are around 10 000 mesothelioma cases annually in Australia, Japan, North America and western Europe combined.1 In addition, Park et al. suggested that one mesothelioma case may be overlooked for every four to five recorded.6 Reports of an increase in the incidence of mesothelioma have been published in a wide range of countries.7–11 However, to date there is no established global baseline that can be used to evaluate trends in disease occurrence.

Since 1994, data on mesothelioma deaths have been included in the WHO mortality database, which records deaths in WHO Member States in each calendar year. Data are specified by disease category, gender and 5-year age intervals and are integrated across countries using a common format.12 Data comparability improved with the introduction of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD),13 though the category “malignant mesothelioma” was included only in 1993 with the 10th revision (ICD-10).14 However, as acknowledged by WHO, accuracy in diagnosing causes of death varies among countries.13 By 30 January 2011, mesothelioma death figures were available for a 15-year period. The aim of this study was to improve the understanding and management of malignant mesothelioma by carrying out a descriptive analysis of global data available on deaths caused by the disease.

Methods

We extracted the numbers of mesothelioma deaths recorded in the WHO mortality database as malignant mesothelioma (i.e. ICD-10 category C45 or any subcategory thereof) between 1994 and 2008. In addition, we conducted a literature search of PubMed to identify papers published in English that could provide useful information on national mesothelioma data. However, the data identified lacked detailed information on the numbers of deaths (e.g. on year, age group and gender). Consequently, we used only data from the WHO mortality database in the analysis.

The number of deaths was summed by calendar year and country and was stratified according to demographic characteristics, including gender and anatomical disease site. To calculate mortality rates, national population data were obtained from the WHO health statistics and health information systems12 and the United States Census Bureau,15 with priority being given to WHO data.

National counts were further aggregated by region and income level. We merged the smaller regions defined by the United Nations Statistics Division16 into the five continents: Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe and Oceania. In addition, we adapted the World Bank categories of national income level17 to form three categories: low, middle and high income. The World Bank “upper middle” and “lower middle” categories were merged into the middle category.

National data on mesothelioma deaths were available for 1 to 15 years, depending on the country. As a consequence, the number of countries that reported data in any particular year ranged from 3 to 57. This variability was taken into account when calculating the mortality rate for a group of countries by ensuring that any particular country contributed data to both the numerator and denominator of the rate calculation only in those calendar years during which mesothelioma data were available for that country. Age-adjusted mortality rates were calculated using a direct age-adjustment method, with reference to the world population in the year 2000.18

To assess disease trends over time, we analysed the data from countries that had reported deaths due to mesothelioma for more than 5 years. Regression analysis was used to determine how the age-adjusted mortality rate varied by calendar year. A log–linear trend was assumed and weighting was applied for the size of population at risk each year. To characterize the time trend in the age-adjusted mortality rate, we calculated the annual percentage change in the rate using the slope (i.e. the b value) obtained in the regression model, such that the annual percentage change equalled 100 × (10b – 1). In addition, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P-values were calculated for the annual percentage change.

Data compilation and descriptive statistical analyses were carried out using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, United States of America). Regression analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, USA). A P-value less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the study data on all mesothelioma deaths recorded in the WHO mortality database for the period 1994 to 2008. During this time, 92 253 deaths were reported in 83 countries. The crude and age-adjusted mortality rates for all mesothelioma deaths were 6.2 and 4.9 per million population, respectively, and the mean age at death was 70 years. The gender-specific age-adjusted mortality rate for males was 9.0 per million compared with 1.9 per million for females and the male-to-female ratio was 3.6:1.

Table 1. Mesothelioma deaths in the mortality database of the World Health Organization, worldwide, 1994–2008.

| Characteristic | Deaths |

No. of countries reporting deaths | Age at death (years) |

AAMR (per million) | M:F ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | Mean | SD | ||||

| Total | 92 253 | 100.0 | 83 | 70.0 | 11.6 | 4.9 | 3.6:1 |

| Sexa | |||||||

| Male | 72 000 | 78.0 | 81 | 69.9 | 11.2 | 9.0 | NA |

| Female | 20 252 | 22.0 | 73 | 70.2 | 13.1 | 1.9 | NA |

| Anatomical disease siteb | |||||||

| Pleura | 38 121 | 41.3 | 58 | 70.1 | 11.0 | 2.3 | 3.7:1 |

| Peritoneum | 4 116 | 4.5 | 43 | 66.0 | 12.6 | 0.3 | 1.6:1 |

| Pericardium | 298 | 0.3 | 30 | 61.1 | 15.6 | 0.03 | 1.8:1 |

| Other sites | 6 184 | 6.7 | 53 | 70.7 | 12.4 | 0.4 | 3.2:1 |

| Unspecified | 39 726 | 43.1 | 65 | 70.9 | 11.5 | 2.3 | 4.0:1 |

| Site not reported | 3 808 | 4.1 | 16 | 63.6 | 12.8 | 2.6 | 2.6:1 |

| Continent | |||||||

| Africa | 2 333 | 2.5 | 4 | 63.4 | 12.7 | 4.8 | 3.3:1 |

| Americas | 23 869 | 25.9 | 36 | 70.5 | 12.7 | 3.6 | 3.3:1 |

| Asia | 12 012 | 13.0 | 11 | 69.5 | 12.2 | 2.6 | 3.2:1 |

| Europe | 49 779 | 54.0 | 30 | 70.1 | 10.9 | 7.2 | 3.7:1 |

| Oceania | 4 260 | 4.6 | 2 | 71.3 | 10.6 | 16.0 | 5.6:1 |

| Country income groupc | |||||||

| High | 81 313 | 88.1 | 39 | 70.9 | 10.9 | 6.3 | 3.9:1 |

| Middle | 10 906 | 11.8 | 37 | 63.2 | 14.0 | 1.9 | 1.9:1 |

| Low | 22 | 0.02 | 2 | 54.8 | 16.7 | 0.4 | 3.4:1 |

| Not available | 12 | 0.01 | 5 | 67.5 | 11.4 | NAd | 5.0:1 |

| Reporting period | |||||||

| 1994–2000 | 22 305 | 24.2 | 63 | 68.4 | 12.5 | 4.0 | 3.2:1 |

| 2001–2008 | 69 948 | 75.8 | 77 | 70.5 | 11.3 | 5.3 | 3.7:1 |

| 10 countries reporting the highest number of deaths (no. of reporting years) | |||||||

| United States of America (7) | 17 062 | 18.5 | NA | 72.8 | 11.1 | 5.0 | 4.2:1 |

| United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (9) | 13 517 | 14.6 | NA | 71.3 | 9.9 | 17.8 | 5.7:1 |

| Japan (14) | 11 212 | 12.1 | NA | 70.0 | 11.9 | 3.2 | 3.3:1 |

| Germany (9) | 9 569 | 10.4 | NA | 70.3 | 10.6 | 6.8 | 3.2:1 |

| France (8) | 6 608 | 7.2 | NA | 71.8 | 10.5 | 7.6 | 3.4:1 |

| Netherlands (13) | 5 141 | 5.6 | NA | 70.0 | 10.2 | 6.4 | 4.0:1 |

| Australia (8) | 3 747 | 4.1 | NA | 71.3 | 10.7 | 16.5 | 5.4:1 |

| Italy (3) | 3 706 | 4.0 | NA | 71.2 | 10.6 | 10.3 | 2.4:1 |

| South Africa (12) | 2 322 | 2.5 | NA | 63.4 | 12.7 | 6.7 | 3.3:1 |

| Spain (7) | 1 840 | 2.0 | NA | 67.8 | 12.2 | 3.9 | 2.9:1 |

AAMR, age-adjusted mortality rate; M:F, male to female; NA, not applicable; SD, standard deviation.

a In one case, sex was not specified.

b Anatomical sites were classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision as: C45.0, pleura; C45.1, peritoneum; C45.2, pericardium; C45.7, other sites; C45.9, unspecified.

c Country income groups were based on adapted World Bank categories of national income level.

d Population data were not available.

With regard to anatomical site, the pleura accounted for 41.3% of all mesothelioma deaths and unspecified sites, for 43.1%, far outnumbering the peritoneum and pericardium, which accounted for 4.5% and 0.3% of deaths, respectively. The male-to-female ratio was higher for unspecified sites, the pleura and other sites, at 4.0:1, 3.7:1 and 3.2:1, respectively, compared with 1.8:1 and 1.6:1 for the pericardium and peritoneum, respectively. In fact, mesothelioma of the peritoneum was more than twice as common in females as in males (7.7% versus 3.6%, respectively; data not shown in the table). By anatomical site, the age-adjusted mortality rate was 2.3, 2.3 and 0.3 per million for the pleura, unspecified sites and the peritoneum, respectively. The mean age at death by anatomical site was highest for unspecified sites, at 70.9 years, while it was 70.1 years for patients with pleural mesothelioma and 70.7 years for the category of other sites. Again, findings for these sites contrasted with those for the peritoneum and pericardium, for which the mean age at death was 66.0 and 61.1 years, respectively.

When mesothelioma deaths were analysed by continent, most were found to occur in Europe: almost 50 000 deaths and 54.0% of all deaths worldwide. Moreover, 45% of deaths in Europe were in western regions, while 36% were in northern regions (data not shown in the table). Outside of Europe, mesothelioma deaths occurred most commonly in the Americas and Asia, which accounted for 25.9% and 13.0% of all deaths, respectively. Oceania, which comprised Australia and New Zealand in this study, accounted for 4.6% of all deaths but recorded the highest age-adjusted mortality rate, of 16.0 per million. The second highest was for Europe, at 7.2 per million.

Analysis by national income level showed that 88% and 12% of deaths occurred in high- and middle-income countries, respectively, with almost no deaths recorded in low-income countries. Deaths were concentrated in a relatively small number of countries: 45.2% occurred in either Japan, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland or the United States of America, while 81.0% occurred in the 10 countries that reported the most deaths. By country, the United Kingdom had the highest age-adjusted mortality rate, at 17.8 per million, followed by Australia, at 16.5 per million, and Italy, at 10.3 per million.

More than three quarters of all deaths were reported after 2000: the corresponding age-adjusted mortality rate was 5.3 per million during 2001 to 2008 compared with 4.0 per million during 1994 to 2000.

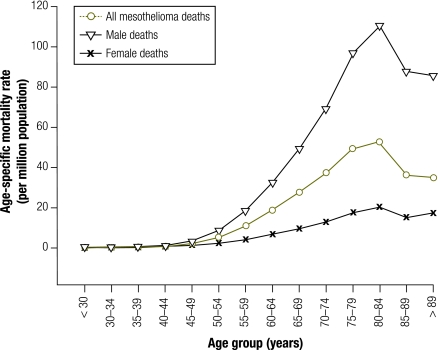

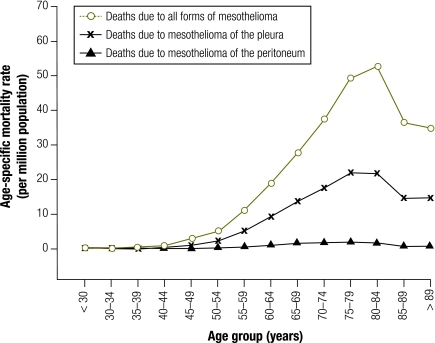

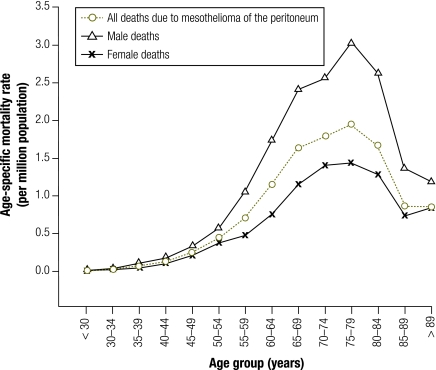

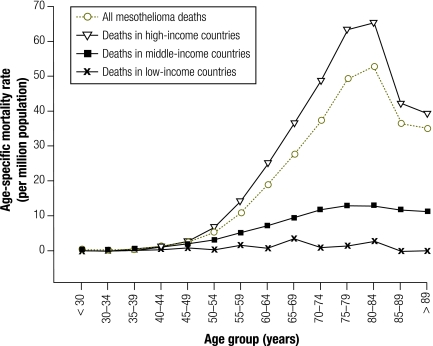

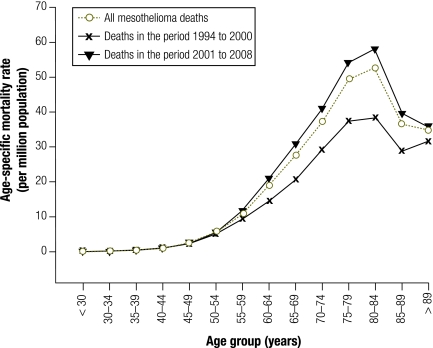

Age-specific mesothelioma mortality rates for men and women separately and combined are illustrated by age group in Fig. 1. The rate was relatively unchanging at below 10 mesothelioma deaths per million up to 55 years of age, then increased sharply to a peak of 54 per million for individuals aged 75 to 89 years. In men, the rate peaked at 113 per million in the 80–84-year age group; in women, it peaked at 21 per million in the same age group. For pleural mesothelioma, a peak in mortality between the ages of 75 and 89 years was also clearly observed (Fig. 2; available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/89/10/11-086678). For peritoneal mesothelioma, an age peak was noted for individuals aged 65 to 84 years (Fig. 3; available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/89/10/11-086678). Graphs of the age-specific mesothelioma mortality rates for different national income levels demonstrated the same age peak for high-income countries (Fig. 4; available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/89/10/11-086678). The peak was less noticeable for middle-income countries and much less clear for low-income countries. When the age-specific mortality rate was analysed for the two observation periods, the age peak was present for both the 1994 to 2000 period and the 2001 to 2008 period, though the rate was 1.5-fold higher during 2001 to 2008 (Fig. 5; available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/89/10/11-086678).

Fig. 1.

Age-specific mesothelioma mortality rate, by age group and gender, worldwide, 1994–2008a

a In total, 71 975 mesothelioma deaths in males and 20 248 deaths in females were reported. The difference between these figures and those recorded in the WHO Mortality Database are due to unavailable data on population, age or sex.

Fig. 2.

Age-specific mesothelioma mortality rate, by age group and disease site, worldwide, 1994–2008a

a Of a total of 92 224 mesothelioma deaths, 38 111 were due to mesothelioma of the pleura and 4116 were due to mesothelioma of the peritoneum. The difference between these figures and those recorded in the WHO Mortality Database are due to unavailable data on population or age.

Fig. 3.

Age-specific peritoneal mesothelioma mortality rate, by age group and gender, worldwide, 1994–2008a

a Of the 4116 deaths due to mesothelioma of the peritoneum, 2556 occurred in males and 1560 in females.

Fig. 4.

Age-specific mesothelioma mortality rate, by age group and country income, worldwide 1994–2008a

a Of the 92 224 mesothelioma deaths reported by 83 countries, 81 304 were reported by 39 high-income countries, 10 897 were reported by 37 middle-income countries and 22 were reported by two low-income countries. The difference between these figures and those recorded in the WHO Mortality Database are due to unavailable data on population or age.

Fig. 5.

Age-specific mesothelioma mortality rate, by age group and reporting period, worldwide, 1994–2008a

a Of 92 224 mesothelioma deaths, 22 291 occurred between 1994 and 2000, while 69 933 occurred between 2001 and 2008. The difference between these figures and those recorded in the WHO Mortality Database are due to unavailable data on population or age.

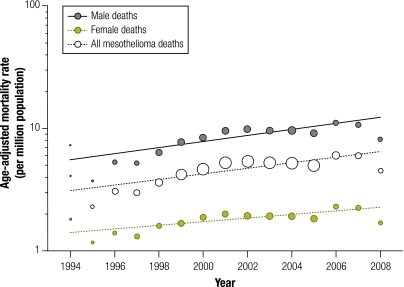

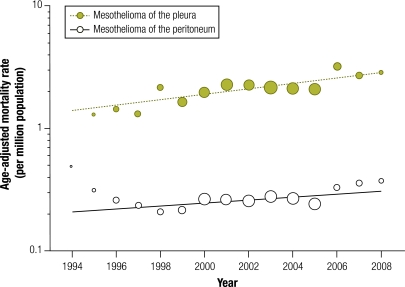

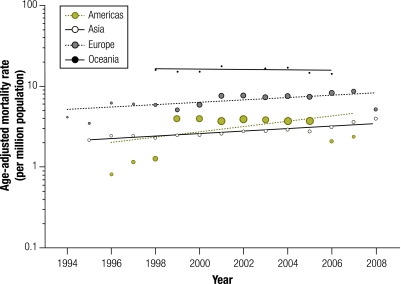

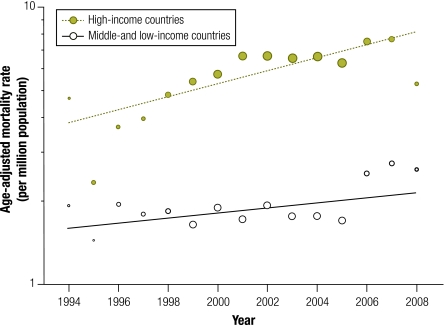

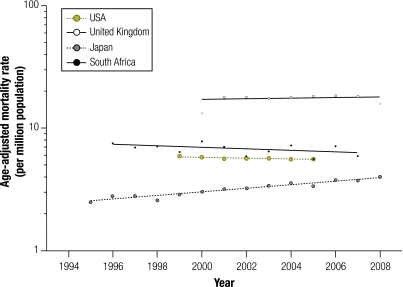

Forty-six countries reported deaths due to mesothelioma for more than 5 years, with the data covering a total of 85 512 deaths. Table 2 summarizes the findings of the regression analysis carried out using these data to characterize the time trend in the age-adjusted mortality rate. For the analysis, the data were stratified by gender and other attributes. For all mesothelioma deaths, the age-adjusted mortality rate increased significantly at an annual rate of 5.37%. The annual increase in men, at 5.85%, was more than 60% greater than in women, at 3.48% (Fig. 6). When data were analysed by the anatomical site of the mesothelioma, the increasing trend was most apparent for the category of unspecified sites, for which the annual increase was 7.80%. The second most rapid increase was for pleural mesothelioma, at 5.20%, followed by peritoneal mesothelioma, at 2.78% (Fig. 7). Analysis of the trend in different continents showed a significant annual increase of 3.67% in Asia and of 3.44% in Europe (Fig. 8; available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/89/10/11-086678). In addition, there was a significant annual increase of 5.54% in high-income countries, but no significant increase in middle- and low-income countries (Fig. 9). Finally, analysis of data from selected countries identified a significant annual increase of 3.46% in Japan and a significant annual decrease of 0.84% in the United States (Fig. 10).

Table 2. Regression analysis of time trend in age-adjusteda mesothelioma mortality rate, worldwide, 1994–2008.

| Category | Regression parameterb |

Annual change |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b or slope | 95% CI | P | % | 95% CI | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 0.02 | 0.01 to 0.04 | 0.0003 | 5.85 | 3.25 to 8.51 | |

| Female | 0.01 | 0.01 to 0.02 | 0.0008 | 3.48 | 1.74 to 5.26 | |

| All | 0.02 | 0.01 to 0.03 | 0.0002 | 5.37 | 3.06 to 7.74 | |

| Anatomical disease site | ||||||

| Pleura | 0.02 | 0.01 to 0.03 | 0.0006 | 5.20 | 2.67 to 7.78 | |

| Peritoneum | 0.01 | 0.003 to 0.02 | 0.0166 | 2.78 | 0.59 to 5.03 | |

| Unspecified | 0.03 | 0.01 to 0.05 | 0.0040 | 7.80 | 2.90 to 12.93 | |

| Continentc | ||||||

| Americas | 0.03 | −0.01 to 0.08 | 0.1148 | 7.89 | −2.18 to 18.99 | |

| Asia | 0.02 | 0.01 to 0.02 | < 0.0001 | 3.67 | 2.64 to 4.71 | |

| Europe | 0.01 | 0.003 to 0.03 | 0.0149 | 3.44 | 0.78 to 6.17 | |

| Oceania | −0.002 | −0.01 to 0.01 | 0.6295 | −0.51 | −2.90 to 1.92 | |

| Country income group | ||||||

| High | 0.02 | 0.01 to 0.04 | 0.0010 | 5.54 | 2.66 to 8.50 | |

| Middle and lowd | 0.01 | −0.001 to 0.02 | 0.0621 | 2.16 | −0.12 to 4.51 | |

| Selected countries | ||||||

| United States of America | −0.004 | −0.01 to −0.001 | 0.0076 | −0.84 | −1.34 to −0.34 | |

| United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland | 0.003 | −0.004 to 0.01 | 0.3403 | 0.68 | −0.88 to 2.27 | |

| Japan | 0.01 | 0.01 to 0.02 | < 0.0001 | 3.46 | 2.86 to 4.07 | |

| South Africa | −0.01 | −0.01 to 0.001 | 0.0959 | −1.47 | −3.22 to 0.31 | |

CI, confidence interval.

a Ages were adjusted to the world standard population in 2000.

b A log–linear regression model was used to analyse the variation in the logarithm of the age-adjusted mortality rate with calendar year. Weighting was applied for each country’s population.

c Africa was excluded because the only country that satisfied the inclusion criteria for the trend analysis was South Africa, which is listed as a selected country.

d Middle- and low-income countries were combined because only one low-income country satisfied the inclusion criteria for the trend analysis.

Fig. 6.

Time trend in age-adjusted mesothelioma mortality rate, by gender, worldwide, 1994–2008

Note: The diameter of each circle is proportional to the size of the population at risk.

Fig. 7.

Time trend in age-adjusted mortality rate for pleural and peritoneal mesothelioma, worldwide, 1994–2008

Note: The diameter of each circle is proportional to the size of the population at risk.

Fig. 8.

Time trend in age-adjusted mesothelioma mortality rate in selected continents,a 1994–2008b

a Africa was excluded because the only country that satisfied the inclusion criteria for the trend analysis was South Africa, which is reported in Fig. 10.

Note: The diameter of each circle is proportional to the size of the population at risk.

Fig. 9.

Time trend in age-adjusted mesothelioma mortality rate, by country income,a worldwide, 1994–2008

a Data from 23 high-income and 23 middle- and low-income countries were included.

Note: The diameter of each circle is proportional to the size of the population at risk.

Fig. 10.

Time trend in age-adjusted mesothelioma mortality rate in selected countries, 1994–2008

USA, United States of America.

Note: The diameter of each circle is proportional to the size of the population at risk.

Discussion

Our examination of the WHO mortality database through a 15-year window identified over 92 000 deaths from mesothelioma in a total of 83 countries. Although the poor comparability of data from different countries in this database is well recognized,13 we felt that analysing combined mortality data could be justified for several reasons. First, concerns about potential mesothelioma epidemics at a national or regional level are growing and the disease has been targeted for prevention and elimination. Second, because mesothelioma is rare, few international data are available. Third, mortality data may offer an insight into the morbidity associated with this fatal disease and may aid prevention strategies.

The pattern of mesothelioma we found is inevitably affected by the way countries report data to WHO. The number of countries that submitted underlying cause-of-death data using ICD-10 increased from 4 in 1995, to 75 in 2003, to over 100 in 2007, although about 10 countries continued to use ICD-9.13 Three countries reported mesothelioma deaths in 1995, compared with 54 in 2003 and 34 in 2007. The figures for more recent years will probably be revised as data entry continues.

The combined population of the countries reporting data on mesothelioma deaths comprised approximately 29% of the world’s population in 2000: 95% of high-income countries, 27% of middle-income countries and 1% of low-income countries. This limited representation is due to the absence of data from populous countries such as China, India and Indonesia.19 Although the number of countries submitting data is increasing, most deaths reported remain concentrated in a small group of countries: over 80% occurred in the 10 countries that reported the highest number of deaths and over 50% occurred in Europe. By contrast, 26 countries (31%) reported fewer than 10 cumulative mesothelioma deaths each. Data validity may be problematic in these countries. However, underreporting is a common problem with rare diseases that are difficult to diagnose. Without immunohistochemical staining, mesothelioma is often misdiagnosed as lung adenocarcinoma.3,20 In this study, we did not include “malignant neoplasm of the pleura” (ICD-9 category 163), although this condition is generally compatible with malignant mesothelioma of the pleura. Hence, our data may underestimate mesothelioma deaths occurring worldwide.

Regression analysis, under the assumption of a log–linear trend, showed that age-adjusted mortality rates increased significantly over time. This suggests that mortality was rising exponentially. The annual change of around 5% we found corresponds to a more than twofold increase in the age-adjusted mortality rate during the 15-year study period. This rise probably reflects both better disease detection and a real increase in incidence.

Statistically, the increased mortality rate was influenced by trends in high-income countries, which reported 88% of all mesothelioma deaths. For example, there was a significant decrease in the United States, which ranked first in the number of deaths, a nonsignificant increase in the United Kingdom, which ranked second, and a significant increase in Japan, which ranked third. These trends are consistent with previous reports9,21–23 and may reflect the wax and wane of disease with historical asbestos use.24 Accordingly, the burden of disease may be shifting towards countries that used asbestos more recently, such as those in Asia and, to a lesser extent, middle- and low-income countries.

The age-adjusted mortality rate was found to be smaller than the crude mortality rate because mesothelioma deaths were more frequent in developed countries, whose populations are older on average than the reference global population.

The overall mortality rate of less than 10 deaths per million population confirms that the disease is indeed rare. However, the age-specific mortality rate increased steeply with age, to exceed 100 per million in elderly males.

Although the consensus value for the background level of mesothelioma is approximately 1 per million,3,25 we previously speculated that this value could be even lower because an analysis of the ecological relationship between the mortality rate and asbestos use indicated that the graphical intercept was close to zero.26 Consequently, the mortality rates of 1 to 2 per million reported by some middle-income countries may reflect an earlier low but non-zero level of asbestos use.

As previously reported,5,27,28 we found that all forms of mesothelioma predominantly affect elderly individuals aged over 70 years. There was almost no difference in age at death between the genders. Some differences in age at death were observed for different anatomical disease sites: deaths peaked at approximately 70 years for pleural disease, in the middle of the 60–70-year age group for peritoneal disease and at just over 60 years for pericardial disease. For all three anatomical sites, men died 1 to 3 years earlier than women (data not shown). The age at death was lowest in Africa, in middle- and low-income countries and in some specific countries: it was lowest in South Africa. These observations may partially reflect life expectancy in the base populations.

The pleura and unspecified sites were by far the most common disease locations and were reported with similar frequencies. We speculate that, because the gender ratio and the pattern of the age-specific mortality rate were similar for the two, they overlap considerably. The ratio of pleural to peritoneal mesothelioma in this study was 9.2:1. However, a high proportion of unspecified sites was reported by high-incidence countries, such as the United States.24,29 If all unspecified sites are assumed in fact to refer to the pleura, then the pleural-to-peritoneal mesothelioma ratio would be more than doubled, at 18.7:1. Therefore, if survival rates for these two types of mesothelioma are similar, the pleural type would appear to be much more prevalent than the peritoneal, contrary to what previous authors have suggested.25,30 Furthermore, the male-to-female ratio for peritoneal mesothelioma was much lower than for pleural mesothelioma (1.6:1 versus 3.7:1, respectively) and the age at death was also lower (66.0 years versus 70.1 years, respectively). Consequently, even though the etiological role of asbestos is indisputable, peritoneal mesothelioma may involve unique biological mechanisms that have yet to be elucidated.

Geographically, most mesothelioma deaths occurred in the Americas, primarily the United States, and in Europe, particularly in western and northern regions. Generally, deaths occurred in high-income countries. The 10 nations with the highest cumulative number of deaths belong to the industrialized world and included Japan and South Africa. We recently reported that countries with a high cumulative number of mesothelioma deaths also had high cumulative asbestos use.6 South Africa was previously a major producer of asbestos and was the site of the first mesothelioma cluster described.31 Mesothelioma mortality varied considerably between regions. For example, the age-adjusted mortality rate was 6-fold higher in Oceania than in Asia, 16-fold higher in high-income countries than in low-income countries and 5.6-fold higher in the United Kingdom than in Japan.

The male-to-female ratio of 3.6:1 we observed was generally in agreement with ratios reported in previous studies.2,26,32,33 However, the ratio was very high in the United Kingdom, at 5.7:1, and Australia, at 5.4:1, but very low in middle-income countries, at 1.9:1, and in Italy, at 2.4:1. These differences warrant further investigation.

Developing countries are still in the early stages of diagnosing mesothelioma34 and may be prone to misdiagnosis and reporting errors. Along with shorter-life expectancy, these factors may partially account for the higher proportion of disease recorded in younger subjects and the lower peak in age-adjusted mortality rate observed in older populations in middle- and low-income countries (Table 1 and Fig. 4). It is noteworthy that the age and gender characteristics of those who died from mesothelioma in the earlier part of the observation period, who were mostly in high-income countries, were similar to those currently observed in developing countries. We speculate that developing countries, to the extent that they are spared from asbestos-related disease, may be reporting disease rates close to the background level. However, since asbestos use has increased more recently in developing than developed countries, developing countries should prepare for an increase in the number of mesothelioma deaths in the coming decades.

The question of the extent to which our data are representative is important for drawing inferences for global health. In a recent study in the United Kingdom, only two thirds of mesothelioma deaths were identified by analysing the underlying cause of death recorded on death certificates.35 We may also have missed a significant proportion of mesothelioma deaths for a similar reason because the WHO data we used came from countries that code the underlying cause of death using national standards.13 Moreover, no data were available for China, India, Kazakhstan, the Russian Federation or Thailand, which have produced or consumed asbestos at substantial levels for many years.6

In conclusion, malignant mesothelioma remains a rare form of cancer but the disease is on the rise, probably due to the spread of asbestos use over past decades. Our analysis shows that the disease burden is still predominantly borne by the developed world. However, since asbestos use has recently increased in developing countries, a corresponding shift in disease occurrence is anticipated. Our analysis of the global mortality pattern suggests that there are early indications of this shift and lends support to the call by international organizations to eliminate asbestos-related diseases and discontinue the use of asbestos throughout the world.4,36

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Asia–Africa Science Platform Programme of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences and the Project for the Development of a Toolkit for the Elimination of Asbestos-Related Diseases commissioned by the Rotterdam Convention Secretariat.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Anonymous Asbestos, asbestosis, and cancer: the Helsinki criteria for diagnosis and attribution. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1997;23:311–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonald JC, McDonald AD. The epidemiology of mesothelioma in historical context. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:1932–42. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09091932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson BW, Musk AW, Lake RA. Malignant mesothelioma. Lancet. 2005;366:397–408. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elimination of asbestos-related diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2006/WHO_SDE_OEH_06.03_eng.pdf [accessed 30 May 2011].

- 5.Driscoll T, Nelson DI, Steenland K, Leigh J, Concha-Barrientos M, Fingerhut M, et al. The global burden of disease due to occupational carcinogens. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48:419–31. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park EK, Takahashi K, Hoshuyama T, Cheng TJ, Delgermaa V, Le GV, et al. Global magnitude of reported and unreported mesothelioma. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:514–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peto J, Hodgson JT, Matthews FE, Jones JR. Continuing increase in mesothelioma mortality in Britain. Lancet. 1995;345:535–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)90462-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peto J, Decarli A, La Vecchia C, Levi F, Negri E. The European mesothelioma epidemic. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:666–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murayama T, Takahashi K, Natori Y, Kurumatani N. Estimation of future mortality from pleural malignant mesothelioma in Japan based on an age-cohort model. Am J Ind Med. 2006;49:1–7. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montanaro F, Bray F, Gennaro V, Merler E, Tyczynski JE, Parkin DM, et al. ENCR Working Group Pleural mesothelioma incidence in Europe: evidence of some deceleration in the increasing trends. Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:791–803. doi: 10.1023/A:1026300619747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tse LA, Yu IT, Goggins W, Clements M, Wang XR, Au JS, et al. Are current or future mesothelioma epidemics in Hong Kong the tragic legacy of uncontrolled use of asbestos in the past? Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:382–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Health statistics and health information systems: World Health Organization mortality database [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/morttables/en/index.html [accessed 19 May 2011].

- 13.Health statistics and health information systems: about the World Health Organization mortality data [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/mortdata/en/index.html [accessed 19 May 2011].

- 14.International classification of diseases (ICD) [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Available from: http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/ [accessed 19 May 2011].

- 15.International data base (IDB): world population information [Internet]. Washington: United States Census Bureau; 2010. Available from: http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb/worldpopinfo.php [accessed 19 May 2011].

- 16.Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings [Internet]. New York: United Nations Statistics Division; 2011. Available from: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm [accessed 19 May 2011].

- 17.World Bank list of economies [Internet]. Washington: The World Bank; 2011. Available from: http://www.pdwb.de/archiv/weltbank/listgni06.xls [accessed 8 June 2011].

- 18.WHO statistical Information system (WHOSIS) [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Available from: http://www.who.int/whosis/indicators/compendium/2008/1mst/en/index.html [accessed 19 May 2011].

- 19.Bianchi C, Bianchi T. Malignant mesothelioma: global incidence and relationship with asbestos. Ind Health. 2007;45:379–87. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.45.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson BW, Lake RA. Advances in malignant mesothelioma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1591–603. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weill H, Hughes JM, Churg AM. Changing trends in US mesothelioma incidence. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61:438–41. doi: 10.1136/oem.2003.010165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Price B, Ware A. Time trend of mesothelioma incidence in the United States and projection of future cases: an update based on SEER data for 1973 through 2005. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2009;39:576–88. doi: 10.1080/10408440903044928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodgson JT, McElvenny DM, Darnton AJ, Price MJ, Peto J. The expected burden of mesothelioma mortality in Great Britain from 2002 to 2050. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:587–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishikawa K, Takahashi K, Karjalainen A, Wen CP, Furuya S, Hoshuyama T, et al. Recent mortality from pleural mesothelioma, historical patterns of asbestos use, and adoption of bans: a global assessment. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1675–80. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hillerdal G. Mesothelioma: cases associated with non-occupational and low dose exposures. Occup Environ Med. 1999;56:505–13. doi: 10.1136/oem.56.8.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin RT, Takahashi K, Karjalainen A, Hoshuyama T, Wilson D, Kameda T, et al. Ecological association between asbestos-related diseases and historical asbestos consumption: an international analysis. Lancet. 2007;369:844–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60412-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teta MJ, Mink PJ, Lau E, Sceurman BK, Foster ED. US mesothelioma patterns 1973–2002: indicators of change and insights into background rates. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008;17:525–34. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282f0c0a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leigh J, Driscoll T. Malignant mesothelioma in Australia, 1945–2002. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2003;9:206–17. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2003.9.3.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Malignant mesothelioma mortality–United States, 1999–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 200958393–6.http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5815a3.htm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pukkala E, Martinsen JI, Lynge E, Gunnarsdottir HK, Sparén P, Tryggvadottir L, et al. Occupation and cancer - follow-up of 15 million people in five Nordic countries. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:646–790. doi: 10.1080/02841860902913546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wagner JC, Sleggs CA, Marchand P. Diffuse pleural mesothelioma and asbestos exposure in the North Western Cape Province. Br J Ind Med. 1960;17:260–71. doi: 10.1136/oem.17.4.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cook MB, Dawsey SM, Freedman ND, Inskip PD, Wichner SM, Quraishi SM, et al. Sex disparities in cancer incidence by period and age. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1174–82. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Stang N, Belot A, Gilg Soit Ilg A, Rolland P, Astoul P, Bara S, et al. Evolution of pleural cancers and malignant pleural mesothelioma incidence in France between 1980 and 2005. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:232–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takahashi K, Kang S-K. Towards elimination of asbestos-related diseases: a theoretical framework for international cooperation. Safety Health Work. 2010;1:103–6. doi: 10.5491/SHAW.2010.1.2.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harding AH, Darnton AJ. Asbestosis and mesothelioma among British asbestos workers (1971–2005). Am J Ind Med. 2010;53:1070–80. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.ILO adopts new measures on occupational safety and health, the employment relationship, asbestos. Geneva: International Labour Organization; 2006. Available from: https://webdev.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/press-and-media-centre/press-releases/WCMS_070506/lang--en/index.htm [accessed 8 June 2011].